5 Chapter 5: Renaissance to Realism

The Renaissance

Renaissance literally means “rebirth.” About the early 1400s, there was a revival of interest in the art, architecture, literature, and culture of the classical world. This period lasted for about three hundred years and is called the Renaissance period. Major technical innovations in painting, such as the introduction of oil painting, foreshortening, and single-point perspective, date from this period. The interest in the anatomically correct rendering of the human body made the illusionistic rendering of the human world possible. At the peak of the Renaissance, between roughly 1500 and 1530, one finds three great artists who define this spirit: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Most of our knowledge on the Renaissance artists comes from Giorgio VASARI (1511–1574), Italian painter, writer, historian, and architect, more famous for his biographies of Italian Artists. In northern lands, especially in Flanders, Jan van Eyck will lead us to explore the beginnings of middle-class life in cities and the discovery of the self in self-portraits. By about 1520, the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church was challenged by Martin Luther and the rise of the Reformation. A long series of wars and a split between the Protestant, text-centered approach to Christianity, rejecting art and decoration, and the Catholic, Baroque tradition of the Counter-Reformation, focusing on faith, mysticism, theatricality, storytelling, and decoration, was a consequence. We will take a look at secular art from the Protestant Netherlands of the 17th century, which prioritized portable art. We will study the kinds of imagery typical for this new type of art, such as group portraits, domestic scenes, landscapes, low life scenes, and still lives. The Medici family of bankers are known as the “godfathers” of the Renaissance, sponsoring many artists. They produced 4 popes, 2 Queens of France, and acquired the title Duke of Florence.

Masaccio: The Master of Florentine Painting

Another artist working in Florence at this time was Masaccio, a master of Florentine fresco painting, who continued the earlier steps toward naturalism made by Giotto. Masaccio will fully master two more major innovations of the Italian Renaissance: single-point perspective and chiaroscuro (depiction of light and shadow).

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity shows another critical development in Renaissance art: the use of accurate single-point perspective. An intuitive understanding of perspective existed in Roman wall painting, but a complete understanding was only obtained during the early Renaissance.

Masaccio, Holy Trinity, Santa Maria Novella, Florence, ca. 1428, fresco

- 3 levels—tomb, earth, heaven

- This is the first painted space that can actually be measured using the laws of perspective

- Memento Mori by skeleton: “I was once what you are, and what I am you too will be”

- Was saved and hidden by Vasari when he renovated the church

Perspective (three-dimensionality) is achieved through illusionistic architecture, such as the vault in which the figures of the Holy Trinity are contained. The architectural frame, featuring Ionic and Corinthian columns, also shows the influence of Greek and Roman architecture. The iconography of the painting features God the Father, the Son (Christ), and the Holy Spirit; the latter is represented by a dove in the top portion; below the crucifix, we see the Virgin Mary and St. John, and on the outer portion of the architectural niche of the crucifix, we see the kneeling donors, who had paid for the decoration. The bottom portion of the fresco shows an illusionistic tomb with a skeleton, which functions as a memento mori, or “reminder of death,” to the spectator.

Watch the following video on Masaccio’s Holy Trinity. As you are watching, take note of the pictorial innovations he employed (e.g., one-point perspective) as well as the inspirations he took from classical antiquity: https://youtu.be/mdd7LhVx00o

Donatello: Revival of the Classical Nude

Another sculpture for the niches of the Or San Michele was created by Donatello. Financed by the guild of linen drapers, his statue of St. Mark was the first completely free-standing sculpture on a building since classical antiquity. The figure also bends its knee in a contrapposto pose (human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot), which many Greek and Roman statues feature. The flexed knee gives it a more life-like appearance. An example from the classical world would be the Spear Bearer, but with distinctive personalities. However, Donatello’s most famous work was yet to be commissioned by the Medici family.

Donatello, Saint Mark, Or San Michele, Florence, 1411–1413, marble

Donatello’s David represented an even more important landmark in Renaissance art because it was the first free-standing classical nude figure since antiquity. During the Middle Ages, the classical nude could not be represented because of connotations with the pagan (pre-Christian) tradition and the association of the nude body with sinfulness. However, Donatello revived the nude as a subject, reinvigorating the classical canon of proportions and the classical convention of the contrapposto pose. The choice to depict David, the biblical slayer of Goliath, was intentional, as the David story was symbolic for the independence of the republic of Florence, which had resisted and repelled many incursions from stronger, more powerful city states. Donatello’s David, although depicted as an androgynous youth, is seen triumphantly, with his foot on the head of Goliath. His glance is downcast to indicate humility. Donatello’s David was a commissioned work by the Medici. It was destined to adorn the inner courtyard of their family’s palazzo, not a public space, because it is a nude and also the feather on Goliath’s helmet caresses David’s leg, the tip ending just under David’s genitalia, making this a sensual piece of art.

Donatello, David, late 1420s–late 1450s, bronze Commission for the Palazzo Medici courtyard

- Medici commission

- Androgynies—male/female youth; if in public, would have been scandalous

- Revolutionary free-standing nude since antiquity

- Stands over Goliath’s head and holds stone from sling

- Wears shepherd’s hat with laurel wreath meaning Victory

Leonardo as a Draftsman

Leonardo returned to the subject of the Virgin on the Rocks when he completed a large, related sketch in charcoal between 1505 and 1507. This sketch showed even more relaxed conventions than seen in the painting. The iconography of the Christ child playing with infant St. John, the Virgin, and St. Ann is obviously similar to that of the Virgin on the Rocks, but the emotional ties seem to run even stronger. As in the painting, Leonardo introduced atmospheric perspective. Leonardo (1452–1519, died at 79) was left handed and did mirror writing. He was an inventor (among his inventions are the machine gun, submarine, tank, parachute, hydraulics).

Leonardo da Vinci, Sketch for Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Infant St. John, ca. 1505–1507, charcoal on paper

Leonardo wrote a lot, traveled a lot, and made many sketches, but only very few oil paintings. We can think of him primarily as a very gifted draftsman. Most of his drawings are contained in the dozens of sketchbooks by him that have survived. The sketches are accompanied by texts, some written backward or in secret ink; they reveal Leonardo to be not only a scientist and engineer but also a mystic. The intellectual, scientific, and artistic interests of the sketchbooks are far-ranging, from stages in the pre-natal development of the human fetus, to the development of flying machines anticipating airplanes, to central-plan architectural plans for churches and cathedrals. This illustration is taken from a page of Da Vinci’s manuscripts and highlights the range of his scientific interests. Leonardo da Vinci still speaks to 21st-century audiences so strongly in part because his mindset seems to anticipate the technology-driven civilization of our own age.

Leonardo da Vinci, Fetus and Lining in the Uterus, ca. 1511–1513, pen and ink with wash over red chalk. By Leonardo da Vinci, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42138639

Mona Lisa

One of the most famous artworks of all time, the Mona Lisa is Leonardo’s masterpiece featuring an enigmatically smiling woman who draws every year millions of visitors to the Louvre. The portrait was revealed by Giorgio Vasari, the first art historian, to depict a wealthy Florentine woman, Lisa di Antonio Maria Gherardini. The Mona Lisa is another example of Leonardo’s use of atmospheric perspective, which is also referred to as sfumato, meaning smoky manner. Sfumato is an Italian word meaning “toned down” or “vanished in smoke.” It is a technique used with particular success by Leonardo. The fame of the Mona Lisa has a lot to do with an event in the Louvre in 1911, when the painting was stolen and eventually recovered two years later. The theft became the first occasion when “art world news” made international headlines.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, ca. 1503–1505, oil on canvas.

Painting in Rome: Michelangelo and Raphael

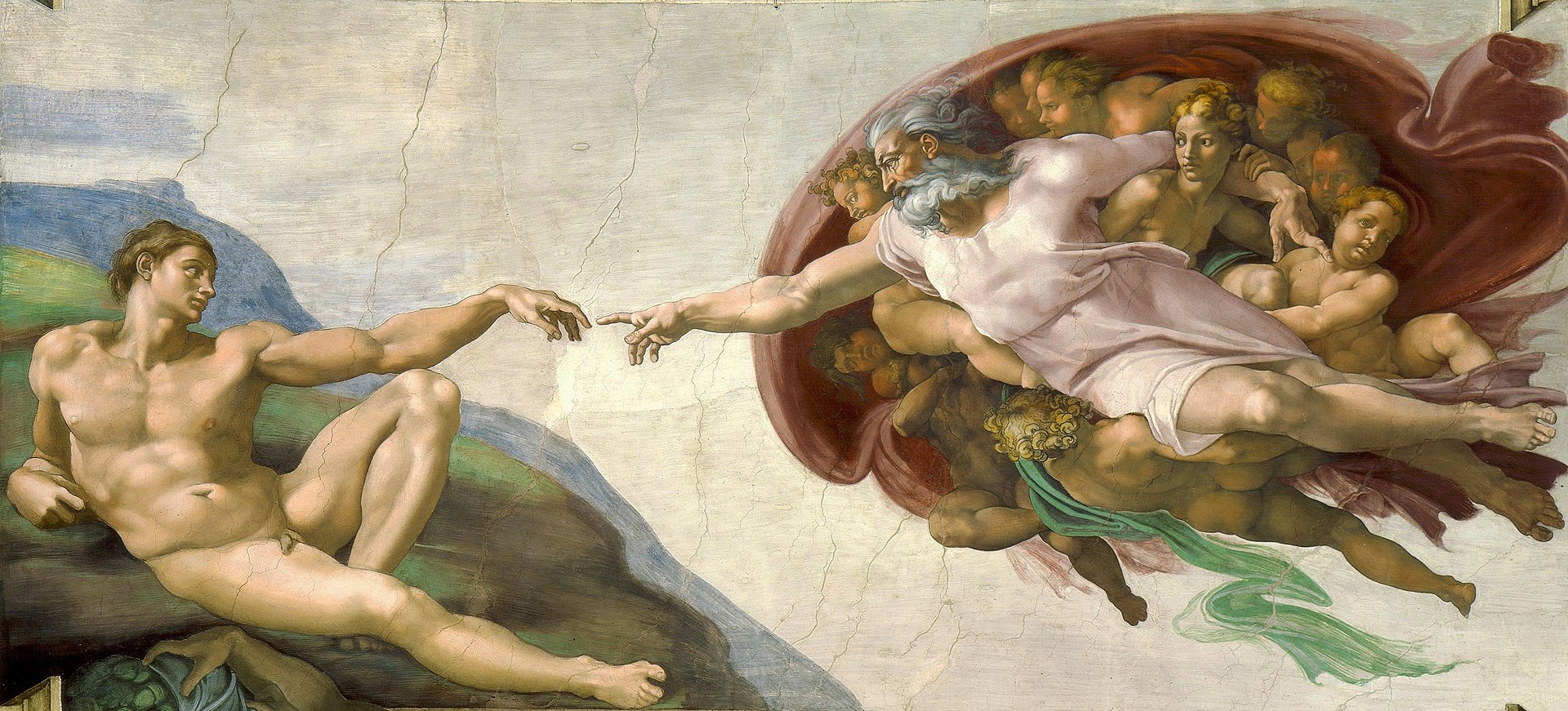

Michelangelo: Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo was a sculptor by training. We will look at his work from three perspectives: painting, architecture, and sculpture. Undoubtedly, his most iconic undertaking was the Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The ceiling was part of a large building program started by Pope Julius II (the “warrior pope”) for the Vatican. Michelangelo at first thought that he was not the right person for the job, but the pope convinced him otherwise. The volumetric, muscular body type that pervades the ceiling is often explained by Michelangelo’s background in sculpture. The Sistine Chapel is of central importance for the life of the Vatican because it is here that new popes are elected by a conclave of cardinals.

There were multiple challenges Michelangelo faced in the fresco’s creation, including its size (5,800 square feet), the curvature of the ceiling, and the distance to the floor (70 feet). The artist had to work from close-up on a scaffold directly under the ceiling, but the effect needed to look just right from 70 feet below. How to maintain visual illusionism? Michelangelo transferred his design on large sheets of paper, where the outlines of the figures were perforated, then the sheets were taken up the scaffold and held up closely against the wall; then charcoal was applied along the perforated outlines, retracing the design directly onto the curving ceiling. The forms were then filled in with the actual painting in the next step.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling unfurls a complex iconographic program. The central strip of panels illustrates the Book of Genesis, showing the Creation, Fall, and Redemption of Humanity. The two central (and most iconic) panels show the Creation of Adam and the Fall from Sin of Adam and Eve. The starting point for the circle is God separating Light and Dark; the end point is the drunkenness of Noah. The panels in the center show Man’s creation (God bringing Adam with a divine spark to life) and Fall from Sin (Adam and Eve being forced to leave Heaven after having tasted the forbidden fruit). To the left and right of the central strip of images, on the side panels, there are seated Hebrew prophets and pagan sibyls. The spandrels (triangular fields above the windows) feature Old Testament figures, such as Moses, David, Judith, and Haman, while above the windows we see Christ’s ancestors.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome, 1508–1512, fresco. By Michelangelo—present version is derived from earlier version, with color cast adjusted; however, this version may appear too blue. CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27931331

Creation of Adam panel. By Michelangelo—see below. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71427942

Raphael: The High Renaissance in Rome

By the early 1500s, the Vatican had turned into a vast treasure house of art. This fresco is from the Stanza della Segnatura, the Room of the Signature in the papal library, where diplomatic treaties were signed. The four walls of the Stanza della Segnatura are decorated with allegorical frescoes representing Theology, Law, Poetry, and Philosophy. They were the work of Raphael and his students. Raphael is the third major artist of the High Renaissance, after Leonardo and Michelangelo. For a long period of time, Raphael, who is best known for Madonna and child images, was the uncontested “art star” of the 18th to the 19th century. But our own age has treated him less kindly because he is often seen as too saccharine (sweet or sentimental). He got demoted by the second half of the 20th century, which made the engineering-minded Leonardo come out ahead of him.

In the Stanza della segnatura, Raphael created Philosophy himself, while the other three wall frescoes were executed by his students. Philosophy is an imaginary gathering of the greatest thinkers from all ages. In the center is Plato (with his book Timaeus) and Aristotle (with his book Nicomachean Ethics). Many ancient philosophers are featured on Plato’s side, and all the sitters in the picture can be identified by name. For example, in the lower right, we see the philosophers Zoroaster and Ptolemy holding globes. Moreover, in the architectural niches in the background, we see marble sculptures of the Greek gods Apollo and Athena. Overall, the work is typical of the infatuation with humanist culture based on classical models, which, by the early 16th century, reached even the Vatican.

Raphael, Philosophy (School of Athens), Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican, Rome, 1509–1511, fresco. By Raphael—Stitched together from vatican.va, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4406048

Michelangelo Revisited: The Sculptural Work

We have encountered Michelangelo before as the painter of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. However, Michelangelo was foremost a sculptor. His David is the epitome of High Renaissance sculpture and a civic monument of Florence. Commissioned by the Cathedral Building Committee after the work on Florence Cathedral was completed, the figure was carved from a single giant block of marble left over from the previous cathedral building campaign. The theme is almost identical to the previous bronze sculptures by Donatello and Verrocchio. Yet Michelangelo’s concept was different in two details. He did not depict an adolescent, but a young man who is vigilant and self-assured in the moment of taking measure of the enemy (Goliath) before he engages in battle. The previous depictions show David after he killed Goliath. The people of Florence strongly associated with David. He was a biblical and a civic hero for them. Michelangelo’s statue was also understood as a political allegory, encouraging Florence and its people to be always watchful, as enemies could be on the prowl.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, David, 1501–1504, marble

Watch the following video on Michelangelo’s David. As you are watching, take notes on the following topics and questions: https://youtu.be/-oXAekrYytA

Michelangelo as an Architect

Michelangelo finished his career as an architect. In 1546 Pope Paul III asked Michelangelo to complete the design and construction of New St. Peter’s after Bramante’s project had been left behind incomplete. Michelangelo started by simplifying Bramante’s central plan: he decided on a Greek cross plan with lateral chapels. For the façade, he opted for a rhythmical and highly ornate staccato of Corinthian pilasters. The aesthetics of the High Renaissance, with their emphasis on measure and simplicity, were abandoned. Stylistically, Michelangelo’s façade of the Vatican marks the transition to Mannerist (late Renaissance) and Baroque (17th-century) architecture. The cupola was finished later by another architect named Giacomo della Porta and was not part of Michelangelo’s design.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Saint Peter’s, Vatican, Rome, 1546–1564

Mannerism

Mannerism, which is synonymous with the Late Renaissance period, celebrates qualities such as artificiality and distorted forms and is furthermore defined by the following characteristics:

- Style of excess and exaggeration

- Renaissance order, symmetry, proportions abandoned

- Elongated figures (figura serpentinata)

- Vertical orientation

- Ambiguous space

- Hyper-sophistication and decadence

Parmigianino: Mannerism

This work, featuring the elongated bodies of Jesus and Mary twisting in space, is the epitome of the Mannerist style. The body parts seem to have lost all proportional relationship with each other: the Madonna’s neck is too long, the Christ child’s head is too big, and his extremities are too long. The body of the Virgin is elongated and twisted, forming a Figura serpentinata, or “serpentine figure.” The setting is imbued with a decadent air of luxuriousness, as expressed through props like curtains, an amphora vase, and a cushion for the Virgin’s throne. The child attendants bringing the amphora are Parmigianino’s invention to enhance the eccentric and decadent aspect of the composition. The free-standing white column of the background alludes to medieval sources, which often compared Mary’s allegedly long neck to a great ivory tower or column. The oddness of the small, emaciated figure of St. Jerome unfurling a scroll (lower right) inspired the Surrealist visions of Spanish painter Salvador Dalí in the 1930s.

Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, ca. 1535, oil on wood

Watch the following video on Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck. As you are watching, take notes: https://youtu.be/suIUUGdNyWk

The development of art and architecture in northern Europe, especially in the Netherlands and Germany, was deeply affected by the Protestant Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries. But even in Catholic countries, like Italy and Spain, the reaction against the Protestant Reformation left its mark in the form of the Baroque style. We can associate, therefore, the art and architecture of the Baroque period—that is, the 17th century, with the so-called Counter-Reformation. In what follows, we will be looking at this evolution from the perspective of painting, sculpture, and architecture.

One of the triggers of the Protestant Reformation was the sale of so-called indulgences to a deeply devout population. Indulgences were pieces of paper granting exemption from time in purgatory in return for a fee paid in cash. Such papers had been in circulation for some time. They were privately printed and offered forgiveness for sins against prayer. Now the Vatican and its agents began selling them to raise money for Pope Julius II. Julius II had financial problems because of warfare, but he was also deeply invested in beautifying the Vatican, which required money.

Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1529

Martin Luther was a clergyman in a provincial part of eastern Germany. He objected strongly to the sale of indulgences, considering the practice corrupt. In 1517, he nailed 95 theses (complaints) to the church door of his hometown in Wittenberg. This started the Protestant movement and the eventual split of the Catholic Church. He was asked to recant but refused on grounds of his consciousness. Luther also translated the Bible into vernacular German. Now laypeople without knowledge of Latin could read it. From a religious point of view, Protestantism stresses personal accountability to God and the punitive consequences of sin and rejects the intercession of saints. Protestant church interiors, in comparison to those of Catholicism, tend to be sparse and do not have much decoration or artworks. The emphasis is on the word, written and spoken, or music, but not on visual representation. A lot of artworks and convents were destroyed during the Reformation. The Bible was upheld as the sole authority on spiritual matters. The Catholic Church launched a counter-offensive to constrain the spread of Protestantism. Among many other measures, the Catholic Council of Trent, in Italy, prescribed that Catholic churches were supposed to have splendid artworks and decorations to overwhelm a mostly illiterate population with visual rhetoric. This gave rise to the art of the Counter-Reformation and to the Baroque style.

The Age of Baroque in Italy

The Baroque style happened mostly during the 17th century, but its influence also extends to the 18th century. The term covers not only art and architecture but also literature and music (Bach, etc.). It is derived from the Portuguese word barroco, meaning an irregularly shaped pearl. It was initially a pejorative term, implying inferiority with respect to the culture of the High Renaissance; such value judgments are no longer implied by the term today. The Baroque put an emphasis on convoluted forms, such as spiral columns, heightened emotionalism, intense religiosity, theatricality, rapture, irrationality, and over-decoration. The style is associated above all with Catholicism and its struggle over a leadership position in Europe. The Baroque style coincides historically with a long series of religious wars and especially the Thirty Years War, 1618–1648. Its approach to art and architecture was defined theoretically by the Council of Trent, 1545–1563, charged with deliberating on counter-measures against Protestantism, which emphasized the use of the rhetorical and propaganda qualities of art to convince believers of the virtues of Catholicism. Naturally, the first place where the Baroque style found application was the Vatican.

Gian Lorenzo BERNINI (1598–1680)

- Good friend of Pope Urban VIII (papacy 1623–1644).

- Erected the bronze Baldacchino over the high altar above St. Peter’s tomb.

- Piazza of St. Peter’s and the Colonnade, representing the embracing arms of Christ.

- His great rival was Francesco Borromini.

- Bernini could make marble turn to flesh.

- His sculptures bend, move, twist and live.

It is rumored that Cardinal Barberini (elected Pope in 1623) held up a mirror so that Bernini could use his self-portrait as David’s face.

Caravaggio: The Invention of Tenebrism

Just as Bernini defined Baroque sculpture, Caravaggio defined Baroque painting. In this scene, he painted the conversation of the Pharisee Saul to St. Paul. Like Bernini, Caravaggio loved to use indirect light sources, situated in his case in night settings, which allowed him to introduce dramatic highlights on the figures. The implication is that a supernatural event is about to take place. The term for night scenes with strong contrasts and indirect light outside of the picture frame is tenebrism (from Italian tenebroso = shadowy manner). It can be associated with Caravaggio and Baroque art.

Caravaggio, Conversion on the Way to Damascus, 1601

Michelangelo Merisi da CARAVAGGIO (1596–1669)

- In 1592, after studying in Milan, he moved to Rome.

- A very troubled man; his violent moods repeatedly landed him in trouble.

- Innovative style used new techniques that influenced painters in Italy, Spain, and northern Europe; called the Caravaggisti.

- Painted to get himself out of trouble and to redeem himself; the sinner asking for salvation.

- Introduced the still life as a painting in its own right, natural (no longer for symbolic significance).

- He used common people and everyday settings in his paintings, like Veronese; genre paintings.

- Calling of St. Matthew, 1599–1600

- Focus on the sinner, not the saint

- Made him popular

Velázquez: Spanish Court Painter

Diego Velázquez was undoubtedly the most famous Spanish Baroque painter. He was the court painter to King Philip IV of Spain and enjoyed the king’s personal confidence. He made one trip to Italy but otherwise stayed in Madrid and attended to his duties as a court painter. Undoubtedly, Velázquez’s most famous work is Las Meninas, or The Maids of Honor. It is a scene from court life in Madrid. We see, on the right, the Infanta, or Princess, Margarita, with her maids-in-waiting (playmates), a dwarf (court jester, for court entertainment), and dogs. The most intuitive interpretation is this: The Infanta watches on as her parents, the king and the queen, are being painted by Velázquez, whom we see in a dark dress with a red cross of the Order of Santiago emblazoned on his chest behind a giant canvas (on the left). The king and queen are reflected in a mirror in the back of the room; in the door frame, we see the court chamberlain. However, we cannot see the subject that Velázquez is painting, but we can infer from the context that it is the portrait of the king and the queen on which he works. An alternative reading may be that he is working on the very same canvas we are currently beholding. Similarly, the picture puts the beholder implicitly in the role of the king and the queen. Understood in this sense, the picture can be interpreted as an interesting document for the formation of modern self-consciousness. The exchange of gazes of the Infanta, her retinue, the king and queen, the painter, and us is one of the moments, according to sociologist Michel Foucault, when the modern subject recognizes his or her human essence.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), 1656, oil o/canvas

Watch the following video on Velázquez’s Las Meninas. As you are watching, take notes on the similarities and differences between Velázquez’s and Caravaggio’s personal Baroque styles:

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1669, oil on canvas, and The Night Watch, 1642, oil on canvas.

The Night Watch

Dutch Baroque Interiors and Still-Life: Vermeer

Vermeer: Dutch Domestic Scenes

The depiction of domestic well-being is also a central concern in the art of Jan Vermeer. Although he is seen today as a major painter of the Dutch “Golden Age,” he was “forgotten” for a long time and was “rediscovered” in the 19th century. He only became a cult artist in the 20th century. We know little about Vermeer’s life, and the number of pictures by him that have come down to us is very limited. He seems to have owned a pub and dealt in art, besides painting himself. One of the defining characteristics of Vermeer’s art is that the views seem slightly out of focus. This property has often been interpreted as evidence for the use of a camera obscura, a primitive viewing device that can serve as an aid for draftsmen. A camera obscura relies on the phenomenon described by physics: if one takes a hermetically sealed box, pierced by a hole on the side, one can observe an upside-down projection of the box’s exterior. A camera lucida takes this idea one step further: a mirror inside the box deflects the projected image upward onto a ground piece of glass, on which tracing paper is placed to record the image. Such devices cannot replace creativity but facilitate the mechanics of drawing. In this example, we see a typical Dutch interior of the 17th century with a tiled floor, paintings on the wall, and curtains.

Vermeer’s art shows the material wealth of middle-class interiors. The spectator is almost an intruder in this domestic harmony. This painting is believed to be an allegorical self-portrait of Vermeer, who depicted himself in the act of painting a picture. He is accompanied by Clio, the muse of history, with her trumpet. In the background, there is a large map of the Dutch Republic; the drawn curtains serve as a spatial divide to the spectator. We see the same “soft focus” typical for Vermeer.

Jan Vermeer, Allegory of the Art of Painting, 1670–1675, oil on canvas

Romanticism: The Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries

Romanticism refers not to a specific style but to an attitude of mind: “A return to natural”; a revival of interest in liberty, power, love, violence, things Greek, medieval, exotic, erotic, and Eastern; and the Romantic dynamism of the struggle between humanity and the untamed forces of nature with a narrative to excite the imagination. Romanticism derives from the romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian) and from the medieval tales of chivalry and adventure.

The Ancient of Days (God Creating the Universe), 1794, is a design by William Blake.

Theodore GÉRICAULT (1791–1824) died at age 33. His work is crucial to the development of Romantic painting, especially in France. He was interested in human psychology, evident in his studies of the insane from 1822 to 1823. Gericault was active in exposing injustice, like in his painting Madwoman with a Mania of Envy. She was a child murderess.

His most famous work was the Raft of the “Medusa,” showing the injustice of promoting the captain of the ship because of his title and connections and not merit. On July 2, 1816, the French frigate Medusa hit a reef off the west coast of Africa. The captain and senior officers boarded 6 lifeboats, saving themselves and some of the more affluent passengers. The remaining 149 passengers and crew were crammed onto a wooden raft, which the captain cut loose from the lifeboat. In 13 days of the raft’s voyage, it became a floating hell of death, disease, mutiny, starvation, and cannibalism. Only 15 people survived. The artist Delacroix was the model for one of the dead bodies.

| Artist | Théodore Géricault |

|---|---|

| Year | 1818–19 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 490 cm × 716 cm (16 ft 1 in × 23 ft 6 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

By Théodore Géricault—Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17456087

Eugene DELACROIX (1798–1863) is the most prominent figure in French Romantic painting. He outlived Géricault by almost 40 years. He was an artist and a writer (he wrote the Journal). His paintings are characterized by broad sweeps of color, lively patterns, and energetic figures.

Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830

-

- Portrays the July 1830 uprising against the Bourbon king Charles X

- The Romantic principles to the revolutionary ideal

- Implying the citizens from all classes have spontaneously taken up arms, united in their goal for liberty

| Artist | Eugène Delacroix |

|---|---|

| Year | 1830 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 260 cm × 325 cm (102.4 in × 128.0 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris[1] |

By Eugène Delacroix—Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives via artsy.net, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27539198

19th Century REALISM

Realism is an artistic movement that emerged in France in the 1840s. Realists rejected Romanticism. During the Industrial Revolution, they revolted against exaggerated emotions, drama, and the exotic subjects of the Romantic movement and instead wanted to portray real and contemporary life and people. The realist works portray people from all classes and walks of life, showing situations depicted in ordinary everyday life. The Industrial Revolution brought new values and criticized social values and the upper class. Realism is generally regarded as the beginning of the modern art movement. It included inventions not seen since Rome, concrete, iron, steam engines, mass communications, railroad, etc., as well as the start of Communism, women’s rights, and reform. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published.

Gustave COURBET (1819–1877) is the French artist most associated with Realism. He believed that artists should represent their own experiences. In 1861, he wrote that art could not be taught but that the artist needed to be inspired by study and observation. When he was asked to paint an angel for the church, Courbet replied, “Show me an angel and I’ll paint one.”

Interior of My Studio 1855—In his words, this painting showed “society at its best, its worse, and its average.” He described the figures on the right as his friends (workers and art collectors). It portrays working-class figures to the upper crust of society. Seated at the far right reading a book is the poet Baudelaire, who was a supporter of Realism.

Gustave Courbet, Interior of My Studio, 1855, oil on canvas, 142×235, Musée d’Orsay.

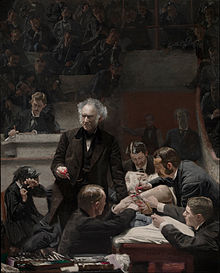

Thomas Cowperthwait EAKINS (1844–1916)

- American Realist painter.

- Eakins was an art teacher and head of the Pennsylvania Academy of art; emphasized figure and anatomy drawing.

- Started allowing women to draw from the nude, which got him into trouble.

- His students started the Students Arts League so he could come teach there when he lost his job at the academy.

Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic, 1875. According to one reviewer in 1876: “This portrait of Dr. Gross is a great work—we know of nothing greater that has ever been executed in America.”

Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic, 1875. According to one reviewer in 1876: “This portrait of Dr. Gross is a great work—we know of nothing greater that has ever been executed in America.”

Henry Ossawa TANNER (1859–1937) is an American painter who moved to Paris and the 1st Black American to exhibit at the Paris Salon. He studied under Thomas Eakins, whose influence had him painting Realist scenes of Black American life in the United States, like his most famous work, The Banjo Lesson.

His mother was born a slave. She moved to Pittsburgh, attended school, and married the Rev. Benjamin Tucker Tanner, who became a bishop. Tanner was sponsored by a patron for a trip to the Middle East in 1897 so he could see the land he wanted to paint in his religious paintings. His Annunciation is one of the best depicted.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Annunciation, 1898. This painting was exhibited at the Salon and shows Mary just awakened by a divine presence. The realistic details like her dress, the stone floor, and Near Eastern rug, combined with mystical qualities of light, are gloriously executed.