7 Music of the Baroque Period

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the historical and cultural contexts of the Baroque period.

- Identify musical performing forces (voices, instruments, and ensembles), styles, composers, and genres of the Baroque.

- Describe ways in which music and other influences interact in music of the Baroque period.

- Identify selected music of the Baroque, making critical judgments about its style and use.

From Understanding Music: Past and Present

By Jeff Kluball and Elizabeth Kramer

Edited by Steven Edwards and Bonnie Le

Introduction and Historical Context

This brief introduction to the Baroque period is intended to provide a short summary of the music and context of the Baroque era, which lasted from about 1600 to 1750.

The term “Baroque” has an interesting and disputed past. Baroque ultimately is thought to have derived from the Italian word barocco, referring to a contorted idea, obscure thought, or anything different, out of the ordinary, or strange. Another possible origin is from the Portuguese term barrocco, in Spanish barrueco. Jewelers still use this term today to describe irregular or imperfectly shaped pearls: a baroque pearl. The Baroque period is a time of extremes resulting from events stemming back to the Renaissance. The conflict between the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and the influence of Greek/Roman culture as opposed to medieval roots are present throughout the Baroque era.

In art circles, the term baroque came to be used to describe the bizarre, irregular, or grotesque or anything that departed from the regular or expected. This definition was adhered to until 1888, when Heinrich Woolfflin coined the word as a stylistic title or designation. The baroque title was then used to describe the style of the era. The term “rococo” is sometimes used to describe art from the end of the Baroque period, from the mid to late eighteenth century. The rococo took the extremes of baroque architecture and design to new heights with ornate design work and gold gilding. Historical events and advances in science influenced music and the other arts tremendously. It is not possible to isolate the trends of music during this period without briefly looking into what was happening at the time in society.

Baroque Timeline

- 1597: Giovanni Gabrieli writes his Sacrae Symphoniae

- 1607: Monteverdi performs Orfeo in Mantua, Italy

- 1618-1648: Thirty Years War

- 1623: Galileo Galilei publishes The Assayer

- 1642-1651: English Civil War

- 1643-1715: Reign of Louis XIV in France

- 1649: Descartes publishes Passions of the Soul

- 1678: Vivaldi born in Venice, Italy

- 1685: Handel and Bach born in Germany

- 1687: Isaac Newton publishes his Principia

- 1740-1786: Reign of Frederick the Great of Prussia

- 1741: Handel’s Messiah performed in Dublin, Ireland

- 1750: J. S. Bach dies

Music in the Baroque Period

Music Comparison Overview

| Renaissance Music | Baroque Music |

|---|---|

| Much music with rhythms indicated by musical notation | Meter more important than before |

| Mostly polyphony (much is imitative polyphony) | Use of polyphony continues |

| Growing use of thirds and triads | Rise of homophony; rise of instrumental music, including the violin family |

| Music–text relationships increasingly important with word painting | New genres such as opera, oratorio, concerto, cantata, and fugue |

| Invention of music publishing | Emergence of program music |

| Growing merchant class increasingly acquires musical skills | First notation of dynamics and use of terraced dynamics |

| Continued presence of music at church and court | |

| Continued increase of music among merchant classes |

Science

Sir Isaac Newton and his studies made a great impact on Enlightenment ideology. In addition to creating calculus, a discipline of mathematics still practiced today, he studied and published works on universal gravity and the three laws of motion. His studies supported heliocentrism, the model of the solar system’s planets and their orbits with the sun. Heliocentrism invalidated several religious and traditional beliefs.

Johannes Kepler (b. 1571-1630), a German astronomer, similarly re-evaluated the Copernican theory that the planets move in a circular motion in their orbits around the sun. In utilizing Brahe’s records, Kepler concluded that the planets move in ellipses in their orbits around the sun. He was the first to propose elliptical orbits in the solar system.

William Harvey conducted extensive anatomical research concerning the circulatory system. He studied the veins and arteries of the human arm and also concluded that the blood vessel system is an overall circle returning back to the heart while passing through the lungs.

Philosophy

René Descartes (1595-1650) was a famous philosopher, mathematician, and scientist from France. His opinions on the relationship of the body and mind as well as certainty and knowledge have been very influential. He laid the foundation for an analysis and classification of human emotions at a time when more and more writers were noting the powers of music to evoke emotional responses in their listeners.

John Locke (1632-1704) is regarded as the founder of the Enlightenment movement in philosophy. Locke is believed to have originated the school of thought known as British Empiricism, which laid the philosophical foundation for the modern idea of limited liberal government. Locke believed each person has “natural rights,” that government has obligations to its citizens, that government has very limited rights over its citizens, and that in certain circumstances, it can be overthrown by its citizens.

Art

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) was a famous Italian sculptor of the Baroque era. He is credited with establishing the Baroque sculpture style. He was also a well-known architect and worked most of his career in Rome. Although he enjoyed the patronage of the cardinals and popes, he challenged artistic traditions.

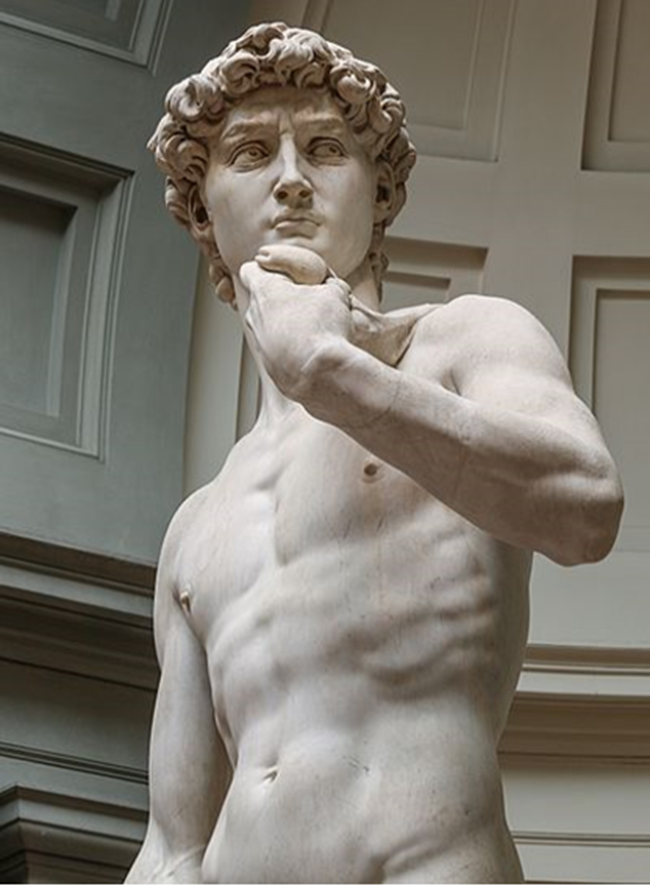

His art reflects a certain sense of drama, action, and sometimes playfulness. Compare, for instance, his sculpture of David (1623-1624) with the David sculpture (1501-1504) of Renaissance artist Michelangelo.

Where Michelangelo’s David appears calmly lost in contemplation, Bernini’s David is in the act of flinging his slingshot, jaw set and muscles tensed. We see similar psychological intensity and drama in music of the Baroque period.

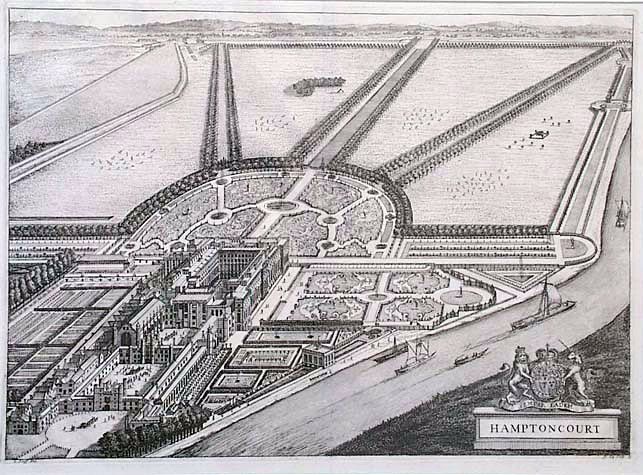

Elaborate formal Baroque gardens indicating man’s control over nature were used to demonstrate the owner’s power and prestige. France was a major contributor to the development of these highly ornamental gardens. These gardens became associated with autocratic government. The designs of these elaborate gardens were from “Cartesian” geometry (science and mathematics) while drawing the landscape into the composition. Look at the Leonard Knyff engraving of the Hampton Court Baroque garden.

Literature

Literature during the Baroque period often took a dramatic turn. William Shakespeare (1564-1616), playwright and poet, wrote the play Hamlet and many other great classics still enjoyed by millions of readers and audiences today. Music composers have long used Shakespeare’s writing for text in their compositions; for example, his Hamlet was used as the basis for an opera. Shakespeare’s writings depict an enormous range of human life, including jealousy, love, hate, drama, humor, peace, intrigue, and war, as well as all social classes—matter that provides great cultural entertainment.

Jean Racine (1639-1699) wrote tragedies in the neoclassic (anti-Baroque) and Jansenism literary movements. Many works of the classical era utilized rather twisted, complicated plots with simple psychology. Racine’s neoclassic writing did just the opposite, incorporating simple and easy-to-understand plots with challenging uses of psychology. Racine is often grouped with Corneille, known for developing the classic tragedy form. Racine’s dramas portray his characters as human with internal trials and conflicting emotions. His notable works include Andromaque, Phèdre, and Athalie.

Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. Don Quixote is his most famous work and is often considered the first modern novel from Europe. It was published in 1605 and portrays the traditions of Sevilla, Spain. Legend has it that the early portions of Don Quixote were written while the author was in jail for stealing.

Other Baroque-era authors include John Milton (1608-1674), author of the epic Paradise Lost; John Dryden (1631-1700), dramatist and poet who wrote several semi-operatic works incorporating music by contemporary composer Henry Purcell; Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), an Anglo-Irish essayist and proto-novelist, poet, and cleric who authored Gulliver’s Travels; and Henry Fielding (b. 1707-1754) a proto-novelist and dramatist who authored Tom Jones.

We will find a similar emphasis on drama as we study Baroque music, especially in the emergence of genres such as opera and oratorio.

Politics

In politics, three changes that started in the Renaissance became defining forces in the Baroque period. First, nation-states (like France and England) developed into major world powers ruled by absolutist monarchs. These absolute monarchs were kings and queens whose authority, it was believed, was divinely bestowed upon them. They amassed great power and wealth, which they often displayed through their patronage of music and the other arts. With the rise of this system of absolutism, the state increasingly challenged the power base of the church. In the case of Germany, these nation-states were smaller and often unstable. Second, Protestantism spread throughout northern Europe. Places such as England, where Georg Frideric Handel spent most of his adult life, and central Germany, where Johann Sebastian Bach spent all of his life, were Protestant strongholds. J. S. Bach wrote a great deal of music for the Lutheran Church. Third, the middle class continued to grow in social and economic power with the emergence of printing and textile industries and open trade routes with the New World (largely propelled by the thriving slave trade of the time).

Exploration and Colonialism

The 1600s saw the first era of the colonization of America. France and England were the most active in the colonization of America. The quest for power in Europe, wealth/economics and religious reasons energized the colonial progression. Hudson explored the later-named Hudson River (1609); Pilgrims landed at Plymouth (1620); Manhattan was bought from Native Americans (1626); Boston was founded (1630); and Harvard University was founded (1636).

General Trends of Baroque Music

The characteristics highlighted in the chart above give Baroque music its unique sound and appear in the music of Monteverdi, Pachelbel, Bach, and others.

To elaborate:

- Instrumental solo music was composed with a major emphasis on violin and keyboard compositions.

- Definite and regular rhythms in the form of meter and “motor rhythm” (the constant subdivision of the beat) appear in most music. Bar lines become more prominent.

- The use of polyphony continues with more elaborate techniques of imitative polyphony used in the music of Handel and Bach.

- Homophonic (melody plus accompaniment) textures emerge, including the use of basso continuo (a continuous bass line over which chords were built used to accompany a melodic line).

- Homophonic textures lead to increased use of major and minor keys and chord progressions (see chapter 1).

- The accompaniment of melodic lines in homophonic textures is provided by the continuo section: a sort of improvised “rhythm section” that features lutes, viola da gambas, cellos, and harpsichords. Continuo sections provide the basso continuo (continuous bass line) and are used in Baroque opera, concerti, and chamber music.

- Instrumental music featuring the violin family—such as suites, sonatas, and concertos emerge and grow prominent.

- These compositions are longer, often with multiple movements that use defined forms having multiple sections, such as ritornello form and binary form.

Genres of the Baroque Period

Much great music was composed during the Baroque period, and many of the most famous composers of the day were extremely prolific. To approach this music, we’ll break the historical era into the early period (the first seventy-five years or so) and the late period (from roughly 1675 to 1750). Both periods contain vocal music and instrumental music.

The main genres of the early Baroque vocal music are madrigal, motet, and opera. The main genres of early Baroque instrumental music include the canzona (also known as the sonata) and suite. The main genres of late Baroque instrumental music are the concerto, fugue, and suite. The main genres of late Baroque vocal music are Italian opera seria, oratorio, and the church cantata (which was rooted in the Lutheran chorale, already discussed in the chapter on the Renaissance, “Music of the Protestant Reformation”). Many of these genres will be discussed later in the chapter.

Solo music of the Baroque era was composed for all the different types of instruments but with a major emphasis on violin and keyboard. The common term for a solo instrumental work is a sonata. Please note that the non-keyboard solo instrument is usually accompanied by a keyboard, such as the organ, harpsichord, or clavichord.

Small ensembles are basically named in regard to the number of performers in each (trio = three performers, etc.). The most common and popular small ensemble during the Baroque period was the trio sonata. These trios feature two melody instruments (usually violins) accompanied by basso continuo (considered the third single member of the trio).

The large ensembles genre can be divided into two subcategories, orchestral and vocal. The concerto was the leading form of large ensemble orchestral music. Concerto featured two voices, that of the orchestra and that of either a solo instrument or a small ensemble. Throughout the piece, the two voices would play together and independently, through conversation, imitation, and in contrast with one another. A concerto that pairs the orchestra with a small ensemble is called a concerto grosso, and a concert that pairs the orchestra with a solo instrument is called a solo concerto.

The two large vocal/choral genres for the Baroque period were sacred works and opera. Two forms of the sacred choral works include the oratorio and the mass. The oratorio is an opera without scenery or acting.

The Mass served as the core of the Catholic religious service and commemorates the Last Supper. Opera synthesizes theatrical performance and music. Opera cast members act and interact with each other. Types of vocal selections utilized in an opera include recitative and aria. Smaller ensembles (duets, trios, etc.) and choruses are used in opera productions.

| Oratorio | Opera Seria | Cantata |

|---|---|---|

| Similar to opera except no costumes or staging | Serious opera | A work for voices and instruments |

| A lot of choral numbers | Historical or mythological plots | Either sacred, resembling a short oratorio, or secular as a lyrical drama set to music |

| Typically on biblical topics | Lavish costumes and spectacular sets | Sacred cantata often involve church choirs and are not acted out |

| Vocal soloist performs in front of accompanying instruments | Showcased famous solo singers | Can include narration |

| Examples of biblical oratorios: Handel’s Saul, Solomon, and Judas Maccabeus | All sung; no narration | Example: Bach’s famous Reformation Cantata BWV 80: Ein feste Burg ist unser Got (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) |

| Non-biblical examples: Handel’s Hercules, Acis and Galatea, and The Triumph of Time and Truth | Acted and performed on stage | |

| Examples: L’Ofeo, L’Arianna, The Fairy Queen (based on Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream), and Ottone in Villa |

Birth of Opera

The beginning of the Baroque period is in many ways synonymous with the birth of opera. Music drama had existed since the Middle Ages (and perhaps even earlier), but around 1600, noblemen increasingly sponsored experiments that combined singing, instrumental music, and drama in new ways. As we have seen in a previous section, Renaissance Humanism led to new interest in ancient Greece and Rome. Scholars as well as educated noblemen read descriptions of the emotional power of ancient dramas, such as those by Sophocles, which began and ended with choruses. One particularly active group of scholars and aristocrats interested in the ancient world was the Florentine Camerata, so called because they met in the rooms (or camerata) of a nobleman in Florence, Italy. The Florentine Camerata were a group of musicians and scholars who “invented” opera while trying to recreate the spirit of Greek drama. This group, which included Vicenzo Galilei, father of Galileo Galilei, speculated that the reason for ancient drama’s being so moving was its having been entirely sung in a sort of declamatory style that was midway between speech and song. Although today we believe that actually only the choruses of ancient drama were sung, these circa 1600 beliefs led to collaborations with musicians and the development of opera. Basically, opera was sung secular dramas that features elaborate staging and costumes.

Less than impressed by the emotional impact of the polyphonic church music of the Renaissance, members of the Florentine Camerata argued that a simple melody supported by sparse accompaniment would be more moving. They identified a style that they called recitative, in which a single individual would sing a melody line that follows the inflections and rhythms of speech. The recitative was a type of singing speech that served as the dialogue of the opera. It was rhythmically free allowing the music to follow the text being sung to make it easy for the audience to understand the story being told. This individual would be accompanied by just one or two instruments: a keyboard instrument, such as a harpsichord or small organ, or a plucked string instrument, such as the lute. The accompaniment was called the basso continuo.

Basso continuo is a continuous bass line over which the harpsichord, organ, or lute added chords based on numbers or figures that appeared under the melody that functioned as the bass line. The basso continuo part performed by the keyboard and bass instrument (like a cello) placed emphasis on the bass line. It would become a defining feature of Baroque music. This system of indicating chords by numbers was called figured bass and allowed the instrumentalist more freedom in forming the chords than had every note of the chord been notated. This figured bass was a type of musical shorthand played by the basso continuo part. The flexible nature of basso continuo also underlined its supporting nature. The singer of the recitative was given license to speed up and slow down as the words and emotions of the text might direct, with the instrumental accompaniment following along. This method created a homophonic texture, which consists of one melody line with accompaniment, as you might recall from earlier chapters.

Composers of early opera combined recitatives with other musical numbers such as choruses, dances, arias, instrumental interludes, and the overture. The choruses in early Baroque opera were not unlike the late Renaissance madrigals that we studied earlier. Operatic dance numbers used the most popular dances of the day, such as pavanes and galliards. Instrumental interludes tended to be sectional—that is, having different sections that sometimes repeated, as we find in other instrumental music of the time. Operas began with an instrumental piece called the Overture.

Like recitatives, arias were homophonic compositions featuring a solo singer over accompaniment. Arias, however, were less improvisatory. The melodies sung in arias almost always conformed to a musical meter, such as duple or triple, and unfolded in phrases of similar lengths. As the century progressed, these melodies became increasingly difficult or virtuosic. If the purpose of the recitative was to convey emotions through a simple melodic line, then the purpose of the aria was increasingly to impress the audience with the skills of the singer.

Opera was initially commissioned by Italian noblemen, often for important occasions such as marriages or births, and performed in the halls of their castles and palaces. By the mid to late seventeenth century, opera had spread not only to the courts of France, Germany, and England but also to the general public, with performances in public opera houses first in Italy and later elsewhere on the continent and in the British Isles. By the eighteenth century, opera would become as ubiquitous as movies are for us today. Most Baroque operas featured topics from the ancient world or mythology, in which humans struggled with fate and in which the heroic actions of nobles and mythological heroes were supplemented by the righteous judgments of the gods. Perhaps because of the cosmic reaches of its narratives, opera came to be called opera seria, or serious opera. Librettos, or the words of the opera, were to be of the highest literary quality and designed to be set to music. Italian remained the most common language of opera, and Italian opera was popular in England and Germany; the French were the first to perform operas in their native tongue.

Focus Composition: “Tu se morta” (“You are Dead”) from Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607)

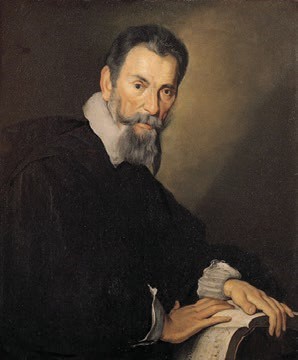

One of the very first operas was written by an Italian composer named Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643; see Figure 7.4). For many years, Monteverdi worked for the Duke of Mantua in central Italy. There he wrote Orfeo (1607), an opera based on the mythological character of Orpheus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In many ways, Orpheus was an ideal character for early opera (and indeed many early opera composers set his story): he was a musician who could charm with the playing of his harp not only forest animals but also figures from the underworld, from the river-keeper Charon to the god of the underworld Pluto. Orpheus’s story is a tragedy. He and Eurydice have fallen in love and will be married. To celebrate, Eurydice and her female friends head to the countryside, where she is bitten by a snake and dies. Grieving but determined, Orpheus travels to the underworld to bring her back to the land of the living. Pluto grants his permission on one condition: Orpheus shall lead Eurydice out of the underworld without looking back. He is not able to do this (different versions give various causes), and the two are separated for all eternity.

One of the most famous recitatives of Monteverdi’s opera is sung by Orpheus after he has just learned of the death of his beloved Eurydice. The words of his recitative move from expressing astonishment that his beloved Eurydice is dead to expressing his determination to retrieve her from the underworld. He uses poetic images referring to the stars and the great abyss before, in the end, bidding farewell to the earth, the sky, and the sun in preparation for his journey.

As recitative, Orpheus’s musical line is flexible in its rhythms. Orpheus sings to the accompaniment of the basso continuo, here just a small organ and a long-necked Baroque lute called the theorbo, which follows his melodic line, pausing where he pauses and moving on where he does. Most of the chords played by the basso continuo are minor chords, emphasizing Orpheus’s sadness. There are also incidents of word painting, the depiction of specific images from the text by the music.

Whether you end up liking “Tu se morta” or not, we hope that you can hear it as dramatic, as attempting to convey as vividly as possible Orpheus’s deep sorrow. Not all the music of Orfeo is slow and sad like “Tu se morta.” In this recitative, the new Baroque emphasis on music as expressive of emotions, especially tragic emotions such as sorrow on the death of a loved one, is very clear.

Video 7.1: “Tu Se Morta” (“You are dead”) from Orfeo

Listening Guide

- Composer: Claudio Monteverdi

- Composition: “Tu Se Morta” from Orfeo

- Date: 1607

- Genre: Recitative followed by a short chorus

- Form: Through-composed

- Nature of text: Lyrics in Italian

- Performing forces: Solo vocalist and basso continuo (here organ and theorbo), followed by chorus accompanied by a small orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is from one of the first operas.

- It is homophonic, accompanied by basso continuo.

- It uses word painting to emphasize Orfeo’s sorrow.

- Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct, and the range is about an octave in range.

- Most of its chords are minor and there are some dissonances.

- Its notated rhythms follow the rhythms of the text and are sung flexibly within a basic duple meter.

- It is sung in Italian like much Baroque opera.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Solo vocalist and basso continuo in homophonic texture; singer registers sadness and surprise through pauses and repetition of words such as “never to return” | “Tu se morta, se morta mia vita, e io respiro” And I breathe, you have left me. / “se’ da me par- tita per mai piu,” / You have left me forevermore, / “mai piu’ non tornare,” Never to return, |

| 0:52 | “No, No” (declaration to rescue Eurydice) intensified by being sung to high notes; melody descends to its lowest pitch on the word “abyss” | “ed io rimango-” and I remain- / “no, no, che se i versi alcuna cosa ponno,” No, no, if my verses have any power, / “n’andra sicuro a’ piu profondi abissi,” I will go confidently to the deepest abysses, |

| 1:11 | Descending pitches accompanied by dissonant chords when referring to the king of the shadows; melody ascends to high pitch for the word “stars” | “e, intenerito il cor del re de l’ombre,” And, having melted the heart of the king of shadows, / “meco trarotti a riverder le stelle,” Will bring you back to me to see the stars again, |

| 1:30 | Melody descends for the word “death” | “o se cia negherammi empio destino,” Or, if pitiless fate denies me this, / “rimarro teco in compagnia di morta.” I will remain with you in the company of death. |

| 1:53 | “Earth,” “sky,” and “sun” are set on ever higher pitches suggesting their experienced position from a human perspective | “Addio terra, addio cielo, e sole, addio;” Farewell earth, farewell sky, and sun, farewell. |

| 2:28 | Chorus & small orchestra responds; mostly homophonic texture with some polyphony; dissonance on the word “cruel.” | Oh cruel destiny, oh despicable stars, oh inexorable skies |

Lyrics:

Tu se’ morta, se morta, mia vita

ed io respiro, tu se’ da me partita,

se’ da me partita per mai piu,

mai piu’ non tornare, ed io rimango-

no, no, che se i versi alcuna cosa ponno,

n’andra sicuro a’ piu profondi abissi,

e, intenerito il cor del re de l’ombre,

meco trarotti a riverder le stelle,

o se cia negherammi empio destino,

rimarro teco in compagnia di morta.

Addio terra, addio cielo, e sole, addio

Translation:

You are dead, my darling, and I breathe?

You have departed from me

never to return, and I remain?

No, that if my verses can do but one thing

I will go confidently to the deepest abysses,

and having softened the heart of the king of shadows,

I will bring you back with me to see the stars again.

Or if impious fate were to deny me this

I will remain with you in the company of death,

farewell, earth; farewell, sky; and sun, farewell.

New Music for Instruments

The Baroque period saw an explosion in music written for instruments. Had you lived in the Middle Ages or Renaissance, you would have likely heard instrumental music, but much of it would have been either dance music or vocal music played by instruments. Around 1600, composers started writing more music specifically for musical instruments that might be played at a variety of occasions. One of the first composers to write for brass instruments was Giovanni Gabrieli (1554-1612). His compositions were played by ensembles having trumpets and sackbuts (the trombones of their day) as well as violins and an instrument called the cornet (which was something like a recorder with a brass mouthpiece). The early brass instruments, such as the trumpet and sackbut, as well as the early French horn, did not have any valves and were extremely difficult to play. Extreme mastery of the air column and embouchure (musculature around the mouth used to buzz the lips) were required to control the pitch of the instruments. Good Baroque trumpeters were highly sought after and in short supply. Often they were considered the aristocrats in the orchestra. Even in the wartime skirmishes of the Baroque era, trumpeters were treated as officers and given officer status when they became prisoners of war. Composers such as Bach, Vivaldi, Handel, and others selectively and carefully chose their desired instrumentation in order to achieve the exact tone colors, blend, and effects for each piece.

Giovanni Gabrieli was an innovative composer of the late Renaissance Venetian School. His masterful compositional technique carried over and established technique utilized during the Baroque era. Giovanni succeeded Andrea Gabrieli, his uncle, at Venice’s St. Mark’s Basilica as the organist following his uncle’s death in 1586. Giovanni held the position until his death in 1612. Giovanni’s works represent the peak of musical achievement for Venetian music.

Gabrieli continued and perfected the masterful traditional compositional technique known as cori spezzati (literally, “split choirs”). This technique was developed in the sixteenth century at St. Mark’s, where composers would contrast different instrumentalists and groups of singers utilizing the effects of space in the performance venue—that is, the church. Different sub-ensembles would be placed in different areas of the sanctuary. One sub-ensemble would play the “call,” and another would give the “response.” This musical back-and-forth is called antiphonal performance and creates a stereophonic sound between the two ensembles. Indeed, this placement of performers and the specific writing of the parts created the first type of stereo sound and three-dimensional listening experiences for parishioners in the congregation. Many of Gabrieli’s works were written for double choirs and double brass ensembles to perform simultaneously. See the interior of St. Mark’s Basilica with chambers or pergolo balconies on the left and right in Figure 7.5 below.

An example of one such piece with an eight-part setting is Gabrieli’s Jubilate. In later years, Giovanni became known as a famous music teacher. His most recognized student was Heinrich Schütz of Germany.

Focus Composition: Gabrieli, “Sonata pian’e forte” from Sacrae Symphoniae (1597)

Another famous composition by Gabrieli in eight parts, consisting of two four-part groups, is the Sonata pian’e forte, which is included in the Sacrea Symphoniae composed in 1597. This collection includes several instrumental canzoni for six- to eight-part ensembles. These, in addition to several Toccatas and Ricercars, have provided a great deal of interesting repertoires for brass players. Many of the original works by Gabrieli were written for sackbuts (early versions of the modern trombone) and cornetti (cupped-shape mouthpieces on a curved wooden instrument) but have since been transcribed for various brass ensembles.

Let’s listen to and study the Sonata pian’e forte from Gabrieli’s Sacrea Symphoniae. This collection is pioneering in musical scoring in that Gabrieli wrote specific louds and softs (volume) into the individual parts for the performers to observe. Through the use of its two keyboards played simultaneously, the pian’e forte could achieve two relative dynamic (volume) levels, soft and loud. The introduction of writing dynamics (volume p-soft to f-loud) into music by composers is a major step toward notating expression into the music score. Gabrieli also incorporated imitative polyphony and the use of polychoral techniques.

Video 7.2: Sonata pian’e forte—Giovanni Gabrieli

Listening Guide

As performed on instruments from the Renaissance/Baroque transition era, directed by Bernard Fabre-Garrus at the Festival des Cathedrales in Picardie (timings below correspond to this version).

- Composer: Giovanni Gabrieli

- Composition: Sonata pian e forte for 8 parts, C. 176 from Sacrea Symphonia

- Date: 1597

- Genre: Sonata

- Form: Through-composed in sections

- Nature of text: Antiphonal instrumental work in eight parts

- Performing forces: Two “choirs” (double instrumental quartet—8 parts) of traditional instruments—sackbuts (early trombones) and wooden cornets

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- antiphonal call and response;

- the use of musical dynamics (louds and softs written in the individual parts);

- and contrapuntal imitation

- Other things to listen for:

- Listen to the noted balance so the melody is heard throughout and how the instruments sound very “vocal” as from earlier time periods (the Renaissance).

- The piece’s texture is the division of the forces into two alternating groups in polychoral style.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Choir 1 introduces the first theme in a piano dynamic in a slow tempo and duple meter. Like many early sonatas and canzonas, the composition starts with a repeated-note motive. The notes and harmonies come from the Dorian mode, a predecessor to the minor scale. The composition starts in the key of G. | Strophe 1: Ave, generosa, “Hail generous one” |

| 0:29 | As the first choir cadences, the second choir begins, playing a new theme still at a piano dynamic and slow tempo. Later in the theme the repeated note motive (first heard in the first theme of the composition) returns. | Strophe 1 continues: Glorio- sa et intacta puella… “Noble, glorious, and whole woman…” |

| 0:52 | Choirs 1 and 2 play together in a tutti section at a forte dynamic. The new theme features faster notes than the first two themes. The key moves to the Mixolydian mode, a predecessor to the major scale, and the key moves to C. | Strophe 2: Nam hec superna infusio in te fuit… “The essences of heaven flooded into you…” |

| 1:02 | Central antiphonal section. Choir 1 opens with a short phrase using a piano dynamics and answered by choir 2 with a different short phrase, also with a piano dynamics. This call and response continues. Sometimes, the phrases last for only two measures; other times they are as long as four measures. After each passage of antiphonal exchanges, there is music of three to four measures in length where the whole ensemble joins together, usually with different melodic material (e.g., 40-43). The tonal or key center shifts during this section. There is a new theme that uses dotted rhythms that starts in measure 60 (approximately 2:07 in the recording). |

Strophe 3: O pulsherrima et dulcissima… “O lovely and tender one…” |

| 2:34 | Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues). | Strophe 4: Venter enim tuus gaudium havuit… “Your womb held joy…” |

Rise of the Orchestra and the Concerto

The Baroque period also saw the birth of the orchestra, which was initially used to accompany court spectacle and opera. In addition to providing accompaniment to the singers, the orchestra provided instrumental-only selections during such events. These selections came to include the overture at the beginning, the interludes between scenes and during scenery changes, and accompaniments for dance sequences. Other predecessors of the orchestra included the string bands employed by absolute monarchs in France and England and the town collegium musicum of some German municipalities. By the end of the Baroque period, composers were writing compositions that might be played by orchestras in concerts, such as concertos and orchestral suites.

The makeup of the Baroque orchestra varied in number and quality much more than the orchestra has varied since the nineteenth century; in general, it was a smaller ensemble than the later orchestra. At its core was the violin family, with woodwind instruments such as the flute, recorder, and oboe, and brass instruments, such as the trumpet or horn, and the timpani for percussion filling out the texture. The Baroque orchestra was almost always accompanied by harpsichord, which, together with one or more of the cellos or a bassoonist, provided a basso continuo.

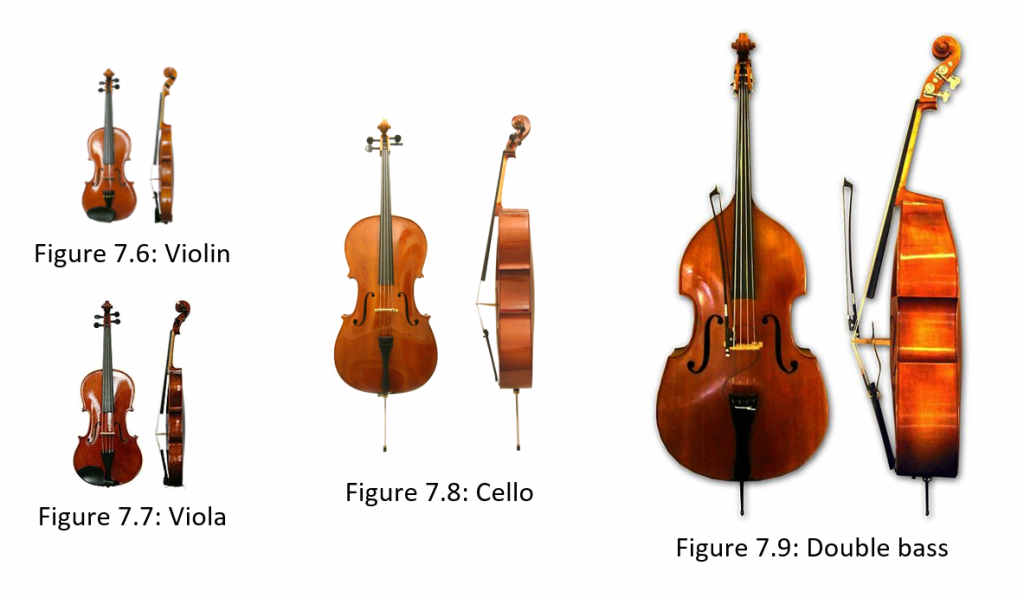

The new instruments of the violin family provided the backbone for the Baroque orchestra. The violin family—the violin, viola, cello (long form violoncello), and bass violin (or double bass)—were not the first bowed string instruments in Western classical music.

Figure 7.6: Violin | Author: Arbaras Gergeners | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: Public Domain

Figure 7.7: Viola | Author: Just plain Bill | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: Public Domain

Figure 7.8: Cello | Author: George Feitscher | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: CC BY 3.0

Figure 7.9: Double bass | Author: Andrew Kepert | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

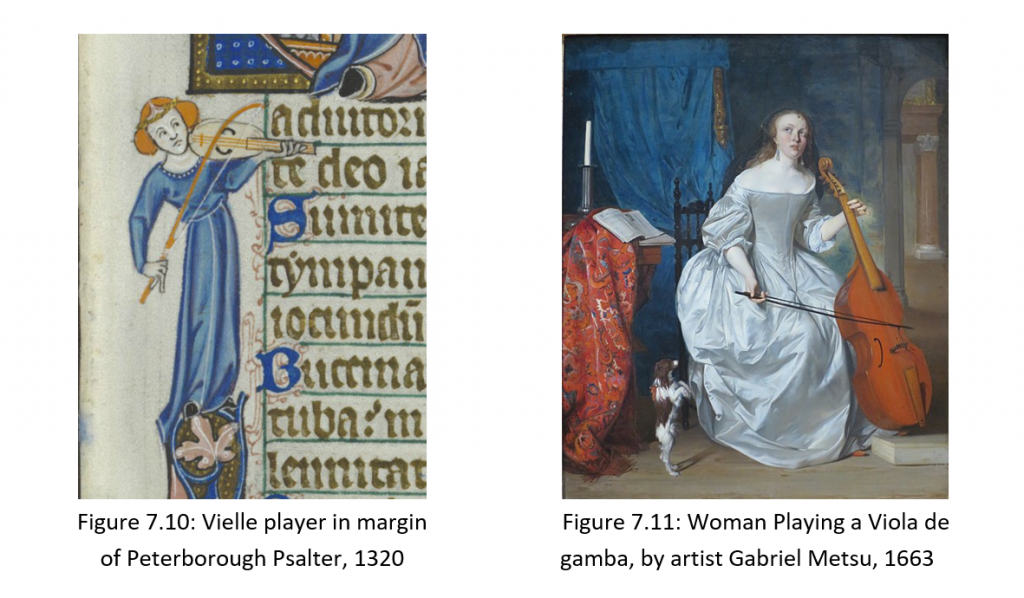

The Middle Ages had its fiddle (or vielle; see Figure 7.10), and the Renaissance had the viola da gamba (see Figure 7.11).

Figure 7.10: Vielle player in margin of Peterborough Psalter, ca. 1320 | Artist: Unknown | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: Public Domain

Figure 7.11: Woman Playing a Viola de gamba, 1663 | Artist: Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667) | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: Public Domain

Bowed strings attained a new prominence in the seventeenth century with the widespread and increased manufacturing of violins, violas, cellos, and basses. Some of these instruments, such as those made by Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737), are still sought after today as some of the finest specimens of instruments ever made.

With the popularity of the violin family, instruments of the viola da gamba family fell to the sidelines. Composers started writing compositions specifically for the members of the violin family, often arranged with two groups of violins, one group of violas, and a group of cellos and double basses, who sometimes played the same bass line as played by the harpsichord. One of the first important forms of this instrumental music was the concerto. The word concerto comes from the Latin and Italian root concertare, which has connotations of both competition and cooperation. The musical concerto might be thought to reflect both meanings. A concerto is a composition for an instrumental soloist or soloists and orchestra; in a sense, it brings together these two forces in concert; in another sense, these two forces compete for the attention of the audience. A concerto grosso is a composition for a solo group (known as the concertino) and full orchestra (the ripieno) . A concerto is an orchestral form that exploits the idea of pitting soft sounds against loud ones. Concertos are most often in three movements that follow a tempo pattern of fast–slow–fast. Most first movements of concertos are in what has come to be called ritornello form. As its name suggests, a ritornello is a repeated musical theme used in a concerto grosso. It is a returning to the theme or refrain played by the full orchestral ensemble. In a concerto, the ritornello alternates with the solo sections that are played by the soloist or soloists.

Some of the most famous of these concertos were the Brandenburg Concertos written by Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach wrote six works which he dedicated the Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg. Three of these works follow the concerto grosso style.

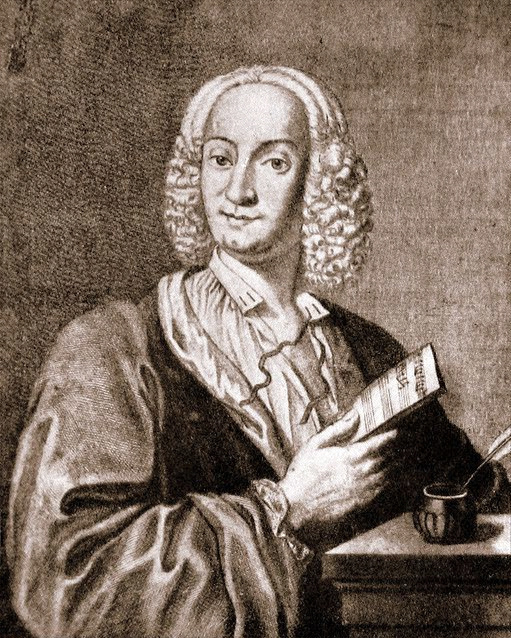

Music of Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

One of the most prolific and important composers of the Baroque solo concerto was the Italian Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741). His father taught him to play at a young age, and he probably began lessons in music composition as a young teen.

Vivaldi began studying for the priesthood at age fifteen and, once ordained at age twenty-five, received the nickname of “The Red Priest” because of his hair color. He worked in a variety of locations around Europe, including at a prominent Venetian orphanage called the Ospedale della Pietà. There he taught music to girls, some of whom were illegitimate daughters of prominent noblemen and church officials from Venice. This orphanage became famous for the quality of music performed by its inhabitants. Northern Europeans, who would travel to Italy during the winter months on what they called “The Italian Tour” —to avoid the cold and rainy weather of cities such as Paris, Berlin, and London—wrote home about the fine performances put on by these orphans in Sunday afternoon concerts.

These girls performed concertos such as Vivaldi’s well-known Four Seasons. The Four Seasons refers to a set of four concertos, each of which is named after one of the seasons. As such, it is an example of program music, a type of music that would become more prominent in the Baroque period. Program music is Instrumental descriptive music that is associated with a nonmusical idea. It is instrumental music that represents something extra musical, such as the words of a poem or narrative or the sense of a painting or idea. A composer might ask orchestral instruments to imitate the sounds of natural phenomena, such as a babbling brook or the cries of birds. Most program music carries a descriptive title that suggests what an audience member might listen for. In the case of the Four Seasons, Vivaldi connected each concerto to an Italian sonnet—that is, to a poem that was descriptive of the season to which the concerto referred. Thus, in the case of Spring, the first concerto of the series, you can listen for the “festive song” of birds, “murmuring streams,” “breezes,” and “lightning and thunder.”

Focus Composition: Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons

Each of the concertos in the Four Seasons has three movements, organized in a fast–slow–fast succession. We’ll listen to the first fast movement of Spring. Its “Allegro” subtitle is an Italian tempo marking that indicates music that is fast. As a first movement, it is in ritornello form. The movement opens with the ritornello, in which the orchestra presents the opening theme. This theme consists of motives, small groupings of notes and rhythms that are often repeated in sequence. This ritornello might be thought to reflect the opening line from the sonnet. After the ritornello, the soloist plays with the accompaniment of only a few instruments—that is, the basso continuo. The soloist’s music uses some of the same motives found in the ritornello but plays them in a more virtuosic way, showing off one might say.

As you listen, try to hear the alternation of the ritornellos and solo sections. Listen also for the motor rhythm, the constant subdivision of the steady beat, and the melodic themes that unfold through melodic sequences. Do you hear birds, a brook, and a thunderstorm? Do you think you would have associated these musical moments with springtime if, instead of being called the Spring Concerto, the piece was simply called Concerto No. 1?

Video 7.3: A. Vivaldi: “La Primavera” (Spring)—Concerto for violin, strings, and basso continuo in E major

Listening Guide

Performed by: Giuliano Carmignola (solo violin); Giorgio Fava (violin I); Gino Mangiocavallo (violin II); Enrico Parizzi (viola); Walter Vestidello (violoncello); Alberto Rasi (violone); Giancarlo Rado (archlute); Andrea Marcon (harpsichord); I Sonatori

de la Gioiosa Marca / Giuliano Carmignola (conductor).

- Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

- Composition: The first movement of “Spring” from The Four Seasons

- Date: 1720s

- Genre: Solo concerto and program music

- Nature of text: The concerto is accompanied by an Italian sonnet about springtime. The first five lines are associated with the first movement:

Springtime is upon us.

The birds celebrate her return with festive song,

and murmuring streams are softly caressed by the breezes.

Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark mantle over heaven,

Then they die away to silence, and the birds take up their charming songs once more. - Performing forces: Solo violinist and string orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is the first movement of a solo concerto that uses ritornello form.

- This is program music.

- It uses terraced dynamics.

- It uses a fast allegro tempo.

- Other things to listen for:

- The orchestral ritornellos alternate with the sections for solo violin

- Virtuoso solo violin lines

- Motor rhythm

- Melodic themes composed of motives that spin out in sequences

| Time | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:08 | Ritornello (Springtime is upon us.) Full string orchestra. Note the contrast of dynamics between loud and soft. |

| 0:36 | Solo (The birds celebrate Spring’s return with festive song,) |

| 1:07 | Ritornello |

| 1:14 | Solo (and murmuring streams are softly caressed by the breezes.) |

| 1:35 | Ritornello |

| 1:42 | Solo (Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark mantle over heaven,) Note how Vivaldi portrays thunder AND lightning! |

| 2:07 | Ritornello (in a minor key—they got wet in the storm!) |

| 2:15 | Solo (Then they die away to silence, and the birds take up their charming songs once more.) |

| 2:32 | Ritornello? Unexplained—what is this new music doing here? (This passage is often played much faster and brighter…) |

| 2:45 | Solo (more birds…) |

| 2:58 | Ritornello |

For more about Vivaldi, watch Video 7.4: Rick Wakeman on Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (2015)—(optional)

Something to Think About

Most program music carries a descriptive title that suggests what an audience member might listen for. In the case of the Four Seasons, Vivaldi connected each concerto to an Italian sonnet—that is, to a poem that was descriptive of the season to which the concerto referred. Thus, in the case of Spring, the first concerto of the series, you can listen for the “festive song” of birds, “murmuring streams,” “breezes,” and “lightning and thunder.”

What popular songs today may contain program music, even containing a descriptive title?

Music of George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

George Frideric Handel was one of the superstars of the late Baroque period. He was born the same year as one of our other Baroque superstars, Johann Sebastian Bach, not more than 150 miles away in Halle, Germany. His father was an attorney and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Handel decided that he wanted to be a musician instead. With the help of a local nobleman, he persuaded his father to agree. After learning the basics of composition, Handel journeyed to Italy to learn to write opera. Italy, after all, was the home of opera, and opera was the most popular musical entertainment of the day. After writing a few operas, he took a job in London, England, where Italian opera was very much the rage, eventually establishing his own opera company and producing scores of Italian operas, which were initially very well received by the English public. After a decade or so, however, Italian opera in England imploded. Several opera companies there each competed for the public’s business. The divas who sang the main roles and whom the public bought their tickets to see demanded high salaries. In 1728, a librettist named John Gay and a composer named Johann Pepusch premiered a new sort of opera in London called a ballad opera. It was sung entirely in English, and its music was based on folk tunes known by most inhabitants of the British Isles. For the English public, the majority of whom had been attending Italian opera without understanding the language in which it was sung, English-language opera was a big hit. Both Handel’s opera company and his competitors fought for financial stability, and Handel had to find other ways to make a profit. He hit on the idea of writing English oratorio.

The Oratorio is a dramatic work for soloists, chorus and orchestra. It is a sung drama or sacred opera based on stories from the Bible with no staging or costumes. . Like operas, they are relatively long works, often spanning over two hours when performed in entirety. Like opera, oratorios are entirely sung to orchestral accompaniment. They feature recitatives, arias, and choruses, just like opera. Most oratorios also tell the story of an important character from the Christian Bible. But oratorios are not acted out. Historically speaking, this is the reason that they exist. During the Baroque period at sacred times in the Christian church year such as Lent, stage entertainment was prohibited. The idea was that during Lent, individuals should be looking inward and preparing themselves for Easter, and attending plays and operas would distract from that. Nevertheless, individuals still wanted entertainment, hence, oratorios. These oratorios would be performed as concerts (not in the church), but because they were not acted out, they were perceived as not having a “detrimental” effect on the spiritual lives of those in the audience. The first oratorios were performed in Italy; then they spread elsewhere on the continent and to England.

Handel realized how powerful ballad opera, sung in English, had been for the general population and started writing oratorios, but in the English language. He used the same music styles as he had in his operas, only including more choruses. In no time at all, his oratorios were being lauded as some of the most popular performances in London.

Handel’s most famous oratorio is entitled Messiah and was first performed in 1741. About the life of Christ, it was written for a benefit concert to be held in Dublin, Ireland. Atypically, his librettist took the words for the oratorio straight from the King James Version of the Bible instead of putting the story into his own words. Once in Ireland, Handel assembled solo singers as well as a chorus of musical amateurs to sing the many choruses he wrote for the oratorio. There it was popular, if not controversial. One of the soloists was a woman who was a famous actress. Some critics remarked that it was inappropriate for a woman who normally performed on the stage to be singing words from sacred scripture. Others objected to sacred scripture being sung in a concert instead of in church. Perhaps influenced by these opinions, Messiah was performed only a few times during the 1740s. But when it was first performed for King George in London, he was so moved by the performance that he stood for the finale of the Messiah, the Hallelujah Chorus as a sign of respect to Handel’s music. Since the end of the eighteenth century, however, it has been performed more than almost any other composition of classical music. While these issues may not seem controversial to us today, they remind us that people still disagree about how sacred texts should be used and about what sort of music should be used to set them.

Focus Composition: Handel’s Messiah

We’ve included three numbers from Handel’s Messiah as part of our discussion of this focus composition. We’ll first listen to a recitative entitled “Comfort Ye” that is directly followed by an aria entitled “Every Valley.” These two numbers are the second and third numbers in the oratorio. Then we’ll listen to the Hallelujah Chorus, the most famous number from the composition that falls at the end of the second of the three parts of the oratorio.

Video 7.5: “Comfort ye my people / Every Valley” performed by Anthony Rolfe Johnson (tenor), with the Monteverdi Choir, John Elliot Gardiner, conductor

Listening Guide

- Composer: George Frideric Handel

- Composition: “Comfort Ye” and “Every Valley” from Messiah

- Date: 1741

- Genre: Accompanied recitative and aria from an oratorio

- Form: Accompanied recitative—through composed; aria—binary form AA’

- Nature of text: English-language libretto quoting the Bible

- Performing forces: Solo tenor and orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- As an oratorio, it uses the same styles and forms as operas but is not staged.

- The aria is very virtuoso with its melismas and alternates between orchestral ritornellos and solo sections.

- Other things to listen for:

- The accompanied recitative uses more instruments than standard basso continuo-accompanied recitative, but the vocal line retains the flexibility of recitative.

- Motor rhythm in the aria

- In a major key

- In the aria, the second solo section is more ornamented than the first, as was often the custom.

Accompanied Recitative: “Comfort Ye” and Aria: “Every Valley” (beginning at 2:22)

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Reduced orchestra playing piano (softly) repeated notes | |

| 0:13 | Mostly step-wise, conjunct sung melody; homophonic texture |

Vocalist and light orchestral accompaniment: “Comfort Ye my people” |

| 0:27 | Orchestra and vocalist alternate phrases until the recitative ends | Vocalist and light orchestral accompaniment: Comfort ye my people says your God; speak ye comforter of Jerusalem; and cry upon….that her iniquity is pardoned. A voice of him that cry-eth in the wilderness. Prepare ye the way for the Lord. Make straight in the desert a highway for our God |

| 2:22 | Repeated motives; starts loud, ends with an echo | Orchestra plays ritornello |

| 2:39 | Soloist presents melodic phrase first heard in the ritornello and the orchestra echoes this phrase | Tenor and orchestra: Every valley shall be exalted |

| 2:52 | Long melisma on the word exalted…repeats High note on mountain and low note on “low” |

Tenor and orchestra: Shall be exalted

And every mountain and hill made low |

Video 7.6: Hallelujah Chorus, performed by English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

Listening Guide

- Composer: George Frideric Handel

- Composition: “Hallelujah” from Messiah

- Date: 1741

- Genre: Chorus from an oratorio

- Form: Sectional; sections delineated by texture changes

- Nature of text: English-language libretto quoting the Bible

- Performing forces: Solo tenor and orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is for four-part chorus and orchestra.

- It uses a sectional form where sections are delineated by changes in texture.

- Other things to listen for:

- In a major key, using mostly major chords

- Key motives repeat over and over, often in sequence

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Orchestra: Introduces main musical motive in a major key with a homophonic texture where parts of the orchestra play the melody and other voices provide the accompaniment |

|

| 0:09 | Chorus with orchestra: Here the choir and the orchestra provide the melody and accompaniment of the homophonic texture |

Hallelujah |

| 0:26 | Chorus with orchestra: Dramatic shift to monophonic with the voices and orchestra performing the same melodic line at the same time |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

| 0:34 | Chorus with orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before | Hallelujah |

| 0:38 | Chorus with orchestra: Monophonic texture, as before | For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

| 0:45 | Chorus with orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before | Hallelujah |

| 0:49 | Chorus with orchestra: Texture shifts to non-imitative polyphonic with the initial entrance of the sopranos, then the tenors, then the altos |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

| 1:17 | Chorus with orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before | The Kingdom of this world is begun |

| 1:36 | Chorus with orchestra: Imitative polyphony starts in basses, then is passed to tenors, then to the altos, and then to the sopranos |

And he shall reign for ever and ever |

| 1:57 | Chorus with orchestra: Monophonic texture, as before | King of Kings |

| 2:01 | Chorus with orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before | Forever, and ever hallelujah hallelujah |

| 2:05 | Chorus with orchestra: Each entrance is sequenced higher; the women sing the monophonic repeated melody motive Monophony alternating with homophony |

And Lord of Lords…Repeated alternation of the monophonic king of kings and lord of lords with homophonic for ever and ever |

| 2:36 | Chorus with orchestra: Homophonic texture | King of kings and lord of lords |

| 2:40 | Chorus with orchestra: Polyphonic texture (with some imitation) | And he shall reign for ever and ever |

| 2:52 | Chorus with orchestra: The alternation of monophonic and homophonic textures | King of kings and lord of lords alternating with “for ever and ever” |

| 3:01 | Chorus with orchestra: Mostly homophonic | And he shall reign…Hallelujah |

Focus Composition: Movements from Handel’s Water Music Suite

Although Handel is perhaps best known today for his operas and oratorios, he also wrote a lot of instrumental music, from concertos like Vivaldi wrote to a kind of music called the suite. Suites were compositions having many contrasting movements. The idea was to provide diverse music in one composition that might be interesting for playing and listening. They could be written for solo instruments such as the harpsichord or for orchestral forces, in which case we call them orchestral suites. They often began with movements called overtures and were modeled after the overtures played before operas. Then they typically consisted of stylized dance movements. By stylized dance, we mean a piece of music that sounds like a dance but that was not designed for dancing. In other words, a stylized dance uses the distinct characteristics of a dance and would be recognized as sounding like that dance but might be too long or too complicated to be danced to.

Dancing was very popular in the Baroque period, as it had been in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. We have several dancing textbooks from the Baroque period that mapped out the choreography for each dance. Some of the most popular dances included the saraband, gigue, minuet, and bourrée. The saraband was a slow dance in triple meter, whereas the gigue (or jig) was a very fast dance with triple subdivisions of the beats. The minuet was also in triple time but danced at a much more stately tempo. The bourrée, on the other hand, was danced at a much faster tempo, and always in duple meter.

When King George I asked Handel to compose music for an evening’s diversion, the suite was the genre to which Handel turned. This composition was for an event that started at 8 p.m. on Wednesday the seventeenth of July 1717. King George I and his noble guests would launch a barge ride up the Thames River to Chelsea. After disembarking and spending some time on shore, they re-boarded at 11 p.m. and returned via the river to Whitehall Palace, from whence they came. A contemporary newspaper remarked that the king and his guests occupied one barge while another held about fifty musicians and reported that the king liked the music so much that he asked it to be repeated three times. Hence, Handel wrote the Water Music Suite, for King George I in 1717 to entertain his guests as they rode on a barge up and down the Thames River to Chelsea.

Many of the movements that were played for the occasion were written down and eventually published as three suites of music, each in a different key. You have two stylized dance movements from one of these suites here, a bourrée and a minuet. We do not know with any certainty in what order these movements were played or even exactly who played them on that evening in 1717, but when the music was published in the late eighteenth century, it was set for two trumpets, two horns, two oboes, first violins, second violins, violas, and a basso continuo, which included a bassoon, cello(s), and harpsichord.

The bourrée, as noted above, is fast and in duple time. The minuet is in a triple meter and taken at a more moderate tempo. They use repeated strains or sections of melodies based on repeated motives. As written in the score, as well as interpreted today in the referenced recording, different sections of the orchestra—the strings, woodwinds, and sometimes brass instruments—each get a time to shine, providing diverse timbres and thus musical interest. Both are good examples of binary form.

Video 7.7: Handel’s Water Music Suite No. 1 in F Major VII Bourrée

Video 7.8: Handel: Water Music Suite No. 1 in F Major, VI. Menuet

Music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

During the seventeenth century, many families passed their trades down to the next generation so that future generations could continue to succeed in a vocation. This practice also held true for Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach was born into one of the largest musical families in Eisenach of the central German region known as Thuringia. He was orphaned at the young age of ten and raised by an older brother in Ohrdruf, Germany. Bach’s older brother was a church organist who prepared the young Johann for the family vocation. The Bach family, though great in number, were mostly of the lower musical stature of town’s musicians and/or Lutheran Church organist. Only a few of the Bachs had achieved the accomplished stature of court musicians, but the Bach family members were known and respected in the region. Bach also, in turn, taught four of his sons, who later became leading composers for the next generation.

Bach received his first professional position at the age of eighteen in Arnstadt, Germany, as a church organist. Bach’s first appointment was not a good philosophical match for the young aspiring musician. He felt his musical creativity and growth were being hindered and his innovation and originality unappreciated. The congregation seemed sometimes confused and felt the melody was lost in Bach’s writings. He met and married his first wife while in Arnstadt, marrying Maria Barbara (possibly his cousin) in 1707. They had seven children together; two of their sons, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Phillipp Emmanuel, as noted above, became major composers for the next generation. Bach later was offered and accepted another position in Műhlhausen.

He continued to be offered positions that he accepted and so advanced in his professional position/title up to a court position in Weimer, where he served nine years from 1708 to 1717. This position had a great number of responsibilities. Bach was required to write church music for the ducal church (the church for the duke that hired Bach), to perform as church organist, and to write organ music and sacred choral pieces for choir, in addition to writing sonatas and concertos (instrumental music) for court performance for his duke’s events. While at this post, Bach’s fame as an organist and the popularity of his organ works grew significantly.

Bach soon wanted to leave for another offered court musician position, and his request to be released was not received well. This difficulty attests to the work relations of court musicians and their employers. Dukes expected and demanded loyalty from their court musician employees. Because musicians were looked upon somewhat as court property, the duke of the court often felt betrayed when a court musician wanted to leave. Upon hearing of Bach’s desire to leave and work for another court for the prince of Cöthen, the duke at Weimer refused to accept Bach’s resignation and threw Bach into jail for almost a month for submitting his dismissal request before relenting and letting Bach go to the Cöthen court.

The prince at Cöthen was very interested in instrumental music. The prince was a developing amateur musician who did not appreciate the elaborate church music of Bach’s past; instead, the prince desired instrumental court music, so Bach focused on composing instrumental music. In his five year (1717-1723) tenure at Cöthen, Bach produced an abundance of clavier music, six concerti grossi honoring the Margrave of Brandenburg, suites, concertos, and sonatas. While at Cöthen (1720), Bach’s first wife, Maria Barbara, died. He later married a young singer, Anna Magdalena, and they had thirteen children together. Half of these children did not survive infancy. Two of Bach’s sons birthed by Anna, Johann Christoph and Johann Christian, also went on to become two of the next generation’s foremost composers.

At the age of thirty-eight, Bach assumed the position as cantor of the St. Thomas Lutheran Church in Leipzig, Germany. Several other candidates were considered for the Leipzig post, including the famous composer Telemann, who refused the offer. Some on the town council felt that since the most qualified candidates did not accept the offer, the less talented applicant would have to be hired. It was in this negative working atmosphere that Leipzig hired its greatest cantor and musician. Bach worked in Leipzig for twenty-seven years (1723-1750).

Leipzig served as a hub of Lutheran church music for Germany. Not only did Bach have to compose and perform; he also had to administer and organize music for all the churches in Leipzig. He was required to teach in choir school in addition to all of his other responsibilities. Bach composed, copied needed parts, directed, rehearsed, and performed a cantata on a near weekly basis. Cantatas are major church choir works that involve soloist, choir, and orchestra. Cantatas have several movements and last for fifteen to thirty minutes. Cantatas are still performed today by church choirs, mostly on special occasions such as Easter, Christmas, and other festive church events.

Bach felt that the rigors of his Leipzig position were too bureaucratic and restrictive due to town and church politics. Neither the town nor the church really ever appreciated Bach. The church and town council refused to pay Bach for all the extra demands/responsibilities of his position and thought basically that they would merely tolerate their irate cantor, even though Bach was the best organist in Germany. Several of Bach’s contemporary church musicians felt his music was not according to style and types considered current, a feeling that may have resulted from professional jealousy. One contemporary critic felt Bach was “old Fashioned.” Beyond this professional life, Bach had a personal life centered on his large family.

He wrote a little homeschool music curriculum entitled The Notebook of Anna Magdalena Bach. At home, the children were taught the fundamentals of music, music copying, performance skills, and other musical content. Bach’s children utilized their learned music copying skills in writing the parts from the required weekly cantatas that Sebastian was required to compose. Bach’s deep spirituality is evident and felt in the meticulous attention to detail of his sacred works, such as his cantatas. Indeed, the spirituality of Bach’s Passions and his Mass are unequaled by other composers.

Bach did not travel much, with the exception of being hired as a consultant with construction contracts to install organs in churches. He would be asked to test the organs and to be part of their inauguration ceremony and festivities. The fee for such a service ranged from a cord of wood to possibly a barrel of wine. In 1747, Bach went on one of these professional expeditions to the Court of Frederick the Great in Potsdam, an expedition that proved most memorable. Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, served as the accompanist for the monarch of the court, who played the flute. Upon Bach’s arrival, the monarch showed Bach a new collection of pianos—pianos were beginning to replace harpsichords in homes of society. With Bach’s permission, the king presented him with a theme/melody on which Bach based one of his incredible themes for the evening’s performance. Upon Bach’s return to Leipzig, he further developed the king’s theme, adding a trio sonata, and entitled it The Musical Offering, attesting to his highest respect for the monarch and stating that the king should be revered.

Bach later became blind but continued composing by dictating to his children. He had also already begun to organize his compositions into orderly sets of organ chorale preludes, preludes and fugues for harpsichord, and organ fugues. He started to outline and recapitulate his conclusive thoughts about Baroque music, forms, performance, composition, fugal techniques, and genres. This knowledge and innovation appears in such works as The Art of Fugue—a collection of fugues all utilizing the same subject left incomplete due to his death—the thirty-three Goldberg Variations for harpsichord, and the Mass in B minor.

Bach was an intrinsically motivated composer who composed music for himself and a small group of students and close friends. This type of composition was a break from the previous norms of composers. Even after his death, Bach’s music was ignored and not valued by the musical public. It was, however, appreciated and admired by great composers such as Mozart and Beethoven.

Over the course of his lifetime, Bach produced major works, including The Well-Tempered Clavier (forty-eight preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys), three sets of harpsichord suites (six movements in each set), the Goldberg Variations, many organ fugues and chorale preludes (chorale preludes are organ solos based upon church hymns—several by Luther), the Brandenburg Concertos, and composite works such as A Musical Offering and The Art of Fugue, an excess of 200 secular and sacred cantatas, two Passions from the gospels of St. Matthew and St. John, a Christmas Oratorio, a Mass in B minor, and several chorale/hymn harmonizations, concertos, and other orchestral suites and sonatas.

Focus Composition: Bach, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” Cantata, BWV 80

Bach’s “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” cantata, like most of his cantatas, has several movements. It opens with a polyphonic chorus that presents the first verse of the hymn. After several other movements (including recitatives, arias, and duets), the cantata closes with the final verse of the hymn arranged for four parts. For a comparison of cantatas, oratorios, and opera, please see the chart earlier in this chapter.

Bach composed some of this music when he was still in Weimar (BWV 80A) and then revised and expanded the cantata for performance in Leipzig around 1730 (BWV 80B), with additional reworkings between 1735 and 1740 (BWVA 80).

Cantata No. 80 “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” BWV 80: Opening Chorale

Listening Guide

- Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

- Composition: Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, translated to “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” from Bach Cantata 80 (BWV 80)

- Date: 1715-1740

- Genre: First-movement polyphonic chorus and final-movement chorale from a church cantata

- Form: Sectional, divided by statements of Luther’s original melody line in sustained notes in the trumpets, oboes, and cellos

- Nature of text: In German, written by Martin Luther in the late 1520s

- Performing forces: Choir and orchestra (vocal soloists appear elsewhere in the cantata). See this translation for the original German translated by Frederick H. Hedge.

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- This is representative of Bach’s mastery of taking a Martin Luther hymn and arranging it in imitative polyphony for all four voice parts and instrumental parts.

- Other things to listen for:

- Theme to the first verse or strophe of the hymn. He weaves these new melody lines into a beautiful polyphonic choral work.

- Most of the time the instruments double (or play the same music as) the four voice parts.

- He also has the trumpets, oboes, and cellos divide up Luther’s exact melody into nine phrases. They present the first phrase after the first section of the chorus and then subsequent phrases throughout the chorus. When they play the original melody, they do so in canon: the trumpets and oboes begin and then the cellos enter after about a measure.

- Also listen to see if you can hear the augmentation in the work. The original tune is performed in this order of the voices: Tenors, Sopranos, Tenors, Sopranos, Basses, Altos, Tenors, Sopranos, and then the Tenors.

Keyboard Instruments

Bach was born into a century that saw great advancements in keyboard instruments and keyboard music. The keyboard instruments included harpsichord, clavichord, and organ. The harpsichord is a keyboard instrument whose strings are put into motion by pressing a key that facilitates a plucking of a string by quills of feathers (instead of being struck by hammers like the piano). The tone produced on the harpsichord is bright but cannot be sustained without restriking the key. Dynamics are very limited on the harpsichord. In order for the tone to continue on the harpsichord, keys are replayed, trills are utilized, embellishments are added, and chords are broken into arpeggios.

During the early Baroque era, the clavichord remained the instrument of choice for the home; indeed, it is said that Bach preferred it to the harpsichord. It produced its tone by means of keys attached to metal blades that strike the strings. As we will see in the next chapter, by the end of the 1700s, the piano would replace the harpsichord and clavichord as the instrument of choice for residences.

Bach was best known as a virtuoso organist, and he had the opportunity to play on some of the most advanced pipe organs of his day. Sound is produced on the organ with the depression of one or more of the keys, which activates a mechanism that opens pipes of a certain length and pitch through which wind from a wind chest rushes. The length and material of the pipe determine the tones produced. Levers called stops provide further options for different timbres. The Baroque pipe organ operated on relatively low air pressure compared to today’s organs, resulting in a relatively thin transparent tone and volume.

Most Baroque organs had at least two keyboards, called manuals (after the Latin word for hand), and a pedal board played by the two feet. The presence of multiple key- boards and a pedal board made the organ an ideal instrument for polyphony. Each of the keyboards and the pedal board could be assigned different stops and thus could produce different timbres and even dynamic levels, which helped define voices of the polyphonic texture. Bach composed many of his chorale preludes and fugues for the organ.

Focus Composition: Bach, “Little” Fugue in G Minor (BWV 578)

The fugue is one of the most spectacular and magnificent achievements of the Baroque period. During this era of fine arts innovation, scientific research, natural laws, and systematic approaches to imitative polyphony were further developed and standardized. Polyphony first emerged in the late Middle Ages. Independent melodic lines overlapped and were woven. In the Renaissance, polyphony was further developed by a greater weaving of the independent melodic lines. The Baroque composers, under the influence of science, further organized it into a system—more on this later. The term fugue comes from the Latin word “fuga,” which means running away or to take flight. The fugue is a contrapuntal (polyphonic) piece for a set number of musicians, usually three of four. The musical theme or main melody of a fugue is called the subject.

You may think of a fugue as a gossip party. The subject (of gossip) is introduced in one corner of the room between two people. Another person in the room then begins repeating the gossip while the original conversation continues. Then another person picks up on the story and begins repeating the now third-hand news, and it then continues a fourth time. A new observer walking into the room will hear bits and pieces from four conversations at one time—each repeating the original subject (gossip). This is how a fugue works. When the subject has been stated in every voice part in the fugue, we call this the exposition. Most fugues are in the four standard voices: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. We will refer to the parts in these voices for both voices and instruments.

At the beginning of the fugue, any of the four voices can begin with the subject. Then another voice starts with the subject at a time dictated in the music while the first voice continues to more material. The imitation is continued through all the voices. The exposition of the fugue is over when all the voices complete the initial subject.

Voice 1 Soprano: Subject—continues in a countersubject

Voice 2 Alto: Subject—continues in a countersubject

Voice 3 Tenor: Subject—continues in a countersubject

Voice 4 Bass: Subject—continues in a countersubject

After the exposition is completed, it may be repeated in a different order of voices, or it may continue with less weighted entrances at varying lengths known as episodes. This variation provides a little relaxation or relief from the early regimented systematic polyphony of the exposition. In longer fugues, the episodes are followed by a section in another key with continued overlapping of the subject. This episode and modulation can continue to repeat until they return to the original key.