Chapter 2.4 The Atlantic Slave Trade

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the workings of the triangular trade

- Compare slavery in Africa and slavery in the Americas

- Discuss the way market forces influenced the development of labor-intensive agriculture in the Americas

- Describe the human toll of slavery

To extract the greatest possible wealth from their American colonies, the nations of Europe planted them with cash crops Europeans craved but could not produce at home. To maximize profit, they drove workers hard without regard for their health or safety. When Indigenous peoples and European servants could not satisfy their demands, they turned to enslaved labor taken from Africa. The latter decision affected the lives of millions of people for centuries to come.

Slavery and the Triangular Trade

One of the largest migrations in history took place between the late fifteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as Europeans forcefully transported approximately twelve million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas to provide labor for Europe’s economic enterprises. Some two million people died on the voyages across the Atlantic. The survivors made possible the extraction of wealth from European colonies on which the system of mercantilism was based.

The majority of Africans brought across the Atlantic were destined to labor on sugar plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil. Many enslaved Africans were also sent to the Spanish colonies in South America; relatively few went to the North American mainland, mostly Mexico. European colonizers had originally considered using enslaved Indigenous peoples to perform the difficult and dangerous labor of harvesting sugar cane and other cash crops, but these efforts failed. Indigenous people died in large numbers from infectious diseases, leaving too few to labor in the fields. On the island of Hispaniola, for example, where both the Spanish and the French established sugar plantations, the native Taíno population was at least several hundred thousand strong when Columbus arrived in 1492. By 1514, however, only about thirty-two thousand Taíno remained. Some had been deliberately killed by the Spanish, and others had died from hard labor and poor living conditions after being enslaved. The vast majority, though, had died of disease.

For Europeans, the ideal laborers would be people as unfamiliar with the terrain as they were because, unlike enslaved Indigenous people, who knew the best places to hide, they could more easily be recaptured if they ran away. In addition, they would be less affected by many of the infectious diseases from which Europeans suffered. Although Europeans did not understand what caused immunity, they knew those who had previously contracted certain diseases like smallpox and survived would not contract that disease again. They also knew, from long contact with Africans, that they did not die from European diseases in the same numbers that Indigenous Americans did. In the European view, Africans satisfied both their key requirements.

European indentured servants would also have fit the bill, but the hot Caribbean climate and diseases like malaria and yellow fever, brought from Africa with cargoes of enslaved people, led to high death rates among Europeans within the first year and discouraged most others from immigrating there. Indentured servitude did not satisfy the labor needs of tobacco planters in Virginia and Maryland either, where the death rate among Europeans was also high. Although some indentured servants were convicts sentenced to be transported to the colonies, the vast majority left Europe voluntarily, but they were not enough. In addition, a French law passed in 1664 that restricted planters’ right to beat their indentured servants made servants a less desirable form of labor in the eyes of French colonizers. Thus, Europeans eager to extract a profit looked to Africa as the solution, and to slavery instead of indentured servitude. They believed Africans were physically better suited to hard labor than Europeans were, and Africans could also be enslaved for a lifetime, ensuring a constant supply of field hands.

The Portuguese, already using enslaved Africans to grow sugar on islands off the coast of Africa, were the first to bring them in large numbers to the Americas. The initial Portuguese voyage to do so transported two hundred Africans to the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, on the island of Hispaniola, in 1525. Most were forced to grow sugar for Portuguese colonizers in Brazil or were sold to the Spanish for this purpose. Captured Africans were also sold to the Spanish to work in mines in Mexico and Peru or to be employed as domestic servants. Soon the British, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Danes were also exporting captives from Africa to produce sugar, rice, indigo, tobacco, and, by the eighteenth century, coffee in the Americas.

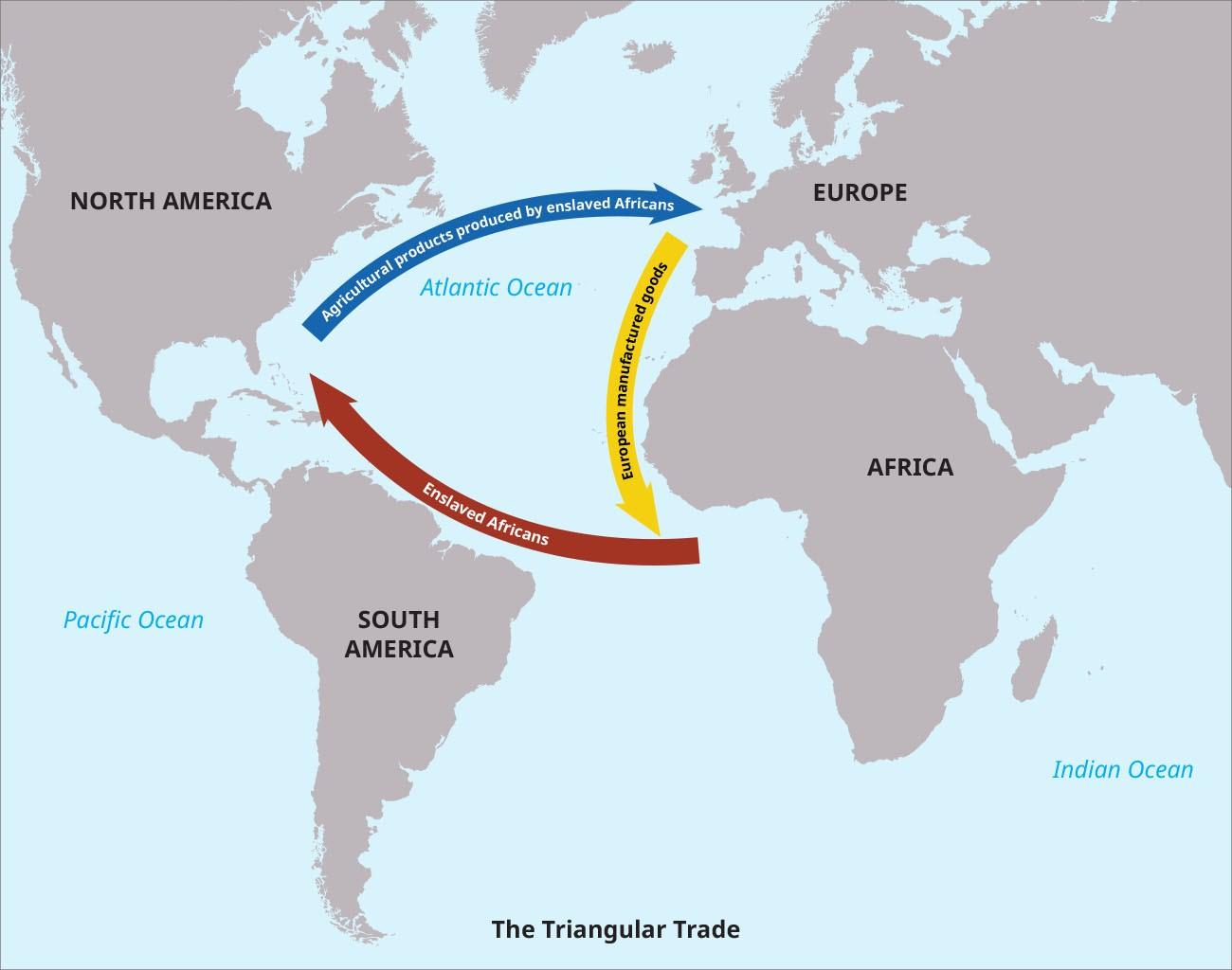

Although the economic system that relied on the labor of enslaved Africans to grow sugar and other crops for European colonizers in the Americas was a complex one, for purposes of simplification, it is often characterized as the triangular trade because it linked three regions (the Americas, Europe, and West Africa) in a network of exchange (Figure 2.20). The shipment of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic was one leg of the triangular trade. In the first leg, Europeans exchanged manufactured goods with African traders for enslaved Africans.

The enslaved people were then shipped across the Atlantic to European colonies in the Americas. This journey was called the Middle Passage because it was the middle (or second) leg of the three-legged exchange. The money earned from the sale of enslaved Africans in the colonies was used to purchase the products grown by existing enslaved laborers. In the third leg of the triangle, those goods were shipped to Europe or to a European country’s other American colonies, where they were transformed into finished products.

For example, English slave traders exchanged rum for captives in African ports. The captives then traveled across the Atlantic in chains to England’s Caribbean colonies, where they were sold to the owners of plantations who set them to work growing sugar cane. The plantation owners then shipped molasses, a by-product of sugar production, to other English settlers in the colony of Massachusetts, who transformed it into rum and shipped that to England. English ship captains in Africa then exchanged rum along with manufactured products like cloth, guns, and ammunition for captives. African slave traders used the guns to capture more people to send along the Middle Passage, and the cycle continued. Enslaved people were the base on which the triangle rested. Without the sugar, tobacco, coffee, indigo, and rice produced through their labor, the trade would have collapsed.

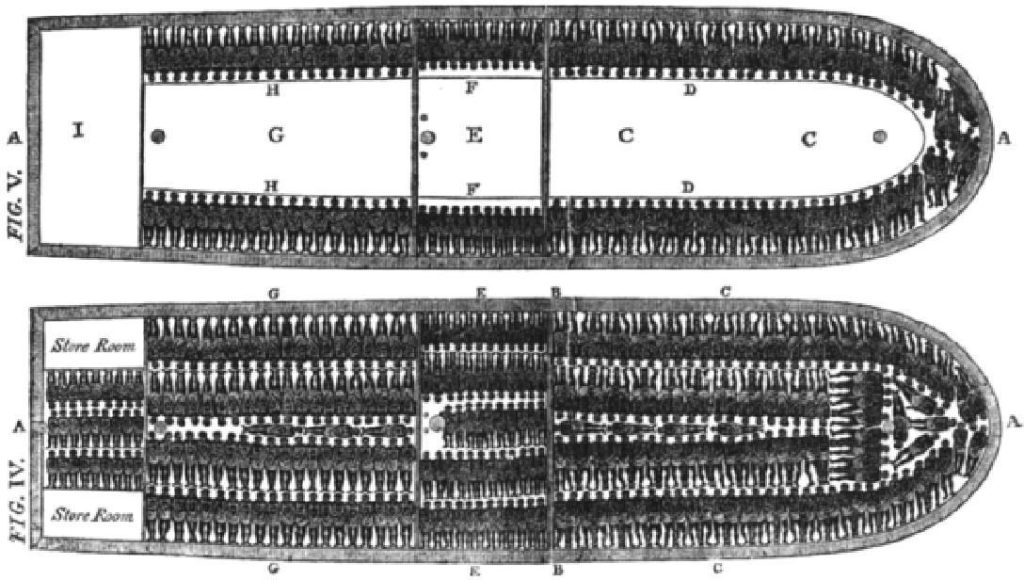

The human toll of the transatlantic slave trade was immense. Conditions on the Middle Passage were brutal, and some ships held as many as five to six hundred people. Some captains, knowing that 10 to 20 percent would die on the voyage, packed as many people as possible into the hold, hoping enough would survive to earn them a good profit. In the hold, men were separated from women and children and were chained side by side on their backs, sometimes with only a few inches of space above them (Figure 2.21). In 1713, the Royal Africa Company, a British company, instructed captains that enslaved people should be allotted a space five feet long, eleven inches wide, and twenty inches high. The implication was that captains usually packed people into even smaller spaces.

During the voyage, sailors gave the enslaved people food and water usually once a day. There were no facilities for bathing, and men and women alike relieved themselves in buckets or tubs that often overturned in rough seas. Ventilation was poor, the stench was horrible, and the heat excruciating. At times crews would bring the enslaved Africans onto the deck for fresh air and make them jump and dance to exercise their muscles, since buyers would not pay high prices for those who looked weak. Removing captives from the hold was always a risk for the crew, however, since this was the time when a revolt was most likely to take place. Slave ship captains harshly punished any attempt at rebellion. Taking enslaved people to the deck was also risky because many used the opportunity to commit suicide rather than endure the misery on board the ship or the uncertain fate that awaited them. Some captains strung nets below the ships’ rails to catch those who jumped overboard.

Illness was the slave ship captains’ constant fear. In the close quarters of the ship, infectious disease could sweep like wildfire, and every person who died reduced the captain’s profit. The most feared of all diseases was trachoma, an infection of the eyes that did not kill but left its victims blind. Enslaved people who could not see would not be purchased. Even more frightening was the possibility that the infection would spread to the crew. If the sailors lost their sight, everyone on board faced a slow death from starvation as the ship sat adrift in the water, unable to reach any port.

Slave voyages were often heavily insured against loss. The captain of the Zong took full advantage of this. When bad weather slowed his ship’s voyage across the Atlantic in 1781, members of the crew and the enslaved cargo began to die of illness. Realizing that the ship owner’s insurance policy would pay for captives lost at sea but not for those who died of sickness, the captain ordered 132 enslaved people thrown overboard to drown.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Olaudah Equiano Describes the Middle Passage, 1789

At the age of 11, enslavers captured Olaudah Equiano in his Ibo village in what is now Nigeria. The enslavers brought him to the coast for forced transportation to Barbados. In the following passage, Equiano describes his experience of the “Middle Passage.” This excerpt is from his 1789 autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which was a widely-read book used to advocate for the abolition of slavery.

The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions, too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke (which was very different from any I had ever heard), united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country. When I looked round the ship too, and saw a large furnace of copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little, I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those who had brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and long hair. They told me I was not, and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in a wine glass; but being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One of the blacks therefore took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, threw me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced, having never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this, the blacks who brought me on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore, which I now considered as friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in preference to my present situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind, still heightened by my ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, Death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced anything of this kind before, and, although not being used to the water, I naturally feared that element the first time I saw it, yet, nevertheless, could I have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not; and besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down to the decks, lest we should leap into the water; and I have seen some of these poor African prisoners most severely cut, for attempting to do so, and hourly whipped for not eating. This indeed was often the case with myself.

In a little time after, amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which in a small degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of these what was to be done with us? They gave me to understand, we were to be carried to these white people’s country to work for them. I then was a little revived, and thought, if it were no worse than working, my situation was not so desperate; but still I feared I should be put to death, the white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal cruelty; and this not only shown towards us blacks, but also to some of the whites themselves. One white man in particular I saw, when we were permitted to be on deck, flogged so unmercifully with a large rope near the foremast, that he died in consequence of it; and they tossed him over the side as they would have done a brute. This made me fear these people the more; and I expected nothing less than to be treated in the same manner. I could not help expressing my fears and apprehensions to some of my countrymen; I asked them if these people had no country, but lived in this hollow place (the ship)? They told me they did not, but came from a distant one. “Then,” said I, “how comes it in all our country we never heard of them?” They told me because they lived so very far off. I then asked where were their women? had they any like themselves? I was told they had. “And why,” said I, “do we not see them?” They answered, because they were left behind. I asked how the vessel could go? They told me they could not tell; but that there was cloth put upon the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and then the vessel went on; and the white men had some spell or magic they put in the water when they liked, in order to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed at this account, and really thought they were spirits. I therefore wished much to be from amongst them, for I expected they would sacrifice me; but my wishes were vain — for we were so quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make our escape.

While we stayed on the coast I was mostly on deck; and one day, to my great astonishment, I saw one of these vessels coming in with the sails up. As soon as the whites saw it, they gave a great shout, at which we were amazed; and the more so, as the vessel appeared larger by approaching nearer. At last, she came to an anchor in my sight, and when the anchor was let go, I and my countrymen who saw it, were lost in astonishment to observe the vessel stop—and were now convinced it was done by magic. Soon after this the other ship got her boats out, and they came on board of us, and the people of both ships seemed very glad to see each other. Several of the strangers also shook hands with us black people, and made motions with their hands, signifying I suppose, we were to go to their country, but we did not understand them.

At last, when the ship we were in had got in all her cargo, they made ready with many fearful noises, and we were all put under deck, so that we could not see how they managed the vessel. But this disappointment was the least of my sorrow. The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep much more happy than myself; I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as often wished I could change my condition for theirs. Every circumstance I met with served only to render my state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty of the whites. One day they had taken a number of fishes; and when they had killed and satisfied themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our astonishment who were on the deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat, as we expected, they tossed the remaining fish into the sea again, although we begged and prayed for some as well we cold, but in vain; and some of my countrymen, being pressed by hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no one saw them, of trying to get a little privately; but they were discovered, and the attempt procured them some very severe floggings.

One day, when we had a smooth sea, and a moderate wind, two of my wearied countrymen, who were chained together (I was near them at the time), preferring death to such a life of misery, somehow made through the nettings, and jumped into the sea: immediately another quite dejected fellow, who, on account of his illness, was suffered to be out of irons, also followed their example; and I believe many more would soon have done the same, if they had not been prevented by the ship’s crew, who were instantly alarmed. Those of us that were the most active were, in a moment, put down under the deck; and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the people of the ship as I never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat to go out after the slaves. However, two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the other, and afterwards flogged him unmercifully, for thus attempting to prefer death to slavery. In this manner we continued to undergo more hardships than I can now relate; hardships which are inseparable from this accursed trade. – Many a time we were near suffocation, from the want of fresh air, which we were often without for whole days together. This, and the stench of the necessary tubs, carried off many. During our passage I first saw flying fishes, which surprised me very much: they used frequently to fly across the ship, and many of them fell on the deck. I also now first saw the use of the quadrant. I had often with astonishment seen the mariners make observations with it, and I could not think what it meant. They at last took notice of my surprise; and one of them, willing to increase it, as well as to gratify my curiosity, made me one day look through it. The clouds appeared to me to be land, which disappeared as they passed along. This heightened my wonder: and I was now more persuaded than ever that I was in another world, and that every thing about me was magic. At last we came in sight of the island of Barbadoes, at which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us.

—Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (London: 1790), 51-54.

- What information can we learn about the Middle Passage from Equiano’s experience?

- Why did Equiano and others not try to escape the ship? Equiano describes in multiple passages that he and others “prefer death to slavery,” including several who threw themselves overboard. How was suicide a form of resistance to slavery?

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

The Slave Voyages website (opens in new tab) is a digital history project that examines the transatlantic and intra-atlantic slave trade. The site contains records and information compiled by researchers from throughout the world, including the details of more than 36,000 voyages. Examine the site, including the maps, timelines, statistics, and the voyages database.

African and North American Slavery

The captives purchased by European ship captains were sold by other Africans. Europeans did not introduce slavery to Africa; it had existed there for centuries before the triangular trade began. It was different in important ways, however, from the slavery that awaited Africans on the other side of the Atlantic.

Slavery existed in numerous African societies, and there were many ways in which a person could become enslaved. In some societies, slavery served as punishment for a crime. In others, people could be enslaved or sell their children into slavery to pay a debt. In times of hardship like famine, parents might sell children to more prosperous people to earn money to support themselves and ensure their children would be fed. In many societies, enslaved people were taken as prisoners of war.

Africans enslaved people primarily to enlarge their households, the basic economic units of society. Families suffered if they did not have enough able-bodied people to work in the fields or tend to herds, and slavery provided a solution. Some enslaved Africans remained with the slaveholder their entire lives, but others expected to regain their freedom. Those enslaved to pay a debt, for example, gained their freedom once the debt had been settled. Even people enslaved for life could participate fully in the life of the household or community. They could marry; their spouse might be free, and their children would be. They might own property, including enslaved people of their own. They were often well respected in the community, especially if they possessed important knowledge or skills. Africans regarded slavery as an unfortunate fate that might befall anyone; being enslaved did not imply an inherent difference or inferiority. The life of an enslaved person was not comfortable or easy, but it was not often what we think of when we consider Atlantic plantation slavery.

Slavery in the Americas was different. It was chattel slavery, in which one person is owned by another as a piece of property like an inanimate object. The enslaved had no status or legal rights as persons. They could be bought, sold, inherited, or given to another. They had no right to control their own bodies or their own labor, and they could be compelled to do whatever the slaveholder wished. Their status could be passed on to their children; in all the European colonies in the Americas, the child of an enslaved woman was born enslaved. Although chattel slavery also existed in Africa, this was the only form of slavery that existed in the Americas.

For centuries, Africans had participated in the trans-Saharan slave trade, selling prisoners in North Africa and on the Swahili Coast to be transported to destinations in the Mediterranean or the Middle East. The arrival of Europeans willing to pay large sums changed the focus of the African slave trade, however. Africans now captured and enslaved large numbers of other Africans with the intent of selling them to Europeans for transportation across the Atlantic. Wars were launched against rival peoples solely for the purpose of taking captives, and slave traders led expeditions into the interior of the continent to kidnap people who lived far away. Africans were not safe in their own homes. In the eighteenth century, slave traders kidnapped young Olaudah Equiano (later an abolitionist) and his sister as they played at home; while their parents were gone, strangers climbed over a wall into the courtyard of their house and carried the children away. Some people were tricked and sold to European slave traders by their own relatives.

Once captured, people were marched for days to one of the places on the coast where Europeans exchanged goods for human beings. Many died on the way. Slave traders commonly chained their captives together on the journey, and devices were sometimes fixed to captives’ necks so that if they managed to escape, they would die of thirst because they could not lower their heads into streams to drink. Once they reached the coast, the traders stripped them naked and shaved their heads to keep them free of lice. The traders then greased their bodies with palm oil to make them look fit and healthy when buyers came.

A number of slave trading ports flourished on the western coast of Africa from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Among them were Ouidah (Whydah), Grand-Popo, Jaquim, and Porto-Novo in modern Benin; Badagry in Nigeria; and Little Popo in Togo. In these ports, English, Dutch, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Danish, and Swedish traders and sea captains bargained with African slave traders for their captives. Some African city-states and kingdoms became wealthy from the slave trade, and their rulers protested only if their own people were taken. King Afonso of Kongo told the king of Portugal that, out of a desire for European goods, the people of his own kingdom were capturing their fellow Kongolese and selling them to Portuguese traders. He did not denounce the slave trade but asked only that the Portuguese bring their captives to officials of Kongo to be sure they were not free Kongolese wrongfully seized. According to King Gezo of Benin, “The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth . . . the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery.”

The transatlantic slave trade harmed those who remained in Africa as well as those who were taken. Families endured the emotional trauma of losing loved ones. Fear of falling prey to slave traders pervaded villages throughout West and Central Africa. Olaudah Equiano recalled that when adults in his village left for the fields, children stationed someone in a tree to keep watch for kidnappers while the others played.

The African economy suffered as well. Those most likely to be captured, men and women in the prime of life, had been contributing the greatest share of labor to their communities. When slave traders captured young adults, no one remained to care for children and the elderly, and fewer people were left to reproduce.

According to one model, between 1750 and 1850 no population growth occurred south of the Sahara Desert and north of the Limpopo River as a result of the loss of people to the slave trade. To compensate for the disappearance of so many young men, who were the laborers most preferred by plantation owners, many African ethnic groups adopted polygyny, allowing men to take multiple wives. The loss of men also necessitated that women adopt traditionally male economic roles.

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

Read this article by researcher Nathan Nunn (opens in a new tab) to learn more about the long-term effects of slavery on Africa.

Desire for the goods Europeans traded for enslaved people also had devastating consequences for Africa. The importation of European textiles, according to some historians, spurred the industrialization of the European textile industry while harming African cloth producers, who could not compete on quantity or price. Weavers continued to produce goods for local markets, but no continent-wide market for African textiles ever had an opportunity to develop because Europeans already dominated the field. There were similar consequences for the African metal industry.

These effects have been long-lasting. One scholar has demonstrated that the areas from which the most enslaved people were taken are today the poorest in Africa, though at the time of the slave trade they were among the most developed. They are also more prone to civil conflict today than other areas of the continent. Other studies have shown that people from ethnic groups most likely to have been subject to the slave trade are less likely to trust others than are people from less affected groups. This may be due at least in part to the slave trade’s breaking down of the social and political structures intended to protect people.

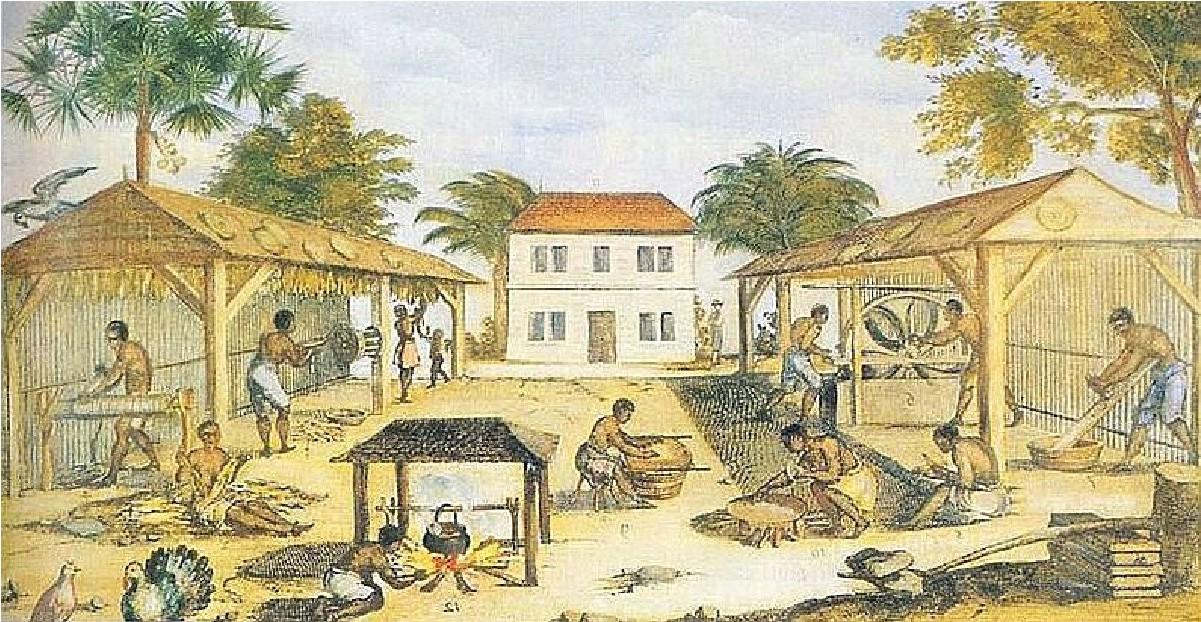

The Economics of Slavery

Those who reached their final destination faced an existence as hellish as they had experienced on the Middle Passage. The labor to which they were put was backbreaking and never-ending. Most of the crops grown by enslaved Africans in the Americas were labor intensive. At that time, tobacco seeds had to be planted by hand and the seedlings transplanted in the fields. At harvest time, workers stripped tobacco leaves from the plant, hung them to dry, and packed them in large barrels that they then rolled to the coast or a riverbank to be taken on board ship and transported to Europe (Figure 2.22).

Rice cultivation also required the transplanting of seedlings by hand. Enslaved people first cleared the undergrowth from swampland, built earthen dikes, and then flooded the cleared land with water. As they worked in the swampy waters, they were exposed to snakes and mosquitos carrying malaria and yellow fever.

Sugar, the most valuable crop grown by enslaved people, also required the most labor, and sugar plantations often contained hundreds of workers. With the exception of the very youngest and the very oldest, all of them toiled all day as part of large work gangs. The labor was grueling and dangerous. Sugar cane was densely planted, and undergrowth in the fields could hide snakes that bit workers. After fertilizing and weeding the cane, workers harvested it by cutting it close to the ground with machetes and then chopping it into smaller pieces to make it easier to remove from the fields. Machetes wielded in tired workers’ sweaty hands often slashed legs and feet. Workers might bleed to death or die when wounds became infected. People who worked too slowly were beaten.

Laborers then transported the cut cane to a mill to be crushed by heavy rollers that often caught and mangled workers’ hands. This had to be done very quickly, within twenty-four hours of cutting the cane, because the sap evaporated quickly. The workers boiled the crushed cane to extract a liquid that was clarified and crystalized into sugar, a process that required hours of standing next to roaring fires where workers were often scalded. To maximize profits, planters rotated production, so while sugar cane was growing in one field, it was being harvested in another. Because sugar cane rapidly depleted nutrients in the soil, laborers frequently also had to clear land for new fields. In addition to growing and processing sugar cane, enslaved people had to tend to the plantations’ buildings and livestock and cut the wood needed to cook the cane sap.

Slaveholders spent little money on food for the enslaved people, so laborers spent additional time tending their own gardens, fishing, and foraging for wild foods. To give them energy and dull their pain, slaveholders often gave them shots of rum, a plentiful beverage on a sugar plantation.

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

Visit the National Museums Liverpool site (opens in new tab) to learn more about slavery in the Caribbean and how archaeologists have learned about this institution.

BEYOND THE BOOK

Contrasting Images of Slavery

Few European painters created images of slavery. François-Auguste Biard of France and Agostino Brunias, who was born in Rome and lived on the Caribbean island of Dominica, were exceptions. The first painting that follows, by Brunias, shows women at the market (Figure 2.23). The women in the center wearing white may be free women of color, a favorite subject of this artist.

The second image, by Biard, was made approximately fifty years later, shortly before slavery was abolished (for the second time) in the French colonies (Figure 2.24).

- How do these paintings differ in subject matter and style?

- Brunias has been described as depicting slavery in a romantic way. Where do you see evidence of this in the painting shown here?

- What details in Biard’s painting might make viewers support abolition?

Infectious disease, overwork, poor diet, and injuries claimed large numbers of lives. Because infant mortality among enslaved people in the Caribbean was rampant, the enslaved population was not self-reproducing, and slaveholders had to buy more people each year to maintain their labor force. Prices were high. A healthy young adult might cost as much as an average European could earn in a year’s worth of labor. In 1684, planters in Santo Domingo (the Dominican Republic) paid six thousand pounds of sugar per enslaved African. Some 2,500 to 3,000 new captives were required each year. This differed substantially from the English North American mainland colonies where, because the work of growing and processing tobacco was less physically grueling, enslaved people did not die in such high numbers, and the population was able to grow through reproduction.

Despite the conditions in which they lived, enslaved people in the Americas managed to retain their dignity and humanity. Couples married and produced children, some of whom survived. They formed new kin networks, calling fellow laborers “brother” and “aunt” to replace the relatives from whom they had been taken. They created new religions with elements of various African practices and Christian elements learned from their enslavers. They combined foods brought from Africa with local ingredients to create new cuisines that reminded them of home. The influence of Africa persisted in the music, dance, and stories they created.

Enslaved people also resisted the slaveholders’ efforts to exploit them in numerous ways. They damaged tools, sabotaged machinery, and set fire to cane fields and barns full of sugar awaiting export to Europe. They ran away; in the mountains of Jamaica, runaways formed communities and lived in hiding. On several occasions, enslaved people rose up in armed rebellion, killing the slaveholders and overseers.

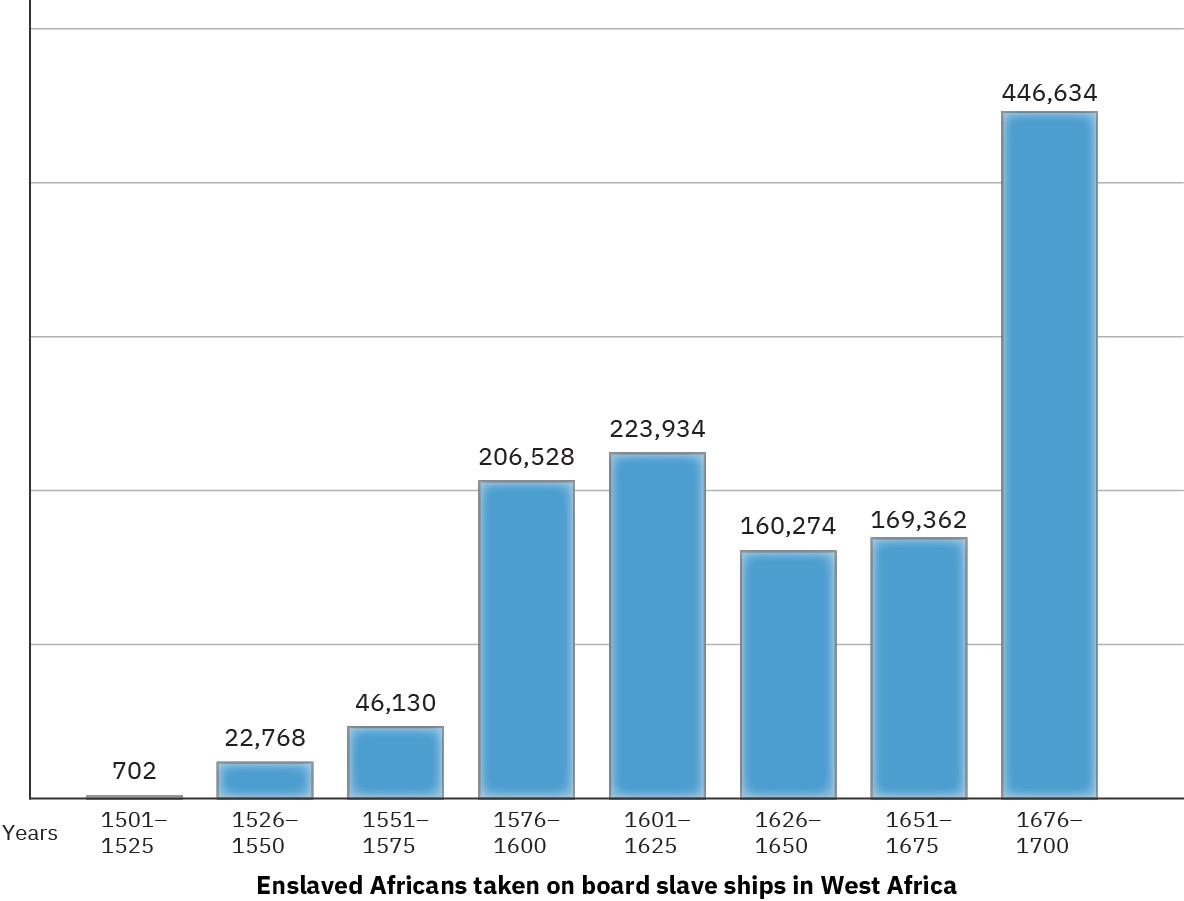

Largely unmoved by the misery of enslaved Africans, Europeans possessed an insatiable appetite for sugar that only grew as time passed. In 1650, planters in Barbados alone shipped about five thousand tons of sugar to England. Fifty years later, that amount had doubled. As the demand for sugar grew, so did the demand for enslaved laborers. Between 1450 and 1600, approximately 2,500 enslaved Africans a year were purchased by Europeans; in the sixteenth century, most of these people were sent to Hispaniola, Cuba, Brazil, and Venezuela. Beginning in the seventeenth century, however, as England, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark established sugar plantations in the Caribbean, the number of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas rose to some 18,680 per year (Figure 2.25). In the eighteenth century, by which time thousands of sugar mills dotted the coast of Brazil and the Caribbean islands, 61,330 people traversed the Middle Passage each year.

Forty-two percent were sent to labor in the Caribbean and 38 percent to Brazil. The British colonies of the North American mainland claimed only 4 to 5 percent of the total.

The trade in both sugar and enslaved people sustained numerous industries and employed thousands of people, creating great wealth for some. Shipbuilders, ship captains, and sailors found employment, as did dock workers, freight drivers, customs agents, and workers in sugar refineries. Bakers, pastry cooks, candy makers, and grocers all indirectly made money from sugar. People who made the barrels that held sugar and the other products produced by enslaved people—tobacco, rice, and indigo—profited, as did those who supplied inexpensive clothing, shoes, and foodstuffs like salted fish for enslaved people. Banks and insurance companies earned enormous sums as well, and those who owned large sugar plantations often invested their profits in other industries, built magnificent mansions, or bought luxury goods.

Such wealth was easily transformed into political power. Sugar planters in Britain successfully lobbied Parliament to protect their interests, and many planters went into politics, holding seats in the House of Commons and, by using their wealth to purchase titles and estates, the House of Lords. It was thanks to the sugar lobby in Parliament that the British navy began to give its sailors a daily ration of grog, a mixture of rum, sugar, and lime juice, increasing the profits of British sugar planters even more.

the trade in goods and enslaved people that took place between the Americas, Europe, and West Africa from the late fifteenth through the early nineteenth centuries

the middle (or second) leg of the three-legged triangular trade that carried enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas

a form of slavery in which one person is owned by another as a piece of property