3.1 Defining Theory

When we mention the word theory to our students, we often watch their eyes glaze over as if it is the most boring thing we could talk about. Students sometimes have the misperception that theory has absolutely no relevance in their lives. But did you know that you use and test theories of communication on a daily basis? Whether you know it or not, your theories guide how you communicate. For example, you may have a theory that attractive people are harder to talk to than less attractive people. If you believe this is true, you are probably missing opportunities to get to know entire groups of people.

Our personal theories guide our communication, but there are often problems with them. They generally are not complete or sophisticated enough to help us fully understand the complexities of the communication in which we engage. Therefore, it is essential that we go beyond personal theories to develop and understand ones that guide both our study and performance of communication.

Before we get into the functions that theory performs for us, let’s define what we mean by theory. Kenneth Hoover defined theory as “a set of interrelated propositions that suggest why events occur in the manner that they do.” Foss, Foss, and Griffin defined theory as, “a way of framing an experience or event—an effort to understand and account for something and the way it functions in the world.”

Theories are a way of looking at events, organizing them, and representing them. Take a moment to reflect on the elegant simplicity of these two definitions by Hoover and Foss, Foss and Griffin. Any thoughts or ideas you have about how things work in the world or your life are your personal theories. These theories are essentially your framework for how the world works and guide how you function in the world. You can begin to see how important it is that your theories are solid. As you’ll see, well-developed communication theories help us better understand and explain the communicative behaviors of ourselves and others.

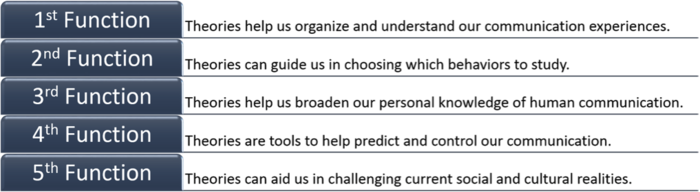

Functions of Communication Theory

While theories in many disciplines can be hard for some to understand, in a field like communication, our theories are important to understand because they directly impact our daily lives. In this respect, they serve several functions in guiding our communication.

In elementary school, you might have believed in cooties. Or you might have believed that if a boy was mean to a girl, he must have liked her, and vice versa. In middle school and high school, finding a date for the homecoming or prom could be one of the most intimidating things to do. Now, in college, the dating world has once again evolved. The ambiguity between what defines a date and a friendly night out can be frustrating for some and exciting for others. Regardless, when situations like these appear, it is easy to seek advice from friends about the situation, ask a parent, or search the web for answers. Each of these resources will likely provide theories about functioning in relationships that you can choose to use or dismiss when clarifying the relationship’s dynamic situation.

The first function theories serve is that they help us organize and understand our communication experiences. We use theories to organize a broad range of experiences into smaller categories by paying attention to “common features” of communication situations (Infante, Rancer & Womack). How many times have you surfed the internet and found articles or quizzes on relationships and what they mean for different genders? Deborah Tannen, author of You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversations, argues that men and women talk in significantly different ways and for significantly different reasons. Of course, these differences cannot be applied to all men and women. But theories on gender communication help us organize and understand the talk of the different genders in a more simplified context so we can understand general patterns of communication behavior. This helps us make appropriate decisions in gendered communication situations.

A second function of theories is that they help us choose what communicative behaviors to study. Theories guide where we choose to look, what we look at, and how we look at communicative phenomena. Remember back to chapter 1 where we defined communication studies. Theories focus our attention on certain aspects of that definition. If you find that Tannen’s theories regarding how men and women talk differ from your own perceptions, or that they’re outdated, you might choose to more closely study the talk or nonverbals of men and women to see if you can rectify the difference in theoretical perspectives. You likely already do this on a personal level. Googling something as simple as “how to act in a relationship” will lead you to hundreds of websites and articles breaking down the dynamics of relationships depending on one’s gender. Likewise, if you want to persuade someone to do something for you, you probably have a theory about what strategies you can use to get them to do what you want. Your theory guides how you approach your persuasive attempts and what you look for to see if you were successful or not.

A third function of theories is that they help us broaden our understanding of human communication. Scholars who study communication share theories with one another online, through books and journal articles, and at conferences. The sharing of theories generates dialogue, which allows us to further refine the theories developed in this field. Tannen’s book allowed the public to rethink the personal theories they had about the communication of men and women. With the opportunity to find countless theories through new books, magazines, the internet, and TV shows, the general public has the opportunity to find theories that will influence how they understand and communicate in the world. But are these theories valid and useful? It’s likely that you discuss your personal theories of communication with others on a regular basis to get their feedback.

A fourth function of theories is that they help us predict and control our communication. When we communicate, we try to predict how our interactions will develop so we can maintain a certain level of control. Imagine being at a party and you want to talk to someone that you find attractive. You will use some sort of theory about how to talk to others to approach this situation in order to make it more successful. As in all situations, the better your theoretical perspectives, the better your chances for success when communicating. While theories do not allow us to predict and control communication with 100% certainty, they do help us function in daily interactions at a more predictable and controlled level. Notice that when you are successful or unsuccessful in your interactions, you use this information to assess and refine your own theoretical perspectives.

A fifth function of theories is that they help us challenge current social and cultural realities by providing new ways of thinking and living. People sometimes make the mistake of assuming that the ways we communicate are innate rather than learned. This is not true. In order to challenge the communicative norms we learn, people use critical theories to ask questions about the status quo of human communication, particularly focusing on how humans use communication to bring advantage and privilege to particular people or groups. For example, Tannen argues that when men listen to women express their troubles, they listen with the purpose of wanting to provide a fix or give advice. Tannen argues that many times, women are looking for not advice or a solution but rather empathy or sympathy from their male conversational partners. With this understanding, it’s possible to begin teaching men new strategies for listening in cross-gendered conversations that serve to build stronger communication ties.

Critical theories challenge our traditional theoretical understandings, providing alternative communicative behaviors for social change.

While theories serve many useful functions, these functions don’t really matter if we do not have well-developed theories that provide a good representation of how our world works. While we all form our personal theories through examining our experiences, how are communication theories developed?

Development of Communication Theories

At this point, you may be wondering where communication theories come from. Because we cannot completely rely on our personal theories for our communication, people like your professors develop communication theories by starting with their own personal interests, observations, and questions about communication (Miller & Nicholson). Those of us who study communication are in a continual process of forming, testing, and reforming theories of communication (Littlejohn & Foss) so that we have a better understanding of our communicative practices. There are three essential steps involved in developing communication theories: (1) ask important questions, (2) look for answers by observing communicative behavior, and (3) form answers and theories as a result of your observations (Littlejohn & Foss).

Asking important questions is the first step in the process of discovering how communication functions in our world. Tannen’s work grew out of her desire to find out answers to questions about why men and women “can’t seem to communicate,” a commonly held theory by many. As a result of her line of questioning, she has spent a career asking questions and finding answers. Likewise, John Gottman has spent his career researching how married couples can be relationally successful. Both their findings and the theories they have developed often contradict common beliefs about how men and women communicate, as well as long-term romantic relationships.

However, simply asking questions is not enough. It is important that we find meaningful answers to our questions in order to continue to improve our communication. In the field of communication, answers to our questions have the potential to help us communicate better with one another as well as provide positive social change. If you’ve ever questioned why something is the way it is, perhaps you’re on your way to discovering the next big theory by finding meaningful answers to your questions.

When we find answers to our questions, we are able to form theories about our communication. Answering our questions helps us develop more sophisticated ways of understanding the communication around us—theories! You may have a theory about how to make friends. You use this theory to guide your behavior, then ask questions to find out if your theory works. The more times you prove that it works, the stronger your theory becomes about making friends. But how do we know if a theory is good or not?

Developing Good Theories

Take a moment to compare Newton’s theory of gravity to communication theories. Simply put, Newton theorized that there is a force that draws objects to the earth. We base our physical behaviors on this theory, regardless of how well we understand its complexities. For example, if you hold a pen above a desk and let go, you know that it will fall and hit the desk every time you drop it. In contrast, communication theories change and develop over time (Infante, Rancer & Womack; Kaplan; Kuhn). For example, you might theorize that smiling at someone should produce a smile back. You speculate that this should happen most of the time, but it probably would not surprise you if it does not happen every time. Contrast this to gravity. If you dropped a pen and it floated, you would likely be very surprised, if not a little bit worried about the state of the world.

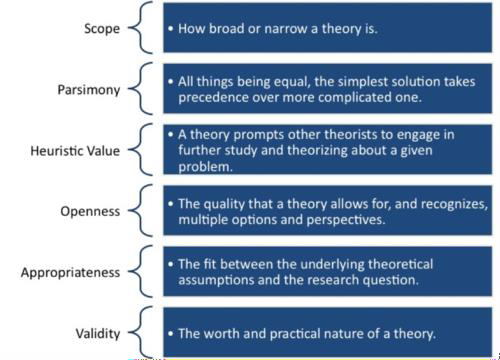

If communication theories are not 100% consistent like theories in the physical sciences, why are they useful? This question has initiated a great deal of debate among those who study communication. While there is no definitive answer to this question, there are a number of criteria we use to evaluate the value of communication theories. According to Littlejohn and Foss, scope, parsimony, heuristic value, openness, appropriateness, and validity are starting places for evaluating whether or not a theory is good.

Scope refers to how broad or narrow a theory is (Infante, Rancer & Womack; Shaw & Costanzo). Theories that cover various domains are considered good theories, but if a theory is too broad, it may not account for specific instances that are important for understanding how we communicate. If it is too narrow, we may not be able to understand communication in general terms. Narrow theories work well if the range of events they cover can be applied to a large number of situations. It is easier to understand some theories when we are given examples or can see them being played out.

Parsimony refers to the idea that, all things being equal, the simplest solution takes precedence over a more complicated one. Thus, a theory is valuable when it is able to explain, in basic terms, complex communicative situations. If the theory cannot be explained in simple terms, it is not demonstrating parsimony.

Heuristic value means that a theory prompts other theorists to engage in further study and theorizing about a given problem. The Greeks used the term heurisko, meaning “I find,” to refer to an idea, which stimulates additional thinking and discovery. This is an important criterion that facilitates intellectual growth, development, and problem-solving. For most communication theories, it would be quite easy to track their development as more people weighed in on the discussion.

Openness is defined as the quality that a theory allows for, and recognizes, multiple options and perspectives. In essence, a good theory acknowledges that it is “tentative, contextual, and qualified” (Littlejohn & Foss, 30) and is open to refinement. The openness of a theory should allow a person to examine its multiple options and perspectives in order to personally determine if the theory holds up or not.

Appropriateness refers to the fit between the underlying theoretical assumptions and the research question. Theories must be consistent with the assumptions, goals, and data of the research in question. Let’s say you want to understand the relationship between playing violent video games and actual violence. One of your assumptions about human nature might be that people are active rather than passive agents, meaning we don’t just copy what we see in the media. Given this, examining this issue from a theoretical perspective that suggests people emulate whatever they see in the media would not be appropriate for explaining a phenomenon.

Validity refers to the worth and practical nature of a theory. The question should be asked, “Is a theory representative of reality?” There are three qualities of validity — value, fit, and generalizability. Is a theory valuable for the culture at large? Does it fit with the relationship between the explanations offered by the theory and the actual data? Finally, is it generalizable to a population beyond the sample size? In our example of the relationship between violent video games and actual violence, let’s say we studied 100 boys and 100 girls, ages 12–15, from a small rural area in California. Could we then generalize or apply our theories to everyone who plays video games?

The above criteria serve as a starting point for generating and evaluating theories. As we move into the next section on specific theoretical paradigms, you will see how some of these criteria work. Let’s now turn to look at ways to more easily conceptualize the broad range of communication theories that exist.

Theoretical Paradigms

One way to simplify the understanding of complex theories is to categorize multiple theories into broader categories, or paradigms. A paradigm is a collection of concepts, values, assumptions, and practices that constitute a way of viewing reality for a community that shares them, especially an intellectual community. According to Thomas Kuhn, intellectual revolutions occur when people abandon previously held paradigms for new ones. For example, when Pythagoras in the 6th century BC argued the earth was a sphere rather than flat, he presented a paradigm shift.

In the field of communication, there are numerous ways to categorize and understand theoretical paradigms. No single way is more valuable than another, nor is any paradigm complete or better in its coverage of communication. Instead, paradigms are a way for us to organize a great number of ideas into categories. For our purposes, we’ve divided communication theories into five paradigms that we call empirical laws, human rules, rhetorical theory, systems theory, and critical paradigms.

A way of looking at events, organizing them, and representing them.

A way for us to organize a great number of ideas into categories.