19 Chapter 19: Dance History and Styles

Learning Objectives

- Explain the function of court dance and the development of ballet.

- Summarize the development of ballet from its professionalization through Romantic, Classical, Avant-Garde, Neoclassical, and Contemporary Ballet.

- Associate major ballet milestones with the works and choreographers responsible.

“Nothing resembles a dream more than a ballet, and it is this which explains the singular pleasure that one receives from these apparently frivolous representations. One enjoys, while awake, the phenomenon that nocturnal fantasy traces on the canvas of sleep; an entire world of chimeras moves before you.”

—Theophile Gautier, French poet

What Is Ballet?

Ballet is the epitome of classical dance in Western cultures. Classical dance forms are structured, and stylized techniques developed and evolved throughout centuries requiring rigorous formal training. Ballet originated with the nobility in the Renaissance courts of Europe. The dance form was closely associated with appropriate behavior and etiquette. Eventually, ballet became a professional vocation as it became a popular form of entertainment for the new middle-class to enjoy. Ballet spread throughout the world as dance masters refined their craft and handed their methods down from generation to generation. Over 500 years, it has developed and changed. Dancers and choreographers worldwide have contributed new vocabulary and styles, yet ballet’s essence remains the same.

Ballet Characteristics

Codified Technique

Ballet is a codified dance form ordered systematically and has set movements associated with specific terminology. Ballet is a rigorous art and requires extensive training to perform the technique correctly. The first ballet creators’ principles have survived intact, but different regional and artistic styles have emerged over the centuries. Ballet classes follow a standard structure for progression and are composed of two sections.

The first part of ballet class typically begins with a warm-up at the barre. The barre is a stationary handrail that dancers hold while working on balance, allowing them to focus on placement, alignment, and coordination. The second half of the ballet class is performed in the center without a barre. Dancers use the entire room to increase their spatial awareness and perform elevated and dynamic movements.

Alignment and Turnout

Ballet emphasizes the lengthening of the spine and the use of turnout, an outward rotation of the legs in the hip socket. This serves both to create an aesthetically pleasing line and increase mobility.

Foot Articulation

Ballet demands a strong articulated foot to perform demanding movements and create an elongated line.

Pointe shoes, a ballet staple, add to the illusion of weightlessness and flight. They are constructed with a hard, flat box to enable dance on the tips of the toes; it is a technique called en pointe that requires years of training and dedication to develop the needed strength in the feet, ankles, calves, and legs.

Elevated Movement

Traditionally, ballet favors a light quality, called ballon, with elevated movements. Dancers seem to overcome gravity effortlessly and achieve great height in their leaps and jumps.

Pantomime and Storytelling

Ballet can tell a story without words through a language of gestures called pantomime. Some movements are easily understood or have simple body language, but more abstract concepts are given specific gestures of their own to convey meaning. The facial expressions, the musical phrasing, and dynamics all play a role in communicating the story. Pantomime developed in ballet’s Romantic period and was further incorporated during the Classical era.

Watch This

The Royal Ballet dancers demonstrate and decode ballet pantomime for Swan Lake. David Pickering addresses the audience in the basics of pantomime, and audience members mimic the movement. In the second part of the clip, principal dancers Marianele Nunez and Thiago Soares reenact Act 2 as David Pickering narrates the pantomime.

Court Dance: Italy and France

In medieval Italy, an early pantomime version featured a single performer portraying all the story characters through gestures and dance. A narrator previewed the story to come, and musicians accompanied the pantomime. Pantomimes were quite popular, but they were sometimes over-the-top in their efforts to be comedic, often resulting in lewd and graphic reenactments. Dance was a part of everyday life. Peasants danced at street fairs, and guild members danced at festivals, but it was in the royal courts that ballet had its genesis.

European Renaissance: Ballet de Cour

Catherine de’ Medici

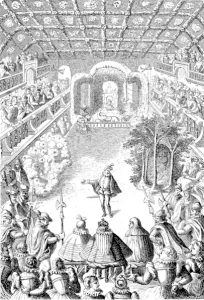

Catherine de’ Medici, a wealthy noblewoman of Florence, Italy, married the heir to the French throne, King Henri II. In 1581, she went to Paris for a royal wedding accompanied by Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx, a dance teacher and choreographer. Catherine de’ Medici commissioned Beaujoyeulx to create Ballet Comique de la Reine in celebration of the wedding, and it became widely recognized as the first court ballet. The ballet de cour featured independent acts of dancing, music, and poetry unified by overarching themes from Greco-Roman mythology. The ballet included references to court characters and intrigues. After the Ballet Comique de la Reine production, a booklet was published with libretto telling the ballet’s story. It became the model for ballets produced in other European courts, making France the recognized leader in ballet.

King Louis XIV

During King Louis XIV’s reign, France was a mighty nation. King Louis XIV kept nobility close at hand by moving his court and government to the Palace of Versailles, where he could maintain his power. At court, it was necessary to excel in fencing, dance, and etiquette. Nobility vied for an elevated position in court, as one’s abilities in the finer arts reflected success in politics.

King Louis XIV was a great patron of the arts and vigorously trained in ballet. He performed in several ballet productions. His most memorable role was Apollo, gaining the title the “Sun King” from “Le Ballet de la Nuit,” translated to “The Ballet of the Night.”

Louis XIV’s love of dance inspired him to charter the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse, headed by his old dance teacher Pierre Beauchamps and thirteen of the finest dance masters from his court. In this way, the king assured that “la danse classique”—that is to say, “ballet”—would survive and develop. The danse d’ecole provided rigorous training to transition from amateur performance to seasoned professionals. This also opened the door for non-nobility to pursue ballet professionally. For the first time, women were also allowed to train in ballet. Women were only allowed to participate in court social dances until this point. Men performers took on all the roles in court ballets, wearing masks to dance the roles of women.

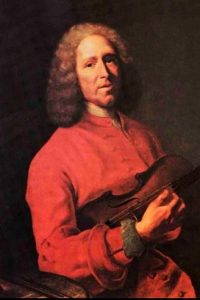

Transitioning from the ballet de cour, dances of the Renaissance ballroom grew into the ballet a entrée, a series of independent episodes linked by a common theme. Early productions of the academy featured the opera-ballet, a hybrid art form of music and dance. Jean-Philippe Rameau served as both composer and choreographer for many early opera-ballets.

At this time, there was a differentiation of characters that dancers assumed. These roles were generally categorized as:

- danse noble: regal presentation suitable for roles of royalty

- demi-charactere: lively, everyday people; “the girl next door”

- comique: exaggerated, caricatured characters

Some significant developments aided in the progression of ballet as an art form at the Académie Royale de Musique et Danse. Pierre Beauchamps significantly contributed to ballet by developing the five basic positions of the feet used in ballet technique. He also laid the foundation for a notation system to record dances. Raoul Auger Feuillet refined the notation and published it in 1700; then, in 1706, John Weaver translated it into English, making it globally accessible.

Watch This

In this split-screen, Feuillet’s dance notation is shown on the left side while dancers perform the Baroque dances on the right side.

The Académie Royale de Musique et Danse was the place to train classical dancers. Dancers and dance masters alike traveled to the great centers of Europe, bringing French ballet to the continent. Today’s Paris Opera Ballet is the direct descendant of the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse.

Watch This

This TED-Ed animated video clip summarizes the origins of ballet.

Dance in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that emphasized freedom of expression and the eradication of religious authority. These ideas caused criticism among philosophers who believed art forms should speak to meaningful human expression rather than ornamental art forms.

Jean-Georges Noverre (1727–1810)

Ballet master and choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre challenged ballet traditions and made ballets more expressive. In his famous writings, Letters on Dancing and Ballet, Noverre rejected dance traditions at the Paris Opera Ballet and helped transform ballet into a medium for storytelling. The masks that dancers traditionally wore were stripped away to show dramatic facial expressions and convey meaning within ballets. Pantomime helped tell the story of the ballet. In addition, plots became logically developed with unifying themes, integrating theatrical elements. From Noverre’s concepts, ballet d’action emerged.

Carlo Blasis (1797–1878)

Carlo Blasis was particularly influential in shaping the vocabulary and structure of ballet techniques. He invented the “attitude” position commonly used in ballet from the inspiration of Giambologna’s sculpture of Mercury. He published two major treatises on the execution of ballet, the most notable being “An Elementary Treatise upon the Theory and Practice of the Art of Dancing.” Blasis taught primarily at LaScala in Milan, where he was responsible for educating many Romantic-era teachers and dancers.

Costume Changes

During the Renaissance, men and women wore elaborate clothing. Women wore laced-up corsets around the torso and panniers (a series of side hoops) fastened around the waist to extend the width of the skirts. Men wore breeches and heeled shoes. The upper body was bound by bulky clothing and primarily emphasized footwork. By the 18th century, there were changes in costuming. Two dancers helped revolutionize costumes.

Marie Sallé (1707–1756)

Marie Sallé was a famous dancer at the Paris Opera, celebrated for her dramatic expression. Her natural approach to pantomime storytelling influenced Noverre. She traded the elaborate clothing that was fashionable at the time to match the subject of the choreography. In her self-choreographed ballet Pygmalion, she wore a less restrictive costume, wearing a simple draped Grecian-style dress and soft slippers. This allowed for less restricted movement and expression.

Marie Camargo (1710–1770)

Marie Camargo, a contemporary of Sallé, exemplified virtuosity and flamboyance in her dancing. She shortened her skirt to just above the ankles to make her impressive fancy footwork visible. She also removed the heels from her shoes, creating flat-soled slippers. This allowed her to execute jumps and leaps that were previously considered male steps.

Check Your Understanding

Romantic Ballet

From France and the royal academy, dance masters brought ballet to the other courts of Europe. These professional teachers and choreographers attended London, Vienna, Milan, and Copenhagen, where the monarchs supported ballet. During the 18th century, the French Revolution ended the French monarchy, and Europe saw political and social changes that profoundly affected ballet. By the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution resulted in middle-class people working in factories. Art shifted from glorifying the nobility to emphasizing the ordinary person.

The Romantic era of ballet reflected this pivotal time. Ballets had now become ballet d’action, ballets that tell a story. The Romantic era was a time of fantasy, etherealism, supernaturalism, and exoticism. Artistic themes included man versus nature, good versus evil, and society versus the supernatural. The dancers appeared as humans and mythical creatures like sylphs, wilis, shades, and naiads. Women were the stars of the ballets, and men took on supporting roles. Choreography now included pointework, pantomime, and the illusion of floating. Romantic ballets most often appeared as two acts. The first act would be set in the real world, and dancers would portray humans. In contrast, the second act was set in a spiritual realm and often would include a tragic end.

Theater Special Effects

The opera houses featured stages with prosceniums, a stage with a frame or arch. The shift of performance venues had a significant effect on ballet in the following ways:

- In ballrooms, geometric floor patterns were appreciated by audiences who sat above. The audience’s perspective changed to a frontal view with the introduction of the proscenium stage, and the body became the composition’s focus.

- Turned-out legs were emphasized, allowing dancers to travel side-to-side while still facing the audience. This required dancers to have greater skill and technique.

- The proscenium stage separated the audience and performers, transitioning from its social function to theatrical entertainment.

- Curtains allowed for changes in scenery.

- The flickering of the gas lights in the theaters gave a supernatural look to the dancing on the stage.

- Theaters also enabled rigging to carry the dancers into the air, giving the illusion of flying.

The stagecraft of the time lent itself to creating the scenes that choreographer Filippo Taglioni would use in his ballets.

La Sylphide

In 1824, ballet master Filippo Taglioni (1777–1871) choreographed La Sylphide. His daughter Marie portrayed the sylphide, an ethereal, spirit-like character. Marie Taglioni (1804–1884) wore a white romantic tutu with a bell-shaped skirt that reached below her knees, creating the effect of flight and weightlessness. Taglioni also removed the heels from her slippers and rose to the tips of her toes as she danced to give her movement a floating and ethereal quality. Taglioni is recognized as one of the first dancers to perform en pointe.

La Sylphide features a corps de ballet, a group of dancers working in unison to create dance patterns. Because the corps de ballet is dressed in white romantic tutus (as is the norm with sylphs, fairies, wilis, and other creatures that populate the worlds of Romantic ballet), La Sylphide is known as a ballet blanc.

Watch This

Watch this video of the Royal Scottish Ballet that describes and shows excerpts from La Sylphide.

Auguste Bournonville (1805–1879)

Auguste Bournonville, a French-trained dancer, served the Royal Danish Ballet as a choreographer and director. Four years after the original La Sylphide production, Bournonville re-choreographed the ballet. Bournonville’s dances feature speed, elevation, and beats where the legs “flutter” in the air. He also expanded the lexicon of male dancing by adding ballon for men and stylized movements for women that portrayed them as sweet and charming. Bournonville created many dances for the Danish ballet, and the company has preserved his choreography through the centuries.

Watch This

The Bournonville variation from Napoli demonstrates movements of elevation.

Giselle

Giselle is a ballet masterwork that is still performed worldwide. It is inspired by the literary works of Heine and Hugo that referenced the supernatural wilis. Giselle was choreographed by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot and composed by Adolphe Adam. It is almost a template for the traditional Romantic ballets. Act 1 is set in a village, and act 2 is in a graveyard, an otherworldly place populated by the ghosts of young girls who died before their wedding day, willis. Giselle falls in love with a young man, Albrecht, who pretends to be a local but is really a nobleman. Distraught by his deception, she dies from grief. When Albrecht visits her grave, the wilis conspire to dance him to death. Giselle, now a wili herself, intervenes to save him.

Coppélia

Not all Romantic era ballets were tragic and supernatural. Arthur St. Léon created the great comedic ballet Coppélia: The Girl with the Enamel Eyes. The ballet is based on a tale by E. T. A. Hoffman. It tells the story of a village boy, Franz, enamored by the girl Coppélia. Unbeknownst to him, she is an automaton. His jealous girlfriend Swanilda discovers the deception created by the doll’s creator, and when the old toymaker tries to animate his doll with magic, she takes the doll’s place and pretends to come to life. The characters’ antics were great hits with audiences, and the ballet remains popular today.

Classical Ballet: Imperial Russia

About the time King Louis XIV was sponsoring the creation of ballet in his court, Peter the Great became tsar of Russia (1682–1725). He embraced science and Western social ideas in an effort to bring “the Enlightenment” to Russia. Peter built the imperial city of St. Petersburg and established his court there. His successor, Empress Anna, retained Jean-Baptiste Lande in 1738 to establish a ballet school at the military academy she had established. This school became the home of the Mariinsky Ballet. The Bolshoi Ballet was a rival school and company later established in Moscow.

Following Lande’s lengthy directorship in St Petersburg, many of Europe’s most important ballet masters and choreographers took a turn at the helm in creating dance in Russia, including Jules Perrot, Filippo Taglioni, and Arthur St Léon.

Marius Petipa (1818–1910)

Marius Petipa was the most influential choreographer of this era, known as “The Father of Classical Ballet.” A dancer from a family of French ballet dancers, he moved to St. Petersburg as a minor choreographer. He rose to great importance in Russian ballet as the director and choreographer of the Mariinsky Ballet for nearly sixty years (1847–1903). He created over sixty ballets in his career, restaging a number of the great Romantic-era ballets (much of the existing choreography of ballets like Giselle and Coppélia is the work of Marius Petipa’s restaging). Petipa also created new original ballets, beginning with The Pharaoh’s Daughter, a five-act ballet complete with an underwater scene and livestock onstage.

Characteristics of Classical Ballets

Marius Petipa is responsible for the defining characteristics of classical ballets. Petipa’s creations told stories using ballet, character dance, and choreographic structures that highlighted the most technical dancers of the company.

Classical Ballet Choreographic Structure

Petipa developed a standard choreographic structure. He used character dances, folk dances that depicted various cultures, to add variety to the performance. Unlike the Romantic ballets that consisted of two acts, classical ballets expanded to three or four acts. Many dances that had nothing to do with moving the plot forward were included in these ballets to make them longer. These extra dance numbers are called divertissements (diversions). Divertissements were often character dances. The end of the ballet usually features the grand pas de deux, a duet for the principal dancers. The grand pas de deux has four sections:

- Adagio: The principal dancers perform slow movement together that is fluid and controlled.

- Man’s Variation: Males display their technical virtuosity by performing leaps, turns, and jumps.

- Woman’s Variation: Females often perform quick footwork and turns.

- Coda: The principals dance together to display impressive movements.

Watch This

The Sleeping Beauty grand pas de deux featuring Robert Bolle and Diana Vishneva.

Contextual Connections

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed three great ballets. He was already a recognized and respected composer in Russia when Petipa asked him to compose the ballet score for The Sleeping Beauty. Petipa gave Tchaikovsky specific instructions on the music he required for the ballet. The ballet was lavishly produced and became an enormous success.

Tchaikovsky’s second ballet, The Nutcracker, was choreographed by Petipa’s choreographic assistant, Lev Ivanov (1834–1901). Ivanov worked alongside Petipa in the creation of many ballets. He created entire portions of Petipa ballets and ballets of his own.

The Nutcracker was not admired in Russia at the time—it was seen as frivolous and trivial. It was in America in the middle of the 20th century that the Nutcracker found popularity as a vehicle for local dancers in communities around the country.

The third well-known ballet Tchaikovsky composed was Swan Lake. Marius Petipa choreographed the first and third acts of the ballet—those set in the environs of Prince Siegfried, the town and ballroom, and the world of people. Lev Ivanov choreographed acts 2 and 4, the beautiful scenes set at the lake with the swans.

After the revolution of 1917, the Russian populace embraced ballet. Rather than discarding it as a symbol of the tsars, the working class adopted it as their own, and ballet became a symbol of national pride.

At the end of the 19th century, Russia was at the apex of the ballet world, and this continued well into the 20th century. The Vaganova Choreographic Institute in St Petersburg employs Russia’s finest teachers to train its dancers. The life of a ballet dancer in Russia brings privileges and opportunities that make acceptance into the school highly desirable.

Check Your Understanding

Ballet Russes: Dance and the Avant-Garde

Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929)

Sergei Diaghilev, a Russian art lover, organized the Ballet Russes in 1909. He identified ballet as the ideal vehicle to present the Russian arts to the West. Diaghilev’s troupe included some of Russia’s finest dancers and choreographers recruited from the Vaganova Institute and the Mariinsky ballet. He promoted collaborations with avant-garde composers and artists of the time. The tour to Paris extended 20 years as the Ballet Russes performed for Paris, Europe, and the Western world. The Ballet Russes introduced a new and modern form of ballet, revitalizing ballet in the West.

Michel Fokine (1880–1942)

The first choreographer of Ballet Russes was Michel Fokine. Like Jean-Georges Noverre, Fokine developed principles to reform ballet. Fokine focused on ballet’s expressiveness rather than physical prowess. He believed movement should serve a purpose to the theme, and costumes should reflect the dress of the time and setting. Fokine also stripped away pantomime in his ballets, emphasizing movement and self-expression as the catalyst for storytelling. His one-act ballet Les Sylphides was reminiscent of the earlier ballet La Sylphide in its use of the ethereal sylph. But Fokine’s ballet had no plot. A single man, a poet, dances among a group of sylphides in a ballet that evokes a dreamlike mood.

Watch This

Excerpt from Les Sylphides (ca. 1928). This black-and-white clip is some of the only footage of the company that exists. Diaghilev did not want his ballet company to be filmed because he was afraid of losing income from box office sales.

Fokine’s The Firebird was based on tales from Russian folklore. His Petrouchka told the story of a trio of puppets at a Russian street fair.

Vaslav Nijinsky (1889–1950)

Vaslav Nijinsky was a principal dancer of the company and is remembered for his astonishing gravity-defying jumps and poignant portrayals. When Fokine left the company, Nijinsky became the principal choreographer. He choreographed the Rite of Spring: Tales from Russia, Afternoon of a Faun, and Jeux. Nijinsky’s dances were controversial because the themes, movement aesthetics, and music were unconventional for the time. The Rite of Spring portrays a pagan ritual and fertility rites that left the audience in an uproar on its opening night.

Watch This

Excerpt from The Rite of Spring.

Léonide Massine (1895–1979)

Léonide Massine followed Nijinsky as a choreographer, where he expanded on Fokine’s innovations, focusing on narrative, folk dance, and character portrayals in his ballets. Parade is a one-act ballet about French and American street circuses. Pablo Picasso designed the cubist sets and costumes.

Watch This

Excerpt of Parade. The characters are introduced in three groups as they try to entice an audience into the performance. The giant cubist figures portray business promoters.

Bronislava Nijinska (1891–1972)

Bronislava Nijinska, the fourth Ballet Russes choreographer, was Vaslav’s sister and stands out as one of the few recognized women choreographers. Her ballet Les Noces, set to music by Stravinsky, was noted for its architectural qualities. She created several ballets known for being Riviera chic, portraying the carefree lifestyle of Europe’s idle rich.

Watch This

Excerpt from Le Train Bleu; you can see the costumes designed by Coco Chanel.

George Balanchine (1904–1983)

George Balanchine was the fifth and last choreographer of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. He created ten ballets for the company. The Prodigal Son is a retelling of the Bible story. Apollo shows the birth of the god Apollo and his tutoring in the arts by the three muses. Those two ballets remain in the repertory of the New York City Ballet.

Watch This

Excerpt from Balanchine’s Apollo performed by Pacific Northwest Ballet.

Watch This

This short clip features pictures and footage with commentary by Lynn Garafola, Nancy Reynolds, and Charles M. Smith.

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Original Ballet Russe

Diaghilev died in 1929, and his company disbanded with him. Two other companies emerged in its wake, the Original Ballet Russe and Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. They would hire several of the dancers of the parent company and travel Europe and the Americas throughout the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. They spread ballet around the world, and their dancers would become the next generation of dancing masters.

The Five Moons

Many American dancers found work with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Original Ballet Russe. Five exceptional Native American dancers who became ballerinas with these companies hailed from Oklahoma. Known as the Five Moons, a reference to their tribes, these women gained fame and success at the highest levels of ballet and were foundational in the development of Oklahoma dance institutions.

Maria Tallchief (Osage Nation, 1925–2013) went on to dance with the New York City Ballet. She married George Balanchine and worked with him for many years. Balanchine’s Firebird was a signature role for her.

Marjorie Tallchief (Osage Nation, 1926–2021), Maria’s sister, was known for her great versatility as a dancer. She had a successful dancing career in Europe and the States, then served as director at Dallas Civic Ballet Academy, Chicago’s City Ballet, and Harid Conservatory in Boca Raton.

Moscelyne Larkin (Peoria/Eastern Shawnee/Russian, 1925–2012) first learned ballet from her dancer mother. She starred at Radio City Music Hall and founded Tulsa Ballet Theatre with her husband.

Yvonne Chouteau (Shawnee Tribe, 1929–2016) joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo at the age of 14, where she danced many roles from the Ballet Russe repertory. She served as an artist in residence at the University of Oklahoma and founded Oklahoma City Ballet with her husband.

Rosella Hightower (Choctaw Nation, 1920–2008) danced with these major companies and with American Ballet Theatre, but she later found her work in France as director of Marseilles Opera Ballet and then Ballet de Nancy. Hightower was the first American director of the Paris Opera Ballet.

Neoclassical Ballet

Neoclassical dance utilizes traditional ballet vocabulary, but pieces are often abstract and have no narrative. Several choreographers were experimenting with the neoclassical style. Balanchine’s work is regarded as neoclassical, embracing both classical and contemporary aesthetics. Balanchine wanted the attention to be on the movement itself, highlighting the relationship between music and dancing by creating movement that mirrored the music. Balanchine also employed freedom of the upper body, moving away from the verticality of the spine for a more expressive movement that drew inspiration from vernacular jazz dance styles that became prominent.

American Ballet in the 20th Century

At the invitation of Lincoln Kirstein, George Balanchine went to New York City when the Ballet Russes ended in 1929. In 1934, they established the first ballet school in the United States, the forerunner of the School of American Ballet. It expanded into a short-lived dance company. In 1948, Balanchine established a small company that ultimately grew to become the New York City Ballet (NYCB). New York City Ballet is the resident company of Lincoln Center in NYC and one of the most recognized ballet companies in the country.

George Balanchine was a prolific choreographer with a long career. Due to his contributions to the development of ballet in the United States, Balanchine is known as “the father of American ballet.” He wanted to express modern 20th-century life and ideas to capture the spirit and athleticism of American dancers. Some of his most famous ballets include Serenade, Jewels, Stars and Stripes, and Concerto Barocco.

Watch This

Excerpt of the Rubies pas de deux from the ballet Jewels.

American Ballet Theatre (ABT)

American Ballet Theatre (ABT), a New York City Ballet contemporary, is also recognized as a premier ballet company. Its mission is to preserve the classical repertoire, commission new works, and provide educational programming.

Its directors have included Lucia Chase and Oliver Smith, Mikail Baryshnikov, and Kevin McKenzie. Hundreds of renowned choreographers have created works with ABT. Antony Tudor created intimate psychological ballets, Agnes de Mille created ballets of Americana, and Jerome Robbins produced ballets across a range of styles.

Watch This

Excerpt from Rodeo by Agnes de Mille. The dancers mimic the bowed legs of cowboys and trot about as if they are astride horses. Aaron Copland composed the music.

Ballet grew in other cities of America as well. San Francisco Ballet was founded by Adolphe Bolm, a Ballet Russes dancer. Chicago and Utah both established ballet companies early on.

Other Notable American Ballet Artists

Mid-20th Century

Jerome Robbins (1918–1998)

Jerome Robbins was an American-born dancer and a significant choreographer in ballet, musical theater, and film. Robbins contributed modern ballets to the repertory of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre. His artistic works are influenced by ordinary people and reflect current times.

Watch This

Short documentary that highlights scenes of Fancy Free with commentary by Daniel Ulbricht and Ella Baff. Fancy Free is set in the 1940s; this ballet is about the escapades of sailors onshore. Fancy Free is the precursor for the musical On the Town.

Robert Joffrey (1930–1988)

In 1953, Robert Joffrey began his company, Joffrey Ballet, as a small touring group traveling in a single van. It is primarily known for its pop-culture ballets, like Astarte, and historical recreations of ballets like Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, Fokine’s Petrouchka, and Massine’s Parade.

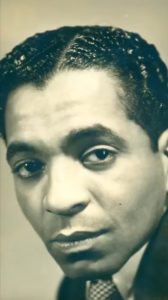

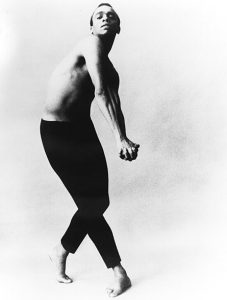

Arthur Mitchell

Arthur Mitchell was the first African-American principal dancer to perform with a leading national ballet company, New York City Ballet. In 1969, in response to news of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, Mitchell created a ballet school in his childhood neighborhood. The Dance Theatre of Harlem rose from the ballet school, a classical ballet company composed primarily of African-American dancers.

Mitchell wanted to produce ballets that would raise the voices of people of color and create opportunities for them to dance professionally. He used his company as a platform for social justice. In his Creole Giselle, Mitchell reimagined the romantic ballet and set it in Louisiana during the 1840s. According to the Dance Theatre of Harlem’s program notes, “During this time, social status among free blacks was measured by how far removed one’s family was from slavery. Giselle’s character is kept the same; her greatest joy is to dance. Albrecht is now Albert, and the Wilis are the ghosts of young girls who adore dancing and die of a broken heart.”

Watch This

This archival material from Creole Giselle includes pictures and dancing clips narrated by the dancers of the original ballet, Theara Ward, Augustus Van Heerden, and Lorraine Graves.

Check Your Understanding

Contemporary Ballet: Ballet in the 21st Century

Contemporary ballet is a dance genre that uses classical techniques (French terminology) that choreographers manipulate and blend with other dance forms, such as modern dance.

Alonzo King LINES Ballet

Alonzo King is an American choreographer who initially studied at the ABT. King also danced with notable choreographers Alvin Ailey and Arthur Mitchell before founding his company, LINES Ballet. LINES Ballet is located in California, where King uses Western and Eastern classical dance forms to create contemporary ballets.

BalletX

BalletX was founded in 2005 by Christine Cox and Matthew Neenan and is located in Philadelphia. The mission of BalletX is to expand classical vocabulary through its experimentation to push the boundaries of ballet.

Watch This

Christine Cox and Matthew Neenan discuss the mission of BalletX. The footage shows clips of the company’s performances, pictures, and interviews with the company members.

Complexions Contemporary Ballet

In 1994, Complexions was founded by Dwight Rhoden and Desmond Richardson. The mission of Complexions is to foster diverse and inclusive approaches in the making and presentation of their works to inspire change in the ballet world.

Watch This

Excerpt from WOKE that uses music from Logic to explore themes of humanity in response to the political climate.

Other Notable Contemporary Ballet Artists

- Nederlands Dans Theater, founded in 1959, is a Dutch contemporary dance company

- William Forsythe founded the Forsythe Company (2005–2015), integrating ballet with visual arts.

- Jiří Kylián blends classical ballet steps with contemporary approaches to create abstract dances.

- Amy Hall Garner combines ballet, modern, and theatrical dance genres.

- Trey McIntyre founded the Trey McIntyre Project in 2005, combining ballet and contemporary dance with visual arts.

- Ballet Hispánico, founded by Tina Ramirez in 1970, blends ballet with Latinx dance to create more opportunities for dancers of color, known as one of America’s Cultural Treasures.

- Justin Peck is the resident choreographer for New York City Ballet, creating new works, and earned a Tony Award for his choreography in the revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel.

Inclusivity

From its origins in the elite white-only courts of France and Italy and well into the present day, Western dance forms had a history of exclusionism. In the United States, the first black ballet dancer who broke the color barrier in 1955 to dance in a major ballet company was Raven Wilkinson. Wilkinson danced and toured with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Racial segregation was at its height during this time, forcing Wilkinson to deny her race when performing at most venues. After facing years of discrimination, Wilkinson eventually left the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. After facing rejection from several American ballet companies, Wilkinson was hired to dance with the Dutch National Ballet. Wilkinson later became a mentor to Misty Copeland.

In 2015, Misty Copeland became the first African-American female principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre. Copeland is also the first woman of color to take the lead role of Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. Her road to principal dancer was difficult, as many claimed she had the wrong skin color to dance professionally. Due to the racism faced throughout her life, Misty Copeland uses her platform to bring awareness to the challenges people of color face in the ballet world by advocating for diversity.

Watch This

Misty Copeland’s interview on race in ballet.

Misty Copeland

Racial barriers have caused choreographers to challenge the traditional Eurocentric forms of ballet. Hiplet, a fusion of ballet movement and hip-hop, was created by Homer Hans Bryant to provide opportunities for dancers of color to connect to ballets and express themselves in a contemporary and culturally relevant way.

Watch This

In this video, Hiplet creator Homer Hans Bryant discusses how he developed this dance style.

Gender Roles

Ballets historically tend to follow stereotyped gender roles that emphasize femininity and masculinity. These conventional standards are reinforced in the movements, roles, costuming, and partnering displayed in ballets. In pas de deuxs in classical ballets, female dancers are paired with male dancers. Female dancers are often portrayed as delicate, complacent, ethereal beings. In contrast, male dancers are presented as dominant and strong; they lift their female partners, enforcing the image of men supporting women.

Mathew Bourne

In 1995, Matthew Bourne took a contemporary approach to classical ballet in his reimagined Swan Lake. Bourne disrupts societal expectations by replacing the female swans with men. In the male-male pas de deux, the dancers lift and support each other, shifting the power dynamics to emphasize equality in the movement.

Watch This

“The New Adventures” excerpt of Swan Lake.

LGBTQIA+ Representation

Ballets have also reinforced heterosexual norms and narratives. Societal ideals of feminine and masculine stereotyped gender roles have caused inequality in the representation of the LGBTQIA+ community. Although there are openly gay male dancers in ballet, their roles pressure them to adhere to rigid ideas of masculinity. The chivalrous prince rescues the helpless female character. Historically, the Romantic era brought the ballerina to the forefront, and ballet became perceived as a feminine art form. Dancers who identify as lesbians are excluded from the ballet narrative because movement qualities reinforce binary norms.

The representation gap for all sexual orientations has excluded people in the LGBTQIA+ community. Many feel the pressure to conform to rigid gender stereotypes. LGBTQIA+ artists today are using their platforms to address the lack of representation and challenge ballet traditions to include a wide spectrum of sexuality.

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo adds a twist of humor in classical ballets. The company, founded in 1974, features men performing en travesti (in the clothing of the opposite sex). The dancers in this company challenge the gender norms of ballet by assigning men to traditionally female roles.

Watch This

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo’s version of Swan Lake. In the pas de quatre, or dance of four, the dancers perform a parody of the “Dance of the Little Swans.”

Ballez

Ballez is a ballet company founded by Katy Pyle in 2011. Ballez aims to dismantle the patriarchal structure of ballet to create inclusive spaces for the representation of queer dancers. In 2021, Pyle reimagined the romantic ballet Giselle. In Ballez’s production Giselle of Loneliness, Ballez highlights the experiences of queer and gender non-conforming, non-binary, and trans dancers. The dancers perform an audition solo inspired by the “mad scene” from the original Giselle that comments on the personal challenges and experiences affecting their relationship with ballet from an LGBTQIA+ lens.

Watch This

An interview with Katy Pyle.

Body Types

Generally, ballet centers on European aesthetics, including the ideal body shape. George Balanchine, the founder of New York City Ballet, favored a ballet dancer with a long neck, sloped shoulders, a small rib cage, a narrow waist, and long legs and feet. These ideals have resulted in the pressure to maintain a slender physique and have caused body dysmorphia in many dancers. Copeland has stated that at the age of 21, artistic staff commented on how her body “changed” and their hopes to see her body “lengthen.” According to Copeland, “That, of course, was a polite, safe way of saying, ‘You need to lose weight.’” In 2017, Misty Copeland released her health and fitness book Ballerina Body: Dancing and Eating Your Way to a Leaner, Stronger, and More Graceful You. Copeland shares her health-conscious approaches to developing healthier and stronger bodies in this book.

Ballet Timeline

Summary

Ballet is a Western classical dance form with a rich history—beginning in the Renaissance as a royal court entertainment infused with social and political purposes, eventually developing into a codified technique. Over time, ballet transformed, experiencing costume changes in the Enlightenment that led to dancers being able to express themselves without being confined to restrictive clothing. In the Romantic era, ballet d’action emerged, emphasizing emotions over logic to help communicate the ballet’s story. There were also technical elements such as flying machines that gave the impression of dancers floating onstage. The unique theater effects led to female dancers beginning to dance en pointe. During the Classical period, Russia became the leader of ballet, with government support to establish ballet schools. Ballet shifted in pursuit of virtuosity, demanding greater technique from dancers. The Ballet Russes made a significant impact by modernizing ballets, bringing ballet to other world regions, and helping establish ballet in America, and a new ballet style was formed, neoclassical. Today, choreographers challenge the ballet traditions and embrace various dance genres to blend with ballet, known as contemporary dance.

Check Your Understanding

1. Ballet Pantomime

Choreograph a short pantomime that tells a story through dialogue. You may either choose to ask a friend or family member to exchange dialogue or perform your dance alone. Use a combination of traditional pantomime gestures from the selected videos and add original gestures and facial expressions. Record your pantomime and share the link on the discussion board (minimum of 20 seconds). Include a script summarizing what your pantomime says.

Here are some topic examples you might consider:

- Activities or sports you like to participate in and why.

- What makes you happy (taking walks, spending time with friends, etc.).

- Aspects about your day.

- A place you’ve traveled to and what you saw.

- Words of encouragement/affirmation.

2. Elements of Dance in Ballet

DIRECTIONS: Utilizing the Elements of Dance, watch two videos from different ballet eras (Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Romantic period, Classical, Avant-Garde, Neoclassical, and Contemporary) and write a reflection speaking to the salient qualities observed. Answer the following prompts:

- Compare and contrast the aesthetics observed using the Elements of Dance.

- How does the movement reflect the ballet era? How does the period reflect the movement?

3. Dear Catherine de’ Medici

DIRECTIONS: Write a letter to Catherine de’ Medici that speaks to the current discourse in the ballet world. Select one of the discussion topics found in this book and watch the associated video (race in ballet, gender roles, LGBTQIA+ representation, or body types) to reflect, respond, and advocate how the ballet world can address these issues. Please reference the class book or use the internet to conduct further research. Post your assignment on the discussion board and cite references (minimum of 150 words).

References

“History of Ballet.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, June 24, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_ballet.

Kassing, Gayle. Discovering Dance. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2014.

“Ballez.” BALLEZ, www.ballez.org/.

Bried, Erin. “Stretching Beauty: Ballerina Misty Copeland on Her Body Struggles.” SELF. SELF, March 18, 2014. https://www.self.com/story/ballerina-misty-copeland-body-struggles.

Harlow, Poppy, and Dalila-Johari Paul. “Misty Copeland Says the Ballet World Still Has a Race Problem and She Wants to Help Fix That.” CNN. Cable News Network, May 21, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/21/us/misty-copeland-ballet-race-boss-files/index.html.

Lihs, Harriet R. Appreciating Dance a Guide to the World’s Liveliest Art. Princeton Book Company, 2018.

Loring, Dawn Davis, and Julie L. Pentz. Dance Appreciation. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2022.

“Ballet.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, July 20, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballet.

Ambrosio, Nora. Learning about Dance: Dance as an Art Form & Entertainment. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, 2018.

Learning Objectives

- Explain the similarities and differences between ballet and modern dance.

- Identify key techniques and prominent figures in modern dance history.

- Understand the history of Western performance dance and summarize major events in the course of its development.

“Dance is the hidden language of the soul.” —Martha Graham

What Is Modern Dance?

In the early 20th century, choreographers broke away from the strict traditions of ballet to develop dance as varied and rich as the American melting pot. Choreographers drew upon the styles of many cultures to create a new dance form as diverse as the citizens and expressive of the independence of the American spirit. Black dancers and choreographers explored their African and Caribbean roots and shaped their own form of expressive modern dance. Others sought new movement to depict the human condition. Inevitably, dances were shared, merged, and reimagined. No matter the case, early pioneers of modern dance explored new ways to express themselves in more natural and free form while conveying the spirit of their times.

Modern Dance Characteristics

Modern dance technique is unlike ballet’s codified set of movements used worldwide. Modern dance styles are individualized and, for the most part, named after the person who developed them; for instance, José Limón created the Limón Technique. Although modern dance techniques vary, movement concepts are embedded throughout techniques, sharing overarching principles. Let’s take a look at the movement concepts in modern dance.

Dynamic Alignment and Flexibility

All dancers use dynamic alignment. However, in Modern dance, emphasis is given to the core along with the pelvis, which is the center from which all movement originates. The core keeps the dancer grounded and stable. Modern dancers also use freer or unrestrained movement of the torso that allows for flexibility in all directions.

Watch This

Graham Technique with dancers demonstrating contractions. The torso is in a concave shape created by the core contracting (abdominals); as a result, the pelvis “tucks under” and the chest reacts by rounding forward.

Gravity

In modern dance, gravity is accepted, which acts as a partnership with the body utilizing the dancer’s weight paired with momentum.

Watch This

An example of the Limón Technique called fall and recovery that uses the body’s weight with momentum to surrender into gravity. The dancer is demonstrating arm swings, known as release swings. In this action, the dancer begins with the body in a vertical position and the arms swing in any direction. The dancer allows the momentum from the swing to propel the body in the direction of the arm, giving in to gravity.

The Tanz Theater Münster company dancers interact with the floor. They can quickly move between floor work and standing movement.

Breath

The use of breath is a prominent component of modern dance. Dancers do not always attempt to hide their breathing. The inhalation and expiration of breath provide a natural physical rhythm that assists in executing movement.

Bare Feet, Flexed Feet, and Parallel Feet

Modern dance is often performed barefoot. Many exercises utilize the feet in a parallel position. Unlike traditional ballet, modern dance can use a flexed foot instead of a pointed foot.

Improvisation

Improvisation is the practice of unplanned movement. Many choreographers use improvisation as the basis for generating movement ideas for choreography. Through active investigation, choreographers select and further develop the movements explored from their improvisation to consider how they can be applied in their dance concept.

Watch This

The dancer improvises movement that includes floor work and standing movement.

The Pioneers: First and Second Generations

Historical Context

Modern dance appeared in Germany and the United States in the early 20th century. In the late 19th century, the second Industrial Revolution brought significant changes. The rise of people who lived and worked in cities, mainly middle-class or white-collar workers, meant they lived less active lifestyles, resulting in the task of public health officials to prevent the spread of diseases caused by sedentary lifestyles. Emphasis on the benefits of maintaining a regular exercise regimen, such as dance, gymnastics, and sports, were highly praised. European theorists Delsarte and Dalcroze introduced methods for understanding human movement that were presented to colleges as “aesthetic dance.” These theorists made an impression on emerging modern dancers as they provided new ways to uncover the expressive qualities of the body by responding to internal sensations with greater freedom in movement possibilities.

Loie Fuller (1862–1928)

Loie Fuller was a former actress and skirt dancer, a popular dance form in Europe and America mainly found in burlesque and vaudeville. Fuller is known for her dramatic manipulation of fabrics and lighting designs, creating visual effects such as butterfly wings and fire images. She made these effects by shining light onto her voluminous silk costumes. Fuller also experimented with electrical lighting, colored gels, and projections.

Watch This

Fuller’s debut as a dancer in Serpentine Dance.

Isadora Duncan (1877–1927)

Isadora Duncan rejected her early training in ballet technique, feeling the movement and costumes were restrictive and lacked personal expression. Instead, she explored more natural movements, such as walking, running, skipping, and jumping. Instead of ballet attire, she emulated the Greeks when she wore tunics, danced barefoot, and performed dances about nature. It gave her movement a sense of freedom and abandonment.

Historically, modern dance has been tied to cultural forces that reflect society. Duncan’s dances expressed the human condition, especially women’s rights. She traveled throughout America and eventually settled in Europe, where she founded her school. Duncan trained dancers and called them “Isadorables.”

Watch This

Duncan performs outdoors.

“Denishawn”

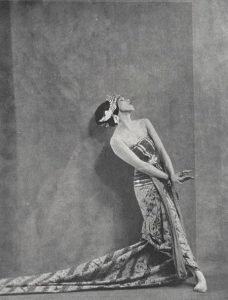

Ruth St. Denis (1879–1968)

Ruth St. Denis became fascinated with cultures worldwide when she saw an advertisement for Egyptian Deities cigarettes. The image of the goddess on the cigarettes inspired her dances honoring goddesses and deities based on her impressions of Indian, Egyptian, Spanish, and Javanese dance forms that weren’t culturally accurate. Instead, they were a reflection of her aesthetics.

Watch This

Denis’s East Indian Nautch Dance inspired by the dance practiced by the nautch girls of India.

Ruth St. Denis married Ted Shawn; this also began a creative partnership. Together they founded the Denishawn School, creating a diverse curriculum that included ballet, Asian dances, and dance history. They encouraged dancers to connect their dancing body to their mind and spirit. Through their school emerged the first generation of modern dancers.

Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn parted ways. St. Denis turned her attention to religion and continued teaching South Asian dance forms. Ted Shawn went on to found Jacob’s Pillow in Massachusetts, the nation’s oldest dance festival.

Ted Shawn (1891–1972)

Ted Shawn formed an all-male dance company called Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers, hoping to make modern dance a respected profession for male dancers.

Watch This

Kinetic Molpai is a dance work in 12 parts; it features Ted’s all-male company, who form a chorus. A solitary man, the leader, joins them sporadically. Fun fact: Shawn recruited athletes from Springfield College that had no experience in dance and trained them.

First Generation: Discovering Personal Voices

Dancers from the Denishawn school began to branch out as they grew restless with the company’s artistic vision, which focused on exotic themes that proved to be moreso entertainment on the vaudeville circuit. Instead, the first-generation dancers wanted to express their creative voice and push the art form’s boundaries, resulting in various codified modern techniques.

Martha Graham (1894–1991)

Martha Graham studied dance at Denishawn but left to form her own company and develop her own technique. She believed that dance should show the struggle and pain that comes with life. She developed “contract and release,” a technique that shows movement initiating from the center of the body meant to embody conflict. This technique involves percussively tightening the body’s core muscles (centered on the lower abdominals and pelvis), followed by a release of tension (the spine lengthens to return to an elongated neutral posture). This technique utilizes breath to support the movement; the dancer begins with an inhale, then an exhale, allowing the body to contract, and lastly is followed by an inhale to release and return the body to vertical/neutral alignment.

Graham’s repertoire included dances based on Americana, such as Frontier and Appalachian Spring. She also created dances based on Greek myths, as in Night Journey, and emotional dances.

Watch This

Lamentation is a signature solo performed by Graham. Graham embodies grief as she contorts her body within the stretchy fabric.

Humphrey-Weidman

Doris Humphrey (1895–1958) and Charles Weidman (1901–1975)

Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman were former Denishawn students who had a creative partnership and together founded the Humphrey-Weidman company. In collaboration with Weidman, Humphrey created a movement technique based on the body’s reaction to gravity and weight called “fall and recovery.” Humphrey believed the body constantly moves in between the “arc between two deaths,” in which the body moves in a successive pattern responding to gravity.

Watch This

Weidman discusses the concept behind “fall and recovery.”

Lester Horton (1906–1953)

Lester Horton became interested in dance when he saw Native Americans doing indigenous dances. He is most renowned for his technique called the “Horton Technique.” This technique embeds strength-building and flexibility principles in fortification exercises (set exercises designed to increase technical skills underpinned with anatomy principles).

Horton also had a company that is credited with founding the first racially integrated dance company in America. His choreography drew inspiration from Native American and African dance forms.

Watch This

Students perform the Horton Technique, working on a flat back series that aims to strengthen and stretch the legs, core, and back.

(Osborne) Hemsley Winfield (1907–1934)

(Osborne) Hemsley Winfield was an African-American modern dancer who sought ways to create equitable opportunities for Black dancers. Winfield was inspired by the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that brought African-American artists to the forefront as changemakers. In 1931, he co-founded the Bronze Ballet Plastique with the help of Edna Guy, later to be renamed the New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group, which was the first African-American modern dance company in the United States. Winfield also established a dance school to provide dance instruction. After Winfield passed away, the New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group dissolved due to a lack of financial support.

Edna Guy (1907–1983)

In 1924, Edna Guy was the first African-American to study with Denishawn. However, due to the prevalent racial segregation, she was only able to perform for in-house recitals. She later co-founded the New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group alongside Hemsley Winfield. In 1937, Guy and Allison Burroughs staged Negro Dance Evening, highlighting African diaspora dances.

Second Generation: Expanding the Horizons of Modern Dance

The second-generation modern dancers either continued following their predecessors’ work or went in a different direction by creating new dance techniques, styles, and unorthodox choreographic approaches.

José Limón (1908–1972)

José Limón, originally from Mexico, danced with Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman. Eventually, Limón would form his own company and ask his mentor, Humphrey, to be the artistic director. Limón expanded on Humphrey’s “fall and recover” technique and emphasized fluid, sequential movement and the use of breath as the origin and facilitator for movement as a way to approach organic movement. Limón’s legacy is still alive today. His company continues to perform, dancing the repertory of Limón along with new works from artists.

Watch This

There Is a Time, based on the historic poem from the Bible, “Ecclesiastes.” This dance contains universal themes describing the human experience.

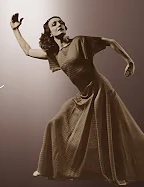

Katherine Dunham (1909–2006)

Katherine Dunham was a dancer and trained anthropologist who studied the dances of Haiti and other Caribbean islands. She performed and choreographed for Broadway musicals, movies, and concerts with the company. Dunham developed her technique that drew on principles of the African dance movement, called the “Dunham Technique.” Dunham sought to create dances that represented her African American heritage. Her work extended outside of modern dance, where she choreographed for Hollywood films. She founded a school of dance in New York City in the mid 1940s.

Watch This

Katherine Dunham’s Carnival of Rhythm, 1941.

Students participate in the Dunham Technique. The Dunham Technique utilizes classical lines and free movement of the torso that utilizes isolations and undulations paired with a dynamic range of tempos and rhythmical styles.

L’Ag’Ya. This was Dunham’s signature piece, a story-based folk ballet set in Martinique that combines many dance styles.

Pearl Primus (1919–1994)

Pearl Primus was a trained anthropologist. She secured funding to study dance abroad in Africa and the Caribbean. Primus became a strong voice of African American dance by addressing racism in the United States. One of her most noted works is “Strange Fruit,” based on the poem by Lewis Allan about the lynching of Black people. In 1979, she and her husband established the Pearl Primus Dance Language Institute, which centered classes in various African dance styles. Primus also founded her company Earth Theatre, which toured nationally.

Watch This

Pearl Primus performing solo tabanka teach.

Talley Beatty (1918–1995)

Talley Beatty is a Louisiana native born in Shreveport. He was initially a dancer and student of Katherine Dunham and appeared in Broadway shows and films. In 1952, he established his company that toured in the United States and Europe with a program called “Tropicana,” featuring African and Latin American dance styles. Beatty’s choreography centered on themes of African-American life. Renowned dance companies, like the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Dance Theatre of Harlem, have restaged his works.

Watch This

In this video, former ADF scholarship student and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater member Hope Boykin and choreographer and dancer Duane Cyrus speak about their pivotal experiences working with Mr. Beatty on his classic piece Road of the Phoebe Snow (1959).

Donald McKayle (1930–2018)

Donald McKayle was one of the pioneering African-American modern dancers to focus on socially conscious works speaking to the experience of Black people in the United States. During the span of his career, McKayle choreographed several masterworks, including “Rainbow Round My Shoulder,” exposing the harsh working conditions of imprisoned Black men set to chain-gang songs. For his tireless contributions, he holds honorable mentions as “one of America’s irreplaceable dance treasures” from the Dance Heritage Coalition.

Watch This

This dance is a staging from the Labanotation score.

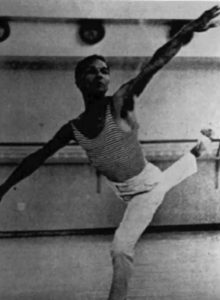

Alvin Ailey (1931–1989)

Alvin Ailey is another important second-generation dance artist. He studied with Lester Horton, Katherine Dunham, and Martha Graham. His independent career began after the death of his mentor, Lester Horton. In 1958, he formed the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, based in New York. Ailey became an influential voice that brought awareness to the inequalities faced by African-Americans. Ailey was dedicated to highlighting and preserving the African-American experience by drawing inspiration from his heritage, including spirituals, blues, and jazz.

Watch This

“Sinner Man,” an excerpt from Revelations. Ailey used Lester Horton’s technique in many of his dances.

Ailey sought out other African-American choreographers to set dances for his company. In the video below, you will see Wayne McGregor’s Chroma, Ronald K. Brown’s Grace, and Robert Battle’s Takademe. It also has Alvin Ailey’s masterpiece Revelations. If you have not seen Revelations before, please watch that at the least.

Watch This

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre video online.

https://www.alvinailey.org/performances-tickets/ailey-all-access

Ailey choreographed myriad works. His work Revelations is an American classic. He received many honors in his career for his work in the arts and in civil rights, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Watch This

By turns muscular and lyrical, The River is a sweeping full-company work that suggests tumbling rapids and meandering streams on a journey to the sea.

Erick Hawkins (1909–1994)

Erick Hawkins initially studied at the School of American Ballet, eventually meeting Martha Graham. Hawkins was the first man invited to perform with Graham’s company. Hawkins created a dance technique that integrated kinesiology principles coupled with what would be later known as somatic studies that connect the body, mind, and soul. He was interested in the body’s natural movements and was inspired by Zen principles, Native Americans, and the beliefs of Isadora Duncan.

Watch This

Plains Daybreak, inspired by Native American dances and stories.

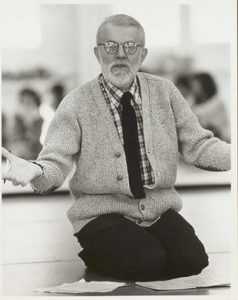

Paul Taylor (1930–2018)

Paul Taylor danced with Graham’s company for several years. In 1959, he formed the Paul Taylor Dance Company. His choreographic works in modern dance ranged from abstract to satire themes. Eventually, Paul Taylor found his niche in classical modern training with remnants of ballet or a lyrical dance style underpinning the movement. His piece Esplanade has choreography couched in pedestrian movements (plain, everyday movements like walking, skipping, running). You may remember seeing a sample of this in Chapter 18: Elements of Dance.

Watch This

Taylor’s Airs.

Merce Cunningham (1919–2009)

Merce Cunningham initially danced with Martha Graham; however, he left to follow his own artistic vision. He formed a creative collaboration with his life partner, John Cage. They experimented with avant-garde ideas that emphasized that dance could be independent of music and narrative or as a separate entity. Cunningham developed “chance dance,” in which fragments of choreography were randomly shuffled to create new and spontaneous dances determined by chance acts of rolling dice or flipping a coin. Cunningham also used computer software to aid in generating movement.

Watch This

The contributions Cunningham made to modern dance.

Merce Cunningham’s Work Process

Alwin Nikolais (1910–1993)

Alwin Nikolais explored the geometries of form and dance. He created painted glass slides to light his dances like in this video of Crucible. He created his own costumes and props and most of the music for his dances, thereby controlling the whole stage environment.

Watch This

Excerpt from Crucible.

Third Generation: The Postmodern Movement

The Postmodern movement emerged during the early 1960s and reflected the revolutionary mood of the times. Postmodern choreographers began to question the reasons for dance-making, who could dance (Can untrained people be performers?), what could be used as music (Can silence be music?), and experimented with where dance could occur. Performances began featuring ordinary movements with non-dancers and were done in non-traditional settings such as art galleries, churches, outdoor settings, and even on the sides of buildings. Another feature that emerged in the postmodern period was the rise of dance collectives with no one named choreographer. Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union are great examples of this trend.

Robert Dunn (1928–1996)

Robert Dunn was a musician that played piano for Merce Cunningham’s classes. Dunn was drawn to the radical principles of John Cage and attended his classes on composition. Eventually, he would use the concepts learned from Cage and apply them to dance in choreography workshops attended by Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and Tricia Brown, among others. Dunn encouraged them to be risk-takers by encouraging ongoing experimentation.

Judson Dance Theater

Dunn’s dance composition classes found residency at Judson Memorial Church and adopted the name of Judson Dance Theater for their dance collective. The Judson Dance Theater dancers met weekly and were given assignments, performed their choreographic works, and critiqued each other. The artists mainly used improvisation as the source for generating movement. The Judson Dance Theater eventually disbanded, and the Grand Union emerged, created by several of the Judson Dance Theater dancers and new members.

Grand Union

The Grand Union was a collaborative effort with all dancers contributing to the artistic process of the group. They experimented with multimedia performance art and improvisation. Their creative research encouraged artists to expand their definitions of dance to include pedestrian movement (e.g., walking and running) and task-oriented movement (e.g., dancers must maintain physical contact throughout the entire dance). These allowed for the participation of both trained and untrained dancers. In addition, the artists sought out alternative spaces for dancing, such as warehouses and lofts. Choreographers made statements with their works rather than storytelling.

Yvonne Rainer (1934– )

Yvonne Rainer studied with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Robert Dunn’s choreography workshop influenced her work as a choreographer. She was interested in the use of repetition, games, tasks, and partnering, which would become common choreographic practices employed in dance-making.

Watch This

Rainer’s Trio A, a solo dance featuring pedestrian movement.

Steve Paxton (1939– )

Steve Paxton studied and performed with Limón and Cunningham. He was inspired by the improvisation techniques explored during the Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union collaborations. Paxton developed “contact improvisation,” which has principles based on weight-sharing, touch, and movement awareness paired with pedestrian movement.

Watch This

An example of contact improvisation. The dancers maintain a point of contact and trade off weight sharing.

Trisha Brown (1936–2017)

Trisha Brown studied with several notable teachers, including Merce Cunningham. In the early 1970s, she founded the Trisha Brown Company, engaging in “site-specific” works. These are performance spaces outside the conventional theater, such as dances on rooftops. She also explored avant-garde and postmodernist ideas to experiment with pure movement and repetitive gestures in dance.

Watch This

Brown’s Man Walking Down the Side of a Building.

Fourth Generation: Contemporary Modern Dance

During the mid 1970s, there was a shift back to more technical-based movements with a return to the proscenium stage. We are using the term Contemporary Modern to refer to this current genre.

Remember that the term Modern refers to those early choreographers who broke away from old-world ballet and developed an original abstract modern point of view. After a while these early modern choreographers codified their technique styles. At this time, modern refers to any of the choreographers who studied with or were influenced by the first- or second-generation modern dancers and are now codifying their own technique. Postmodern dance broke away from modern technique and used pedestrian movement (everyday gestures or actions such as walking, sitting, or opening a door).

Contemporary Dance is an expansive term meaning current, what’s happening now. It is a broader, more individualistic, expressive style of dance.

Contextual Connections

Dance Magazine’s Victoria Looseleaf helps to define the difference between Contemporary and Modern Dance

https://www.dancemagazine.com/modern_vs_contemporary/

“Perhaps modern and contemporary genres have taken on new meanings because the global village has created a melting pot of moves, a stew of blurred forms that not only break down conventions and challenge definitions, but, in the process, create something wholly new, but as yet unnamed.”

Looseleaf went on to speak with several dance professionals about their thoughts on the topic.

Contextual Connections

Mia Michaels, Choreographer for So You Think You Can Dance and various pop stars and dance companies, Los Angeles

“I’m a little responsible for So You Think You Can Dance co-opting the term ‘contemporary.’ When we first started the show, Nigel [Lythgoe] was calling it lyrical. I said, ‘It’s not lyrical, it’s contemporary.’ We’ve created a monster. Contemporary is an easy way out—it’s when you don’t know what to call it, you call it contemporary. I feel like dance is fusing all the forms and that the uniqueness of each genre is starting to be muddled. It feels regurgitated and I want it to change desperately. I’m wanting to see where these new legends and voices—like Fosse, Robbins, Graham—are going to pop up.”

Jennifer Archibald, Founder/Director, Arch Dance, New York City

“Contemporary is a collection of methods that have been developed from modern and postmodern dance. It’s also a cycle of shedding techniques we’ve learned in favor of personal expression of movement. Where modern dance moved against the grain of ballet, contemporary moves against the grain of classical modern techniques.

“Contemporary is not a technique, it’s a genre associated with a philosophy and exploration of different natural energies and emotions. There’s a physicality that’s appealing today, but there’s a spirituality of the contemporary movement that has been lost with the new generation in this free-for-all of different methods.”

Twyla Tharp

Twyla Tharp trained with the American Ballet Theatre, modern dance artists Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, and Luigi and Matt Mattox jazz dance educators. Tharp began choreographing dances that blend dance genres, such as modern dance, jazz, tap, and ballet. Tharp has choreographed “more than one hundred sixty works: one hundred twenty-nine dances, twelve television specials, six Hollywood movies, four full-length ballets, four Broadway shows and two figure skating routines. She received one Tony Award, two Emmy Awards, nineteen honorary doctorates, the Vietnam Veterans of America President’s Award, the 2004 National Medal of the Arts, the 2008 Jerome Robbins Prize, and a 2008 Kennedy Center Honor.” Bio | twyla tharp. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.twylatharp.org/bio

Watch This

Tharp’s Deuce Coupe, danced to music by the Beach Boys and considered the first crossover between ballet and modern dance.

Twyla Tharp’s Famous “Eight Jelly Roll” Dance from Twyla Moves, American Masters, PBS.

Garth Fagan

Garth Fagan developed the “Fagan Technique,” blending modern dance, Afro-Caribbean dance, and ballet. He received his training from Limón, Ailey, and Graham. Fagan has created works for notable companies like Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and New York City Ballet.

Watch This

Fagan’s From Before, performed by the Alvin Ailey Dance Company.

Contextual Connections

Disney’s The Lion King

Fagan is perhaps best known for his legendary work on Disney’s Broadway musical The Lion King (1997) in which he brought the animals to life by combining clever costume pieces with dance evocative of the animals in the story. In this video you will get a glimpse of the man and his choreography.

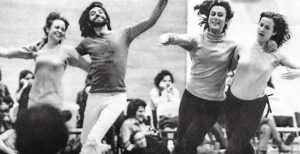

Pilobolus

Pilobolus is a dance collective created in the late 1970s by Dartmouth college-student athletes Robby Barnett, Martha Clarke, Lee Harris, Moses Pendleton, Michael Tracey, and Jonathan Wolken with the guidance of their teacher Alison Chase. Pilobolus branched from a choreography class experimenting with gymnastics and improvisation to create images by sculpting bodies.

Watch This

Pilobolus performs Shadowland.

Mark Morris

In the early years of his career, Mark Morris performed with the companies of Lar Lubovitch, Hannah Kahn, Laura Dean, Eliot Feld, and the Koleda Balkan Dance Ensemble. The Mark Morris Dance Group was formed in 1980 when he was just 24. Since then, Morris has created over 150 works for the company. In 1990, he founded the White Oak Dance Project with Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Watch This

Reporter Jeffrey Brown talks to the famed choreographer on his production of “L’Allegro” on PBS’s Great Performances.

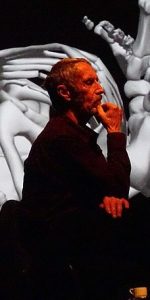

Bill T. Jones

Bill T. Jones is known for blending controversial subjects into his modern dance choreography. Bill T. Jones and his life partner, Arnie Zane, founded the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company in the early 1980s. Their creative works explored LGBTQIA+ themes of identity and racial tensions. Following the death of Zane, who succumbed to AIDS, Jones continued their work with the company. Bill T. Jones uses his platform as socio-political activism using dance, autobiographical elements with narrative, and theatrical components.

Watch This

An excerpt from D-Man in the Waters performed by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. D-Man in the Waters is a political response to the AIDS epidemic honoring those who have succumbed to the disease.

His piece What Problem? in which Bill T. Jones explores current events and questions racism, equality, brutality, and change.

Jawole Willa Jo Zollar

In the early 1980s, Jawole Willa Jo Zollar founded Urban Bush Women. Her training began with the Dunham technique and studying various African diaspora dance forms. Urban Bush Women started as an all-women group and predominantly centered their work from women’s perspectives; however, the company has included male dancers. The mission of Urban Bush Women is to raise the voices of people of color to advocate for social change addressing issues of race and gender inequalities. Jawole Willa Jo Zollar blends personal testimonies from the company members to create narratives (text) combined with African and contemporary dance forms.

Watch This

“Hair and Other Stories,” exploring body image, gender identity, and race through conversations about hair care.

Lorenzo “Rennie” Harris

Lorezno “Rennie” Harris brings Hip-Hop to the concert stage, often telling stories of the human condition. In 1992, Harris founded his company, Puremovement, located in Philadelphia, in an effort to preserve hip-hop culture. Harris has choreographed contemporary dance works for modern companies like the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. His works will be further in this book.

Watch This

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre performs an excerpt from Harris’s Exodus.

Robert Battle

Robert Battle is the current Artistic Director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. He was a choreographer for the Ailey company. A graduate of Juilliard, he joined the Parsons Dance Company and founded his own company, Battleworks Dance. Battle has received numerous prestigious awards, such as being honored in 2005 by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts as one of the “Masters of African-American Choreography.”

Watch This

Takademe, choreographed in 1999.

Sean Dorsey

Sean Dorsey is a transgender and queer choreographer. Dorsey founded the Sean Dorsey Dance Company based in San Francisco, centering his work on LGBTQIA+ themes. In 2002, Dorsey established Fresh Meat Production, a non-profit organization that advocates for equity in gender-nonconforming communities through commissions of new dances and community engagement programs.

Watch This

An excerpt of Boys in Trouble, a social commentary on the rigid ideas of gender and masculinity.

AXIS Dance

In the late 1980s, AXIS Dance was co-founded by Thais Mazur, Bonnie Lewkowicz, and Judith Smith. AXIS dance is one of the first dance companies to create inclusive spaces for dancers of all physical abilities. Through collaborative efforts, the company developed dance known as physically integrated dance, which aims to broaden the idea of dance and who a dancer is through movement that respects a “wide spectrum of physical attributes and disabilities” (Axis dance company, 2022. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=AXIS_Dance_Company&oldid=1074988620).

Watch This

AXIS Dance’s rehearsal process, featuring commentary by Artistic Director Marc Brew.

Camille A. Brown