11 Music of the 20th and 21st Centuries

Learning Objectives

- Explain how progressive modern music sounds different from music of the “common practice era.”

- Identify the historical and ideological changes that caused the stylistic upheaval of modernism.

- Identify key stylistic attributes of twentieth-century modernist music.

- Compare and contrast the stylistic characteristics of different movements in twentieth- and twenty-first-century music, including impressionism, expressionism, primitivism, neoclassicism, minimalism, and post-minimalism.

- Explain ways that technology and media have influenced music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

- Identify important trends in twenty-first-century classical music.

Adapted from “Making Music Modern” from Sound Reasoning

by Anthony Brandt

Edited by Francis Scully

What makes music “modern”? This module proposes that heightened ambiguity differentiates experimental twentieth-century music from the classical repertoire.

Introduction

In this module, we will study the ways in which progressive modern music differs from classical music. We will then use the conceptual and listening tools that we have developed in earlier modules as an entryway into the modern repertoire.

The Shock of the New

A little over three hundred years ago, Sir Isaac Newton created the first mathematically coherent explanation of the universe. To Sir Isaac Newton, nature behaved like a well-regulated, predictable machine. Give Newton comprehensive information about the universe and he could have predicted the future. Famously inspired by a falling apple, Newton’s laws are confirmed by our direct perceptions and agree with our common sense. We still launch satellites into orbit using his method of calculation. But Newton’s view of a predictable universe turned out to be deeply flawed. Perhaps the most fundamental scientific discovery of the 20th century was the recognition that ambiguity is irrevocably built into nature.

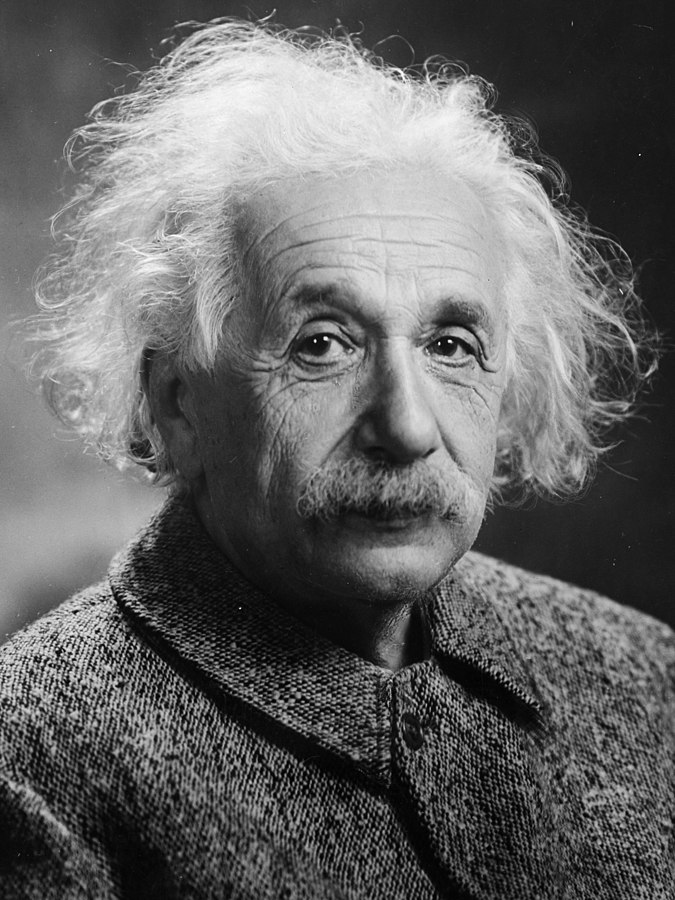

The Theory of Relativity

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity stipulates that the speed of light is constant for all observers. One startling consequence of this is that simultaneity and cause and effect are not absolute but relative to one’s perspective. It is possible for one observer to report two events as happening at the same time that another observer sees as happening in sequence. Thus, according to the Theory of Relativity, there is no definitive “reality,” no commanding perspective that overrides all others. Instead, nature allows for multiple, and even contradictory, points of view. Decades of experiments have confirmed Einstein’s theory.

Psychology

It is not just the outer world that is saturated with ambiguity. Sigmund Freud was the first scientist to deeply explore the concept of the unconscious—mental processes that lie beyond our direct awareness. These range from metabolic processes like breathing to the complex motivations that underlie everyday decisions. A century of research has established that most of human thinking is unconscious. Various experimental methods have been devised to explore the unconscious, from dream analysis to word association, Rorschach tests, brain scans, and more. Yet deciphering our unconscious thoughts remains elusive. Thus, not only must we accept the ambiguities of the natural world, we must acknowledge it within ourselves.

Nature’s Ambiguities and Daily Life

Nature’s ambiguities generally lie outside our direct perception. Relativistic effects only become pronounced near the speed of light. Unconscious thoughts, by definition, lie outside our immediate awareness. Thus, it is possible to be largely oblivious to the ambiguities inherent in nature. However, one hundred years of scientific research has established that ambiguity imbues the world around and within us.

Ambiguity in Art

As ambiguity became heightened in science, so too did ambiguity become heightened in art.

All great works of art leave questions open: Is Hamlet mad or just pretending to be? Is the Mona Lisa smiling? Twentieth-century artists didn’t need to make their art ambiguous—it already was. Instead, they strove to amplify art’s ambiguity. Painters created abstract images that did not refer explicitly to observable reality. Writers created non-linear narratives that shifted around in time or were told from multiple perspectives. How did composers heighten the ambiguity in music?

Heightening Musical Ambiguity

Because it is non-verbal and often non-representational, music is particularly ambiguous. And yet, as the following discussion will make clear, classical composers put a high value on clarity and resolution. Progressive twentieth-century composers shifted the balance much more strongly towards the uncertain and the unresolved.

Individualized Musical Languages

“U tita enska aka ca vik i totar i tari”

Speaking in a personal language—no matter how thoroughly imagined and consistent—automatically heightens ambiguity. The sentence above—an example of Skerre, a language invented by linguist Doug Ball—would take a long time and a great deal of analysis to decipher. Language functions most conveniently in a community where everyone shares a similar vocabulary and syntax. Because music does not have fixed definitions, linguistic parallels are often misleading. Nevertheless, the shared materials and formal methods of the “common practice era” (the large area of music history that encompasses the baroque, classical, and romantic periods) helped to make music more accessible. Listening to one common practice era work will help you understand how to listen to others from the same era.

The following excerpts by Franz Schubert and Johannes Brahms were written seventy years apart. If Schubert had been alive to hear Brahms’s work, the music would no doubt have been intelligible to him.

Audio Ex. 11.1: Franz Schubert, Sonata in A-Major, D. 664

Audio Ex. 11.2: Johannes Brahms, Intermezzo in A-Major, Opus 117

During the twentieth century, the common practice era came to an end. Composers intensified the individuality of their musical voices. The following works for speaker and ensemble were written within several years of each other:

Audio Ex. 11.3: Igor Stravinsky, March from L’Histoire du Soldat

Audio Ex. 11.4: Arnold Schonberg, Mondestrunken from Pierrot Lunaire

A few decades later, the following string quartets were written very close together:

Audio Ex. 11.5: Elliot Carter, String Quartet No. 1, II

Audio Ex. 11.6: John Cage, String Quartet in 4 parts, IV

Finally, the following works for two pianos were written at nearly the same time:

Audio Ex. 11.7: Steve Reich, Piano Phase

Audio Ex. 11.8: Pierre Boulez, Structures for Two Pianos

Even though these pieces share the same instrumentation and are written around the same time, they don’t share the same musical language. Listening to one piece does not help teach you how to listen to the other. Each work must be considered on its own terms.

The personalities of individual musical languages were established in a myriad of ways. Some composers, such as Harry Partch, invented their own instruments. (Partch gave his instruments such fanciful names as Cloud-Chamber Bowls, Diamond Marimba, and Chromolodeon.)

Audio Ex. 11.9: Harry Partch, “Vanity” from Eleven Intrusions

Some, like Mario Davidovsky, pioneered the use of electronic sounds. In Davidovsky’s Synchronism No. 9, live and recorded, electronically transformed violin sounds are intertwined.

Audio Ex. 11.10: Mario Davidovsky, Synchronism No. 9

Some, such as Charles Ives, blended familiar music in unusual ways. In this excerpt from his String Quartet No. 2, Ives creates a musical “discussion” in which American folk tunes from North and South are quoted in opposition to each other.

Audio Ex. 11.11: Charles Ives, String Quartet No. 2

Some, such as Lou Harrison, incorporated influences from other cultures. This excerpt from Harrison’s Song of Quetzalcoatl uses many exotic percussion instruments.

Audio Ex. 11.12: Lou Harrison, Song of Quetzalcoatl

Others, such as Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt, developed sophisticated, very carefully constructed musical methods. In this excerpt from Carter’s Variations for Orchestra, ensembles within the orchestra are characterized uniquely—the winds, for instance, are soft and slow-paced—and then layered on top of each other in a complex counterpoint.

Audio Ex. 11.13: Elliott Carter, Variations for Orchestra

Now, over a hundred years after the end of the “common practice” period, there is an enormous proliferation of musical styles. The break-up of the musical community in favor of much more personal musical languages greatly heightened ambiguity.

Absence of Pulse

A steady pulse or “backbeat,” so crucial to pop music, jazz, and much world music, provides continuity and predictability: You tap your feet to the beat.

Audio Ex. 11.14: John Barry, “Into Miami” from Goldfinger soundtrack

A steady meter divides musical time into a fixed cycle of beats. Classical ballet and ballroom dancing depend on a steady meter.

Audio Ex. 11.15: Peter Tchaikovsky, “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker ballet

Removing the steady pulse or meter disrupts the musical continuity and makes events much harder to predict. There are two main ways to accomplish this: One is to make the pulse or meter erratic.

Audio Ex. 11.16: Igor Stravinsky, “Sacrificial Dance” from The Rite of Spring

The second is to remove the sense of pulse and meter altogether, creating what Pierre Boulez has termed “unstriated time.” In the following example from Boulez’s Eclat, the solitary, sporadic events seem to float freely, unanchored by meter or pulse.

Audio Ex. 11.17: Pierre Boulez, Éclat

Weakening the sense of pulse or meter heightens ambiguity by removing an important frame of reference.

Unpredictable Continuity

It is frequently remarked that classical music is constantly creating expectations that encourage us to guess what will happen next. When the music is striving for maximum clarity, many of those expectations will be met. For instance, listen to the opening of J. S. Bach’s Prelude in E-flat from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, which was published in 1722. Can you predict what happens next?

Audio Ex. 11.18: J. S. Bach, Prelude No. 7 / Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I

Does the upper register continue with fast motion? Or does the lower register answer the upper with fast motion? Or do both registers move in slow values?

Now, listen to the actual continuation.

Audio Ex. 11.19: J. S. Bach, Prelude No. 7 / Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I

The first few exchanges between upper and lower registers created the expectation that the lower register will continue to imitate the upper. Sure enough, the lower register answers in fast motion, confirming our prediction.

A surprise occurs when one outcome is strongly anticipated but another one occurs. Ambiguity arises when multiple outcomes are all equally expected or no good forecast can be made. Listen to the opening of the second movement of Igor Stravinsky’s Three Pieces for String Quartet, which was published in 1922. Can you predict what happens next?

Audio Ex. 11.20: Igor Stravinsky, Three Pieces for String Quartet, II

Which of the various gestures that Stravinsky has introduced follows next? How sure are you? Here is how the music actually continues:

Audio Ex. 11.21: Igor Stravinsky, Three Pieces for String Quartet, II, continuation

This time, you were likely to have been much less confident of your answer. In the Bach example, a pattern was established: the upper voice was repeatedly answered by the lower. Stravinsky does not establish a consistent pattern, making any predictions much more uncertain. When we cannot confidently forecast what will happen in the future, ambiguity is heightened.

Minimal Exposition

In football, the quarterback announces the play in the huddle; then the offense steps up to the line of scrimmage and runs the play. In music, expository statements establish the identity of a musical idea; developmental passages put the idea into action. Most classical music operates like a football offense: an idea is first introduced, then put into action.

Audio Ex. 11.22: J. S. Bach, “Contrapunctus IX” from The Art of the Fugue

In a no-huddle offense, the quarterback calls out the plays at the line of scrimmage. Teams use the no-huddle offense to speed up the pace of the game and confuse the defense. This creates a much more ambiguous and hectic situation. It is harder to defend, because there is less time to analyze formations. Analogously, in music, when exposition is abbreviated and development intensified, ambiguity is heightened.

Audio Ex. 11.23: Milton Babbitt, Post-Partitions

In the most extreme cases, a modern work may consist exclusively of development. This is as if a team were to spend the entire game in a no-huddle offense! In such cases, the identity of the underlying material may be very difficult to perceive.

Lack of Literal Repetition

We establish our identity through our name, driver’s license, social security number, credit cards, personal belongings, habits, tastes, family, and friendships. In music, the most forceful and clear way to establish identity is through literal repetition. Literal repetition is the strongest way to make a musical idea recognizable.

Audio Ex. 11.24: Peter Tchaikovsky, “Peppermint Candy Canes” from The Nutcracker ballet

Buddhism challenges the concept of identity, considering it an illusion. We may cling to the emblems of an enduring self, but they are no more substantial than sand castles. The only permanent truth is “impermanence.” This finds a powerful correlation in one of modern music’s most radical innovations: the elimination of literal repetition. Removing literal repetition weakens any sense of a stable “musical identity” and heightens the music’s sense of impermanence and flux.

Audio Ex. 11.25: Milton Babbitt, All set for jazz ensemble

Lack of Resolution

In classical music, a dissonance is a tendency tone that is considered unstable. A dissonance demands continuation: It must resolve to a stable tone, called a consonance.

Audio Ex. 11.26: Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 1, IV

Classical music makes an essential promise: All dissonances will resolve. Sometimes, resolutions are delayed or new dissonances enter just as others are resolved. Eventually, however, the music will reach a state of repose and clarity.

Audio Ex. 11.27: Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 1, IV, continuation

In progressive modern music, dissonance is frequently intensified and sustained way beyond classical expectations.

Audio Ex. 11.28: Henry Cowell, Tiger

In addition, there is a new paradigm: Dissonances no longer must resolve. Stability and clarification are no longer guaranteed.

Audio Ex. 11.29: Gyorgy Kurtag, Twelve Microludes, XI

Nowhere is the clarity of classical music more strongly established than at the end of a work. There, the music summons its greatest powers of resolution. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 ends with an emphatic affirmation of stability.

Audio Ex. 11.30: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, IV, ending

The absence of resolution at a work’s close guarantees greater ambiguity. In the following example from Pierre Boulez’s Dérive (1984), a stable sound is sustained by the violin. The other instruments dart towards and away from this sound, never wholeheartedly coinciding with it. The effect is much more precarious than in the Beethoven example.

Audio Ex. 11.31: Pierre Boulez, Dérive

There is nothing that we can do to make Boulez’s ending sound as secure as Beethoven’s: It is inherently more ambivalent.

Heightened Dissonance

In music theory, dissonance is a functional term. To listeners, though, “dissonant” is often a value judgment, typically meaning “harsh” and “unpleasant.” Those attributes, though, are subjective and carry strong negative connotations. I would prefer a different description. Acoustically, a stable sound is more “transparent”: It is easier to identify its inner constituents. A sound with a lot of dissonance is more “opaque”: The greater the amount of dissonance, the harder it is to analyze and interpret the sound.

Audio Ex. 11.32: Gyorgy Ligeti, “Kyrie” from Requiem

It is easy to understand, then, why modern composers might heighten dissonance: not necessarily to make the music more strident but rather to increase the ambiguity by making the sounds harder to aurally decipher.

Harmonic Independence

In a family-style restaurant, everyone sitting at one table is fed the same food. As the platters are brought to the table, the guests choose their own portions; yet they are bound together by sharing the same meal. If someone were to ask about the menu of the day, there would be a clear and united answer.

The word harmony describes the notes that are sounding at the same time. In classical music, no matter how many instruments are playing, they will share the same harmony. As one harmony leads to another, the instruments will move together, partaking of the same notes. In addition to a steady pulse, harmonic coordination is the primary way that classical music coheres. Harmony is the reason that the instruments “sound good together” even when they are playing independent lines.

Audio Ex. 11.33: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 9, IV

At a salad bar, each person creates his or her own meal. One person might make one trip to the buffet; another might visit repeatedly, each time choosing different items. The diners no longer cohere in the same way: It would be impossible to know from one person’s plate what someone else was eating.

In music, the absence of harmonic coordination may create great ambiguity and complexity. Harmonic independence makes it much harder to get a “comprehensive” overview of how the instruments fit together. The third movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (1968) dramatizes this effect. In this movement, the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony is played continuously. On top of it, an elaborate collage of music and text is layered: graffiti from the walls of the Sorbonne, quotes from Samuel Beckett, excerpts from classical and modern music. Strong clashes arise because the collage elements do not agree harmonically with the Mahler.

Audio Ex. 11.34: Luciano Berio, Sinfonia

Harmonic independence does not mean that modern composers do not care how independent lines sound together. They do care, but they are trying to create ambiguity rather than clarity. Giving each instrument its own “plate of food,” which may complement others in intricate ways, leads to radically new resulting sounds.

Weak Rhetorical Reinforcement

When the winner is declared in a typical presidential election, streamers and balloons fall down from the ceiling, supporters cheer, cameras flash—all reinforcing the decisive outcome.

In classical music, united emphasis or “rhetorical reinforcement” is a primary means of creating structural clarity. In Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, the third movement continues into the fourth without a break. The boundary between the movements is marked by strong rhetorical reinforcement: The dynamics, texture, meter, and speed all change at once to herald the opening of the fourth movement.

Audio Ex. 11.35: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, III-IV

Election Night 2000 offered a different picture: No balloons fell, people milled about in a state of confusion, television announcers nervously shuffled their papers. Indeed, the country managed to peacefully sustain the uncertain outcome for the seven weeks that followed.

In progressive twentieth-century music, rhetorical reinforcement is often weak or absent. This makes the structural arrival points much more difficult to perceive. In Henri Dutilleux’s Ainsi la nuit… (1977), the individual movements are played without a pause. However, the boundaries between movements are difficult to discern because there are conflicting cues.

Audio Ex. 11.36: Henri Dutilleux, Ainsi la nuit… (1977)

Perhaps you recognized that the second movement begins with the loud gesture played a little over a minute into the excerpt. However, this gesture does not have a greater perceptual priority than other potential markers, such as the long silences. As a result, you are likely to be far less certain about the formal boundary.

In traditional ballet, music and movement typically reinforce each other: For instance, the music will reflect the change from a solo to an ensemble number. However, when composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham collaborated, they did not coordinate their work. Music and dance were combined for the first time at the premiere. This made rhetorical reinforcement highly unlikely; if it did occur, it could only be the result of chance. Thus, the method of collaboration guaranteed greater ambiguity.

Silence

Many musical traditions treat silence as the “absence of music.” Silence is almost totally absent from pop music. In classical music, it is used sparingly: It may occur as a “breath” to short phrases or as a way to clearly separate one section of the form from another (e.g., the first theme from the second theme in a sonata form). The opening of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 (1788) consists of continuous sound until the arrival of the contrasting section, which is marked by silence:

Audio Ex. 11.37: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Symphony No. 40, I

In progressive twentieth-century music, silence began to be treated as a musical material in its own right. Its musical information is limited: All we can analyze is how long it lasts. But, in seeking to heighten ambiguity, this limitation became a strength. We can read many possible meanings and inferences into silence: It is a hesitation, an interruption, a “trap door” into the unexpected.

Audio Ex. 11.38: Earl Kim, “Thither” from Then and Now

To John Cage, silence marked a musical event over which the composer had no control, which could function as a “window” into other sounds. His Imaginary Landscape No. 4 is scored for twelve radios. The performers move the frequency and volume dials according to precisely timed instructions. Cage has no control over the resulting sound: It depends entirely on what is being broadcast that day. At one performance, none of the frequencies marked in the score coincided with stations in that location, resulting in a completely silent performance.

The greater the use of silence, the greater the ambiguity.

Noise

If silence is the “absence of sound,” then noise is “indiscriminate” or “indistinguishable” sound, in which it is impossible to tell the pitches or what instruments are playing. Classical music is generally purged of noise. Exceptions such as the following are rare:

Audio Ex. 11.39: Peter Tchaikovsky, 1812 Overture

To progressive twentieth-century composers, the inherent ambiguity of noise became very attractive.

Composers incorporated noise in their music in numerous ways. Some brought the outside world into the concert hall. For instance, to create his electronic composition Finnegan’s Wake, John Cage recorded sounds in the Dublin neighborhood where a scene from James Joyce’s novel on which the piece was based occurred; he then layered these in a complex collage.

Audio Ex. 11.40: John Cage, Roaratorio

Other composers asked for standard instruments to be played in non-traditional ways. In his string quartet Black Angels (1970), George Crumb has an amplified string quartet run their fingers rapidly up and down their fingerboards, creating a sound meant to evoke the frantic buzzing of insects.

Audio Ex. 11.41: George Crumb, Black Angels

As with silence, the more noise, the greater the ambiguity.

Ambiguous Notation

The furniture from IKEA comes in a box, with a manual on how to put it together. There is room for individual touches, but the over-arching goal is to create a piece of furniture that matches the instructions.

Classical music also comes with detailed instructions. A classical score typically specifies the instrumentation, pitches and rhythms, speed, dynamics, and articulations. Not everything is marked with equal precision, leaving room for interpretation. However, the purpose of the score is to create a recognizable performance: Much more is shared between interpretations than differs. For instance, compare two performances of Beethoven’s Bagatelle, Opus 126, No. 1 (1825).

Audio Ex. 11.42: Ludwig van Beethoven, Bagatelle, Opus 126, No. 1, performed by Walter Chodak

Audio Ex. 11.43: Ludwig van Beethoven, Bagatelle, Opus 126, No. 1, performed by Mia Chung

Some modern composers sometimes sold their furniture with the barest of instructions. Compare the following two recordings.

Audio Ex. 11.44: Earle Brown, December 1952, performed by Eberhard Blum (piano), Frances-Marie Uitti (cello), & Nils Vigeland (piano)

Audio Ex. 11.45: Earle Brown, December 1952, performed by David Tudor (piano)

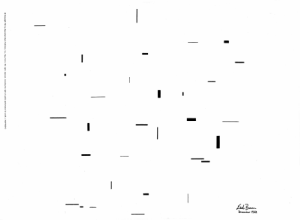

Hard as it may be to believe, those are actually two performances of the same work: Earle Brown’s December 1952. How can that possibly be? The instrumentation is different. The musical content—the pattern of sounds and silences—is totally different. Not a single detail is the same. The first performance lasts just 45 seconds. The second is actually only an excerpt of a 6-minute performance.

The sheet music score for Brown’s work is shown below:

The composer offers no suggestions as to how to interpret the image: All decisions are left up to the performer. Brown’s goal was to provide the impetus for a musical performance but not to impose an outcome. With such ambiguity in the notation, enormous variation in performance is possible.

Ambiguity in notation represents perhaps the greatest extreme reached in modern music. The more the musical text leaves open, the more it moves away from the constructive clarity of the classical era.

Something to Think About: “Something Familiar”

Some of the ideas and events that shaped modernist music also impacted popular music, though often with different musical results. Consider the characteristics of progressive modern music discussed above and think about which characteristics might be familiar to you in some of the popular music you enjoy. Which of the characteristics of progressive modernist music discussed above might you find in contemporary popular music? Alternatively, which characteristics of progressive modernist music do you find wholly alien to contemporary popular music?

Listening to Ambiguity

Tolerating the Ambiguity

In Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, two vagabonds—Vladimir and Estragon—await the arrival of a mysterious visitor, Godot. Godot’s arrival is anticipated, it is hoped for, it is repeatedly heralded—but it never happens. No matter how many times you see the play, Godot will never appear. Similarly, the ambiguities in a modern musical work are built in and can never be removed. Acknowledging this is the first step to a deeper understanding. Listeners are so often frustrated because they expect the ambiguities eventually to be clarified—if only they knew more or could listen more attentively. Doing so does not remove the ambiguities; it only makes them more acute and palpable.

Thinking Clearly about Ambiguity

Once you learn to tolerate the ambiguity, you can begin to discover its source. Are pulse and meter absent or erratic? Is dissonance heightened? Is the continuity unpredictable? Is there minimal exposition? Perpetual variation? Do noise and silence figure prominently? Any or all of these may contribute to the work’s open-endedness.

Considering the sources of the ambiguity will help you relate different pieces to each other and enable you to become more articulate about what you hear.

Be Prepared for More Personal Reactions

Progressive modern works often do not strongly direct the listener’s attention: There may not be a clear hierarchy of theme and accompaniment; structural arrival points may be more subtle or evasive. Be prepared for your reaction to be more personal, and be prepared for your perspective to change with repeated hearings as you focus on different aspects of the work.

Celebrating Ambiguity

In the same way that a Jackson Pollock drip painting will never resolve itself into a clear image, the ambiguity in a progressive modern composition is irreversible. Whether it is now or in fifty or five hundred years, the only way to appreciate such music is to learn to sustain, tolerate, and celebrate the ambiguity. There’s nothing that we can do to make the ending of Boulez’s Dérive sound like the end of Beethoven’s 5th. We cannot remove the noise from Black Angels or make a single performance of Earle Brown’s December 1952 definitive.

In an art form that is already abstract and non-verbal, heightening the ambiguity only increases the feelings of isolation and uncertainty. In addition, music is conventionally taught using concepts and terms specific to the common practice era. This training conditions listeners to certain expectations that modern music often fails to meet, leaving them baffled. To enjoy modern music, you must recognize the integrity of your own experience with the music—you must learn to trust your ears. You must also learn to abandon your pre-conceptions and listen in a style-independent way.

Most of us live comfortably in a Newtonian world, with modern advances in physics only at the periphery of our awareness. In a recent Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, the physicist Brian Greene lamented that, even one hundred years after Einstein’s insights, the Theory of Relativity has not yet infiltrated our daily experience. In life and in music, we often long for clarity. And yet, in so many ways, we are learning how deeply ambiguity is embedded in our experience and how acknowledging and tolerating it enlarges our spirit. Progressive modern music offers one of the safest ways to experience ambiguity. If we can learn to reckon with modern music with an open mind and careful attention, it may help us deal more patiently and constructively with a world filled with contradictions and paradoxes.

Compositional Styles: The “-isms”

Adapted from “The Twentieth Century and Beyond,”

Understanding Music: Past and Present

with additional content by Francis Scully

Now that we have examined all the ways that twentieth-century composers departed from earlier styles, we will explore several of the important stylistic trends or “-isms” of twentieth-century music.

Impressionism

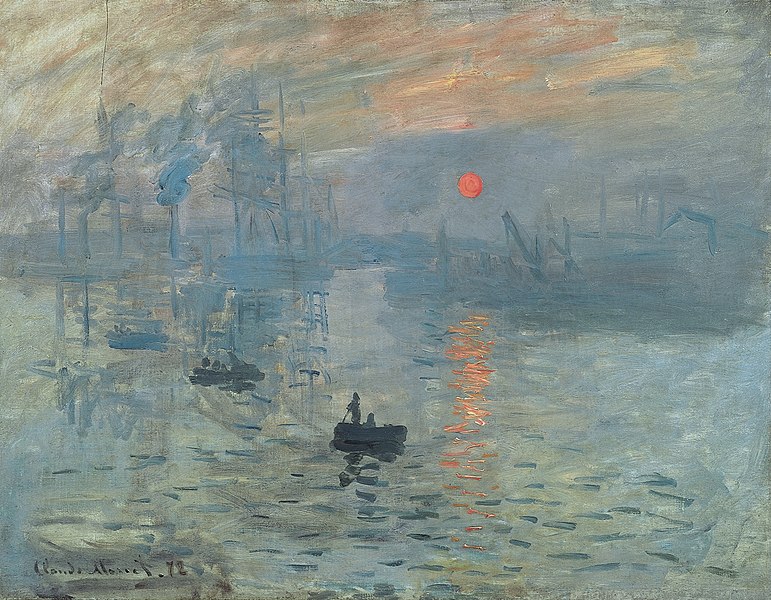

The two major composers associated with the Impressionist movement are Claude Debussy (1862–1918) and Maurice Ravel (1875–1937). Both French-born composers were searching for ways to break free from the rules of tonality that had evolved over the previous centuries. Impressionism in music, as in art, focused on the creator’s impression of an object, concept, or event. The painting below, Rouen Cathedral, by the French impressionist painter Claude Monet, suggests a church or cathedral, but it is not a clear portrait. It comprises a series of paint daubs that suggest something that we may have seen but that is slightly out of focus.

In the painting Impression Sunrise, we see how Monet distilled a scene into its most basic elements. The attention to detail of previous centuries is abandoned in favor of broad brushstrokes that are meant to capture the momentary “impression” of the scene. To Monet, the objects in the scene, such as the trees and boats, are less important than the interplay between light and water. To further emphasize this interplay, Monet pares the color palette of the painting down to draw the focus to the sunlight and the water.

Similarly, Impressionist music does not attempt to follow a story-like “program” like some Romantic period compositions. Rather, it seeks to suggest an emotion or series of emotions or perceptions. In Debussy’s orchestral work La Mer (The Sea), Debussy’s music captures the play of wind, water, and light on the ocean at different times of the day. There is no heroic individual figure in this musical picture, merely the impressions of nature without the interference of humans. While Debussy retained the large Romantic-sized orchestra and still uses mostly traditional scales and chords, the harmonies do not always resolve in traditional ways. He also makes evocative use of silence. Listen to a few minutes of the first movement of La Mer.

Video 11.1: Debussy, La Mer, performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic

Unlike composers such as Bach, Maurice Ravel was not born into a family of musicians. His father was an engineer, but one who encouraged Ravel’s musical talents. After attending the Paris Conservatory as a young man, Ravel drove a munitions truck during World War I. Throughout all this time, he composed compositions of such lushness and creativity that he became one of the most admired composers in France, along with Claude Debussy. His best-known works include Bolero, Concerto in G for Piano, La Valse, and an orchestral work entitled Daphnis et Chloé.

Daphnis et Chloé was originally conceived as a ballet in one act and three scenes and was loosely based on a Greek drama by the poet Longus. The plot on which the piece is based concerns a love affair between the title characters Daphnis and Chloe. The first two scenes of the ballet depict the abduction and escape of Chloe from a group of pirates. However, it is the third scene that has become so immortalized in the minds of music lovers ever since. “Lever du jour,” or “Daybreak,” takes place in a sacred grove and depicts the slow build of daybreak from the quiet sounds of a brook to the birdcalls in the distance. As dawn turns to day, a beautiful melody builds to a soaring climax, depicting the awakening of Daphnis and his reunion with Chloe.

After the ballet’s premier in June of 1912, the music was reorganized into two suites, the second of which features the music of “Daybreak.” Listen to the recording below and try to imagine the pastel colors of daybreak slowly giving way to the bright light of day.

Video 11.2: Daphnis et Chloé: X. Lever du jour

Listening Guide: Daphnis and Chloe, Suite No. 2: “Lever du jour”

- Composer: Maurice Ravel

- Composition: Daphnis and Chloe, Suite No. 2: “Lever du jour”

- Date: 1913

- Genre: Orchestral suite

- Form: Through-composed

- Performing forces: Orchestra/chorus

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:00 | Murmuring figures depicting a brook. Woodwinds, strings and harps, with more instruments entering periodically. Languid and flowing. Tonal, with ambiguous key centers and lush harmony typical of much Impressionistic music. |

| 0:52 | Sweeping melody reaches first climax, and then dies down slowly. Strings over murmuring accompaniment. |

| 1:09 | Strings and clarinet enter with song-like melody. Melody over murmuring strings. |

| 1:30 | Flute enters with dance-like melody. Melody over murmuring strings. |

| 1:48 | Clarinet states a contrasting melody. Melody over murmuring strings. |

| 2:13 | Chorus enters while strings continue melody. Melody over murmuring strings and “Ah” of chorus. |

| 2:53 | Melody rises to a climax and then slowly diminishes. Full Orchestra and Chorus. |

| 3:13 | Sweeping melody enters in strings to a new climactic moment. Full Orchestra. |

| 3:19 | Motif starts in low strings and then rises through the orchestra. Full Orchestra. |

| 4:05 | Chorus enters for a final climactic moment, then slowly dies away. Full Orchestra and Chorus. |

| 4:34 | Oboe enters with repeating melody. |

| 4:58 | Clarinet takes over repeating melody and the piece slows to a stop. As the piece comes to an end, the texture becomes more Spartan with fewer instruments. |

Expressionism and Serialism

While the Impressionist composers attempted to move further away from Romantic forms and Romantic harmony, some expressionist composers succeeded in completely eliminating tonal harmony and melody (music based on one specific pitch, or tonal center) from their music. The resultant sounds were often not very melodically and harmonically pleasant to hear, and as a result, the expressionist style of music did not (and still does not) appeal to the majority of audiences.

The expressionist period was not a time when composers sought to express themselves emotionally in a romantic, beautiful, or programmatic way. Instead, expressionism seems more appropriate for evoking more extreme, and sometimes even harsh, emotions. Using this experimental style of writing, composers such as Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) attempted to intentionally eliminate tonality: music that is based on scales and the progression (movement) of chords from one to another. The dissonance of this music is meant to reflect the dark recesses of the human subconscious.

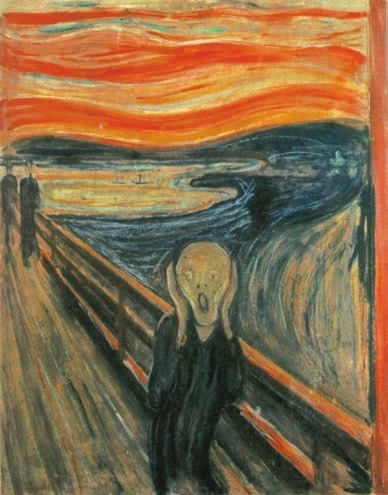

In Edvard Munch‘s famous painting The Scream, we see an excellent example of the parallel movement of expressionism taking place in the visual arts. Expressionists looked inward, specifically to the anxiety they felt towards the outside world. Expressionist paintings relied on stark colors and harsh swirling brushstrokes to convey the artist’s reaction to the ugliness of the modern world.

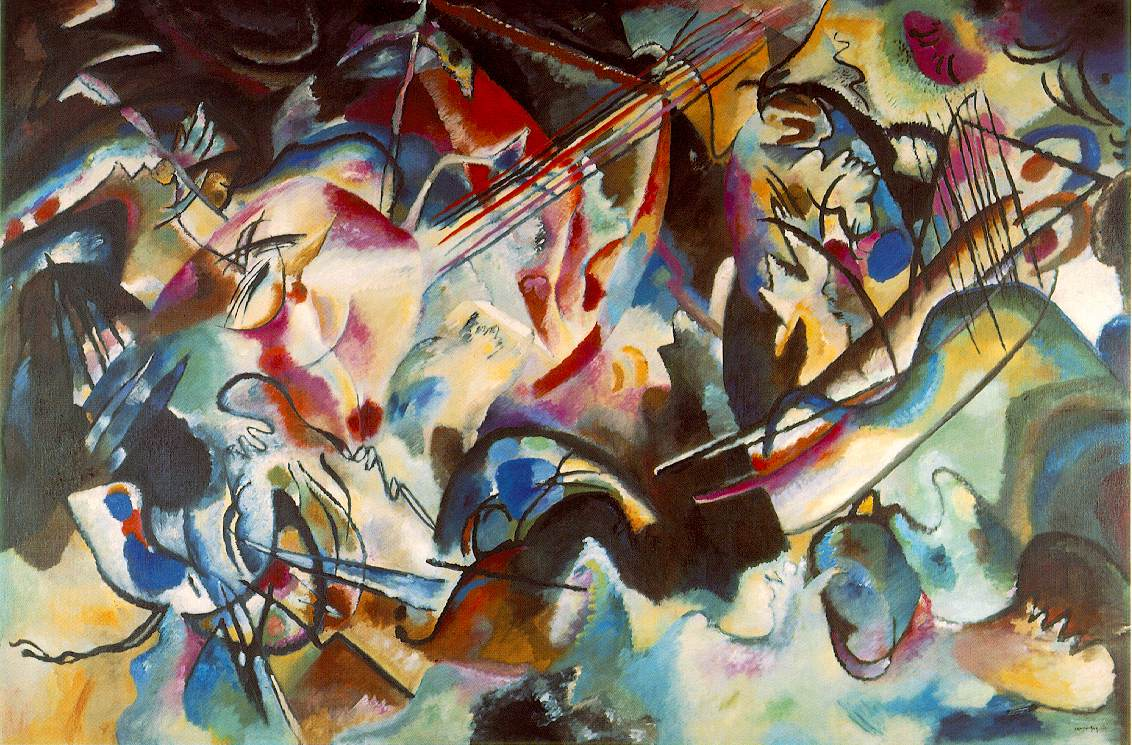

Abstract expressionism took this concept to a greater extreme by abandoning shape altogether for pure abstraction. This style is typified by the works of the American painter Jackson Pollock.

Many of the early works of Austrian-born Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) exemplify an expressionistic musical style. His music is highly dissonant and sounds quite radical when compared to earlier music, which uses dissonance only as a means to return eventually to the stasis of consonance. Schoenberg’s 1912 song cycle Pierrot Lunaire for solo soprano and five instrumentalists is one of the most famous examples of expressionist style. The piece sets 21 poems by the Belgian symbolist Albert Guiraud. Pierrot, the “sad clown,” is a stock character from the Italian street theater tradition known as Commedia dell’arte. Guiraud’s poems, full of suggestive dream and nightmare imagery, present the adventures of Pierrot as he wanders about obsessed with the moon (“lunaire”), unlucky in love, and feeling alienated from society (perhaps Pierrot also represents the figure of the artist in the twentieth century who was perpetually misunderstood).

For this song cycle, Schoenberg invents a style of singing called Sprechstimme, a kind of half-singing, half-speaking where the singer only approximates singing exact pitches. The result is a highly theatrical singing style that effectively captures the extreme psychological states.

We’ll hear two of the songs, No. 1 “Moondrunk” and No. 8 “Night.”

No. 1 “Moondrunk”: In this song, Schoenberg represents the moonlight with a dissonant descending melody in the piano. You’ll hear this repeated through the piece and shared with other instruments.

No. 8 “Night”: In this one, you hear the low instruments (cello, bass clarinet, and piano) depict the black moths of the poem. You will hear a three-note theme that is repeated again and again throughout the piece as Pierrot is overwhelmed with the arrival of night.

Read a translation of the German text and listen:

“Moondrunk” text

The wine which through our eyes we drink

Pours from the moon in waves upon us

And like a springtide

Overflows the stillness of the night.

Desires so thrilling and so sweet,

Cascading through the floods in thousands:

The wine which through our eyes we drink,

Pours from the moon in waves upon us.

The writer, so divinely moved,

Is greedy for the holy liquid,

And skyward he directs his dizzy head,

Then reeling, gulps and slurps down

The wine which through our eyes we drink.

“Night” text

Obscure, black giant moths

Killed the sun’s splendour.

A closed book of spells,

The horizon settles—hushed

From the mists of lost depths

Wafts a scent—remembrance murdered!

Obscure, black giant moths

Killed the sun’s splendour.

And from the sky earthwards

Sinking on heavy wings

Unseeable the monsters (glide)

Down into the human . . .

Obscure, black giant moths.

Video 11.3: Listen to Schoenberg, Pierrot Lunaire, Moondrunk & Night, Marianne Pousseur, Pierre Boulez, Ensemble Intercont

Part of what creates this expressionistic atmosphere in Pierrot Lunaire is that the music consciously avoids any sense of a tonal center (unlike a string quartet “in D” or a piano sonata “in B-flat,” these songs have no central pitch around which the music revolves). In later works, Schoenberg built upon this “atonal” style and developed a system whereby the twelve notes of the chromatic scale were organized into scale units that he called the twelve-tone row. These rows could then be further “serialized” by a number of different techniques. This idea of assigning values to musical information is called the 12-Tone Technique, which is a kind of Serialism. In 1921, Schoenberg composed his Piano Suite opus 25, the first composition written using the 12-tone method. Each 12-tone composition is built from a series of 12 different pitches that may be arranged in a number of different ways. The original row may be played forward, backwards (retrograde), upside down (inverted), and backwards and inverted (retrograde inversion). All of the melodies and harmonies in a 12-tone piece must be derived in some way from the original row or from fragments of the original row. This creates a sense of compositional unity and order within a highly dissonant and fragmented texture. Schoenberg’s ideas were further developed by his two famous students, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Together, the three came to be known as the Second Viennese School, in reference to the first Viennese School, which consisted of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. While these three composers were colleagues and aligned artistically, they each produced unique versions of the expressionistic style.

Primitivism in Music

The brilliant Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) was truly a cosmopolitan figure, having lived and composed in Russia, France, Switzerland, and the United States. His music influenced numerous composers, including the famed French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger. Stravinsky caused quite a stir when the ballet entitled The Rite of Spring premiered in Paris in 1913. He composed the music for a ballet that was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev and choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky, and it was so new and different that it famously caused a riot in the audience. The orchestral version (without the dancing) has become one of the most admired compositions of the twentieth century.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is an example of Primitivism. Stravinsky’s use of “primitive” sounding rhythms to depict several pagan ritual scenes makes the term Primitivism seem appropriate. Use the listening guide below to follow Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

Video 11.4: The Rite of Spring—Sacrificial Dance—Nijinsky reconstruction

Listening Guide: The Rite of Spring—Sacrificial Dance

- Composer: Igor Stravinsky

- Composition: Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance

- Date: 1913

- Genre: Ballet music

- Form: Specific passages accompany changes in choreography

- Performing forces: Full orchestra

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:15 | Strings. String section with percussion. Short, hard notes, irregular rhythms. |

| 0:47 | Strings. Winds and soft plucked stringed accompaniment. |

| 1:00 | Trombones. Winds and soft plucked stringed accompaniment. Triplet trombone fanfare over plucked string parts. Muted trumpets and strings answer. |

| 1:18 | Strings. Plucked stringed accompaniment becomes immediately loud. |

| 1:23 | Trumpet fanfare. Plucked stringed accompaniment remains loud. |

| 1:31 | French horns join fanfare section. Plucked stringed accompaniment remains loud. |

| 1:39 | Plucked stringed accompaniment becomes the melody. |

| 1:51 | Winds and soft plucked stringed accompaniment. |

| 2:06 | Violins. Scale patterns become very fast and loud. |

| 2:15 | Silence. |

| 2:17 | Strings and percussion. Restatement of section at 0:15 |

| 2:48 | Brass and percussion. Brass and percussion. Percussion faster and louder. |

| 3:18 | Horn riffs up to high notes. Add high clarinet. |

| 3:24 | Silence. |

| 3:26 | Strings and percussion. Brief restatement of section at 0:15 and 2:17 then back to material from 2:48 |

| 3:40 | Full orchestra. Multiple loud fanfare-like parts in many sections. Piece builds. |

| 3:54 | Strings. Similar to 0:07, 2:02 but more intense. |

| 4:32 | Brass. Full orchestra. Rhythmic figure carries intensity of the dance to end. |

Neoclassicism

In the decades between World War I and World War II, many composers in the Western world began to write in a style we now call neoclassicism. When composing in a Neoclassic manner, composers were looking back to the past and incorporating many of the characteristics of the classical period into their music, incorporating concepts like balance (of form and phrase), economy of material, emotional restraint, and clarity in design. They also returned to popular classical forms like the Fugue, the Concerto Grosso, and the Symphony. But these pieces are not simply imitations of an older style. They continue to push musical boundaries through crunchy modernist harmonies and experimental approaches to rhythm and meter. For composers traumatized by the devastation of World War I, neoclassicism was attractive for its anti-Romantic avoidance of emotionalism. Writing about his Octet for Winds from 1923, Stravinsky claimed, “My octet is a musical object. My Octet is not an ‘emotive’ work but a musical composition based on objective elements which are sufficient themselves…like all other objects it has weight and occupies a place in space.… I consider music by its very nature powerless to express anything: a feeling, an attitude, a psychological state, a natural phenomenon, etc.”

Listen to the first movement of Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks (1937). This is a concerto grosso modeled on the Brandenburg Concertos (1721) of J. S. Bach, but you’ll hear Stravinsky’s characteristic rhythmic technique and sharp modernist harmonies.

Video 11.5: Listen from the beginning until 4:54

Other important neoclassical works include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (1930), Pulcinella (1920), and Apollo (1928); Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 (1918) and Violin Concerto No. 2 (1935); and Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G (1931) and Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917).

The Late Twentieth Century

Minimalism

Minimalism is a movement that began in New York during the 1960s, and it stands in stark contrast to much of the music of the early twentieth century. Minimalist composers sought to distill music down to its fundamental elements. Minimalist pieces were highly consonant (unlike the atonal music of earlier composers) and often relied on the familiar sounds of triads. Instead of featuring rhythmic complexity, minimalist composers established a steady pulse and meter. And unlike twelve-tone music, which avoided repetition at all costs, minimalist composers made repetition the very focus of their music. Change was introduced very slowly through small variations of repeated patterns, and in many cases, these changes were almost imperceptible to the listener. Arguably the most famous two composers of the minimalistic style were Steve Reich (b. 1936) and Philip Glass (b. 1937). Glass composed pieces for small ensembles composed of wind instruments, voices, or organ, while Reich’s music often featured various percussion instruments.

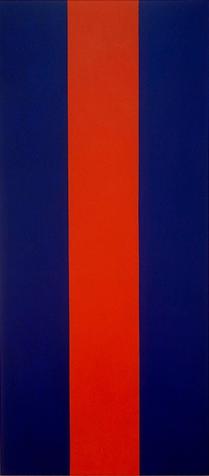

But minimalism wasn’t confined to the realm of music. In Barnett Newman‘s (1905–1970) painting (Image 7.5) Voice of Fire (1967), we see that many of these same concepts of simplification applied to the visual arts. Minimalist painters such as Newman created starkly simple artwork consisting of basic shapes, straight lines, and primary colors. This was a departure from the abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock in the same way that Steve Reich’s compositions were a departure from the complexity of Arnold Schoenberg’s music.

Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians is a composition featuring eleven related sections performed by an unorthodox ensemble consisting of mallet instruments, women’s voices, woodwinds, and percussion. Section VII below is constructed of a steady six-beat rhythmic pattern that is established at the beginning of the piece. Over this unfaltering rhythmic pattern, various instruments enter with their own repeated melodic motifs. The only real changes in the piece take place in very slow variations of rhythmic density, overall texture, and instrumental range. All of the melodic patterns in the piece fit neatly into a simple three-chord pattern, which is also repeated throughout the piece. Most minimalistic pieces follow this template of slow variations over a simple pattern. This repetition results in music with a hypnotic quality, but also with just enough change to hold the listener’s interest.

Video 11.6: Steve Reich “Music for 18 Musicians”—Section VII

Listening Guide: Steve Reich Music for 18 Musicians—Section VII

- Composer: Steve Reich

- Composition: Music for 18 Musicians

- Date: 1976

- Genre: Minimalist composition comprising eleven sections

- Performing forces: Orchestra

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:00 | Six-beat motif repeated by marimbas, mallet percussion, pianos and shaker. Steady meter is established throughout the piece. Only the texture changes. Single tonic minor chord. |

| 0:20 | Strings, woodwinds and voices enter with repeated motif, creating a more dense texture. Mallet percussion, pianos, shaker, strings, women’s voices and clarinets. |

| 0:40 | Vibraphone enters, voice, woodwind and string parts begin to change, rising and becoming more dense. Underlying three-chord motif is established and repeated. |

| 3:05 | Piece has reached its apex. From here the string, voice, and woodwind melody slowly descends and becomes less rhythmically dense. |

| 3:40 | Piece returns to original texture of mallet instruments. mallet percussion, pianos, and shaker with simple closing melody played by vibraphone. Returns to single minor chord. |

Electronic Music

Modern electronic inventions continue to change and shape our lives. Music has not been immune to these changes. Computers, synthesizers, and massive sound systems have become common throughout the western world.

Musique concrète (a French term meaning “concrete music”) is a type of electro-acoustic music that uses both electronically produced sounds (like synthesizers) and recorded natural sounds (like instruments, voices, and sounds from nature). Pierre Schaeffer (in the 1940s) was a leader in developing this technique. Unlike traditional composers, composers of musique concrète are not restricted to using rhythm, melody, harmony, instrumentation, form, and other musical elements. The video linked below offers an excellent narrative on musique concrète.

Video 11.7: Watch Musique Concrète

Below is a link to one of Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète compositions.

Video 11.8: Pierre Schaeffer — Études de bruits (1948) — YouTube

Elektronische Musik (German term meaning “electronic music”) is composed by manipulating only electronically produced sounds (not recorded sounds.) Like expressionism, both musique concrète and elektronische Musik did not last long as popular techniques. Karlheinz Stockhausen was a leader in the creation of elektronische Musik.

Listen to this example of elektronische Musik.

Video 11.9: Stockhausen—Kontakte, Work No. 12 1/2

Post-minimalism or Postmodern Eclecticism

As we’ve observed in this module, composers throughout the twentieth century, much like scientists tinkering in a laboratory, brought a sense of experimentation to musical composition, and the search for new languages of art and music resulted in some wildly musical sounds.

But where do you go once it seems as if all the radical experiments have been conducted? For many composers of the late-twentieth century, the end of modernism brought the opportunity to freely pick and choose from various styles. Nowadays, a composer might incorporate twentieth-century modernist styles, Romantic-era sounds, classical style, and baroque style and bring in elements of popular music, global music, and jazz.

John Adams (b. 1947) is probably the most well-known American composer living today. His early music was written in a minimalist style, but he has embraced 12-tone style, pop music styles, and opera and often writes for a large, Romantic-sized orchestra.

Nowadays, classical music is a global phenomenon. Composers from all over the world are writing operas, symphonies, concertos, string quartets, etc. There are composers writing exciting classical music in Africa, the Middle East, South America, all over. The 2000 film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (dir. Ang Lee) was an enormously popular film that won an academy award for Best Original Score. The music for the film includes a cello concerto written by the Chinese composer Tan Dun (b. 1957), which incorporates traditional Chinese music styles with the Western classical tradition.

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960) is another composer that represents the global trend in contemporary classical music. Golijov is Argentine of Israeli descent, and his music reflects the influences of Jewish culture and South American culture, as well as contemporary popular music.

Listen to a few minutes of Mariel, his 2008 piece for cello and electronics

Video 11.10: Maya Beiser performing “Mariel”

Twenty-first-century classical music is also no longer dominated by male composers, and there are many fascinating female composers who are making their mark in concert halls all over the world. A few names of prominent female composers today include Kaija Saariaho (Finland), Sofia Gubaidulina (Russia), Jennifer Higdon (United States), Chen Yi (China), and Julia Wolfe (United States).

In fact, the winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize in music (the highest honor for a composer in the United States) is a young female composer named Caroline Shaw (b. 1982).

At 30 years old, she was the youngest ever recipient of the award. Take a listen to the first movement of her piece Partita for 8 Voices (2012).

Video 11.11: Roomful of Teeth—Shaw: Allemande (1st movement) from Partita for 8 Voices

Film Music

Although modern audiences may no longer visit the local symphony or opera house on a regular basis, they do visit the local movie theater. In this way, symphonic music lives on in our everyday lives in the form of music for film, as well as for television shows, commercials, and video games.

More than any other form of media in the twentieth century, film has made an indelible mark on our culture. The first known public exhibition of film with accompanying sound took place in Paris in 1900, but not until the 1920s did talking pictures, or “talkies,” become commercially viable. Inevitably, part of the magic of film is due to its marriage with music. After opera, film music was the next step in the evolution of music for drama. In fact, film music follows many of the same rules established by the nineteenth-century opera and before, such as the use of overtures, leitmotifs, and incidental music. Many of the most famous themes in the history of film are known throughout the world in the same way that an aria from a famous opera would have been known to the mass audiences of the previous century. For example, who of us cannot sing the theme from Star Wars?

Unlike the music of forward-thinking twentieth-century composers such as Schoenberg and Webern, music for film is not designed to push musical boundaries; instead, it draws on compositional devices from across the vast history of Western music. Music for a film depicting a love story might rely on sweeping melodies reminiscent of Wagner or Tchaikovsky. A science fiction movie might draw on dense note clusters and unconventional synthesized sounds to evoke the strangeness of encountering beings from another world. A documentary might feature music that is emotionally detached, such as the twentieth-century minimalistic style of Philip Glass. It all depends on what style best complements the visuals.

The following example is one of the most famous melodies in cinema history, the main theme from Star Wars, composed by John Williams. Because Star Wars tells a story in a galaxy far, far away, its music should logically sound futuristic, but director George Lucas opted for an entirely different approach. He asked the film’s John Williams to compose something romantic in nature so as to ground the characters of this strange universe in something emotionally familiar. Williams achieved this goal by creating a musical landscape deeply rooted in the style of Wagner, especially in his use of heroic themes and leitmotifs. Listen to the example below and pay special note to the sense of adventure it evokes.

Video 11.12: Star Wars Main Theme (Full)

Listening Guide: Star Wars Main Theme (Full)

- Composer: John Williams

- Composition: Star Wars Main Title

- Date: 1977

- Genre: Motion Picture Soundtrack

- Performing forces: Orchestra

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:00 | Opening Fanfare: Use of perfect fourths to evoke heroism. Orchestral: trumpets and brass. Triplet figures create a sense of excitement. Opens on a loud tonic chord to convey strength. |

| 0:08 | Main Theme. High brass alternating with strings. Heroic march. Strong tonal center. |

| 1:11 | Transition to space battle music as Imperial Star Destroyer looms over a smaller ship. Ascending strings followed by lone flute solo and stabbing brass notes. Floating time followed by jarring triplet figures. Moves towards dissonance to create sense of impending danger. |

| 2:03 | Battle Music: Melody spells out a diminished chord, evoking conflict. Low brass takes over melody. Faster march creates a sense of urgency. Minor key depicts danger. |

| 2:14 | Main theme returns. Melody switches to the French horns. Heroic march. Returns to major key. |

| 3:19 | Leia’s Theme. Sweeping romantic melody in strings. Slow moving tempo. Lush romantic chords. |

| 4:06 | Main Theme returns. |

| 4:39 | Battle Theme returns. |

| 5:17 | Closing Section (Coronation Theme). Full Orchestra. Slow and majestic. Ends on a strong tonic chord. |

We talked about Leitmotifs in our chapter on nineteenth-century opera. The music of Star Wars relies heavily on this technique, and most of its characters have their own unique themes, which appear in different forms throughout the movies. Perhaps the most famous of these leitmotifs is the “Force Theme.” The link below is a compilation of the various uses of this theme throughout the trilogy.

Video 11.13: Force Theme—Star Wars Original Trilogy—Leitmotiv thru the Saga

Music for New Media

Although the movies continue to flourish in the twenty-first century, new technologies bring new media and, with it, new music. One of the fastest growing examples of new media comes in the form of video games. The music of the first commercially available video games of the 1970s was rudimentary at best. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, and video games feature complex and original musical backdrops which complement incredibly realistic graphics and game play. These games require a cinematic style of music that can adapt to the actions of the player.

Listen to the example below from the original for the Nintendo Entertainment System. Early video game music is not unlike the music of the Renaissance in that it was limited to polyphony between a small number of voices. The original NES system put significant restraints on composers, as it was only possible to sound three to four notes simultaneously, and a great deal of effort was put into getting as rich a sound as possible within these constraints. Listen below to the two versions of the main Zelda theme (called the “Overworld Theme”). Conceived by acclaimed video game composer Koji Kondo, it is one of the most famous video game themes of all time. This theme has been featured in almost all of the Legend of Zelda games. Notice how the composer uses imitative polyphony to create the illusion of a full texture.

Video 11.14: The Legend of Zelda—Overworld

Listening Guide: The Legend of Zelda—Overworld

- Composer: Koji Kondo

- Composition: The Legend of Zelda (Overworld Theme)

- Date: 1986

- Genre: Video game music

- Performing forces: Orchestra

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:00 | Introduction. Synthesized sounds. Heroic march implied by rudimentary percussion sounds. Basic chord structure implied through limited polyphony. |

| 0:07 | Main Theme. Synthesized sounds. Heroic march. Imitative polyphony creates a sense of full texture. |

Video 11.15: Skyward Sword Music—Legend of Zelda Main Theme

Listening Guide: Skyward Sword Music—Legend of Zelda Main Theme

- Composer: Koji Kondo

- Composition: The Legend of Zelda (Overworld Theme)

- Date: 1986 (2011 arrangement)

- Genre: Video game music

- Performing forces: Orchestra

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

| 0:00 | Introduction. Orchestral: Strings with brass hits. Heroic march. Rising chords create sense of anticipation. |

| 0:14 | Main Theme. Trumpets take melody followed by strings. Heroic march. |

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we explored some of the parallels between new scientific ideas in the twentieth century and the new languages of art developed by modernists. In music, composers heightened musical ambiguity and created highly individualized languages that departed significantly from the music of the “common practice era.” We then explored the general characteristics of modernist music, which included the absence of pulse, unpredictable continuity, minimal exposition, a lack of literal repetition, lack of resolution, harmonic independence, heightened dissonance, weak rhetorical reinforcement, silence, noise, and ambiguous notation. We also took a closer look at some of the significant twentieth-century musical trends and their composers. We examined the Impressionist style of music and its two main composers, Ravel and Debussy. We also looked at a new approach to harmony and composition developed by Schoenberg, Berg, and others that became known as expressionism. We then briefly touched on Stravinsky’s primitivism as well as his and other composers’ foray into neoclassicism. In the late twentieth century, we saw how the minimalist composers sought to create music from its most fundamental rhythmic and melodic elements, returning to the consonant sounds of triads and the strict application of steady meter. We also looked at several approaches to electronic music. Once the twentieth-century modernist experiments had been exhausted, composers felt free to mix and match compositional techniques in a style we called post-minimalism or postmodern eclecticism. We also observed how the classical music world in the twenty-first century has become a global phenomenon and includes many exciting female composers. Finally, we looked at music for motion pictures and at one of the most recent developments in electronic and digital entertainment: music for video games.