Approaches to Foreign Policy

Lumen Learning and OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain classic schools of thought on U.S. foreign policy

- Describe contemporary schools of thought on U.S. foreign policy

- Delineate the U.S. foreign policy approach with Russia and China

Frameworks and theories help us make sense of the environment of governance in a complex area like foreign policy. A variety of schools of thought exist about how to approach foreign policy, each with different ideas about what “should” be done. These approaches also vary in terms of what they assume about human nature, how many other countries ought to be involved in U.S. foreign policy, and what the tenor of foreign policymaking ought to be. They help us situate the current U.S. approach to many foreign policy challenges around the world.

CLASSIC APPROACHES

A variety of traditional concepts of foreign policy remain helpful today as we consider the proper role of the United States in, and its approach to, foreign affairs. These include isolationism, the idealism versus realism debate, liberal internationalism, hard versus soft power, and the grand strategy of U.S. foreign policy.

From the end of the Revolutionary War in the late eighteenth century until the early twentieth century, isolationism—whereby a country stays out of foreign entanglements and keeps to itself—was a popular stance in U.S. foreign policy. Among the founders, Thomas Jefferson especially was an advocate of isolationism or non-involvement. He thought that by keeping to itself, the United States stood a better chance of becoming a truly free nation. This fact is full of irony, because Jefferson later served as ambassador to France and president of the United States, both roles that required at least some attention to foreign policy. Still, Jefferson’s ideas had broad support. After all, Europe was where volatile changes were occurring. The new nation was tired of war, and there was no reason for it to be entangled militarily with anyone. Indeed, in his farewell address, President George Washington famously warned against the creation of “entangling alliances.”[1]

Despite this legacy, the United States was pulled squarely into world affairs by President Woodrow Wilson with its entry into World War I. But between the Armistice in 1918 that ended that war and U.S. entry into World War II in 1941, isolationist sentiment returned, based on the idea that Europe should learn to govern its own affairs. Then, after World War II, the United States engaged the world stage as one of two superpowers and the military leader of Europe and the Pacific. Isolationism never completely went away, but now it operated in the background. Again, Europe seemed to be the center of the problem, while political life in the United States seemed calmer somehow.

The end of the Cold War opened up old wounds as a variety of smaller European countries sought independence and old ethnic conflicts reappeared. Some in the United States felt the country should again be isolationist as the world settled into a new political arrangement, including a vocal senator, Jesse Helms (R-NC), who was against the United States continuing to be the military “policeman” of the world. Helms was famous for opposing nearly all treaties brought to the Senate during his tenure. Congressman Ron Paul (R-TX) and his son Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) were both isolationist candidates for the presidency (in 2008 and 2016, respectively); both thought the United States should retreat from foreign entanglements, spend far less on military and foreign policy, and focus more on domestic issues.

At the other end of the spectrum is liberal internationalism. Liberal internationalism advocates a foreign policy approach in which the United States becomes proactively engaged in world affairs. Its adherents assume that liberal democracies must take the lead in creating a peaceful world by cooperating as a community of nations and creating effective world structures such as the United Nations. To fully understand liberal internationalism, it is helpful to understand the idealist versus realist debate in international relations. Idealists assume the best in others and see it as possible for countries to run the world together, with open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, free trade, and no militaries. Everyone will take care of each other. There is an element of idealism in liberal internationalism, because the United States assumes other countries will also put their best foot forward. A classic example of a liberal internationalist is President Woodrow Wilson, who sought a League of Nations to voluntarily save the world after World War I.

Realists, working from the tradition of thought extending back to Thucydides and Sun Tsu known as Realism, assume that others will act in their own self-interest and hence cannot necessarily be trusted. They want a healthy military and contracts between countries in case others want to wiggle out of their commitments. Realism also has a place in liberal internationalism, because the United States approaches foreign relationships with open eyes and an emphasis on self-preservation.

Both the Liberal and Realist traditions typically assume that the international system is Anarchic. This anarchy is a condition where there is no overarching authority present in the international system that is capable of enforcing agreements. While the interpretation of this anarchy varies wildly between Realists, who view anarchy as a state of paranoia and distrust, and Liberals, who view anarchy as a system free of impediments to building agreements and international institutions, the international system does hold closely to being an anarchic system. Ultimately, as Alexander Wendt stated, anarchy is what states make of it.

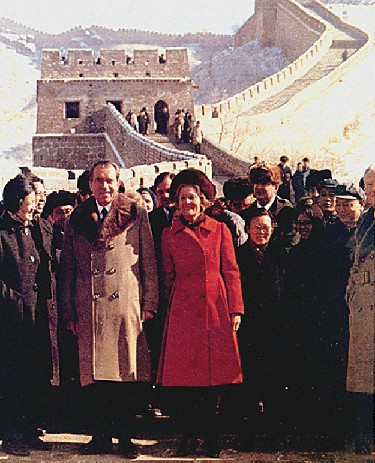

Soft power, or diplomacy, with which the United States often begins a foreign policy relationship or entanglement, is in line with liberal internationalism and idealism, while hard power, which allows the potential for military force, is the stuff of realism. For example, at first the United States was rather isolationist in its approach to China, assuming it was a developing country of little impact that could safely be ignored. Then President Nixon opened up China as an area for U.S. investment, and an era of open diplomatic relations began in the early 1970s. As China modernized and began to dominate the trade relationship with the United States, many came to see it through a realist lens and to consider whether China’s behavior really warranted its beneficial most-favored-nation trading status.

The final classic idea of foreign policy is the so-called grand strategy—employing all available diplomatic, economic, and military resources to advance the national interest. The grand strategy invokes the possibility of hard power, because it relies on developing clear strategic directions for U.S. foreign policy and the methods to achieve those goals, often with military capability attached. The U.S. foreign policy plan in Europe and Asia after World War II reflects a grand strategy approach. In order to stabilize the world, the United States built military bases in Italy, Germany, Spain, England, Belgium, Japan, Guam, and Korea. It still operates nearly all these, though often under a multinational arrangement such as NATO. These bases help preserve stability on the one hand, and U.S. influence on the other.

MORE RECENT SCHOOLS OF THOUGHTS

Two particular events in foreign policy caused many to change their views about the proper approach to U.S. involvement in world affairs. First, the debacle of U.S. involvement in the civil war in Vietnam in the years leading up to 1973 caused many to rethink the country’s traditional containment approach to the Cold War. Containment was the U.S. foreign policy goal of limiting the spread of communism. In Vietnam the United States supported one governing faction within the country (democratic South Vietnam), whereas the Soviet Union supported the opposing governing faction (communist North Vietnam). The U.S. military approach of battlefield engagement did not translate well to the jungles of Vietnam, where “guerilla warfare” predominated.

Skeptics became particularly pessimistic about liberal internationalism given how poorly the conflict in Vietnam had played out. U.S. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam in 1973, and Saigon, its capital, fell to North Vietnam and the communists eighteen months later. Many of those pessimists then became neoconservatives on foreign policy.

Neoconservatives believe that rather than exercising restraint and always using international organizations as the path to international outcomes, the United States should aggressively use its might to promote its values and ideals around the world. The aggressive use (or threat) of hard power is the core value of neoconservatism.

Acting unilaterally is acceptable in this view, as is adopting a preemptive strategy in which the United States intervenes militarily before the enemy can make its move. Preemption is a new idea; the United States has tended to be retaliatory in its use of military force, as in the case of Pearl Harbor at the start of World War II. Examples of neoconservativism in action are the 1980s U.S. campaigns in Central American countries to turn back communism under President Ronald Reagan, the Iraq War of 2003 led by President George W. Bush and his vice president Dick Cheney, and the use of drones as counterterrorism weapons during the Obama administration.

Neo-isolationism, like earlier isolationism, advocates keeping free of foreign entanglements. Yet no advanced industrial democracy completely separates itself from the rest of the world. Foreign markets beckon, tourism helps spur economic development at home and abroad, and global environmental challenges require cross-national conversation. In the twenty-first century, neo-isolationism means distancing the United States from the United Nations and other international organizations that get in the way. The strategy of selective engagement—retaining a strong military presence and remaining engaged across the world through alliances and formal installations—is used to protect the national security interests of the United States. However, this strategy also seeks to avoid being the world’s police officer.

The second factor that changed minds about twenty-first century foreign policy is the rise of elusive new enemies who defy traditional designations. Rather than countries, these enemies are terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda and ISIS (or ISIL) that spread across national boundaries. A hybrid approach to U.S. foreign policy that uses multiple schools of thought as circumstances warrant may thus be the wave of the future. President Obama often took a hybrid approach. In some respects, he was a liberal internationalist seeking to put together broad coalitions to carry out world business. At the same time, his sending teams of troops and drones to take out terrorist targets in other legitimate nation-states without those states’ approval fits with a neoconservative approach. Finally, his desire to not be the “world’s police officer” led him to follow a practice of selective engagement.

The current international system is seeing the emergence of competition over which set of international institutions each state will choose to join. While the decades since the Cold War have been dominated by the post-war agreements of the United Nations and the set of Bretton Woods institutions that have evolved into what can best be described as the World Trade System, the last 10 years have seen a new set of institutions emerge based on Chinese influence in the international system. These new institutions, collectively known as the Belt and Road Initiative provide a different set of institutional choices to the nations around the world. The coming decades will see competition between these two systems for Hegemonic Dominance.

LINK TO LEARNING

Several interest groups debate what should happen in U.S. foreign policy, many of which are included in this list compiled by project Vote Smart.

U.S. FOREIGN POLICY IN THE COLD WAR AND WITH CHINA

The foreign policy environment from the end of World War II until the end of the Cold War in 1990 was dominated by a duel of superpowers between the United States and its Western allies on the one hand and the Soviet Union and the communist bloc of countries in the East on the other. Both superpowers developed thousands of weapons of mass destruction and readied for a potential world war to be fought with nuclear weapons. That period was certainly challenging and ominous at times, but it was simpler than the present era. Nations knew what team they were on, and there was generally an incentive to not go to war because it would lead to the unthinkable—the end of the Earth as we know it, or mutually assured destruction. The result of this logic, essentially a standoff between the two powers, is sometimes referred to as nuclear deterrence.

When the Soviet Union imploded and the Cold War ended, it was in many ways a victory for the West and for democracy. However, once the bilateral nature of the Cold War was gone, dozens of countries sought independence and old ethnic conflicts emerged in several regions of the world, including Eastern Europe. This new era holds great promise, but it is in many ways more complex than the Cold War. The rise of cross-national terrorist organizations further complicates the equation because the enemy hides within the borders of potentially dozens of countries around the globe. In summary, the United States pursues a variety of topics and goals in different areas of the world in the twenty-first century.

The Soviet Union dissolved into many component parts after the Cold War, including Russia, various former Soviet republics like Georgia and Ukraine, and smaller nation-states in Eastern Europe, such as the Czech Republic. The general approach of the United States has been to encourage the adoption of democracy and economic reforms in these former Eastern bloc countries. Many of them now align with the EU and even with the West’s cross-national military organization, NATO. With freedoms can come conflict, and there has been much of that in these fledgling countries as opposition coalitions debate how the future course should be charted, and by whom. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia is again trying to strengthen its power on the country’s western border, testing expansionism while invoking Russian nationalism. The United States is adopting a defensive position and trying to prevent the spread of Russian influence. The EU and NATO factor in here from the standpoint of an internationalist approach. U.S.-Russia relations have been frosty since Putin ascended, save for President Trump’s efforts to befriend him. President Biden has taken a more emphatic stand with Russia on issues of wrongdoing and especially questions regarding Russian influence in the 2016 and 2020 elections.

In many ways the more visible future threat to the United States is China, the potential rival superpower of the future, and founder of the Belt and Road Initiative. A communist state that has also encouraged much economic development, China has been growing and modernizing for more than thirty years. Its nearly 1.4 billion citizens are stepping onto the world economic stage with other advanced industrial nations. In addition to fueling an explosion of industrial domestic development, public and private Chinese investors have spread their resources to every continent and most countries of the world. Indeed, Chinese investors lend money to the United States government on a regular basis, as U.S. domestic borrowing capacity is pushed to the limit in most years.

Many in the United States are worried by the lack of freedom and human rights in China. During the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing on June 4, 1989, thousands of pro-democracy protestors were arrested and many were killed as Chinese authorities fired into the crowd and tanks crushed people who attempted to wall them out. Over one thousand more dissidents were arrested in the following weeks as the Chinese government investigated the planning of the protests in the square. The United States instituted minor sanctions for a time, but President George H. W. Bush chose not to remove the most-favored-nation trading status of this long-time economic partner. Most in the U.S. government, including leaders in both political parties, wish to engage China as an economic partner at the same time that they keep a watchful eye on its increasing influence around the world, especially in developing countries. President Trump, on the other hand, was assertive in Asia, imposing a series of tariffs designed particularly to hit goods imported from China. The relationship with China therefore became quite strained under President Trump, and President Biden has continued to raise tough questions about and take tough stances on China. This souring relationship has negatively impacted U.S. universities where several Confucius Institutes have been shut down.

Elsewhere in Asia, the United States has good relationships with most other countries, especially South Korea and Japan, which have both followed paths the United States favored after World War II. Both countries embraced democracy, market-oriented economies, and the hosting of U.S. military bases to stabilize the region. North Korea, however, is another matter. A closed, communist, totalitarian regime, North Korea has been testing nuclear bombs in recent decades, to the concern of the rest of the world. Here, again, President Trump was assertive, challenging the North Koreans to come to the bargaining table. It is an open question how much change this assertiveness will achieve, but it is significant that a dialogue has actually begun. Like China many decades earlier, India is a developing country with a large population that is expanding and modernizing. Unlike China, India has embraced democracy, especially at the local level.

LINK TO LEARNING

You can plot U.S. government attention to different types of policy matters (including international affairs and foreign aid and its several dozen more focused subtopics) by using the online trend analysis tool at the Comparative Agendas Project.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 17.4 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- "George Washington’s Farewell Address." 1796. New Haven, CT: School Avalon Project, Yale Law Library. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/washing.asp (May 12, 2016). ↵

laws that require government documents and proceedings to be made public

the right of a journalist to keep a source confidential

spoken information about a person or organization that is not true and harms the reputation of the person or organization

the right of a journalist to keep a source confidential

printed information about a person or organization that is not true and harms the reputation of the person or organization

printed information about a person or organization that is not true and harms the reputation of the person or organization