15 Louisiana Music and Culture

Edited by Bonnie Le

Learning Objectives

- Describe a brief history of the Acadians in Southern Louisiana.

- Identify the different instruments used in Cajun music.

- Describe how the style of Cajun music was developed and performed.

- Describe the roles music and dance play in reproducing Cajun culture and community.

- Identify prominent Cajun musicians and songwriters.

- Describe a brief history of Zydeco music.

- Identify selected current Zydeco musicians.

Timeline of Acadian and Cajun History and Music

Cajuns

Adapted from “Cajuns,” Wikipedia, 2022, License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Who Are the Cajuns?

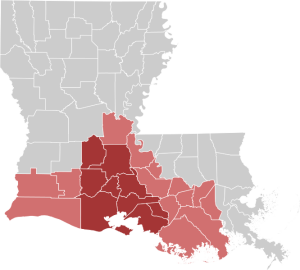

The Cajuns (keɪdʒənz), also known as Louisiana Acadians (French: les Acadiens), are an ethnic group mainly living in the U.S. state of Louisiana. While Cajuns are usually described as the descendants of the Acadian exiles, Louisianans frequently use Cajun as a broad cultural term (particularly when referencing Acadiana). Although Cajun and Creole today are often portrayed as separate identities, Louisianans of Cajun descent were historically considered to be Louisiana Creoles. Cajuns make up a significant portion of south Louisiana’s population and have had an enormous impact on the state’s culture.

While Lower Louisiana had been settled by French colonists since the late 17th century, many Cajuns trace their roots to the influx of Acadian settlers after the Great Expulsion from their homeland during the French and British hostilities prior to the Seven Years’ War (1756 to 1763). The Acadia region to which modern Cajuns trace their origin consisted largely of what are now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island plus parts of eastern Quebec and northern Maine. Since their establishment in Louisiana, the Cajuns have become famous for their French dialect, Louisiana French (also called “Cajun French”), and have developed a vibrant culture including folkways, music, and cuisine. The Acadiana region is heavily associated with them.

History of Acadian Ancestors

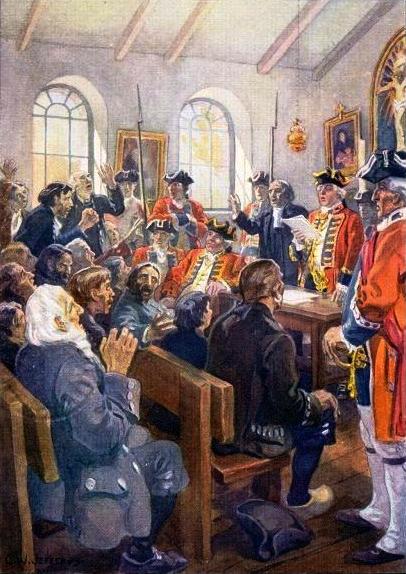

The British conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next 45 years, the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to the Crown. During this period, Acadians participated in various military operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour. During the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years’ War and known by that name in Canada and Europe), the British sought to neutralize the Acadian military threat and to interrupt their vital supply lines to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia (see figure 15.2). The territory of Acadia was afterward divided and apportioned to various British colonies, now Canadian provinces: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and the Gaspe Peninsula in the province of Quebec. The deportation of the Acadians from these areas beginning in 1755 has become known as the Great Upheaval or Le Grand Dérangement.

The Acadians’ migration from Canada was spurred by the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the war. The treaty terms provided 18 months for unrestrained emigration. Many Acadians moved to the region of the Atakapa in present-day Louisiana, often traveling via the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Joseph Broussard led the first group of 200 Acadians to arrive in Louisiana on February 27, 1765, aboard the Santo Domingo (see figure 15.3). On April 8, 1765, he was appointed militia captain and commander of the “Acadians of the Atakapas” region in St. Martinville.

Some of the settlers wrote to their family scattered around the Atlantic to encourage them to join them at New Orleans. For example, Jean-Baptiste Semer wrote to his father in France:

My dear father . . . you can come here boldly with my dear mother and all the other Acadian families. They will always be better off than in France. There are neither duties nor taxes to pay and the more one works, the more one earns without doing harm to anyone.

— Jean-Baptiste Semer, 1766

The Acadians were scattered throughout the eastern seaboard. Families were split and boarded ships with different destinations. Many ended up west of the Mississippi River in what was then French-colonized Louisiana, including territory as far north as Dakota territory. France had ceded the colony to Spain in 1762, prior to their defeat by Britain and two years before the first Acadians began settling in Louisiana. The interim French officials provided land and supplies to the new settlers. The Spanish governor, Bernardo de Gálvez, later proved to be hospitable, permitting the Acadians to continue to speak their language, practice their native religion (Roman Catholicism, which was also the official religion of Spain), and otherwise pursue their livelihoods with minimal interference. Some families and individuals did travel north through the Louisiana territory to set up homes as far north as Wisconsin. Acadians fought in the American Revolution. Although they fought for Spanish General Galvez, their contribution to the winning of the war has been recognized.

Galvez left New Orleans with an army of Spanish regulars and the Louisiana militia made up of 600 Acadian volunteers and captured the British strongholds of Fort Bute at Bayou Manchac, across from the Acadian settlement at St. Gabriel. On September 7, 1779, Galvez attacked Fort Bute and then on September 21, 1779, attacked and captured Baton Rouge.

The Spanish colonial government settled the earliest group of Acadian exiles west of New Orleans in what is now south-central Louisiana—an area known at the time as Attakapas and later the center of the Acadiana region. As Brasseaux wrote, “The oldest of the pioneer communities . . . Fausse Point, was established near present-day Loreauville by late June 1765.” The Acadians shared the swamps, bayous, and prairies with the Attakapa and Chitimacha Native American tribes.

After the end of the American Revolutionary War, about 1,500 more Acadians arrived in New Orleans. About 3,000 Acadians had been deported to France during the Great Upheaval. In 1785, about 1,500 were authorized to immigrate to Louisiana, often to be reunited with their families or because they could not settle in France. Living in a relatively isolated region until the early 20th century, Cajuns today are largely assimilated into mainstream society and culture. Some Cajuns live in communities outside Louisiana. Also, some people identify themselves as Cajun culturally despite lacking Acadian ancestry.

Cajun Music

By Joshua Caffery, 64 Parishes, (c) 2020. Text used with permission.

Cajun music is an accordion- and fiddle-based largely francophone folk music originating in southwestern Louisiana. Most people identify Cajun music with Louisiana’s Acadian settlers and their descendants, the Cajuns, but this music in fact refers to an indigenous mixture with complex roots in Irish, African, German, Appalachian as well as Acadian traditions. As distinct from zydeco music, Cajun music is most often performed by white musicians. While zydeco tends to incorporate elements of rhythm and blues, blues, and more recently hip-hop and rap, Cajun music has historically been influenced by Western swing, rock ’n’ roll, and country music. Although the historical and cultural center of Cajun music continues to be southwestern Louisiana, interest in the music has spread in recent decades, and practitioners and fans of Cajun music can be found today throughout the world.

Something to Think About

While zydeco tends to incorporate elements of rhythm and blues, blues, and more recently hip-hop and rap, Cajun music has historically been influenced by Western swing, rock ’n’ roll, and country music. What are the similarities of zydeco and Cajun music? How are the two styles of music influenced by their customs and culture?

Instrumentation

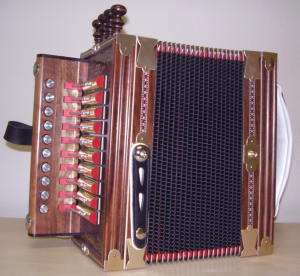

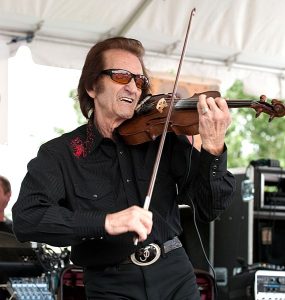

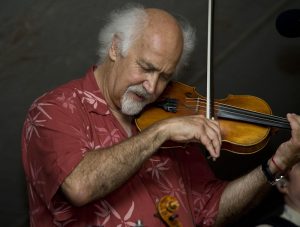

Cajun music is marked by its exclusive use of the diatonic accordion (zydeco musicians, in contrast, use either the triple-row, chromatic, or diatonic accordion). Resilient folk instruments that may have been brought to Louisiana by German settlers—though the earliest documentary evidence finds them in the hands of African American musicians—diatonic accordions are button accordions that feature a fairly limited melodic range. Most diatonic accordions played by Cajun musicians are tuned to either C or D major scales. Accordions are the loudest instrument in Cajun music and often begin and end any particular song (see figure 15.5). Along with the diatonic accordion, the fiddle is the instrument most central to Cajun music. Although a variety of tunings may be employed, Cajun musicians normally play in standard violin tuning (GDAE) or “tuned-down,” one whole-step below standard tuning (see figure 15.6).

A typical modern Cajun band, performing for a public dance, includes accordion, fiddle, guitar, bass, and drums. Other instruments, including the pedal steel guitar and the triangle (or ’tit fer), are also common. Many early recordings of Cajun music feature a trio of accordion, fiddle, and acoustic guitar or simply accordion and fiddle. In addition, a distinct twin-fiddling style associated with Cajun music exists, in which one fiddler plays a melody while the other provides rhythmic accompaniment, or “seconding.” In most instances, accordion and fiddle provide melody (together or separately) while the rest of the band acts as a rhythm section. Steel and six-string guitars, however, also may be used as melody instruments (see figure 15.7).

Style

In a public dance setting, most Cajun songs can be described as two-steps or waltzes, in accordance with the tradition’s most common dance steps. Two-steps are faster songs in a 2/4 time signature, while waltzes are slower songs, in 3/4 time. In Cajun music, a “blues” normally refers to a slower song in 2/4 time, which may or may not conform to a standard 12-bar blues formula. Cajun two-steps, in addition, may be played with a “swing” feel, reflecting the historical influence of Western swing on the Cajun genre.

Video 15.1: How to Dance the Cajun Two-Step

Video 15.2: Cajun Two-Step Performance by Jubilee American Dance Theatre, part of a Cajun Suite of dances, 2005

Both early recordings and field recordings made by folklorists in the homes of Cajun musicians throughout the twentieth century point to a broader array of song types than those found in public dance performance—an older tradition related to, but distinct from, the indigenous accordion and fiddle-based styles. A cappella ballads, some dating back hundreds of years, have persisted into the twentieth century, primarily in the private, domestic repertoire of female singers. Other song styles with roots in European folk music and dance, such as the mazurka, the hornpipe, and the reel, are evident in early recordings, though they have largely disappeared from modern Cajun music.

Songs

The contemporary Cajun music repertoire includes hundreds of traditional songs and an ever-expanding list of newer material. Although many authors of the songs that form the core repertoire have been lost to time, commercial recordings have helped preserve credits for many twentieth-century songs. Prominent songwriters, including D. L. Menard, Marc Savoy, Adam Hebert, and Ivy Dugas, have succeeded in writing new songs in a traditional vein. Although the fluency in southwestern Louisiana’s vernacular French continues to decline with the demise of native speakers, young songwriters continue to compose in French and add original songs to the repertoire.

Over time, a small number of Cajun songs have become “hits,” reaching audiences outside the local Cajun population and crossing over into mainstream popular culture. Most famously, the song “Jolie Blonde,” first popularized in the 1946 recording by Cajun swing fiddler Harry Choates and by numerous artists afterward, became a nationwide hit. In addition, a number of songs qualify as regional hits, including Jimmy C. Newman’s “Lâche pas la Patate” and D. L. Menard’s “La Porte d’en Arriére.” As these hits have faded from broader popularity, they have been retained as part of the traditional repertoire.

A Brief Chronology

Although Cajun music has remained dynamic over time, certain trends and currents are evident in commercial recordings, the first of which were made in the late 1920s. These first recordings have come to embody a “classic” period in the music, largely because they were the first recordings of the music widely available. “Lafayette” by Cléoma and Joe Falcon, as well as the duos of fiddler Dennis McGee with both Creole accordionist Amédé Ardoin and fiddler Sady Courville, form the core of the early “classic” acoustic sound. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Cajun accordion temporarily faded in prominence, largely because of the craze for fiddle-based, more melodically complex Western swing.

After World War II, interest in the accordion reignited with the powerful playing and singing of Iry LeJeune. The 1950s saw the rise of figures such as songwriter/accordionist Lawrence Walker, who managed to accommodate the accordion to a smoother style reminiscent of the swing era, but owing more to the influence of country and honky-tonk sounds. In the 1960s, Aldus Roger and the Lafayette Playboys helped to merge the driving accordion style of LeJeune with the smoother sensibilities of Walker, even as the Balfa Brothers, in step with the nationwide folk boom, found widespread acclaim with a more acoustic, folksy sound. Some musicians, such as D. L. Menard, ran the gamut of stylistic possibilities, playing in acoustic settings while also performing with a full band in the Cajun/honky-tonk style that earned him the moniker “The Cajun Hank Williams.”

Beginning with the triumphant performance of Dewey Balfa, Louis Lejeune, and Gladdy Thibodeaux at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, Cajun musicians increasingly began traveling and performing abroad, typically via the emerging folk festival circuit. As a result of the music’s broadening recognition, young revivalists of the 1970s and 1980s, such as Zachary Richard, Michael Doucet and Beausoleil, and Cajun/rock sensation Wayne Toups, established successful professional careers that persist to this day. During the same period and into the 1990s, husband-and-wife duo Marc and Ann Savoy cultivated a barebones acoustic approach to the music, while Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys explored both traditional and progressive sounds.

While all of the different styles discussed above persist in one way or another today, the late 1990s and early twenty-first century can be characterized as a neotraditional phase, in which many of the most popular groups scoured past recordings for inspiration. Bands such as the Red Stick Ramblers and the Lost Bayou Ramblers hearkened back to the experimentations of the early swing era, while Balfa Toujours (led by Dewey Balfa’s daughter, Christine) and the Pine Leaf Boys perpetuated both the twin-fiddling style of the Balfa Brothers as well as the dancehall styles of earlier decades.

In general, contemporary Cajun music features a dynamic range of styles, drawn both from the local tradition and from other genres of American music. Live Cajun music may be heard throughout southwestern Louisiana at dance halls like La Poussière in Breaux Bridge and Randol’s Restaurant in Lafayette, as well as at local festivals like the annual Festivals Acadien et Créole or the Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival.

Major Cajun Musicians

Marc Savoy

Adapted from “Marc Savoy,” Wikipedia, 2022, CC BY-SA 3.0

Marc Savoy (sah-vwah), born October 1, 1940, is an American musician and builder and player of the Cajun accordion. Born on his grandfather’s rice farm near Eunice, Louisiana, his grandfather was a fiddler who occasionally played with the legendary Dennis McGee, who was once a tenant farmer on his grandfather’s property. Marc Savoy began playing traditional music when he was 12 years old. Savoy holds a degree in chemical engineering, but his primary income is derived from his accordion-making business based at his Savoy Music Center in Eunice. His wife is a singer and guitarist, and they often perform together; see Marc Savoy on accordion, Ann Savoy on guitar, and others pictured below, figure 15.8.

Video 15.3: One of Marc Savoy’s songs is “Under the Green Oak Tree,” written in 1976 with Dewey Balfa and D. L. Menard.

Dewey Balfa

Adapted from “Dewey Balfa,” Wikipedia, 2021, CC BY-SA 3.0

Dewey Balfa (1927-1992) was an American Cajun fiddler and singer who contributed significantly to the popularity of Cajun music. Balfa was born near Mamou, Louisiana, and is best known for his 1964 performance at the Newport Folk Festival with Gladius Thibodeaux and Vinus Lejeune, where the group received an enthusiastic response from over seventeen thousand audience members. He sang the song “Parlez Nous a Boire” in the 1981 cult film Southern Comfort in which he had a small role.

Video 15.4: Parlez-nous a boire—Balfa brothers Marc Savoy, scene from Southern Comfort

Dewey Balfa was born in Grand Louis, Louisiana, a small community west of Mamou. He was the son of Amay (née Ardoin) and Charles Balfa, who were sharecroppers. Balfa had learned most of his songs from his grandmother and his father, who was a fiddle player.

In 1965, he formed the Balfa Brothers after the enthusiastic response from the performance at the Newport Folk Festival. This led to their first LP, produced by Swallow Records.

Balfa appears in a documentary film entitled Les Blues de Balfa, produced by Yasha Aginsky. In one scene, Balfa is shown with Nathan Abshire entertaining a group of school children. Balfa gives a short lecture concerning the origins of Cajun music:

We are here to tell you a little bit about what a Cajun is. A Cajun is a person who his homeland was France. Went into Nova Scotia, at the time Acadia, and settled there and was there for about a hundred years, and afterwards the British took over the territory and then the French-speaking people, the French descendants, known as the Acadians, came down to the South-Western part of Louisiana, and that was back in 1755. So over all of these years, your language, and your music has been preserved from daddy to son or daddy to daughter or momma to daughter.

Video 15.5: Dewey Balfa and Robert Jardell, “Calcasieu Waltz,” 1983, shot by Alan Lomax and crew in Scott, Louisiana

BeauSoleil avec Michael Doucet

By Roger Hahn, 64 Parishes, 2019. Text used with permission

Formed during the Cajun revival of the 1970s, BeauSoleil and its founder, fiddler Michael Doucet, are among Louisiana’s most prominent ambassadors of Cajun music and culture. The band is particularly known and respected for emphasizing a wide range of Cajun musical traditions. Never content to re-create precise historical renderings of traditional Cajun music, BeauSoleil highlights the music’s inherent adaptability by incorporating elements of zydeco, blues, swamp pop, traditional New Orleans jazz, calypso, country, western swing, and rock and roll. Having recorded more than two dozen albums, BeauSoleil has received eleven nominations and two Grammy awards.

Origins and Influences

The origins of BeauSoleil lie in the experiences of its founder, Michael Doucet. Born in Lafayette Parish on February 14, 1951, he is the son of Louis Pierre Doucet and Mary Frances Leblanc Doucet. Raised in an extended family full of amateur and professional musicians, Doucet began playing banjo at age six and guitar at age eight. His uncle Will Knight played Cajun fiddle, banjo, and bass and was particularly influential. His grandmother learned about the family’s Acadian and French roots while serving as a nurse in France during World War I (1914–1918), and his mother was an avid student of the French oral tradition of storytelling. As a teen, Doucet and his cousin Zachary Richard formed a contemporary folk-rock band, the Bayou Drifters. In 1974, a music promoter hired the band to play at a folk music festival in France, sparking Doucet’s interest in the origins of Cajun music.

On his return to Louisiana, Doucet threw himself into an investigation of Cajun traditions and explored ways of translating them for contemporary audiences. With a 1975 Folk Arts Apprenticeship grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), he set about meeting and learning from as many traditional Cajun musicians as he could. Dewey Balfa, Sady Courville, Varise Connor, Freeman Fontenot, Luderin Darbone, Hector Duhon, Doc Guidry, Bébé Carriere, Lionel LeLeux, and Dennis McGee were among those he studied. At the same time, he helped form Coteau, a folk-rock band that played a traditional French Cajun repertoire while utilizing twin electric lead guitars. The group became popular enough along the Louisiana Gulf Coast to attract increasingly larger young audiences and, as a result, began to reenergize the local music scene.

As a side project, in 1975 Doucet formed a small acoustic ensemble dedicated strictly to the performance of traditional Cajun music. He named this endeavor BeauSoleil in an apparent double entendre. Although BeauSoleil translates as “beautiful sun,” it was also a nickname for Joseph Broussard, a legendary leader of the Acadian resistance movement in mid-eighteenth-century Canada. For Doucet, this covert allusion had a personal significance as well, since his mother’s side of the family included generations of Broussards.

Frustrated by their inability to negotiate a major recording contract, the members of Coteau parted ways in the late 1970s, and BeauSoleil became Doucet’s primary musical focus. In addition to Doucet, the band included David Doucet (Michael’s brother) on guitar and vocals, Jimmy Breaux on accordion, Mitchell Reed on fiddle and bass, Tommy Alesi on drums, and Billy Ware on percussion. In 1977, the band recorded its first album, The Spirit of Cajun Music, on Swallow Records. The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll described it as “an eclectic mix of blues, ballads, standards, and traditional music.”

Musical Style

The band’s unique combination of musical innovation and tradition reflected Doucet’s own instincts and previous experiences. His apprenticeships with Dennis McGee, a Cajun fiddler heavily influenced by French musical traditions, and Canray Fontenot, a Creole musician who incorporated elements of Afro-Caribbean culture, proved particularly influential. For Doucet, musical traditions were dynamic rather than static; he understood that folk music had absorbed multiple influences over centuries and believed it must continue to do so in order to remain alive and relevant. “Everything I play I learned from Louisiana,” he told Fiddler Magazine interviewer Niles Hokkanen. “I went back in time—not only to French music, but to blues, jazz, popular music, Irish music, whatever was there. As more old records are brought to light, you can see those influences and what a hotbed Louisiana was … so, my influences are the spectrum of Louisiana music.”

A confluence of events in the mid-1980s brought BeauSoleil’s innovative traditionalism to the world’s attention. First, tracks from the band were included in two movie soundtracks: Belizaire the Cajun (1986) and The Big Easy (1987). In addition, BeauSoleil became regular guests on the National Public Radio variety show Prairie Home Companion. Finally, in 1986, the band signed a deal with Rounder Records, assuring them national distribution and greater mainstream exposure. Between 1987 and 1997, the band released a dozen albums, and in 1988, they appeared as guest artists on Talk Is Cheap, a solo effort by Rolling Stones lead guitarist Keith Richards. Two years later, country-folk artist Mary Chapin Carpenter made reference to the band in her song “Down at the Twist and Shout,” which rose to number two on Billboard magazine’s country-music sales charts.

National recognition became a powerful catalyst for experimentation. BeauSoleil’s 1987 Rounder release, Bayou Boogie, featured guest artist Sonny Landreth, a southwestern Louisiana native who had developed an electric guitar style that seamlessly combined fingered chords with slide guitar effects. The band’s 1989 follow-up, Bayou Cadillac, featured zydeco, traditional Cajun, blues, traditional New Orleans jazz, and calypso, as well as original compositions and a medley that combined Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” the Bo Diddley anthem “Bo Diddley,” and the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian-inspired “Iko Iko.” Rolling Stone critic Steven Pond described the album as “world music, south-Louisiana style,” and over the next twenty years, BeauSoleil would release a half-dozen top twenty hits on Billboard’s World Music Album sales chart.

Video 15.6: Michael Doucet and BeauSoleil, “Courtableau”

The band’s studio output slowed considerably in the first decade of the twenty-first century, but BeauSoleil is still regarded as “an American institution,” as musician/music journalist James Christopher Monger observed in a review of their 2009 Grammy-nominated release, Alligator Purse. Numerous organizations have also honored Doucet’s contribution to traditional Cajun music. The NEA honored him with a National Heritage Fellowship in 2005. In addition, the United States Artists, a nonprofit organization formed in 2005 to encourage the careers of American artists through noncommercial financial support, awarded him a fellowship in 2007. In the eyes and ears of many, BeauSoleil remains a bellwether of Cajun excellence and a musical phenomenon that People magazine once described as “Louisiana’s hottest export since Tabasco Sauce.”

Zydeco

Adapted from “Zydeco,” Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

Zydeco (/ˈzaɪdɪˌkoʊ/ ZY-dih–koh or /ˈzaɪdiˌkoʊ/ ZY-dee-koh, French: Zarico) is a music genre that evolved in southwest Louisiana by French Creole speakers that blends blues, rhythm and blues, and music indigenous to the Louisiana Creoles and the Native American people of Louisiana. Although it is distinct in origin from the Cajun music of Louisiana, the two forms influenced each other, forming a complex of genres native to the region.

Characteristics

Zydeco music is typically played in an up-tempo, syncopated manner with a strong rhythmic core and often incorporates elements of blues, rock and roll, soul music, R&B, Afro-Caribbean, Cajun, and early Creole music. Zydeco music is centered around the accordion, which leads the rest of the band, and a specialized washboard, called a vest frottoir, as a prominent percussive instrument. Other common instruments in zydeco are the electric guitar, bass, keyboard, and drum set. If there are accompanying lyrics, they are typically sung in English or French. Many zydeco performers create original zydeco compositions, though it is also common for musicians to adapt blues standards, R&B hits, and traditional Cajun tunes into the zydeco style.

Video 15.7: C.J. Chenier & The Red Hot Louisiana Band—Man Smart, Woman Smarter

Zydeco Musicians

Young zydeco musicians such as C. J. Chenier (son of Clifton Chenier), Chubby Carrier, Geno Delafose, Terrance Simien, Nathan Williams, and others began touring internationally during the 1980s. Beau Jocque was a monumental songwriter and innovator who infused zydeco with powerful beats and bass lines in the 1990s, adding striking production and elements of funk, hip-hop, and rap. Young performers like Chris Ardoin, Keith Frank, and Zydeco Force added further by tying the sound to the bass drum rhythm to accentuate or syncopate the backbeat even more. This style is sometimes called “double clutching.”

Hundreds of zydeco bands continue the music traditions across the U.S. and in Europe, Japan, the UK, and Australia. A precocious 7-year-old zydeco accordionist, Guyland Leday, was featured in an HBO documentary about music and young people.

In 2007, zydeco achieved a separate category in the Grammy awards, the Grammy Award for Best Zydeco or Cajun Music Album category. But in 2011, the Grammy awards eliminated the category and folded the genre into its new Best Regional Roots Album category. More recent zydeco artists include Lil’ Nate, Leon Chavis, Mo’ Mojo, and Kenne’ Wayne. Torchbearer Andre Thierry has kept the tradition alive on the West Coast. Leading the world of traditional zydeco today is Dwayne Dopsie (son of Rockin’ Dopsie) and his band, the Zydeco Hellraisers. They were nominated for best Regional Roots Album in the 2017 Grammy Awards.

Video 15.8: Dwayne Dopsie & The Hellraisers Live in Peer, Belgium—Where’d My Baby Go

While zydeco is a genre that has become synonymous with the cultural and musical identity of Louisiana and an important part of the musical landscape of the United States, this southern black music tradition has received wide recognition throughout the country. Because of the migration of the French-speaking blacks and multiracial Creoles, the mixing of Cajun and Creole musicians, and the warm embrace of people from outside these cultures, there are multiple hotbeds of zydeco: Louisiana, Texas, Oregon, California, and Europe as far north as Scandinavia. There are zydeco festivals throughout America and Europe.

Summary

This chapter looked briefly at the history of the Louisiana Acadians, an ethnic group mainly living in the U.S. state of Louisiana who became commonly known as “Cajuns” starting with the British conquest of Acadia in 1710 and the Acadians’ refusal to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to the Crown. This led to the Acadians being deported and eventually settling in Louisiana. We then looked at Cajun music, its instruments, and the style of dance associated with the music. A chronology of the music and the musicians was given. This chapter looked at various Cajun musicians and their music, such as Marc Savoy, an American musician, builder, and player of the Cajun accordion. The chapter then gave a brief history of Dewey Balfa, an American Cajun fiddler and singer who contributed significantly to the popularity of Cajun music. This chapter also explored the music of Michael Doucet, who came from a family full of amateur and professional musicians, and how he and his band Beausoleil influenced Cajun music. The chapter concluded with a brief history of zydeco music, its characteristics, and current zydeco musicians.

Suggested Readings

- Ancelet, Barry Jean. Cajun and Creole Music Makers: Musiciens cadiens et créoles. 2nd ed. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999.

- Ancelet, Barry Jean. “Cajun Music.” Journal of American Folklore 107, 424 (Spring 1994): 285–303.

- Brasseaux, Ryan A., and Kevin S. Fontenot, eds. Accordions, Fiddles, Two Step & Swing: A Cajun Music Reader. Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2006.

- Francois, Raymond E. Yé Yaille Chère: Traditional Cajun Dance Music. 1st ed. Ville Platte, LA: Swallow Publishing, 1990.

- Hokkanen, Niles. “Michael Doucet: Hot Cajun Fiddle.” In Fiddler Magazine’s Favorites, edited by Mary Larsen and Jack Tuttle. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay Publications, Inc., 1999.

- Koster, Rick. “Modern Cajun.” In Louisiana Music: A Journey from R&B to Zydeco, Jazz to Country, Blues to Gospel, Cajun Music to Swamp Pop to Carnival Music and Beyond, pp. 177–188. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002.

- Lichtenstein, Grace, and Danker, Laura. “Ragin’ Cajuns.” In Musical Gumbo: The Music of New Orleans, pp. 195–235. New York: W. W. Norton, 1993.

- Savoy, Ann A. Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People. Eunice, LA: Bluebird Press, 1984.

Suggested Listening

- Balfa, Dewey, Marc Savoy, and D. L. Menard. Under a Green Oak Tree. Audio CD. El Cerrito: Arhoolie Records, 1993.

- Beausoleil. The Best of Beausoleil. Audio CD. El Cerrito: Arhoolie Records, 1997.

- LeJeune, Iry. Cajun’s Greatest: The Definitive Collection. Audio CD. London: Ace Records, 2004.

- McGee, Dennis. Complete Early Recordings 1929–1930. Audio CD. Yazoo, 1994.

- Riley, Steve, and the Mamou Playboys. Best of Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys. Audio CD. Rounder / Umgd, 2008.