Competitive Federalism Today

Lumen Learning and OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the dynamic of competitive federalism

- Analyze some issues over which the states and federal government have contended

Certain functions clearly belong to the federal government, the state governments, and local governments. National security is a federal matter, the issuance of licenses is a state matter, and garbage collection is a local matter. One aspect of competitive federalism today is that some policy issues, such as immigration and the marital rights of LGBTQ people, have been redefined as the roles that states and the federal government play in them have changed. Another aspect of competitive federalism is that interest groups seeking to change the status quo can take a policy issue up to the federal government or down to the states if they feel it is to their advantage. Interest groups have used this strategy to promote their views on such issues as abortion, gun control, and the legal drinking age.

CONTENDING ISSUES

Immigration and marriage equality have not been the subject of much contention between states and the federal government until recent decades. Before that, it was understood that the federal government handled immigration and states determined the legality of marriage, whether between people of different races or the same sex. This understanding of exclusive responsibilities has changed; today both levels of government play roles in these two policy areas.

Immigration federalism describes the gradual movement of states into the immigration policy domain.[1] Since the late 1990s, states have asserted a right to make immigration policy on the grounds that they are enforcing, not supplanting, the nation’s immigration laws, and they are exercising their jurisdictional authority by restricting undocumented immigrants’ access to education, health care, and welfare benefits, areas that fall under the states’ responsibilities. In 2005, twenty-five states had enacted a total of thirty-nine laws related to immigration; by 2014, forty-three states and Washington, DC, had passed a total of 288 immigration-related laws and resolutions.[2] In 2020, thirty-two different states enacted a total of 206 new measures, including many related to COVID-19.[3]

Arizona has been one of the states at the forefront of immigration federalism. In 2010, it passed Senate Bill 1070, which sought to make it so difficult for undocumented immigrants to live in the state that they would return to their native country, a strategy referred to as “attrition by enforcement.”[4] The federal government filed suit to block the Arizona law, contending that it conflicted with federal immigration laws. Arizona’s law has also divided society, because some groups have supported its tough stance on immigrants, while other groups have opposed it for humanitarian and human-rights reasons. According to a poll of Latino voters in the state by Arizona State University researchers, 81 percent opposed this bill.[5]

In 2012, in Arizona v. United States, the Supreme Court affirmed federal supremacy on immigration.[6] The court struck down three of the four central provisions of the Arizona law—namely, those allowing police officers to arrest an undocumented immigrant without a warrant if they had probable cause to think the immigrant had committed a crime that could lead to deportation, making it a crime to seek a job without proper immigration documentation, and making it a crime to be in Arizona without valid immigration papers. The court upheld the “show me your papers” provision, which authorizes police officers to check the immigration status of anyone they stop or arrest who they suspect is an undocumented immigrant.[7] However, in letting this provision stand, the court warned Arizona and other states with similar laws that they could face civil rights lawsuits if police officers applied it based on racial profiling.[8] All in all, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion embraced an expansive view of the U.S. government’s authority to regulate immigration, describing it as broad and undoubted. That authority derived from the legislative power of Congress to “establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization,” enumerated in the Constitution. During the COVID-19 pandemic, California moved in the opposite direction. The California Immigrant Resilience Fund led to the provision of $75 million for undocumented Californians not eligible for other COVID-19 programs.

LINK TO LEARNING

Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070 has been the subject of heated debate. Read the views of proponents and opponents of the law.

LGBTQ marital rights have also significantly changed in recent years. By passing the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, the federal government stepped into this policy issue. Not only did DOMA allow states to choose whether to recognize same-sex marriages, it also defined marriage as a union between a man and a woman, which meant that same-sex couples were denied various federal provisions and benefits—such as the right to file joint tax returns and receive Social Security survivor benefits. In 1997, more than half the states in the union had passed some form of legislation banning same-sex marriage. By 2006, two years after Massachusetts became the first state to recognize marriage equality, twenty-seven states had passed constitutional bans on same-sex marriage. In United States v. Windsor, the Supreme Court changed the dynamic established by DOMA by ruling that the federal government had no authority to define marriage. The Court held that states possess the “historic and essential authority to define the marital relation” and that the federal government’s involvement in this area “departs from this history and tradition of reliance on state law to define marriage.”[9]

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Edith Windsor: Icon of the Marriage Equality Movement

Edith Windsor, the plaintiff in the landmark Supreme Court case United States v. Windsor, has become an icon of the marriage equality movement for her successful effort to force repeal the DOMA provision that denied married same-sex couples a host of federal provisions and protections. In 2007, after having lived together since the late 1960s, Windsor and her partner Thea Spyer were married in Canada, where same-sex marriage was legal. After Spyer died in 2009, Windsor received a $363,053 federal tax bill on the estate Spyer had left her. Because her marriage was not valid under federal law, her request for the estate-tax exemption that applies to surviving spouses was denied. With the counsel of her lawyer, Roberta Kaplan, Windsor sued the federal government and won.

Because of the Windsor decision, federal laws could no longer discriminate against same-sex married couples. What is more, marriage equality became a reality in a growing number of states as federal court after federal court overturned state constitutional bans on same-sex marriage. The Windsor case gave federal judges the moment of clarity from the U.S. Supreme Court that they needed. James Esseks, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender & AIDS Project, summarizes the significance of the case as follows: “Part of what’s gotten us to this exciting moment in American culture is not just Edie’s lawsuit but the story of her life. The love at the core of that story, as well as the injustice at its end, is part of what has moved America on this issue so profoundly.”[10] In the final analysis, same-sex marriage is a protected constitutional right as decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, which took up the issue again when it heard Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

What role do you feel the story of Edith Windsor played in reframing the debate over same-sex marriage? How do you think it changed the federal government’s view of its role in legislation regarding same-sex marriage relative to the role of the states?

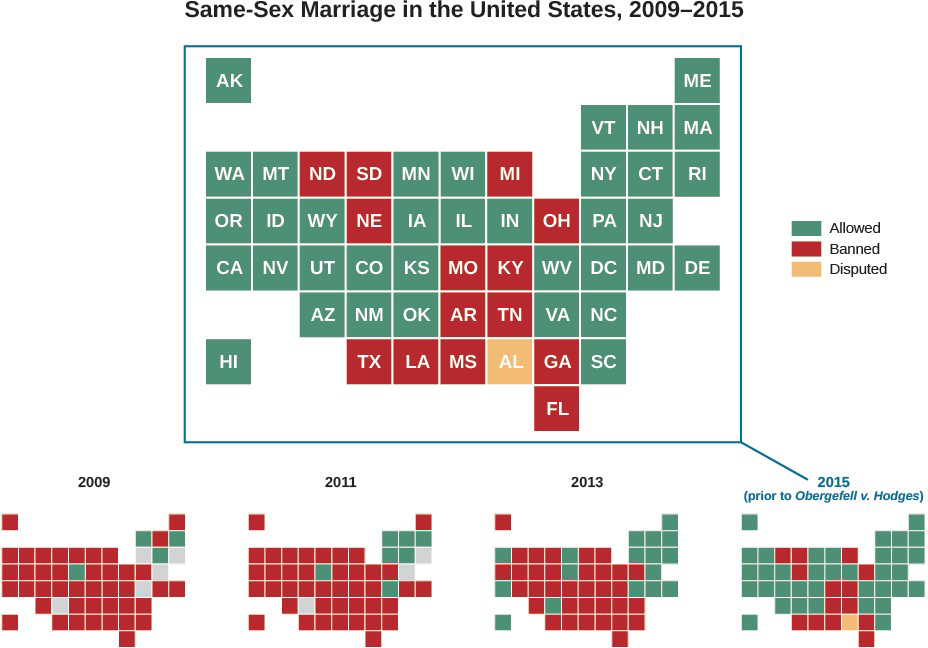

Following the Windsor decision, the number of states that recognized same-sex marriages increased rapidly, as illustrated in Figure 3. In 2015, marriage equality was recognized in thirty-six states plus Washington, DC, up from seventeen in 2013. The diffusion of marriage equality across states was driven in large part by federal district and appeals courts, which have used the rationale underpinning the Windsor case (i.e., laws cannot discriminate between same-sex and different-sex couples based on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment) to invalidate state bans on same-sex marriage. The 2014 court decision not to hear a collection of cases from four different states essentially affirmed same-sex marriage in thirty states. And in 2015 the Supreme Court gave same-sex marriage a constitutional basis of right nationwide in Obergefell v. Hodges. In sum, as the immigration and marriage equality examples illustrate, constitutional disputes have arisen as states and the federal government have sought to reposition themselves on certain policy issues, disputes that the federal courts have had to sort out.

STRATEGIZING ABOUT NEW ISSUES

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) was established in 1980 by a woman whose thirteen-year-old daughter had been killed by a drunk driver. The organization lobbied state legislators to raise the drinking age and impose tougher penalties, but without success. States with lower drinking ages had an economic interest in maintaining them because they lured youths from neighboring states with restricted consumption laws. So MADD decided to redirect its lobbying efforts at Congress, hoping to find sympathetic representatives willing to take action. In 1984, the federal government passed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act (NMDAA), a crosscutting mandate that gradually reduced federal highway grant money to any state that failed to increase the legal age for alcohol purchase and possession to twenty-one. After losing a legal battle against the NMDAA, all states were in compliance by 1988.[11]

By creating two institutional access points—the federal and state governments—the U.S. federal system enables interest groups such as MADD to strategize about how best to achieve their policy objectives. The term venue shopping refers to a strategy in which interest groups select the level and branch of government (legislature, judiciary, or executive) they calculate will be most advantageous for them.[12] If one institutional venue proves unreceptive to an advocacy group’s policy goal, as state legislators were to MADD, the group will attempt to steer its issue to a more responsive venue.

The strategy anti-abortion advocates have used in recent years is another example of venue shopping. In their attempts to limit abortion rights in the wake of the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision making abortion legal nationwide, anti-abortion advocates initially targeted Congress in hopes of obtaining restrictive legislation.[13] Lack of progress at the national level prompted them to shift their focus to state legislators, where their advocacy efforts have been more successful. By 2015, for example, thirty-eight states required some form of parental involvement in a minor’s decision to have an abortion, forty-six states allowed individual health-care providers to refuse to participate in abortions, and thirty-two states prohibited the use of public funds to carry out an abortion except when the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest. While 31 percent of U.S. women of childbearing age resided in one of the thirteen states that had passed restrictive abortion laws in 2000, by 2013, about 56 percent of such women resided in one of the twenty-seven states where abortion is restricted.[14]

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 3.4 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Carol M. Swain and Virginia M. Yetter. (2014). "Federalism and the Politics of Immigration Reform." In The Politics of Major Policy Reform in Postwar America, eds. Jeffery A. Jenkins and Sidney M. Milkis. New York: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- National Conference of State Legislatures. "State Laws Related to Immigration and Immigrants." http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/state-laws-related-to-immigration-and-immigrants.aspx (June 23, 2015). ↵

- Ann Morse, "Report on State Immigration Laws - 2020," National Conference of State Legislatures, 8 March 2021, https://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/report-on-state-immigration-laws-2020.aspx. ↵

- Michele Waslin. 2012. "Discrediting ‘Self Deportation’ as Immigration Policy," February 6. http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/special-reports/discrediting-%E2%80%9Cself-deportation%E2%80%9D-immigration-policy ↵

- Daniel González. 2010. "SB 1070 Backlash Spurs Hispanics to Join Democrats," June 8. http://archive.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/news/articles/2010/06/08/20100608arizona-immigration-law-backlash.html ↵

- Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. __ (2012). ↵

- Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. __ (2012). ↵

- Julia Preston, "Arizona Ruling Only a Narrow Opening for Other States," New York Times, 25 June 2012. ↵

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. __ (2013). ↵

- James Esseks. 2014. "Op-ed: In the Wake of Windsor," June 26. http://www.advocate.com/commentary/2014/06/26/op-ed-wake-windsor (June 24, 2015). ↵

- South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987). ↵

- Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↵

- Elizabeth Nash et al. 2013. "Laws Affecting Reproductive Health and Rights: 2013 State Policy Review." http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/updates/2013/statetrends42013.html (June 24, 2015). ↵

the gradual movement of states into the immigration policy domain traditionally handled by the federal government

a strategy in which interest groups select the level and branch of government they calculate will be most receptive to their policy goals