2 How Music Is Created

Learning Objectives

- Identify a wide variety of sounds, comparing and contrasting them using musical elements of pitch, volume, articulation, and timbre.

- Identify important performing forces (use of the voice and instruments) of Western music.

- Define basic elements of melody, harmony, rhythm, and texture and build a vocabulary for discussing them.

- Identify basic principles and types of musical form.

- Describe musical elements and form.

- Compare and contrast categories of art music, folk music, and pop music.

- Identify ways in which humans have used music for social and expressive purposes.

Music Fundamentals

Selections from Understanding Music: Past and Present

By N. Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, and Elizabeth Kramer

Revised by Jonathan Kulp

Adapted and edited by Bonnie Le

What Is Music?

Music moves through time; it is not static. In order to appreciate music, we must remember what sounds happened and anticipate what sounds might come next. Most of us would agree that not all sounds are music! Examples of sounds not typically thought of as music include noises such as alarm sirens, dogs barking, coughing, the rumble of heating and cooling systems, and the like. But, why? One might say that these noises lack many of the qualities that we typically associate with music.

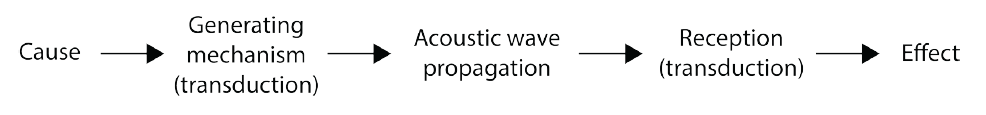

We can define music as the intentional organization of sounds in time by and for human beings. Though not the only way to define music, this definition uses several concepts important to understandings of music around the world. “Sounds in time” is the most essential aspect of the definition. Music is distinguished from many of the other arts by its temporal quality; its sounds unfold over and through time, rather than being glimpsed in a moment, so to speak. They are also perceptions of the ear rather than the eye and thus difficult to ignore as one can do by closing his or her eyes to avoid seeing something. It is more difficult for us to close our ears. Sound moves through time in waves. A sound wave is generated when an object vibrates within some medium like air or water. When the wave is received by our ears, it triggers an effect known as sound, as can be seen in the following diagram:

As humans, we also tend to be interested in music that has a plan—in other words, music that has intentional organization. Most of us would not associate coughing or sneezing or unintentionally resting our hand on a keyboard as the creation of music. Although we may never know exactly what any songwriter or composer meant by a song, most people think that the sounds of music must show at least a degree of intentional foresight.

A final aspect of the definition is its focus on humanity. Bird calls may sound like music to us; generally, the barking of dogs and hum of a heating unit do not. In each of these cases, though, the sounds are produced by animals or inanimate objects rather than by human beings; therefore, the focus of this text will only be on sounds produced by humans.

Acoustics

Acoustics is essentially “the science of sound.” It investigates how sound is produced and behaves, elements that are essential for the correct design of music rehearsal spaces and performance venues. Acoustics is also essential for the design and manufacture of musical instruments. The word itself derives from the Greek word acoustikos, which means “of hearing.” People who work in the field of acoustics generally fall into one of two groups: acousticians (those who study the theory and science of acoustics) and acoustical engineers (those who work in the area of acoustic technology). This technology ranges from the design of rooms, such as classrooms, theaters, arenas, and stadiums; to devices such as microphones, speakers, and sound-generating synthesizers; to the design of musical instruments like strings, keyboards, woodwinds, brass, and percussion.

Sound and Sound Waves

As early as the sixth century BCE (500 years before the birth of Christ), Pythagoras reasoned that strings of different lengths could create harmonious (pleasant) sounds (or tones) when played together if their lengths were related by certain ratios. Concurrent sounds in ratios of two to three, three to four, four to five, etc. are said to be harmonious. Those not related by harmonious ratios are generally referred to as noise. About 200 years after Pythagoras, Aristotle (384–322 BCE) described how sound moves through the air—like the ripples that occur when we drop a pebble in a pool of water—in what we now call waves. Sound is basically the mechanical movement of an audible pressure wave through a solid, liquid, or gas. In physiology and psychology, sound is further defined as the recognition of the vibration caused by that movement. Sound waves are the rapid movements back and forth of a medium—the gas, water, or solid—that has been made to vibrate.

Properties of Sound: Pitch

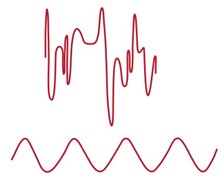

Another element that we tend to look for in music is what we call “definite pitch.” A definite pitch is a tone that is composed of an organized sound wave. A note of definite pitch is one in which the listener can easily discern the pitch. For instance, notes produced by a trumpet or piano are of definite pitch. An indefinite pitch is one that consists of a less organized wave and tends to be perceived by the listener as noise. Examples are notes produced by percussion instruments such as a snare drum.

Numerous types of music have a combination of definite pitches, such as those produced by keyboard and wind instruments, and indefinite pitches, such as those produced by percussion instruments. That said, most tunes are composed of definite pitches, and as we will see, melody is a key aspect of what most people hear as music.

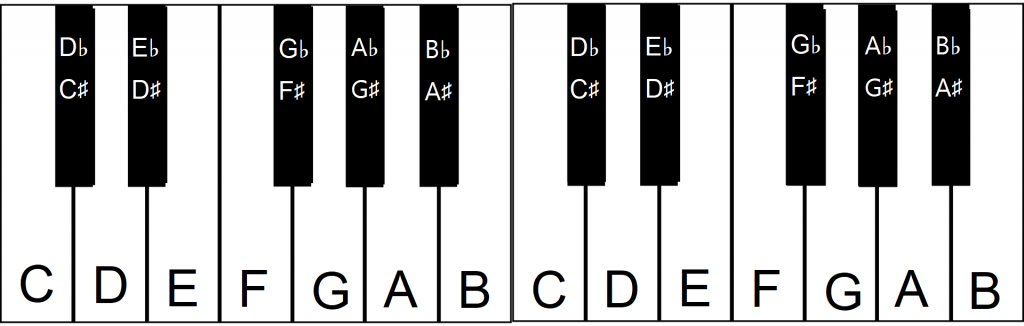

In the Western world, musicians generally refer to definite pitches by the “musical alphabet.” The musical alphabet consists of the letters A–G, repeated over and over again (…ABCDEFGABCDEFGABCDEFG…), as can be seen from this illustration of the notes on a keyboard. These notes correspond to a particular frequency of the sound wave. A pitch with a sound wave that vibrates 440 times each surface second, for example, is what most musicians would hear as an A above middle C. (Middle C simply refers to the note C that is located in the middle of the piano keyboard.) As you can see, each white key on the keyboard is assigned a particular note, each of which is named after the letters A through G. Halfway between these are black keys, which sound the sharp and flat notes used in Western music. This pattern is repeated up and down the entire keyboard.

The vibration with the lowest frequency is called the fundamental pitch. The additional definite pitches that are produced are called overtones, because they are heard above or “over” the fundamental pitch (tone). Our musical alphabet consists of seven letters repeated over and over again in correspondence with these overtones.

To return to the musical alphabet: the first partial of the overtone series is the loudest and clearest overtone heard “over” the fundamental pitch. In fact, the sound wave of the first overtone partial is vibrating exactly twice as fast as its fundamental tone. Because of this, the two tones sound similar, even though the first overtone partial is clearly higher in pitch than the fundamental pitch. If you follow the overtone series from one partial to the next, eventually you will see that all the other pitches on the keyboard might be generated from the fundamental pitch and then displaced by octaves to arrive at pitches that move by step.

The distance between any two of these notes or pitches is called an interval. On the piano, the distance between two of the longer, white key pitches is that of a step. The longer, white key pitches that are not adjacent are called leaps. The interval between C and D is that of a second, the interval between C and E that of a third, the interval between C and F that of a fourth, the interval between C and G that of a fifth, the interval between C and A is that of a sixth, the interval between C and B is a seventh, and the special relationship between C and C is called an octave.

Other Properties of Sound: Dynamics, Articulation, and Timbre

The volume of a sound is its dynamic; it corresponds with the amplitude of the sound wave. The articulation of a sound refers to how it begins and ends—for example, abruptly, smoothly, gradually, etc. The timbre of a sound is what we mean when we talk about tone color or tone quality. Because sound is somewhat abstract, we tend to describe it with adjectives typically used for tactile objects, such as “gravelly” or “smooth,” or adjectives for visual descriptions, such as “bright” or “metallic.” It is particularly affected by the ambience of the performing space—that is, by how much echo occurs and where the sound comes from. Timbre is also shaped by the equalization (EQ), or balance, of the fundamental pitch and its overtones.

The video below is a great example of two singers whose voices have vastly different timbres. How would you describe Louis Armstrong’s voice? Perhaps you would call it “rough” or “gravelly.” How would you describe Ella Fitzgerald’s voice? Perhaps it could be called “smooth” or “silky.”

Video 2.1: Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald

Music Notation

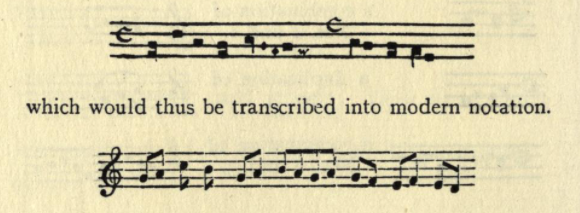

The development of music notation was absolutely critical to the rise of music that used more than just one melody. Everything that has developed in Western music after 1040 CE—from music of many independent voices (polyphonic), to solo voices with keyboard or group accompaniments, to the popular music we enjoy today—grew from this development. The staff notation system developed by Guido of Arezzo and others who followed him allowed for the accurate preservation and distribution of music. Music notation also greatly contributed to the growth, development, and evolution of the many musical styles over the past one thousand years.

Because of his contributions to the development of music notation, Guido of Arezzo is arguably the most important figure in the development of written music in the Western world. He developed a system of lines and spaces that enabled musicians to notate the specific notes in a melody. The development of music notation made it possible for composers to notate their music accurately, allowing others to perform the music exactly the way each composer intended. This ability allowed polyphonic (many voiced) music to evolve rapidly after 1040 CE. The video linked below is an excellent resource that explains Guido’s contributions in more detail.

Video 2.2: Guido of Arezzo

The popularity of staff notation after Guido paved the way for the development of a method to notate rhythm. The system of rhythmic notation we use today in Western music has evolved over many years and is explained in the following video.

Video 2.3: Watch Rhythm Notation – The basics of reading music

Old and New Notation

Western musical notation has changed a lot from its inception until the present day. Below you can see two examples. The first one is medieval chant notation (though in a modern printed book). The second example is from an 18th-century piano work by Beethoven. You can see that both examples use staves, although the chant example only has four lines, while the modern example has five. Chant notation may be unfamiliar, but it should not be too difficult to see the general contour of the melody by following the pitch indications as they go up and down the staff. Besides pitch, the modern Beethoven score also indicates precise rhythmic values and includes performance indications such as meter (“C” or “common time” in this example), tempo (“Grave” here), articulation, dynamics (fp, sf), phrasing, and fingerings (numbers above the notes). As we progress through music history we will see that composers indicate with ever-greater specificity the way they want their music to be played by the performers.

Further Reading:

Rhythmic Notation by Andrew Poushka (2003)

Visit Musical Notation on Wikipedia for a more thorough discussion of music notation and its history both in European music and in many musics of the world.

Performing Forces for Music

Music consists of the intentional organization of sounds by and for human beings. In the broadest classification, these sounds are produced by people in three ways:

- through the human voice, the instrument with which most of us are born,

- by using musical instruments, or

- by using electronic and digital equipment to generate purely electronic sounds.

The Human Voice as a Performing Force

The human voice is the most intimate of all the music instruments in that it is the one that most of us are innately equipped with. We breathe in, and, as we exhale, air rushes over the vocal cords, causing them to vibrate. Depending on the length of the vocal cords, they will tend to vibrate more slowly or more quickly, creating pitches of lower or higher frequencies.

Video 2.4: Watch “How Does Your Voicebox Work?”

Voice Ranges

In Western music, voice ranges are typically split into six categories:

Soprano

The highest female voices; sing almost exclusively above middle C (middle C being the C approximately in the middle of the range of the piano)

Mezzo-Soprano

The middle female voices; the mezzo’s vocal range lies between the soprano and the alto voice types

Alto

The lowest female voices; sing in a register around and above middle C

Tenor

The highest male voices; sing in a register around and below middle C

Baritone

The middle male voices; the baritone’s vocal range lies between the tenor and the bass voice types

Bass

The lowest male voices; sing in a low register, below middle C

The most common arrangement for an unaccompanied vocal choir is the so-called SATB texture, which uses four of the six voice types above: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Further Reading: Voice Types (Wikipedia).

Western classical music tends to use all four of these ranges, whereas melodic register and range in jazz, rock, and pop tend to be somewhat more limited. As you listen to jazz, rock, and pop, pay attention to ranges and registers used as well as any trends. Are most female jazz vocalists altos or sopranos? Do most doo‐wop groups sing in higher or lower registers? Different musical voices exhibit different musical timbres as well, as you heard earlier with Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald.

Musical Instruments as Performing Forces

Humans have been making music with bone, stone, wood, textiles, pottery, and metals for over 35,000 years. A musical instrument is any mechanism, other than the voice, that produces musical sounds. As we study jazz, rock, and pop, we will be listening to two types of musical instruments: purely acoustic instruments and electronic instruments. A purely acoustic instrument is an instrument whose sound is created and projected through natural acoustic characteristics of its media. Thus, when one hits wood or bone or stone or metal, one sends vibrations through it that might be amplified by use of a small chamber like a sound box or a gourd. When one plucks a string, one creates sound waves that might be amplified through a piece of wood or box of wood, such as one finds in an acoustic guitar or violin. As with the voice, the larger the instrument, the deeper the pitches it plays—consider, for example, the cello versus the violin. Instruments also differ in their ranges, some being able to produce a wide variety of notes, while others are much more restricted in the pitches that they can play. (For example, the piano has a range of over seven octaves, while the saxophone normally plays only two and a half.) The timbre of a sound coming from a musical instrument is affected by the materials used and the way in which the sound is produced. Based on these two characteristics, we categorize acoustic instruments into five groups: strings, wood-winds, brass, percussion, and keyboard.

Strings

Instruments whose sound is produced by setting strings in motion. These strings can be set in motion by plucking the strings with your finger (the Italian term is pizzicato) or a pick (a piece of plastic). They can also be set in motion by bowing. In bowing, the musician draws a bow across the string, creating friction and resulting in a sustained note. Most bows consist of horse hair held together on each end by a piece of wood. String examples: violins; violas; violoncellos; string bass (also known as double bass or stand-up bass); classical, acoustic, and bass guitars; harps.

Woodwinds

Instruments traditionally made of wood whose sound is generated by forcing air through a tube, thus creating a vibrating air column. This can be done in one of several ways. The air can travel directly through an opening in the instrument, as in a flute. The air can pass through an opening between a reed and a wooden or metal mouthpiece as in a saxophone or clarinet, or between two reeds (i.e., “double-reeds”) as in a bassoon or oboe. Although many woodwind instruments are in fact made of wood, there are exceptions. Instruments such as the saxophone and the modern flute are made of metal, while some clarinets are made of plastic. These instruments are still considered woodwinds because the flute was traditionally made of wood, and the saxophone and clarinet still use a wooden reed to produce the tone. Woodwind examples: flute, clarinet, saxophone, oboe, and bassoon.

Brass

Instruments traditionally made of brass or another metal (and thus often producing a “bright” or “brassy” tone) whose sound is generated by “buzzing” (vibrating the lips together) into a mouthpiece attached to a coiled tube. This “buzzing” sets the air within the tube vibrating. The pitches are normally amplified by a flared bell at the end of the tube. Brass examples: trumpet, bugle, cornet, trombone, (French) horn, tuba, and euphonium.

Percussion

Instruments that are typically hit or struck by the hand, with sticks, or with hammers, or that are shaken or rubbed. Some percussion instruments (such as the vibraphone) play definite pitches, but many play indefinite pitches. The standard drum set used in many jazz and rock ensembles, for example, consists of mostly indefinite-pitch instruments. Percussion examples: drum set, agogo bells (double bells), glockenspiel, xylophone, vibraphone, bass drum, snare or side drum, maracas, claves, cymbals, gong, triangle, and tambourine.

Keyboards

Instruments that produce sound by pressing or striking keys on a keyboard. The keys set air moving by the hammering of a string (in the case of the piano) or by the opening and closing of a pipe through which air is pushed (as in the case of the vibraphone, organ, and accordion). All of these instruments have the capacity of playing more than one musical line at the same time. Keyboard examples: piano, organ, vibraphone, and accordion. One of the earliest keyboards was the harpsichord. When the harpsichord’s keys are depressed, the strings inside the harpsichord were plucked by quill, leather, or plastic. The harpsichord was a popular keyboard instrument in the Baroque period but could not sustain its sound. The keyboard lost its popularity with the invention of the piano, which could sustain its notes and be played at different dynamic levels.

For more information and listening examples of different orchestral instruments, visit Philharmonia: Instruments. Click on the individual instruments for an introduction and demonstration of the instrument.

Non-Acoustic Instruments: Electric Sounds and Instruments

Instruments can be electric in several ways. In some cases, an acoustic instrument, such as the guitar, violin, or piano, may be played near a microphone that feeds into an amplifier. In this case, the instrument is not electric. In other cases, amplifiers are embedded in or placed onto the body of an acoustic instrument. In still other cases, acoustic instruments are altered to facilitate the amplification of their music. Thus, solid-body violins, guitars, and basses may stand in for their hollow-bodied cousins.

Another category of electronic instruments is those that produce sound through purely electronic or digital means. Synthesizers and the modern electric keyboard, as well as beat boxes, are examples of electronic instruments that use wave generators or digital signals to produce tones. Synthesizers are electronic instruments (often in keyboard form) that create sounds using basic wave forms in different combinations. The first commercially available compact synthesizers marketed for musical performance were designed and built by Dr. Robert Moog in the mid-1960s. A staple of twenty-first-century music, synthesizers are widely used in popular music and movie music. Their sounds are everywhere in our society. Synthesizers are computers that combine tones of different frequencies. These combinations of frequencies result in complex sounds that do not exist in nature.

Listen to some of the recording below of Björk, which incorporates a live band with a variety of strange and interesting synthesized sounds.

Video 2.5: Björk—Voltaic Paris HD, 2009

Solid-state electronics have enabled the synthesizer to shrink in size from its early days in the 1970s. Compare the number of electronic components in Keith Emerson’s “rig” in Figure 2.7 on the left with Chick Corea’s much smaller keyboard synthesizers on the right.

Figure 2.7b: Chick Corea, Zelt-Musik-Festival 2019 | Photographer: Ice Boy Tell | Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Synthesizers can also be used to imitate the complex sounds of real instruments, making it possible for a composer to create music and have it played without having to hire a real orchestra. Many photographs of all different types of instruments may be found using Google images.

New Recording Technologies

Today, the ability to make high-quality recordings is within the reach of anyone with a laptop and a microphone. But only a few years ago, recordings were an expensive endeavor available only to those with the financial backing of a record label. Musicians of the twenty-first century have access not only to recording technologies but also to new and cutting-edge tools that are fundamentally changing how music is created, enjoyed, and disseminated. The synthesizer discussed above can be a recording technology, but there are others, such as Auto-Tune.

Auto-Tune and Looping

Auto-Tune is a technique originally invented to correct for intonation mistakes in vocal performances. However, the technique quickly evolved into a new form of expression, allowing singers to add expressive flourishes to their singing.

Video 2.6: How Auto-Tune Works

Eventually, the technique was used to turn regular speech into music, making it possible to create music out of everyday sounds. Listen to the clip below of the musical group the Gregory Brothers, who regularly use Auto-Tune to create songs from viral Internet videos and news clips, posted to their YouTube channel, Auto-Tune the News playlist.

Looping is another technique that musicians now use to create music on the spot. The technique involves recording audio samples, which are then repeated or “looped” over and over again to a single beat. The performer then adds new loops over the old ones to create complex musical backdrops.

Video 2.7: Dub FX, “Love Someone”

Melody

The melody of a song is often its most distinctive characteristic. The ancient Greeks believed that melody spoke directly to the emotions. Melody is the part of the song that we hum or whistle, the tune that might get stuck in our heads. A more scientific definition of melody might go as follows: melody is the coherent succession of definite pitches in time. Any given melody has range, register, motion, shape, and phrases. Often, the melody also has rhythmic organization.

The first of these characteristics, range, is one that we’ve already encountered as we talked about pitch. The range of a melody is the distance between its lowest and highest notes. We talk about melodies having narrow or wide ranges. Register is also a concept we discussed in relation to pitch. Melodies can be played at a variety of registers: low, medium, high.

The music can be played smoothly and connected (an Italian term called legato is used) or the notes can be short and detached (the Italian term staccato is used). As melodies progress, they move through their given succession of pitches. Each pitch is a certain distance from the previous one and the next. Melodies that are meant to be sung tend to move by small intervals, especially by intervals of seconds or steps. A tune that moves predominantly by step is a stepwise melody. Other melodies have many larger intervals that we might describe as “skips” or “leaps.” When these leaps are particularly wide and with rapid changes in direction (that is, the melody ascends and then descends and then ascends and so forth), we say that the melody is disjunct. Conversely, a melody that moves mostly by step in a smoother manner—perhaps gradually ascending and then gradually descending—might be called conjunct.

Shape is a visual metaphor that we apply to melodies. Think of a tune that you know and like: it might be a pop tune, it might be from a musical, or it might be a song you recall from childhood. As we think back to a melody that we know, we can replay it in our mind and visualize the path that it traces.

Sing the childhood tune “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” to yourself. Now look at the musical notation for “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

Even if you can’t read music, hopefully you can see how the note heads trace an arch-like shape. Most melodies have smaller sub-sections called phrases. These phrases function somewhat like phrases in a sentence. They are complete thoughts, although generally lacking a sense of conclusion. In the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” the music corresponding with the words “Row, row, row your boat” might be heard as the first phrase and “gently down the stream” as the second phrase. “Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily” comprises a third phrase, and “life is but a dream,” a fourth, and final, phrase.

Melodies are also composed of motives. A motive is the smallest musical unit, generally a single rhythm of two or three pitches. In “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” the music set to “merrily” might be heard as a motive. Motives repeat, often in sequence. A sequence is a repetition of a motive or phrase at a different pitch level. Thus, in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” the first time you hear “merrily” is when it is at the top of the melody’s range. The next time, it is a bit lower in pitch, the next time a bit lower still, and the final time you hear the word, it is sung to the lowest pitch of the melody.

Video 2.8: Listen for sequences in “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” (2014)

Dynamics in music are the levels of loudness and softness. Composers use a type of shorthand in the written music to help the musician determine what dynamics are used when performing the music. The dynamic markings used are typically Italian terms, as the Italians created some of the earliest music notation systems. Abbreviations are often used in the written music. There are many dynamic markings. Some of the commonly used dynamics are the following: piano (p) means to play soft, forte (f) means to play loud, pianissimo (pp) is very soft, and fortissimo (ff) is very loud. To gradually increase or decrease the loudness or softness in the music, crescendo is used to gradually get louder, and decrescendo to gradually get softer.

Harmony

Most simply put, harmony is the way a melody is accompanied. It refers to the vertical aspect of music and is concerned with the different music sounds that occur in the same moment. Western music culture has developed a complex system to govern the simultaneous sounding of pitches. Some of its most complex harmonies appear in jazz, while other forms of popular music tend to have fewer and simpler harmonies.

We call a group of three or more notes or pitches that are simultaneously played or sung together a chord. Like intervals, chords can be consonant or dissonant. Consonant intervals and chords tend to sound sweet and pleasing to our ears. They also convey a sense of stability in the music. Dissonant intervals and chords tend to sound harsher to our ears and often convey a sense of tension or instability. In general, dissonant intervals and chords tend to resolve to consonant intervals and chords. Seconds, sevenths, and tritones sound dissonant and resolve to consonance. Some of the most consonant intervals are unisons, octaves, thirds, sixths, fourths, and fifths. From the perspective of physics, consonant intervals and chords are simpler than dissonant intervals and chords. However, the fact that most individuals in the Western world hear consonance as sweet and dissonance as harsh probably has as much to do with our musical socialization as with the physical properties of sound.

Listen to two examples of consonance:

Audio ex. 2.1: Bach’s Air on G String

Audio ex. 2.2: Mozart’s Symphony no. 40

Listen to two examples of dissonance:

Audio ex. 2.3: Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima

Audio ex. 2.4: Penderecki’s The Dream of Jacob

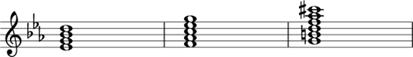

The triad is a chord that has three pitches. On top of its root pitch is stacked another pitch at the interval of a third higher than the root. On top of that second pitch, another pitch is added, another third above. If you add a fourth pitch that is a third above the previous pitch, you arrive at a seventh chord. (You may be wondering why we call chords with three notes “triads” and notes with four chords “seventh chords.” Why not “fourth chords?” The reason has to do with the fact that the extra note is the “seventh” note in the scale from which the chord is derived. We will get to scale shortly.) Seventh chords are dissonant chords. They are so common in jazz, however, that they do not always sound like they need to resolve to consonant chords as one might expect. One also finds chords with other additional tones in jazz: for example, ninth chords, eleventh chords, and thirteenth chords. These chords are related by stacking additional thirds on top of the chord. When chords are played separately instead of at the same time, we call this a broken chord, or an Italian term is used called arpeggio.

Now listen to the chords:

Audio ex. 2.5: Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Chords

Key (sometimes called “tonality”) is closely related to both melody and harmony. The key of a song or composition refers to the pitches that it uses. A key is a collection of pitches, much like you might have with a collection of stamps, bottles, etc. The most important pitch of a key is its tonic—that is, the note from which the other pitches are derived. The first note of any scale built on the first step of a scale is its tonic. For example, a composition in C major has C as its tonic; a composition in A minor has A as its tonic; a blues in the key of G has G as its tonic. When sharps or flats are placed at the beginning of each line of the music staff that notate what pitches to raise and lower throughout the music, this is called the key signature. When the music shifts from one key to another, this is called modulation.

A key is governed by its scale. A scale is a series of pitches ordered by the interval between its notes. There are a variety of types of scales. Every major scale, whether it is D major or C major or G-sharp major, has pitches related by the same intervals in the same order. Likewise, the pitches of every minor scale comprise the same intervals in the same order. The same could be said for a variety of other scales that are found in jazz, rock, and popular music, including the blues scale and the pentatonic scale. Chromatic scales use every pitch level or half step interval and are used for coloring effect in music. Major and minor scales are most often found in Western music today. The difference of sound in the major scale as opposed to the minor scale is in the perception of the sound. Major sounds relatively bright and happy. “Happy Birthday” and “Joy to the World” (the Christmas Carol) are based on the major mode.

Two excerpts featuring the major mode:

Audio ex. 2.6: Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” from Symphony No. 9

Audio ex. 2.7: Bach’s Suite No. 1 in G

Minor sounds are relatively more subdued, sad, or melancholy. The Christmas Carol “We Three Kings” is in the minor mode.

Two excerpts featuring the minor mode:

Audio ex. 2.8: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5

Audio ex. 2.9: Mahler’s “Funeral March” from Symphony No. 1 in D Major

You might note that the simplest form of the blues scale is a type of pentatonic or five-note scale. This reflects the origins of the blues in folk music; much of the folk music around the world uses pentatonic scales. Flats (b- lower a pitch a half-step interval) and sharps (#- raise a pitch a half-step interval) are used to raise and lower pitches. You might also note that the blues scale on A has a note suspended below it, an E-flat (a pitch that is a half-step higher than D and a half-step lower than E). Otherwise, it is devoid of its blue notes. Blue notes are pitches that are sometimes added to blues scales and blues pieces. The most important blues note in the key of A is E-flat. In a sense, blues notes are examples of accidentals. Accidentals are notes that are not normally found in a given key. For example, F-sharp and B-flat are accidentals in the key of C. Accidentals are sometimes called chromatic pitches: the word chromatic comes from the ancient Greek word meaning color, and accidentals and chromatic pitches add color and excitement to a composition. Chromatic scales use every pitch level or half-step interval.

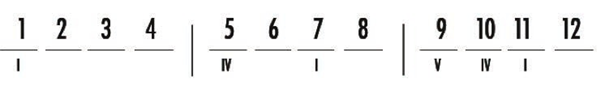

Chords can be built on every pitch of a scale. One can build seventh chords on these same pitches by simply adding pitches. In the key of C major, the C major triad is considered the tonic triad (I), because it is built on the tonic of the key. When a chord is broken up and played one note at a time in sequence, we called this an arpeggio. We call a series of chords a chord progression. One of the most important chord progressions for jazz and rock is the blues progression. In the blues, the tonic chord (I) moves to the subdominant chord (IV) and then back to the tonic chord (I) before moving to the dominant chord (V) and finally back to the tonic (I). This often happens in the space of twelve bars or measures, and thus this progression is sometimes called the twelve-bar blues.

Chord progressions play a major role in structuring jazz, rock, and popular music, cueing the listener to beginnings, middles, and ends of phrases and the song as a whole. Chord progressions in particular and harmony in general may be the most challenging aspects of music for the beginner. Hearing chords and chord progressions requires that one recognize several music phenomena at the same time. Chords may change rapidly, and a listener has to be ready to move on to the next chord as the music progresses.

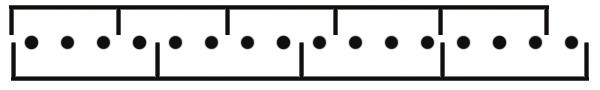

Rhythm

When you think of the word rhythm, the first thing that might pop into your head is a drum beat. But rhythm goes much deeper than that. Earlier, we defined music as intentional organization of sounds. Rhythm is the way the music is organized in respect to time. It works in tandem with melody and harmony to create a feeling of order. The most fundamental aspect of rhythm is the beat, which is the basic unit of time in music. It is the consistent pulse of the music, just like your heartbeat creates a steady, underlying pulse within your body. The beat is what you tap your feet to when you listen to music. Imagine the beat as a series of equidistant dots passing through time.

It should be noted that the beat does not measure exact time like the second hand on a clock. It is instead a fluid unit that changes depending on the music being played. The speed at which the beat is played is called the tempo. At quick tempos, the beats pass by quickly, as represented below, showing our beats pressed against each other in time.

At slow tempos, the beats pass by slowly, showing our beats with plenty of space between them.

Composers often indicate tempo markings by writing musical terms such as “Allegro,” which indicates that the piece should be played at a quick, or brisk, tempo. In other cases, composers will write the tempo markings in beats per minute (bpm) when they want more precise tempos. Either way, the tempo is one of the major factors in establishing the character of a piece. Slow tempos are used in everything from sweeping love songs to the dirges associated with sadness or death. Take, for example, Chopin’s famous funeral march from his Piano Sonata, Op. 35, No. 2:

Video 2.9: Frédéric Chopin—Funeral March (Nagai)

Fast tempos can help to evoke anything from bouncy happiness to frenzied madness. One memorable example of a fast tempo occurs in “Flight of the Bumblebee,” an orchestral interlude written by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov for his opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan, which evokes the busy buzzing of a bee.

Video 2.10: “Flight of the Bumblebee”

Basic tempo markings

By adding an -issimo ending, the word is amplified. By adding an -ino or -etto ending, the word is diminished. The beats per minute (bpm) values are rough approximations.

From slowest to fastest:

- Larghissimo – very, very slow (24 bpm [beats per minute] in a 4/4 time and under)

- Grave – very slow (25–45 bpm)

- Largo – broadly (40–60 bpm)

- Lento – slowly (45–60 bpm)

- Larghetto – rather broadly (60–66 bpm)

- Adagio – slow and stately (literally, “at ease”) (66–76 bpm)

- Adagietto – slower than andante (72–76 bpm)

- Andante – at a walking pace (76–108 bpm)

- Andantino – slightly faster than Andante (although in some cases it can be taken to mean slightly slower than andante) (80–108 bpm)

- Andante moderato – between andante and moderato (thus the name andante moderato) (92–112 bpm)

- Moderato – moderately (108–120 bpm)

- Allegretto – moderately fast (112–120 bpm)

- Allegro moderato – close to but not quite allegro (116–120 bpm)

- Allegro – fast, quickly, and bright (120–168 bpm) (molto allegro is slightly faster than allegro but always in its range)

- Vivace – lively and fast (168–176 bpm)

- Presto – very, very fast (168–200 bpm)

- Prestissimo – even faster than Presto (200 bpm and over)

Terms for tempo change:

- Rallentando – gradually slowing down

- Ritardando – gradually slowing down (but not as much as rallentando)

- Ritenuto – immediately slowing down

- Stringendo – gradually speeding up (slowly)

- Accelerando – gradually speeding up (quickly)

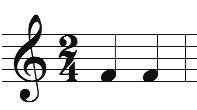

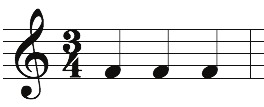

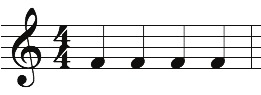

Meter

Beats are the underlying pulse behind music, while meter refers to the way in which those beats are grouped together in a piece. Each individual grouping is called a measure or a bar (referring to the vertical bar lines that divide measures in written music notation). Most music is written in either duple meter (groupings of two), triple meter (groupings of three), or quadruple meter (groupings of four). These meters are conveyed by stressing or “accenting” the first beat of each grouping. These are often referred to as strong beats, while the beats between them are referred to as weak beats.

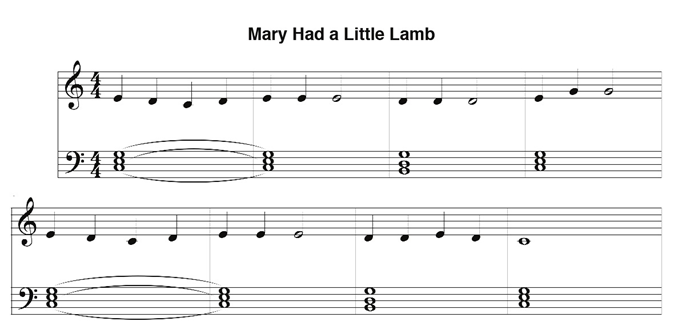

To illustrate how vital rhythm is to a piece of music, let’s investigate the simple melody “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Below, the melody and chords are conveyed through standard musical notation. The meter is indicated by the two numbers four over four. (This is known to music readers as the time signature.) This particular time signature is also known as “common time” due to the fact that it is so widely used. The top number indicates the meter, or how many beats there are per measure. The bottom number indicates which type of note in modern musical notation will represent that beat (in this case, it is the quarter note). The vertical lines are there to indicate each individual measure. As you can see, the melody on the top staff and the chords on the bottom staff line up correctly in time due to the fact that they are grouped into measures together. In this way, rhythm is the element that binds music together in time.

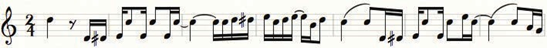

One way to add a sense of rhythmic variation to music is through the use of syncopation. Syncopation refers to the act of shifting the normal accent, usually by stressing the normally unaccented weak beats or placing the accent between the beats themselves as illustrated in Figure 2.18 below.

Syncopation is one of the defining features of ragtime and jazz and is one aspect of rhythmic bounce associated with those genres of music.

Audio ex. 2.10: The Entertainer, composer: Scott Joplin, performer: Adam Cuerden, Source: Wikimedia Commons | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

In some cases, certain types of music may feature the use of a polyrhythm, which simply refers to two or more different rhythms being played at the same time. A common polyrhythm might pit a feeling of four against a feeling of three. Polyrhythms are often associated with the music of Africa. However, they can be found in American and European music of the twentieth century, such as jazz.

Listen to the example below of Duke Ellington playing his signature song, the Billy Strayhorn composition “Take the A Train.” You will notice that the beats in the piece are grouped as four beats per measure. Pay special attention to what happens at 1:04 in the video. The horns begin to imply groupings of three beats (or triple meter) on top of the existing four beat groupings (or quadruple meter). These concurrent groupings create a sense of rhythmic tension that leads the band into the next section of the piece at 1:11 in the video.

Video 2.11: “Take the A Train”

Texture

Texture refers to the ways in which musical lines of a musical piece interact. We use a variety of general adjectives to describe musical texture, words such as transparent, dense, thin, thick, heavy, and light. We also use three specific musical terms to describe texture:

- Monophony

- Homophony

- Polyphony

Of these three terms, homophony and polyphony are most important for jazz, rock, and popular music.

Monophonic Music

Monophonic music is music that has one melodic line. This one melodic line may be sung by one person or 100 people. The important thing is that they are all singing the same melody, either in unison or in octaves. Monophony is rare in jazz, rock, and popular music. An example would be a folk melody that is sung by one person or a group of people without any accompaniment from instruments. Gregorian chant is another excellent example of monophonic music.

Homophonic Music

Homophonic music is music that has one melodic line that is accompanied by chords. A lot of rock and popular music has a homophonic texture. Anytime the tune is the most important aspect of a song, it is likely to be in homophonic texture. Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog” (1956), the Carter Family’s version of “Can the Circle be Unbroken” (1935), and Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” (1973) are relatively good examples of homophony.

Polyphonic Music

Polyphony simultaneously features two or more relatively independent and important melodic lines. Dixieland jazz and bebop are often polyphonic, as is the music of jam bands such as the Allman Bros. “Anthropology” (ca. 1946), for example—a jazz tune recorded by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and others—reflects the busy polyphony typical in bebop. Some jazz played by larger ensembles, such as big bands, is also polyphonic at points, although in this case, there is generally a strong sense of a main melody. Much of the music that we will study in this text exists somewhere between homophony and polyphony. Some music will have a strong main melody, suggesting homophony, and yet have interesting countermelodies that one would expect in polyphony. Much rap is composed of many layers of sounds, but at times those layers are not very transparent, as one would expect in polyphony.

Something to Think About

Do you listen to rap music? Can you think of a popular rap song that uses polyphony? Can you hear multiple layers of melody? Does the polyphony add to or detract from the music?

Putting It All Together or Grasping the Whole Composition

From Sound Reasoning by Anthony Brandt

Musical form is the wider perspective of a piece of music. It describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections, akin to the layout of a city divided into neighborhoods. Musical works may be classified into two formal types: A and A/B. Compositions exist in a boundless variety of styles, instrumentation, length, and content–all the factors that make them singular and personal. Yet, underlying this individuality, any musical work can be interpreted as either an A or A/B-form. An A form emphasizes continuity and prolongation. It flows, unbroken, from beginning to end. In a unified neighborhood, wander down any street and it will look very similar to any other. Similarly, in an A-form, the music has a recognizable consistency.

The other basic type is the A/B-form or binary form. Whereas A-forms emphasize continuity, A/B-forms emphasize contrast and diversity. A/B-forms are clearly broken up into sections, which differ in aurally immediate ways. The sections are often punctuated by silences or resonant pauses, making them more clearly set off from one another. Here, you travel among neighborhoods that are noticeably different from one another: The first might be a residential neighborhood, with tree-lined streets and quiet cul-de-sacs. The next is an industrial neighborhood, with warehouses and smoke-stacks. The prime articulants of form are rhythm and texture. If the rhythm and texture remain constant, you will tend to perceive an A-form. If there is a marked change in rhythm or texture, you will tend to perceive a point of contrast—a boundary, from which you pass into a new neighborhood. This will indicate an A/B-form.

Labeling the Forms

It is conventional to give alphabetic labels to the sections of a composition: A, B, C, etc. If a section returns, its letter is repeated: for instance, “A-B” or binary form and “A-B-A” or ternary form are familiar layouts in classical music. As the unbroken form, A-forms come only in a single variety. They may be long or short, but they are always “A.” As the contrast form, A/B-forms come in a boundless array of possibilities. There may be recurring sections, unique ones, or any combination of both. For instance, a Rondo—a popular form in Classical music–consists of an alternation of a recurring section and others that occur once each. It would be labeled A-B-A-C-A-D-A, etc. Many twentieth-century composers became fascinated with arch-forms: A-B-C-B-A. An on-going form, with no recurrence whatsoever, is also possible: A-B-C-D-E… Any sequence of recurring and unique sections may occur.

Understanding the layout of the city is crucial for exploring it: once you understand its topography, you know how to find its landmarks, where the places for recreation or business may lie. Similarly, determining the form of a piece will tell you a lot about it. If it is an A-form, your next focus will be on the work’s main ideas and how they are extended across the entire composition. If it is an A/B-form, your next investigations will be into the specific layout of sections and the nature of the contrasts.

Source:

Brandt, Anthony. “How Music Makes Sense,” Sound Reasoning, OpenStax CNX. Sep 17, 2019. CC BY 3.0

Examples of Binary (AB) Form and Ternary (ABA) FormBonnie Le

Video 2.12: Watch Forms 101: Binary Form from The Listener’s Guide on YouTube

Video 2.13: Watch Ternary Form Tutorial from ILoveMusicTheory on YouTube

You will notice that the two examples above both use the same melody to show binary and ternary forms. Because the melody is arranged differently in each example, it still shows different examples of form. Form would follow how it is arranged in the written music.

Form in Music

From Understanding Music: Past and Present

By N. Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, Elizabeth Kramer

Revised by Jonathan Kulp

Edited by Bonnie Le

When we talk about musical form, we are talking about the organization of musical elements—melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, timbre—in time. Because music is a temporal art, memory plays an important role in how we experience musical form. Memory allows us to hear repetition, contrast, and variation in music. And it is these elements that provide structure, coherence, and shape to musical compositions.

A composer or songwriter brings myriad experiences of music, accumulated over a lifetime, to the act of writing music. He or she has learned how to write music by listening to, playing, and studying music. He or she has picked up, consciously and/or unconsciously, a number of ways of structuring music. The composer may intentionally write music modeled after another group’s music: this happens all of the time in the world of popular music, where the aim is to produce music that will be disseminated to as many people as possible. In other situations, a composer might use musical forms of an admired predecessor as an act of homage or simply because that is “how it’s always been done.” We find this happening a great deal in the world of folk music, where a living tradition is of great importance. The music of the “classical” period (1775–1825) is rich with musical forms as heard in the works of masters such as Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In fact, form plays a vital role in most Western art music all the way into the twenty-first century.

The Twelve-Bar Blues

Many compositions that on the surface sound very different use similar musical forms. A large number of jazz compositions, for example, follow either the twelve-bar blues or an AABA form. The twelve-bar blues features a chord progression of I–IV–I–V–IV–I. Generally, the lyrics follow an AAB pattern—that is, a line of text (A) is stated once, repeated (A), and then followed by a response statement (B). The melodic idea used for the statement (B) is generally slightly different from that used for the opening phrases (A). This entire verse is sung over the I–IV–I–V–IV–I progression. The next verse is sung over the same pattern, generally to the same melodic lines, although the singer may vary the notes in various places occasionally.

Video 2.14: Listen to “Hound Dog” sung by Elvis Presley (1956) and follow the chart below to hear the blues progression

Lyrics (Chord changes indicated in brackets):

You ain’t nothin but a [I] hound dog, cryin’ all the time

You ain’t nothin but a [IV] hound dog, cryin’ all the [I] time

Well, you ain’t [V] never caught a rabbit, and you [IV] ain’t no friend of [I] mine.

When they said you was [I] high classed, well that was just a lie.

When they said you was [IV] high classed, well that was just a [I] lie.

You ain’t [V] never caught a rabbit and you [IV] ain’t no friend of [I] mine.

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

This blues format is one example of what we might call musical form. It should be mentioned that the term “blues” is used somewhat loosely and is sometimes used to describe a tune with a “bluesy” sound, even though it may not follow the twelve-bar blues form. The blues is vitally important to American music because it influenced not only later jazz but also rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

AABA Form

Another important form to jazz and popular music is AABA form. Sometimes this is also called thirty-two-bar form; in this case, the form has thirty-two measures or bars, much like a twelve-bar blues has twelve measures or bars. This form was used widely in songs written for Tin Pan Alley, Vaudeville, and musicals from the 1910s through the 1950s. Many so-called jazz standards spring from that repertoire. Interestingly, these popular songs generally had an opening verse and then a chorus. The chorus was a section of thirty-two-bar form and often the part that audiences remembered. Thus, the chorus was what jazz artists took as the basis of their improvisations.

Video 2.15: “(Somewhere) Over the Rainbow,” as sung by Judy Garland in 1939 (accompanied by Victor Young and His Orchestra), is a well-known tune that is in thirty-two-bar form.

After an introduction of four bars, Garland enters with the opening line of the text, sung to melody A. “Somewhere over the rainbow way up high, there’s a land that I heard of once in a lullaby.” This opening line and melody lasts for eight bars. The next line of the text is sung to the same melody (still eight bars long) as the first line of text. “Somewhere over the rainbow skies are blue, and the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.” The third part of the text is contrasting in character. Where the first two lines began with the word “somewhere,” the third line begins with “someday.” Where the first two lines spoke of a faraway place, the third line focuses on what will happen to the singer. “Someday I’ll wish upon a star, and wake up where the clouds are far, behind me. Where troubles melt like lemon drops, away above the chimney tops, that’s where you’ll find me.” It is sung to a contrasting melody B and is eight bars long. This B section is also sometimes called the “bridge” of a song. The opening melody returns for a final time, with words that begin by addressing that faraway place dreamed about in the first two A sections and that end in a more personal way, similar to the sentiments in the B section. “Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly. Birds fly over the rainbow. Why then, oh why can’t I?” This section is also eight bars long, adding up to a total of thirty-two bars for the AABA form.

Although we’ve heard the entire thirty-two-bar form, the song is not over. The arranger added a conclusion to the form that consists of one statement of the A section, played by the orchestra (note the prominent clarinet solo); another re-statement of the A section, this time with the words from the final statement of the A section the first time; and four bars from the B section or bridge: “If happy little bluebirds…Oh why can’t I.” This is a good example of one way in which musicians have taken a standard form and varied it slightly to provide interest. Now listen to the entire recording one more time, seeing if you can keep up with the form.

Verse and Chorus Forms

Most popular music features a mix of verses and choruses. A chorus is normally a set of lyrics that recur to the same music within a given song. A chorus is sometimes called a refrain. A verse is a set of lyrics that are generally, although not always, just heard once over the course of a song.

In a simple verse-chorus form, the same music is used for the chorus and for each verse. “Can the Circle Be Unbroken” (1935) is a good example of a simple verse-chorus form. Many childhood songs and holiday songs also use a simple verse-chorus song.

Video 2.16: Can the Circle Be Unbroken—The Carter Family

In a simple verse form, there are no choruses. Instead, there is a series of verses, each sung to the same music. Hank Williams’s “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” (1949) below is one example of a simple verse form. After Williams sings two verses, each sixteen bars long, there is an instrumental verse, played by guitar. Williams sings a third verse followed by another instrumental verse, this time also played by guitar.

Video 2.17: Hank Williams Sr., “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”

Composition and Improvisation

Music from every culture is made up of some combination of the musical elements. Those elements may be combined using one of two major processes: composition and improvisation.

Composition is the process whereby a musician notates musical ideas using a system of symbols or using some other form of recording. We call musicians who use this process “composers.” When composers preserve their musical ideas using notation or some form of recording, they intend for their music to be reproduced the same way every time.

Improvisation is a different process. It is the process whereby musicians create music spontaneously using the elements of music. Improvisation still requires the musician to follow a set of rules. Often the set of rules has to do with the scale to be used, the rhythm to be used, or other musical requirements using the musical elements.

Listen to the example of Louis Armstrong below. Armstrong is performing a style of early New Orleans jazz in which the entire group improvises to varying degrees over a set musical form and melody. The piece starts out with a statement of the original melody by the trumpet, with Armstrong varying the rhythm of the original written melody as well as adding melodic embellishments. At the same time, the trombone improvises supporting notes that outline the harmony of the song, and the clarinet improvises a completely new melody designed to complement the main melody of the trumpet. The rhythm section of piano, bass, and drums is improvising their accompaniment underneath the horn players but is doing so within the strict chord progression of the song. The overall effect is one in which you hear the individual expressions of each player but can still clearly recognize the song over which they are improvising. This is followed by Armstrong interpreting the melody. Next, we hear individual solos improvised on the clarinet, the trombone, and the trumpet. The piece ends when Armstrong sings the melody one last time.

Video 2.18: Louis Armstrong, “When the Saints Go Marching In,” 1961

Composition and Improvisation Combined

In much of the popular music we hear today, like jazz and rock, both improvisation and composition are combined.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we learned a basic definition of music as well as definitions of the basic elements of music. We also explored some basic facts about acoustics, including the nature of sound. We learned how tones composed of organized sound waves sound to us like definite pitches, while disorganized sound waves are perceived as noise. We briefly touched on the harmonic series and how it influenced the nature of music, including properties of sound such as timbre.

Next, we explored how the development of musical notation made it possible to organize sounds into a wide variety of configurations. There are an infinite number of possible performing forces, but the most common would have to be the human voice followed by a wide variety of instruments, including strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion, keyboards, and electric instruments.

Next, we discussed the four main components of music: melody, harmony, rhythm, and texture. Melody is defined primarily by its shape and can be broken up into smaller components called motives. Harmony, which is the vertical aspect of music, can be described in its most basic terms as dissonant or consonant. Harmony is often built in thirds through the use of three-note chords called triads or four-note chords called seventh chords. Whole sequences of chords are known as chord progressions. Compositions are harmonically grounded through the use of key centers, tonic notes, and scales.

Rhythm is the way the music is organized in respect to time. The fundamental unit of time is the beat, which is further broken into groupings called measures. These groupings are determined by the meter of the piece, which is often either duple, triple, or quadruple. The speed at which these beats go by is known as the tempo. Other rhythmic devices such as syncopation and polyrhythm can add further variety to the music. On a larger scale, music is put together in terms of its form. We discussed three common song forms: the blues, AABA, and the Verse and Chorus.

Texture refers to the ways in which musical lines of a musical piece interact. Common textures include monophonic texture (one melodic line), homophonic texture (accompanied by chords), and polyphonic texture (simultaneous melodies). We also saw that composition and improvisation are the two major processes used to combine the musical elements we discussed. They may be used independently, or they may be combined within a composition.

Test Your Understanding

a disorganized sound with no observable pitch

the distance between two musical pitches where the higher pitch vibrates exactly twice as many times per second as the lower

the distance between adjacent notes in a musical scale

the variation in the volume of musical sound (the amplitude of the sound waves)

refers to how high the wave form appears to vibrate above zero when seen on an oscilloscope; louder sounds create higher oscilloscope amplitude readings

The support underlying a melody. For instance, in a typical show tune, the singer performs the melody, while the band provides the accompaniment.

text set to a melody written in monophonic texture with un-notated rhythms typically used in religious worship

Whether the basic pattern is played right side up or upside down

the way in which the beats are grouped together in a piece

the speed at which the beat is played

the low, medium, and high sections of an instrument or vocal range

the tone color or tone quality of a sound

the way the music is organized in respect to time

the ways in which musical lines of a musical piece interact

the study of how sound behaves in physical spaces

the instruments comprising a musical group (including the human voice). Also known as instrumentation.