8.1 Defining Interpersonal Communication

Before going any further, let us define interpersonal communication. “Inter” means between, among, mutually, or together. The second part of the word, “personal,” refers to a specific individual or particular role that an individual may occupy. Thus, interpersonal communication is communication between individual people. We often engage in interpersonal communication in dyads, which means between two people. It may also occur in small groups such as you and your housemates trying to figure out a system for household chores.

It is important to know that the definition of interpersonal communication is not simply a quantitative one. What this means is that you cannot define it by merely counting the number of people involved. Instead, communication scholars view interpersonal communication qualitatively, meaning that it occurs when people communicate with each other as unique individuals. Thus, interpersonal communication is a process of exchange where there is desire and motivation on the part of those involved to get to know each other as individuals. We will use this definition of interpersonal communication to explore the three primary types of relationships in our lives—friendships, romantic, and family. Given that conflict is a natural part of interpersonal communication, we will also discuss multiple ways of understanding and managing conflict. But before we go into detail about specific interpersonal relationships, let’s examine two important aspects of interpersonal communication: self-disclosure and climate.

Self-Disclosure

Because interpersonal communication is the primary means by which we get to know others as unique individuals, it is important to understand the role of self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is the process of revealing information about yourself to others that is not readily known by them—you have to disclose it. In face-to-face interactions, telling someone “My eyes are brown” would not be self-disclosure because that person can perceive that about you without being told. However, revealing “I am an avid surfer” or “My favorite kind of music is electronic dance” would be examples of self-disclosure because these are pieces of personal information others do not know unless you tell them. Given that our definition of interpersonal communication requires people to build knowledge of one another to get to know them as unique individuals, the necessity for self-disclosure should be obvious.

There are degrees of self-disclosure, ranging from relatively safe (revealing your hobbies or musical preferences) to more personal topics (illuminating fears, dreams for the future, or fantasies). Typically, as relationships deepen and trust is established, self-disclosure increases in both breadth and depth. We tend to disclose facts about ourselves first (I am a biology major), then move toward opinions (I feel the war is wrong), and finally disclose feelings (I’m sad that you said that). An important aspect of self-disclosure is the rule of reciprocity. This rule states that self-disclosure between two people works best in a back-and-forth fashion. When you tell someone something personal, you probably expect them to do the same. When one person reveals more than another, there can be an imbalance in the relationship because the one who self-discloses more may feel vulnerable as a result of sharing more personal information.

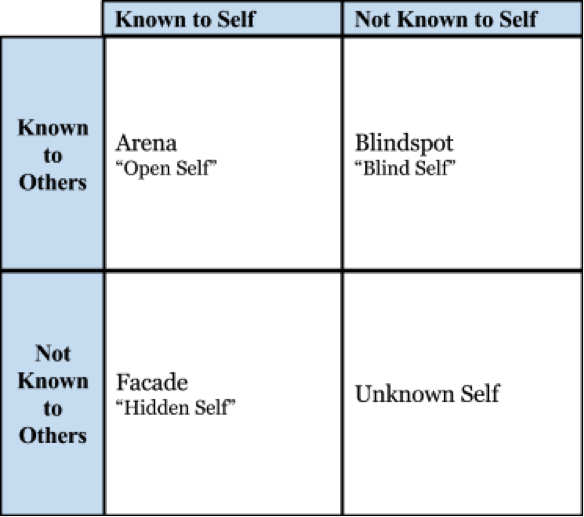

One way to visualize self-disclosure is the Johari window, which comes from combining the first names of the window’s creators, Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham. The window is divided into four quadrants: the arena, the blind spot, the facade, and the unknown.

The arena area contains information that is known to us and to others, such as our height, hair color, occupation, or major. In general, we are comfortable discussing or revealing these topics with most people. Information in the blind spot includes those things that may be apparent to others, yet we are unaware of it in ourselves. The habit of playing with your hair when nervous may be a habit that others have observed but you have not. The third area, the facade, contains information that is hidden from others but is known to you. Previous mistakes or failures, embarrassing moments, or family history are topics we typically hold close and reveal only in the context of safe, long-term relationships. Finally, the unknown area contains information that neither others nor we know about. We cannot know how we will react when a parent dies or just what we will do after graduation until these experiences occur. Knowing about ourselves, especially our blind and unknown areas, enables us to have a healthy, well-rounded self-concept. As we make choices to self-disclose to others, we are engaging in negotiating relational dialectics.

Relational Dialectics

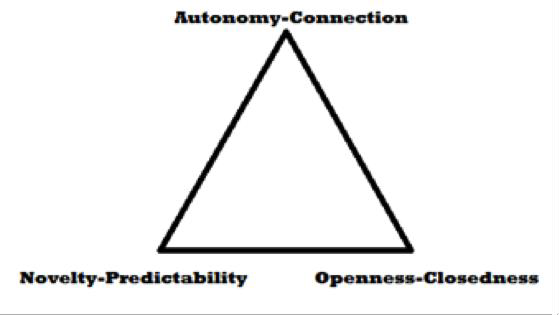

One way we can better understand our personal relationships is by understanding the notion of relational dialectics. Baxter describes three relational dialectics that are constantly at play in interpersonal relationships. Essentially, they are a continuum of needs for each participant in a relationship that must be negotiated by those involved. Let’s take a closer look at the three primary relational dialectics that are at work in all interpersonal relationships.

Autonomy-Connection refers to our need to have a close connection with others as well as our need to have our own space and identity. We may miss our romantic partner when they are away but simultaneously enjoy and cherish that alone time. When you first enter a romantic relationship, you probably want to be around the other person as much as possible. As the relationship grows, you likely begin to desire a need for autonomy, or alone time. In every relationship, each person must balance how much time to spend with the other versus how much time to spend alone.

Novelty-Predictability is the idea that we desire predictability as well as spontaneity in our relationships. In every relationship, we take comfort in a certain level of routine as a way of knowing that we can count on the other person in the relationship. Such predictability provides a sense of comfort and security. However, it requires balance with novelty to avoid boredom. An example of balance might be friends who get together every Saturday for brunch but make a commitment to always try new restaurants each week.

Openness-Closedness refers to the desire to be open and honest with others while at the same time not wanting to reveal everything about ourselves to someone else. One’s desire for privacy does not mean always shutting out others. It is a normal human need. We tend to disclose the most personal information to those with whom we have the closest relationships. However, even these people do not know everything about us. It is natural and acceptable to maintain your own standards for privacy.

How We Handle Relational Dialectics

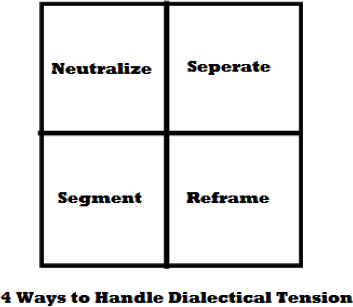

Understanding that these three dialectical tensions are at play in all relationships is a first step in understanding how our relationships work. However, awareness alone is not enough. Couples, friends, or family members have strategies for managing these tensions in an attempt to meet the needs of each person. Baxter identifies four ways we can handle dialectical tensions:

The first option is to neutralize the extremes of the dialectical tensions. Here, individuals compromise, creating a solution where neither person’s need (such as novelty or predictability) is fully satisfied. Individual needs may be different and never fully realized. For example, if one person seeks a great deal of autonomy and the other person in the relationship seeks a great deal of connection, neutralization would not make it possible for either person to have their desires met. Instead, each person might feel like they are not getting quite enough of their particular need met.

The second option is to separate. This is when someone favors one end of the dialectical continuum and ignores the other or alternates between the extremes. For example, a couple in a commuter relationship in which each person works in a different city may decide to live apart during the week (autonomy) and be together on the weekends (connection). In this sense, they are alternating between the extremes by being completely alone during the week yet completely together on the weekends.

When people decide to divide their lives into spheres, they are practicing segmentation. For example, your extended family may be very close and choose to spend religious holidays together. However, members of your extended family might reserve other special days such as birthdays for celebrating with friends. This approach divides needs according to the different segments of your life.

The final option for dealing with these tensions is a reframe. This strategy requires creativity not only in managing the tensions but in understanding how they work in the relationship. For example, the two ends of the dialectic are not viewed as opposing or contradictory at all. Instead, they are understood as supporting the other need as well as the relationship itself. A couple who does not live together, for example, may agree to spend two nights of the week alone or with friends as a sign of their autonomy. The time spent alone or with others gives each person the opportunity to develop themselves and their own interests so that they are better able to share themselves with their partner and enhance their connection.

In general, there is no one right way to understand and manage dialectical tensions, since every relationship is unique. However, to always satisfy one need and ignore the other may be a sign of trouble in the relationship (Baxter). It is important to remember that relational dialectics are a natural part of our relationships and that we have a lot of choice, freedom, and creativity in how we work them out with our relational partners. It is also important to remember that dialectical tensions are negotiated differently in each relationship. The ways we self-disclose and manage dialectical tensions contribute greatly to what we call the communication climate in relationships.