12 Introduction to Opera

Learning Objectives

- Identify the challenges of combining drama and music and explain how operatic conventions like recitative, aria, and ensemble help make the music and the text intelligible to audiences.

- Compare and contrast the dramatic and musical attributes of recitative, aria, and ensemble.

- Explain how opera emerged in Italy in the early seventeenth century.

- Apply understanding of the conventions of opera buffa to an analysis of selected scenes from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

By Francis Scully

In this section of the course, we’ll look at a genre of music that not only tells a story (narrative, plot, characters, action, etc.) but presents that story on a stage right before our eyes. The combination of music and theater is probably as old as civilization itself, but we will look at a particular approach to storytelling through music that emerged in Italy around 1600. This genre is known as opera.

Even if you’ve never heard or attended a performance of an opera, chances are you’ve encountered some version of the essential idea in popular culture. This essential idea, our definition of opera, is a form of staged music drama in which all or part of the text is sung (Resonances, p. 544).

Opera is like a stage play (the drama part) with characters, costumes, setting, and a plot, but the characters are singing and there is accompaniment to the singing, either a full orchestra, or a band, or even just a solo piano.

If you’ve ever seen a musical (on stage or on screen) like Hamilton, Wicked, or Phantom of the Opera, you’ve seen and heard staged music drama. Other examples include Disney movies (there’s a story with characters, but it is interspersed with music) and even many music videos combine the music in the video with some kind of dramatic presentation.

How Does It Work?

Typically, the composition of an opera begins with the words. A writer would supply the text of the drama (just like if you would open a copy of Romeo and Juliet or A Streetcar Named Desire you would see the list of characters, stage directions, and the lines of spoken speech and dialogue). Then, the musical composer would take these words, known as the libretto (Italian for “little book”; the libretto is the words of an opera), and set them to music.

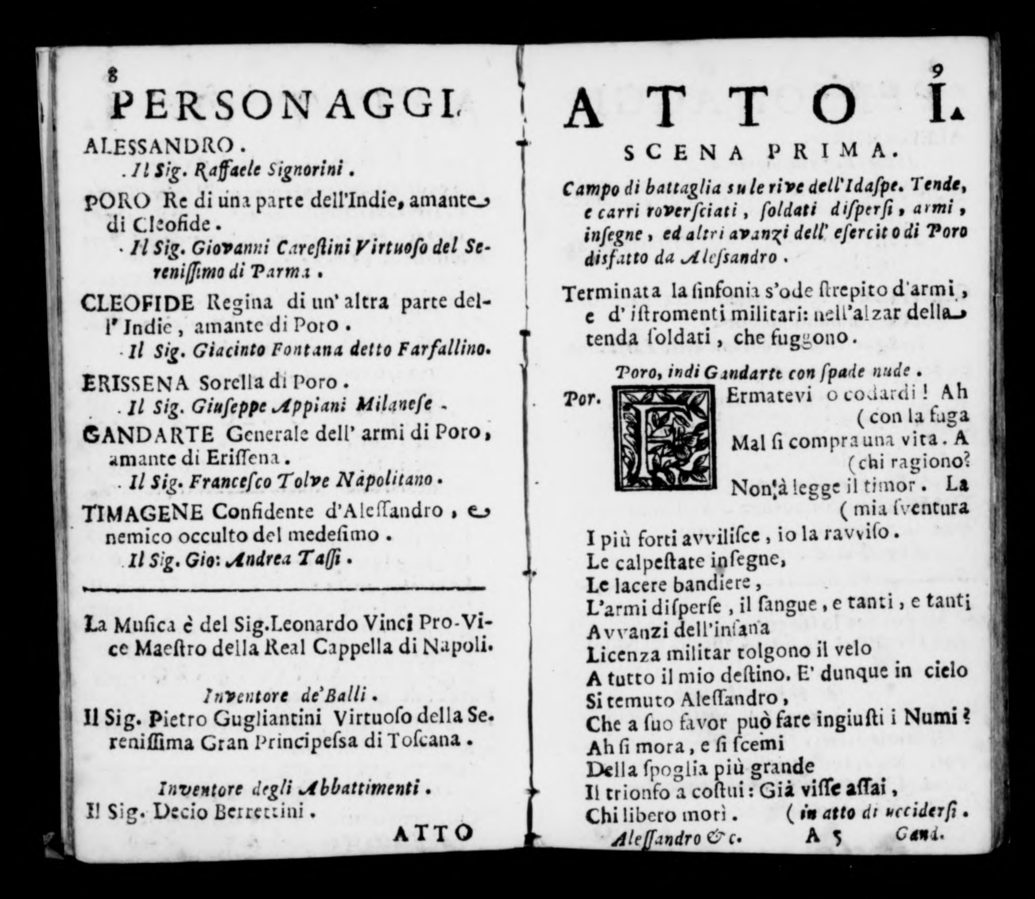

The photo below shows an example of an opera libretto in Italian. As you can see, it lists characters on the left page with the scene description and speech that characters make in the first scene. This is the “little book” that a composer would then take and set to music.

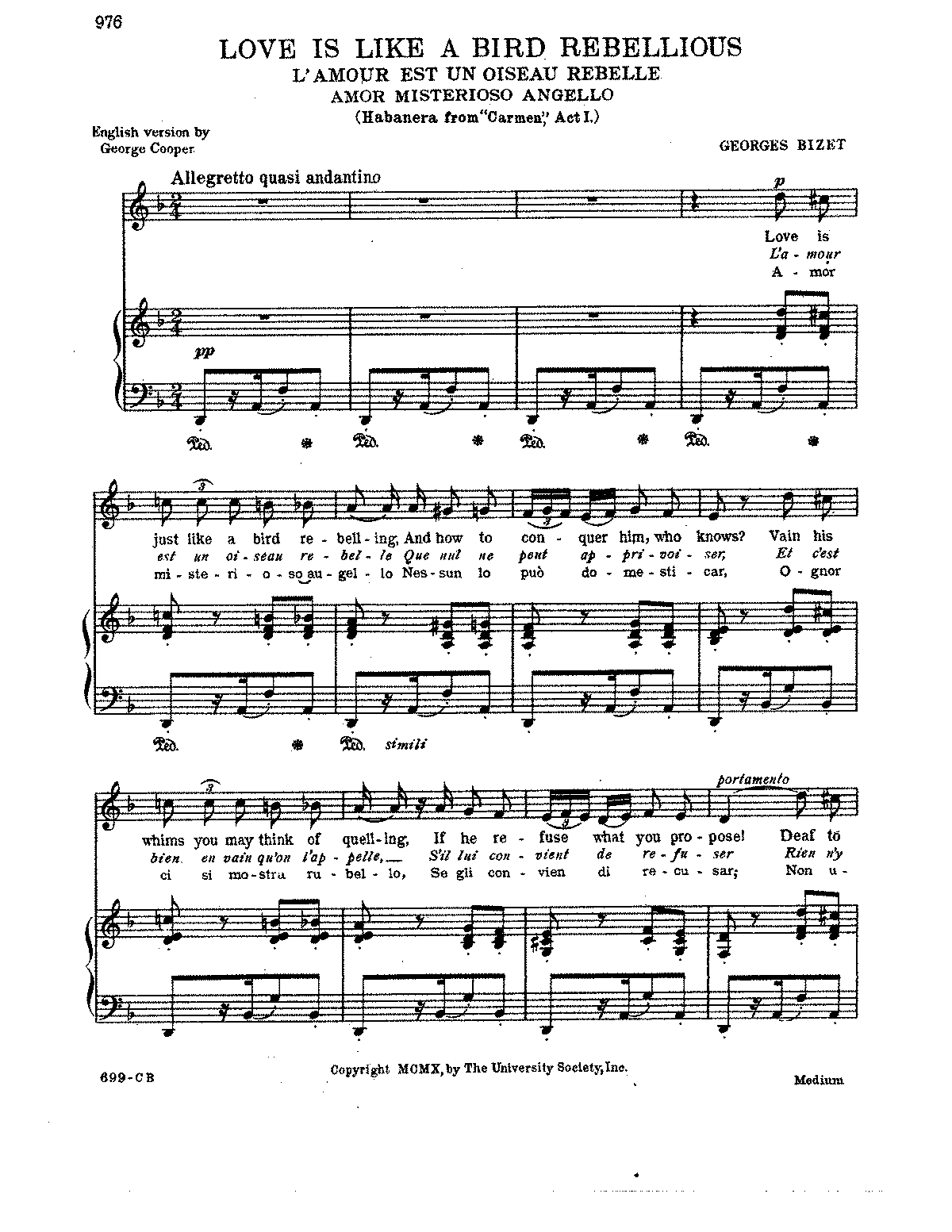

The next image shows how an operatic text (libretto) is then set to music (melody, rhythm, and accompaniment).

Finally, all of this is staged. That is, singers portray the different characters in the drama, they put on some costumes, practice singing and acting on stage, and all of this is performed before a live audience. This photo shows a still from the opera The Marriage of Figaro. Notice the costumes, the stage sets, and the elaborate lighting.

How to Present Drama in Music: The Challenge of Opera

Although combining drama and music seems like a natural fit and we encounter it a lot (again, Disney, certain music videos), combining these two different art forms proves more complicated than you might think. Consider the following issues.

The Challenge of Opera no. 1: Music is imprecise.

As we’ve observed in our explorations of Classical Period and Romantic Period music, music by itself—that is, instrumental music without words—is inherently imprecise in depicting concrete ideas or images. I may be able to write a piece of music that imitates the sounds of a thunderstorm, but I can’t create a piece of music that can tell the listener, “Cheryl is skydiving out of the airplane into the raging thunderstorm below.” I might be able to write a piece of music that generally expresses “sadness,” but I can’t write a piece that tells the listener, “Jeremy is sad because he failed to get the promotion at work that he hoped for.” These are even relatively simple scenarios, so you can imagine how challenging this would be to construct a whole plot.

Now I know what you’re thinking: “Obviously just add words to the music and you’re good to go.” Not so fast…

The Challenge of Opera no. 2: Music makes words difficult to hear and understand.

As soon as you add pitch and rhythm to words (not to mention other accompanying features like harmony, rhythmic texture, additional instruments, etc.), your brain must process more information to understand and clearly hear the words. This is part of the reason popular songs feature a lot of repetition of lyrics, so the listener can eventually get the message. In spite of this, it still doesn’t stop people from mishearing words. Don’t believe me? Check out some of these commonly misheard lyrics.

Misheard lyrics aren’t really a problem in a three-minute pop song because you can get the main idea without hearing every single word and you get a lot of repetition (and I would argue that most pop songs don’t truly tell a complex story, i.e., one that has a beginning, middle, and end, anyway). But for any complicated plot that builds on previous actions and important exchanges of dialogue, missing some critical words and actions could be deadly.

Lest you think the problems of combining music and drama come only from the music side, consider…

The Challenge of Opera no. 3: Real people don’t sing.

Have you ever stopped to consider how utterly weird Disney movies are? We watch these characters (sometimes they are animals!) walking around and talking, and suddenly they burst into song?! This is something we’ve come to expect when we watch these movies, but it’s fair to say that it’s a long way from real life. Part of the reason why people don’t sing to each other (or to themselves) highlights another fundamental difference between the real world of thought and speech and the world of music, namely…

The Challenge of Opera no. 4: Dramatic/speech-time moves faster than music-Time

Say the following sentence out loud to yourself: “Somewhere over the rainbow, way up high, there’s a land that I heard of, once in a lullaby.” Now sing these words (or hear it in your mind) to the melody of “Somewhere over the Rainbow.” The music slows down the words quite a lot. If you’re trying to create suspense and really move plot action along, music takes longer.

How to Confront Opera’s Challenges: Conventions of Opera

In order to bring music and drama together, operatic composers employ a number of conventions to make the combination of music and drama work successfully together (a convention is a standard practice that people use and come to expect in certain situations). Consider first how Disney confronts the challenges of music and drama.

Video 12.1: Scene from Beauty and the Beast | Walt Disney Animation Studios (1991) | Included on the basis of fair use as described in the Code of Best Practices for Fair Use in Open Education.

Watch this short scene from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast:

Notice that we get some important character and plot information here (Belle’s encouragement of her father, Belle’s concern that she doesn’t fit in, the fixing and success of the wood-cutting invention, the father leaves for the fair). We get a good bit of information in a short amount of time. At no point do the characters sing. To get all this information and action out quickly, the characters speak normally. There is some background music (what we call in film music “underscoring”), but the characters’ speech is not synchronized with the music at all.

Now watch another scene from the same film:

Video 12.2: Walt Disney Studios’ Belle (Reprise)—Beauty and the Beast

As in the previous scene, this scene begins with talking as Belle explains (to the animals) her disgust at the prospect of marrying Gaston. Her speech is independent of the music underneath it. At about 0:12, she suddenly joins that music and begins to sing (“Madame, Gaston can you just see…”). Now her words have a musical rhythm and pitch. The music builds as she runs into the meadow and arrives at this grand melody (“I want adventure in the great wide…”). We have a really emotional moment and a memorable melody. At this moment, we don’t require plot information/action here because Belle is just taking a moment for emotional reflection (i.e., she doesn’t want to be confined to this country village and she longs for love).

Right after this scene, the music comes to a complete stop, a horse comes in, and Belle returns to speech: “What are you doing here?” Suddenly, an important plot event is about to take place and we the audience need concrete information. Crucially, the music stops when we need speech to give us important dramatic information.

To summarize the Disney conventions (and also conventions from musical theater like Hamilton, or Oklahoma, or Phantom of the Opera): when we have important plot information and dialogue, the characters speak. When we need important emotional moments/reflection, the characters sing.

In opera, the characters are singing the whole time, but composers carefully distinguish between singing that sounds like speech and singing that sounds like song.

When composers need to introduce important plot action and dialogue, they use a style of singing known as recitative. Recitative is a speech-like style of singing that allows the singer to freely deliver the text. This style follows basic speech rhythms or speech patterns, lacks any steady rhythmic pulse, and avoids memorable melodic patterns. As you can see, the word recitative resembles the word “recite” (or “recitation”), so it sounds as much like impassioned speech as it sounds like singing.

Once you know what you’re listening for, it’s really easy to hear recitative. It sounds and looks like the characters are just having a conversation, but sort of singing it.

Video 12.3: Recitativo Don Giovanni & Leporello,

In this scene from Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787), the main character Don Giovanni (a.k.a., Don Juan) is talking with his servant Leporello. They had been separated in the previous scene, so they need to tell each other (and us, the audience) what has been going on (i.e., plot action and dialogue). The two characters have switched identities; Leporello is being chased (because everyone is after Don Giovanni), and Don Giovanni (in disguise as his servant) has just met a lovely young woman.

Watch this short exchange and just observe how the characters’ singing sounds more like the rhythms of speech than it sounds like music (there’s no “melody” here). The subtitles show the Italian text that they’re singing, so you can observe how the singers kind of fling around the words like real people talking.

Recitative allows for important plot information and dialogue to be clearly heard and understood by the audience. But when composers want to present intense emotional moments, they need the power of song. For these moments, composers use arias. An aria is the “song part” of opera in which a solo singer expresses and reflects their feelings and responses toward the dramatic situation. Unlike recitative, arias have a steady pulse and a clear, memorable melody. Words and phrases of the poetic text may be repeated. The orchestra accompanies, but instruments may also function as wordless characters that counterpoint and converse with the voice (adapted from Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, p. 97). To borrow musicologist Richard Taruskin’s formulation, arias are a kind of “emotional freeze-time” with a great tune.

Watch and listen to two very different but famous arias from opera.

The first one is from Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875), and it’s probably a tune you already know. The title character is a gypsy woman in Spain who works in a cigar factory. She seduces Don Jose, a military officer, who abandons his duties to be with her. Carmen sings this aria in her first entrance in Act I, and the music and text express her life philosophy: l’amour est un oiseau rebelle (“Love is a rebellious bird,” i.e., you can’t control love, and if you fall in love with me, you better watch out!). The music captures both the Spanish location (the music is set to a habanera rhythm, which is a Spanish dance) and the character’s sensuality.

Video 12.4: Watch “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” from Act I of Georges Bizet’s Carmen.

The next aria comes from the end of Giacomo Puccini’s 1926 opera Turandot. The character Calaf is betrothed to the cruel princess Turandot. If she can guess his name by the next morning, then he will be killed and she can avoid marrying him. If she fails to guess his name, the two must be wed. She declares to her subjects that no one is allowed to sleep in order to guess the name.

Video 12.5: Watch “Nessun dorma” from Puccini’s Turandot.

As you can see from both scenes, there is not much plot happening. The aria is really about emotional reflection, but these gorgeous melodies make for some of the most unforgettable moments.

The Birth of Opera: A Short History of Opera’s Origins

As I mentioned above, the idea of connecting music and drama has likely been around for a very, very long time, but the art form that we know as “opera” first originated in Italy around 1600. As you may recall, this is around the beginning of the Baroque era in music. There are several reasons why this Baroque era was optimal for the development of this new art form. This was a time when philosophers (and musicians) were looking back at the past, specifically ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, for information about science, politics, and the arts.

One group of intellectuals based in Florence, Italy, known as the Florentine Camerata, began reading the great ancient Greek plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. These intellectuals hypothesized (this was speculation, since they had no DVDs or YouTube files of these old performances) that the characters in these ancient plays sang the lines of poetry rather than spoke them. By singing instead of speaking, the actors heighten the words and make them even more emotionally intense. Despite the difficulties and “challenges of opera” that we mentioned above, music’s unparalleled ability to enhance the emotion of words is, in essence, the key advantage of combining music and drama.

Another element of opera that appealed to patrons of arts (that is, the dudes who paid the bills) in the Baroque era is that opera is extravagant, elaborate, and ludicrously expensive.

Opera Goes Public

The predominant style of opera in the baroque period was called (in Italian) opera seria—that is, serious opera. It originated in Italy, though it was exported around Europe. It was called “serious” because the subject material for these operas was very serious, presenting historical subjects (usually Roman history) or Greek/Roman mythology (gods and goddesses).

Opera began in Florence around 1600, but in 1637, a “public” opera house opened in Venice. This meant that anyone (or those in the moneyed classes anyway) could buy a ticket and hear an opera performance. You didn’t have to be a prince or be a part of some royal entourage. Claudio Monteverdi’s famous opera The Coronation of Poppea was a public opera composed for an opera house in Venice in 1642.

How is this new development, public opera, going to impact composers of opera? It worked the same way as a Hollywood movie. If people like your opera, they will buy tickets and they will tell their friends to go hear it. Then the opera (or the movie) will make money.

Composers had to write to impress the ticket-buying public. What did the ticket-buying public want? What you might expect: beautiful costumes and sets, intense drama and emotions, and above all, virtuoso singing full of brilliant runs, fast scales, and soaring high notes. While opera has undergone numerous developments since the 1600s, the genre’s celebration of impressive singing has never gone out of style.

Opera in the Classical Period

By the time we reach the Classical Period, the opera seria style of opera began to go out of fashion. The show-stopping virtuoso arias were impressive, but the dramatic plots were clunky, the subject matter (ancient Roman emperors or Roman mythological gods and goddesses) were boring and old-fashioned, and the frequent use of recitative grew tiresome.

A new style of opera emerged in the Classical Period known as Opera Buffa.

Opera Buffa is Italian comic opera (Buffo = Italian word for “buffoon”). Instead of ancient subjects, we get contemporary stories and down-to-earth characters, like peasant girls and soldiers. As you may gather as well, comic opera is meant to be funny. Happy resolutions to the conflict come about through amusing plot twists and schemes rather than some royal decree by an ancient god or emperor.

And what’s the secret to comedy? . . . Timing.

Comic plots in particular require events (often complicated plot events) and action to occur quickly and characters to be able to engage in rapid-fire dialogue exchanges. The old opera format of switching between recitative to aria to recitative to aria doesn’t work for comedy, so composers needed a new form that allowed them to present contrasting emotions simultaneously during one piece of music. The solution is known as ensemble.

An operatic ensemble is a number sung by two or more people. Not surprisingly, this innovation coincides with the innovation of sonata form. In sonata form, composers could present contrasting melodies and create a sense of dramatic development within a single movement. In an operatic ensemble, the music can depict different emotions simultaneously. Also, an ensemble can present sentiments changing as the drama and music unfold. An ensemble combines interesting music (melody and a steady pulse, as in an aria) with dramatic action (as in recitative).

Classical Period composers will still use the recitative-aria-recitative format, but they can add the ensemble in important dramatic moments (e.g., at the end of an act) when they want to keep the action and the music going.

Mozart is undoubtedly the master of opera buffa in the Classical Period, and we’ll get to see and hear two great scenes from his operatic masterworks. Mozart wrote many operas, but he wrote three masterpieces of Italian opera buffa in collaboration with the librettist Lorenzo da Ponte (1749-1838): The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi Fan Tutte.

The Marriage of Figaro (1786) was Mozart’s first Italian opera produced for the city of Vienna as well as his first collaboration with the librettist Lorenzo da Ponte. The libretto was based on a play of the same name written in 1778 by the French author Beaumarchais. The play is old now obviously, but in 1786 it was very contemporary and dealt with issues of class conflict. The action concerns a noble couple, Count Almaviva and his wife Countess Rosina, and their servants, Figaro and Susanna. Figaro and Susanna are hoping to get married, but the lecherous Count Almaviva wants to sleep with Susanna before they are wed. Consequently, he tries to disrupt the wedding. The countess is sad that her husband is always trying to cheat on her. Another character, the sex-obsessed adolescent page boy Cherubino, is always getting in the count’s way. See the full synopsis here: The Marriage of Figaro, Synopsis

In the finale of Act II (the second of four acts), Cherubino is in the countess’s room with Susanna and the countess. The count comes in and Cherubino hides in the closet. The count is wildly jealous (ironic, considering his own intention to cheat on the countess) and assumes that the countess is hiding a lover in her closet. When the count goes to get some tools to break open the locked door, Susanna sneaks Cherubino out the window and hides herself in the closet.

When the count and countess return, the countess still believes that Cherubino is in the closet. The count of course believes that she’s hiding a lover in the closet. The countess prepares for the count’s wrath when the closet door is opened.

Listening Guide

The scene begins with traditional recitative with the count and countess. Harpsichord accompaniment and free rhythms reflect the natural rhythms of speech.

The recitative ends, and now the orchestra enters and the ensemble begins. It begins as a duet (for two singers) and expands and expands. Mozart can brilliantly present the two different emotions side-by-side.

A few minutes into this, the count discovers in fact that Cherubino is not in the closet; instead it is Susanna! The duet then becomes a trio (three singers). How do the emotions of the character change when Susanna emerges from the closet?

If you continue watching the scene, you’ll hear how Mozart continues to add voices to this scene. Figaro enters, and then later the gardener of the estate enters, and the scene gets crazier and crazier.

Video 12.6: Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro); start the video and fast forward to about 1:15:00; watch until at least 1:24:42.

Later in the opera, you can also hear Mozart’s ability to write beautiful arias. Here’s a recitative and aria with the countess reminiscing about the good times with her husband, Act III Recit and Aria “E Susanna non vien…Dove Sono.” Fast forward to about 1:58:26 and listen up to 2:04:59.

Something to Think About

In this chapter, we examine the difficulties of combining drama and music. Arguably, most songs (either in the classical tradition or in popular music) do not necessarily trace a drama or story in the sense that the characters go through some dramatic conflict in the middle of the song that is resolved by the end of the song. Think of a song that you like and analyze its dramatic structure. (Are there characters? Is there a setting? Is there a conflict? Does the song present a resolution to the conflict?) Does the conflict and/or resolution unfold within the song or before/after the song begins? In other words, does the combination of music and words in the song really unfold a drama, or does it simply present an expanded moment of emotional reflection? Get creative: If you were to stage this song or make a movie of it, what does the character do? What does the set look like?

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we looked at the inherent difficulties of combining drama with music in the art form known as opera. Opera composers developed several conventional procedures to help make the drama intelligible to audiences without sacrificing musical interest. Recitative, which is typically used for moments of plot action and dialogue, features minimal accompaniment, and the words are delivered in a free, speech-like rhythm. An aria, on the other hand, offers a character an opportunity for solo emotional reflection. Arias are the “song” part of opera and typically feature a memorable melody, a steady pulse, and full orchestral accompaniment. Opera was born in Italy around 1600 as part of a project to imitate the power of Greek drama, but the art form has evolved through the centuries. Opera buffa, or Italian comic opera, was an operatic style that became popular during the Classical Period. Opera buffa frequently makes use of ensembles to maintain the necessary pacing for comedy while also sustaining musical interest. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro is one of the most beloved opera buffas of the Classical Period.