2 Chapter 2: Mediums in Visual Art

Chapter 2: Mediums in Art

Pigment = The colored powders made from organic or inorganic substances. Means to paint and is the basis of color. Ex. Plant or animal matter, semi-precious stones, minerals, etc. Used not only in paint, but also colored drawing supplies like pastels, crayons, colored pencils.

Binder = The liquid that adheres the pigment to a surface. Ex. Blood, water, oil, plaster, etc. The surface can be canvas, paper, wood, stone, etc.

Watch the following video, “The Value of Art: Medium from Sotheby’s.” As you are viewing the video, consider the following questions:

- What are the more traditional mediums?

- How has medium changed in modern and contemporary art?

We will review some of the most common media used in the creation of artworks: drawing, painting, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, architecture, performance art, dance, and music (among others).

Subheading: Drawings

Traditionally, artists were first taught how to draw before painting a picture or sculpting a sculpture. Ever since the Renaissance, in the Western (academic) artistic tradition, drawing skills were the cornerstone of artistic practice. As conventional wisdom has it, an outstanding draftsman promises to become a great artist. Drawings allow artists to collect and record ideas (for example, in sketchbooks), to try out proportions, and to visualize ideas (preparatory drawings). For many artists, preparatory drawings are used to work out composition, form, or other elements before completing the final work of art, which is often completed in a different medium, such as oil or bronze. Preparatory drawings may be “studies” of figures, objects, or landscapes drawn from life. Sometimes, however, drawings can be an end in themselves. The Italian word “disegno” is a distant relative of the English expression “design.”

Drawings use a variety of media, including pen, pencil, ink, watercolor, gouache, charcoal, pastel, etc., which are “supported” or applied to a surface, such as a piece of paper, cloth, wall, and so on.

Take a look at these two examples of drawings. Although they are of a similar medium —pen and ink—what are some of the distinct visual differences you notice?

Leonardo da Vinci, A Man Tricked by Gypsies, ca. 1493, pen and ink drawing

Vincent van Gogh, The Fountain in the Hospital Garden, 1889, pen and ink drawing

You may have noticed that one of the major differences between these two works is the distinction in the quality of the line work. A line is defined as the extension of the dot that can indicate direction, motion (especially waves), can indicate boundaries of shapes and spaces, and can imply volumes of solid masses. Line involves the delineation of form—as seen in the contours of the men’s faces in the da Vinci drawing—or it can be used to create tonal variations, shading, hatching, and crosshatching, as seen in the van Gogh drawing.

Watch the following short video on how line is used in art. Take note of the various ways in which line is used to achieve different results.

Subheading: Pastel Drawings

Pastels present a problem apart in the drawing “family.” Pastel is a chalk-like, friable (easily crumbled) medium, which often requires colored paper to make full use of its visual effects. Once completed, the pastel drawing must be “fixed” using some sort of sticking spray to prevent the pigment from detaching from the support. Pastels were a very popular medium in eighteenth-century Rococo art because of its soft touch and muted colors. Later on, Impressionist artists, such as Edgar Degas, also embraced the medium for its ability to capture colorful impressions quickly and spontaneously. It is nearly impossible to correct or alter a pastel drawing later on.

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of a Girl with a Bussolà, 1725–1730, pastel on paper

Edgar Degas, Le petit déjeuner après le bain (Jeune femme s’essuyant), ca. 1894, pastel on paper

Subheading: Paintings

Painting is based on a bewildering range of types of paint and types of support, including, but not limited to, oil, fresco, tempera, watercolor, encaustic (hot wax), and acrylics.

Common types of support (i.e., the surface upon which the paint is applied) include canvas, wood, board, copper, paper, etc.

When we identify a painting, we want to include the type of paint and its support in its description. For example, oil on canvas, tempera on board, oil on paper, oil on copper, etc.

Review the following presentation detailing the most common types of paint, including their history and formal characteristics.

All colors and paints consist of two or three ingredients:

- Powdered pigment—(see examples above) Made of ground up plant or animal matter, semi-precious stones, minerals, etc.

- A binder is a liquid that sticks the powder to a surface. It can be wax, water, oil, plaster, glue, etc.

Encaustic: Pigment-suspended Hot Wax Painting

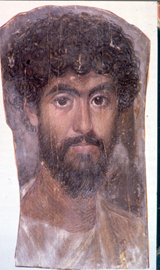

1. Mummy Portrait of a Man, Faiyum (Egypt), ca. A.D. 160–170, encaustic painting on wood (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo)

2. Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954, encaustic, oil and collage on fabric mounted on plywood

Encaustic paint has as its ingredients:

- Powdered pigment

- Binder = beeswax

- Thinner = no substance thins encaustic paint, instead, heat is the thinner

- Used since ancient times (think of mummy portraits and ancient Egypt)

Fresco Painting (Buon Fresco) is pigment suspended in plaster.

Fresco paint has as its ingredients:

- Powdered pigment

- Binder = lime in plaster

- Thinner = water

- Used since ancient times (in some Egyptian tombs that are at least 5,000 years old!)

- Name comes from the Italian word for “fresh”; True Fresco must be painted on fresh, wet plaster

- Color pigments are diluted in water, then applied to a freshly plastered wall

- Pigments soak deep into the plaster while it is still wet; lime in plaster becomes a binder

- Rapid execution, working in segments, is necessary; technique best for covering large wall spaces

Tempera paint (traditionally, egg tempera) has as its ingredients:

- Powdered pigment

- Binder = egg yolk

- Thinner = water

- Color pigments mixed with egg yolk

- About as old as the encaustic technique

The Annunciation, Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, Tempera on gold, Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

For all intents and purposes, tempera painting “behaves” like a watercolor. Pioneered by Flemish painters (Flanders = Northern Belgium).

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child, ca. 1440–1445, tempera on board

Oil on Canvas

Oil paint has as its ingredients:

- Powdered pigment

- Binder = linseed oil

- Thinner = turpentine (a sap from a pine tree)

First used in the 15th century (the Renaissance). The first artist to explore technique was Flemish painter Jan van Eyck, but the Italians perfected it and used it extensively. Texture of canvas and consistency of paint can greatly influence the character of a painting.

Watercolor/Gouache

Ingredients for transparent watercolor are:

- Powdered pigment

- Binder = gum arabic

- Thinner = water

- Opaque watercolor (Gouache) adds: Chalk dust

- The pioneer in watercolor painting was Albrecht Dürer, a Northern Renaissance artist

Albrecht Dürer, The Great Piece of Turf, 1503, watercolor.

Winslow Homer, Sloop, Nassau, 1899, watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper.

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash, 1967, acrylic on canvas

The Pizz, The Teenage Detox Hospital, 1999, acrylic on canvas

- Relatively recent invention (second half of 20th century)

- Pigments suspended in acrylic polymer medium

- Transparent “films” of color

- Dries fast

- High degree of color intensity

Subheading: Mosaic

Mosaics are made up of small pieces of colored glass, stone, or ceramic tile called tessera that are embedded in a “bed” (background material), such as mortar or plaster. The tessera can be combined to create complex images, which look “pixelated” in photographic reproduction. Mosaics can be found on walls and on floors; they have been used at least since the days of ancient Greece. Many mosaics can also be found in early Christian churches.

Mosaic of Empress Theodora and Attendants, ca. 547, Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic. By Petar Milošević – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60402597

Mosaic of Empress Theodora and Attendants, ca. 547, Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic. By Petar Milošević – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60402597

Detail of mosaic on the left showing Empress Theodora. This artwork was created 2 months before her death from breast cancer.

Subheading: Sculpture

Traditionally, there are two distinctive approaches to sculptural techniques, one is subtractive (typically pertains to media like stone, wood, or ivory) and the other additive (typically applies to media like clay, bronze, plaster, or wax).

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Awakening Slave, 1530–1534, marble, for the unfinished tomb of Pope Julius II.

This is an example of a subtractive approach to sculpture. You can imagine how Michelangelo started out with a marble block, from which he chiseled away until the figure began to emerge.

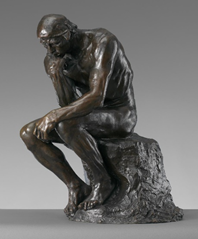

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker (Le Penseur), design ca. 1880 (cast ca. 1910), bronze

This is an example of an additive approach to sculpture. Rodin started out by building a positive wax model of The Thinker, which was turned into a negative investment mold from which multiple bronze copies could be cast. The lost-wax casting method is explained in detail below.

Assessment: Take a look at this sculpture. Which sculptural approach was used?

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Bound Slave, 1513–1516, marble.

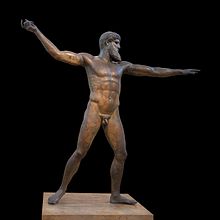

The lost-wax casting method was already known in ancient Greece (see Zeus/Poseidon, below) but proliferated greatly in late nineteenth-century France (when Rodin lived) with the advent of industrial production methods. In 1839, Achille Colas even invented a machine that allowed for scaled copies (larger or smaller) of sculptures to be industrially produced.

Zeus (or Poseidon), Bronze. 209 cm high.

Subheading: Prints and Printmaking

Prints allow the artist to create identical reproductions of the same image. They are distinct from original (one-of-a-kind) works of art. By definition, multiples are artworks that exist in multiple, identical copies, executed in media that lend themselves to reproductions, such as cast sculpture (bronzes, etc.), prints, photographs, etc. Multiples typically have a limited-edition size—that is, the number of copies (in prints, we call them impressions) from a printing plate or casting mold is limited. The edition size is often inscribed on the object. The convention for denoting editions follows this pattern: if you have a print with a (mostly manuscript annotation) 2/15, you know that it is the second impression out of a total edition of 15.

There are two major types of printing processes: relief and intaglio.

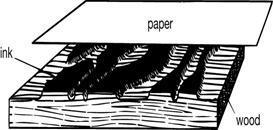

Relief processes are when printing occurs with the raised parts of the plate or those parts that have not been cut away. Examples: linoleum cuts (linocuts) or woodcuts (or wood engravings).

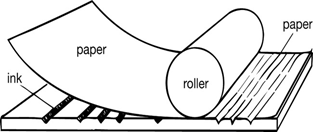

Intaglio processes (from Italian intagliare, “to cut into”) are the opposite from relief processes in that the crevices in the plate (engraved with a tool or etched with acid) hold the ink. After cutting the design of the plate, it is covered with ink; the plate is then wiped until no ink sits on the surface any longer and only the crevices of the design hold reservoirs of ink. Examples: engravings and etchings.

Schematic rendering of intaglio printing.

An intaglio print is pulled from a copper plate.

Lithography

Lithography is a printmaking technique that uses litho crayons on a fine-grained Bavarian limestone (see images below). Gum arabic and acid serve as fixative. The artist applies a design directly onto the stone with the crayons. The stone is then wetted and greasy ink is applied, which is repelled by the water in the blank areas. Physically, lithography relies on the physical quality that water and oil do not mix. The technique allows one “to print drawings.” Most non-specialists would consider lithographs as drawings, as it takes a trained eye to notice the difference. Note: “Lithography” describes the printmaking technique; a “lithograph” is print produced by means of the lithographic process.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin Rouge, ca. 1891. A 19th-century lithographer, Toulouse-Lautrec executed lithographic posters for Parisian night clubs in the Art Nouveau style.