10 Music of the Romantic Period and 19th Century

Learning Objectives

- Describe the historical and cultural contexts of nineteenth-century music, including musical Romanticism and nationalism.

- Identify selected genres of nineteenth-century music and their associated expressive aims, uses, and styles.

- Identify the music of selected composers of nineteenth-century music and their associated styles.

- Explain ways in which music and other cultural forms interact in nineteenth-century music in genres such as the art song, program music, opera, and musical nationalism.

Excerpts from Understanding Music

By Jeff Kluball and Elizabeth Kramer

Edited by Bonnie Le

Timeline

- 1801: Wordsworth publishes his Lyrical Ballades

- 1814-1815: Congress of Vienna, ending Napoleon’s conquest of Europe and Russia

- 1815: Schubert publishes The Erlking

- 1818: Mary Shelley publishes Frankenstein

- 1818: Caspar David Friedrich paints Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

- 1827: Beethoven dies

- 1829: Felix Mendelssohn leads a revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which leads to a revival of Bach’s music more generally

- 1830s: Eugène Delacroix captures revolutionary and nationalist fervor in his paintings

- 1830s: Clara Wieck and Franz Liszt tour (separately) as virtuoso pianists

- 1831: Fryderyk Chopin immigrates to Paris from the political turmoil in his native country of Poland

- 1832: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe dies

- 1840: Clara and Robert Schumann marry

- 1850s: Realism becomes prominent in art and literature

- 1853: Verdi composes La Traviata

- 1861-1865: Civil War in the U.S.

- 1870-71: Franco-Prussian War

- 1874: Bedřich Smetana composes The Moldau

- 1876: Johannes Brahms completes his First Symphony

- 1876: Wagner premiers The Ring of the Nibelungen at his Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, Germany

- 1882: Tchaikovsky writes the 1812 Overture

- 1891-1892: John Philip Sousa tours the U.S. leading the U.S. Marine Band

- 1892-1895: Antonín Dvořák visits the U.S., helps establish the first American music conservatory, and composes the New World Symphony

Introduction and Historical Context

This chapter considers music of the nineteenth century, a period often called the “Romantic era” in music. Romanticism might be defined as a cultural movement stressing emotion, imagination, and individuality. It started in literature around 1800 and then spread to art and music. By around 1850, the dominant aesthetic (artistic philosophy) of literature and visual art began to shift to what is now often called a time of realism (cultural expressions of what is perceived as common and contemporary). Cultural Nationalism (pride in one’s culture) and Exoticism (fascination with the other) also became more pronounced after 1850, as reflected in art, literature, and music. Realism, nationalism, and Exoticism were prominent in music as well, although we tend to treat them as sub-categories under a period of musical Romanticism that spanned the entire century.

The power and expression of emotion exalted by literary Romanticism were equally important for nineteenth-century music, which often explicitly attempted to represent every shade of human emotion, the most prominent of which are love and sorrow. Furthermore, the Romantics were very interested in the connections between music, literature, and the visual arts. Poets and philosophers rhapsodized about the power of music, and musicians composed both vocal and instrumental program music explicitly inspired by literature and visual art. In fact, for many nineteenth-century thinkers, music had risen to the top of the aesthetic hierarchy. Music was previously perceived as inferior to poetry and sculpture, as it had no words or form. In the nineteenth century, however, music was understood to express what words could not express, thus transcending the material for something more ideal and spiritual; some called this expression “absolute music.”

As we listen to nineteenth-century music, we might hear some similarities with music of the classical era, but there are also differences. Aesthetically speaking, classicism tends to emphasize balance, control, proportion, symmetry, and restraint. Romanticism seeks out the new, the curious, and the adventurous, emphasizing qualities of remoteness, boundlessness, and strangeness. It is characterized by restless longing and impulsive reaction, as well as freedom of expression and pursuit of the unattainable.

Geo-politically, the nineteenth century extends from the French Revolution to a decade or so before World War I. The French Revolution wound down around 1799, when the Napoleonic Wars then ensued. The Napoleonic Wars were waged by Napoléon Bonaparte, who had declared himself emperor of France. Another war was the United States Civil War from 1861 to 1865. The United States also saw expansion westward as the gold rush brought in daring settlers. Even though the United States was growing, England was currently the dominant world power. Its whaling trade kept ships sailing and lamps burning. Coal fueled the Industrial Revolution and the ever-expanding rail system. Economic and social power shifted increasingly towards the common people due to revolts. These political changes affected nineteenth-century music as composers began to aim their music at the more common people, rather than just the rich.

Political nationalism was on the rise in the nineteenth century. Early in the century, Bonaparte’s conquests spurred on this nationalism, inspiring Italians, Austrians, Germans, Eastern Europeans, and Russians to assert their cultural identities, even while enduring the political domination of the French. After France’s political power diminished with the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, politics throughout much of Europe were still punctuated by revolutions, first a minor revolution in 1848 in what is now Germany and then the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Later in the century, Eastern Europeans, in what is now the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and the Russians developed schools of national music in the face of Austro-German cultural, and sometimes political, hegemony. Nationalism was fed by the continued rise of the middle class as well as the rise of republicanism and democracy, which defines human beings as individuals with responsibilities and rights derived as much from the social contract as from family, class, or creed.

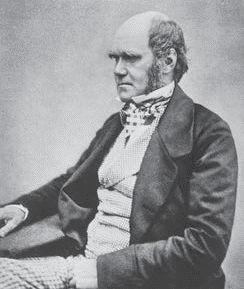

Romantics were fascinated by nature, and the middle-class public followed naturalists like Americans John James Audubon (1785-1851) and John Muir (1838-1914) and the Englishman Charles Darwin (1809-1882) as they observed and recorded life in the wild. Darwin’s evolutionary theories based on his voyages to locales such as the Galapagos Islands were avidly debated among the people of his day.

Visual Art

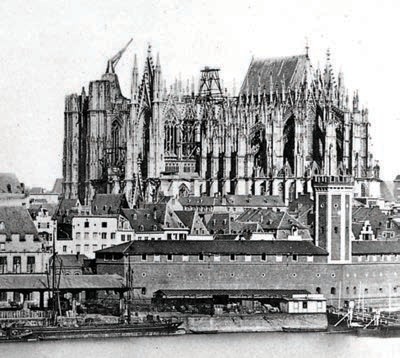

Romantics were fascinated by the imaginary, the grotesque, and by that which was chronologically or geographically foreign. Romantics were also intrigued by the Gothic style: a young Göethe raved about it after visiting the Gothic Cathedral in Strasbourg, France. His writings, in turn, spurred the completion of the Cathedral in Cologne, Germany, which had been started in the Gothic style in 1248 and then completed in that same style between the years 1842 and 1880 (Figure 10.3).

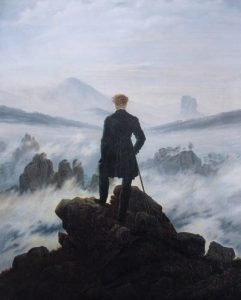

Romantic interest in the individual, nature, and the supernatural is also very evident in nineteenth-century landscapes, including those of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). One of his most famous paintings, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818; Figure 10.4), shows a lone man with his walking stick, surrounded by a vast horizon. The man has progressed to the top of a mountain, but there his vision is limited due to the fog. We do not see his face, perhaps suggesting the solitary reality of a human subject both separate from and somehow spiritually attuned to the natural and supernatural.

As the nineteenth century progressed, European artists became increasingly interested in what they called “realist” topics—that is, in depicting the lives of the average human as he or she went about living in the present moment. While the realism in such art is not devoid of idealizing forces, it does emphasize the validity of everyday life as a topic for art alongside the value of craft and technique in bringing such “realist” scenes to life.

Literature

The novel, which had emerged forcefully in the eighteenth century, became the literary genre of choice in the nineteenth century. Many German novels focused on a character’s development; most important of these novels are those by the German philosopher, poet, and playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who was fascinated with the supernatural and set the story of Faust. Faust is a man who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge, in an epic two-part drama. English author Mary Shelley (1797-1851) explored nature and the supernatural in the novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (1818), which examines current scientific discoveries as participating in the ancient quest to control nature. Later in the century, British author Charles Dickens exposed the plight of the common man during a time of Industrialization. In France, Victor Hugo (1802-1885) wrote on a broad range of themes, from what his age saw as the grotesque in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) to the topic of French Revolution in Les Misérables (1862). Another Frenchman, Gustav Flaubert, captured the psychological and emotional life of a “real” woman in Madame Bovary (1856). In the United States, Mark Twain created Tom Sawyer (1876).

Nineteenth-Century Musical Contexts

Music’s influence grew in the nineteenth century, becoming more prominent in the education of the still growing middle class; even in the United States, music education appeared in the public schools by the end of the century. Amateur music making in the home and in local civic groups was at its height. Piano music was a major component of private music making. The salons and soirées of upper-middle-class and aristocratic women drew many of these private musical performances.

More concerts in public venues enjoyed increased attendance; some of these concerts were solo recitals, and others featured large symphony orchestras, sometimes accompanied by choirs. Their performers were often trained in highly specialized music schools called conservatories, which took root in major European cities. By the end of the nineteenth century, traveling virtuoso performers and composers were some of the most famous personalities of their time. These musicians hailed from all over Europe.

Romantic aesthetics tended to conceptualize musicians as highly individualistic and often eccentric. Beethoven modeled these concepts and was the most influential figure of nineteenth-century music, even after his death in 1827. His perceived alienation from society, the respect he was given, and the belief in the transformative power of music that was often identified in his compositions galvanized Romantic perceptions. His music, popular in its own day, only became more popular after his death.

Music in the Nineteenth Century

Music Comparison Overview

| Classical Music | Nineteenth-Century Music |

|---|---|

| Mostly homophony, but with variation | Lyrical melodies, often with wider leaps |

| New genres such as the symphony and string quartet | Homophonic style still prevalent, but with variation |

| Use of crescendos and decrescendos | Larger performing forces using more diverse registers, dynamic ranges, and timbres |

| Question and answer (a.k.a. antecedent consequent) phrases that are shorter than earlier phrases | More rubato and tempo fluctuation within a composition |

| New emphasis on musical form: for example, sonata form, theme and variations, minuet and trio, rondo, and first-movement concerto form | More chromatic and dissonant harmonies with increasingly delayed resolutions |

| Greater use of contrasting dynamics, articulations, and tempos | Symphonies, string quartets, concertos, operas, and sonata-form movements continue to be written |

| Newly important miniature genres and forms such as the Lied and short piano composition | |

| Program music increasingly prominent | |

| Further development in performers’ virtuosity | |

| No more patronage system |

General Trends in Nineteenth-Century Music

Musical Style, Performing Forces, and Forms

The nineteenth century is marked by a great diversity in musical styles, from the conservative to the progressive. As identified by the style comparison chart above, nineteenth-century melodies continue to be tuneful and are perhaps even more songlike than classical-style melodies, although they may contain wider leaps. They still use sequences, which are often as a part of modulation from one key to another. Melodies use more chromatic (or “colorful”) pitches from outside the home key and scale of a composition.

Harmonies in nineteenth-century music are more dissonant than ever. These dissonances may be sustained for some time before resolving to a chord that is consonant. One composition may modulate between several keys, and these keys often have very different pitch contents. Such modulations tend to disorient the listening and add to the chaos of the musical selection. Composers were in effect “pushing the harmonic envelope.”

The lengths of nineteenth-century musical compositions ran from the minute to the monumental. Songs and short piano pieces were sometimes grouped together in cycles or collections. On the other hand, symphonies and operas grew. By the end of the century, a typical symphony might be an hour long, with the operas of Verdi, Wagner, and Puccini clocking in at several hours each. There is much nineteenth-century music for solo piano or solo voice with piano accompaniment. The piano achieved a modern form, with the full eighty-eight-note keyboard that is still used today and an iron frame that allowed for greater string tension and a wider range of dynamics.

During the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution facilitated and enabled marked improvements to many musical instruments besides the piano with its improved and updated iron frame and tempered metal strings. Efficient valves were added to the trumpet, and a general improvement in metal works tightened tolerances and metal fittings of all brass instruments. Along with the many improvements to instruments, new instruments were researched and created, including the piccolo, English horn, tuba, contrabassoon, and saxophone.

Orchestras also increased in size and became more diverse in makeup, thereby allowing composers to exploit even more divergent dynamics and timbres. With orchestral compositions requiring over 50 (and sometimes over 100) musicians, a conductor was important, and the first famous conductors date from this period. In fact, the nineteenth-century orchestra looked not unlike what you might see today at most concerts by most professional orchestras (see Figure 10.5). The wider nineteenth-century interest in emotion and in exploring connections between all the arts led to musical scores with more poetic or prose instructions from the composer. It also led to more program music, which as you will recall, is instrumental music that represents something “extra musical,” that is, something outside of music itself, such as nature, a literary text, or a painting. Extra musical influences, from the characteristic title to a narrative attached to a musical score, guided composers and listeners as they composed and heard musical forms.

Genres of Instrumental Music

Some nineteenth-century compositions use titles like those found in classical-style music, such as “Symphony No. 3,” “Concerto, Op. 3,” or “String Quartet in C Minor.” These compositions are sometimes referred to as examples of absolute music (that is, music for the sake of music). Program music with titles came in several forms. Short piano compositions were described as “character pieces” and took on names reflecting their emotional mood, state, or reference. Orchestral program music included the program symphony and the symphonic poem (also known as the tone poem). The program symphony was a multi-movement composition for orchestra that represented something extra musical, a composition such as Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique (discussed below). A symphonic or tone poem was a one-movement composition for orchestra, again with an extra musical referent, such as Bedřich Smetana’s Moldau.

Genres of Vocal Music

Opera continued to be popular in the nineteenth century and was dominated by Italian styles and form, much as it had been since the seventeenth century. Italian opera composer Giacomo Rossini even rivaled Beethoven in popularity. By the 1820s, however, other national schools were becoming more influential. Carl Maria von Weber’s German operas enhanced the role of the orchestra, whereas French grand opera by Meyerbeer and others was marked by the use of large choruses and elaborate sets. Later in the century, composers such as Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner would synthesize and transform opera into an even more dramatic genre.

Other large-scale choral works in the tradition of the Baroque cantata and oratorio were written for civic choirs, which would sometimes band together into larger choral ensembles in annual choral festivals. The song for voice and piano saw revived interest, and art songs were chief among the music performed in the home for private and group entertainment. The art song is a composition for solo voice and piano that merges poetic and musical concerns. It became one of the most popular genres of nineteenth-century Romanticism, a movement that was always looking for connections between the arts. Sometimes these art songs were grouped into larger collections called song cycles or, in German, Liederkreis. Among the important composers of early nineteenth-century German Lieder were Robert and Clara Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Franz Schubert.

Nineteenth-Century & Romantic-Era Composers

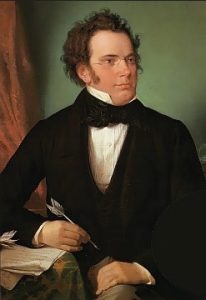

Music of Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Franz Schubert lived a short but prolific musical life. Like Joseph Haydn, he performed as a choirboy until his voice broke. He also received music lessons in violin, piano, organ, voice, and musical harmony: many of his teachers remarked on the young boy’s genius. Schubert followed in his father’s footsteps for several years, teaching school through his late teens, until he shifted his attention to music composition fulltime in 1818. By that time, he had already composed masterpieces for which he is still known, including the German Lied (art song), Der Erlkönig (in English, The Erlking), which we will discuss.

Schubert spent his entire life in Vienna in the shadow of the two most famous composers of his day: Ludwig van Beethoven, whose music we have already discussed, and Gioachino Rossini, whose Italian operas were particularly popular in Vienna in the first decade. Inspired by the music of Beethoven, Schubert wrote powerful symphonies and chamber music, which are still played today; his “Great” Symphony in C major is thought by many to be Schubert’s finest contribution to the genre. He wrote the symphony in 1825 and 1826, but it remained unpublished and indeed perhaps unperformed until Robert Schumann discovered it in 1838.

Schubert also wrote operas and church music. His greatest legacy, however, lies in his more than 600 Lieder, or art songs. Schubert was known as a master of the art song, or lied. His songs are notable for their beautiful melodies and clever use of piano accompaniment and bring together poetry and music in an exemplary fashion. Most are short, stand-alone pieces of one and a half to five minutes in length, but he also wrote a couple of song cycles. These songs were published and performed in many private homes and, along with all his compositions, provided so much entertainment in the private musical gatherings in Vienna that these events were renamed Schubertiades (see the famous depiction of one Schubertiade by the composer’s close friend Moritz Schwind, painted years after the fact from memory in 1868; Figure 10.7). Many of Schubert’s songs are about romantic love, a perennial song topic. Others, such as The Erlking, put to music Romantic responses to nature and to the supernatural. The Erlking is strikingly dramatic, a particular reminder that music and drama interacted in several nineteenth-century genres, even if their connections can be most fully developed in a lengthy composition, such as an opera.

Focus Composition: Schubert, The Erlking (1815)

Schubert set the words of several poets of his day, and The Erlking (1815) is drawn from the poetry of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The Erlking tells the story of a father who is rushing on horseback with his ailing son to the doctor. Delirious from fever, the son hears the voice of the Erlking, a grim reaper sort of king of the fairies who appears to young children when they are about to die, luring them into the world beyond. The father tries to reassure his son that his fear is imagined, but when the father and son reach the courtyard of the doctor’s house, the child is found to be dead.

As you listen to the song, follow along with its words. You may have to listen several times to hear the multiple connections between the music and the text. Are the ways in which you hear the music and text interacting beyond those pointed out in the listening guide?

Video 10.1: Erlkönig Schubert, Samuel Hasselhorn, Baritone

Listening Guide

- Composer: Franz Schubert

- Composition: The Erlkönig (in English, The Erlking)

- Date: 1815

- Genre: Art song

- Form: Through-composed

- Nature of text: In German

- Performing forces: Solo voice singing four roles (narrator, father, son and the Erlking) and piano

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is an art song that sets a poem for solo voice and piano.

- The poem tells the story of three characters, who are depicted in the music through changes in melody, harmony, and range.

- The piano sets the general mood and supports the singer by depicting images from the text.

- Other things to listen for:

- Piano accompaniment at the beginning that outlines a minor scale (perhaps the wind)

- Repeated fast triplet pattern in the piano, suggesting urgency and the running horse

- Shifts of the melody line from high to low range, depending on the character “speaking”

- Change of key from minor to major when the Erlking sings

- The slowing note values at the end of the song and the very dissonant chord

Music of the Mendelssohns

In terms of musical craft, few nineteenth-century composers were more accomplished than Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847). Growing up in an artistically rich, upper-middle-class household in Berlin, Germany, Felix Mendelssohn received a fine private education in the arts and sciences and proved himself to be precociously talented from a very young age. He would go on to write chamber music for piano and strings, art songs, church music, four symphonies, and oratorios as well as conduct many of Beethoven’s works as principal director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. All his music emulates the motivic and organic styles of Beethoven’s compositions, from his chamber music to his more monumental compositions. Felix was also well versed in the musical styles of Mozart, Handel, and Bach.

Felix descended from a family of prominent Jewish intellectuals; his grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was one of the leaders of the eighteenth-century German Enlightenment. His parents, however, seeking to break from this religious tradition, had their children baptized as Reformed Christians in 1816. Anti-Semitism was a fact of life in nineteenth-century Germany, and such a baptism opened some, if not all, doors for the family. Most agree that in 1832, the failure of Felix’s application for the position as head of the Berlin Singakademie was partly due to his Jewish ethnicity. This failure was a blow to the young musician, who had performed frequently with this civic choral society, most importantly in 1829, when he had led a revival of the St. Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach. Although today we think of Bach as a pivotal figure of the Baroque period, his music went through a period of neglect until this revival.

Initially, Felix’s father was reluctant to see his son become a professional musician; like many upper-middle-class businessmen, he would have preferred that his son enjoy music as an amateur. Felix, however, was both determined and talented and eventually secured employment as a choral and orchestral conductor, first in Düsseldorf and then in Leipzig, Germany, where he lived from 1835 until his death. In Leipzig, Felix conducted the orchestra and founded the town’s first music conservatory.

Focus Composition: Mendelssohn, Excerpts from Elijah (1846)

One of his last works, his oratorio Elijah, was commissioned by the Birmingham Festival in Birmingham, England. The Birmingham Festival was one of many nineteenth-century choral festivals that provided opportunities for amateur and professional musicians to gather once a year to make music together. Mendelssohn’s music was very popular in England, and the Birmingham Festival had already performed another Mendelssohn oratorio in the 1830s, giving the premier of Elijah in English in 1846.

Elijah is interesting because it is an example of music composed for middle-class music making. The chorus of singers was expected to be largely made up of musical amateurs, with professional singers brought in to sing the solos. The topic of the oratorio, the Hebrew prophet Elijah, is interesting as a figure significant to both the Jewish and Christian traditions, both of which Felix embraced to a certain extent. This composition shows Felix’s indebtedness to both Baroque composers Bach and Handel, while at the same time it uses more nineteenth-century harmonies and textures.

The following excerpt is from the first part of the oratorio and sets the dramatic story of Elijah calling the followers of the pagan god Baal to light a sacrifice on fire. Baal fails his devotees; Elijah then summons the God of Abraham to a display of power with great success. The excerpt here involves a baritone soloist who sings the role of Elijah and the chorus that provides commentary. Elijah first sings a short, accompanied recitative, not unlike what we heard in the music of Handel’s Messiah. The first chorus is highly polyphonic in announcing the flames from heaven before shifting to a more homophonic and deliberate style that uses longer note values to proclaim the central tenet of Western religion: “The Lord is God; the Lord is God! O Israel hear! Our God is one Lord, and we will have no other gods before the Lord.” After another recitative and another chorus, Elijah sings a very melismatic and virtuoso aria.

Elijah was very popular in its day, in both its English and German versions, both for music makers and musical audiences, and continues to be performed by choral societies today.

Video 10.2: Elijah

Performed by the Texas A&M Century Singers with orchestra and baritone soloist Weston Hurt

Listening Guide

- Composer: Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

- Composition: Excerpts from Elijah

- Date: 1846

- Genre: Recitative, choruses, and aria from an oratorio

- Form: Through-composed

- Nature of text:

- Elijah (recitative): O Thou, who makest Thine angels spirits; Thou, whose ministers are flaming fires: let them now descend!

- The People (chorus): The fire descends from heaven! The flames consume his offering! Before Him upon your faces fall! The Lord is God, the Lord is God! O Israel hear! Our God is one Lord, and we will have no other gods before the Lord.

- Elijah (recitative): Take all the prophets of Baal, and let not one of them escape you. Bring them down to Kishon’s brook, and there let them be slain.

- The People (chorus): Take all the prophets of Baal and let not one of them escape us: bring all and slay them!

- Elijah (aria): Is not His word like a fire, and like a hammer that breaketh the rock into pieces! For God is angry with the wicked every day. And if the wicked turn not, the Lord will whet His sword; and He hath bent His bow, and made it ready.

- Performing forces: Baritone soloist (Elijah), four-part chorus, orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It’s an oratorio composed for amateurs and professionals to perform at a choral festival.

- It uses traditional forms of accompanied recitative, chorus, and aria to tell a dramatic story.

- Other things to listen for:

- A much larger orchestra than heard in the oratorios of Handel

- A very melismatic and virtuoso aria in the style of Handel’s arias

- More flexible use of recitatives, arias, and choruses than in earlier oratorios

- More dissonance and chromaticism than in earlier oratorios

Felix was not the only musically precocious Mendelssohn in his household. In fact, the talent of his older sister Fanny (1805-1847) initially exceeded that of her younger brother. Born into a household of intelligent, educated, and socially sophisticated women, Fanny was given the same education as her younger brother. However, for her, as for most nineteenth-century married women from middle-class families, a career as a professional musician was frowned upon. Her husband, Wilhelm Hensel, supported her composing and presenting her music at private house concerts held at the Mendelssohn’s family residence. Felix also supported Fanny’s private activities, although he discouraged her from publishing her works under her own name. In 1846, Fanny went ahead and published six songs without seeking her husband’s or brother’s permission.

Musicians today perform many of the more than 450 compositions that Fanny wrote for piano, voice, and chamber ensemble. Among some of her best works are the four-movement Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 11, and several volumes of songs and piano compositions. This piano trio holds its own with the piano trios, piano quartets, piano quintets, and string quartets composed by other nineteenth-century composers, from Beethoven and Schubert to the Schumanns, Johannes Brahms, and Antonín Dvořák.

Video 10.3: Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Piano trio in D Minor, Op. 11, Movement 1

Music of the Schumanns

The couple became acquainted after Robert (1810-1856) moved to Leipzig and started studying piano with Friedrich Wieck, the father of the young piano prodigy Clara (1819-1896). The nine-year-old Clara was just starting to embark on her musical career. Throughout her teens, she would travel giving concerts, dazzling aristocratic and public audiences with her virtuosity. She also started publishing her compositions, which she often incorporated into her concerts. Her father, perhaps realizing what marriage would mean for the career of his daughter, refused to consent to her marriage with Robert Schumann, a marriage she desired, as she and Robert had fallen in love. They subsequently married in 1840, shortly before Clara’s twenty-first birthday, after a protracted court battle with her father.

Once the two were married, Robert’s musical activities became the couple’s priority. Robert began his musical career with aims of becoming a professional pianist. When he suffered weakness of the fingers and hands, he shifted his focus to music journalism and music composition. He founded a music magazine dedicated to showcasing the newer and more experimental music then being composed. In addition, he started writing piano compositions, songs, chamber music, and eventually orchestral music, the most important of which include four symphonies and a piano concerto, premiered by Clara in 1846. While Robert was gaining recognition as a composer and conductor, Clara’s composition and performance activities were restricted by her giving birth to eight children. Then in early 1854, Robert started showing signs of psychosis and, after a suicide attempt, was taken to an asylum. Although one of the more progressive hospitals of its day, this asylum did not allow visits from close relatives, so Clara would not see her husband for over two years, and then only in the two days before his death. After his death, Clara returned to a more active career as a performer; indeed, she spent the rest of her life supporting her children and grandchildren through her public appearances and teaching. Her busy calendar may have been one of the reasons why she did not compose after Robert’s death.

The compositional careers of Robert and Clara followed a similar trajectory. Both started their compositional work with short piano pieces that were either virtuoso showpieces or reflective character pieces that explored extra musical ideas in musical form. Theirs were just a portion of the many character pieces, especially those at a level of difficulty appropriate for the enthusiastic amateur pianist, published throughout Europe. After their marriage, they both merged poetic and musical concerns in Lieder (art songs); Robert published many song cycles, and he and Clara joined forces on a song cycle published in 1841. They also both turned to traditional genres, such as the sonata and larger four-movement chamber music compositions.

Focus Composition: Character Pieces by Robert and Clara Schumann

We’ll listen to two character pieces from the 1830s. Robert Schumann’s “Chiarina” was written between 1834 and 1835 and published in 1837 in a cycle of piano character pieces that he called Carnaval, after the festive celebrations that occurred each year before the beginning of the Christian season of Lent. Each short piece in the collection has a title, some of which refer to imaginary characters that Robert employed to give musical opinions in his music journalism. Others, such as “Chopin” and “Chiarina,” refer to real people, the former referring to the popular French-Polish pianist Fryderyk Chopin, and the later referring to the young Clara. At the beginning of the “Chiarina,” Robert inscribed the performance instruction “passionata,” meaning that the pianist should play the piece with passion. “Chiarina” is a little over a minute long and consists of two slightly contrasting musical phrases.

Video 10.4: “Chiarina” from Carnaval

Performed by Daniel Barenboim, 1979

Listening Guide

- Composer: Robert Schumann

- Composition: “Chiarina” from Carnaval

- Date: 1837

- Genre: Piano character piece

- Form: aaba’ba’

- Nature of text: The title refers to Clara

- Performing forces: Piano solo

- What we want you to remember about this piece:

- This is a character piece for solo piano.

- A dance-like mood is conveyed by its triple meter and moderately fast tempo.

- Other things to listen for:

- It has a leaping melody in the right hand and is accompanied by chords in the left hand.

- It uses two slightly different melodies.

The second character piece is one written by Clara Schumann between 1834 and 1836 and published as one piece in the collection Soirées Musicales in 1836 (a soirée was an event generally held in the home of a well-to-do lover of the arts where musicians, and other artists were invited for entertainment and conversation). Clara called this composition Ballade in D minor. The meaning of the title seems to have been vague almost by design, but most broadly considered, a ballade referred to a composition thought of as a narrative. As a character piece, it tells its narrative completely through music. Several contemporary composers wrote ballades of different moods and styles; Clara’s “Ballade” shows some influence of Chopin.

Clara’s Ballade, like Robert’s “Chiarina,” has a homophonic texture and starts in a minor key. A longer piece than “Chiarina,” the Ballade in D minor modulates to D major before returning to D minor for a reprise of the A section. Its themes are not nearly as clearly delineated as the themes in “Chiarina.” Instead, phrases start multiple times, each time slightly varied. You may hear what we call musical embellishments. These are notes the composer adds to a melody to provide variations. You might think of them like jewelry on a dress or ornaments on a Christmas tree. One of the most famous sorts of ornaments is the trill, in which the performer rapidly and repeatedly alternates between two pitches. We also talk of turns, in which the performer traces a rapid stepwise ascent and descent (or descent and ascent) for effect. You should also note that as the pianist in this recording plays, he seems to hold back notes at some moments and rush ahead at others: this is called rubato—that is, the robbing of time from one note to give it to another. We will see the use of rubato even more prominently in the music of Chopin.

Video 10.5: Soirées Musicales, Op. 6: No. 4, Ballade in D Minor

Performed by Jozef de Beenhouwer

Listening Guide

- Composer: Clara Wieck Schumann

- Composition: Ballade in D minor, Op. 6, No. 4

- Date: 1836

- Genre: Piano character piece

- Form: ABA

- Nature of text: This is a ballade—that is, a composition with narrative premises

- Performing forces: Piano

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- A lyrical melody over chordal accompaniment making this homophonic texture

- A moderate to slow tempo

- In duple time (in this case, four beats per measure)

- Other things to listen for:

- Musical themes that develop and repeat

- Musical embellishments in the form of trills and turns

Music of Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Fryderyk Chopin grew up in and around Warsaw, Poland, the son of a French father and Polish mother. His family was a member of the educated middle class; consequently, Chopin had contact with academics and wealthier members of the gentry and middle class. He learned as much as he could from the composition instructors in Warsaw—including the keyboard music of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven—before deciding to head off on a European tour in 1830. The first leg of the tour was Vienna, where Chopin expected to give concerts and then head farther west. About a week after his arrival, however, Poland saw political turmoil in the Warsaw uprising, which eventually led to Russian occupation of his home country. After great efforts, Chopin secured a passport and, in the summer of 1831, traveled to Paris, which would become his adopted home. Paris was full of Polish émigrés, who were well received within musical circles. After giving a few public concerts, Chopin was able to focus his attention on the salons, salons being smaller, semi-private events, similar to soirées, generally hosted by aristocratic women for artistic edification. There and as a teacher, he was in great demand and could charge heavy fees.

Much like Robert and Clara Schumann, Chopin’s first compositions were designed to impress his audiences with his virtuoso playing. As he grew older and more established, his music became more subtle. In addition, like the Schumanns, he composed pieces appropriate in difficulty for the musical amateur as well as work for virtuosos such as himself. Unlike many of the other composers we have discussed, Chopin wrote piano music almost exclusively. He was best known for character pieces, such as mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes, etudes, ballades, polonaises, and preludes.

Focus Composition: Chopin Mazurka in F Minor, Op. 7, No. 1 (1832)

The composition on which we will focus is the Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, No. 1, which was published in Leipzig in 1832 and then in Paris and London in 1833. The mazurka is a Polish dance, and mazurkas were rather popular in Western Europe as exotic stylized dances. Mazurkas are marked by their triple meter in which beat two rather than beat one gets the stress. They are typically composed in strains and are homophonic in texture. Chopin sometimes incorporated folk-like sounds in his mazurkas, sounds such as drones and augmented seconds. A drone is a sustained pitch or pitches. The augmented second is an interval that was commonly used in Eastern European folk music but very rarely in the tonal music of Western European composers.

These characteristics can be heard in the Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, No. 1, together with the employment of rubato. Chopin was the first composer to widely request that pianists use rubato when playing his music.

Video 10.6: Chopin Mazurka Op. 7 No. 1 performed by Arthur Rubinstein (24/154)

Listening Guide

- Composer: Fryderyk Chopin

- Composition: Mazurka in F Minor, Op. 7, No. 1

- Date: 1836

- Genre: Piano character piece

- Form: aaba’ba’ca’ca

- Nature of text: The title indicates a stylized dance based on the Polish mazurka

- Performing forces: Solo piano

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- This mazurka is in triple time with an emphasis on beat two.

- The texture is homophonic.

- Chopin asks the performer to use rubato.

- Other things to listen for:

- Its “c” strain uses a drone and augmented seconds.

Music of Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was born in Doborján, Hungary (now Raiding, Austria). His father, employed as a steward for a wealthy family, was an amateur musician who recognized his son’s talent. A group of Hungarian noblemen sponsored him with a stipend that enabled Franz to pursue his musical interest in Paris. There, he became the friend of Mendelssohn, Hugo, Chopin, Delacroix, George Sand, and Berlioz; these friends influenced him to become part of the French Romanticism movement.

Also, in Paris in 1831, Liszt attended a performance of virtuoso violinist Paganini, who was touring. Paganini’s style and success helped make Liszt aware of the demand for a solo artist who performed with showmanship. The ever-growing public audiences desired gifted virtuoso soloist performers at the time. Liszt, one of the best pianists of his time, became a great showman who knew how to energize an audience. Up until Liszt, the standard practice of performing piano solos was with the solo artist’s back to the audience. This limited—and blocked—the audience from viewing the artist’s hands, facial expression, and musical nuance. Liszt changed the entire presentation by turning the piano sideways so the audience could view his facial expressions and the way his fingers interacted with the keys, from playing loud and thunderously to gracefully light and legato. Liszt possessed great charisma and performance appeal; indeed, he had a following of young ladies that idolized his performances. During his career of music stardom, Liszt never married and was considered one of the most eligible bachelors of the time. However, he did have several “relationships” with different women, one of whom was the novelist Countess Marie d’Agoult, who wrote under the pen name of Daniel Stern. She and Liszt traveled to Switzerland for a few years, and they had three children, including Cosima, who ultimately married Wagner.

While at the height of his performance career, Liszt retreated from his piano soloist career to devote all his energy to composition. He moved to Weimar in 1948 and assumed the post of court musician for the Grand Duke, remaining in Weimar until 1861. There, he produced his greatest orchestral works. His position in Weimar included the responsibility as director to the Grand Duke’s opera house. In this position, Liszt could influence the public’s taste in music and construct musical expectations for future compositions. And he used his influential position to program what Wagner called “Music of the Future.” Liszt and Wagner both advocated and promoted highly dramatic music in Weimar, with Liszt conducting the first performances of Wagner’s Lohengrin and Belioz’s Benevenuto Cellini, as well as many other contemporary compositions.

While in Weimar, Liszt began a relationship with a woman who had a tremendous influence on his life and music. A wife of a nobleman in the court of the Tsar, Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittenstein met and fell in love with Liszt on his final performance tour of Russia. Later she left her husband and moved to Weimar to be with Liszt. She assisted Liszt in writing literary works, among which included a fabricated biography by Liszt on the Life of Chopin and a book on “Gypsy,” a book considered eccentric and inaccurate.

While Liszt had an eventful romantic life, he remained a Roman Catholic, and he eventually sought solitude in the Catholic Church. His association with the church led to the writing of his major religious works. He also joined the Oratory of the Madonna del Rosario and studied the preliminary stage for priesthood, taking his minor orders and becoming known as the Abbé Liszt. He dressed as a priest and composed Masses, oratorios, and religious music for the church.

Still active at the age of seventy-five, he earned respect from England as a composer and was awarded an honor in person by Queen Victoria. Returning from this celebration, he met Claude Debussy in Paris, then journeyed to visit his widowed daughter Cosima in Bayreuth and attended a Wagnerian Festival. He died during that festival, and even on his deathbed dying of pneumonia, Liszt named Wagner’s Tristan as one of the “Music of the Future” masterpieces.

Liszt’s primary goal in music composition was pure expression through the idiom of tone. His freedom of expression necessitated his creation of the symphonic poem, sometimes called a tone poem—a one-movement program piece written for orchestra that portrays images of a place, story, novel, landscape, or non-musical source or image. This form utilizes transformations of a few themes through the entire work for continuity. The themes are varied by adjusting the rhythm, harmony, dynamics, tempos, instrumental registers, instrumentation in the orchestra, timbre, and melodic outline or shape. By making these slight-to-major adjustments, Liszt found it possible to convey the extremes of emotion—from love to hate, war to peace, triumph to defeat—within a thematic piece. His thirteen symphonic poems greatly influenced the nineteenth century, an influence that continues through today. Liszt’s most famous piece for orchestra is the three-portrait work Symphony after Goethe’s Faust (the portraits include Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles). A similar work, his Symphony of Dante’s Divine Comedy, has three movements: Inferno, Purgatory, and Vision of Paradise. His most famous of the symphonic poems is Les Preludes (The Preludes), written in 1854.

His best-known works include nineteen Hungarian Rhapsodies, Piano concertos, Mephisto Waltzes, Faust Symphony, and Liebesträume.

Focus Composition: Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

Video 10.7: Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 performed by Jeneba Kanneh-Mason

Listening Guide

- Composer: Franz Liszt

- Composition: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

- Date: 1847

- Genre: The second of a set of 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies

- Performing forces: Piano solo

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- Widely popular, this piece offers the pianist the opportunity to reveal exceptional skill as a virtuoso while providing the listener with an immediate and irresistible musical appeal.

- Interest in this piece is rooted in the period’s interests in “Exoticism” (music from other cultures).

- This piece was used in many animated classic cartoons in contemporary culture, including “Tom and Jerry,” “Bugs Bunny,” “Woody Woodpecker,” and others.

- Other things to listen for:

- Listen to the dance rhythms and strong pulse even at the slower tempos.

- The piece begins with the “lasson,” a dramatic introduction that is followed by the “friska,” an energy-building section that builds to a tempest of sound and momentum.

Music of Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was born in France in La Côte-Saint-André, Isère, near Grenoble. His father was a wealthy doctor and planned on Hector’s pursuing the profession of a physician. At the age of eighteen, Hector was sent to study medicine in Paris. Music at the Conservatory and at the Opera, however, became the focus of his attention. A year later, his family grew alarmed when they realized that the young student had decided to study music instead of medicine.

At this time, Paris was in a Romantic revolution. Berlioz found himself in the company of novelist Victor Hugo and painter Delacroix. No longer receiving financial support from his parents, the young Berlioz sang in the theater choruses, performed musical chores, and gave music lessons. As a young student, Berlioz was amazed and intrigued by the works of Beethoven. Berlioz also developed interest in Shakespeare, whose popularity in Paris had recently increased with the performance of his plays by a visiting British troupe. Hector became impassioned with the Shakespearean characters of Ophelia and Juliet as they were portrayed by the alluring actress Harriet Smithson. Berlioz became obsessed with the young actress and overwhelmed by sadness due to her lack of interest in him as a suitor. Berlioz became known for his violent mood swings, a condition known today as manic depression.

In 1830, Berlioz earned his first recognition for his musical gift when he won the much sought-after Prix de Rome. This highly esteemed award provided him a stipend and the opportunity to work and live in Paris, thus providing Berlioz with the chance to complete his most famous work, the Symphonie Fantastique, that year.

Upon his return to Rome, he began his intense courtship of Harriet Smithson. Both her family and his vehemently opposed their relationship. Several violent and arduous situations occurred, one of which involved Berlioz’s unsuccessfully attempting suicide. After recovering from this attempt, Hector married Harriet. Once the previously unattainable matrimonial goal had been attained, Berlioz’s passion somewhat cooled, and he discovered that it was Harriet’s Shakespearean roles that she performed, rather than Harriet herself, that really intrigued him. The first year of their marriage was the most fruitful for him musically. By the time he was forty, he had composed most of his famous works. Bitter from giving up her acting career for marriage, Harriet became an alcoholic. The two separated in 1841. Berlioz then married his long-time mistress Marie Recio, an attractive but average singer who demanded to perform in his concerts.

To supplement his income during his career, Berlioz turned to writing as a music critic, producing a steady stream of articles and reviews. He successfully utilized this vocation as a way to support his own works by persuading the audience to accept and appreciate them. His critical writing also helped to educate audiences so they could understand his complex and innovative pieces. As a prose writer, Berlioz wrote The Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. He also wrote Les Soirées de l’Orchestre’ (Evenings with the Orchestra), a compilation of his articles on musical life in nineteenth-century France, and an autobiography entitled Mémoires. Later in life, he conducted his music in all the capitals of Europe, except for Paris. It was one location where the public would not accept his work. The Parisian public would read his reviews and learn to welcome lesser composers, but they would not accept Berlioz’s music. As over the years, Berlioz saw his own works neglected by the public of Paris while they cheered and supported others, he became disgusted and bitter from the neglect. His final work composed to gain acceptance from Parisian audiences was the opera Béatrice et Bénédict with his own libretto based upon Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing. But the Parisian public did not appreciate it. After this final effort, the disillusioned and embittered Berlioz composed no more in his seven remaining years, dying rejected and tormented at the age of sixty-six. Only after his death would France appreciate his achievements.

His operas include Benvenuto Cellini, Le Troyens, Béatrice et Bénédict, Les Francs-Juges (never performed, score missing sections), Grande Messe des Morts (Requiem), La Damnation de Faust, Te Deum, and L’Enfance du Christ. His major orchestral compositions include Symphonie Fantastique, Harold en Italie, Romeo et Juliette, The Corsair, King Lear, and Grande Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale. Berlioz is credited for changing the modern sound of orchestras.

Focus Composition: Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14, 1st movement

Video 10.8: Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14, 1st movement (watch until 15:07)

Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique is important for several reasons: it is a program symphony, it incorporates an idée fixe (a recurring theme representing an ideology or person that provides continuity through a musical work), and it contains five movements rather than the four of most symphonies.

Listening Guide

- Composer: Hector Berlioz

- Composition: Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14: 1st movement Reveries—Passions

- Date: 1830

- Genre: Symphony, first movement

- Form: Sonata

- Performing forces: Full symphony orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The largo (slow) opening is pensive and expressive, depicting the depression, the joy, and the fruitless passion Berlioz felt. It is followed by a long and very fast section with a great amount of expression, with the idée fixe (a short recurring musical theme/motive associated with a person, place, or idea) indicating the appearance of his beloved.

- The title for the movement is “Dreams, Passions.” It represents his uneasy and uncertain state of mind. The mood quickly changes as his love appears to him. He reflects on the love inspired by her. He notes the power of his enraged jealousy for her and of his religious consolation at the end.

- Other things to listen for:

- Berlioz is known for being one of the greatest orchestrators of all time. He even wrote the first comprehensive book on orchestration. He always thought in terms of the exact sound (tone or timbre) of the orchestra and the mixture of individual sounds to blend through orchestration. He gave very detailed instructions to the conductor and individual performers regarding articulations and how he wanted them to play. Listen to the subtleties and nuance of the performance. Berlioz left little up to chance, since he was so thorough in his compositions.

Music of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Whereas Berlioz’s program symphony might be heard as a radical departure from earlier symphonies, the music of Johannes Brahms is often thought of as breathing new life into classical forms. For centuries, musical performances were of compositions by composers who were still alive and working. In the nineteenth century, that trend changed. By the time that Johannes Brahms was twenty, over half of all music performed in concerts was by composers who were no longer living; by the time that he was forty, that amount increased to over two-thirds. Brahms knew and loved the music of forebears such as Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. He wrote in the genres they had developed, including symphonies, concertos, string quartets, sonatas, and songs. To these traditional genres and forms, he brought sweeping nineteenth-century melodies, much more chromatic harmonies, and the forces of the modern symphony orchestra. He did not, however, compose symphonic poems or program music as did Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt.

Brahms himself was keenly aware of walking in Beethoven’s shadow. In the early 1870s, he wrote to conductor friend Hermann Levi, “I shall never compose a symphony.” Continuing, he reflected, “You have no idea how someone like me feels when he hears such a giant marching behind him all of the time.” Nevertheless, some six years later, after a twenty-year period of germination, he premiered his first symphony. Brahms’s music engages Romantic lyricism, rich chromaticism, thick orchestration, and rhythmic dislocation in a way that clearly goes beyond what Beethoven had done. Still, his intensely motivic and organic style and his use of a four-movement symphonic model that features sonata, variations, and ABA forms are indebted to Beethoven.

The third movement of Brahms’s First Symphony is a case in point. It follows the ABA form, as had most moderate-tempo, dance-like third movements since the minuets of the eighteenth-century symphonies and scherzos of the early nineteenth-century symphonies. This movement uses more instruments and grants more solos to the woodwind instruments than earlier symphonies did (listen especially for the clarinet solos). The musical texture is thicker as well, even though the melody always soars above the other instruments. Finally, this movement is more graceful and songlike than any minuet or scherzo that preceded it. In this regard, it is more like the lyrical character pieces of Chopin, Mendelssohn, and the Schumanns than like most movements of Beethoven’s symphonies. But it does not have an extra musical referent; in fact, Brahms’s music is often called “absolute” music—that is, music for the sake of music. The music might call to a listener’s mind any number of pictures or ideas, but they are of the listener’s imagination, from the listener’s interpretation of the melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and textures written by Brahms. In this way, such a movement is very different than a movement from a program symphony such as Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. Public opinion has often split over program music and absolute music. What do you think? Do you prefer a composition in which the musical and extra musical are explicitly linked, or would you rather make up your own interpretation of the music, without guidance from a title or story?

Focus Composition: Brahms Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68, III

Video 10.9: Brahms Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68, III

Listening Guide

- Composer: Johannes Brahms

- Composition: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, III; un poco allegretto e grazioso (a little allegretto and graceful)

- Date: 1876

- Genre: Symphony

- Form: ABA moderate-tempo, dancelike movement from a symphony

- Performing forces: Romantic symphony orchestra, including two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, one contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, violins (first and second), violas, cellos, and double basses.

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- Its lilting tuneful melodies transform the scherzo mood into something more romantic.

- It is in ABA form.

- It is in A-flat major (providing respite from the C minor pervading the rest of the symphony).

- Other things to listen for:

- The winds as well as the strings get the melodic themes from the beginning.

Music of Nationalism

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, political and cultural nationalism strongly influenced many creative works of the nineteenth century. We have already observed aspects of nationalism in the piano music of Chopin and Liszt. Later nineteenth-century composers invested even more heavily in nationalist themes.

Nationalism, found in many genres, is marked using folk songs or nationalist themes in operas or instrumental music. Nationalist composers of different countries include:

- Russian composers such as Modest Mussorgsky, Alexander Borodin, and Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (members of the “Kuchka”);

- Bohemian composers such as Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana;

- Hungarian composers such as Liszt;

- Scandinavian composers such as Edvard Grieg and Jean Sibelius;

- Spanish composers such as Enrique Granados, Joaquin Turina, and Manuel de Falla; and

- British composers such as Ralph Vaughn Williams.

Composers looked to their native as well as exotic (from other countries) music to add to their palette of ideas. Nationalism was expressed in several ways:

- Songs and dances of native people

- Mythology: dramatic works based on folklore of peasant life (Tchaikovsky’s Russian fairy-tale operas and ballets)

- Celebration of a national hero, historic event, or scenic beauty of a country

Music of Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884)

Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) was born in Litomysl, Bohemia, while under Austrian rule (now the Czech Republic). Smetana was the son of a brewer and violinist and his father’s third wife. Smetana was a talented pianist who gave public performances from the age of six. Bohemia under Austrian rule was politically very volatile. In 1848, Smetana aligned himself with those seeking independent statehood from Austria. After that revolution was crushed, Prague and the surrounding areas were brutally suppressed—especially those areas and people suspected of being sympathetic to Bohemian nationalism. In 1856, Smetana left for Sweden to accept a conductorship post. He hoped to follow in the footsteps of such music predecessors as Liszt. He thus expresses his admiration, “By the grace of God and with His help, I shall one day be a Liszt in technique and a Mozart in composition,” as he wrote in a diary entry according to this biography.

As a composer, Smetana began incorporating nationalist themes, plots, and dances in his operas and symphonic poems. He founded the Czech national school after he left Sweden and was a pioneer at incorporating Czech folk tunes, rhythms, and dances into his major works. Smetana returned to Bohemia in 1861 and assumed his role as national composer. He worked to open and establish a theater venue in Prague where performances would be performed in their native tongue. Of his eight original operas, seven are still performed in native tongue today. One of these operas, The Bartered Bride, was and is still acclaimed. He composed several folk dances, including polkas for orchestra. These polkas incorporated the style and levity of his Bohemian culture.

Selected Compositions

Video 10.10: Louisa’s Polka, performed by the Brno State Philharmonic Orchestra, 2015

Smetana also is known for composing the cycle of six symphonic poems entitled My Country. These poems are program music, representing the beautiful Bohemian countryside, Bohemian folk dance and song rhythms, and the pageantry of Bohemian legends. The first of these symphonic poems is called Má vlast (My Fatherland) and is symbolic program music representing his birthplace.

Video 10.11: Má vlast (My Fatherland) performed by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, 1984

The second of these, Vltava (The Moldau), is recognized as Smetana’s greatest orchestral work. Notes in the conductor’s score state:

The Moldau represents an exceptional expression of patriotic or nationalistic music. The musical poem reflects the pride, oppression, and hope of the Bohemian people. Two springs pour forth in the shade of the Bohemian Forest, one warm and gushing, the other cold and peaceful. Their waves, gaily flowing over rocky beds, join and glisten in the rays of the morning sun. The forest brook, hastening on, becomes the river Vltava (Moldau). Coursing through Bohemia’s valleys, it grows into a mighty stream. Through thick woods it flows, as the gay sounds of the hunt and the notes of the hunter’s horn are heard ever nearer. It flows through grass-grown pastures and lowlands where a wedding feast is being celebrated with song and dance. At night wood and water nymphs revel in its sparkling waves. Reflected on its surface are for- tresses and castles—witnesses of bygone days of knightly splendor and the vanished glory of fighting times. At the St. John Rapids the stream races ahead, winding through the cataracts, heaving on a path with its foaming waves through the rocky chasm into the broad river bed—finally. Flowing on in majestic peace toward Prague—finally. Flowing on in majestic peace toward Prague and welcomed by time-honored Vysehrad (castle.) Then it vanishes far beyond the poet’s gaze. —Preface to the original score, Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York, The Concert Companion, p. 672.

Focus Composition: Bedřich Smetana, The Moldau (Vlatava)

Video 10.12: Vltava (The Moldau) by Bedřich Smetana, BBC Symphony, Vilem Tausky: Conductor

Listening Guide

- Composer: Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884)

- Composition: The Moldau (Vlatava)

- Date: 1874

- Genre: Symphonic poem

- Form: Symphonic poem (tone poem)

- Performing forces: Piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four French horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, triangle, cymbals, harp, and strings

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The Moldau (Vlatava) is a programmatic symphonic poem portraying the story of the main river in Bohemia as it flows through Smetana’s homeland countryside. Each section portrays a different scene, often contrasting, that the river encounters.

- This piece is a good representation of Czech nationalism and also of a romantic setting of nature.

- The composer wrote the work following a trip he took down the river as part of a larger cycle of six symphonic poems written between 1874 and 1879 entitled Má Vlast (My Country).

- Note that each section of the work has its own descriptive title in bold print.

Music of Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Antonín Dvořák (pronounced Antoneen Duhvorszahk) was born in a Bohemian village of Nelahozeves near Prague. Following in Smetana’s footsteps, Dvořák became a leading composer in the Czech nationalism music campaign. Indeed, Dvořák and Smetana are considered the founders of the Czech national school. Dvořák, at the age of sixteen, moved to Prague. As a young aspiring violinist, Dvořák earned a seat in the Czech National Theater. Dvořák learned to play viola and became a professional violist; for a time in his career, he performed under Smetana. Dvořák became recognized by Brahms, who encouraged Dvořák to devote his energy to composing. Early in his career, he was musically under the German influence of Beethoven, Brahms, and Mendelssohn. Later, however, Dvořák explored his own culture, rooting his music in the dances and songs of Bohemia. Indeed, he never lost touch with his humble upbringing by his innkeeper and butcher father.

Dvořák’s compositions received favorable recognition abroad and reluctant recognition at home. From 1892 to 1895, Dvořák served as director of the National Conservatory in the United States. During this time, his compositions added American influences to the Bohemian. He fused “old world” harmonic theory with “new world” style. Very interested in American folk music, Dvořák took as one of his pupils an African-American baritone singer named Henry T. Burleigh, who was an arranger and singer of spirituals. You can hear Harry T. Burleigh sing the spiritual “Go Down Moses.” Dvořák’s admiration and enthusiasm for the African-American spiritual is conveyed as he stated,

I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. —Interviewed by James Creelman, New York Herald, May 21, 1893

The spirituals, along with Native American and cowboy songs, interested Dvořák and influenced his compositions for years to come. His love for this American folk music was contagious and soon spread to other American composers. Up until this point, American composers were under the heavy influence of their European counterparts. Dvořák’s influence and legacy as an educator and composer can be traced in the music of Aaron Copland and George Gershwin.

Something to Think About

Although he gained much from his time in America, Dvořák yearned for his homeland, to which he returned after three years away, resisting invitations from Brahms to relocate in Vienna. Dvořák desired the simpler life of his homeland, where he died in 1904, shortly after his last opera, Armida, was first performed.

Can you think of any other famous musicians or composers who were uprooted from their homeland and poured their yearning for their homeland into their music?

Music for Orchestra

In his lifetime, Dvořák wrote in various music forms, including the symphony. He composed nine symphonies in all, with his most famous being the ninth, From the New World (1893). This symphony was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, which premiered it in New York on December 16, 1893, the same year as its completion. The symphony was partially inspired by a Czech translation of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Hiawatha.

Dvořák also composed a cello concerto for solo instrument and orchestra, a violin concerto, and a lesser-known piano concerto. Dvořák received recognition for Romance for solo violin and orchestra and Silent Woods for cello and orchestra. These two pieces make significant contributions to the solo repertoire for both string instruments.

Dvořák composed several piano duets that he later orchestrated for symphony orchestra. They include his ten Legends, two sets of Slavonic Dances, and three Slavic Rhapsodies. His overtures include In Nature’s Realm, My Home, Carnival, Hussite, and Othello. He also composed a polonaise Scherzo Capriccioso and the much-admired Serenade for Strings. His symphonic poems include The World Dove, The Golden Spinning-Wheel, and The Noonday Witch.

Music for Chamber Ensembles

Dvořák also composed chamber music, including fourteen string quartets. No. 12, the “American” Quartet, was written in 1893, the same year as the New World Symphony. Also from the American period, Dvořák composed the G major Sonatinas for violin and piano, whose second movement is known as “Indian Lament.” Of the four remaining found Dvořák piano trios, the Dumky trio is famous for using the Bohemian national dance form. His quintets for piano and strings or strings alone for listening enjoyment are much appreciated, as are his string sextet and the trio of two violins and viola, Terzetto.

Humoresque in G-flat Major is the best known of the eight Dvořák piano pieces placed in a set. He also composed two sets of piano duets entitled Slavonic Dances.

Operas

From 1870 to 1903, Dvořák wrote ten operas. The famous aria "O Silver Moon" (1900) from Rusalka is one of his most famous pieces. Dvořák wrote many of his operas with village theaters and comic village plots in mind, much the same as Smetana’s The Bartered Bride.

Choral and Vocal Works

Several of Dvořák’s choral works were composed for many of the amateur choral societies, such as those found in Birmingham, Leeds, and London in England. The oratorio St. Ludmilla was composed for such societies, as were settings of the Mass, Requiem Mass, and the Te Deum, which was first performed in 1892 in New York. Earlier choral works and settings, such as Stabat Mater and Psalm CXLIX, were performed in Prague 1879-1880.

Dvořák composed several songs, including the appreciated set of Moravian Duets for soprano and contralto. The most famous of his vocal pieces is the “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” which is the fourth in the Seven Gypsy Songs, opus 55, set.

Focus Composition: Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 (From the New World) Movement 2

Video 10.13: Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 (From the New World) Movement 2

Listening Guide

- Composer: Antonín Dvořák

- Composition: Symphony No. 9 From the New World, movement 2 Largo

- Date: 1893

- Genre: Symphony

- Performing forces: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Sir George Solti, conductor

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The theme. The “coming home theme” is said to possibly be from a negro spiritual or Czech folk tune. It is introduced in what some call the most famous English horn solo.

- Other things to listen for:

- The weaving of these very beautiful but simple melodies. Listen to how “western American” the piece sounds at times. American music (western, spirituals, and folk) had a profound influence on Dvořák’s compositions.

You are encouraged to listen to the entire symphony. For more information, visit Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 9 “From the New World” analysis by Gerard Schwarz Part 1 from Khan Academy.

Music of Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Pyotr (Peter) Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, a small mining town in Russia. He was a son of a government official and started taking piano at the age of five, though his family intended him to have a career as a government official. His mother died of cholera when he was fourteen, a tragedy that had a profound and lasting effect on him. He attended the aristocratic school in St. Petersburg called the School of Jurisprudence and, upon completion, obtained a minor government post in the Ministry of Justice. Nevertheless, Pyotr always had a strong interest in music and yearned to study it.

At the age of twenty-three, he resigned his government post and entered the newly created Conservatory of St. Petersburg to study music. From the age of twenty-three to twenty-six, he studied intently and completed his study in three years. His primary teachers at the conservatory were Anton Rubinstein and Konstantin Zarembe, but he himself taught lessons while he studied. Upon completion, Tchaikovsky was recommended by Rubinstein, director of the school as well as teacher, to a teaching post at the new conservatory of Moscow. The young professor of harmony had full teaching responsibilities with long hours and a large class. Despite his heavy workload, his twelve years at the conservatory saw the composing of some of his most famous works, including his first symphony. At the age of twenty-nine, he completed his first opera, Voyevoda, and composed the Romeo and Juliet overture. At the age of thirty-three, he started supplementing his income by writing as a music critic and composed his second symphony, his first piano concerto, and his first ballet, Swan Lake.

The reception of his music sometimes included criticism, and Tchaikovsky took criticism very personally, being prone as he was to (attacks of) depression. These bouts with depression were exacerbated by an impaired personal social life. To calm and smooth that personal life, Tchaikovsky entered a relationship and marriage with a conservatory student named Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova in 1877. She was star-struck and had fallen immediately and rather despairingly in love with him. His pity for her soon turned into unmanageable dislike to the point that he avoided her at all costs. Once in a fit of depression and aversion, he even strolled into the icy waters of the Moscow River to avoid her. Many contemporaries believe the effort was a suicide attempt. A few days later, nearly approaching a complete mental breakdown, he sought refuge and solace, fleeing to his brothers in St. Petersburg. The marriage lasted less than a month.

At this darkest hour for Tchaikovsky, a kind, wealthy benefactress who admired his music became his sponsor. Her financial support helped restore Tchaikovsky to health, freed him from his burdensome teaching responsibilities, and permitted him to focus on his compositions. His benefactor was a widowed industrialist, Nadezhda von Meck, who was dominating and emotional and who loved his music. From her secluded estate, she raised her eleven children and managed her estate and railroads. Due to the social norms of the era, she had to be very careful to make sure that her intentions in supporting the composer went toward his music and not toward the composer as a man; consequently, they never met one another other than possibly through the undirected mutual glances at a crowded concert hall or theater. They communicated through a series of letters to one another, and this distance letter-friendship soon became one of fervent attachment.

In his letters to Meck, Tchaikovsky would explain how he envisioned and wrote his music, describing it as a holistic compositional process, with his envisioning the thematic development to the instrumentation being all one thought. The secured environment she afforded Tchaikovsky enabled him to compose unrestrainedly and very creatively. In appreciation and respect for his patron, Tchaikovsky dedicated his fourth symphony to Meck. He composed that work in his mid-thirties, a decade when he premiered his opera Eugene Onegin and composed the 1812 Overture and Serenade for Strings.

Tchaikovsky’s music ultimately earned him international acclaim, leading to his receiving a lifelong subsidy from the tsar in 1885. He overcame his shyness and started conducting appearances in concert halls throughout Europe, making his music the first of any Russian composer to be accepted and appreciated by Western music consumers. At the age of fifty, he premiered Sleeping Beauty and The Queen of Spades in St. Petersburg. A year later, in 1891, he was invited to the United States to participate in the opening ceremonies for Carnegie Hall. He also toured the United States, where he was afforded impressive hospitality. He grew to admire the American spirit, feeling awed by New York’s skyline and Broadway. He wrote that he felt he was more appreciated in America than in Europe.

While his composition career sometimes left him feeling dry of musical ideas, Tchaikovsky’s musical output was astonishing and included at this later stage of his life two of his greatest compositions: The Nutcracker, a ballet, and Iolanta, an opera. Both premiered in St. Petersburg. He conducted the premier of his sixth symphony, Pathétique, in St. Petersburg as well but received only a lukewarm reception, partially due to his shy, lack-luster personality. The persona carried over into his conducting technique that was rather reserved and subdued, leading to a less than emotion-packed performance by his orchestra.

A few days after the premier, while he was still in St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky ignored warnings against drinking unboiled water, warnings due to the current prevalence of cholera there. He contracted the disease and died within a week at the age of fifty-three years old. Immediately upon his tragic death, the Symphonie Pathétique earned great acclaim that it has held ever since.