Chapter 11.1 A Global Economy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how trade agreements and attempts to regulate world trade have shaped the global economy since the 1990s

- Analyze the way multinational corporations have affected politics, workers, and the environment in developing nations

- Discuss globalization in the West and how it has affected workers around the world

In many ways, World Wars I and II were only temporary interruptions in a centuries-long process of global integration. This process is often called globalization, the interconnectedness of societies and economies throughout the world as a result of trade, technology, and the adoption and sharing of elements of culture. Globalization facilitates the movement of goods, people, technologies, and ideas across international borders. Historians of globalization note that it has a very long history. With the European colonization of the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and British colonization of Australia, all of the world’s inhabited continents became enmeshed in exchanges of peoples, products, and ideas that increased in the nineteenth century as the result of both technological developments and the imperialist impulses of industrialized nations. Only the world wars of the twentieth century brought a temporary halt to these exchanges. Furthermore, once the world wars were over, globalization not only resumed its pre–World War I trajectory but even gained speed, despite the Cold War and decolonization efforts in Asia and Africa. As the Cold War came to a close, the United States, Europe, and increasingly powerful corporations ensured that capitalism and free-market economics would dominate the globe.

Global Trade

Even during the Cold War and decolonization, economic development and industrialization continued around the world. Japan and West Germany, destroyed and defeated in the 1940s, were striking examples. Each dove headlong into postwar rebuilding efforts that paid huge dividends. They invested heavily in their economies and saw industrial production and economic growth skyrocket over the 1950s and 1960s. By 1970, both had become economic powerhouses in their regions.

Similar, but smaller, economic miracles occurred in other places, especially in Europe. Spain underwent a period of spectacular growth fueled by imported technology, government funding, and increased tourism and industrialization in the 1960s. Italy began even earlier. By the early 1960s, its annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth—the increase in value of all the goods and services the country was producing—had peaked at just over 8 percent. France bounced back from the war years with a rise in population and an impressive new consumer culture that became accustomed to a high standard of living and access to modern conveniences like automobiles, televisions, and household appliances. Comparable growth occurred in Belgium, Greece, and the Netherlands.

Contributing to this postwar economic growth was the emergence of regional economic cooperation in Western Europe. The process began with the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951. The original member countries of the ECSC were West Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. To both foster economic integration and preserve the peace, these member states agreed to break down trade barriers between them by creating a common market in steel and coal. Across the six countries, these products were allowed to flow without restrictions, like customs duties.

The success of the ECSC eventually paved the way for further economic integration in Europe with the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC), also called the Common Market, in 1957. The EEC used the economic-cooperation model developed by the ECSC and greatly expanded it to remove trading and investment restrictions across its member states, far beyond just coal and steel. While generally successful, the EEC’s efforts at economic integration occasionally met resistance. Farmers who stood to lose economically protested the way it opened national markets to agricultural products produced more cheaply in other countries and sought protectionist policies. Yet despite these protests and concerns, the EEC continued to expand.

Although Britain supported the EEC’s economic goals, it was initially not interested in the political cooperation the group represented. When it did signal its desire to join, Britain wanted special protections for its agriculture and other exceptions for its Commonwealth connections, such as Canada. This meant negotiating with France, then the EEC’s most powerful member. Since decisions at that time were made unanimously and member countries had the power to unilaterally veto, France’s approval was crucial. President Charles de Gaulle of France did not approve, however, and he cut off negotiations with Britain in 1960. Over the next several years, Britain officially applied for EEC membership twice: in 1961 and again in 1967. Both times de Gaulle worried that admitting Britain, with its strong ties to the United States, would transform the organization into an Atlantic community controlled by Washington. Britain was admitted in 1973 (along with Denmark and Ireland), when de Gaulle was no longer president of France. But many in the United Kingdom had wanted to stay out, especially those in the Conservative Party. It took a UK referendum in 1975 to confirm the country’s EEC membership.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Charles de Gaulle Vetoes British Admission to the EEC

In January 1963, French president Charles de Gaulle made the following statement at a press conference explaining his opposition to Britain’s application to join the EEC or Common Market:

England in effect is insular, she is maritime, she is linked through her exchanges, her markets, her supply lines to the most diverse and often the most distant countries; she pursues essentially industrial and commercial activities, and only slight agricultural ones. She has in all her doings very marked and very original habits and traditions. [. . .]One might sometimes have believed that our English friends, in posing their candidature to the Common Market, were agreeing to transform themselves to the point of applying all the conditions which are accepted and practised by the Six [the six founding members: Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany]. But the question, to know whether Great Britain can now place herself like the Continent and with it inside a tariff which is genuinely common, to renounce all Commonwealth preferences, to cease any pretence that her agriculture be privileged, and, more than that, to treat her engagements with other countries of the free trade area as null and void—that question is the whole question. [. . .]Further, this community, increasing in such fashion, would see itself faced with problems of economic relations with all kinds of other States, and first with the United States. It is to be foreseen that the cohesion of its members, who would be very numerous and diverse, would not endure for long, and that ultimately it would appear as a colossal Atlantic community under American dependence and direction, and which would quickly have absorbed the community of Europe. It is a hypothesis which in the eyes of some can be perfectly justified, but it is not at all what France is doing or wanted to do—and which is a properly European construction. Yet it is possible that one day England might manage to transform herself sufficiently to become part of the European community, without restriction, without reserve and preference for anything whatsoever; and in this case the Six would open the door to her and France would raise no obstacle, although obviously England’s simple participation in the community would considerably change its nature and its volume.

—Charles de Gaulle, Veto on British Membership of the EEC

- Why does de Gaulle note that Britain’s relationship with the United States is a problem?

- What does this statement suggest about the special protections Britain wanted in order to become an EEC member?

- Do you think that de Gaulle was right to worry about the influence of the United States? Why or why not?

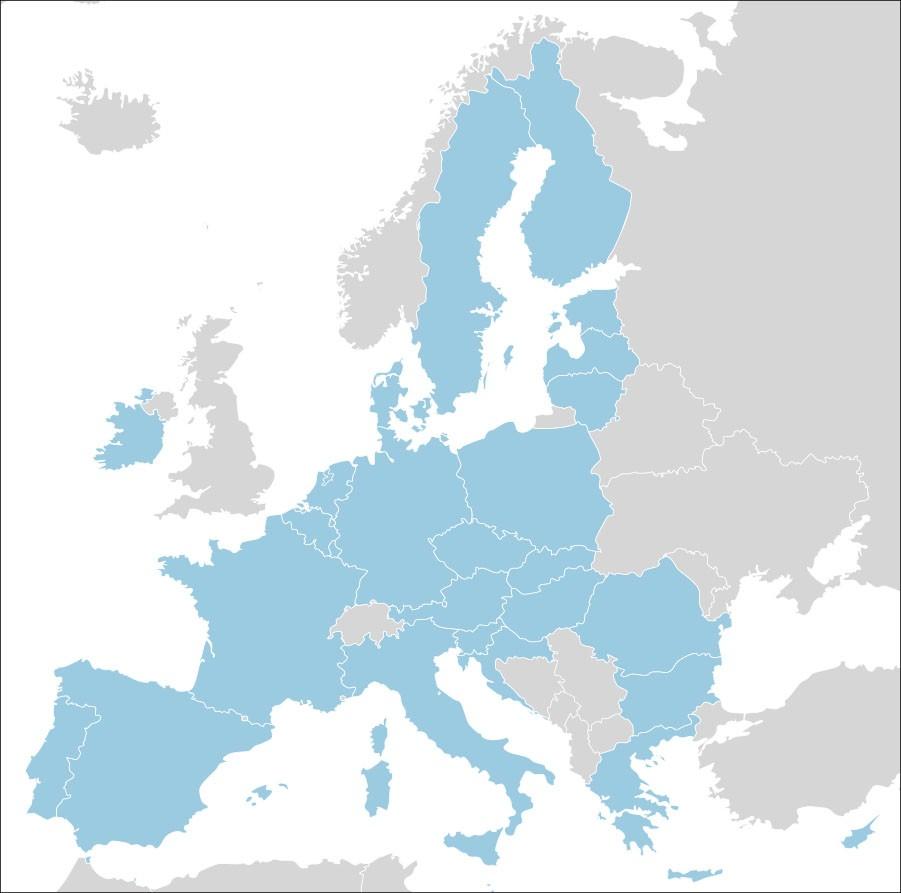

By 1993, the EEC had been integrated into the newly created European Union (EU), which had grown to fifteen member states by 1995 and in 2022 included twenty-seven member states (Figure 11.3). The EU was conceived as a single market for the free movement of goods, services, money, and people. Citizens of member countries can freely move to other EU countries and legally work there, just as they can in their own country. In 1999, the EU introduced its own currency, the euro. Initially used only for commercial and financial transactions in eleven of the EU countries, euro notes and coins had become the legal currency in the majority of EU countries by the start of 2002. The euro was not universally adopted by member states, though. The United Kingdom, Denmark, Sweden, and a few others kept their own currencies. The adoption of the euro was swiftly followed by a major expansion of the EU to include several Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

FIGURE 11.3 The European Union. From the six founding states (Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) that signed the Treaty of Paris in the early 1950s, the European Union has grown to include twenty-seven member states in 2022. (credit: modification of work “European Union map” by “Ssolbergj”/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

In 2016, however, 52 percent of the citizens of the United Kingdom voted to leave the EU, and Britain officially cut its ties with the organization, its largest trading partner, on January 31, 2020. Some EU opponents in the United Kingdom had claimed the group was economically dysfunctional, especially after the recession of 2008, and that it reduced British sovereignty. Many also disliked the fact that its membership in the EU made it easier for people from elsewhere in Europe, including recent immigrants from the Middle East and Africa, to enter Britain. Those who wanted to stay argued that leaving would hurt British trade with Europe and make Britain poorer. Some also argued that losing the trade advantages that came with belonging to the EU could result in shortages in stores and more expensive products.

The breakup, colloquially known as “Brexit,” was hardly amicable. In Britain, many who supported staying in the EU were shocked by the decision and demanded a re-vote, though none was taken. In Europe, the European Parliament, the EU’s legislative body, was angry that Brexit might threaten the entire EU project. To show its displeasure and possibly to deter any other member states from leaving, the European Parliament wanted the separation to be as painful for the United Kingdom as possible, and many member countries supported this hardline stance. In today’s post-Brexit world, there are new regulations on British goods entering the EU and no automatic recognition of British professional licenses in the EU. Britons seeking to make long-term stays in EU countries now must apply for visas.

Among the forces driving European economic integration was a desire for Europe to be more independent of the United States. This wish was understandable given the massive economic and political power the United States began wielding after World War II. Not only did the United States possess a huge military force with a global reach and growing installations in Europe and beyond, but its economic strength was the envy of the world. Having experienced the Great Depression in the years before the war, the United States emerged after it as an economic powerhouse with a highly developed industrial sector. More importantly, with the exception of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it had avoided the wartime destruction experienced in Europe and Asia. As a result, not only was it able to provide funds to war-torn nations to rebuild their economies and their infrastructure as part of the Marshall Plan, but U.S.-manufactured goods also flooded into markets around the world. By 1960,

U.S. GDP had grown to $543 billion a year (in current dollars). By comparison, the United Kingdom had the second-largest economy with a GDP of $73 billion (in current dollars).

The economic might of the United States brought unprecedented growth and a rise in the population’s standard of living in the decades after the war. With ready access to well-paying industrial jobs, the middle class boomed in the 1950s and 1960s. Their buying having been restrained during the war years because of the rationing of goods, consumers were eager to use their wartime savings to purchase new automobiles, televisions, household appliances, and suburban homes. Many enjoyed steady employment with new union-won benefits like weekends off and paid vacations. They also began sending their children to college in ever-greater numbers. By 1960, about 3.6 million young students were enrolled in higher education, an increase of 140 percent over the previous two decades. For many, access to higher education was the gateway to the middle or upper class.

By the 1970s, the U.S. economy began to cool, partially because of domestic inflation and increased competition from abroad. Oil embargoes by Arab nations belonging to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), in retaliation for U.S. support of Israel during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, and a general strategy by oil-producing nations to raise their prices, further stressed the economy by creating gas shortages for consumers. Other countries that had supported Israel, such as the Netherlands, also suffered from the embargo. Once dominant in most major industrial sectors, including the production of steel and automobiles, around the world, by the end of the 1970s, U.S. manufacturers were suffering as a result of competition from Japan and Western Europe. This reality led to a number of difficult economic transformations in the United States. But it also encouraged some national leaders to seek regional international economic integration along lines similar to Western Europe’s achievement. Beginning in the 1980s, the United States and Canada entered into negotiations to create their own regional free-trading zone. This made sense because Canada not only shared a long border with the United States but was also its largest trading partner. In 1988, the two countries agreed to the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (Canada-US FTA), which eliminated barriers to the movement of goods and services between the two.

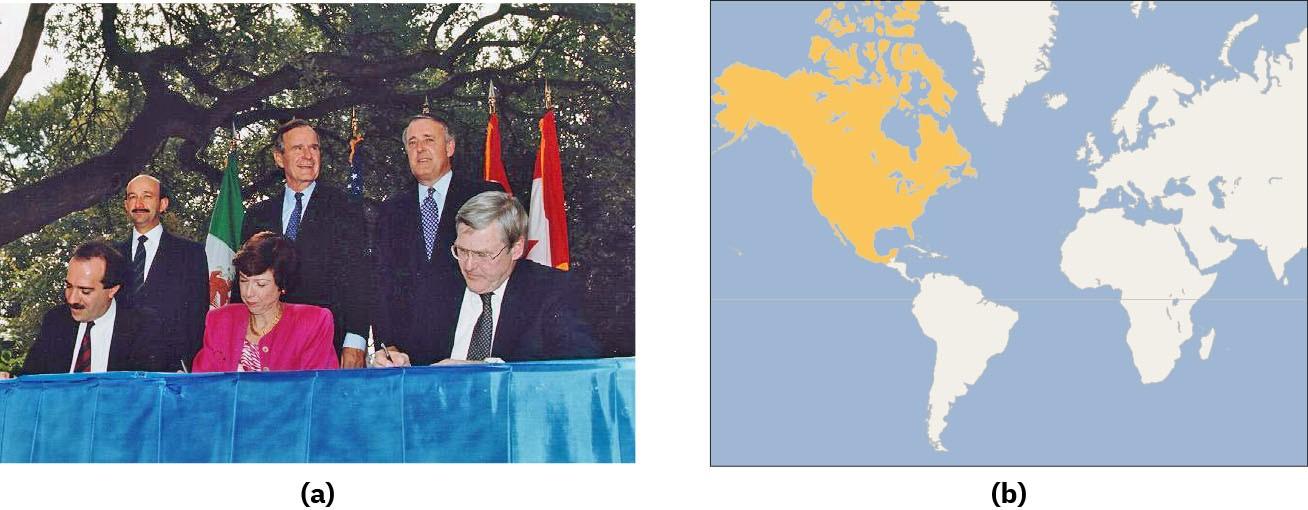

Almost immediately, Mexico signaled its interest in creating a similar free trade agreement with the United States. U.S. president Ronald Reagan had floated the concept during his 1980 election campaign. But successful completion of the Canada-US FTA convinced Mexican leaders that the time was ripe to act on the idea. Ultimately, Canada joined the plan with Mexico as well, and by the end of 1992, all three countries had signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (Figure 11.4). The intent of NAFTA was to reduce trade barriers and allow goods to flow freely among the three countries. Despite considerable resistance within the United States, largely from industrial workers who feared their factories and jobs would be relocated to Mexico where wages were far lower, the agreement was ratified by all three countries and went into effect in 1994.

The creation of Canada-US FTA and later NAFTA represented an important policy shift for the United States. Until the early 1980s, the country had largely avoided limited regional trading deals, preferring instead to seek comprehensive global agreements. Such efforts had begun relatively soon after World War II in the form of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947 by twenty-three countries. Initially conceived as a way to reinforce other postwar economic recovery efforts, GATT was designed to prevent the reemergence of prewar-style trade barriers, to lower trade barriers overall, and to create a system for arbitrating international trade disputes. Since its initial acceptance in 1947, GATT has undergone a number of revisions, completed in sessions referred to as rounds, to promote free trade and international investments.

In 1995, at the Uruguay Round, GATT transformed itself into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and cleared the path for free trade among 123 countries. Like GATT, the intent of the WTO was to support international trade, reduce trade barriers, and resolve trade disputes between countries. Unlike GATT, however, the WTO is not a free trade agreement. Rather, it is an organization that ensures nondiscriminatory trade between WTO countries. This means that trade barriers are allowed, but they must apply equally to all members. Many observers saw the creation of the WTO as a triumph of globalization, or the emergence of a single integrated global economy. Because the WTO is regarded as a major force for globalization, its meetings often attract protestors who oppose corporate power and the economic, political, and cultural influence of wealthy nations in the developed world on less-developed nations. In 1999, in Seattle, Washington, a diverse group of students, labor union representatives, environmentalists, and activists of many kinds protested the abuses associated with globalization. Police confronted activists staging marches and sit-ins with rubber bullets and tear gas, and trade talks ground to a halt. Meetings of the WTO continue to attract protestors.

As the creation of the EU and NAFTA demonstrate, the signing of international trade agreements like GATT, which was ratified by countries on six continents, did not prevent regions from establishing their own free trade blocs like MERCOSUR, the South American trading bloc created in 1991.

The West has also entered trade agreements with Asian countries. APEC, launched in 1989, was in many ways a response to the growth of regional trading blocs like ASEAN and the EEC. Initially composed of twelve Asia-Pacific countries, including Australia, the United States, South Korea, and Singapore, it has since grown to include Mexico, China, Chile, Russia, and more. It promotes free trade and international economic cooperation among its members.

Multinationals and the Push to Privatize

The growing global economic integration represented by the rise of the WTO and regional trading blocs opened new opportunities for multinational corporations to extend their reach and influence around the world. A multinational corporation, or MNC, is a corporate business entity that controls the production of goods and services in multiple countries. MNCs are not new. Some, like the British East India Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, exerted great influence during Europe’s imperial expansion in the early modern and modern periods. But with globalization and improvements in transportation and communication technology, MNCs have thrived, especially since the 1950s. They have used their growing wealth to lobby governments to create conditions favorable to their operation, enabling them to become even more powerful.

Multinationals have also benefited greatly from the lowering of trading barriers around the world. These developments have encouraged major automobile manufacturers like Volkswagen, and Chevrolet to build and operate assembly plants in Mexico, for example, where workers are paid lower wages than they are in countries like Germany or the United States. This translates to significant cost savings and thus higher profits for them. And because Mexico is part of a free trade bloc with the United States and Canada, cars made there can be exported for sale in the United States or Canada without the need to pay tariffs. Supporters of MNCs claim that the benefits for workers in this arrangement are also substantial. They get access to well-paying and reliable industrial jobs not available before, and their paychecks flow into the local community and contribute to a general rise in the standard of living. The companies themselves invest in local infrastructure like roads, powerlines, and factories, and their presence often helps expand support industries like restaurants that cater to workers and shipping companies that employ them to move their goods.

Technology spillovers also occur when MNCs either help to develop necessary job skills in local workers or introduce new technologies that ultimately become available to domestic industries in the host country.

Finally, MNCs that focus on retail and establish branches in other countries, such as Walmart, Aldi, Costco, Carrefour, Ikea, and many more, provide access to high-quality consumer goods like clothing, appliances, and electronics at competitive prices, raising the standard of living in the countries where they operate (Figure 11.5).

There are drawbacks, however. Critics of MNCs note that while workers may be paid more than they could earn working for local businesses, they are still paid far less than the multinational can afford. Workers are often prevented from forming unions and forced to work long hours in unsafe environments. Furthermore, many multinationals are based in developed countries, mostly in the West, and they tend to express the interests and cultural norms of those countries. This bias has sometimes led to accusations of neocolonialism (the use of economic, political, or cultural power by developed countries to influence or control less-developed countries), particularly for the way MNCs have helped accelerate the homogenization of cultures around the world by exporting not only goods from the West but also ideas and behaviors.

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

These short Planet Money videos follow the manufacture of a simple t-shirt (opens in new tab) and reveal how many people around the world are involved. Click on “Chapters” to navigate among the five short videos.

One such idea is that countries should encourage the privatization of public services like utilities, transportation systems, and postal services. Privatization means delegating these services to mostly private companies that operate to earn a profit rather than such services being delivered by arms of the government. Organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have pushed for privatization as a way to make these public services more efficient. The World Bank is an international organization that offers financing and support to developing countries seeking to improve their economies. Founded in 1944 to rebuild countries after World War II, it later shifted its focus to global development. The IMF, also created in 1944, promotes global monetary stability by helping countries improve their economies with fiscal plans and sometimes loans. In exchange, it requires countries to adopt plans that often include privatizing public services and paying off their debts.

In some places, this privatization process has been successful. The World Bank made efforts to privatize industries across Latin America. Some view privatization there as largely successful, noting that as the number of state-owned industries declined, the profitability and efficiency of the privatized companies increased. But sometimes, as in Bolivia, privatization came at considerable cost. In 1999, the Bechtel Corporation, a U.S.-based multinational, was awarded a contract by the Bolivian city of Cochabamba to improve the efficiency of the city’s water delivery system. By January 2000, however, water delivery in Cochabamba had actually become worse. Service rates increased even for people who did not receive any water at all. This result led to large and sometimes violent protests later known as the Cochabamba Water War. The Bolivian government sided with the protestors, expelled Bechtel, and passed the Bolivian Water Law in April 2000. Water in Bolivia was no longer privatized. In the aftermath of the protests, which drew international media attention, the World Bank promised to study and revise its procedures and recommendations.

Exporting Culture

Besides promoting controversial ideas like privatization, MNCs, many of which are headquartered in the United States, also are responsible for exporting elements of western culture, especially popular culture. Although many people around the world enjoy such things as western fashions, movies and television shows, popular music, and fast food, other people fear that such influences harm local cultures and contribute to the Americanization (and homogenization) of the world.

Few countries have been as culturally influential as the United States, thanks to its global dominance after World War II. U.S. troops at military bases around the world were often the first to expose their hosts in Europe and Asia to American traditions, sports, and norms. Consumers around the world purchased a wide range of “Made in USA” products, including Coca-Cola, Levi’s jeans, and Hollywood movies, which, along with American music, helped to spread the American dialect of the English language.

Some early Americanization efforts were intentional, such as in Germany and Japan where the goal was to lay a foundation for U.S.-style democracy by projecting ideas like freedom and affluence via popular culture. These ideas were also attractive in South Korea and South Vietnam. Typically, young people patronized fast-food restaurants like McDonald’s and Pizza Hut, purchased blue jeans and T-shirts, watched American television shows, and sought out recordings of the latest popular music.

The popularity of American culture led many countries to fear the loss of their own unique cultural characteristics and the weakening of their domestic industries. Brazil, Greece, Spain, South Korea, and others imposed screen quotas, limiting the hours theaters could show foreign movies. In 1993, France forced the nation’s radio stations to allocate 40 percent of their airtime to exclusively French music.

Winners and Losers in a Globalizing World

While it is tempting to see globalization and the rise of MNCs as generally benefiting the people of developed countries, the reality is more complex. Improvements in transportation and MNCs’ use of labor resources in countries around the world have sometimes harmed workers in developed countries like the United States. Supporters of NAFTA, for example, argued that the United States would benefit from reduced trade barriers, lower prices for agricultural goods from Mexico, and newly available jobs for lower-wage workers. Opponents, however, recognized that the groups hardest hit by transformations in the labor market would be those least able to withstand the damage, mainly working-class manufacturing workers in the United States and Canada. Both sets of predictions proved accurate.

After NAFTA was implemented in 1994, trade and development across the three participating countries surged. Trade across the U.S.-Mexico border surpassed $480 billion by 2015, an inflation-adjusted increase of 465 percent over the pre-NAFTA total. A similar, if smaller, increase occurred in U.S.-Canadian trade during the same time. In Mexico, per capita GDP grew by more than 24 percent, topping $9,500. Even more impressive growth occurred in Canada and the United States.

But between 1993 and 2021, the United States lost nearly eighteen million manufacturing jobs when some companies found it more profitable to relocate to Mexico. Not all these job losses can be attributed to NAFTA, but many can, as manufacturing that otherwise would have taken place in the United States was moved to maquiladoras, factories in Mexico along the U.S. border that employ people for low wages. Maquiladoras often receive materials from U.S. manufacturers, transform them into finished products, and then ship them back to the United States for the manufacturers to use. After the passage of NAFTA, U.S. car manufacturers began to make use of parts produced inexpensively in Mexico that would have been much more expensive had they been produced in the United States. For example, in 2015, Brake Parts Inc. moved its operations from California to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, and almost three hundred U.S. workers lost their jobs in the process.

Workers in the automobile industry, once the backbone of the U.S. industrial sector, suffered as jobs and automotive plants were relocated to Mexico. Some economists, however, argue that the use of inexpensive parts produced in maquiladoras allowed the U.S. automobile industry to survive. Jobs in the clothing industry also declined 85 percent. There were simply fewer obvious advantages to keeping such jobs in the United States.

Economists say the loss of manufacturing jobs was less a result of NAFTA than of other structural economic changes in the United States, such as automation. And while many U.S. workers lost their jobs as a result of NAFTA, millions of others found work in industries that produced goods for sale in Mexico. Nevertheless, the impression that NAFTA and globalization have brought poverty and misery to the working class in the United States remains strong and has influenced the nation’s politics since the 1990s. Responding to these beliefs, in 2017, President Donald Trump instigated a renegotiation of NAFTA, creating the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The USMCA included strong property rights protections, compelled Canada to open its dairy market more broadly, and required that workers in the automotive sector in all three countries be paid competitive wages. The agreement replaced NAFTA and went into effect in 2020.

The complaints that arose during the NAFTA debates had been voiced for decades. Since the 1970s, many in the United States had argued that globalization allowed Japan, its enemy during World War II, to race ahead and outcompete domestic manufacturers. By the 1980s, Japan was exporting a huge volume of consumer electronics and automobiles into the U.S. market. Its economic resurgence created a massive trade deficit (the difference in value between what a country imports and what it exports) in the United States and rising concerns about its global competitiveness.

Political figures like Walter Mondale, the 1984 Democratic Party nominee for president, called the trade deficit a threat to the United States and spoke in dire terms about an emerging global trade war. Many others drew connections between Japan’s economic rise and growing unemployment in the United States. Auto workers were especially vocal, declaring that Japan was using unfair practices and artificially limiting the number of American cars that could be sold in Japan (Figure 11.7). While the reality was more complicated, politicians were primed to respond with tough talk and reforms. In 1981, President Reagan pressured Japan to limit the number of cars it exported to the United States. The United States also made efforts to limit the importation of foreign steel and semiconductors for the same reasons.

By the start of the 1990s, Japan’s economic engine was starting to cool, and so were American concerns about Japanese dominance. However, companies in the developed world faced challenges rooted in the high cost of living and resulting high wages they had to pay to their employees. Globalization offered a solution in the form of outsourcing and offshoring. Outsourcing occurs when a company hires an outside firm, sometimes abroad, to perform tasks it used to perform internally, like accounting, payroll, human resources, and data processing services. Offshoring occurs when a company continues to conduct its own operations but physically moves them overseas to access cheaper labor markets. Outsourcing and offshoring were hardly new in the 1990s. But with globalization, trade agreements like NAFTA, and the ability to ship goods around the world, they became a major cost-savings option for large companies. Trade agreements like NAFTA made it possible to build plants in Mexico and still sell the products they produced in the United States. Companies could also offshore some of their operations to countries in Asia where labor was much cheaper.

Those hired overseas experienced their own problems, however, because outsourcing often led to the rise of sweatshops, factories where poorly paid workers labor in dangerous environments. Images of women and children in horrific working conditions in Central America, India, and Southeast Asia circulated around the developed world in the 1990s as examples of the consequences of outsourcing. Major MNCs like Nike, Gap, Forever 21, Walmart, Victoria’s Secret, and others have been harshly criticized for using sweatshops to produce their shoes and clothing lines. In 2013, the plight of sweatshop workers gained widespread attention when a building called Rana Plaza, a large complex of garment factories in Bangladesh, collapsed, killing 1,134 and injuring another 2,500 of the low-wage workers who made clothing for luxury brands like Gucci, Versace, and Moncler. The disaster led to a massive protest in Bangladesh demanding better wages and reforms. In the aftermath, studies and inspections of similar factories revealed that almost none had adequate safety infrastructure in place.

THE PAST MEETS THE PRESENT

Sweatshops and Factory Safety: Then and Now

On March 25, 1911, a fire started at the Triangle shirtwaist factory in New York City that caused the deaths of 146 workers, most of them immigrant women and girls of Italian or Jewish heritage. It was soon discovered that the factory had poor safety features, and the doors were locked during the workday, making it impossible for the workers to flee.

News of the tragedy spread quickly in New York and around the country. Government corruption, which was widely reported, had allowed the factory to continue operating despite its poor conditions and safety deficiencies. In the end, the tragedy led to massive protests in New York. The city even set up a Factory Investigating Commission to prevent such events from happening again.

Just over a century later in Bangladesh, a similar tragedy occurred. On April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,134 workers and injuring thousands of others. The owners of the garment factories housed in the building knew it had structural problems but still demanded that employees continue to work or lose their jobs.

A massive public outcry in Bangladesh followed the building’s collapse. People were outraged by the disaster and by the fact that the workers made some of the lowest wages in the world sewing garments for major multinational companies. The public demanded that the families be compensated and those responsible be prosecuted, leading many of the garment companies to donate money to the families of those lost. The disaster also inspired a public movement to make the garment industry in Bangladesh more transparent.

- Why do you think it remains difficult to get garment factories like these to prioritize safety?

- Beyond the obvious, what are some of the similarities between the two tragedies?

LINK TO LEARNING

LINK TO LEARNING

To better understand the similarities between the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire and the Rana Plaza collapse, view photos of the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire (opens in new tab) and read interviews with survivors (opens in new tab) of the fire. Then look at the photo essay covering the Rana Plaza collapse (opens in new tab) by award-winning photographer and activist Taslima Akhter.

The multinational technology company Apple Inc. has faced intense criticism in recent years for its use of foreign-owned sweatshops in Asia. Since the early 2000s, reports of sprawling factories with hundreds of thousands of workers assembling iPhones have made the news and led to a public-relations nightmare for the company. Investigative journalists have revealed that workers suffer a pattern of harsh and humiliating punishments, fines, physical assaults, and withheld wages. In some instances, conditions in the factories have pushed assembly-line workers to commit suicide rather than continue. Apple has insisted it takes all such accusations seriously and has tried to end relationships with such assembly plants, but those familiar with the problems have complained that little progress has been made.

Even when MNCs commit to providing a safe working environment and fair wages abroad, the practice of subcontracting often makes this impossible to guarantee. Foreign companies to whom multinationals send work often distribute it among a number of smaller companies that may also subcontract it, in turn. It is sometimes difficult for MNCs to know exactly where their goods are actually produced and thus to enforce rules about wages and working conditions.

Multinationals have harmed the countries in which they operate in other ways as well, including deforestation and the depletion of clean, drinkable water. They are also major producers of greenhouse gases and responsible for air pollution and the dumping of toxic waste. MNCs leave little in the way of profit in the countries they exploit, so funds are often lacking to repair or mitigate the damage they do.

The desire for a better life and opportunities in the developed world has led many in the developing world to migrate. Millions of immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Latin America have made their way into the United States over the last few decades. They typically find low-paid labor harvesting crops, cleaning homes, and serving as caretakers for children. In these jobs, they serve an important role in the U.S. economy, often doing work domestic workers are unwilling to do. Many entered the country illegally and live and work in the shadows to avoid deportation. This makes them vulnerable to abuse, and they are sometimes preyed on by human traffickers and unscrupulous employers. The United States is not the only country where this dynamic occurs. Saudi Arabia, for example, depends heavily on foreign workers to fill jobs Saudi Arabian citizens are reluctant to take, such as caretaker or domestic servant. Some workers have reported physical and emotional abuse to international human rights watchdog organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Being immigrants, they often have little access to relief from the country’s justice system.

the interconnectedness of societies and economies throughout the world as a result of trade, technology, and adoption and sharing of various aspects of culture

a single-market zone created in 1993 to allow the free movement of goods, services, money, and people among European member states

a 1992 trade agreement between the United States, Canada, and Mexico to reduce trade barriers and allow goods to flow freely

a 1947 trade agreement among twenty-three countries to reinforce postwar economic recovery, later replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO)

a corporate business entity that controls the production of goods and services in multiple countries

the process of hiring outside contractors, sometimes abroad, to perform tasks a company once performed internally

the process of moving some of a company’s operations overseas to access cheaper labor markets