Chapter 2.1 The Protestant Reformation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the causes of the Protestant Reformation

- Describe differences between Protestant and Catholic beliefs

- Discuss the spread of Protestantism in Europe and the wars of religion

- Describe the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation

When Columbus set sail across the Atlantic in 1492, the people of western and central Europe, regardless of their country or language, were united by a common religion. In the same year as Columbus’s momentous voyage, Spain defeated the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula and expelled Jewish people from the land. Muslims were given a brief respite, but in 1501 they too were ordered to leave or to convert to Catholicism. With the exception of small Jewish communities in the Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands) and the German lands, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the people of western and central Europe were uniformly Roman Catholics. Challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church were brewing, however, and the passage of less than a century found Europeans hopelessly divided over matters of faith as the result of an event known as the Protestant Reformation.

The Origins of the Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517, but its seeds had been sown years earlier. Over the course of the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church had grown richer, and its higher clerical offices had become dominated by people motivated more by the desire for wealth and power than by spiritual concerns. Although Europe’s peasants remained devoutly attached to their faith, critics claimed that popes acted less like Christ’s representatives on earth and more like secular princes, intervening in European political affairs and even commanding armies. Members of the clergy often lived lavishly in palatial surroundings and dressed themselves in silks and furs. Some had mistresses and illegitimate children, who were often given positions in the church. Wealthy families often purchased church offices for their members, and some men held bishoprics (areas under the authority of a bishop) in more than one place at a time by hiring other men to perform their offices. Secular rulers, kings, and princes jealous of the church’s power sometimes vied with the pope for control of the churches in their territory and welcomed opportunities to reject the church’s authority.

During the fifteenth century, in the city-states of northern Italy, an intellectual movement called humanism had taken hold. Humanism stressed the value and dignity of human beings, and its scholars believed that, through the study of the philosophy, history, and literature of ancient Greece and Rome, people could improve themselves and live a “good life,” which, in turn, would improve the societies in which they lived. Italian humanists were often devout Christians, and their study of ancient authors did not lead them to reject the teachings of the Catholic Church.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, northern European scholars championed a form of humanism whose explicit goal was to make people better Christians. Northern Renaissance humanism, also called Christian humanism, stressed the study of the works of Greece and Rome together with the teachings of the early Christian fathers to improve the state of the human soul. The goal of learning was to awaken an inner sense of piety, and northern Renaissance humanists such as Desiderius Erasmus encouraged people to use Christian teachings as a guide to daily life. This inner transformation, they believed, was superior to engaging in such outer forms of religious devotion as going on pilgrimage or fasting at prescribed times of the year. By becoming better Christians, people would ultimately reform the church.

Discontent among some European Catholics and an interest in spiritual transformation in northern Europe set the stage for a German monk named Martin Luther to try to eliminate the questionable practices of the medieval Roman Catholic Church. Luther’s actions began the Protestant Reformation.

In 1517, Luther, then a professor at the University of Wittenberg in Germany, became outraged when the Dominican friar Johann Tetzel began to sell

indulgences in Wittenberg, authorized by Albert, archbishop of the city of Mainz. Indulgences were a way to reduce or even cancel the time after death during which people needed to suffer in purgatory to atone for their sins before reaching heaven. These rewards could be earned by performing actions of great religious merit, such as going on Crusade. However, the church also taught that the pope controlled a store of merit amassed by Jesus and the Christian saints, whose virtue was so great they had entered heaven with grace left over. The church could allot this “extra” virtue to someone else in the form of an indulgence.

Luther had long been obsessed with thoughts of achieving salvation, the goal of all Christians. He was horrified at the idea that sinners might believe they could enter heaven not through repentance or God’s mercy but by paying for an indulgence. He drafted ninety-five arguments explaining why the sale of indulgences was wrong, and according to many historians, he then nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the castle church at Wittenberg. He also distributed printed copies throughout Germany and sent a copy to Archbishop Albert, who passed it along to Rome.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

The Ninety-five Theses

Martin Luther argued that the sale of indulgences was wrong. He believed only God could grant forgiveness and that humans could do nothing to ensure their salvation, which depended entirely upon God. This is known as the doctrine of justification by faith. Luther also said the pope had no control over purgatory and that there was no foundation in the Bible for the belief that the merit amassed by Jesus and the saints could be given to others. His intent in the Ninety-five Theses was to spark a discussion within the church that would lead to reform. Following are several of the theses.

6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring and showing that it has been remitted by God; or, to be sure, by remitting guilt in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in these cases were disregarded, the guilt would certainly remain unforgiven.

35. They who teach that contrition is not necessary on the part of those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessional privileges preach unchristian doctrine.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

38. Nevertheless, papal remission and blessing are by no means to be disregarded, for they are, as I have said (Thesis 6), the proclamation of the divine remission.

41. Papal indulgences must be preached with caution, lest people erroneously think that they are preferable to other good works of love.

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

51. Christians are to be taught that the pope would and should wish to give of his own money, even though he had to sell the basilica of St. Peter, to many of those from whom certain hawkers of indulgences cajole money.

—Martin Luther, Ninety-five Theses

• What does Luther say about the forgiveness of sin?

• What evidence do you see that Luther had not yet completely broken with Catholic teachings?

• Do you see evidence that Luther is trying to be conciliatory toward the pope? Do you see anything likely to anger the pope?

Although Luther had probably merely wished to reform the practices of the church, such as ending the sale of indulgences, and not to spark a rebellion against the church, his actions were not seen that way. In 1518, he was summoned by church authorities to answer questions regarding the position he expressed in the Ninety-five Theses. At a meeting in the German city of Augsburg, Luther denied that the church had the power to distribute merits amassed by Jesus and the saints. His beliefs were officially condemned by Pope Leo X, and he was ordered to recant, which he refused to do. In 1521, he was excommunicated (excluded from participating in the life of the church).

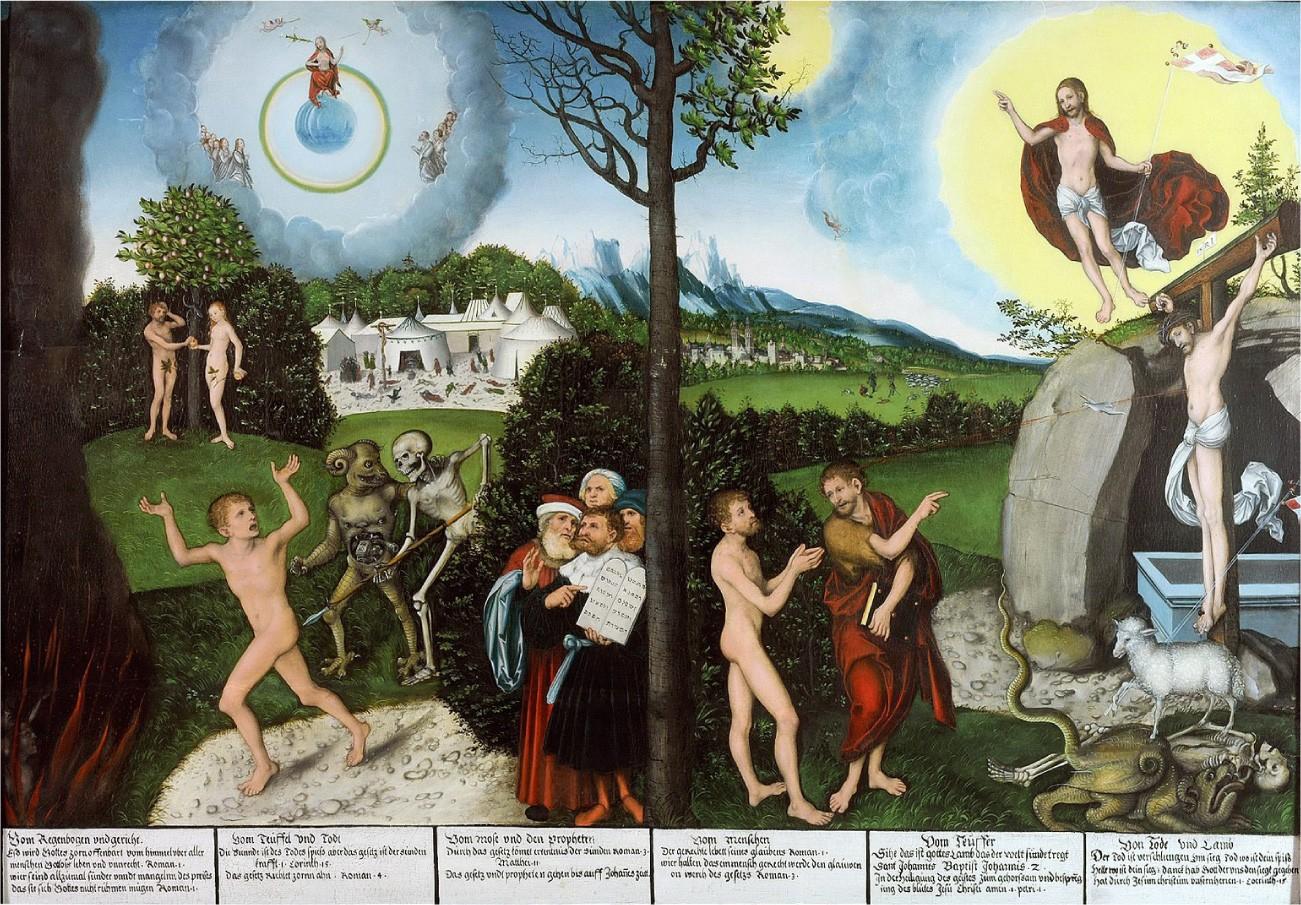

The version of Christianity that developed from Luther’s ideas, and that formed the basis for what became the Protestant faith, differed from the official teachings of the Roman Catholic Church in important ways. The Catholic Church taught that salvation was achieved through a combination of religious faith and good works. Buying an indulgence was regarded as a good work because the money went to the church. Luther taught that faith alone was sufficient for salvation and that humans were unable to work toward their own redemption, which depended entirely upon God (Figure 2.4). Furthermore, adherence to centuries’ worth of Catholic tradition was not necessary to be a good Christian. Luther contended that scripture alone should be the source of Christian belief and practice. His followers thus abandoned many traditional Catholic practices, including clerical celibacy. Luther, a monk, married Katharina von Bora, a former nun, and began a family. Protestants also called for the abolition of religious orders of monks and nuns. A life in the clergy, which the Catholic Church had proclaimed the greatest of all callings, was considered no better than the pursuit of any other vocation in life. The printing press with movable type, developed in Europe during the Renaissance, aided Martin Luther in his efforts to spread his message, and thousands of copies of Luther’s writings circulated throughout Europe.

Calvinists, Anabaptists, and Anglicans

Efforts to silence Martin Luther were unsuccessful, and the new form of Christianity called Protestantism spread throughout the German-speaking lands. By the end of the sixteenth century, it had become entrenched throughout western and central Europe as well. Often the new religion was welcomed by rulers as a reason to reject the pope’s authority, and Luther called upon the German princes to do so.

The Catholic Holy Roman emperor Charles V (who was also Charles I of Spain) steadfastly opposed Protestantism. However, the 1555 Peace of Augsburg secured for rulers in the empire who were Lutheran (as Luther’s followers were called) the right to establish Lutheranism as the official religion within their lands if they wished. A prince’s subjects were obliged to support the church he chose. Many rulers in northern Germany became Lutheran, but in Austria and Bavaria, in the southern part of the German-speaking lands, the Roman Catholic Church retained its power. No other religions were accommodated.

In Switzerland, the ideas of the reformation that Luther began were embraced by Ulrich (Huldrych) Zwingli in the city of Zurich. Zwingli, who had been a priest, called for radical changes, such as a rejection of the Catholic tenet of transubstantiation, which held that Jesus was physically present in the communion wine and wafer consecrated during every Mass. Even Martin Luther had not gone so far. Zwingli also preached against fasting in the period before major religious holidays and called for religious imagery to be removed from churches. He banned organs from churches, shut monasteries and convents, and had the Bible printed in German rather than Latin. Zwingli also called for an end to clerical celibacy and proclaimed that the Bible never referred to purgatory. He was killed in 1531 in a conflict between the Catholic and Protestant areas of Switzerland.

Among those inspired by Zwingli’s ideas was Konrad Grebel, a Swiss merchant. Grebel was especially moved by Zwingli’s claims that baptism, through which people were admitted into church membership, should be delayed until adulthood when a person is capable of making the choice to renounce sin. Finding Zwingli too slow in reforming the Christian community in Zurich, however, Grebel established his own religious movement in 1524, the Swiss Brethren.

The Swiss Brethren was one of several Anabaptist churches—churches rejecting infant baptism in favor of adult baptism—that were established in the sixteenth century, primarily in central Europe and the Low Countries. Because baptism was believed to remove the taint of original sin (the transgression of Adam and Eve), infant baptism was the norm among Catholics and most Protestants as well. Anabaptists, however, believed that only adults could meaningfully renounce sin and make a declaration of faith. Thus, only adults could make the conscious decision to become Christians. But since people could be baptized only once, anyone rebaptized as an adult was violating a tenet of the Catholic faith.

Other Anabaptist movements included the Hutterites, the Mennonites, and the Amish, which broke from the larger Mennonite movement in the seventeenth century. Besides believing in adult baptism, Anabaptist groups advocated the separation of church and state and tended to be pacifists. Because of their refusal to hold public office, serve in the army, or accept secular rulers’ right to control religious affairs, Anabaptists were widely feared by most European rulers and were often subject to violent attacks.

Another center of Protestant thought was the city of Geneva in what is now Switzerland. The city’s religious leader, John Calvin, had been raised a Catholic in France, but he became a Protestant either before or shortly after fleeing to Switzerland to escape persecution for his beliefs. His ideas were similar to those of Martin Luther, but they differed in one crucial respect. Calvin espoused a doctrine known as predestination, which held that God had predetermined which souls would be granted salvation upon death and which were destined for hell. No person could ever know for certain whether they were saved or damned, and there was nothing they could do to ensure salvation. Calvinists embraced the doctrine, and despite its denial of human agency, they strove to lead a rigidly moral lifestyle focused on hard work and piety, seeking, in their ability to live like people destined for heaven, reassurance that they had in fact been saved. They rejected dancing, public drunkenness, gambling, and obscene speech as ungodly and fit for punishment by a special tribunal called the Consistory. Calvinism spread rapidly outside Geneva and found adherents in the Netherlands, who established the Dutch Reformed Church; in Scotland, where the Presbyterian Church was formed; and in France, where its adherents were called Huguenots.

Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, and the Anabaptist leaders were true believers in the doctrines they espoused. The English Reformation, however, was of a different character. In England, reform was initially imposed from the top down, not by a committed convert but by a king looking for an expedient way to exchange one queen for another.

Until the moment he decided to remove himself from under the pope’s authority, Henry VIII of England had a reputation as a devout Catholic and a critic of Luther. He was married to Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, who were famous for defeating the Muslim kingdom of Granada and expelling Jewish and Muslim people from the Iberian Peninsula. Henry and Catherine’s marriage had produced only one living child—a daughter, Mary. Although English law did not exclude women from inheriting the throne, Henry wanted to take no chances with the succession following his death and desired a son whose rule would go unchallenged.

Accordingly, against Catherine’s wishes, Henry sought an annulment of his marriage so he might marry Anne Boleyn, who he believed would give him sons. Unlike a divorce, which the Catholic Church did not permit, an annulment simply declared a marriage null and void on the grounds it had never been legitimate. Henry argued that, because Catherine had first been married to his late elder brother Arthur, Catholic Church law prohibiting the marriage of close relatives should never have allowed her and Henry to wed. When the pope refused to annul the marriage, Henry declared the English church no longer bound by the pope’s authority. In 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, establishing the Church of England with the English monarch as its head. The archbishop of Canterbury, the highest spiritual authority in the land, finally granted the annulment of Henry and Catherine’s marriage. Henry had already quietly married Anne in time to see her give birth to a daughter, Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I).

Under Henry’s leadership, the Church of England (also known as the Anglican Church) remained largely Catholic in terms of both doctrine and ritual. Henry closed England’s monasteries, but his failure to purge the English Church of all elements of Roman Catholicism did not sit well with many Protestants. Upon Henry’s death, his son Edward VI, whose mother Jane Seymour had been Henry’s third wife, became king. Because Edward was still a minor, England was governed by regents who took steps to make the Anglican Church more Protestant, a move with which the young Edward agreed. Priests were allowed to marry. The practice of using rosary beads in prayer was denounced. Church processions were prohibited, and statues and stained-glass windows were removed from churches. The mass service was reformed, eliminating many Roman Catholic rituals, and the English-language Book of Common Prayer, published in 1549, laid out the new church service. Ministers who refused to use the Book of Common Prayer risked being removed from their positions and imprisoned.

The Catholic Reformation and the Wars of Religion

The leaders of the Catholic Church did not sit idly by as its members deserted it for new faiths. The Catholic Reformation, also called the Counter-Reformation, was the Catholic Church’s effort to address Luther’s challenges as well as to effect other necessary reforms. One means to do so was the 1545 Council of Trent. There, Europe’s bishops and other clerics affirmed that both good works and faith were required for salvation and that both scripture (as interpreted by the church) and tradition were acceptable sources of authority. The council also affirmed the doctrine of transubstantiation. Aware of very real problems within the church, the council undertook a series of reforms as well. Indulgences were retained, but their sale was forbidden. The council prohibited church officials from appointing relatives to church offices, limited bishops to holding office in only one bishopric, and took steps to improve the education of Catholic clergy and curb their luxurious habits.

Another aspect of the Catholic Reformation was the creation of new religious orders. Founded by the Spanish noble Ignatius of Loyola, the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits, assumed a number of tasks, chiefly the education of young Catholic men. They also undertook responsibility for the conversion of non-Christians to Roman Catholicism and for acting as advisers to the Catholic rulers of Europe. Unlike other religious orders, the Jesuits did not have a female branch. Instead, the Ursuline order of nuns, founded a few years before, undertook the education of young women.

Although the Catholic Reformation undoubtedly prevented the defection of many Catholics to Protestant churches, the new churches continued to gain adherents in many parts of Europe. At times, this was a peaceful process. At other times, wars erupted as devout Catholics did battle with equally devout Protestants to protect what both sides believed was the only true expression of Christian faith.

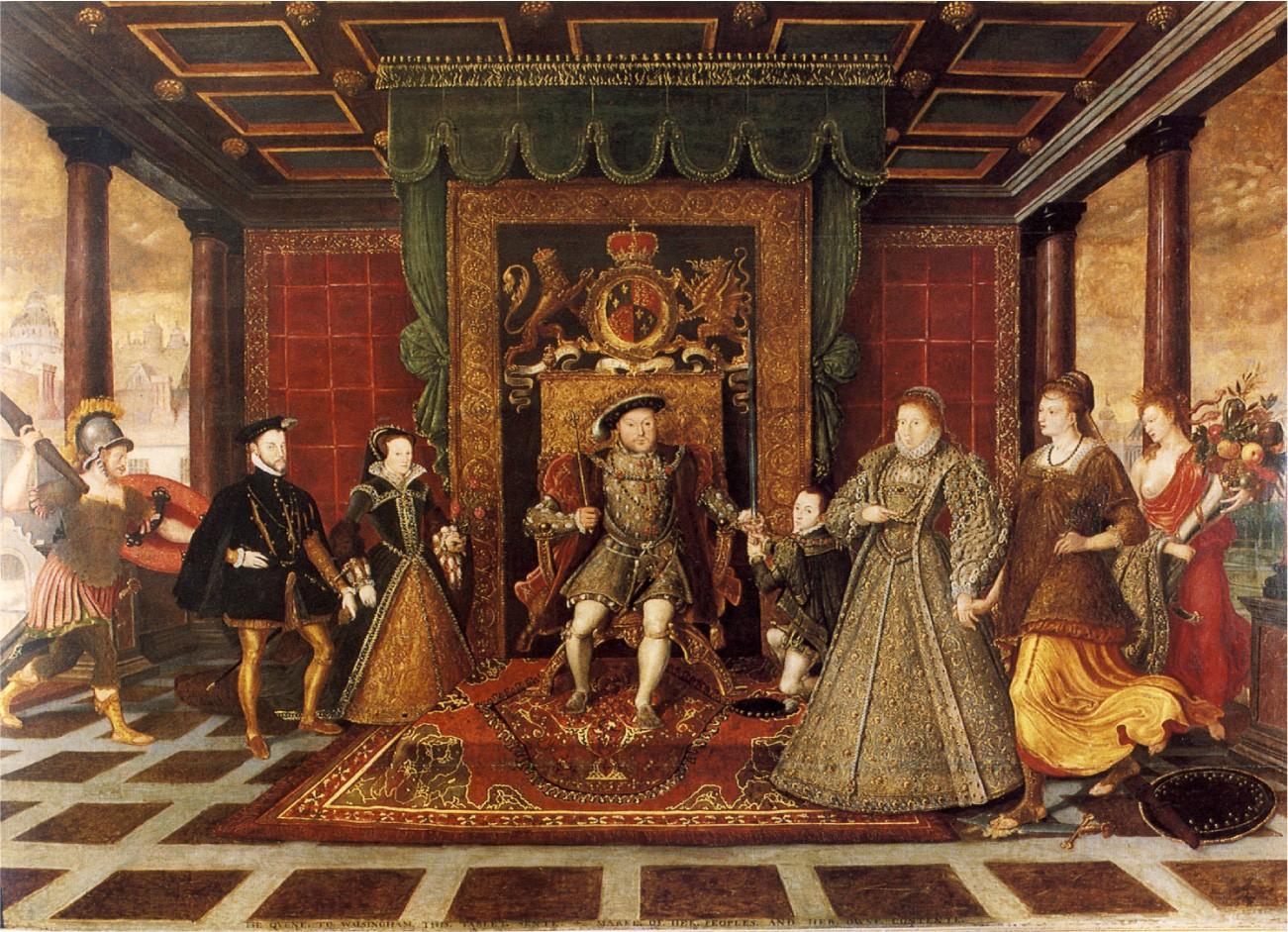

The transition from Catholicism to Protestantism in England was more peaceful than elsewhere. While Henry VIII’s Catholic daughter Mary I, the child of Catherine of Aragon, occupied the throne following her brother Edward’s death, Protestants were persecuted, and hundreds were executed as the queen tried to restore England to the Catholic Church. Mary died in 1558 before she could achieve this, however. Her younger half-sister, Elizabeth I, wished to govern an orderly, stable country, and while late in her reign she did persecute Catholics she felt posed a threat to her Protestant rule, she adopted a relatively moderate approach to religion during her early years on the throne (Figure 2.5).

Parliament’s 1558 Act of Supremacy once again declared the Church of England separate from the Roman Catholic Church. The following year, the Act of Uniformity of 1559 brought back the Book of Common Prayer as the only legal form of worship in England. Some concessions were made, however, to those who did not wish to abandon Catholic ritual. The condemnation of the pope contained in an earlier version of the book was removed, and the communion ritual was described in a way that avoided making a clear statement about transubstantiation. Clergy could continue to wear traditional Catholic robes and ornaments.

During Elizabeth’s reign, English Calvinists, known as Puritans, attempted unsuccessfully to move the Church of England even further from the doctrine and ritual of the Catholic Church. Many clergy in the English church were Puritans, and they objected to wearing Catholic robes during church services and making the sign of the cross during baptism. By the 1570s and 1580s, Puritans had also come to oppose the structure of the Church of England, in which the monarch was the head of the church. They believed churches should be independent and governed by groups of elected elders instead of a king or queen. Elizabeth was unwilling to change the manner in which the Church of England was governed, however. During the reign of her successor James I, Puritans who wished to separate from the Church of England (known as Separatists) began to depart England for places, including mainland Europe and North America, where they believed they would be able to establish ideal Christian communities. In the reign of Charles I, James’s son, other Puritans also began to leave.

LINK TO LEARNING

English Puritans who immigrated to British colonies in North America used a book called The New England Primer (opens in new tab) to teach their children to read while also imparting religious lessons. This website presents images of the book, first printed in the 1680s. Pages 15 to 18 contain the alphabet and short rhymes to help children remember the letters: “A. In Adam’s fall we sinned all.”

Outside England, the dispute over whether a kingdom should be Catholic or Protestant could be quite violent. In 1572 in France, warfare between Huguenots and Catholics culminated in the August 23 St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, assassinations targeting prominent Huguenots who had come to Paris for a royal wedding.

Peace was restored only when the Huguenot Henry IV succeeded to the throne of France, converted to Catholicism (the religion of the majority of French people), and issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598. The edict established Catholicism as the official religion of France but also granted Huguenots the right to worship as they chose.

In the Spanish Netherlands, Philip II of Spain, son and heir of Charles V, fought against Calvinist rebels. War raged from 1568 until a truce was signed in 1609. (After Philip’s death in 1598, his son Philip III fought on after him.) Peace was restored, but the seven northern provinces established their independence from Spain as the United Provinces of the Netherlands. The Netherlands was not the only place in which Philip II, who regarded himself and Spain as defenders of Catholicism, fought to maintain the church’s supremacy. In 1588, he launched a naval attack on England with the intent of restoring it to the Catholic Church and ending its support for Protestant rebels in the Spanish Netherlands. The invasion failed. The Spanish armada was famously outmaneuvered by the smaller, faster English ships, and as the remaining vessels started for home by sailing north around Scotland and Ireland, most were destroyed by a storm.

The wars of religion continued into the seventeenth century. From 1618 to 1648, the Thirty Years’ War between Catholic and Protestant states raged in the Holy Roman Empire. As German Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists fought one another, other European countries entered the fray. Sweden, a Lutheran land, supported the Protestant German rulers, as did the United Provinces of the Netherlands. Denmark also entered the war in the hopes of gaining German territory to offset its losses to Sweden in recent conflicts. France joined in on the side of the Protestants, primarily in an effort to become the preeminent power in Europe. Despite the multinational nature of the combatants, battles were fought almost entirely within the German lands, whose people suffered as armies of mercenaries destroyed farms and villages. In the end, the German Protestants were victorious, and France had become the dominant country in western Europe. The Peace of Westphalia, which ended the war in 1648, established the independence of each of the entities, numbering nearly one thousand, that had made up the Holy Roman Empire.

a movement, also known as northern Renaissance humanism, that stressed the study of the works of Greece and Rome and the early Christian fathers to awaken individual piety

a way to reduce or cancel the time after death during which people needed to suffer in purgatory

to atone for their sins before reaching heaven