4 Chapter 4: Classical Period to Middle Ages

Greece—called themselves the Hellás (this is why as Alexander the Great conquers the known world, he Hellenizes it). Considered the beginning of the civilized world and Western civilization. The height of human development. Some of the ideals we took from the Greeks are city/states, architecture, government, philosophy, math, science, theater, and elections by vote, and the greatest was education for the common man. Chronologically, the beginnings of Greek civilization are contemporary with the cultures in Mesopotamia and Egypt we studied previously. Geographically, the Greeks shared the Mediterranean basin with some of these cultures and absorbed their influences. Ultimately, however, Western civilization owes its formative impulses, above all, to Greece. Before we delve into the beginnings of Western civilization in Greece, let’s clarify the primary time periods in ancient Greece that we will be studying.

Art and Architecture of Pre-Classical Greece (The Aegean period): The introduction of the curved line is one of the most lasting contributions to the art of decoration given to us by the Aegeans.

Minoan culture (ca. 2500–1400 BCE), Crete, named by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evens after the legendary King Minos.

Cycladic culture (ca. 3200–1050 BCE) named for the irregular circles of islands.

Mycenaean culture (ca. 1400–1200 BCE), Agamemnon’s city. Used the corbelled arch mostly in Tholos = tombs.

Art and Architecture of Classical Greece:

Archaic Period (ca. 700–480 BCE). Examples: Kouros and Kore.

Classical Period (ca. 480–323 BCE). A period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BCE). Very timeless and serene. More about the perfection of the male physical form.

Hellenistic Period (ca. 323–30 BCE). The age of Alexander the Great. His rise concludes the transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic Period.

Classical Period Greek Sculpture

The Greeks would eventually achieve a complete and correct understanding of human anatomy and proportions during the Classical period, which culminated around 450–440 BCE. Contributing to this naturalism in sculpture was the knowledge of the principles governing weight shift, or contrapposto (shifting of the main parts of the body around the vertical, but flexible, axis of the spine), in free-standing sculpture. This contrapposto pose is seen in statues throughout the Classical period (and later the Renaissance). The development of a formulaic, idealized canon of human proportions began with works such as the Kritios Boy, from ca. 480 BCE, and culminated in Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (450–440 BCE), which marks the onset of the Early Classical period. The Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, was often cited as a model statue to be imitated by other artists, especially those in training.

Doryphoros (The Spear Bearer) A well-preserved Roman period copy, by Polykleitos, Marble. Height: 6 feet, 11 inches.

Doryphoros (The Spear Bearer) A well-preserved Roman period copy, by Polykleitos, Marble. Height: 6 feet, 11 inches.

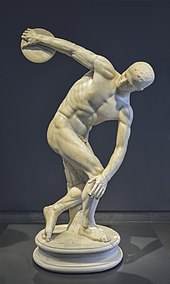

The Discobolos, or Discus Thrower (below), is a highly dramatic sculpture, as the athlete is shown at the moment of just about releasing the discus, when the musculature is at its most tense. The impending release of the energy and of the discus become almost tangible. Romans were great collectors of Greek sculpture and copied or imported such works on a grand scale. Many masterworks of Greek sculpture have survived only in the form of such Roman copies. Telltale signs of a Roman are the “struts” and “trunks” that are meant to support and stabilize the base of the sculptures.

Myron, Discus Thrower/Discobolos, ca. 450 BCE, Roman marble copy after a bronze original.

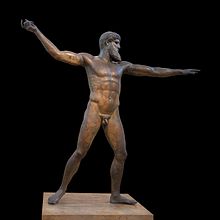

Zeus/Poseidon, Original ancient Greek sculpture. Believed to be Zeus, but when they raised it out of the Mediterranean Sea, people thought it looked like the god Poseidon rising out of the sea. Created by the lost wax method.

The Classical Orders

1. Doric is the 1st order, the most basic, most masculine.

2. Ionic is the 2nd order, elegant, feminine, complex, with tall slender columns. Attached to the Ionic order are the Caryatid (female supporting column) and the Atlas (male supporting column).

3. Corinthian, the 3rd order, is the most elaborate, most elegant, and most extravagant.

The Acropolis, Athens, Greece: Built by Pericles on top of older temples. The four remaining buildings are the Parthenon, the Erechtheum, the Temple of Athena Nike, and the Propylaea. It was badly damaged in 1687 when the Ottomans stored gunpowder in the Parthenon and a cannonball hit the pile and it exploded.

By David Garnand – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35169845

Hellenistic Period

Following the Classical Period, the Hellenistic Period (323–30 BCE) saw a decline of the ideals espoused by the age of Pericles and Phidias. Athenian dominance in Greece came to an end with a disastrous defeat of the Athenians during the Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE and the subsequent subjection by Philip of Macedon. Philip hailed from Macedonia, a territory to the north of Greece. It was an epoch of civil wars and social and political unrest. As a result of these events, the traditional balance between the city-state and the individual was lost.

Philip’s son, Alexander the Great, set out to conquer most of the Near and Middle East, including Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, Assyria, Persia, and even parts of India. The city of Alexandria, in the north of Egypt and famous for the library established there by Alexander the Great, is named after him. Therefore, the period of Alexander’s rule saw an influx and subsequent absorption of Eastern cultural and artistic influences by Greek artists (and vice versa).

Drastic changes in Greek art, henceforth called Hellenistic, came about and emphasized the following: Departure from the Classical canon of idealized human beauty, drama, violence, suffering, age, and physical decay became the focus of interest of Hellenistic artists. Nude female figures emerged as a subject for sculpture.

Winged Victory or Winged Nike from Samothrace ca. 200–190 BCE, marble. One of the few Hellenistic originals, not a Roman copy. Located at the Louvre museum. It was found on the island of Samothrace in pieces and put back together. Arms and head are still missing. Nike means victory.

Laocöon group. There is nothing more quintessentially Hellenistic than the Laocöon group, sculpted by Agesander, Athenodorus, and Polydorus in the early 1st century BCE. It is the pinnacle of late classical Greek (= Hellenistic) sculpture. The violent scene depicts three muscular male figures attacked by serpents. Its story was derived from a myth dating to the times of the Trojan War, which was related by the Roman author Virgil. Laocöon was a Trojan priest. The Greeks were laying siege to Troy and crafted a Trojan horse to gain access to the enemy city. Laocöon warned his fellow Trojan citizens of the Greeks’ ruse, but the gods (Apollo, Poseidon, or Hera) sided with the Greeks and sent sea serpents to exact revenge on the priest and his two sons. We hence see them in the process of being strangled by sea serpents. The depiction of pain and writhing figures is typical for Hellenistic art, as exemplified in this group. It is a Roman copy (the Romans copied many of the bronzed Greek works in marble; most of the bronzed pieces were melted down). The original was most likely done in bronze and was melted down.

Agesander, Athenodorus, and Polydorus, Laocöon, early 1st century BCE (?), marble

Watch the following video on the Laocöon and His Sons:

https://youtu.be/C3cwGCezgSQ

The Roman period—Known as the Latins. Rome was founded in 753 BCE and remained a monarchy until 509 BCE, when the last of the Roman kings was expelled and the territory became a republic. Rome was a republic for over 500 years until Julius Caesar. Subsequent expansion catapulted Rome from a regional power to, ultimately, a world power. Neighboring tribes were subjugated, and both Greek settlers (in the south) and Etruscans (in the north) were absorbed into the Roman populace. Rome’s greatest strength was absorbing other cultures and making them their own and building them on a grander scale (example: arches and aqueducts). The ancient Romans contributed greatly to the development of law, art (copied many of the Greek works), engineering, literature, architecture, technology, and much more. Take a look at the animated map of the Roman Empire from 500 BCE to the fall of the last Byzantine successor state of Rome to see the territorial expansion and loss of the empire.

Pompeii

A lot of our knowledge about daily life in Republic Rome comes from the town of Pompeii and neighboring Herculaneum, which were preserved under a thick layer of ashes following a major volcanic eruption of Mt. Vesuvius on August 24, 79 CE. A vivid account by writer Pliny the Younger tells us of a catastrophe that resulted in major loss of life; afterward Pompeii ceased to exist. Some of the volcanic dust from the eruption was later found as far away as Iceland.

Pompeii was rediscovered in the mid-18th century and gradually excavated. Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum fascinated 18th- and 19th-century artists and writers. The volcanic eruption preserved both commercial (small shops, offices, taverns, etc.) and residential sections of Pompeii, including a number of upscale private villas like the one below, richly decorated with frescoes.

The House of the Vettii is a typical example of a Pompeian town house with an atrium (i.e., an open courtyard), and an opening in the roof (compluvium). The frescoes are an example of the “Pompeian Fourth Style”: we find a mixture of narrative panels, trompe-l’oeil (means “trick of the eye” in French), architectural vistas, and stone imitation paneling. A possible influence was Roman theater design. Pompeian fresco paintings can be very sexually explicit: in the entrance foyer of this house, there is the life-size depiction of Priapus, the god of fertility, protector of horticulture and viticulture.

House of the Vettii, Pompeii, frescoes completed between 62 and 79 CE.

Imperial Rome

The Mediterranean Sea became known as the Roman lake, as Rome controlled all the land surrounding it. Roman art was more naturalistic and less stylized than Greek art. Romans were more interested in realism; Greeks were more interested in idealism.

The last years of Republican Rome were riddled with civil wars, which Octavian Caesar, the future Emperor Augustus, ended after defeating Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE. There followed a period called “Pax Romana” (“Roman Peace”), which lasted for about 150 years, during which Rome was ruled by a long line of emperors, the Julio-Claudians.

This time period was characterized by efforts to glorify the outer aspects of the empire with an emphasis on building public works, architecture, and infrastructure designed primarily to impress (propaganda) and to serve the needs of the living (utilitarian).

During the 2nd century, Rome was at the height of its power. Under the emperors Trajan, Hadrian, and the Antonines, Rome reached its largest geographical expansion, from Britain to Egypt and Mesopotamia (see the map above showing the reach of the Roman Empire in 117 CE).

Starting in the 3rd century, tribes coming mostly from the northern fringes of the empire (Goths, Vandals, etc.) launched incursions that damaged the economic and administrative structures of Rome. These problems were magnified by mentality changes (e.g., emerging anti-materialism) from inside the empire, brought about by the introduction of Christianity, which had graduated from persecuted mystery cult, to toleration under Constantine the Great in 313, to official state religion in 380. At this point, the Roman Empire was on the verge of collapse, followed by a division into an eastern and western empire and the beginning of the Byzantine era in 395.

The Colosseum

The Colosseum is an example of an amphitheater, a Roman invention that consists of two semi-circular theaters enclosing an oval arena with a movable sun cover. The name derives from a giant (“colossal”) statue of Nero in front, which has since vanished. It stands out as a prime example of a public works monument destined to serve the general public. It was built on top of Nero’s pleasure lake by Emperor Vespasian (69–79 CE) and was completed in 80 CE by his successor, Titus. The Colosseum has 80 entrances. One door, the Porta Libitina, was used to bring out the dead; a second door, Sanivivaria, was used by victors & survivors; the third and fourth doors were for the emperor’s use. Events were held from sunrise to sunset (usually), starting with a procession that ended with riders saluting the emperor, followed by fantasy or comic fights, then blood sports and beast hunts, and ending with the executions. Furthermore, at inauguration, a mock naval battle was staged with 3,000 participants, and the arena was flooded on purpose to hold naval ships.

Colosseum, Rome, 70–82. By FeaturedPics – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95579199

Interior of the Colosseum, Rome, 70–82. By Jean-Pol GRANDMONT – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17071408

The Pantheon, Rome (original ca. 27 BCE–14 CE) Rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian (ca. 126 CE) The Pantheon is the best preserved and oldest ancient Roman building still in use today. After two thousand years, this dome is still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

By Rabax63 – File:Pantheon_Rom_1.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=87626466

The Pantheon, inside view.

Arch of Constantine 312–315 CE, triumphal arch in Rome. The arch commemorates Emperor Constantine’s victory in the civil war that left him as the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

The Middle Ages

The transition from the classical to the medieval world was gradual and took place over many years. An important turning point was the introduction of Christianity. Therefore, Early Medieval, Late Roman, and Late Classical are mostly interchangeable terms as far as our time frame is concerned.

Pagan (pre-Christian) Rome was polytheistic (believed in many gods); Christianity is monotheistic (there is but one God). Constantine the Great recognized Christianity as a tolerated religion, but only his successor, Theodosius, made it the official religion of the state.

In 395, the empire was divided again into an eastern (pars orientis) and a western half (pars occientalis), this time for good. The eastern half, with Constantinople (today Istanbul) as its capital, will take the name of the Byzantine Empire. The decline was less pronounced in the eastern (Byzantine) half of the empire than in the western half, but everywhere the population was declining, farms were abandoned, skills were lost, and infrastructure was no longer maintained. In the western half, the decline culminated in the sack of Rome in 410 by the Goths.

Note how the division of the Roman Empire still informs the different “flavors” of Christianity to the present day:

- Eastern Empire = Byzantium = Orthodox faith

- Western Empire = Rome (mostly) = Roman Catholic faith

Byzantine culture, after the permanent division of 395, returned to Greek language and traditions. It mixed Roman civilization with the “orientalizing” influences of the Near East. In the 8th and 9th centuries, there was an iconoclastic controversy (iconoclasm = image smashing) in Byzantium, which had theological and political dimensions that most notably led to the wide destruction of visual art. The Iconoclasts opposed the worship of saints and destroyed such images wherever possible. Although ultimately the icon worshippers (Iconophiles) won out, a lot of artworks were destroyed during these years. Beginning in the 7th century, the rise of Islam, expanding from the Arabian Peninsula, created a political, military, and religious challenge to the Byzantine Empire to which it will ultimately succumb. It should be noted that Islam, too, rejected figurative art.

Catacombs

Prior to the toleration of Christianity under Constantine, Christians were frequently persecuted by the Roman authorities. In those times, they found refuge in the catacombs, a maze-like system of underground funerary sites excavated from granular tufa (a soft, volcanic rock). Within the catacombs, there were galleries connecting to small rooms (cubicula) filled with funerary niches (loculi). Conditions were unsanitary (dead bodies!), but nevertheless, the Christian community prevailed and celebrated services here.

Some Christian catacombs can be identified as such because of their fresco decoration, as seen in the ceiling from the Catacomb of Saints Pietro and Marcellinus, Rome, from the 4th century. The quality of the frescoes is not at the level of those of Pompeii, but for the first time we see a specifically Christian iconography emerging. Christ is depicted as the Good Shepherd (here, in the central medallion), surrounded by figures in “orants” (attitude of prayer, with outstretched arms) poses on the margins.

Gallery and luculi (funerary niches) of early Christian Catacombs, Rome, 3rd century

Christ the Good Shepherd, Catacomb of Saints Pietro and Marcellinus and catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, 4th century, fresco.

Islamic Architecture

In 1453, Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, fell to the Muslim army of Mehmet II the Conqueror. The Byzantine Empire came to an end. However, Islam had been on the rise for centuries before this event. Prophet Mohammed lived between 570 and 632 in what is today Saudi Arabia, where he taught at Mecca and Medina. Soon, his teachings spread across the Arabian Peninsula and from there to most of the Middle East and northern Africa. Between 711 and 1492, parts of Spain came under Moorish (Islamic) domination until the area reverted back to Catholicism.

The foremost type of architecture we can associate with Islam is the mosque, the place of worship for the followers of Islam. Every mosque must have a minaret, or tower to call the believers for prayer, and a mihrab, or prayer niche, indicating the direction of Mecca to which all participants in communal prayer must turn.

Mihrab within the Mosque at Cordoba

The Mosque at Cordoba in Spain dates from the Moorish (Islamic) period of Spanish history mentioned above. Although no longer used as a mosque today—it was rededicated a Christian church in the 13th century—it is a particularly splendid example of mosque architecture. The Mosque at Cordoba retains the typical large prayer hall and a mihrab with a richly patterned mosaic inside. It is different from other such structures because of its unique system of double-tiered arches of polychrome (multi-colored) stone, where one arch is stacked upon another arch. This feature has been attributed to the combination of local Spanish and Moorish (Muslim) influences.

Byzantine Art

During the early medieval period, the focus of innovative artistic and architectural activity thus shifted from Rome to Constantinople. Constantinople was a wealthy city, which offered all the amenities, such as theaters, hippodromes, a water supply system, etc., that Rome provided. Since its refounding dated to the onset of Christian times, Christian monuments, such as churches, cathedrals and convents, dominated the appearance of the city. Many of these artistic and architectural riches were dispersed or destroyed, first, during the sack of Constantinople at the 4th Crusade and, later, after the 15th-century Islamic conquest.

Because of political turmoil, incursions, and military instability, small, hand-held objects, like ivory carvings, were artworks of choice during the Middle Ages. Byzantium was no exception. The Diptych below featuring the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I is an example of such a small object and was carved out of ivory. A Diptych is a term that describes an object consisting of two hinged panels. (What then is a triptych? A three-paneled artwork.) Despite its religious appearance, the Diptych of Anastasius I was a secular artwork. Anastasius I was a Byzantine emperor who ruled between 491 and 518. In this depiction, he is sitting on a throne and about to throw a handkerchief (mappa), the sign to let the games begin (like in Rome, there were amphitheaters and hippodromes in Constantinople; the games were presided over by the emperor).

Byzantine Architecture

Hagia Sophia

Of course, there would have been an infinitely larger number of cathedrals, churches, convents, and artworks in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, than in Ravenna. While the western half of the empire disintegrated under the pressure of invasions, the Byzantine east and its capital Constantinople prospered. The monumental church of Hagia Sophia (meaning “Holy Wisdom”) epitomizes Byzantine power and splendor. Hagia Sophia was built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, who was also responsible for large territorial expansions and who compiled a codex of civil law, which formed the basis of jurisprudence in Western civilization.

Watch the following video on the Byzantine Hagia Sophia. As you are watching, take notes of the following questions and topics: https://youtu.be/XfpusWEd2jE

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532–537

St. Mark’s Cathedral

Models and innovations of Byzantine builders echoed back to Italy and resonated especially in Venice because of the lagoon city’s close Oriental contacts. St. Mark’s Cathedral, located on Venice’s central square, is an early example of this Byzantine influence. Although it was built and modified over many centuries (as most great buildings are), Romanesque and Gothic additions hide a Byzantine core. It features a Greek-cross plan (all extremities of the cross are of equal length) and a cluster of four domes resting on pendentives, just like in the Hagia Sophia. The interior features rich gold-ground mosaics, which are typical of Byzantine art, telling key stories from the Old and New Testaments. The jewel-like, gilded interior of St. Mark’s gives us an idea of what the Hagia Sophia may have looked like before the Islamic conquest.

St. Mark’s Cathedral, Venice, begun 1063