Chapter 8.2 The Formation of the Soviet Union

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the Soviet Union’s early years and the structure of its government

- Analyze the effects of Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan on the Soviet economy

- Describe life in the Soviet Union under Stalin

Russia underwent massive political upheaval during the Bolshevik takeover in 1917. A bloody civil war was fought for the next three years before the Bolsheviks and their leader Vladimir Lenin were victorious. Russia was then reorganized as the Soviet Union in the early 1920s. Lenin’s early death created an opening exploited by Joseph Stalin, an autocrat who reshaped the “worker’s paradise” of the Soviet Union to bring it fully under his authoritarian control.

The Birth of the Soviet Union and the Rise of Stalin

After the Bolshevik seizure of the government and Russia’s hasty departure from World War I, Lenin moved to consolidate power in Russia. Civil war raged from 1918 to 1921 between the Red Army of the Bolsheviks and the White Army representing all the groups that opposed them, including the Russian upper classes, forces loyal to the monarchy, and Lenin’s enemies within the Russian Social Democrats, such as the Menshevik faction. Members of the White Army disagreed on whether they sought an anti-Bolshevik communist government or the return of a tsarist government. The Red Army, though smaller, had a focused goal and was better organized.

British, French, Japanese, and U.S. troops all invaded Russia in support of the White Army and stayed until 1920, but they were unable to stop the Bolsheviks from seizing control. The civil war ended in 1921 with the Bolsheviks in control. Approximately 1.5 million soldiers had died in the fighting, but the civilian death toll was substantially higher—about eight million.

During the civil war, Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership also sought to take over lands outside Russia that had been controlled by the now-deposed tsar. Lenin approached these regions with the goal of creating a federal state of republics governed by a soviet, an elected committee of workers’ representatives. Each republic in this new “Soviet Union” would represent an ethnicity and be nominally independent but ultimately under the central government’s control. Many of these areas fiercely resisted incorporation by the Bolsheviks.

In 1919, for example, the Red Army invaded Ukraine and faced strong resistance, but by 1920, the Bolsheviks had taken control. Belarus was also established as a Soviet republic fairly easily. Both Ukraine and Belarus had some autonomy but had to rely on Lenin’s government to direct foreign policy. Other areas, like the Caucasus, proved more contentious. Azerbaijan and Armenia were incorporated by the Bolsheviks in 1920. The government in Georgia was heavily Menshevik and resisted Bolshevik rule, but in 1921 the Red Army took control of this region as well. In 1922, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was established. It incorporated the country of Russia and the regions Russia had absorbed as soviet republics under a new centralized national government quite different from what the revolutionaries had envisioned only a few years before (Figure 8.8).

The Bolsheviks had used the civil war to strengthen their control over the economy. This included wielding oversight of industrialization and taking steps toward the elimination of private property. The national government decided what could be produced and rationed goods throughout the country. Such control was held up as necessary to meet government and military needs, but the focus on top-down administration vied with the revolution’s slogans about workers having more power under communism.

World War I and the civil war had created massive dislocations in the Russian economy. Industrial production had dropped significantly below prewar levels, as had agricultural production and particularly grain output. People were out of work, and prices had risen. The economy was essentially bankrupt. To combat these problems, Lenin abandoned the earlier economic approach, called war communism, and introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. The NEP kept the government in overall control of the economy, but it introduced some aspects of capitalism, such as giving peasants the ability to sell their produce on the market and allowing small businesses to operate through private, not state, ownership. This was not the pure socialist state Lenin had envisioned. Instead, it was an emergency response to significant hardships and growing discontent among the Russian people.

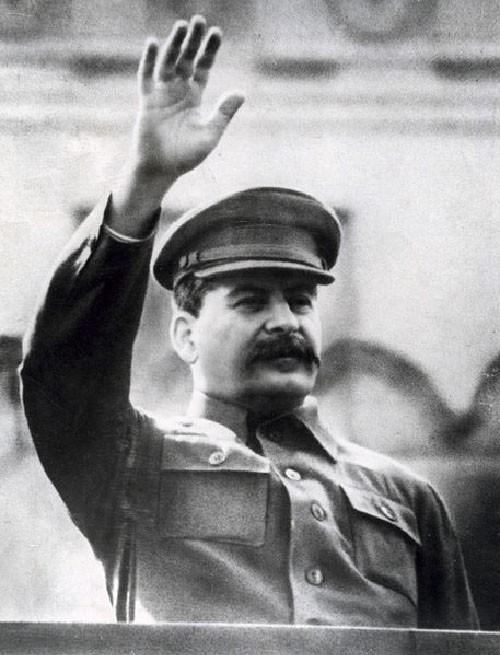

By the end of the civil war, Russia’s Communist Party bureaucracy had grown quite large and intricate. There were multiple layers of leaders, from the local through the regional and national levels. One who began to exploit his understanding and control of this bureaucracy was Joseph Stalin (Figure 12.9). Stalin had grown up in poverty in the Russian Empire’s state of Georgia. He adopted the surname Stalin in adulthood because it meant “man of steel,” and he became a Bolshevik in the early 1900s. In 1922, Stalin became the Communist Party’s general secretary. This was not a high-level position, but Stalin realized he could use it to consolidate power behind the scenes. He controlled all appointments within the party and could ensure that only those who agreed with him achieved these positions.

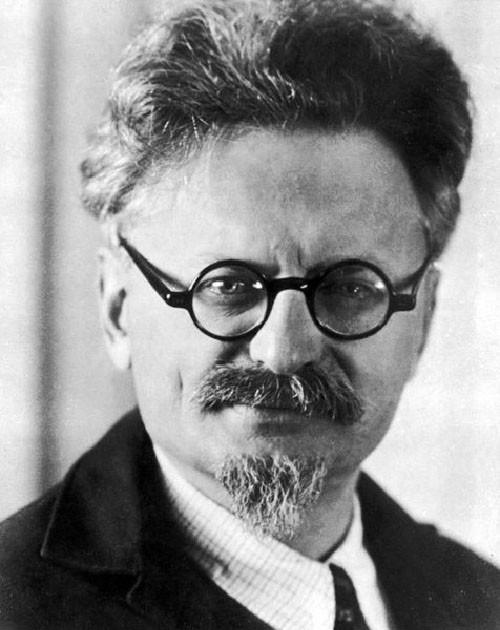

Lenin’s death in 1924 opened a power vacuum and a debate over the future of policy in the Soviet Union. There were two very different paths the country could follow. Favoring one path were leaders such as Leon Trotsky, the man responsible for making the Red Army a dependable fighting force during the civil war (Figure 12.10). Trotsky hoped to both increase industrialization and end the more capitalistic policies of the NEP. In particular, Trotsky hoped the Soviet Union could serve as an example to spur more revolutionary movements around the world. On the other side were those who wanted to continue the NEP and pursue a slower, less radical path to industrialization. Stalin, then in his forties, strove to keep out of these specific debates. He and Trotsky held opposing views on communist ideology and the future of the Soviet Union, but Stalin’s control over the Communist bureaucracy gave him leverage.

In 1927, Stalin expelled Trotsky from the Communist Party. In 1929, Trotsky was forced into exile. He was assassinated by a Soviet agent in Mexico in 1940. By the end of the 1920s, although the new Soviet government did seek to fulfill some of the promises Bolshevism had held out, the collective approach of the early years of the decade had devolved to one-man rule.

The First Five-Year Plan

Stalin’s domestic agenda was codified in the form of Five-Year Plans outlining economic achievements the Soviet Union was to have made by each plan’s conclusion. The timeline was ambitious, if not impossible. Yet officials tried to achieve the goals; they risked losing their jobs or even their lives for not meeting production quotas.

The first Five-Year Plan was designed to rapidly industrialize the Soviet Union. Stalin abandoned his earlier support of slow growth in light of the need to produce more farm equipment for the peasants and the desire to undercut those who had been advocating for more industrialization. Cities devoted to specific industries were developed and funded. Iron and steel production was to be raised dramatically under the plan, and new electrical power stations were to be built. Many of these goals were achieved, and overall industrial capacity increased by approximately 50 percent.

Stalin’s intention to exert state control over all aspects of life in the Soviet Union foundered when it came to agriculture. The collectivization of agriculture consisted of the shift from individual farms to large state-run farms, and when Communist Party officials moved to quickly meet production quotas that were increased after the first Five-Year Plan was implemented, they did so with little regard for the realities of agricultural production. The peasants heavily resisted the intrusion of government officials into their workdays. As the plan began to be implemented, they even resorted to violent means. The revolution had promised them better lives, but these would not be possible under the terms of the plan.

Across the country’s agricultural communities were a number of peasants labeled kulaks by the government. Kulaks had prospered under the more liberal policies of the NEP. In the early 1920s, Soviet policy had specifically defined a kulak as someone who hired seasonal farm laborers for an individual farm of twenty-five to forty acres. Very few farmers fell into this category, but they became scapegoats for Stalin. He blamed them for the difficulties in implementing collectivization and cast them as enemies of the state, which made them subject to arrest and even execution. Even their family members were prevented from holding certain jobs or pursuing university educations.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Collectivization in the Soviet Union

The following resolution was adopted during a Soviet Politburo meeting and details plans for punishing villages and kulaks who opposed collectivization. Many places opposed this policy and were seen as disloyal by government officials. As you read, note what government officials would be looking for and what types of punishments they planned to mete out.

In view of the shameful collapse of grain collection in the more remote regions of Ukraine, the Council of People’s Commissars and the Central Committee call upon the oblast executive committees and the oblast [party] committees as well as the raion executive committees and the raion [party] committees: to break up the sabotage of grain collection, which has been organized by kulak and counterrevolutionary elements; to liquidate the resistance of some of the rural communists, who in fact have become the leaders of the sabotage; to eliminate the passivity and complacency toward the saboteurs, incompatible with being a party member; and to ensure, with maximum speed, full and absolute compliance with the plan for grain collection.

The Council of People’s Commissars and the Central Committee resolve:

To place the following villages on the black list for overt disruption of the grain collection plan and for malicious sabotage, organized by kulak and counterrevolutionary elements: . . .

The following measures should be undertaken with respect to these villages:

Immediate cessation of delivery of goods, complete suspension of cooperative and state trade in the villages, and removal of all available goods from cooperative and state stores.

Full prohibition of collective farm trade for both collective farms and collective farmers, and for private farmers.

Cessation of any sort of credit and demand for early repayment of credit and other financial obligations.

Investigation and purge of all sorts of foreign and hostile elements from cooperative and state institutions, to be carried out by organs of the Workers and Peasants Inspectorate.

Investigation and purge of collective farms in these villages, with removal of counterrevolutionary elements and organizers of grain collection disruption.

The Council of People’s Commissars and the Central Committee call upon all collective and private farmers who are honest and dedicated to Soviet rule to organize all their efforts for a merciless struggle against kulaks and their accomplices in order to: defeat in their villages the kulak sabotage of grain collection; fulfill honestly and conscientiously their grain collection obligations to the Soviet authorities; and strengthen collective farms.

—Addendum to the minutes of Politburo [meeting] No. 93, December 6, 1932

- What are the kulaks accused of?

- What punishment is being assessed on them?

Stalin speeded the drive to collectivization, and local officials did what they could to comply with the new targets for grain collection. By 1939, more than 90 percent of the peasants had been forced to live and work on collective farms. If they resisted, they could be arrested, and many were sent to labor camps in Siberia. While some poor peasants complied with collectivization because they had little of their own property to lose, middle-class peasants continued to oppose it, even killing their livestock rather than turning flocks over to the Soviet government. More than half the nation’s livestock was lost under collectivization in the 1930s, and the numbers did not recover until the 1950s. In some areas, spring planting did not occur due to the upheaval.

The failures of collectivization spelled deaths for millions in the Soviet Union. Approximately two million died resisting or in prison, and between five and ten million additional lives were lost in a famine caused by the chaos of the process, the peasants’ choice to slaughter their livestock, and government policies that took food from the peasants. The grain-producing region of Ukraine was hit especially hard; government decisions there caused mass starvation. Some officials actually went into homes and took whatever food they could find.

Approximately 3.9 million Ukrainians are estimated to have died in the famine they called the Holodomor (“death by famine” in Ukrainian).

The problems surrounding collectivization also led many within the Communist Party to question the wisdom of Stalin’s decisions. In 1934, the assassination of Sergei Kirov, a high-ranking Soviet politician, led to an investigation that uncovered what Stalin believed was a plot to kill him. Kirov’s death, together with the unrest caused by collectivization, the anti-Soviet rhetoric of Germany’s Nazi Party (which had taken control of Germany in 1933), and his knowledge that many Soviet politicians did not share his vision of the USSR’s future, fed Stalin’s growing feelings of paranoia. His belief that he was surrounded by enemies led to a reign of terror in which the Soviet secret police arrested millions of Soviet citizens on suspicion of disloyalty. Many were sent to prison camps in Siberia where they perished as a result of starvation and overwork. Some were executed immediately following brief trials. Some did not even receive trials. Among those imprisoned or killed were kulaks, former tsarist officials, intellectuals, Russian Orthodox priests, ethnic minorities, workers (labeled “saboteurs”) in factories where accidents had occurred under the frantic pace of the Five-Year Plan, Red Army officers, government officials, prominent Soviet politicians, and supporters of Lenin from the earliest days of the Bolshevik Revolution. Historians disagree about how many Soviets died as a result of the political purges of the 1930s, but one million is a likely figure.

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

Check out this repository of Soviet posters (opens in new tab) from the 1920s and 1930s.

Engineers of Human Souls

Despite the clear problems with Stalinist rule, many people living in the Soviet Union, about 80 percent of whom were peasants, were still optimistic about the promised equality they believed communism could bring to their lives. The school of socialist realism that dominated art in the Soviet Union glorified peasants and industrial workers, depicting heroic, muscular steelworkers and smiling farmers wielding agricultural implements. Paintings and drawings of male and female workers in the 1930s were about patriotism as much as artistic expression.

The reality behind the government’s rhetoric about building a worker’s paradise often fell short, however. Some improvements in the quality of life were made, literacy increased, electricity was brought to rural areas, and some people found opportunities for advancement not possible under tsarist rule. But not everyone shared in these changes. People whose innovations in the workplace increased production were rewarded with higher pay, recognition, and promotions, but the production goals party leaders laid out were often impossible to meet.

Urban life grew more difficult during the 1930s. Peasants migrated to the cities to fill jobs in the new factories built to speed industrialization. Hours were long, pay was low, and housing, clothing, and food were in short supply. People crowded into small apartments, and because it was hard to find enough to eat in the state-run stores, they became more dependent on dining halls at work or school, where it was also easier for officials to monitor their conversations. At the same time, many Soviet citizens remained excited by their belief that the government would repay their efforts by providing for their needs better than the tsarist government ever would have done.

Religion served to divide the Soviet government and the masses of Soviet people. Lenin had always seen it as dangerous and a competitor to socialism, so from the early days of the Soviet Union, religion was targeted by Communist leaders. Yet the history of Orthodox Christianity among the Russian people was long, and many found it difficult to abandon their faith and traditions despite government policies to discourage them.

Soviet ideology demanded that women play new roles in society and the economy, so millions took industrial or agricultural jobs outside the home through the 1920s and 1930s. Their situation was fraught with discrimination and emotional turmoil, however. Women were rarely given positions of power in their workplaces (or within the Soviet political hierarchy), yet they were expected to produce just as much as men. Nor did the role of homemaker and mother go away. Women had to fulfill both kinds of roles, highlighting the disparity between female and male work.

Lenin’s policy that introduced some aspects of capitalism in response to hardships and growing discontent among the Russian people

domestic plans adopted by the Soviet Union in the 1930s to target industrial and agricultural output goals that were usually unrealistic

the taking over of agriculture by a national government

an artistic movement in the Soviet Union that took the worker as a subject and was about patriotism as much as art