6 Chapter 6: Impressionism to Modern

The Beginnings of Modernism

Manet’s Early Modernism

Edouard Manet has often been described as a “painter of modern life.” He was a friend of the Impressionists but never joined their group officially; one could say that his paintings are precursors to the themes and the aesthetics that the Impressionists embraced in the 1870s. In 1863, the Salon jury was especially severe. Many younger, emerging artists were refused. Some of them wrote a letter to Napoleon III, requesting a separate Salon to display the refused works so that the public could judge for itself whether the jury was right. Surprisingly, Napoleon III granted the request, and for once, a “Salon des Refusées” (Exhibition of artists denied admission to the official Salon) was held. One work in this Salon of Refused Artists immediately attracted much negative attention: this was Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe or Luncheon in the Grass. It caused an instant public scandal because of the alleged indecency of two fully dressed contemporary men (identifiable as students by their attire) who were accompanied by scantily dressed naked women. According to social codes, nudity was only acceptable when presented in the context of classical antiquity or Orientalism.

Edouard MANET (1832–1883) was a French Realist painter that transitioned from Realism to Impressionism. His paintings of the 1860s were more Realist, and the ones he painted in the 1870s–1880s were more Impressionistic.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863.

Manet shocked the French public with this painting because of a nude woman lunching in public with two fully dressed men, especially because the figures were recognizable. The nude was Manet’s model Victorine Meurend. The two men are Manet’s brother Gustave in the student’s hat with the tassel and his future brother in law, Ferdinand Leenhoff. It is said that the woman in the background is doing something a French woman at this time would have done if outdoors and needed to relieve herself; she is peeing in the stream. This is very similar to an earlier painting by Giorgione, Fete Champetre.

19th-Century IMPRESSIONISM

Impressionism evolved in Paris in the 1860s and continued into the early 20th century. It rarely responded to political events; politics had no impact on Impressionist imagery. The preference was for genre painting: scenes depicting everyday life and people, especially scenes of leisure activities, entertainment, and landscape.. It was influenced by Japanese prints and new developments in photography rather than by politics. Artists were interested in the natural properties of light, times of day, weather conditions, and seasons but also used effects of interior and artificial lighting, such as theater spotlights and café lanterns. The Montmartre district of Paris is where they congregated. They mounted 8 exhibitions of their own work between 1874–1886 because of rejection in the Salon. Impressionism had a greater impact internationally than previous styles. But what makes Impressionist art modern? Among other characteristics, one can cite the contemporary subject matter. The Impressionists sought to capture the fleeting moment, the reflection of light on surfaces, and the treatment of light as if it were a physical substance. The name Impressionism came from Monet’s painting Impression of a Sunrise.

Claude MONET (1840–1926) Impressionism

Claude Monet can rightly be described as the leader of the Impressionist group and a pioneer of Impressionist aesthetics. Atmospheric effects, broken brushstrokes, choice of modern subject matter, light, and optimistic colors are among the characteristics defining Impressionist art.

- He embodied the technical principles of Impressionism

- A painter of landscape who studied light and color with great intensity

- The term Impressionism came from a critic’s negative view of Monet’s Impression: Sunrise

- Famous for his water lilies

- Painted more outdoors than in a studio, plein air

Plein air = “open air,” means they painted outdoors.

Claude Monet, 1872, Impression of a Sunrise, Oil on canvas, 18.9 x 24.8

Hilaire Germain Edgar DEGAS (1834–1917) Degas: Impressionism

Impressionist painter Edgar Degas’s preferred subject matter covered the range from life along the boulevards and in the cafes to the racetracks and brothels, but he was especially drawn to theater and ballet. Degas had family ties to New Orleans, from where his mother’s family originated. Shortly before joining the Impressionists, he had visited the Crescent City. Most of Degas’s ballet scenes are actually pastel drawings and not oil paintings, this example being an exception to the rule. When depicting ballet, Degas focused on rehearsals, not the final performance. In this way, the ballet rehearsals were portrayed for what they really were: hard work, not play. The young girls rehearsing tended to have a lower- or working-class background. Degas was drawn to the lower classes in his art. Note the cropping of the figure on the right. This compositional choice was almost certainly an idea that Degas copied from photography.

Degas, The Dance Class, 1873–1876, oil on canvas

- French artist

- Refused to be classified as an Impressionist; he believed he was a Realist

- Never felt he was finished with a painting

- Also a sculptor and amateur photographer

- Spent time in New Orleans with his brothers who lived there

- Variety of subject matter but mostly known for his ballet dancers

Mary CASSATT (1845–1926) was an American painter and printmaker. She spent most of her adult life in France, where she became friends with Degas. Cassatt’s subject matter focused mostly on women, especially the bond between mother and child.

- American artist in France

- From a wealthy family

- Close friend to Degas

- Bold planes of color, sharp outlines, and compressed spaces (close-up views)

- Helped the Impressionists out by urging her friends and relatives to buy their paintings

- Because she was a woman, her subject matter tends to relate to family relationships or women

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party, 1893–94, oil on canvas

Auguste RODIN (1840–1917)

- French sculptor

- Well-known sculptor of the 19th century

- Influenced the 20th-century sculptors

- The Thinker, 1881

- One of his best-known works

- Influenced by Italian Renaissance sculpture of the monumental human figure

- Evolved from his plan to represent Dante

- Reflects Michelangelo’s Jeremiah and Durer’s Melencolia

- Tension and energy, meditative figures

Rodin, The Thinker, 1881, bronze

POST-IMPRESSIONISM and the Late 19th Century

Post-Impressionist artists are not a coherent group. They did not meet in a coffee house or show their works together in group shows, as did the Impressionists. Rather, the term is an expression of convenience, coined by critics and art historians after the fact in order to summarize a variety of modernist art movements and individual artists who benefitted from the opening up of the art world to modern subject matter and artistic subjectivity. It is therefore an umbrella term that includes a wide variety of artists, ranging from the Pointillist Seurat, to the individualists Gauguin and van Gogh, and finally Cézanne, who became a role model for the 20th-century Cubists.

- Means “after Impressionism”

- Influenced by Impressionism

- Drawn to bright colors and visible, distinctive brushstrokes like the Impressionists

- But the forms do not dissolve into the medium like Monet’s works, they are usually clear edged

- Formal structure (like Cezanne and Seurat) and emotional content (like Gauguin and van Gogh)

- Also influenced by the late 19th-century Symbolist movement

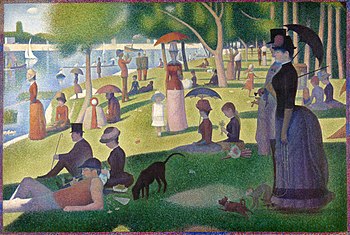

Seurat: Pointillism

The Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is Seurat’s uncontested masterwork. The Grande Jatte is the name of an island in the river Seine, not far from Asnières. It also served as a fashionable picnic ground for mostly an upper-class clientele. The work features a full-fledged Pointillist technique. Pointillism is a painting technique of small dots of color that are applied to create an image. Like Caillebotte, Seurat focused in this picture mostly on members of the haute bourgeoisie (upper middle class), whom he intended to mock. The lady, on the right, for instance, is walking a pet monkey; her skirt seems to bulge unnaturally; the monkey’s curling tail is mirrored by the seated gentleman’s cane on the left, etc. Overall, there is a stiff, classical air to the composition, whose figures move like silhouettes on a stage. By the 1880s, new and independent types of Salons to show art had become established. One of them was the “Salon des Indépendants,” where this work was first shown in 1886. The comments by critics were mostly negative. One critic wrote that Seurat was “hiding reality under a swarm of fleas [i.e., the dots]”; others talked about “Assyrian figures” in reference to the repetitive profile poses. In fact, Seurat was an academically trained artist. He had studied under the academic painter Henri Lehmann, who had been a pupil of Ingres at the École des Beaux-Arts. Seurat also admired the academic painter Puvis de Chavannes’s frieze-like arrangement of figures, which we see reflected in his own work.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–1886, oil on canvas

Post-Impressionism: Gauguin and Van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin are also Post-Impressionist artists (in the sense that they chronologically come after Impressionism), but in truth one can look at them in a variety of ways. For example, one can think of them as Symbolist artists. Symbolism, the last art movement of the 19th century, emphasized mysteries, world religions, and non-European cultures. It was also profoundly anti-rational. But one can also think of the two artists, who at one time worked together, as precursors to Expressionism, in the sense that they used broad brushwork and color to express inner emotional states. (Many art movements of the 20th century touched on Expressionism in some form; the most basic definition of expressionism is that it can be used to reflect inner emotions through color, brushstrokes or other artistic means.) But most importantly, van Gogh and Gauguin were two great individualist artists who defined modernism and the feelings of alienation it encapsulates. Their art is filled with emotional responses, fantasies, dreams, and even references to madness.

Vincent VAN GOGH (1853–1890)

Van Gogh was of Dutch origin. Before becoming a painter, he had worked as an art dealer and as an evangelist/social worker in an impoverished mining district in Belgium called the Borinage. He is often portrayed as a “mad” artist, but his “madness” may in fact have been epilepsy. By the standards of the 19th century, van Gogh came to art late in his life. He turned to painting at 27 as a career of last resort. At this time, he had returned to his parents’ home after he had failed in art school. His father was a Protestant pastor in the town of Nuenen. Since van Gogh had startled the local townspeople before, he was told to only make sketches in his father’s presbytery. The mood is dark and depressing in this sketch, as was Vincent’s at the time.

Vincent van Gogh, The Garden of the Presbytery at Nuenen, Winter, 1884, pen and pencil drawing

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887 Gauguin, Self-portrait, 1888

Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, 1885, oil on canvas

Van Gogh: The Late Years

Starry Night is perhaps one of van Gogh’s most famous pictures, which he painted shortly before his suicide. The composition is pervaded by supernatural qualities, as spiral movements roll across the sky from left to right, stars seem to explode, and cypresses shoot like flames into the air. In July 1890, van Gogh shot himself in a wheat field near Auvers-sur-Oise, where he had sought help in the hospital of a progressive psychiatrist named Dr. Gachet (he even did a number of portraits of Dr. Gachet). In a last unfinished letter to his brother Theo, the artist wrote, “Really, we can speak only through our paintings. In my own work I am risking my life; and half my reason has been lost in it.”

- The greatest Dutch artist since the Baroque period

- Only painted the last 10 years of his life

- Began with the dark Dutch palette but lightened up when he went to France

- There could be no Vincent without Theo, who died right after Vincent

- We know so much about him because he wrote many letters, mostly to Theo

- He collected Japanese woodblock prints

- Starry Night, 1889, is his most famous painting

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas

Watch the following video on van Gogh’s Starry Night. As you are watching, take notes:

- What were some of the technological and cultural developments that were taking place during this time? How did these events influence the style of Post-Impressionists like Gauguin and van Gogh?

- Describe the formal qualities of van Gogh’s style.

- How did van Gogh’s inner mental state influence his work?

Gustav KLIMT (1862–1918)

- Leader and first president of the Vienna Secession, a group of artist that provided a forum for diverse styles that shared the rejection of Academic naturalism, even though Klimt was an established painter in the Academic tradition

- Trained as a goldsmith

- The Kiss, 1908

The Kiss, 1907–8, oil on canvas Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), which sold for a record $135 million in 2006

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso was probably the most influential artist of the 20th century. Picasso was a native of Spain but active for most of his life in France. He invented, together with Braque, a movement called Cubism. Cubism departs from Renaissance perspective and offers an escape from the mandate to create faithful representations of physical reality. Picasso had a long and prolific career, which can be divided into several specific periods. At the beginning of Picasso’s mature art are the Blue Period (1901–1904) and the Rose Period (1905–1906). These were moments of poverty, depression, and a bohemian lifestyle for the young Picasso in Paris. Later on, he would be quite wealthy as the fame and value of his art grew, but his sympathies were always with socialist and anarchist politics. Some but not all of his art is politically engaged. Picasso once proclaimed, “No, the purpose of painting is not to decorate apartments. It’s a weapon for the attack and defense against the enemy.” Decorating apartments with art was seen as a bourgeois occupation. Although this statement was aimed against an art dealer, Picasso did not like the bourgeoisie and its conventional attitudes toward art.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, oil on canvas

Picasso and Braque: Cubism

Picasso and Braque: Analytical Cubism

Shortly after completing the Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso became good friends with a fellow painter named Georges Braque. Together, they would go on to invent Cubism, the style and art movement for which Picasso is best known. The close collaboration between Braque and Picasso unfolded between 1909 and 1914, after which point it was cut short by Braque’s being drafted to fight in World War I, where he received a serious head injury that changed his personality. We can distinguish two “flavors” of Cubism: “Analytical” and “Synthetic” Cubism. Ma Jolie belongs to “Analytical Cubism,” which refers to straightforward painting without the added, extraneous materials that define “Synthetic Cubism.” In “Analytical Cubism,” physical reality and space are analyzed in terms of their planar components. Objects in this space subsist as fragments of their physical appearance; any remnants of three-dimensional, physical space are now completely abandoned. An example would be the barely visible fragments of the female figure in this composition (for example, the hand, in the lower right corner, covering the sound hole of a guitar) to which the title alludes.

Watch the following video, “Pablo Picasso and the New Language of Cubism.” As you are watching, take notes: https://youtu.be/GRTsMJNcHFw

- How does this new style reject the traditional modes of representation codified during the Renaissance?

- What is this “new language” of representation in Cubism?

Picasso’s Guernica

Guernica stands out as Picasso’s uncontested masterwork. An eminently political statement, it was the largest canvas he ever created. The subject deals with the Spanish civil war of the 1930s, which pitched the left-wing republican government and the Fascists under General Franco; the picture was painted at a moment when the Fascists won out. The work pre-dates the Second World War but anticipates many of the political struggles that will eventually trigger the bigger war. Guernica was conceived as a giant indictment of the brutality of the Fascist government of Spain. Guernica was the capital of the Basque region in Spain, to which the Republican government had granted autonomy. The nationalist agenda of General Franco’s Fascist government saw Basque autonomy as a challenge to their authority and ordered the bombing of the Basque capital, Guernica, through the air force of allied Nazi Germany. Guernica was completely destroyed, resulting in the senseless bloodshed of the civilian population depicted by Picasso. Since Picasso read about the massacre in the papers, he recreated a newsprint-like structure for part of the background. Guernica is a universal artistic statement against all war and for peace, which Picasso rendered in terms of private symbolism. The bull, for example, stands for brutality and darkness and hence for the Fascists. The woman who fearfully sticks out her head from a house while holding a candle in her hand is supposed to embody the conscience of horrified humanity. On the left, there is a crying woman with a dead child, mangled corpses of the dead, a rearing horse, and a man about to burn on the far right; they all represent horror and disgust with the brutality of the Fascist rule. Picasso deliberately kept the painting monochrome to signal the tragic aspects of these events. Stylistically, Guernica is a hybrid between Cubism and Surrealism, which Picasso infused with his own pseudo-archaic symbolism. After the defeat of Fascism in World War II, Picasso became world-famous for this picture, which was kept for many years in New York until, as per Picasso’s will, it was returned to Spain after the fall of Franco’s regime.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas

Duchamp: Invention of the “Readymade”

Duchamp’s most consequential activity in the art world was the invention of the “readymade,” by which he meant pre-fabricated, mass-produced items that become works of art by virtue of an artist’s act of designating them as such. A pile of bricks, placed in a museum, can become an artwork, if there is an artist declaring them such. Duchamp helped bring about the advent of conceptual art, which holds that it is the idea that matters for art, not the final product. In the final analysis, thus, the notion of art itself becomes meaningless.

Fountain was one of Duchamp’s first “readymades.” As should be obvious, Fountain was a urinal turned upside down. Submitted under the name of the fictitious artist “R. Mutt” to the juried “Exhibition of Independent Artists” in New York in 1917, the object, of course, was rejected by the jury and was never returned to the artist. Over the years, Duchamp purchased more urinals, signed them, and designated them as authenticated replacements for the “original” Fountain. Duchamp’s act was meant as a deliberate Dadaist insult at the art establishment. What mattered was the thought and the gesture, not the crafting of the Fountain. But beyond the obvious pun or insult, Duchamp also wanted to draw our attention to the inherent beauty of such a trivial object.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 (reconstruction 1950), ready-made glazed sanitary china with black paint

Watch the following video on Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. As you are watching, take notes on the following topics and questions: https://youtu.be/FmjSUyyc-3M

- How was this work received?

- What is the artist’s role in “creating” a readymade? How can the artist “transform” an everyday object?

- How did this work challenge the notions of traditional art?

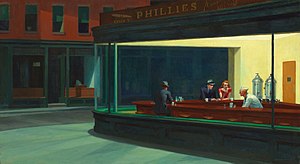

Hopper: American Melancholia

Edward Hopper defined American art between the two world wars like no other. With him we find the first evidence of a return to figurative subject matter. Hopper captured the essence of the American psyche during the Great Depression and World War II. He was a master of introspection, dealing with themes of isolation and alienation in mass society. Nighthawks is a late-night scene of a diner in one of America’s big cities. There is little communication between the guests and the barman. Open space and a sense of isolation are prevalent throughout the work, as the scene is defined more by absence than by presence.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas

Pop Art

Modernism in Crisis

After Abstract Expressionism and Post-Painterly Abstraction, the project of the avant-garde moved directly from the ultimate fulfillment of its promise to a state of crisis. How could one further purify art from the burden of history if it is already purist to the extreme? How could one further abstraction if one already painted the most abstract pictures conceivable? The lack of answers to these questions defined the moment of crisis in the development of modernism. Pop Art also came to epitomize this moment of crisis because it signaled a return to representational art. Clement Greenberg was adamantly opposed to Pop Art because of its contents (not surprisingly, since he advocated “purist” abstraction). The rise of Pop Art in the late 1950s and 1960s coincided with the beginnings of the post-modern debate and the terminal decline of modernism.

Abstract Art vs. Pop Art

One can summarize the clash between abstract art and Pop Art in the following terms:

Abstract Art

- Abstract

- Intellectual

- Maintains values of high or elite culture

- Existentialist (influenced by writings of J.-P. Sartre), philosophical

- Theoretical

Pop Art

- Blatantly figurative

- Popular

- Lowbrow culture, deliberately ephemeral

- Deliberately superficial

- Empirical, based on direct observation

Pop Art has a very strong socio-economic (instead of philosophical) dimension. The emergence of mass consumer society was a phenomenon of post-World War II America. A key idea in this context is that of obsolescence, or the pre-calculated life of consumer goods in order to stimulate demand. Consumer society constitutes the exception to the rule in the history of human civilization, as the bottleneck in consumption was no longer in supply, but in demand. Hence, we find the need for the packaging of food and toiletry items; mass advertisements, and expendable appliances—all measures meant to make consumption more enticing. According to some urban anthropologists, by the 1950s, Manhattan alone started to throw away more manufactured goods in a week than 18th-century France produced in a year. For Americans, consumption meant (and still often means) disposability, not durability; replacement, not maintenance. The rise of Pop Art coincided with the invention and spread of TV, which became another key contributor to the topography of consumer culture, because it allowed producers of merchandise to bombard consumers with broadcast TV messages. Pop Art thrived in this climate of a fully developed capitalist consumer society.

Johns: American Pop Art in the 1950s

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns belonged to the first generation of American Pop artists. Johns was a window decorator from Atlanta, living in Manhattan, who attained sudden fame in 1958, when he was given a show at the influential Leo Castelli Gallery. An Italian immigrant art dealer, Castelli is famous for promoting Pop Art at a moment when nobody realized the importance of the art movement. Johns came to subscribe to Rauschenberg’s ideas about Pop Art during the mid-1950s. His objects rely principally on the play between sign and art and first came into prominence with his series of flag paintings. One can compare his artistic strategy with that of Magritte’s Treachery of Images. These are not real flags but paintings of flags. In this example, Johns used encaustic—that is, painting with hot wax, a technique that was known since ancient Egypt and classical antiquity. As a nod to consumer culture, he embedded newspaper fragments in the hot wax. The result is a paradoxical combination of materials. Johns chose the American flag for its iconic immediacy—it is instantly recognized by everyone, everywhere.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954, encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood

Warhol: The King of Pop

A second-generation Pop artist, Andy Warhol became the figurehead of the movement in the 1960s. Warhol was not only a painter but also a filmmaker and a socialite. He is famous for his quotes, such as the “15 minutes of fame” to which everybody should be entitled, or “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There is nothing behind it.” Warhol was the son of working-class Czech immigrants and graduated as a graphic designer from Carnegie Tech in 1949. He began work as a commercial artist in New York shortly thereafter, creating designs for shop windows or delicate drawings of shoes for the shopping bags of Miller and Co., which brought him acclaim. In 1959, Warhol was the highest-paid commercial artist in the city, earning nearly $65,000/year. However, he was not yet a fine artist, a role he assumed only in the early 1960s. Mass production and repetitions of basic design principles are the cornerstones of Warhol’s art. The originality of the artist’s hand was of no interest to him: “Somebody should do all my paintings for me. The reason I am painting this way is because I want to be a machine. […] I think it would be terrific if everyone was alike.” Indeed, almost all of Warhol’s paintings were executed by assistants. He was running a large workshop. Warhol was obsessed with celebrities and product packaging, which constitute the two recurrent themes of his art. All products he depicted were standardized and universally accessible (Coke bottles, Campbell soup cans, etc.). In June 1863, a feminist groupie walked into the “Factory” and shot Warhol; he was pronounced dead on arrival in the hospital but recovered against all odds. Thereafter, death became an important theme in his art. Warhol died in 1987 from complications of this attempt at his life.