1.1 Defining Communication

As professors, we hear a lot of people talk about communication both on and off our campuses. We’re often surprised at how few people can actually explain what communication is or what communication departments are about. Even our majors sometimes have a hard time explaining to others what it is they study in college. Throughout this book, we will provide you with the basics for understanding what communication is, what communication scholars and students study, and how you can effectively use the study of communication in your life—whether or not you are a communication major. We accomplish this by taking you on a journey through time. The material in this text is framed chronologically and is largely presented in the context of the events that occurred before the Industrial Revolution (2500 BCE–19th century CE) and after the Industrial Revolution through the present day. In each chapter, we include boxes that provide examples of that chapter’s topic in the context of “then,” “now,” and “you” to help you grasp how the study of communication at colleges and universities impacts life in the real world.

Before we introduce you to verbal and nonverbal communication, history, theories, and research methods and the chronological development of communication specializations, we want to set a foundation in this chapter by explaining communication studies, models of communication, and communication at work.

What Is Communication Studies?

When we tell others that we teach communication, people often ask questions like, Do you teach radio and television? Do you teach public speaking? Do you do news broadcasts? Do you work with computers? Do you study public relations? Is that journalism or mass communication? But the most common question we get is, What is that? It’s interesting that most people will tell us they know what communication is, but they do not have a clear understanding of what it is communication scholars study and teach in our academic discipline. In fact, many professors in other departments on our campus also ask us what it is we study and teach. If you’re a communication major, you’ve probably been asked the same question and, like us, may have had a hard time answering it succinctly. If you memorize the definition below, you will have a quick and simple answer to those who ask you what you study as a communication major.

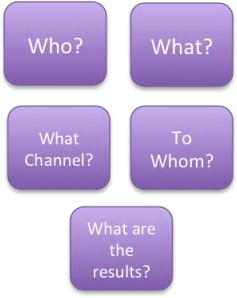

Bruce Smith, Harold Lasswell, and Ralph D. Casey provided a good and simple answer to the question, “What is communication studies?” They state that communication studies is an academic field whose primary focus is “who says what, through what channels (media) of communication, to whom, [and] what will be the results (121).”

Although they gave this explanation almost 70 years ago, to this day it succinctly describes the focus of communication scholars and professionals. As professors and students of communication, we extensively examine the various forms and outcomes of human communication. On its website, the National Communication Association (NCA) states that communication studies “focuses on how people use messages to generate meanings within and across various contexts, cultures, channels, and media. The discipline promotes the effective and ethical practice of human communication…Communication is a diverse discipline which includes inquiry by social scientists, humanists, and critical and cultural studies scholars.” Now, if people ask you what you’re studying in a communication class, you have an answer!

In this course, we will use the Smith, Lasswell, and Casey definition to guide how we discuss the content in this book. Part I sets the foundation by exploring the what and channels (verbal and nonverbal communication) and presenting the whom and results (theories and research methods). Before we get into those chapters, it is important for you to know how we define the actual term communication to give you context for our discussion of it throughout the book.

Defining Communication

As we have already discussed, it’s more difficult than you think. Don’t be discouraged. For decades, communication professionals have had difficulty coming to any consensus about how to define the term communication (Hovland et al.). Even today, there is no single agreed-upon definition of communication. In 1970 and 1984, Frank Dance looked at 126 published definitions of communication within the field and said that the task of trying to develop a single definition of communication that everyone likes is like trying to nail Jell-O to a wall. Thirty years later, defining communication still feels like nailing Jell-O to a wall.

We recognize that there are countless definitions of communication, but we feel it’s important to provide you with our definition so that you understand how we approach each chapter in this book. We are not arguing that this definition of communication is the only one you should consider viable, but you will understand the content of this text better if you understand how we have come to define communication. For the purpose of this text, we define communication as the process of using symbols to exchange meaning.

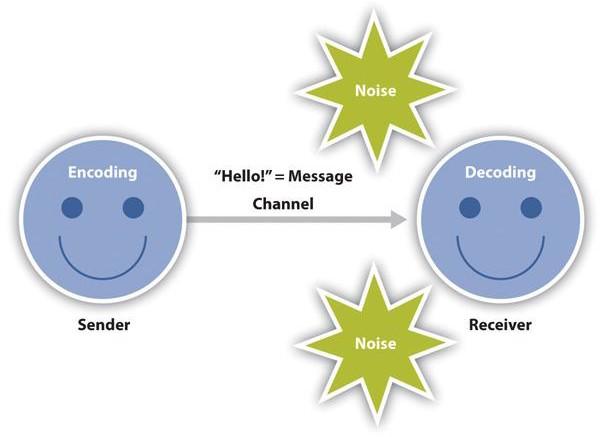

Let’s examine two models of communication to help you further grasp this definition. Shannon and Weaver proposed a Mathematical or Linear Model of Communication that suggests that communication is simply the transmission of a message from one source to another. Watching YouTube videos serves as an example of this. You act as the receiver when you watch videos, receiving messages from the source (the YouTube video). To better understand this, let’s break down each part of this model.

The Linear Model of Communication states that communication moves only in one direction. The sender encodes a message, then uses a certain channel (verbal/nonverbal communication) to send it to a receiver who decodes (interprets) the message. Noise is anything that interferes with or changes the original encoded message.

A sender is someone who encodes and sends a message to a receiver through a particular channel. The sender is the initiator of communication. For example, when you text a friend, ask a teacher a question, or wave to someone, you are the sender of a message.

A receiver is the recipient of a message. Receivers must decode (interpret) messages in ways that are meaningful to them. For example, if you see your friend make eye contact, smile, wave, and say “hello” as you pass, you are receiving a message intended for you. When this happens, you must decode the verbal and nonverbal communication in ways that are meaningful to you.

A message is the particular meaning or content the sender wishes the receiver to understand. The message can be intentional or unintentional, written or spoken, verbal or nonverbal, or any combination of these. For example, as you walk across campus, you may see a friend walking toward you. When you make eye contact, wave, smile, and say “hello,” you are offering a message that is intentional, spoken, verbal, and nonverbal.

A channel is the method a sender uses to send a message to a receiver. The most common channels humans use are verbal and nonverbal forms of communication. Verbal communication relies on language and includes speaking, writing, and sign language. Nonverbal communication includes gestures, facial expressions, paralanguage, and touch. We also use communication channels that are mediated (such as television or the computer), which may utilize both verbal and nonverbal communication. Using the greeting example above, the channels of communication include both verbal and nonverbal communication.

Noise is anything that interferes with the sending or receiving of a message. Noise is external (a jackhammer outside your apartment window or loud music in a nightclub) and internal (physical pain, psychological stress, or nervousness about an upcoming test). External and internal noise make encoding and decoding messages more difficult. Using our ongoing example, if you are on your way to lunch and listening to music on your phone when your friend greets you, you may not hear your friend say “hello,” and you may not wish to chat because you are hungry. In this case, both internal and external noise influenced the communication exchange. Noise is in every communication context, and therefore, no message is received exactly as it is transmitted by a sender because noise distorts it in one way or another.

A major criticism of the Linear Model of Communication is that it suggests communication only occurs in one direction. It also does not show how context or our personal experiences impact communication. Television serves as a good example of the linear model. Have you ever talked back to your television while you were watching it? Maybe you were watching a sporting event or a dramatic show and you talked to the people in the television. Did they respond to you? We’re sure they did not. Television works in one direction. No matter how much you talk to the television, it will not respond to you. Now apply this idea to the communication in your relationships. It seems ridiculous to think that this is how we would communicate with each other on a regular basis. This example shows the limits of the linear model for understanding communication, particularly human-to-human communication.

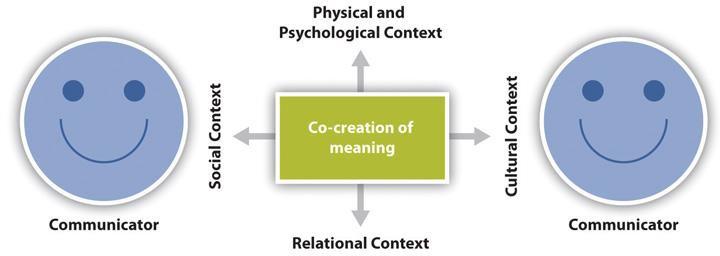

Given the limitations of the Linear Model, Barnlund adapted the model to more fully represent what occurs in most human communication exchanges. The Transactional Model of Communication demonstrates that communication participants act as senders and receivers simultaneously, creating reality through their interactions. Communication is not a simple one-way transmission of a message: the personal filters and experiences of the participants impact each communication exchange. The Transactional Model demonstrates that we are simultaneously senders and receivers and that noise and personal filters always influence the outcomes of every communication exchange.

The Transactional Model of Communication adds to the Linear Model by suggesting that both parties in a communication exchange act as both sender and receiver simultaneously, encoding and decoding messages to and from each other at the same time.

While these models are overly simplistic representations of communication, they illustrate some of the complexities of defining and studying communication. Going back to Smith, Lasswell, and Casey, we may choose to focus on one, all, or a combination of the following: senders of communication, receivers of communication, channels of communication, messages, noise, context, and the outcome of communication. We hope you recognize that studying communication is simultaneously detail-oriented (looking at small parts of human communication) and far-reaching (examining a broad range of communication exchanges).

An academic field whose primary focus is who says what, through what channels of communication, to whom, and what will be the results.

The process of using symbols to exchange meaning.

The transmission of a message from the sender to the receiver.

Someone who initiates communication by encoding and sending a message to a receiver through a particular channel.

Someone who receives a message that they must decode (interpret) in a way that is meaningful for them.

The particular meaning or content the sender wishes the receiver to understand. It can be intentional or unintentional, written or spoken, verbal or nonverbal, or any combination of these.

The method a sender uses to send a message to a receiver such as verbal and nonverbal forms of communication.

Anything external or internal that interferes with the sending or receiving of a message.

Communication participants act as senders and receivers simultaneously, creating reality through their interactions.