Chapter 10.2 The Spread of Communism

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how the Korean War began

- Explain why the United States took part in the wars in Indochina

In the immediate postwar period, Europe was the focus of US anti-communist anxiety. The United States expended billions of dollars in Marshall Plan aid to stave off the expansion of communism there. It was in Asia, however, that the policy of containment was most strongly challenged.

The Korean War

In 1949, the CCP’s People’s Liberation Army decisively defeated the forces of the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China, which had retreated to the island of Taiwan. On October 1, 1949, Chinese leader Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in a ceremony in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The United States refused to recognize the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) government as legitimate and maintained that Nationalist-led Taiwan was the “real” China. Mao was undeterred. He pledged industrial development, universal education, equality between the sexes, land reforms for peasants, and civil liberties for all, including freedom of expression. Mao and the CCP moved quickly to enact their promises, beginning immediately on the task of giving peasants ownership of the land they worked.

Along with making dramatic changes in China’s domestic policy, Mao also plotted a new course for China in foreign policy. In February 1950, the PRC and the Soviet Union signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance. Under its terms, they were to combat any renewed Japanese aggression, work to advance their mutual interests, and refrain from entering into any alliances that were hostile to the other party. All this was part of China’s new “Lean to One Side” foreign policy position, in which the country would favor socialist nations and assist those seeking to free themselves from control by imperialist powers. China soon found its new commitments tested by the need to support a fellow communist nation and counter a threat to its own borders in Korea.

On August 15, 1945, the nation of Korea, which had been occupied by Japan during World War II and had been a Japanese colony for many years before that, was divided in half at the thirty-eighth parallel of latitude. The United States assumed responsibility for disarming the southern part of the Korean peninsula, and the Soviet Union took on the task of disarming the northern half. At the Moscow Conference held in December 1945, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union agreed that they and China would jointly govern Korea for a period of five years, after which it would be reunified and given its independence. The Korean people’s opposition to the division of their nation and its subjection to foreign rule was ignored.

In the years since the original division of the nation, however, North Korea’s Communist Party, supported by the Soviet Union, had grown in power and refused to participate in the election. Given this opposition, in May 1948 elections to a Constitutional Assembly were held only in South Korea. A constitution was drafted, and the authoritarian anti-communist Syngman Rhee was elected president in July. In August, Rhee proclaimed the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK). Soon afterwards elections were held in North Korea, and a separate government for the new Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established with communist Kim Il-sung as its leader.

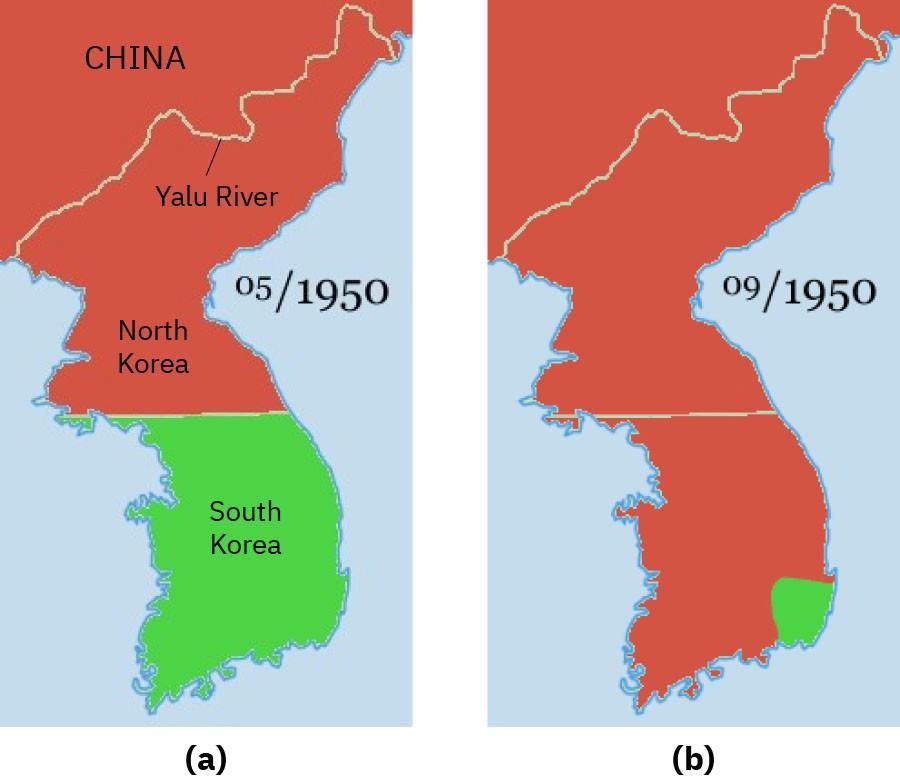

On June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) of North Korea invaded South Korea, confident of welcome. The ROK troops were unable to halt their advance, and within two days Seoul, the capital of South Korea, had fallen. The United States was taken by surprise. South Korea was not considered of vital importance to US security. However, Japan was, and President Truman, in keeping with the domino theory, believed a stable non-communist Korea was necessary to protect Japan.

The UN Security Council responded quickly. It condemned North Korea’s invasion of South Korea, and after a brief debate, on June 27 it issued Resolution 83, calling on the UN’s members to resist North Korean aggression. The Security Council’s actions could have been prevented by a veto of one its five permanent members: China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. However, since the Nationalists’ loss in the Chinese civil war, the United States had insisted that China’s seat on the council belonged to Taiwan, not to the People’s Republic of China, and the Soviet Union had boycotted the council’s meetings in protest. It was thus unable to stop the resolution from passing.

The United States suspected the invasion of South Korea had been a ploy by the Soviets to test the US response to an act of armed communist aggression. But Stalin had in fact warned Kim against it. Unwilling to start a war with the United States in Asia, he advised Kim to seek assistance not from Moscow but from Mao, whose CCP forces North Korea had aided in the Chinese civil war. Thus, while the United States immediately dispatched air and naval forces to Korea, the Soviet Union sent nothing. Initially Kim did not need assistance, though, and North Korean troops swiftly overran nearly the entire Korean peninsula, with ROK, UN, and US forces clinging to the area around the port of Pusan in the south (Figure 10.9).

The situation was reversed in September 1950 when US troops led by General Douglas MacArthur landed behind KPA lines at Incheon. Seoul was swiftly retaken, and Rhee returned to power. On October 19, 1950 Chinese forces crossed the Yalu River. By December, Chinese and North Korean forces had sent UN and US troops into retreat, back across the thirty-eighth parallel into South Korea. A cease-fire proposed by the UN was rejected by the Chinese forces, and fighting raged through the harsh Korean winter.

By July 1951, the war had turned into a deadly stalemate near where it began, along the thirty-eighth parallel. On July 27, 1953, the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed. To prevent the recurrence of hostilities, a Korean Demilitarized Zone was established, roughly along the thirty-eighth parallel, to be patrolled by North and South Korean forces, and US troops remained in South Korea as a deterrent to future North Korean aggression.

Like many of the proxy wars of the Cold War, in which the troops of nations allied with the United States and the Soviet Union faced off against one another rather than risk direct conflict between the superpowers, the Korean War was futile. Approximately three million people died in the three-year conflict, most of them Korean civilians who either were caught in the crossfire or became victims of starvation and disease, and all Korea’s cities lay in ruins. No territory was gained by either side, and no political transformation occurred in either the North or the South. The country remained divided, with North Korea adopting an isolationist policy that left it cut off from the West.

Southeast Asia and the Origins of the Vietnam War

The lessons of Korea also strengthened the US commitment to oppose the spread of communism in Vietnam. Following the end of World War II, France wished to reclaim control of Vietnam, which had been its colony before being seized by Japan in 1940. However, the Vietnamese nationalist group the Viet Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh, wished to seize the opportunity of Japan’s surrender to proclaim their country’s independence. The Viet Minh had fought the Japanese during World War II and had often assisted the US military. Ho Chi Minh fully expected that the United States would support them.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Ho Chi Minh Proclaims Independence

On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed Vietnam’s freedom from French rule. In his speech, excerpts of which follow, he stated a long list of grievances of the Vietnamese people against the French colonialists and argued that the Vietnamese people should be free to rule themselves:

In the autumn of 1940, when the Japanese fascists violated Indochina’s territory to establish new bases in their fight against the Allies, the French imperialists went down on their bended knees and handed over our country to them. Thus, from that date, our people were subjected to the double yoke of the French and the Japanese. Their sufferings and miseries increased. The result was that, from the end of last year to the beginning of this year, from Quảng Trị Province to northern Vietnam, more than two million of our fellow citizens died from starvation.

On March 9 [1945], the French troops were disarmed by the Japanese. The French colonialists either fled or surrendered, showing that not only were they incapable of “protecting” us, but that, in the span of five years, they had twice sold our country to the Japanese.

[. . .]

For these reasons, we, the members of the Provisional Government, representing the whole Vietnamese people, declare that from now on we break off all relations of a colonial character with France; we repeal all the international obligation that France has so far subscribed to on behalf of Viet-Nam, and we abolish all the special rights the French have unlawfully acquired in our Fatherland.

The whole Vietnamese people, animated by a common purpose, are determined to fight to the bitter end against any attempt by the French colonialists to reconquer the country.

We are convinced that the Allied nations, which at Tehran and San Francisco have acknowledged the principles of self-determination and equality of nations, will not refuse to acknowledge the independence of Vietnam.

A people who have courageously opposed French domination for more than eighty years, a people who have fought side by side with the Allies against the fascists during these last years, such a people must be free and independent!

—Ho Chi Minh, Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

- What arguments does Ho Chi Minh make for Vietnam being an independent country?

- Why does he believe the Allies will support him?

Members of the US military who had worked with Ho liked and respected him. However, while he was primarily a nationalist and no one questioned his patriotism, he was also a communist. Wanting to stand firm against what it saw as Soviet-directed communist expansion, the United States also wished to support its ally France, whose help it believed it needed to prevent the spread of communism in Europe. Thus, as the First Indochina War raged between French troops and the supporters of Ho Chi Minh, the United States assumed most of France’s financial burden for the war. China and the Soviet Union gave assistance to Ho’s forces.

Following its defeat in 1954 at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France granted independence to Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. According to the Geneva Accords, the peace treaty ending the war, Vietnam was divided along the seventeenth parallel of latitude with the assumption that, following national elections in 1956, it would be reunified (Figure 10.10). Ho Chi Minh governed the North and was expected to be the popular candidate in both North and South. The South was governed by a figurehead, the emperor Bao Dai, and his prime minister, Ngo Dinh Diem.1 Diem, a strong anti-communist, came from a family of wealthy Roman Catholics in a country where most people were poor and Buddhist. Before the elections, approximately one million Vietnamese Catholics from the North moved to the South, fleeing communist rule and bolstering support for Diem, who was backed by the United States. But he remained unpopular with the majority of Vietnamese people.

Ngo Dinh Diem had no intention of relinquishing power, however; he argued that South Vietnam had not signed the Geneva Accords and so was not bound by them. In 1955, a referendum was held in South Vietnam. The rigged results revealed that Diem won. He was a ruthless politician who allowed no opposition and used the military to attack South Vietnamese Buddhists and students who protested his rule. His regime restricted Buddhist activities. In 1963, Buddhist monks set themselves on fire in public places to draw attention to Diem’s brutal and corrupt regime. When foreign journalists questioned why the monks felt the need to engage in such dramatic protest, Diem’s sister-in-law and South Vietnam’s unofficial First Lady, Madame Nhu, compared the suicides to “barbecues.”

The Second Indochina War, sometimes simply called the Vietnam War, began in 1959 when the North Vietnamese Communist Party, seeking to unify the country under communist rule, called for a “people’s war” against the government of South Vietnam. North Vietnam received support from both China and the Soviet Union. Also helping the North was a group of South Vietnamese communists, many of whom had relocated to North Vietnam following the Geneva Accords. These men and women officially formed the National Liberation Front (NLF) in North Vietnam in 1960. Popularly known as the Viet Cong, the NLF returned to the South to organize peasants and begin an insurgency against the government of South Vietnam and the United States. US president John F. Kennedy responded by continuing to do what his predecessors had done: he sent money and advisers to the South Vietnamese government but refused to commit ground troops. The situation would fester until erupting a few years later into full blown war.

Footnotes

- 1 Vietnamese names are written with the family name first. The given name comes last. Ngo Dinh Diem is usually referred to by historians by his given name Diem instead of his surname Ngo in order to differentiate him from his brothers Ngo Dinh Thuc and Ngo Dinh Nhu, who also played an important political role in Vietnam.

wars fought by allies of the Soviet Union and the United States to avoid risking a direct conflict between the two superpowers during the Cold War