16 Vernacular Music of the Americas

Learning Objectives

- Describe the difference between vernacular and art music.

- Identify types of folk, popular, and classical music in the Americas.

- Discuss the origins and performing practices of both the Anglo-American Ballad and African American Spiritual.

- Discuss various genres and music styles considered popular music.

- Describe styles of American vernacular music by identifying and analyzing examples from a historical perspective.

This chapter is an adaptation of chapters from two texts: Understanding Music: Past and Present by N. Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin Jeffrey Klubal, and Elizabeth Kramer, license: CC BY-SA 4.0; and Music: Its Language, History, and Culture by Douglas Cohen, license: CC BY. It also includes original content as noted. It covers indigenous and folk music from North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean.

Introduction

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Western culture has tended to divide musical practices into two very broad fields, the vernacular and the cultivated. Vernacular refers to everyday, informal musical practices located outside the official arena of high culture—the conservatory, the concert hall, and the high church. The field of vernacular music is often further subdivided into the domains of folk music (orally transmitted and community based) and popular music (mediated for a mass audience). Cultivated music, often referred to as classical or art music, is associated with formal training and written composition. The boundaries between so-called folk, popular, and classical music are becoming increasingly blurred as we enter into the 21st century, due to the pervasive effects of mass media that have made music of all American ethnic/racial groups, classes, and regions available to everyone.

Historians and musicologists now agree that America’s most distinctive musical expressions are found, or have roots in, its vernacular music. Early immigrants from Western Europe and the slaves stolen from Africa brought with them rich traditions of oral folk music that mixed and mingled throughout the 18th and 19th centuries to develop uniquely American ballads, instrumental dance music, and spirituals. By the early 20th century, the folk blues emerged and would go on to form the foundation of much of our popular music. Beginning with 19th-century minstrel and parlor song collections, and threading through the 20th-century recordings of Tin Pan Alley song, gospel, rhythm and blues, country, rock, soul, and rap, the print and electronic media fueled the growth of American popular musical styles that today have proliferated across the globe. Jazz, sometimes considered America’s “classical” music, certainly had roots in early 20th-century folk and popular styles (see the chapter “Listening to Jazz Styles”). And many of America’s best-known classical composers including George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Duke Ellington based their extended compositions on vernacular folk and popular themes.

Native American Music

Adapted from “Appendix: Music of the World,”

Understanding Music: Past and Present, by N. Alan Clark and Thomas Heflin

Throughout history, certain cultures have had more opportunity to develop music than others. Often, the effort required to hunt, gather, or raise food has been all encompassing and has left little time for leisure or artistic pursuits. Therefore, music was only performed when the people thought it was necessary or important. Like many other cultures, traditional Native American music was normally performed as a part of important rituals meant to ask specific deities for various benefits, such as increased health, successful hunting, success in war or rain or to contact the spirit world for other reasons.

Most traditional Native American music was vocal music. It was used to tell a story, express a wish, or describe an emotional state, and it was almost always accompanied by percussion. The percussion instruments used were normally drums made of stretched animal skins, rattles, and, later, metallic bells. Vertical flutes and panpipes were sometimes used to accompany love songs. These songs had a small range with a few different pitches and were quite often based on the pentatonic scale, a five-note scale used in many different cultures. Most Native American music was not harmonized and did not have any form of harmonic accompaniment.

Video 16.1: Crown Dancer Song #1: Traditional & Spiritual Apache Songs

Video 16.2: Chikasha Poya: We Are Chickasaw, 2014

In this video, two performers talk about and demonstrate flutes used in Native American music and discuss how Native American music has adapted.

Tejano (TexMex)

Tejano or TexMex music is a blend of Central American and European influences. TexMex specifically refers to the music that grew out of both Mexico and Texas. It is dance oriented and uses European scales and chords. Instruments often include upright bass, drums, guitar, accordion, and solo vocal.

Video 16.3: Flaco Jimenez—Ay te dejo en San Antonio—”Pelicula El Infierno 2010″

The following example is based on the Western European dance called the waltz. It is in three-quarter time, with the emphasis on beat one. Listen for the ukulele, trumpet, drums, guitar, vocal harmony, and the trombone.

Video 16.4: El Coyote y su Banda Tierra Santa perform “Arboles de la Barranca”

American Folk Music

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Folk music was once thought of as being simple, old, anonymously composed music played by poor, rural, nonliterate people representing the lower strata of our society (mountain hillbillies, southern black sharecroppers, cowboys, etc.). Today scholars have expanded the field by defining folk music as orally transmitted songs and instrumental expressions that are passed on in community settings and generally show a degree of stability over time. Rather than viewing folk expressions as vanishing antiquities, this perspective suggests folk music can be a dynamic process that continues to flourish within many communities of our modern society. Using this model, popular music may be defined as mass-mediated expression that changes rapidly over time and classical/art music as musical practices centered in formal training and written composition.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American folk music collectors wrote down the words and melodies to a variety of traditional expressions, including Native American ritual songs, African American spirituals and work songs, Anglo American ballads and fiddle tunes, and western cowboy songs. Later they broadened their interest to include the traditional expressions of ethnic and immigrant communities, such as the practices of Hispanic, Irish, Jewish, Caribbean, and Chinese Americans, most of whom lived in urban areas. With the advent of portable recording technology in the 1930s, folklorists like Alan Lomax began the task of documenting America’s folk music and compiling the Archive of American Folk Song, which today, along with the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, offers students the chance to hear and study authentic regional folk styles.

Most Anglo and African American folk genres are built around relatively simple (often pentatonic) melodies, duple or triple meter time signatures, and a series of harmonic structures built around the tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords. But much of the emotional appeal of folk music comes from the grain or tension of the voice. Vocal textures vary greatly, ranging from the high, tense, nasal delivery associated with white mountain singers to the more relaxed, throaty, rough timbre of southern African American blues and spiritual singers.

In addition to studying song texts and melodies, folk music scholars have paid a great deal of attention to the social function of folk music. They seek to understand how a particular song or instrumental piece works within a specific social situation for a particular group of people. For example, how do Native American chants and African American spirituals operate within the context of a religious or worship ceremony; how are Anglo and Celtic American fiddle tunes central to Appalachian and community gatherings; how did traditional blues and ballads reflect contrasting world views of southern blacks and whites; and how do West Indian steel bands and Jewish klezmer ensembles serve as markers of cultural pride?

The self-conscious revival of folk music by middle-class urban Americans has been going on since the 1930s. During the Depression and World War II years, folk artists like Louisiana- born Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter and Oklahoma-born Woody Guthrie introduced city audiences to rural folk music, and along with left-leaning topical folk singers like Pete Seeger, they helped spawn the great folk revival of the post–World War II years. Folk music spilled into the popular arena with artists like the Kingston Trio; Burl Ives; Peter, Paul & Mary; and Bob Dylan writing and recording hit folk songs.

Anglo American Ballads

Ballads are basically folk songs that tell stories through the introduction of characters in a specific situation, the building up of dramatic tension, and the resolution of that tension. Ballads were originally brought to America by British, Scottish, and Scotch-Irish immigrants, many of whom eventually settled in the mountainous regions of the American south.

The melodies of Anglo-American ballads are simple, often built around archaic-sounding pentatonic (five note) and hexatonic (six-tone) scales that may feature large jumps or gaps between notes. Songs are traditionally sung a cappella in a free meter style or with simple guitar or banjo accompaniment. The voice is delivered in a high, tense, nasal style.

Ballads are most often set in four-line stanzas, with the second and fourth line rhyming:

I was born in West Virginia,

among the beautiful hills.

And the memory of my childhood,

lies deep within me still.

While older British and Scottish ballads found in the American South dealt with themes of ancient kings, queens, and magical happenings in faraway places, the 18th- and 19th-century ballads that developed in America tell stories of everyday folk involved in everyday life events, usually set in the present or recent past. Sentimental and tragic love stories, often involving violence and death, were common. Many American ballads express strong moral sentiments, warning listeners about the consequences of irresponsible behavior:

I courted a fair maiden,

her name I will not tell

For I have now disgraced her,

and I am doomed to hell.

It was on one beautiful evening,

the stars were shining bright

And with that faithful dagger,

I did her spirit flight.

So justice overtook me,

you all can plainly see.

My soul is doomed forever,

throughout eternity.

The sentimental and tragic themes of Anglo American ballads, along with the high-pitched, “whiny” vocal style, have survived and flourished in 20th-century popular country music.

Video 16.5: Returning Sweetheart—Sharp 98—A Pretty Fair Maid Down in the Garden—The Broken Token

Country and Western Music

From “Popular Music in the United States,”

Understanding Music: Past and Present, by N. Alan Clark and Thomas Heflin.

Country music has come to define a broad variety of musical styles encompassing Bluegrass, Hillbilly music, and Contemporary Country among others. Generally speaking, most types of music that fall under this category originated in the American South (although it also encompasses Western Swing and cowboy songs) and feature a singing style with a distinctly rural southern accent, as well as an instrumentation that favors string instruments such as the banjo, guitar, or fiddle.

Bluegrass music is a variation of country music that developed largely in the Appalachian region; it features fiddle, guitar, mandolin, bass guitar, and the five-string banjo. Often associated with Appalachia, bluegrass combines many of the song forms that are common in the region’s Scottish/English musical heritage. For example, bluegrass blends the Scottish/English ballad with blues inflections. Some bluegrass songs are fast instrumental pieces featuring amazing technique by the performers.

Video 16.6: Listen to Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys perform “Blue Grass Breakdown.”

Hillbilly music was an alternative to the jazz and dance music of the 1920s. It was portrayed as wholesome and as the music of the “good old days.” Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry radio show became a very successful weekly network radio broadcast heard nationwide. Noticing an opportunity, record companies soon opened offices in Nashville. Country music became a source of big money for producers, songwriters, and artists.

Video 16.7: The Hillbillies—“Cluck Old Hen,” 1927

Honky-tonk music developed as Hillbilly music went west to entertain in saloons called “honky tonks.” Many of the songs dealt with subjects associated with honky tonks, such as infidelity and drinking. Although the first use of the term “honky tonk” referred to a ragtime-like piano style, it later came to refer to a country combo style that became quite popular in the 1940s and 1950s.

Video 16.8: Listen to Hank Williams’s original recording from 1947

African American Spirituals and Gospel Music

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

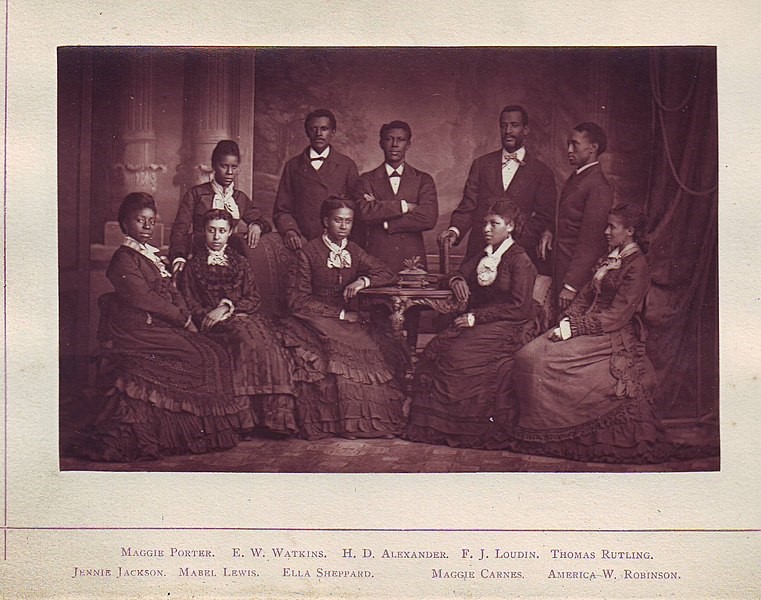

The African American Spiritual has its origins in the religious practices of 18th- and 19th-century American slaves who converted to Christianity during the great awakening revivals. The earliest spirituals were African-style ring shouts based on simple call-and-response lyrics chanted against a driving rhythm produced by clapping and foot stomping. Participants would shuffle around in a ring formation and “shout” when they felt the spirit. More complex melodies and verse/chorus structures began to evolve, reflecting the influence of European American hymn singing, and accompaniment by guitar, piano, and percussion became common. Vocal ornamentations (slides, glides, extended use of falsetto), call-and-response singing, and blues tonality characterized these folk spirituals. In the reconstruction period, black college choirs such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers arranged folk spirituals into four-part harmony, a form that became known as the concert spiritual. A blend of African and European musical practices, the spiritual epitomizes the syncretic (blended) nature of much American folk music resulting from the mixing of Africans and Europeans in the Americas.

The texts of many spirituals are taken from Old Testament themes and stories. The slaves were particularly moved by Old Testament figures like Daniel (who was saved from the lion’s den), Jonah (who was delivered from the belly of the whale), Noah (who survived the flood), and David (who defeated the giant Goliath) who struggled and triumphed over adverse conditions. The plight of the Israelites and their escape from bondage to the Promised Land was an especially powerful story retold by the spirituals:

When Israel was in Egypt’s land,

O let my people go!

Oppressed so hard they could not stand,

O let my people go!

Go Down, Moses,

Away down to Egypt’s land.

And tell old Pharaoh,

To let my people go!

The spiritual’s emphasis on redemption and deliverance in this world has led historians to suggest the songs had double meaning for the slaves—they affirmed their belief in the Bible as well as their trust that a just God would deliver them from the evils of slavery. The spirituals are thus seen as expressions of religious faith and resistance to slavery.

In the 20th century, spirituals evolved into the more urban, New Testament–centered gospel songs. Following the first “great migration” of southern African Americans to urban centers like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia in the post–World War I years, a new genre of black American sacred songs known as gospel began to appear. Unlike the anonymous folk spirituals, gospel songs were composed and copyrighted by songwriters like Thomas Dorsey and Reverend William Herbert Brewster and by the 1930s were being recorded by urban church singers. Some, like Mahalia Jackson, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Ward Singers, turned professional and reached national and international audiences through their tours and recordings. But most gospel singing remained rooted in African American church ritual and to this day can be heard in black communities throughout the north and south.

Musically, gospel is a blending of spirituals, blues, and the song sermons of the black preacher. Gospel songs are usually organized in a 16- or 32-bar verse/chorus form, often featuring call-and-response singing between a leader and a chorus. Blues tonalities are common, and singers are known for their intensive vocal ornamentations, which include bending and slurring notes, falsetto swoops, and melismas (groups of notes or tones sung across one syllable of a word). Gospel singers often end a song with a prolonged section of improvisation that combines singing, chanting, and shouting in hopes of “bringing down the spirit.” Lyrics are most often New Testament–centered, focusing on the redeeming power of Jesus and the singer’s personal relationship with the Savior.

Although gospel lyrics are strictly religious in nature, gospel music derives much of its sound from blues and jazz. Likewise, gospel music has been a source for various secular styles, including early rock and roll, soul music, and most recently gospel rap. During the Civil Rights era, the melodies of old spirituals and gospel songs were used with new lyrics expressing the need to overcome Jim Crow segregation.

Video 16.9: African American Spiritual—Give Me Jesus (Brenda Wimberly)

Video 16.10: Black Gospel—I Will Trust in the Lord (Rev. C. L. Franklin)

The Blues

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Blues music was the first significant form of secular music created by African American ex-slaves in the deep South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Growing out of earlier black spirituals, work songs, field hollers, and dance music, the blues addressed the social experiences of the ex-slaves as they struggled to establish themselves in post–Reconstruction southern culture.

Common themes addressed in early country blues songs were conflicts in love relations, loneliness, hardship, poverty, and travel. But it would be a mistake to assume that the blues were exclusively about sorrow—blues celebrated life’s ups and downs and often reflected a keen sense of ironic wit and a resolve to struggle on against difficult circumstances.

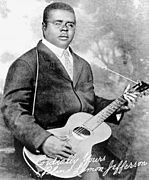

Most of the early recordings of country blues from the 1920s feature a solo male singer like Charlie Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake, or Son House accompanying himself with an acoustic guitar. But blues singers also used banjos, mandolins, fiddles, and harmonicas and often played in small ensembles that provided dance music at country juke joints. Although blues has been interpreted as a highly individualistic expression because of the solo voice and first-person text, the music was often played in social settings where African Americans danced, communed, and solidified their group identity.

Early blues lyrics were built around rhymed couplets that eventually became standardized in a 12-bar (measure) format that featured an AAB structure with a couplet being repeated twice and answered by a second couplet:

I woke up this morning,

I was feeling sad and blue. [A]

I woke up the morning,

I was feeling sad and blue. [A]

My sweet gal she left me,

got no one to sing my troubles to. [B]

The tonality is major, most often built around a 12-bar (measure) progression of the I (tonic), IV (subdominant), and V (dominant) chords. The melodic line often features bent and slurred notes, with generous use of the flatted third and seventh tones (known as “blue” notes) of the diatonic scale. The meter is usually duple (4/4), and tempos may vary from a slow drag to a fast boogie.

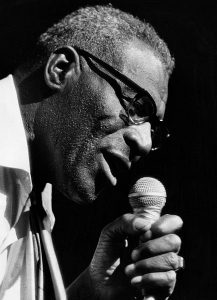

While the first blues were undoubtedly rural in origin, by the 1920s, blues music had made its way to the city. Urban singers like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith recorded and popularized sophisticated, jazz-tinged arrangements of blues in the 1920s, and composers like W. C. Handy incorporated blues forms into popular orchestral pieces like “St. Louis Blues” and “Memphis Blues.” In the post–World War II years, the country blues was electrified and transformed into rhythm and blues (R&B) by Chicago-based artists Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield), Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett), and Elmore James and Memphis bluesman B. B. King. By the mid-1950s, southern white singers like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Buddy Holly were blending rhythm and blues with elements of country music to create the new pop genre of rock and roll.

Video 16.11: Blues-Death Letter Blues (Son House)

Rock and Roll

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Perhaps America’s most influential contribution to the world of popular music has been the development of rock and roll in the 1950s. Many streams of folk and vernacular music styles, including blues, spirituals, gospel, ballads, hillbilly music, and early jazz, contributed to the evolution of rock and roll (R&R). But it was the convergence of African American rhythm and blues and Anglo American honky-tonk (country) music that led to the emergence of a distinctive new style that would dominate the field of popular music in post–World War II America.

Honky-tonk, often referred to as the voice of the downcast, working-class southern whites, was the dominant form of country music during the 1940s and early 1950s, with Hank Williams being its most famous practitioner. The music featured the tense, nasal vocal style associated with the earlier ballad tradition, accompanied by twangy guitars and fiddles, and lyrics centered on stories of loneliness and broken love relationships. Rhythm and blues was an urbanized version of older country blues that developed in cities like Memphis and Chicago during and immediately after the Second World War. Singers like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B. B. King shouted and pleaded to their audiences, backed by screaming electric guitars, amplified harmonicas, and a rhythm section of drums, bass, and piano. The music was loud, aggressive, and sensual, with lyrics boasting of sexual conquest or lamenting failed love.

The earliest rock-and–roll recordings were made by both white and black singers in the mid-1950s. The southern white artists like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bill Haley were dubbed rockabillies because their sounds were rooted in hillbilly and honky-tonk country styles. Their covers of black rhythm and blues songs like “Rock Around the Clock” (Haley) and “Good Rockin’ Tonight” (Presley) provided some of the first and most powerful examples of how white country and black R&B could blend to form the new style of R&R. From the other side of the racial divide came black R&B singers like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino, who cut their R&B sound with smoother vocals (and in Berry’s case, country-influenced guitar licks) to forge a black style of R&R that was close (and at times indistinguishable) from that of their white counterparts.

Video 16.12: Johnny Cash—Rockabilly Blues

Thus, R&R was the inevitable result of an interracial musical stew that had been simmering in the southern United States for several centuries. Its appearance in the mid-1950s was no accident, because this was precisely when independent record companies like Sun (Memphis) and Chess (Chicago) and innovative radio stations like WDIA (Memphis) were beginning to bring black vernacular music to a burgeoning baby boomer audience, and the nascent civil rights movements were increasing public awareness of black culture. R&R was a popular style created in the studio and marketed directly for legions of young, predominantly white consumers who, thanks to the relative affluence of the post–World War II years, were in search of new leisure activities.

Musically, the earliest R&R recordings were 12-bar blues played in an up-tempo 4/4 meter. Singers, black and white, would sometimes shout and snarl but were careful to articulate their words in a style smooth enough for their predominantly white audiences to comprehend. The music was backed by a strong, insistent rhythm that accented the second and fourth beat of each measure, creating a sound that was easy to dance to. Rock’s gyrating singers and sensual dancing led many middle-class Americans, black and white, to condemn it as an immoral and corrupting force. When Elvis Presley first appeared on the nationally broadcast TV variety show hosted by Ed Sullivan in 1956, the cameras would only show him from the waist up in order to avoid his sexy moves that had earned him the title “Elvis the Pelvis.”

The lyrics to the most successful early R&R songs centered on teenage romance and adventure, recounting high times cruising in automobiles, dancing at the hop, and falling in and out of love. The lyrics to sexually suggestive R&B songs covered by R&R singers were consciously cleaned up so the music would be less offensive to middle-class (black and white) teens and their parents. Eventually, the 12-bar blues form was eclipsed by the verse/chorus structure organized in 8- or 16-bar stanzas. As in earlier American popular songs, the repeated chorus was usually based on a simple but engaging melody (often referred to as the “hook”) that was easy to sing along to.

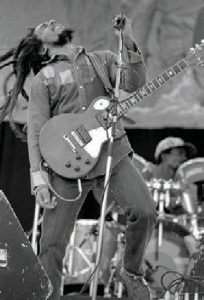

In the 1960s, groups like the Beatles and folk rock singer Bob Dylan transformed R&R by writing more sophisticated lyrics addressing the complexities of love and sexual relations, alienation in Western society, and the utopian search for a new world through drugs and counterculture activities. Both American and British rock groups of the 1960s demonstrated that popular music could provide serious social commentary that had previously been associated with the arenas of modern art and literature and the urban folk song movement. Over the past four decades, R&R (often referred to as “rock” to differentiate it from the R&R of the 1950s) has evolved in many directions (art rock, heavy metal, punk, indie), often cross-pollinating with related styles like soul, funk, disco, country, reggae, and most recently hip-hop. At times rock has served as the political voice of angry and alienated youth and at other times simply as good-time party and dance music.

Rap

Adapted from “American Vernacular Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Rap is poetry recited rhythmically over musical accompaniment. Rap is part of hip-hop culture, which emerged in the mid-1970s in the Bronx. Graffiti art and break-dance are the other major elements of hip-hop culture. Rap lyrics display clever use of words and rhymes, verbal dexterity, and intricate rhythmic patterning. Rap artists take on different roles and speak from perspectives ranging from comedic to political to dramatic, often narrating stories that reflect or comment on contemporary urban life. Rap artists may be soloists, or members of a rap group (or crew), and may recite in call-and-response format. Rap songs are generally in duple meter at a medium tempo (about 80 to 90 bpm). The musical accompaniment of rap is made up of one or several continuously repeated short phrases, each phrase combining relatively simple rhythmic patterns produced by acoustic and/or synthetic percussion instruments. Other sounds are often added for timbral variety, textural complexity, and melodic/harmonic interest. A bass line provided by electric bass guitar or synthesizer reinforces the meter and defines the tonal center.

Old School Rap (1974-1986)

Old school rap was created by DJs (disc jockeys) and one or more MCs (originally Master of Ceremonies, later Microphone Controller). DJ Kool Herc began this period, providing a portable sound system and spinning records for dances at outdoor parties and small social clubs. He noticed that b-boys and b-girls favored dancing to the “break” in a record, the short section of a song when the band drops out and the percussion continues. Using two copies of the same record on two turntables, Herc was able to make the break repeat continuously, creating the “breakbeat” that became the basic musical structure over which the MC spoke or rapped. DJs Grandmaster Flash, Jazzy Jeff, and Grand Wizard Theodore invented additional turntable techniques: “blending” different records together, scratching (manually moving the record back and forth on the turntable to create rhythmic patterns with scratchy timbres), and mixing in synthetic drum sounds and other effects. An excellent example of turntable techniques is Flash’s “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” (1981). DJs, most importantly Afrika Bambaataa, also promoted hip-hop culture through parties and other events spread by word of mouth and at venues throughout New York City.

At first MCs spoke over records in the Jamaican DJ traditions of toasting (calling out friends’ names) and boasting (touting the superiority of their own sound system and DJ skills). Both traditions became central elements of the assertive and competitive spirit of rap and hip-hop. Rap drew on other African-American sources for some of its important features: the improvisational verbal skills and call-and-response format of the dozens (an African-American verbal competition trading witty insults), the rhyming aphorisms of heavyweight champion Mohammed Ali (“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee / Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see”), the songs and vocal stylings of the great soul-funk artist James Brown, and The Last Poets, whose members spoke or chanted politically charged poems over drumming.

The first MCs to develop extended lyrical forms by rhyming over break beats were Grandmaster Caz and DJ Hollywood. The interplay of vocal and accompaniment rhythms, rhyme schemes, and phrasing are the main elements of what is known as flow. Old school flow is more regular and less syncopated than later styles. Two-line units (couplets) rhyming at the end of the lines are common during this period, such as, “Pump it up homeboy, just don’t stop / Chef Boy-ar-dee coolin’ on the pot” (The Beastie Boys). Before rap entered into the mainstream entertainment industry, portable cassette players provided a cheap and robust route of dissemination for the music throughout the city. It was the success of Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” issued on a small independent label in 1979, that brought rap to national attention and gave the genre its name. MC Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980), and “Rapture” by the pop group Blondie (1981) are also milestones in the early history of rap.

During the first part of the 1980s, the entertainment industry was slow to realize rap’s potential and it was left to entrepreneurs like Russell Simmons to popularize rap and to demonstrate its long-term commercial viability by organizing national hip-hop concert tours and producing hits by many of the most important artists of the period including L.L. Cool J, Slick Rick, and Foxy Brown. Independent films like Wild Style, Beat Street, and Style Wars introduced hip-hop to a global audience. Rap music videos began to be produced and all-rap radio stations began broadcasting. Independent labels gained ground, and rap was incorporated into the established recording and distribution industry. By 1986, hip-hop culture was the most successful popular music in the nation, and rap had developed in three general directions. Pop rap (or party rap) is light, danceable, and often humorous; it quickly became a crossover genre, generating national hits by Salt-N-Pepa (the first successful female rap group), MC Hammer, Vanilla Ice, and many others. Rock rap combines the vocalizations of rap with the sounds and rhythms of rock bands. The hip-hop trio Run-D.M.C. brought rap rock to national prominence with King of Rock (the first hip-hop platinum album, 1985). The Beastie Boys, the first white rap group, appealed to a youth market by smartly combining humor and rebellion in songs from their 1986 debut album Licensed to Ill. Rock rap set the stage for other hybrids that flourished in the 1990s, such as Rage Against the Machine and Linkin Park. Socially conscious rap portrays and comments on the urban ills of poverty, crime, drugs, and racism. The first example is Melle Mel’s “The Message” (1982), a series of bleak pictures of life and death in the ghetto.

Video 16.13: Gil Scott Heron—The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

New School Rap

New school rap dates from 1986, when Rakim and DJ Eric B introduced a vocal style that was faster and rhythmically more complex than the simple sing-song couplets of much old school rap. Writers (rap poets/performers) in the new “effusive” style, notably Nas, employed irregular poetic meters, asymmetric phrasing, and intricate rhyme schemes, all of which added depth and complexity to the flow. Much of the new music (and new styles of graffiti and dance) came from the West Coast and increasingly from the South and Midwest. Hip-hop culture was spreading to Europe and Asia as well.

The accompaniment for rap also became more complex and varied. CDs largely replaced vinyl records, and samplers became commercially available. Producers working with samplers, programmable drum machines, and synthesizers could, with the push of a button, mix and modify sounds imported from a virtually unlimited selection and so largely replaced DJs as the creators of rap’s musical accompaniment. The New York production team Bomb Squad and producers RZA and DJ Premier layered multiple samples to create dense, harmonically rich textures and grating “out of tune” combinations of sounds, while West Coast producers developed G-funk by using live instrumentation and conventional harmonies associated with funk music.

The year 1988 was an important turning point for rap. The Source, the first magazine devoted to rap and hip-hop, appeared that year, and was soon followed by Vibe, XXL, and many others. The first nationally televised rap music videos on Fab Five Freddy’s weekly show “Yo, MTV Raps!” brought hip-hop images and dances to national attention. That same year, four new rap genres emerged, partly in response to worsened social conditions in black urban communities: unemployment, drastic cutbacks in education, the crack cocaine epidemic, proliferation of deadly weapons, gang violence, militaristic police tactics, and Draconian drug laws, all leading to an explosion in the prison population. Political rap was led by writer KRS-One, with Boogie Down Productions, whose album By All Means Necessary explored police corruption, violence in the hip-hop community, and other controversial topics. On the West Coast, N.W.A. were cultivating harsh timbres and a raw, angry sound in their nihilistic tales of Los Angeles police violence and gang life in Straight Outta Compton, the first gangsta rap album. Jazz rap, characterized by use of samples from jazz classics and positive, uplifting lyrics was introduced by Gang Starr (DJ Premier and MC Guru) and hip-hop group Stetsasonic. Another answer to West Coast gangsta rap was New York hardcore rap, led by producer Marley Marl, whose hip-hop collective The Juicy Crew achieved their breakthrough with the posse track “The Symphony.” Each genre had important followers. Black nationalism informed the political lyrics of Public Enemy (led by Chuck D), whose critical and commercial success in 1988-90 proved the crossover appeal of the new wave of socially conscious rap. Houston-based gangsta rap group The Geto Boys combined ultra-violent fantasies with cutting social commentary in a blues-inflected style that came to characterize the “Dirty South” sound in their 1990 debut album. Jazz rap’s Afrocentric lyrics, fashion, and imagery were shared by important new rap artists Queen Latifah and Busta Rhymes. Latifah provided a feminist response to the often misogynist lyrics of male rappers. Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (1993) reclaimed New York’s reputation for cutting-edge hardcore rap. The minimalist production style on the album by this Staten Island group was much imitated through the next decade.

In the 1990s, a style called new jack swing, originating with producers Teddy Riley and Puff Daddy, integrated R&B into rap and softened rap’s hardcore content while retaining the edge of black street culture. Notorious B.I.G.’s “Juicy” from Ready to Die (1994) exemplifies the laid-back vocal delivery and slower tempo that characterize new jack. Lil’ Kim’s rap on “Gettin’ Money” captures the “ghettofabulous” image of the new jack rapper in lyrics that mix gats and six-shooters with Armani and Chanel. The song draws on the iconic American figure of the Mafia don to create metaphors that celebrate materialism and luxury. Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. were the most critically acclaimed and best-selling rappers during the middle of the 1990s. Shakur was murdered in 1996 and Notorious B.I.G. in 1997. In the eyes of many fans, hip-hop had lost its two greatest artists. Three important figures—Eminem, Jay-Z, and Missy Elliott—led rap into the new millennium.

Video 16.14: Common—The People (Official Music Video)

Music of the Caribbean

Adapted from “World Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Stretching from Cuba, located only 90 miles south of Florida, east and south to Trinidad, just off the coast of South America, the Caribbean is one of the most culturally diverse and musically rich regions of the world. Spanish conquest and settlement in the 17th century wiped out most of the native Carib people. English, French, and Dutch settlement followed, and sugar production became the primary industry of the area. In order to operate the labor-intensive sugar plantations, millions of African slaves were imported during the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. When slavery was abolished, large numbers of East Indians came to English-speaking islands to work the sugar plantations. Today each island has its own mix of European, African, and Asian populations. Haiti, for example, is predominantly African, while Puerto Rico boasts a mix of African and Spanish people, and Trinidad is nearly evenly split between citizens of African and East Indian ancestry. Reflecting this diverse population, the islands have developed a wide range of distinctive linguistic, religious, culinary, and musical traditions.

The concept of creolization is essential to understand the music and culture of the Caribbean. Creolization refers to the development of a distinctive new cultural form resulting from contact between two or more different cultures. Throughout the Caribbean, the blending of African and European (and occasionally East Indian) cultures has led to the emergence of new forms of language, religion, food, and of course music. With regard to music, African concepts of polyrhythm, call-and-response singing, repetition and subtle variation, along with use of percussion instruments (particularly skin drums) have blended with European melodies, harmonic accompaniment, verse/chorus song structure, and use of string and brass instruments. The diversity of Caribbean folk musical styles may be organized on a stylistic continuum, with neo-African drumming and ritual song/chant on one end and European-sounding hymn singing, military marches, social dance music, and lyrical ballads on the other. In between lie an array of truly mixed, creolized song/dance forms including the son of Cuba, the plena of Puerto Rico, the meringue of the Dominican, the mento of Jamaica, and the calypso of Trinidad. During the 20th century independence, urbanization, and emigration, along with a decline in the sugar industry and the rise of tourism, have brought sweeping changes to the Caribbean cultural landscape. The rise of mass media and international travel resulted in further mixing of Caribbean music with American and African popular styles, resulting in modern pop dance forms such as the Cuban/Puerto Rican/NYC salsa, Trinidadian socca, Jamaican reggae, Haitian konpa, and zouk from Martinique and Guadeloupe. Many of these styles have become popular in urban centers outside of the Caribbean with large populations of Island immigrants such as New York, Miami, and London. Today New York City’s dance and concert halls feature the top salsa, meringue, reggae, konpa, and socca stars, and Brooklyn’s Labor Day West Indian Carnival has grown into the largest ethnic outdoor festival in the United States.

Video 16.15: Música Cubana, Cuban Music, Son Cubano, Kiki Valera

Video 16.16: Jamaican Reggae: “One Love/People Get Ready,” Bob Marley & The Wailers, Exodus, 1977

Video 16.17: Kawe Calypso, Segundo (Costa Rica)

Pre-Columbian Music of Central and South America

Adapted from “Appendix: Music of the World,”

Understanding Music: Past and Present, by N. Alan Clark and Thomas Heflin

Pre-Columbian music in many parts of South America is similar to folk music of Native Americans as well as folk music from parts of Africa. Stretched-skin drums, wooden flutes, rattles, pentatonic-sounding scales, and vocal music are all popular in this region. The following videos include a brief discussion of the role of music in ancient Mesoamerica along with music performed on ancient ocarinas, a modern performance of traditional Aztec music, and Mayan music.

Video 16.18: Resurrecting Ancient Mesoamerican Music

Video 16.19: Aztec Music of Mexico: a sample of pre-Columbian music of the Aztecs on accurate reproductions of Aztec instruments

Video 16.20: Musica Maya: Xeet Kewel

Video 16.21: Traditional Inca music—Cusco—Peru—2018

South America

Adapted from “World Music,”

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture, by Douglas Cohen.

Until fairly recently, there had been a tendency to see the cultural traditions of the massive South American continent as monolithic. However, in the 1960s, scholars began to unravel the area’s rich tapestry of musical cultures and practices, and with the increase in recordings, the public is better able to appreciate the variety of musical traditions found here.

As many as 117 languages are spoken in the continent, in perhaps 2000 different dialects. Until the 16th century, South America boasted some of the world’s most sophisticated cultures (the most famous being, perhaps, the Incas of the Andean regions). In the 1530s, the Spanish conquistadors arrived, followed by the Portuguese. They brought with them elements of European culture, as well as Catholicism, but a variety of diseases as well that devastated parts of the indigenous population. Some indigenous traditions have remained nearly untouched until quite recently because of the geographical remoteness of the cultures that created them (vast areas of rainforest and mountain terrain had remained unexplored until quite recently). But for the most part, South American music is a fascinating mix of Spanish, Portuguese, and indigenous art forms, as well as the music of Africans who were brought to the continent as slaves. Repertories can be as diverse as the romanzas found throughout South America (historically linked to folk songs of the Spanish renaissance) and the music of the Brazilian capoeira tradition, an art form strongly influenced by African music that is accompanied by physical movements resembling martial arts.

Video 16.22: Romanza—Antonio Y Ruben

Video 16.23: Zum Zum Zum (Diego Aguilar B. Capoeira)

Argentina and Tango

In music of both its indigenous peoples and that of the Spanish conquistadors of the 16th century, as well as more recent immigrants, Argentina boasts a rich and varied heritage of art, folk, and popular traditions. Perhaps the musical genre most closely associated with this diverse country of nearly forty million is the tango. In fact, few artistic expressions are so closely associated with their country of origin as the tango is with Argentina, though variations of this popular dance arose in many Latin American countries. Perhaps no other proof is necessary than the fact that the climactic song “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina,” from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Evita, is cast in a tango style. As both a seductive dance and a musical genre, tango had lowly origins in the brothels of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital city, where it took shape during the last three decades of the 19th century, drawing on a variety of earlier Spanish and Creole forms. However, by the turn of the century, the dance and its music had begun to be accepted by the urban middle class and had been exported to the world. In the early 1910s, tango, perhaps because of its aura of the risqué (in its most popular form, it is a couples dance, with the dancers tightly clasped together and the male performing stylized moves that suggest erotic power and conquest), created a sensation in Europe and the United States. As a result, any music with the tango’s characteristic “habanera” rhythm (think of the title character’s famous aria in Bizet’s opera Carmen) began to be called a “tango,” though true Argentinean tango continued to develop as a distinctive art form. The earliest tango ensembles were made up simply of violin, flute, and guitar, though the guitar was occasionally replaced by an accordion. The turn of the century saw the incorporation of the bandoneón, a special type of 38-key accordion, as well as the piano. Later groups brought in additional string instruments, including the double bass. By the time of tango’s “Golden Age” in the 1940s, some ensembles had grown to the size of small orchestras, with full string sections, several bandoneónes, and often vocalists. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the popularity of tango in its native Argentina had been largely eclipsed by newer forms of popular and folk music. But with the rise in popularity of composer and bandoneón virtuoso Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) and his “New Tango” (see Musician Biographies), tango reached a new international audience, culminating in the wildly successful world tour of the Tango Argentino show, a stage extravaganza created in the early 1980s by Claudio Segovia and Hector Orezzoli that eventually made its way to Broadway.

Video 16.24: Argentine Tango: “Libertango” by Astor Piazzolla

Chapter Summary

Historians and musicologists now agree that America’s most distinctive musical expressions have roots in its vernacular music from native American drum circles, early immigrants from Europe, to the enslaved stolen from Africa. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, from that vantage point they have played a vital role in transmitting songs and instrumental expressions, helping to develop what is uniquely American music today. The boundaries between so-called folk, popular, and classical music are becoming increasingly blurred as we enter the 21st century, due to the pervasive effects of mass media that have made music of all American ethnic/racial groups, classes, and regions available to everyone.