15 Chapter 15: Music of the Romantic Era

Romantic Era Explored

Introduction

When people talk about “Classical” music, they usually mean Western art music of any time period. But the Classical period was actually a very short era, basically the second half of the 18th century. Only two Classical period composers are widely known: Mozart and Haydn.

The Romantic era produced many more composers whose names and music are still familiar and popular today: Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Schumann, Schubert, Chopin, and Wagner are perhaps the most well known, but there are plenty of others who may also be familiar, including Strauss, Verdi, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Puccini, and Mahler. Ludwig van Beethoven, possibly the most famous composer of all, is harder to place. His early works are from the Classical period and are clearly Classical in style. But his later music, including the majority of his most famous music, is just as clearly Romantic.

The term Romantic covers most of the music (and art and literature) of Western civilization from the 19th century (the 1800s). But there has been plenty of music written in the Romantic style in the 20th century (including many popular movie scores), and music isn’t considered Romantic just because it was written in the 19th century. The beginning of that century found plenty of composers (Rossini, for example) who were still writing Classical sounding music. And by the end of the century, composers were turning away from Romanticism and searching for new idioms, including post Romanticism, Impressionism, and early experiments in Modern music.

Background, Development, and Influence

Classical Roots

Sometimes a new style of music happens when composers forcefully reject the old style. Early Classical composers, for example, were determined to get away from what they considered the excesses of the Baroque style. Modern composers also were consciously trying to invent something new and very different.

But the composers of the Romantic era did not reject Classical music. In fact, they were consciously emulating the composers they considered to be the great classicists: Haydn, Mozart, and particularly Beethoven. They continued to write symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and operas, forms that were all popular with classical composers. They also kept the basic rules for these forms as well as keeping the rules of rhythm, melody, harmony, harmonic progression, tuning, and performance practice that were established in (or before) the Classical period.

The main difference between Classical and Romantic music came from attitudes toward these “rules.” In the 18th century, composers were primarily interested in forms, melodies, and harmonies that provided an easily audible structure for the music. In the first movement of a sonata, for example, each prescribed section would likely be where it belonged, of the appropriate length, and in the proper key. In the 19th century, the “rules” that provided this structure were more likely to be seen as boundaries and limits that needed to be explored, tested, and even defied. For example, the first movement of a Romantic sonata may contain all the expected sections as the music develops, but the composer might feel free to expand or contract some sections or to add unexpected interruptions between them. The harmonies in the movement might lead away from and back to the tonic just as expected, but they might wander much further afield than a Classical sonata would before making their final return.

Different Approaches to Romanticism

In fact, one could divide the main part of the Romantic era into two schools of composers. Some took a more conservative approach. Their music is clearly Romantic in style and feeling, but it also still clearly does not want to stray too far from the Classical rules. Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms are in this category.

Other composers felt more comfortable with pushing the boundaries of the acceptable. Berlioz, Strauss, and Wagner were all progressives whose music challenged the audiences of their day.

Where to Go after Romanticism?

Perhaps it was inevitable, after decades of pushing at all limits to see what was musically acceptable, that the Romantic era would leave later composers with the question of what to explore or challenge next. Perhaps because there was no clear answer to this question (or several possible answers), many things were happening in music by the end of the Romantic era.

The period that includes the final decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th is sometimes called the post Romantic era. This is the period when many composers, such as Jean Sibelius, Bela Bartok, and Ralph Vaughan-Williams, concentrated on the traditions of their own countries, producing strongly nationalistic music. Others, such as Mahler and Strauss, were taking Romantic musical techniques to their utmost reasonable limits. In France, Debussy and Ravel were composing pieces that some listeners felt were the musical equivalent of impressionistic paintings. Impressionism and some other -isms, such as Stravinsky’s primitivism, still had some basis in tonality; but others, such as serialism, rejected tonality and the Classical Romantic tradition completely, believing that it had produced all that it could. In the early 20th century, these Modernists eventually came to dominate the art music tradition. Though the sounds and ideals of Romanticism continued to inspire some composers, the Romantic period was essentially over by the beginning of the 20th century.

Historical Background

Music doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It is affected by other things that are going on in society; ideas, attitudes, discoveries, inventions, and historical events may affect the music of the times.

For example, the “Industrial Revolution” was gaining steam throughout the 19th century. This had a very practical effect on music: there were major improvements in the mechanical valves and keys that most woodwinds and brass instruments depend on. The new, improved instruments could be played more easily and reliably and often had a bigger, fuller, better tuned sound. Strings and keyboard instruments dominated the music of the Baroque and Classical periods, with small groups of winds added for color. As the 19th century progressed and wind instruments improved, more and more winds were added to the orchestra, and their parts became more and more difficult, interesting, and important. Improvements in the mechanics of the piano also helped it usurp the position of the harpsichord to become the instrument that to many people is the symbol of Romantic music.

Another social development that had an effect on music was the rise of the middle class. Classical composers lived on the patronage of the aristocracy; their audience was generally small, upper class, and knowledgeable about music. The Romantic composer, on the other hand, was often writing for public concerts and festivals, with large audiences of paying customers who had not necessarily had any music lessons. In fact, the 19th century saw the first “pop star”–type stage personalities. Performers like Paganini and Liszt were the Elvis Presleys of their day.

Romantic Music as an Idea

But perhaps the greatest effect that society can have on an art is in the realm of ideas.

The music of the Classical period reflected the artistic and intellectual ideals of its time. Form was important, providing order and boundaries. Music was seen as an abstract art, universal in its beauty and appeal, above the pettinesses and imperfections of everyday life. It reflected, in many ways, the attitudes of the educated and the aristocratic of the “Enlightenment” era. Classical music may sound happy or sad, but even the emotions stay within acceptable boundaries.

Romantic era composers kept the forms of Classical music, but the Romantic composer did not feel constrained by form. Breaking through boundaries was now an honorable goal shared by the scientist, the inventor, and the political liberator. Music was no longer universal; it was deeply personal and sometimes nationalistic. The personal sufferings and triumphs of the composer could be reflected in stormy music that might even place a higher value on emotion than on beauty. Music was not just happy or sad; it could be wildly joyous, terrified, despairing, or filled with deep longings.

It was also more acceptable for music to clearly be from a particular place. Audiences of many eras enjoyed an opera set in a distant country, complete with the composer’s version of exotic sounding music. But many 19th century composers (including Weber, Wagner, Verdi, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Grieg, Dvořák, Sibelius, and Albeniz) used folk tunes and other aspects of the musical traditions of their own countries to appeal to their public. Much of this nationalistic music was produced in the post Romantic period, in the late 19th century; in fact, the composers best known for folk inspired classical music in England (Holst and Vaughan Williams) and the U.S. (Ives, Copland, and Gershwin) were 20th century composers who composed in Romantic, post Romantic, or Neoclassical styles instead of embracing the more severe Modernist styles.

Music can also be specific by having a “program.” Program music is music that, without words, tells a story or describes a scene. Richard Strauss’s tone poems are perhaps the best known works in this category, but program music has remained popular with many composers through the 20th century. Again, unlike the abstract, universal music of the Classical composers, Romantic era program music tried to use music to describe or evoke specific places, people, and ideas. And again, with program music, those Classical rules became less important. The form of the music was chosen to fit with the program (the story or idea), and if it was necessary at some point to choose sticking more closely to the form or to the program, the program usually won.

As mentioned above, post Romantic composers felt ever freer to experiment and break the established rules for form, melody, and harmony. Many modern composers have, in fact, gone so far that the average listener again finds it difficult to follow. Romantic style music, on the other hand, with its emphasis on emotions and its balance of following and breaking the musical “rules,” still finds a wide audience.

Art Song

Art songs are not new to the Romantic era. Many composers of earlier historical periods composed songs that would fit the definition of art song as listed on this page. We study art songs now because they were such an integral part of the Romantic repertoire, particularly that of Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. Because so many art songs in a Romantic style were composed by German composers, we often use the German word for songs, “lieder,” when studying this genre.

Introduction

An art song is a vocal music composition, usually written for one voice with piano accompaniment, and usually in the classical tradition. By extension, the term “art song” is used to refer to the genre of such songs. An art song is most often a musical setting of an independent poem or text “intended for the concert repertory” “as part of a recital or other relatively formal social occasion.”

Art Song Characteristics

While many pieces of vocal music are easily recognized as art songs, others are more difficult to categorize. For example, a wordless vocalise written by a classical composer is sometimes considered an art song and sometimes not.

Other factors help define art songs:

- Songs that are part of a staged work (such as an opera or a musical) are not usually considered art songs. However, some Baroque arias that “appear with great frequency in recital performance” are now included in the art song repertoire.

- Songs with instruments besides piano and/or other singers are referred to as “vocal chamber music” and are usually not considered art songs.

- Songs originally written for voice and orchestra are called “orchestral songs” and are not usually considered art songs, unless their original version was for solo voice and piano.

- Folk songs are generally not considered art songs unless they are concert arrangements with piano accompaniment written by a specific composer. Several examples of these songs include Aaron Copland’s two volumes of Old American Songs, the Folksong arrangements by Benjamin Britten, and the Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Spanish Folksongs) by Manuel de Falla.

- There is no agreement regarding sacred songs. Many song settings of biblical or sacred texts were composed for the concert stage and not for religious services; these are widely known as art songs (for example, the Vierernste Gesange by Johannes Brahms). Other sacred songs may or may not be considered art songs.

- A group of art songs composed to be performed in a group to form a narrative or dramatic whole is called a song cycle.

Languages and Nationalities

Art songs have been composed in many languages and are known by several names. The German tradition of art song composition is perhaps the most prominent one; it is known as Lieder. In France, the term Melodie distinguishes art songs from other French vocal pieces referred to as chansons. The Spanish Cancian and the Italian Canzone refer to songs generally and not specifically to art songs.

Art Song Formal Design

The composer’s musical language and interpretation of the text often dictate the formal design of an art song. If all of the poem’s verses are sung to the same music, the song is strophic. Arrangements of folk songs are often strophic, and “there are exceptional cases in which the musical repetition provides dramatic irony for the changing text, or where an almost hypnotic monotony is desired.” Several of the songs in Schubert’s Die schone Mullerin are good examples of this. If the vocal melody remains the same but the accompaniment changes under it for each verse, the piece is called a “modified strophic” song.

In contrast, songs in which “each section of the text receives fresh music” are called through composed. Some through composed works have some repetition of musical material in them.

Many art songs use some version of the ABA form (also known as “song form”), with a beginning musical section, a contrasting middle section, and a return to the first section’s music.

Art Song Performance and Performers

Performance of art songs in recital requires some special skills for both the singer and pianist. The degree of intimacy “seldom equaled in other kinds of music” requires that the two performers “communicate to the audience the most subtle and evanescent emotions as expressed in the poem and music.” The two performers must agree on all aspects of the performance to create a unified partnership, making art song performance one of the “most sensitive type(s) of collaboration.”

Even though classical vocalists generally embark on successful performing careers as soloists by seeking out opera engagements, a number of today’s most prominent singers have built their careers primarily by singing art songs, including Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Thomas Quasthoff, Ian Bostridge, Matthias Goerne, Susan Graham, and Elly Ameling.

Pianists, too, have specialized in playing art songs with great singers. Gerald Moore, Graham Johnson, and Martin Katz are three such pianists who have specialized in accompanying art song performances.

Prominent Composers of Art Songs

British

- John Dowland

- Thomas Campion

- Hubert Parry

- Henry Purcell

- Frederick Delius

- Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Roger Quilter

- John Ireland

- Ivor Gurney

- Peter Warlock

- Michael Head

- Gerald Finzi

- Benjamin Britten

- Morfydd Llwyn Owen

- Michael Tippett

- Ian Venables

- Judith Weir

- George Butterworth

- Francis George Scott

American

- Amy Beach

- Arthur Farwell

- Charles Ives

- Charles Griffes

- Ernst Bacon

- John Jacob Niles

- John Woods Duke

- Ned Rorem

- Richard Faith

- Samuel Barber

- Aaron Copland

- Lee Hoiby

- William Bolcom

- Daron Hagen

- Richard Hundley

- Emma Lou Diemer

Austrian and German

- Joseph Haydn

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Franz Schubert

- Hugo Wolf

- Gustav Mahler

- Alban Berg

- Arnold Schoenberg

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold

- Viktor Ullmann

- Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Johann Carl Gottfried Loewe

- Fanny Mendelssohn

- Felix Mendelssohn

- Robert Schumann

- Clara Schumann

- Johannes Brahms

- Richard Strauss

- Hanns Eisler

- Kurt Weill

French

- Hector Berlioz

- Charles Gounod

- Pauline Viardot

- César Franck

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Georges Bizet

- Emmanuel Chabrier

- Henri Duparc

- Jules Massenet

- Gabriel Fauré

- Claude Debussy

- Erik Satie

- Albert Roussel

- Maurice Ravel

- Jules Massenet

- Darius Milhaud

- Reynaldo Hahn

- Francis Poulenc

- Olivier Messiaen

Spanish

19th Century Composers

- Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- Raman Carnicery Batlle

- Ruperto Chapa

- Antonio de la Cruz

- Manuel Fernandez Caballero

- Manuel Garcia

- Sebastian de Iradier

- Josa Lean

- Cristóbal Oudrid

- Antonio Reparaz

- Emilio Serrano y Ruiz

- Fernando Sor

- Joaquín Valverde

- Amadeo Vives

20th Century Composers

- Enrique Granados

- Manuel de Falla

- Joaquín Rodrigo

- Joaquín Turina

Italian

- Claudio Monteverdi

- Gioachino Rossini

- Gaetano Donizetti

- Vincenzo Bellini

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Amilcare Ponchielli

- Paolo Tosti

- Ottorino Respighi

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

- Luciano Berio

- Lorenzo Ferrero

Eastern European

- Franz Liszt—Hungary (nearly all his art song settings are of texts in non-Hungarian European languages, such as French and German)

- Antonín Dvořák—Bohemia

- Leoš Janáček—Bohemia (Czechoslovakia)

- Béla Bartók—Hungary

- Zoltán Kodály—Hungary

- Frédéric Chopin—Poland

- Stanisław Moniuszko—Poland

Nordic

- Edvard Grieg—Norway (set German as well as Norse and Danish poetry)

- Jean Sibelius—Finland (set both Finnish and Swedish)

- Yrjö Kilpinen—Finland

- Wilhelm Stenhammar—Sweden

- Hugo Alfvén—Sweden

- Carl Nielsen—Denmark

Russian

- Mikhail Glinka

- Alexander Borodin

- Caesar Cui

- Nikolai Medtner

- Modest Mussorgsky

- Petr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

- Alexander Glazunov

- Sergei Rachmaninoff

- Sergei Prokofiev

- Igor Stravinsky

- Dmitri Shostakovich

Ukrainian

- Vasyl Barvinsky

- Stanyslav Lyudkevych

- Mykola Lysenko

- Nestor Nyzhankivsky

- Ostap Nyzhankivsky

- Denys Sichynsky

- Myroslav Skoryk

- Ihor Sonevytsky

- Yakiv Stepovy

- Kyrylo Stetsenko

Other

Filipino

- Marco Cahulogan

- Carlo Roberto Quijano

- Nicanor Abelardo

- Juan dela Cruz

Afrikaans

- Jellmar Ponticha

- Stephanus Le Roux Marais

Franz Schubert

Schubert’s life seems to follow, tragically, the cliché of the Romantic artist: a suffering composer who languishes in obscurity, his genius only appreciated after his untimely death. While Schubert did enjoy the respect of a close circle of friends, his music was not widely received during his lifetime. Though we study him in our Romantic module, Schubert does not fit neatly into the Romantic period. Like Beethoven, Schubert is a transitional figure. Some of his music, particularly his earlier instrumental compositions, tends toward a more classical approach. However, the melodic and harmonic innovation in his art songs and later instrumental works sit more firmly in the Romantic tradition. Because his art songs are so clearly Romantic in their inception, and because art songs make up the majority of his compositions, we study him as part of the Romantic era.

Introduction

Franz Peter Schubert (31 January 1797–19 November 1828) was an Austrian composer.

Schubert died at 31 but was extremely prolific during his lifetime. His output consists of over six hundred secular vocal works (mainly Lieder), seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music, and a large body of chamber and piano music. Appreciation of his music while he was alive was limited to a relatively small circle of admirers in Vienna, but interest in his work increased significantly in the decades following his death. Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, and other 19th century composers discovered and championed his works. Today, Schubert is ranked among the greatest composers of the late Classical era and early Romantic era and is one of the most frequently performed composers of the early 19th century.

Music

Schubert was remarkably prolific, writing over 1,500 works in his short career. The largest number of these are songs for solo voice and piano (over 600). He also composed a considerable number of secular works for two or more voices—namely, part songs, choruses, and cantatas. He completed eight orchestral overtures and seven complete symphonies, in addition to fragments of six others. While he composed no concertos, he did write three concertante works for violin and orchestra. There is a large body of music for solo piano, including fourteen complete sonatas, numerous miscellaneous works and many short dances. There is also a relatively large set of works for piano duet. There are over fifty chamber works, including some fragmentary works. His sacred output includes seven masses, one oratorio and one requiem, among other mass movements and numerous smaller compositions. He completed only eleven of his twenty stage works.

Style and Reception

In July 1947, the 20th century composer Ernst Krenek discussed Schubert’s style, abashedly admitting that he had at first “shared the wide spread opinion that Schubert was a lucky inventor of pleasing tunes . . . lacking the dramatic power and searching intelligence which distinguished such ‘real’ masters as J. S. Bach or Beethoven.” Krenek wrote that he reached a completely different assessment after close study of Schubert’s pieces at the urging of friend and fellow composer Eduard Erdmann. Krenek pointed to the piano sonatas as giving “ample evidence that [Schubert] was much more than an easy going tune smith who did not know, and did not care, about the craft of composition.” Each sonata then in print, according to Krenek, exhibited “a great wealth of technical finesse” and revealed Schubert as “far from satisfied with pouring his charming ideas into conventional molds; on the contrary he was a thinking artist with a keen appetite for experimentation.”

That “appetite for experimentation” manifests itself repeatedly in Schubert’s output in a wide variety of forms and genres, including opera, liturgical music, chamber and solo piano music, and symphonic works. Perhaps most familiarly, his adventurousness manifests itself as a notably original sense of modulation, as in the second movement of the String Quintet (D 956), where he modulates from E major, through F minor, to reach the tonic key of E major. It also appears in unusual choices of instrumentation, as in the Sonata in A minor for arpeggione and piano (D 821), or the unconventional scoring of the Trout Quintet (D 667).

While he was clearly influenced by the Classical sonata forms of Beethoven and Mozart (his early works, among them notably the 5th Symphony, are particularly Mozart), his formal structures and his developments tend to give the impression more of melodic development than of harmonic drama. This combination of Classical form and long breathed Romantic melody sometimes lends them a discursive style: his Great C major Symphony was described by Robert Schumann as running to “heavenly lengths.” His harmonic innovations include movements in which the first section ends in the key of the subdominant rather than the dominant (as in the last movement of the Trout Quintet). Schubert’s practice here was a forerunner of the common Romantic technique of relaxing, rather than raising, tension in the middle of a movement, with final resolution postponed to the very end.

Listen: Sonata

Please listen to Sonata in A minor for arpeggione and piano, D 821, performed by Hans Goldstein (cello) and Clinton Adams (piano).

I. Allegro Moderato

II. Adagio and III. Allegretto

It was in the genre of the Lied, however, that Schubert made his most indelible mark. Leon Plantinga remarks, “In his more than six hundred Lieder he explored and expanded the potentialities of the genre as no composer before him.” Prior to Schubert’s influence, Lieder tended toward a strophic, syllabic treatment of text, evoking the folksong qualities engendered by the stirrings of Romantic nationalism. Among Schubert’s treatments of the poetry of Goethe, his settings of “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (D 118) and “Der Erlkönig” (D 328) are particularly striking for their dramatic content, forward looking uses of harmony, and use of eloquent pictorial keyboard figurations, such as the depiction of the spinning wheel and treadle in the piano in “Gretchen” and the furious and ceaseless gallop in “Erlkönig.” He composed music using the poems of a myriad of poets, with Goethe, Mayrhofer, and Schiller being the top three most frequent, and others like Heinrich Heine, Friedrich Rückert, and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, among many others. Also of particular note are his two song cycles on the poems of Wilhelm Müller, “Die schone Mullerin” and “Winterreise,” which helped to establish the genre and its potential for musical, poetic, and almost operatic dramatic narrative. His last song cycle published in 1828 after his death, “Schwanengesang,” is also an innovative contribution to German lieder literature, as it features poems by different poets—namely, Ludwig Rellstab, Heine, and Johann Gabriel Seidl. The Wiener Theaterzeitung, writing about “Winterreise” at the time, commented that it was a work that “none can sing or hear without being deeply moved.” Antonín Dvořák wrote in 1894 that Schubert, whom he considered one of the truly great composers, was clearly influential on shorter works, especially Lieder and shorter piano works: “The tendency of the romantic school has been toward short forms, and although Weber helped to show the way, to Schubert belongs the chief credit of originating the short models of piano forte pieces which the romantic school has preferably cultivated. [. . .] Schubert created a new epoch with the Lied. [. . .] All other songwriters have followed in his footsteps.”

Schubert’s compositional style progressed rapidly throughout his short life. A feeling of regret for the loss of potential masterpieces caused by his early death at age 31 was expressed in the epitaph on his large tombstone written by his friend the poet Franz Grillparzer: “Here music has buried a treasure, but even fairer hopes.” Some have disagreed with this early view, arguing that Schubert in his lifetime did produce enough masterpieces not to be limited to the image of an unfulfilled promise. This is in particular the opinion of pianists, including Alfred Brendel, who dryly billed the Grillparzer epitaph as “inappropriate.”

Schubert’s chamber music continues to be popular. In a poll, the results of which were announced in October 2008, the ABC in Australia found that Schubert’s chamber works dominated the field, with the Trout Quintet coming first, followed by two of his other works.

The New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini, who ranked Schubert as the fourth greatest composer, wrote of him,

You have to love the guy, who died at 31, ill, impoverished and neglected except by a circle of friends who were in awe of his genius. For his hundreds of songs alone—including the haunting cycle Winterreise, which will never release its tenacious hold on singers and audiences—Schubert is central to our concert life. . . . Schubert’s first few symphonies may be works in progress. But the Unfinished and especially the Great C major Symphony are astonishing. The latter one paves the way for Bruckner and prefigures Mahler.

If you’d like a deeper understanding of the life experiences of Franz Schubert, you can read the entirety of the Wikipedia article on him from which this has been drawn.

Der-Erlkönig

Please read this page on our first art song, “Der Erlkönig.” This piece is one of the best known lieder of the Romantic era and certainly one of Schubert’s most famous compositions. It is through composed in form, and the dramatic text is heightened by the fact that singers generally give the four characters featured in the poem slightly different tone qualities, a bit like an actor playing multiple parts. As the music is so expressive of the poem’s text, I’d encourage you to listen to the piece on the playlist as soon as you’ve read the article.

Introduction

“Erlknig” (also called “Der Erlknig”) is a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It depicts the death of a child assailed by a supernatural being, the Erlking or “Erlknig” (suggesting the literal translation “alder king,” but see below). It was originally composed by Goethe as part of a 1782 Singspiel entitled Die Fischerin.

The poem has been used as the text for Lieder (art songs for voice and piano) by many classical composers.

Summary

An anxious young boy is being carried home at night by his father on horseback. To what sort of home is not spelled out; German Hof has a rather broad meaning of “yard,” “courtyard,” “farm,” or (royal) “court.” The lack of specificity of the father’s social position allows the reader to imagine the details.

As the poem unfolds, the son seems to see and hear beings his father does not; the reader cannot know if the father is indeed aware of the presence, but he chooses to comfort his son, asserting reassuringly naturalistic explanations for what the child sees—a wisp of fog, rustling leaves, shimmering willows. Finally the child shrieks that he has been attacked. The father makes faster for the Hof. There he recognizes that the boy is dead.

Text

| Original German | Literal translation | Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

|

Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind? “Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?”— “Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir! “Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht, “Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn? “Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort “Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt; Dem Vater grauset’s, er reitet geschwind, |

Who rides, so late, through night and wind? “My son, why do you hide your face in fear?” “You dear child, come, go with me! “My father, my father, and hearest you not, “Do you, fine boy, want to go with me? “My father, my father, and don’t you see there “I love you, your beautiful form entices me; It horrifies the father; he swiftly rides on, |

Who rides there so late through the night dark and drear? “My son, wherefore seek’st thou thy face thus to hide?” “Oh, come, thou dear infant! oh come thou with me! “My father, my father, and dost thou not hear “Wilt go, then, dear infant, wilt go with me there? “My father, my father, and dost thou not see, “I love thee, I’m charm’d by thy beauty, dear boy! The father now gallops, with terror half wild, |

The Legend

The story of the Erlkönig derives from the traditional Danish ballad Elveskud: Goethe’s poem was inspired by Johann Gottfried Herder’s translation of a variant of the ballad (Danmarks gamle Folkeviser 47B, from Peter Syv’s 1695 edition) into German as “Erlkönigs Tochter” (“The Erl-king’s Daughter”) in his collection of folk songs, Stimmen der Völker in Liedern (published 1778). Goethe’s poem then took on a life of its own, inspiring the Romantic concept of the Erlking. Niels Gade’s cantata Elverskud opus 30 (1854, text by Chr. K. F. Molbech) was published in translation as Erlkönigs Tochter.

The Erlkönig’s nature has been the subject of some debate. The name translates literally from the German as “Alder King” rather than its common English translation, “Elf King” (which would be rendered as Elfenkönig in German). It has often been suggested that Erlkönig is a mistranslation from the original Danish elverkonge, which does mean “king of the elves.”

In the original Scandinavian version of the tale, the antagonist was the Erlkönig’s daughter rather than the Erlkönig himself; the female elves or elvermøer sought to ensnare human beings to satisfy their desire, jealousy, and lust for revenge.

Settings to Music

The poem has often been set to music with Franz Schubert’s rendition, his Opus 1 (D. 328), being the best known. Other notable settings are by members of Goethe’s circle, including the actress Corona Schröter (1782), Andreas Romberg (1793), Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1794), and Carl Friedrich Zelter (1797). Beethoven attempted to set it to music but abandoned the effort; his sketch, however, was complete enough to be published in a completion by Reinhold Becker (1897). A few other 19th century versions are those by Václav Tomášek (1815), Carl Loewe (1818), Ludwig Spohr (1856, with obbligato violin), and Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (Polyphonic Studies for Solo Violin). The 21st century examples are pianist Marc-André Hamelin’s “Etude No. 8 (after Goethe)” for solo piano, based on “Erlkönig,” and German rock singer Achim Reichel on his album Wilder Wassermann (2002).

The Franz Schubert Composition

Listen: Erlkönig

Please listen to the following audio file to hear Ernestine Schumann-Heink perform.

Franz Schubert composed his Lied, “Der Erlkönig,” for solo voice and piano in 1815, setting text from Goethe’s poem. Schubert revised the song three times before publishing his fourth version in 1821 as his Opus 1; it was cataloged by Otto Erich Deutsch as D. 328 in his 1951 catalog of Schubert’s works. The song was first performed in concert on 1 December 1820 at a private gathering in Vienna and received its public premiere on 7 March 1821 at Vienna’s Theater am Kärntnertor.

The four characters in the song—narrator, father, son, and the Erlking—are usually all sung by a single vocalist; occasionally, however, the work is performed by four individual vocalists (or three, with one taking the parts of both the narrator and the Erlking). Schubert placed each character largely in a different vocal range, and each has his own rhythmic nuances; in addition, most singers endeavor to use a different vocal coloration for each part. The piece modulates frequently, although each character changes between minor or major mode depending how each character intends to interact with the other characters.

- The Narrator lies in the middle range and begins in the minor mode.

- The Father lies in the lower range and sings in both minor and major mode.

- The Son lies in a higher range, also in the minor mode.

- The Erlking’s vocal line, in a variety of major keys, undulates up and down to arpeggiated accompaniment, providing the only break from the ostinato bass triplets in the accompaniment until the boy’s death. When the Erlking first tries to take the Son with him, he sings in C major. When it transitions from the Erlking to the Son, the modulation occurs, and the Son sings in g minor. The Erlking’s lines are typically sung in a softer dynamic in order to contribute to a different color of sound than that which is used previously. Schubert marked it pianissimo in the manuscript to show that the color needed to change.

A fifth character, the horse, is implied in rapid triplet figures played by the pianist throughout the work, mimicking hoof beats.

“Der Erlkönig” starts with the piano rapidly playing triplets to create a sense of urgency and simulate the horse’s galloping. The left hand of the piano part introduces a low register leitmotif composed of successive triplets. The right hand consists of triplets throughout the whole piece, up until the last three bars. The constant triplets drive forward the frequent modulations of the peace as it switches between the characters. This leitmotif, dark and ominous, is directly associated with the Erlkönig and recurs throughout the piece. These motifs continue throughout. As the piece continues, each of the son’s pleas become louder and higher in pitch than the last. Near the end of the piece, the music quickens and then slows as the father spurs his horse to go faster and then arrives at his destination. The absence of the piano creates multiple effects on the text and music. The silence draws attention to the dramatic text and amplifies the immense loss and sorrow caused by the son’s death. This silence from the piano also delivers the shock experienced by the father upon the realization that he has just lost his son to the elf king, despite desperately fighting to save the son from the elf kings grasp. The piece is regarded as extremely challenging to perform due to the multiple characters the vocalist is required to portray, as well as its difficult accompaniment, involving rapidly repeated chords and octaves that contribute to the drama and urgency of the piece.

Der Erlkönig is a through composed piece, meaning that with each line of text, there is new music. Although the melodic motives recur, the harmonic structure is constantly changing, and the piece modulates within characters. The elf king remains mainly in major mode due to the fact that he is trying to seduce the son into giving up on life. Using a major mode creates an effect where the elf king is able to portray a warm and inviting aura in order to convince the son that the afterlife promises great pleasures and fortunes. The son always starts singing in the minor mode and usually stays in it for his whole line. This is used to represent his fear of the elf king. Every time he sings the famous line “Mein Vater,” he sings it one step higher in each verse, starting first at a D and going up to an F on his final line. This indicates his urgency in trying to get his father to believe him as the elf king gets closer. For most of the Father’s lines, they begin in minor and end in major as he tries to reassure his son by providing rational explanations to his son’s hallucinations and dismissing the elf king. The constant in major and minor for the father may also represent the constant struggle and loss of control as he tries to save his son from the elf king’s persuasion.

The rhythm of the piano accompaniment also changes within the characters. The first time the elf king sings in measure 57, the galloping motive disappears. However, when the elf king sings again in measure 87, the piano accompaniment is arpeggiating rather than playing chords. The disappearance of the galloping motive is also symbolic of the son’s hallucinatory state.

Der Erlkönig has been transcribed for various settings: for solo piano by Franz Liszt; for solo voice and orchestra by Hector Berlioz; and for solo violin by Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst.

The Carl Lowe Composition

Carl Loewe’s setting was published as Op. 1, No. 3 and composed in 1817–18, in the lifetime of the poem’s author and also of Schubert, whose version Loewe did not then know. Collected with it were Op. 1, No. 1, Edward (1818; a translation of the Scottish ballad) and No. 2, Der Wirthin Töchterlein (1823; The Innkeeper’s Daughter), a poem of Ludwig Uhland. Inspired by a German translation of Scottish border ballads, Loewe set several poems with an elvish theme; but although all three of Op. 1 are concerned with untimely death, in this set only the “Erlkönig” has the supernatural element.

Loewe’s accompaniment is in semiquaver groups of six in nine-eight time and marked Geschwind (fast). The vocal line evokes the galloping effect by repeated figures of crotchet and quaver, or sometimes three quavers, overlying the binary tremolo of the semiquavers in the piano. In addition to an unusual sense of motion, this creates a very flexible template for the stresses in the words to fall correctly within the rhythmic structure.

Loewe’s version is less melodic than Schubert’s, with an insistent, repetitive harmonic structure between the opening minor key and answering phrases in the major key of the dominant, which have a stark quality owing to their unusual relationship to the home key. The narrator’s phrases are echoed by the voices of father and son, the father taking up the deeper, rising phrase, and the son a lightly undulating, answering theme around the dominant fifth. These two themes also evoke the rising and moaning of the wind. The Elf king, who is always heard pianissimo, does not sing melodies but instead delivers insubstantial rising arpeggios that outline a single major chord (that of the home key), which sounds simultaneously on the piano in una corda tremolo. Only with his final threatening word, “Gewalt,” does he depart from this chord. Loews implication is that the Erlking has no substance but merely exists in the child’s fevered imagination. As the piece progresses, the first in the groups of three quavers are dotted to create a breathless pace, which then forms a bass figure in the piano driving through to the final crisis. The last words, war tot, leap from the lower dominant to the sharpened third of the home key, this time not to the major but to a diminished chord, which settles chromatically through the home key in the major and then to the minor.

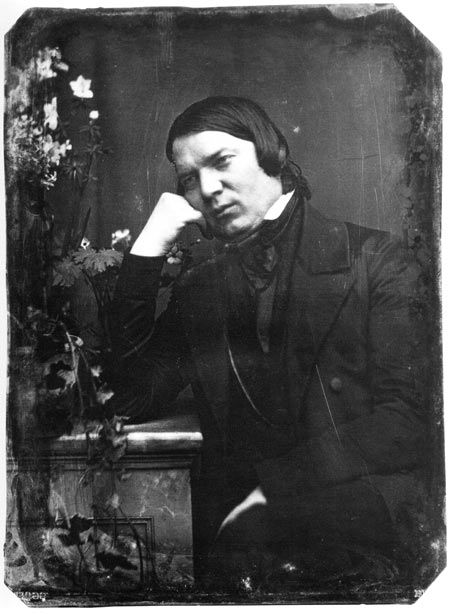

Robert Schumann

The early Romantic composer Robert Schumann was, like Schubert, a prolific composer of art songs. Also like Schubert, his life was tragically cut short, though unlike the younger composer, Robert enjoyed a good deal more success and recognition. This short introduction is a good summary of the composer’s career. If you’d like to know more, I’d certainly encourage you to read the rest of the article here. The article includes links to additional pieces not on our listening exam. It also tells the story of Robert and Clara Schumann, which is one of the great love stories of music history. Clara Schumann was as formidable a musician as her husband, and as a performer (concert pianist), she was quite famous. She and her husband were both very influential in the life of one of the other composers we will study in this period: Johannes Brahms.

Robert Schumann (8 June 1810–29 July 1856) was a German composer and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a virtuoso pianist. He had been assured by his teacher Friedrich Wieck that he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but a hand injury ended this dream. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing.

Schumann’s published compositions were written exclusively for the piano until 1840; he later composed works for piano and orchestra; many Lieder (songs for voice and piano); four symphonies; an opera; and other orchestral, choral, and chamber works. Works such as Kinderszenen, Album die Jugend, Blumenstack, the Sonatas, and Albumbltter are among his most famous. His writings about music appeared mostly in the Neue Zeitschrift Musik (New Journal for Music), a Leipzig based publication that he jointly founded.

In 1840, against the wishes of her father, Schumann married Friedrich Wieck’s daughter Clara following a long and acrimonious legal battle, which found in favor of Clara and Robert. Clara also composed music and had a considerable concert career as a pianist, the earnings from which formed a substantial part of her father’s fortune.

Schumann suffered from a lifelong mental disorder, first manifesting itself in 1833 as a severe melancholic depressive episode, which recurred several times alternating with phases of “exaltation” and increasingly also delusional ideas of being poisoned or threatened with metallic items. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted to a mental asylum, at his own request, in Endenich near Bonn. Diagnosed with “psychotic melancholia,” Schumann died two years later in 1856 without having recovered from his mental illness.

“Du Ring an Meinem Finger” is part of a larger cycle of songs called Frauenliebe und Leben. You can download this scan of a public domain score to the song cycle if you would like to review the printed music.

Introduction

Frauenliebe und Leben (A Woman’s Love and Life) is a cycle of poems by Adelbert von Chamisso written in 1830. They describe the course of a woman’s love for her man, from her point of view, from first meeting, through marriage, to his death, and after. Selections were set to music as a song cycle by masters of German Lied—namely, Carl Loewe, Franz Paul Lachner, and Robert Schumann. The setting by Schumann (his opus 42) is now the most widely known.

Schumann’s Cycle

Schumann wrote his setting in 1840, a year in which he wrote so many lieder (including three other song cycles: Liederkreis Op. 24 and Op. 39, Dichterliebe) that it is known as his “year of song.” There are eight poems in his cycle, together telling a story from the protagonist first meeting her love, through their marriage, to his death. They are:

- “Seit ich ihn gesehen” (“Since I Saw Him”)

- “Er, der Herrlichste von allen” (“He, the Noblest of All”)

- “Ich kann’s nicht fassen, nicht glauben” (“I Cannot Grasp or Believe It”)

- “Du Ring an meinem Finger” (“You Ring Upon My Finger”)

- “Helft mir, ihr Schwestern” (“Help Me, Sisters”)

- “Süßer Freund, du blickest mich verwundert an” (“Sweet Friend, You Gaze”)

- “An meinem Herzen, an meiner Brust” (“At My Heart, At My Breast”)

- “Nun hast du mir den ersten Schmerz getan” (“Now You Have Caused Me Pain for the First Time”)

Schumann’s choice of text was very probably inspired in part by events in his personal life. He had been courting Clara Wieck but had failed to get her father’s permission to marry her. In 1840, after a legal battle to make such permission unnecessary, he finally married her.

The songs in this cycle are notable for the fact that the piano has a remarkable independence from the voice. Breaking away from the Schubertian ideal, Schumann has the piano contain the mood of the song in its totality. Another notable characteristic is the cycle’s cyclic structure, in which the last movement repeats the theme of the first.

“Du Ring an meinem Finger” from Frauenliebe und Leben

Composer: Robert Schumann

Tempo: Score markings indicate “intimate” (suggesting slow tempo) with the second half marked “gradually faster”

Voice part: Mezzo-soprano or soprano

Form: Rondo

| German | English |

| Du Ring an meinem Finger, | You ring on my finger |

| Mein goldenes Ringelein, | My little golden ring, |

| Ich drücke dich fromm an die Lippen, | I press you with devotion to my lips |

| Dich fromm an das Herze mein. | With devotion to my heart. |

| Ich hatt ihn ausgeträumt, | I had dreamed it |

| Der Kindheit friedlich schönen Traum, | The beautiful, peaceful dream of childhood |

| Ich fand allein mich, verloren | I found myself alone, lost |

| Im öden, unendlichen Raum. | In the barren, infinite space. |

| Du Ring an meinem Finger | You ring on my finger |

| Da hast du mich erst belehrt, | You have first taught me, |

| Hast meinem Blick erschlossen | Have opened my eyes |

| Des Lebens unendlichen, tiefen Wert. | Life’s infinite, deep value. |

| Ich will ihm dienen, ihm leben, | I want to serve him, live for him |

| Ihm angehören ganz, | Belong to him completely |

| Hin selber mich geben und finden | Giving and finding myself |

| Verklärt mich in seinem Glanz. | Transformed in his glory. |

| Du Ring an meinem Finger, | You ring on my finger |

| Mein goldenes Ringelein, | My little golden ring, |

| Ich drücke dich fromm an die Lippen | I press you with devotion to my lips |

| Dich fromm an das Herze mein. | With devotion to my heart. |

The Piano

This seems like a good time to examine the history of the piano. The pianos played by the composers of the Romantic era had evolved considerably from those played by Mozart and even Beethoven. This page will give you a sense of that historical development.

History of the Piano

The piano was founded on earlier technological innovations that date back to the Middle Ages. By the early Baroque, there were two primary stringed keyboard instruments: the clavichord and the harpsichord. The invention of the piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, Italy, who was an expert harpsichord maker and was well acquainted with the body of knowledge on stringed keyboard instruments. The instruments of Cristofori’s day possessed individual strengths and weaknesses. The clavichord allowed expressive control of the sound volume and sustain but was too quiet for large performances. The harpsichord produced a sufficiently loud sound but had little expressive control over each note. These tonal differences were due to the mechanisms of the two instruments. In a clavichord, the strings are struck by tangents, while in a harpsichord, they are plucked by quills. The piano was probably formed as an attempt to combine loudness with control, avoiding the trade offs of available instruments.

Cristofori’s great success was solving, with no prior example, the fundamental mechanical problem of piano design: the hammer must strike the string, but not remain in contact with it (as a tangent remains in contact with a clavichord string) because this would damp the sound. Moreover, the hammer must return to its rest position without bouncing violently, and it must be possible to repeat a note rapidly. Cristofori’s piano action was a model for the many approaches to piano actions that followed. His early instruments were made with thin strings and were much quieter than the modern piano, but much louder and with more sustain in comparison to the clavichord—the only previous keyboard instrument capable of dynamic nuance via the keyboard.

Cristofori’s new instrument remained relatively unknown until an Italian writer, Scipione Maffei, wrote an enthusiastic article about it in 1711, including a diagram of the mechanism. This article was widely distributed, and most of the next generation of piano builders started their work due to reading it. One of these builders was the organ builder Gottfried Silbermann, who showed Johann Sebastian Bach one of his early instruments in the 1730s. Bach did not like it at that time, claiming that the higher notes were too soft to allow a full dynamic range. Although this earned him some animosity from Silbermann, the criticism was apparently heeded. Bach did approve of a later instrument he saw in 1747 and even served as an agent in selling Silbermann’s pianos.

Piano making flourished in late 18th century Vienna. Viennese style pianos were built with wood frames, two strings per note, and had leather covered hammers. Some of these Viennese pianos had the opposite coloring of modern day pianos; the natural keys were black and the accidental keys white. It was for such instruments that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed his concertos and sonatas, and replicas of them are built today for use in authentic instrument performance of his music. The pianos of Mozart’s day had a softer, more ethereal tone than today’s pianos, with less sustaining power. The term fortepiano is now used to distinguish the 18th century instrument from later pianos.

In the period lasting from about 1790 to 1860, the Mozart era piano underwent tremendous changes that led to the modern form of the instrument. This revolution was in response to a preference by composers and pianists for a more powerful, sustained piano sound and made possible by the ongoing Industrial Revolution with resources such as high quality piano wire for strings and precision casting for the production of iron frames. Over time, the range of the piano was also increased from the five octaves of Mozart’s day to the 7⅓ or more octaves found on modern pianos. This growth can be heard over the course of Beethoven’s career. Beethoven’s later piano works feature a wider range of pitches than earlier works as the instrument’s pitch range grew. To understand the impact of this expansion more clearly, a numeric illustration may be helpful. A five octave piano would have roughly 60 keys, while today’s pianos generally feature 88.

Technical innovations continued to be added to the piano as various instrument makers experimented with ways to improve the instrument’s mechanical function and tonal expression. By the late 19th century, the piano had evolved into the powerful 88-key instrument we recognize today. It is important to remember that much of the music of the Classical era was composed for a type of instrument (the fortepiano) that is rather different from the instrument on which it is now played. Even the music of the Romantic period, including that of Chopin, Schumann, and Brahms, was written for pianos substantially different from modern pianos.

Frederic Chopin

Frederic Chopin’s compositional output was relatively small but had an enormous influence, particularly on piano music. All his music featured the piano in one capacity or another.

Introduction

Frédéric François Chopin (22 February or 1 March 1810–17 October 1849), born Frederic Francois Chopin, was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic era who wrote primarily for the solo piano. He gained and has maintained renown worldwide as one of the leading musicians of his era, whose poetic genius was based on a professional technique that was without equal in his generation. Chopin was born in what was then the Duchy of Warsaw and grew up in Warsaw, which after 1815 became part of Congress Poland. A child prodigy, he completed his musical education and composed many of his works in Warsaw before leaving Poland at the age of 20, less than a month before the outbreak of the November 1830 Uprising.

At the age of 21, he settled in Paris. Thereafter, during the last 18 years of his life, he gave only some 30 public performances, preferring the more intimate atmosphere of the salon. He supported himself by selling his compositions and teaching piano, for which he was in high demand. Chopin formed a friendship with Franz Liszt and was admired by many of his musical contemporaries, including Robert Schumann. In 1835 he obtained French citizenship. After a failed engagement to a Polish girl, from 1837 to 1847 he maintained an often troubled relationship with the French writer George Sand. A brief and unhappy visit to Majorca with Sand in 1838–39 was one of his most productive periods of composition. In his last years, he was financially supported by his admirer Jane Stirling, who also arranged for him to visit Scotland in 1848. Through most of his life, Chopin suffered from poor health. He died in Paris in 1849, probably of tuberculosis.

All of Chopin’s compositions include the piano. Most are for solo piano, though he also wrote two piano concertos, a few chamber pieces, and some songs to Polish lyrics. His keyboard style is highly individual and often technically demanding; his own performances were noted for their nuance and sensitivity. Chopin invented the concept of instrumental ballade. His major piano works also include sonatas, mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes, polonaises, études, impromptus, scherzos, and preludes, some published only after his death. Many contain elements of both Polish folk music and of the classical tradition of J. S. Bach, Mozart, and Schubert, the music of all of whom he admired. His innovations in style, musical form, and harmony and his association of music with nationalism were influential throughout and after the late Romantic period.

Both in his native Poland and beyond, Chopin’s music, his status as one of music’s earliest superstars, his association (if only indirect) with political insurrection, his love life, and his early death have made him, in the public consciousness, a leading symbol of the Romantic era. His works remain popular, and he has been the subject of numerous films and biographies of varying degrees of historical accuracy.

Nocturne in C# Minor

Before we dive into this nocturne, let’s get a little background on the genre itself. Here is a quote from the Wikipedia article on the musical genre Nocturne:

In its more familiar form as a single movement character piece usually written for solo piano, the nocturne was cultivated primarily in the 19th century. The first nocturnes to be written under the specific title were by the Irish composer John Field, generally viewed as the father of the Romantic nocturne that characteristically features a cantabile (songlike) melody over an arpeggiated, even guitar-like accompaniment. However, the most famous exponent of the form was Frederic Chopin, who wrote 21 of them.

Nocturnes, as the name suggests, generally exhibit a brooding or melancholy mood. There is relatively little to read on this page, and the first of the two paragraphs is more informative for our purposes, as it focuses on musical elements such as tempo and form rather than on critical opinion. However, I think there is value in reading both paragraphs, as the descriptive language provided by the cited critics may provide associations that will help you with identification.

Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1

The Nocturne in C-sharp minor is initially marked larghetto and is in 4/4 meter. It transitions to pi mosso (more movement) in measure 29. The piece returns to its original tempo in measure 84 and ends in an adagio beginning in measure 99. The piece is 101 measures long and written in ternary form with coda; the primary theme is introduced, followed by a secondary theme and a repetition of the first.

The opening alternates between major and minor and uses arpeggios, commonly found in other nocturnes as well, in the left hand. It sounds “morbid and intentionally grating.” James Friskin noted that the piece requires an “unusually wide extension of the left hand” in the beginning and called the piece “fine and tragic.” James Huneker commented that the piece is “a masterpiece,” pointing to the “morbid, persistent melody” of the left hand. For David Dubal, the pi mosso has a “restless, vehement power.” Huneker also likens the pi mosso to a work by Beethoven due to the agitated nature of this section. The coda “reminds the listener of Chopin’s seemingly inexhaustible prodigality,” according to Dubal, while Huneker calls it a “surprising climax followed by sunshine” before returning to the opening theme.

Listen

Please listen to the following audio file to listen to Nocturne No. 7.

Excerpts

Program Music and the Program Symphony

Program Music

Program music or programme music (British English) is music that attempts to depict in music an extra musical scene or narrative. The narrative itself might be offered to the audience in the form of program notes inviting imaginative correlations with the music. A well known example is Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, which relates a drug induced series of morbid fantasies concerning the unrequited love of a sensitive poet involving murder, execution, and the torments of Hell. The genre culminates in the symphonic works of Richard Strauss that include narrations of the adventures of Don Quixote, Till Eulenspiegel, the composer’s domestic life, and an interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy of the Superman. Following Strauss, the genre declined, and new works with explicitly narrative content are rare. Nevertheless, the genre continues to exert an influence on film music, especially where this draws upon the techniques of late Romantic music.

The term is almost exclusively applied to works in the European classical music tradition, particularly those from the Romantic music period of the 19th century, during which the concept was popular, but programmatic pieces have long been a part of music. The term is usually reserved for purely instrumental works (pieces without singers and lyrics) and not used, for example for Opera or Lieder. Single movement orchestral pieces of program music are often called symphonic poems.

Absolute music, in contrast, is to be appreciated without any particular reference to anything outside the music itself.

Program Symphony

Any instrumental genre could be composed in such a way as to tell a story or paint a picture in the mind’s eye of the listener. A program symphony is the result of a composer applying the principle of program music to the genre of the symphony. A program symphony, like any other work of that genre, would consist of multiple movements, usually four or five, and would likely follow to some extent the standard characteristics of symphonic construction. For example, the second movement would likely be slower than the first, and the third movement would be based on a dance. The fifth movement would serve as a kind of grand finale. Traditional forms would be of less concern to a composer of programmatic music, as the form of a movement would likely be influenced by the subject matter being depicted. Hector Berlioz’s Symphony Fantastique is one of the best known examples of a program symphony.

Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz was an early Romantic innovator. His music was not always appreciated in his day, though he certainly enjoyed a fair amount of success. Prone to sudden emotional swings, his personality seems to come through in the music in his ability to draw unusual sounds out of the orchestra. He is still studied today as a master orchestrator. His instrumental music was often programmatic, and his Symphonie Fantastique is one of the quintessential examples of orchestral storytelling. The final movement of that program symphony is on our playlist. Read this biography to learn about his life.

Symphonie Fantastique

This page article provides an excellent overview of one of Berlioz’s best known works, Symphonie Fantastique. I encourage you to read through the description of each of the movements of the piece, but of course the one that will be most important for you in our class is the description of the 5th and final movement, as that is the piece on our playlist. Try listening to the piece while you review the outline of the fifth movement to see if you can hear all the unusual orchestral effects described there.

Introduction

Symphonie fantastique: (Fantastical Symphony: An Episode in the Life of an Artist, in Five Parts) Op. 14 is a program symphony written by the French composer Hector Berlioz in 1830. It is an important piece of the early Romantic period and is popular with concert audiences worldwide. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire in December 1830. The work was repeatedly revived after 1831 and subsequently became a favorite in Paris.

Leonard Bernstein described the symphony as the first musical expedition into psychedelia because of its hallucinatory and dream like nature, and because history suggests Berlioz composed at least a portion of it under the influence of opium. According to Bernstein, “Berlioz tells it like it is. You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral.”

In 1831, Berlioz wrote a lesser known sequel to the work, Lélio, for actor, orchestra and chorus. Franz Liszt made a piano transcription of the symphony in 1833 (S.470).

Outline

The symphony is a piece of program music that tells the story of an artist gifted with a lively imagination who has poisoned himself with opium in the depths of despair because of hopeless love. Berlioz provided his own program notes for each movement of the work (see below). He prefaces his notes with the following instructions:

The composer’s intention has been to develop various episodes in the life of an artist, in so far as they lend themselves to musical treatment. As the work cannot rely on the assistance of speech, the plan of the instrumental drama needs to be set out in advance. The following programme must therefore be considered as the spoken text of an opera, which serves to introduce musical movements and to motivate their character and expression.

There are five movements instead of the four movements that were conventional for symphonies at the time:

- Rêveries—Passions (Reveries Passions)

- Un bal (A Ball)

- Scène aux champs (Scene in the Fields)

- Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold)

- Songe d’une nuit du sabbat (Dream of the Night of the Sabbath)

First Movement: “Rêveries—Passions” (Reverie—Passions)

In Berlioz’s own program notes from 1845, he writes:

The author imagines that a young musician, afflicted by the sickness of spirit which a famous writer has called the vagueness of passions [le vague des passions], sees for the first time a woman who unites all the charms of the ideal person his imagination was dreaming of, and falls desperately in love with her. By a strange anomaly, the beloved image never presents itself to the artist’s mind without being associated with a musical idea, in which he recognizes a certain quality of passion, but endowed with the nobility and shyness which he credits to the object of his love.

This melodic image and its model keep haunting him ceaselessly like a double idée fixe. This explains the constant recurrence in all the movements of the symphony of the melody which launches the first allegro. The transitions from this state of dreamy melancholy, interrupted by occasional upsurges of aimless joy, to delirious passion, with its outbursts of fury and jealousy, its returns of tenderness, its tears, its religious consolations all this forms the subject of the first movement.

“The first movement is radical in its harmonic outline, building a vast arch back to the home key; while similar to the sonata form of the classical period, Parisian critics regarded this as unconventional. It is here that the listener is introduced to the theme of the artist’s beloved, or the idée fixe. Throughout the movement there is a simplicity in the way melodies and themes are presented, which Robert Schumann likened to ‘Beethoven’s epigrams’ ideas that could be extended had the composer chosen to. In part, it is because Berlioz rejected writing the more symmetrical melodies then in academic fashion, and instead looked for melodies that were ‘so intense in every note as to defy normal harmonization,’ as Schumann put it.” —Hector Berlioz: The Complete Guide

The theme itself was taken from Berlioz’s scene lyrique “Herminie,” composed in 1828.

Second Movement: “Un bal” (A Ball)

Again, quoting from Berlioz’s program notes:

The artist finds himself in the most diverse situations in life, in the tumult of a festive party, in the peaceful contemplation of the beautiful sights of nature, yet everywhere, whether in town or in the countryside, the beloved image keeps haunting him and throws his spirit into confusion.

The second movement has a mysterious sounding introduction that creates an atmosphere of impending excitement, followed by a passage dominated by two harps; then the flowing waltz theme appears, derived from the idée fixe at first, then transforming it. More formal statements of the idée fixe twice interrupt the waltz.

The movement is the only one to feature the two harps, providing the glamour and sensual richness of the ball, and may also symbolize the object of the young man’s affection. Berlioz wrote extensively in his memoirs of his trials and tribulations in having this symphony performed due to a lack of capable harpists and harps, especially in Germany.

Another feature of this movement is that Berlioz added a part for solo cornet to his autograph score, although it was not included in the score published in his lifetime. The work has most often been played and recorded without the solo cornet part. Conductors Jean Martinon, Sir Colin Davis, Otto Klemperer, Gustavo Dudamel, and Leonard Slatkin have employed this part for cornet in performances of the symphony.

Third Movement: “Scène aux champs” (Scene in the Fields)

From Berlioz’s program notes:

One evening in the countryside he hears two shepherds in the distance dialoguing with their “ranz des vaches”; this pastoral duet, the setting, the gentle rustling of the trees in the wind, some causes for hope that he has recently conceived, all conspire to restore to his heart an unaccustomed feeling of calm and to give to his thoughts a happier colouring. He broods on his loneliness, and hopes that soon he will no longer be on his own . . . But what if she betrayed him! . . . This mingled hope and fear, these ideas of happiness, disturbed by dark premonitions, form the subject of the adagio. At the end one of the shepherds resumes his “ranz des vaches”; the other one no longer answers. Distant sound of thunder . . . solitude . . . silence.

The two “shepherds” Berlioz mentions in the notes are depicted with a cor anglais (English horn) and an offstage oboe tossing an evocative melody back and forth. After the cor anglais oboe conversation, the principal theme of the movement appears on solo flute and violins. Berlioz salvaged this theme from his abandoned Messe solennelle. The idée fixe returns in the middle of the movement, played by oboe and flute. The sound of distant thunder at the end of the movement is a striking passage for four timpani.

Fourth Movement: “Marche au supplice” (March to the Scaffold)

From Berlioz’s program notes:

Convinced that his love is unappreciated, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. As he cries for forgiveness the effects of the narcotic set in. He wants to hide but he cannot so he watches as an onlooker as he dies. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow when his head bounced down the steps.

Berlioz claimed to have written the fourth movement in a single night, reconstructing music from an unfinished project—the opera Les francs-juges. The movement begins with timpani sextuplets in thirds, for which he directs, “The first quaver of each half bar is to be played with two drumsticks, and the other five with the right hand drumsticks.” The movement proceeds as a march filled with blaring horns and rushing passages and scurrying figures that later show up in the last movement. Before the musical depiction of his execution, there is a brief, nostalgic recollection of the idée fixe in a solo clarinet, as though representing the last conscious thought of the soon to be executed man. Immediately following this is a single, short fortissimo G minor chord—the fatal blow of the guillotine blade, followed by a series of pizzicato notes representing the rolling of the severed head into the basket. After his death, the final nine bars of the movement contain a victorious series of G major brass chords, along with rolls of the snare drums within the entire orchestra, seemingly intended to convey the cheering of the onlooking throng.

Fifth Movement: “Songe d’une nuit du sabbat” (Dream of the Night of the Sabbath)

From Berlioz’s program notes:

He sees himself at a witches sabbath, in the midst of a hideous gathering of shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind who have come together for his funeral. Strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter; distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts. The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque: it is she who is coming to the sabbath. . . . Roar of delight at her arrival. . . . She joins the diabolical orgy . . . The funeral knell tolls, burlesque parody of the Dies irae, the dance of the witches. The dance of the witches combined with the Dies irae.

This movement can be divided into sections according to tempo changes:

- The introduction is Largo, in common time, creating an ominous quality through dynamic variations and instrumental effects, particularly in the strings (tremolos, pizz, sf).

- At bar 21, the tempo changes to Allegro and the metronome to 6/8. The return of the idée fixe as a “vulgar dance tune” is depicted by the C clarinet. This is interrupted by an Allegro Assai section in cut common at bar 29.

- The idée fixe then returns as a prominent E-flat clarinet solo at bar 40, in 6/8 and Allegro. The E-flat clarinet contributes a sharper, more shrill timbre than the C clarinet.

- At bar 80, there is one bar of alla breve, with descending crotchets in unison through the entire orchestra. Again in 6/8, this section sees the introduction of tubular bells and fragments of the “witches’ round dance.”

- The “Dies irae” begins at bar 127, the motif derived from the 13th century Latin sequence. It is initially stated in unison between the unusual combination of four bassoons and two tubas.

- At bar 222, the “witches’ round dance” motif is repeatedly stated in the strings, to be interrupted by three syncopated notes in the brass. This leads into the Ronde du Sabbat (Sabbath Round) at bar 241, where the motif is finally expressed in full.

- The Dies irae et Ronde du Sabbat Ensemble section is at bar 414.

There are a host of effects, including eerie col legno in the strings—the bubbling of the witches’ cauldron to the blasts of wind. The climactic finale combines the somber Dies Irae melody with the wild fugue of the Ronde du Sabbat.

-

The aim of the second kind of imitation, as we have said before, is to reproduce the intonations of the passions and the emotions, and even to trace a musical image, or metaphor, of objects that can only be seen. The continual interruption of the Dies irae motif by the strings symbolizes this continual fight of death until the movement and piece eventually, as we all do given in to the Dies irae theme and our eventual but necessary deaths.

He later adds:

-

Emotional (imitation) is designed to arouse in us by means of sound the notion of the several passions of the heart, and to awaken solely through the sense of hearing the impressions that human beings experience only through the other senses. Such is the goal of expression, depiction or musical metaphors.

As part of this, he uses an example of cyclical structure—an idea drawn from Beethoven’s use of similar rhythmic structures in his Fifth Symphony, and the idea of musical “cycles,” such as a “song cycle.” Berlioz did not know of Mendelssohn’s Octet, which also uses this device.

Introduction to Romantic Opera

This section contains information on major trends and composers in Romantic opera. We will be focusing our study on developments in the Italian and German operatic traditions. There was also a good deal of innovation taking place in Paris in the 19th century, but Verdi (Italian) and Wagner (German) were the most influential composers of the era, so we’ll be limiting our reading to those two national styles.

This section includes the following pages:

- Slide Show: Romantic Opera

- Early Romantic Opera

- Later Romantic Opera

- Trends in German and Italian Opera

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Rigoletto

- La donna e mobile

- Verdi’s Requiem

- Richard Wagner

- Tristan und Isolde

- Liebestod

- Verismo

- Giacomo Pucinni

- La Boheme

- Che gelida manina

- Si, mi chiamano Mimi

Early Romantic Era

As you read about the composers and operas we study in this class, you’ll hear frequent references to other earlier composers. Please read this brief background on the composers and trends that led to the later Romantic operas we will focus on. This site uses the term “vamp” to refer to the simple chordal accompaniment heard supporting bel canto arias. In the United States, that term tends to refer to a repeated accompaniment or ostinato, but the Scottish site we’re linking to uses it to mean a particular way of repeating a simple chord. View their site’s definition of vamp here along with a music example.

Later Romantic Era

While this article doesn’t cover all the operatic composers that we listen to in our class, it does provide a helpful summary of the Italian and German operatic traditions in the late 19th century. It also provides some helpful listening prompts for understanding the characteristics of the music of Verdi and Wagner. Please read this article carefully, and be sure to look up any musical terms that are unfamiliar using the site’s “A to Z Dictionary.” The link for that dictionary is found on the lower left of the page. Terms like leitmotif, bel canto, or rubato may appear on Exam 4 Terminology.

Trends in German and Italian Opera

These few paragraphs drill down a bit deeper into the styles of the three opera composers we’ll study: Verdi, Wagner, and Puccini. I don’t want to give the impression that nothing was happening in opera outside of Italy and Germany. Paris was a major center of opera composition in the 19th century, and there were world class opera houses in Prague and London that are still operating today. We simply have to pare down our focus in a one semester survey course like this, and Verdi and Wagner were the biggest names in the business.

Bel canto, Verdi, and Verismo

Listen

La donna è mobile

Please listen to the following audio file to hear Enrico Caruso sing “La donna è mobile” from Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto (1908).

No Pagliaccio non son

Please listen to the following audio file to hear an aria from Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, performed by Enrico Caruso.