Chapter 1.2 Primary Sources

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify different types of primary sources

- Analyze primary sources in a historical context

- Interpret primary sources effectively

Historians develop interpretations of the past based on source material, and we do the same in this book. From ancient hieroglyphs to works of art to blog posts, from histories and biographies written by later scholars to Google Maps, sources help us build our interpretations of the human story.

Learning to Evaluate Documents and Images

There are two main kinds of historical sources, primary and secondary. A primary source is a gateway to the past because it is an object or document that comes directly from the time period to which it refers. Primary sources might be government documents, menus from restaurants, diaries, letters, musical instruments, photographs, portraits drawn from life, songs, and so on. If a historian is looking at Ancient Egypt, a statue of a pharaoh is a primary source for that time period, as are hieroglyphs that tell of the pharaoh’s reign. Primary sources, when we have them, are considered more valuable than other sources because they are as close in time as we can get to the events being studied. Think, for example, of a court trial: The ideal is to have the trial quickly so that witness testimony is fresher and therefore more reliable. With the passage of time, people can forget, they might subconsciously add or take away parts of a memory, and they may be influenced to interpret events differently.

A secondary source is one written or created after the fact. A twentieth-century biography of an Egyptian pharaoh is a secondary source, as is a map drawn in the 1960s to identify the battle sites of World War II (1939–1945) and a museum curator’s blog post about the artistic achievements of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). These types of scholarly sources are critical for the evolution of historical knowledge and are often the place students begin to form an understanding of past events. Secondary sources are useful for setting context and placing a topic in relation to others of the same era. They also provide access to scholarly research based on primary sources for students whose access might be limited by language or geography. Good research requires both types of sources and some attention to historiography, which is the study of how other historians have already interpreted and written about the past.

All primary sources are not equal. History technically begins with the advent of writing, when humans began to deliberately make records and, after that, to develop the idea that preserving the past was a worthwhile endeavor. This is not to say that there isn’t anything valuable to be found in the oral histories of preliterate societies, or in prehistoric cave paintings and archaeological artifacts. For historians, however, the written word is more accurate evidence for building narratives of the past. For example, imagine a modern magazine with a rock or pop star on the front, dressed for performance in a vibrant or provocative style. If that were the only piece of evidence that existed five hundred years from now, how would historians interpret our era? Without context, interpretation of the past is quite difficult. Studying artifacts is certainly worthwhile, but text offers us greater clarity. Even if the cover of the magazine bore only a caption, like “Pop star rising to the top of the charts,” future historians would have significantly more information than from the photo alone. However, even textual sources must be met with a critical eye. “Fake news” is not new, but the speed at which it travels today is unprecedented. We must investigate the full context of any source and look for corroboration.

It takes time to develop the skills necessary to interpret primary sources. As an example, consider the act of reading a poem. You can read the surface of a poem, the literal meaning of the words presented. But that seldom reflects the true meaning the poet meant to convey. You must also look for nuances, hidden meanings, or repeated metaphors. We approach a primary source in a similar way.

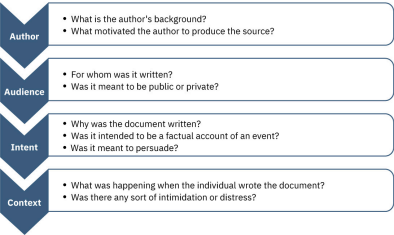

There are four key areas to consider when interpreting sources: the author, the audience, the intent, and the context. Here are some key questions to ask yourself when exploring a new source:

- What kind of source is it? Government documents have a different purpose than personal diaries. A former president commenting on a political issue has a different view from a comedian doing the same.

- Who authored the source and why? Is the author responsible for simply recording the information, or was the author involved in the event? Is the author reliable, or does the author have an agenda?

- What is the historical context? How does the source relate to the events covered in the chapter?

None of the answers disqualify a source from adding value, but precisely what that source brings to the overall picture depends heavily on those answers.

![]() LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

This is a presentation on working with primary sources (opens in new tab) produced by the Smithsonian. Pay particular attention to section 2, “Documents.” Read through it and take note of the kinds of questions to ask as you critically assess primary sources. You may want to write them down or have them on hand for reference as you work your way through this text.

In a world where many sources are available in digital format, searching online, as many students do, is a convenient way of doing research. But the internet has just as much misinformation as it has legitimate sources. Historians evaluate the strength of both primary and secondary sources, especially online. How do we decide what a good source is? Some clues are more obvious than others. For example, it is unlikely any truly scholarly material will be found on the first page of a Google search, unless the search terms include key phrases or use targeted search engines such as Google Scholar. Online encyclopedias may be a good place to start your research, but they should be only a springboard to more refined study.

Your work is only as strong as the sources you use. Whether you are writing a paper, a discussion post online, or even a creative writing piece, the better your sources, the more persuasive your writing will be. Sites like Wikipedia and Encyclopedia.com offer a quick view of content, but they will not give enough depth to allow for the critical thinking necessary to produce quality work. However, they are useful for introducing a topic with which you might not be familiar. And if you start with encyclopedic sources, you can often find pathways to better sources. They might spark new lines of inquiry, for instance, or have bibliographic information that can lead you to higher-quality material.

Always make sure you can tell who is producing the website. Is it a scholar, a museum, or a research organization? If so, there is a good chance the material is sound. Is the information cited? In other words, does the source tell you where it got the information? Are those sources in turn objective and reliable? Can you corroborate the site’s information? This means doing some fact checking. You should see whether other sources present similar data and whether your source fits into the narrative developed by other scholars. Does your school library list the site as a resource? Finally, if you are not sure, ask. Librarians work in online spaces too, and you can generally reach out to these experts with any questions.

As you explore history via this text, you will be asked many times to read and interpret primary sources. These will normally be set off as feature boxes, as noted earlier. Let’s work through a few examples. The goal is to become more familiar with the types of questions you should ask of sources, as well as the variety of sources you will work with throughout the text.

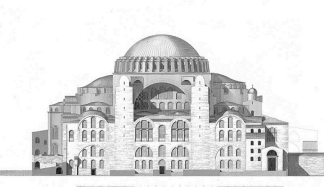

First, an image exercise. The following images are exterior and interior views of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, a wonder of late antiquity whose name means “Holy Wisdom” in Greek. Buildings and other material objects change as they are affected by historical events. Images of them can tell us much about those events and the people who enter or interact with them.

The first set of images (Figure 1.5 and Figure 1.6) provide a likeness of the famous church at the time it was built, during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (483–565 CE). The domed structure was unique for its engineering and stunning in its effect. Decorated with Greek iconography, the visual images and symbols used in a work of art, the basilica stood as an emblem of Justinian’s power, the awesome nature of the Christian God, and the surviving wealth and stability of the East. Churches at the time were meant to inspire awe; because most people could not read, stories of religious figures and events were told through highly decorative and symbolic images, and obedience and a desire to join a religious community could be motivated by the buildings’ grandeur. As you study the renderings, reflect on the following questions: What are the key features of the building? What does it make you think about? What does it tell you about the period in which it was built? What would you think about it if you were a poor sixth-century farmer, an urban merchant of some wealth, or a foreign leader?

In 1453, nearly a thousand years after the reign of Justinian, the city of Constantinople (now called Istanbul in present-day Turkey) was conquered by Muslim Turks. According to contemporary accounts of the conquest, when the Ottoman leader Sultan Mehmed II came to the Hagia Sophia, he recognized its beauty and saved it from destruction. To Muslims, the Christian God and the Muslim God are the same, so Mehmed made the church a mosque—following a long tradition in the Middle East of continuing the use of sacred spaces. Minarets, towers from which the Muslim call to prayer is issued, were added at the four corners of the building, and Arabic writing was placed beside the ancient Greek iconography.

The second set of images (Figure 1.7 and Figure 1.8) show the Hagia Sophia as it stands today, having also been a museum and now serving as a mosque once again. The building tells a tale spanning hundreds of years and highlights many fascinating aspects of the region’s history. But without the context, its meaning would be far less clear.

Documentary Sources: Competing Narratives

Textual, or written, primary sources are considered the best possible resource for historians. They tend to offer both far more context and far more information than other types of sources, and sometimes clues about the writer’s intent. But even they must be approached with method and scrutiny. We must evaluate the author, audience, intent, and context in order to accurately interpret a primary source document. Some questions you might ask about the author include the following: Who wrote the piece and what is their background? What was important to the author? Why might the author have written what they did? In some cases, the answers will be fairly obvious. In others, a deeper inspection might reveal hidden motives. You must also take into account the planned audience for a document: For whom was it written? Was it meant to be public or private? Is it a letter to a friend or an essay submitted for publication? For a modern example, is it a text to a friend or to a mother? Texts will one day be a source for historians to use, but knowing who sent them, and to whom, will be essential to interpreting them correctly. (For fun, search online using the term “misinterpreted texts.”)

In addition to considering the audience, you should think about the intent: Why was the document written? Was it intended to be a factual account of an event? Was it meant to persuade? Is it a complete falsification? Often people write things that present them in the best light rather than reveal weaknesses.

Finally, you should reflect on the circumstances of the document’s creation. Some questions you may want to ask include the following: What is the general time period of the document, and what was that time like? What was happening when the individual wrote the document? Was there any sort of intimidation or distress? Is it a time of war or peace? Is there religious conflict? Is there an economic crisis? A health crisis? A natural disaster? Could the writer have been fending off an attack or lobbying for one? Are we missing other perspectives or voices we would like to hear?

The answers to these questions will shape your interpretation of the primary source and bring you closer to its true meaning. Most text-based sources have meanings beyond the obvious, and it is the historian’s job to uncover these. Be sure to keep these questions in mind throughout this course and whenever you undertake historical research or are considering the accuracy of information you encounter (Figure 1.9).

To gain experience using these questions, consider the two accounts in Child Labor in Great Britain, both recorded in the Hansard, the official report of debates in Parliament and dealing with the same subject from different perspectives. According to the first account, which is recorded as a direct speech delivered to Britain’s House of Commons (one of the two chambers of Parliament) on March 16, 1832, by reformer Michael Sadler, children who worked in textile factories suffered terribly. The second account, which is a reporting of the speech delivered to the House of Commons by one of Sadler’s opponents, John Thomas Hope, argues that child labor is not necessarily a bad thing. What should historians do with such competing texts? How do they decide what each one adds to the true story of child labor in the Industrial Revolution? If you were to read only one of these accounts, what important information or point of view would you miss? As you read, keep these questions in mind.

DUELING VOICES

Child Labor in Great Britain

In the 1830s and 1840s, Great Britain was rapidly industrializing, and workers including children were laboring in factories and mines. Many British people pressed Parliament to limit child workers’ time to no more than ten hours per day. In the first excerpt below, reformer Michael Sadler urged the House of Commons to regulate children’s labor. In the second, one of Sadler’s opponents, John Thomas Hope, argues that child labor in textile factories should not be regulated.

The parents who surrender their children to this infantile slavery may be separated into two classes. The first of these, and, I trust, by far the most numerous, consists of those who are obliged, by extreme indigence, so to act, but who do so with great reluctance and with bitter regret: themselves, perhaps, out of employment, or working at very low wages, and their families, therefore, in a state of great destitution, what can they do? The Overseer, as is in evidence, refuses relief if they have children capable of working in factories whom they refuse to send there. They choose, therefore, what they deem, perhaps, the lesser evil, and reluctantly resign their offspring to the captivity and the pollution of the mill: they rouse them in the winter morning, which, as the poor father says before the Lords’ Committee, they “feel very sorry” to do—they receive them fatigued and exhausted, many a weary hour after the day has closed—they see them droop and sicken, and, in many cases, become cripples and die, before they reach their prime: and they do all this, because they must otherwise suffer unrelieved, and starve.

—Michael Sadler, speech to the House of Commons, March 16, 1832, as recorded in the Hansard

[Mr. John T. Hope] doubted, in the first place, whether a case of necessity for parliamentary interference was fairly made out. . . . It was obvious, that if they limited the hours of labour, they would, to nearly the same extent, reduce the profits of the capital on which the labour was employed. Under these circumstances, the manufacturers must either raise the price of the manufactured article, or diminish the wages of their workmen. If they increased the price of the article, the foreigner would enter into competition with them. . . . [Hope] was informed that the foreign cotton manufacturers, and particularly the Americans, trod closely upon the heels of our manufacturers. If the latter were obliged to raise the price of their articles, the foreign markets would in a great measure be closed against them, and the increased price would also decrease the demand in the home market. To avoid these ruinous consequences the manufacturers would, in all cases where it was possible to dispense with their labour, cease to employ children at all, and employ a greater number of adults than before. [Michael Sadler] seemed to consider this an advantageous course; but [Hope] could not concur with that opinion, because the labour of children was a great resource to their parents and a great benefit to themselves. . . . It was, therefore, on these grounds, because, he doubted in the first place, whether Parliament could protect children as effectually as their parents; secondly, that he did not think a case for parliamentary interference had been made out; and thirdly, because he believed, the Bill would be productive of great inconvenience, not only to persons who had embarked large capital in the cotton manufacture, but even to workmen and children themselves, that he should feel it his duty to oppose the measure.

—John Thomas Hope, speech to the House of Commons, March 16, 1832, as recorded in the Hansard

- According to Michael Sadler, why is it wrong to employ children in textile factories? How does he use language to convey to the other members of Parliament the difficult conditions of factory labor?

- What arguments does John Thomas Hope use to oppose limiting the number of hours children can work? How does he try to persuade other members of Parliament to support his position?

- Why may the reporter have chosen to present Hope’s speech in the third person instead of in the first person, as he did for Sadler’s? Does this make Hope’s speech a less reliable source for a historian to rely upon for evidence?

- Records of parliamentary debate were available to the public to read. In what way might this have influenced what these politicians said and how they framed their arguments?

Textual Sources: The Importance of Language

The different types of language used in a source are clues to its interpretation. Linguists call the use of language rhetoric. Rhetorical choices, decisions about the way words are used and put together, are often deliberate and intended to achieve a certain outcome. For example, think about the way you talk to a professor versus the way you talk to a friend. We must closely examine the rhetorical choices in any primary document to correctly interpret it. To practice this skill, consider the 1887 speech given by Senator George G. Vest, a Democrat from Missouri, regarding whether women in the United States should be given the right to vote in Senator Vest on Women’s Suffrage and the guiding questions that follow.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Senator Vest on Women’s Suffrage

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, governments debated whether women should be given the right to vote. Opponents such as Senator George G. Vest, Democrat of Missouri, claimed they acted in women’s and society’s best interests by denying women suffrage. In 1887, when Vest delivered this speech to Congress, Democrats tended to be anti-Black and anti-immigrant, and they found their greatest support in the rural south. How does Vest depict himself as a supporter of women? Where is his anti-immigrant bias revealed?

If this Government, which is based on the intelligence of the people, shall ever be destroyed it will be by injudicious, immature, or corrupt suffrage. If the ship of state launched by our fathers shall ever be destroyed, it will be by striking the rock of universal, unprepared suffrage. [. . .]

The Senator who last spoke on this question refers to the successful experiment in regard to woman suffrage in the Territories of Wyoming and Washington. Mr. President, it is not upon the plains of the sparsely settled Territories of the West that woman suffrage can be tested. Suffrage in the rural districts and sparsely settled regions of this country must from the very nature of things remain pure when corrupt everywhere else. The danger of corrupt suffrage is in the cities, and those masses of population to which civilization tends everywhere in all history. Whilst the country has been pure and patriotic, cities have been the first cancers to appear upon the body-politic in all ages of the world. [. . .]

I pity the man who can consider any question affecting the influence of woman with the cold, dry logic of business. What man can, without aversion, turn from the blessed memory of that dear old grandmother, or the gentle words and caressing hand of that dear blessed mother gone to the unknown world, to face in its stead the idea of a female justice of the peace or township constable? For my part I want when I go to my home— [. . .] the earnest, loving look and touch of a true woman. I want to go back to the jurisdiction of the wife, the mother; and instead of a lecture upon finance or the tariff, or upon the construction of the Constitution, I want those blessed, loving details of domestic life and domestic love. [. . .]

I believe [women] are better than men, but I do not believe they are adapted to the political work of this world. I do not believe that the Great Intelligence ever intended them to invade the sphere of work given to men, tearing down and destroying all the best influences for which God has intended them. [. . .]

Women are essentially emotional. It is no disparagement to them they are so. It is no more insulting to say that women are emotional than to say that they are delicately constructed physically and unfitted to become soldiers or workmen under the sterner, harder pursuits of life.

What we want in this country is to avoid emotional suffrage, and what we need is to put more logic into public affairs and less feeling. There are spheres in which feeling should be paramount. There are kingdoms in which the heart should reign supreme. That kingdom belongs to woman. The realm of sentiment, the realm of love, the realm of the gentler and the holier and kindlier attributes that make the name of wife, mother, and sister next to that of God himself.

I would not, and I say it deliberately, degrade woman by giving her the right of suffrage. I mean the word in its full signification, because I believe that woman as she is to-day, the queen of the home and of hearts, is above the political collisions of this world, and should always be kept above them.

—George G. Vest, a speech to the 48th Congress, January 25, 1887

- According to Vest, why is he opposed to women’s suffrage?

- What language does Vest use to flatter women? What stereotypes does he evoke?

- How does Vest use language to contrast the public world of men with the domestic world presided over by women?

Hidden in History

Historians begin their work with a research question and seek to find the sources necessary to build an authentic narrative that answers it. One challenge is that written sources are undeniably valuable but often leave out important details. For example, many speak only of the lives of elites. It is not terribly difficult to find information about kings, queens, and other rulers of the past, but what of their families? Their servants? What of the ordinary people who lived under their rule?

Some groups of people remain hidden in our account of history because few records talk about their lives and experiences. Historians of the 1960s began to revolutionize the discipline by studying history “from the bottom up.” In other words, they began to focus on just those groups that had long been ignored. They used sources like church records, newspapers, and court hearings to illuminate the lives of the poor and illiterate. Court hearings were one venue in which the words of people from all backgrounds were recorded as they served as witnesses and as accused. Mothers and fathers also sought out those who could write letters for them to get pardons for loved ones convicted of crimes. These kinds of sources shed light on those whose voices were rarely heard, either while they lived or after they died. Great strides have been made in the field of social history, which looks beyond politics to the everyday aspects of life in the past. But it remains difficult, lacking records, to represent women, the poor, and minority communities on an equal footing with those who have traditionally held power.

These kinds of limitations can also apply to regions of the western world. Civilizations with long-standing and abundant historical documents often have more complete histories than others. Much is known, for example, about European history and Chinese history, both of which have deep roots in the written word. Europe, after all, had Herodotus, and China had Sima Qian. Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century BCE, is called the father of history in the West; he wrote the history of the Greco-Persian wars. Sima Qian, born in the middle of the second century BCE, is referred to in China as the father of history for his work Records of the Grand Historian, a sweeping history of the Han dynasty. The Middle East and India also have rich textual histories. In Africa and Latin America, the historical record is less full.

In the case of Latin America, the historical record was significantly altered when the Europeans arrived. Believing that much of the writing of Indigenous people that they found spoke of a religion and culture they meant to replace, the conquerors deliberately destroyed it. Writing Africa’s history is complicated by both its size and its diversity, as well as its colonial past. Due to the extremes of climate, surviving written documents and even archaeological evidence are not easily found, and what exists of written history is often tainted by the bias of the colonial observers who wrote it. New scholarship is emerging in both regions, generated by historians who look with fresh eyes and seek to understand history as it was. To gain some insight into the way history is relevant to the present, read Chinua Achebe on the Value of Indigenous History and consider the questions posed.

THE PAST MEETS THE PRESENT

Chinua Achebe on the Value of Indigenous History

The following is an interview with the noted Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe (1930–2013) in The Atlantic. Achebe, author of several important books including Things Fall Apart, which explores the impact of British missionary work in Nigeria, speaks to both the historic legacy of colonialism—the practice of controlling another people or area, usually for economic gain—and the need to first see ourselves independently and then in relation to others (Figure 1.10).

But, of course, something doesn’t continue to surprise you every day. After a while I began to understand why the book [Things Fall Apart] had resonance. I began to understand my history even better. It wasn’t as if when I wrote it I was an expert in the history of the world. I was a very young man. I knew I had a story, but how it fit into the story of the world—I really had no sense of that. Its meaning for my Igbo people was clear to me, but I didn’t know how other people elsewhere would respond to it. Did it have any meaning or resonance for them? I realized that it did when, to give you just one example, the whole class of a girls’ college in South Korea wrote to me, and each one expressed an opinion about the book. And then I learned something, which was that they had a history that was similar to the story of Things Fall Apart—the history of colonization. This I didn’t know before. Their colonizer was Japan. So these people across the waters were able to relate to the story of dispossession in Africa. People from different parts of the world can respond to the same story, if it says something to them about their own history and their own experience.

—Chinua Achebe in Katie Bacon, “An African Voice,” The Atlantic

- Try to sum up Chinua Achebe’s words in one sentence.

- In what ways do you think colonialism has influenced the writing of history?

a document, object, or other source material from the time period under study

a document, object, or other source material written or created after the time period under study

the study of how historians have already interpreted the past

the use of images and symbols in art

the way words are used and put together in speaking or writing

a field of history that looks at all classes and categories of people, not just elites