13 Romantic Period: Opera

Learning Objectives

- Explain how Giuseppe Verdi’s Romantic Period operatic style reflects the Italian bel canto tradition.

- Explain how Romantic Period opera differs from Classical Period opera in the distinctions between recitative and aria and the use of the orchestra.

- Analyze Verdi’s melodic gift and his combination of comedy and tragedy in scenes from Act III of Rigoletto.

- Compare and contrast the operatic styles of Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner.

- Explain how Richard Wagner’s music dramas reflect Wagner’s background in symphonic music, particularly the symphonies of Beethoven.

- Explain the concept of a Leitmotiv and identify their use in the final scene from The Valkyrie.

- Explain how Leitmotivs influenced the development of film music.

Francis Scully

Romantic Opera

Given Romantic composers’ interest in connecting to other arts (literature, visual art), opera is obviously going to be a big deal in the nineteenth century. Like all art and music in the Romantic era, opera is going to get more “serious.” It’s no longer simply a vehicle for spectacle and entertainment.

There are many great opera composers and operas in the Romantic Period, but two names tower above them all: the Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi and the German opera composer Richard Wagner.

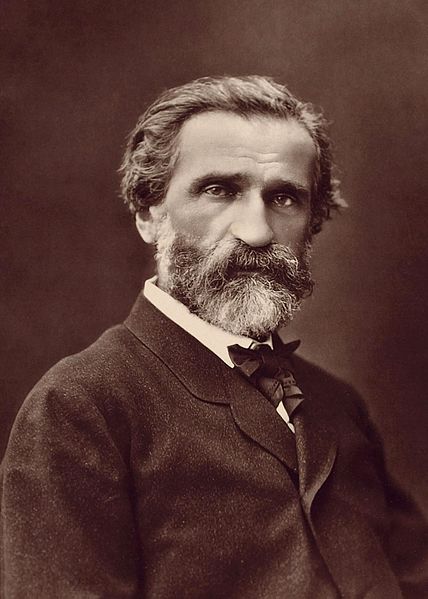

Verdi, Giuseppe (1813-1901)

Verdi is considered the greatest of Italian opera composers. He studied music in Milan, home of the famous La Scala Opera House (still one of the major opera houses of the world), and he composed opera almost exclusively in his career. He had his first big success with Nabucco (1842), and in the 1850s, he brought out his trio of “smash hits” Rigoletto (1851), Il Trovatore (1853), and La Traviata (1853). Verdi was politically involved as a supporter of the Italian liberation movement. In his seventies, he wrote two of his greatest works, both based on Shakespeare: Falstaff and Otello. Other important works include Aida (1871) and a brilliant and dramatic Requiem Mass.

Verdi inherits a style of early nineteenth-century Italian opera known as “bel canto,” which literally means “beautiful singing.” For the bel canto composers like Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti, music was intended to showcase the beauty of the human voice. Verdi is similarly praised for his ability to foreground spectacular feats of virtuoso singing, and he is celebrated for his astonishing gift for writing memorable melodies. Verdi wrote some of the most beloved arias in the operatic repertoire, and they are often extracted for concert performances. Watch this aria (“La donna è mobile”) from Verdi’s opera Rigoletto and you’ll instantly recognize Verdi’s melodic gift:

Video 13.1: Rigoletto La Dona e mobile, performed by Luciano Pavarotti

Like his bel canto compatriots, Verdi values the beauty of the human voice as the basis of opera, and he writes a lot of gorgeous melodies that highlight this, but Verdi does not allow this emphasis on singers to overshadow his real interest, which is drama, placing vivid characters in extreme situations and ratcheting up the tension.

Dramatic Fluidity

If you recall from previous discussion of opera and the scenes in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, there was a clear distinction between the recitative and the aria (or ensemble). The recitative almost always had a simple harpsichord accompaniment and was musically less interesting. The arias and ensembles provided the musical interest. In a certain sense, the piece essentially switched back and forth between drama (recitative) and music (aria/ensemble). In the Romantic Period, however, composers were interested in creating a more fluid and unified opera, one in which the music works hand-in-hand with the drama continuously.

To do this, Romantic Period composers get rid of the harpsichord (the simple keyboard accompaniment, playing rolled chords underneath recitative) altogether. Instead, they use the orchestra throughout the whole opera. Of course, they still need some kind of recitative-like sections in order to clearly present plot action and dialogue, but now the orchestra plays more active, motivic, and dramatic music as opposed to the simple chords of 18th-century recitative. Notice in the two Romantic Period operas that we will watch that the distinction between aria and recitative is increasingly blurred.

Rigoletto (1851)

To get a sense of how Verdi unifies spectacular singing, memorable melodies, and intense drama, we will watch two scenes from Verdi’s 1851 opera Rigoletto.

Rigoletto was based on a play called “Le Roi s’amuse” (The King Amuses Himself) by the French Romantic writer Victor Hugo, who is best known for his novels The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1833) and Les Miserables (1862). The opera is set in the Italian city of Mantua during the 1500s, where the title character, Rigoletto, serves as the hunchbacked court jester to womanizing lothario, Duke of Mantua. In the aria that we heard above (“La donna è mobile”), the Duke of Mantua presents his womanizing philosophy of life (to paraphrase, something like “women…you can’t live with them, you can’t live without them, might as well have some fun with them”). Rigoletto typically mocks the various men whose wives and girlfriends fall for the Duke, and in the opera’s first scene, Count Monterone, one of the Duke’s victims who has been mercilessly taunted by Rigoletto, pronounces a curse on Rigoletto. Later in the opera, Rigoletto learns, much to his horror, that his precious young daughter Gilda has also been seduced by the Duke.

In the opera’s final act (Act III), Rigoletto plots his revenge against his employer by hiring the assassin Sparafucile to kill the Duke. But first, Rigoletto wants his daughter to see the Duke in the act of cheating on her. Rigoletto and Gilda perch outside of an inn where Sparafucile’s sister Maddalena has lured the Duke to set up the assassination. The Duke and Maddalena flirt with each other while Rigoletto and Gilda watch in horror. In this masterful ensemble, we hear the emotions of the four different characters at the same time. Verdi accomplishes this by using different rhythms, different melodic shapes, and different pitch ranges for each of the voices (Gilda = soprano, Maddalena = alto, Duke = tenor, Rigoletto = bass). What’s more, in this incisive scene, Verdi deftly combines tragedy (the anger and despair experienced by Rigoletto and Gilda) with comedy (the flirting and playfulness of Maddalena and the Duke’s exchange). We will start the scene with the Duke’s aria and observe again how the different sections of Romantic opera unfold more seamlessly than in Classical Period opera.

Video 13.2: Rigoletto, Verdi, Watch from 1:28:51 to 1:37:05

Listening Guide: Rigoletto from 1:28:51 to 1:37:05

| Time | Description |

|---|---|

| 1:28:51–1:31:15 | The Duke sings his trademark aria “La donna è mobile.” |

| 1:31:16–1:33:11 | Transitional section where the Duke woos Maddalena while Rigoletto and Gilda look on. |

| 1:33:12–1:37:05 | “Bella figlia dell’amore”: The quartet in which each character presents conflicting emotions. |

Following this scene, the Duke goes to sleep in the inn, where he sings another verse of “La donna è mobile” as he dozes off (Verdi is also cleverly reminding the audience of his “hit tune”). Maddalena, who has now fallen under the Duke’s spell, feels sympathy for him and pleads with her brother to spare his life. But Sparafucile is an honorable businessman and only agrees to spare the Duke if someone arrives at the inn before dawn, when Rigoletto agrees to return for the body. Gilda, who has snuck away from her father, overhears the exchange, and in the middle of a raging storm, knocks on the door, willing to sacrifice her life to save the Duke. In the morning, Rigoletto returns to the inn to pay Sparafucile the rest of his fee and gloat over the dead body of the Duke. Little does he know, the body that he’s collecting from Sparafucile is that of his own daughter! Rigoletto plans to take the body to dump in the river when he overhears the Duke waking up and singing (yet again) his signature tune. The playful melody delivers the shock to Rigoletto that the body in the body bag is not that of his nemesis. He opens it up to discover his daughter. This being opera, Gilda is just conscious enough to sing an impassioned duet as father and daughter say goodbye to each other and Gilda expires.

Video 13.3: Now watch from 1:46:55 to 1:58:10

Listening Guide: Rigoletto from 1:46:55 to 1:58:10

| Time | Description |

|---|---|

| 1:46:55–1:48:35 | Rigoletto prepares to meet Sparafucile. |

| 1:48:36–1:50:31 | Rigoletto receives the body from Sparafucile and he begins to celebrate. |

| 1:50:32–1:54:39 | The Duke sings “La donna è mobile” and Rigoletto realizes that his daughter is in the body bag. Gilda explains how she came to be Sparafucile’s victim. |

| 1:54:40–1:58:10 | Rigoletto and Gilda sing a tender duet as Gilda dies. Rigoletto realizes that Count Monterone’s curse has been fulfilled. |

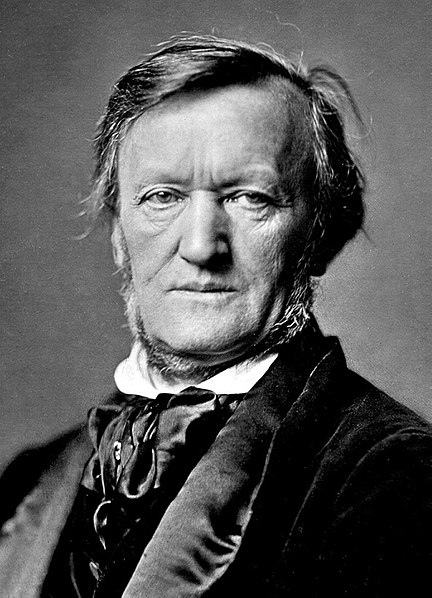

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Adapted from “Music of Richard Wagner,” Understanding Music

By Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, Jeffrey Kluball, & Elizabeth Kramer

Revised by Jonathan Kulp

Adapted by Francis Scully

If Verdi continued the long tradition of Italian opera, Richard Wagner provided a new path for German opera. Wagner (1813-1883) may well have been the most influential European composer of the second half of the nineteenth century. Never shy about self-promotion, Wagner himself clearly thought so. Wagner’s influence was both musical and literary. His dissonant and chromatic harmonic experiments even influenced the French, whose music belies their many verbal denouncements of Wagner and his music. His essays about music and autobiographical accounts of his musical experiences were widely followed by nineteenth-century individuals, from the average bourgeois music enthusiast to philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche. Most disturbingly, Wagner was rabidly anti-Semitic, and generations later, his writing and music provided propaganda for the Nazi Third Reich.

Born in Leipzig, Germany, Wagner initially wanted to be a playwright like Goethe, until as a teenager he heard the music of Beethoven and decided to become a composer instead. He was particularly taken by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the addition of voices as performing forces into the symphony, a type of composition traditionally written for orchestra. Seeing in this work an acknowledgment of the powers of vocal music, Wagner set about becoming an opera composer. Coming of age during a time of rising nationalism, Wagner criticized Italian opera as consisting of cheap melodies and insipid orchestration unconnected to its dramatic purposes, and he set about providing a German alternative. He called his operas “music dramas” in order to emphasize a unity of text, music, and action and declared that they would be Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total works of art.” As part of his program, he wrote his own librettos and aimed for what he called unending melody: the idea was for a constant lyricism, carried as much by the orchestra as by the singers.

Perhaps most importantly, Wagner developed a system of what scholars have come to call Leitmotivs. Leitmotivs, or “guiding motives,” are musical motives that are associated with a specific character, theme, or locale in a drama. Wagner integrated these musical motives in the vocal lines and orchestration of his music dramas at many points. Wagner believed in the flexibility of such motives to reinforce an overall sense of unity within his compositions, even if primarily at a subconscious level. Thus, while a character might be singing a melody line using one leitmotiv, the orchestration might incorporate a different leitmotiv, suggesting a connection between the referenced entities. The use of leitmotivs also reflects Wagner’s understanding of opera as a symbolic artform rather than a “realistic” form of drama. To that end, his mature operas are all based on either medieval legends (Tannhäuser [1845], Tristan und Isolde [1859], Parsifal [1882]) or Germanic mythology (The Ring of the Nibelungs [1876]).

Wagner also designed and built a theater for the performance of his own music dramas. The Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, Germany, was the first to use a sunken orchestra pit, and its huge backstage area allowed for some of the most elaborate sets of Wagner’s day. It was here that his famous cycle of music dramas, The Ring of the Nibelungen, was performed, starting in 1876. The Ring of the Nibelungen consists of four music dramas with over fifteen hours of music. Wagner took the story from a Nordic mythological legend that stems back to the Middle Ages. In it, a piece of gold is stolen from the Rhine River and fashioned into a ring, which gives its bearer ultimate power. The cursed ring changes hands, causing destruction around whoever possesses it. Eventually the ring is returned to the Rhine River, thereby closing the cycle. Into that story, which some may recognize from the much later fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Wagner interwove stories of the Norse gods and men. Wagner’s four music dramas trace the saga of the king of the gods, Wotan, as he builds Valhalla, the home of the gods, and attempts to order the lives of his children, including that of his daughter, the Valkyrie warrior Brünnhilde.

Focus Composition: Conclusion to The Valkyrie (1876)

In the excerpt we’ll watch from the end of The Valkyrie, the second of the four music dramas, Brünnhilde has gone against her father, and because Wotan cannot bring himself to kill her, he puts her to sleep before encircling her with flames, a fiery ring that both imprisons and protects his daughter. This excerpt provides several examples of the Leitmotivs for which Wagner is so famous. Their presence, often subtle, is designed to guide the audience through the drama. They include melodies, harmonies, and textures that represent Wotan’s spear, the god Loge—a shape-shifting life force that here takes the form of fire—sleep, the magic sword, and fate. The sounds of these motives are discussed briefly below and accompanied by excerpts from the musical score for those of you who can read musical notation.

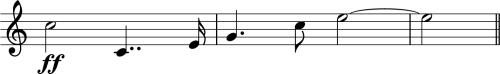

The first motive heard in the video you will watch is Wotan’s Spear. The spear represents Wotan’s power. In this scene, Wotan is pointing it toward his daughter Brünnhilde, ready to conjure the ring of fire that will both imprison and protect her. Representing a symbol of power, the spear motive is played here at a forte dynamic on piano. Here it descends in a minor scale that reinforces the seriousness of Wotan’s actions.

Audio ex. 13.1: Wotan’s Spear, from The Valkyries, Richard Wagner, composer

Wotan commands Loge to appear, and suddenly the music breaks out in a completely different style. Loge’s music—sometimes also referred to as the magic fire music—is in a major key and appears in upper woodwinds such as the flutes. Its notes move quickly with staccato articulations suggesting Loge’s free spirit and shifting shapes.

Depicting Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep, Wagner wrote a chromatic musical line that starts high and slowly moves downward. We call this phrase the Sleep motive:

Audio ex. 13.2: Brünnhilde’s sleep motive from The Valkyries, Richard Wagner, composer

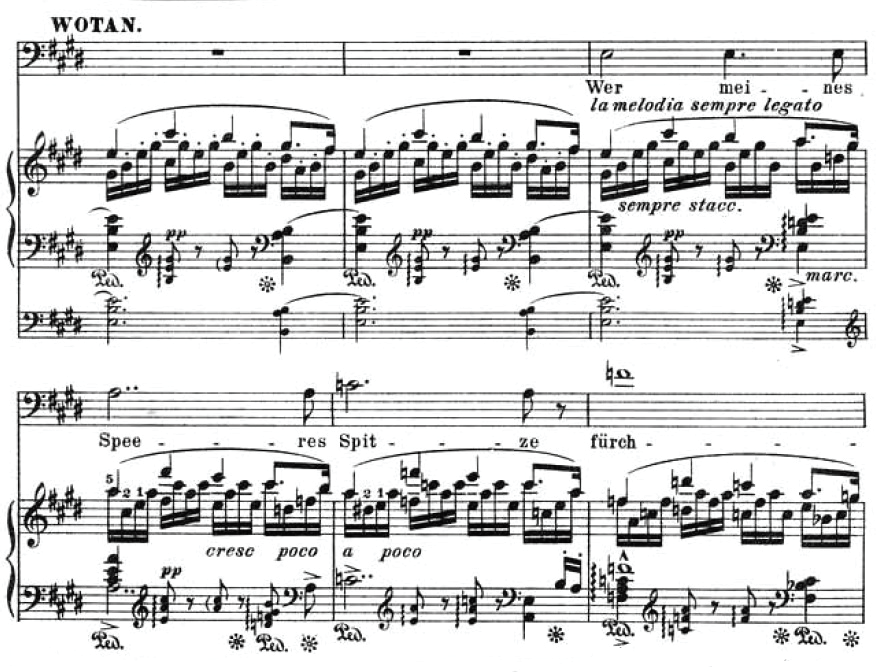

After casting his spell, Wotan warns anyone who is listening that whoever would dare to trespass the ring of fire will have to face his spear. As the drama unfolds in the next opera of the tetralogy, one character will do just that: Siegfried, Wotan’s own grandson. He will release Brünnhilde using a magic sword. The melody to which Wotan sings his warning with its wide leaps and overall disjunct motion sounds a little bit like the motive representing Siegfried’s sword.

Audio ex. 13.3: “Siegfried’s Sword” from The Valkyries, Richard Wagner, composer

One final motive is prominent at the end of The Valkyrie, a motive which is referred to as Fate. It appears in the horns and features three notes: a sustained pitch that slips down just one step and then rises the small interval of a minor third to another sustained pitch.

Now that you’ve been introduced to all of the leitmotivs in the excerpt, follow along with the listening guide. As you listen, notice how prominent the huge orchestra is throughout the scene, how it provides the melodies, and how the strong and large voice of the bass-baritone singing Wotan soars over the top of the orchestra (Wagner’s music required larger voices than earlier opera as well as new singing techniques). See if you can hear the Leitmotivs, there to absorb you in the drama. Remember that this is just one short scene from the midpoint of the approximately fifteen-hour-long tetralogy.

Video 13.4: Wotan’s Farewell, performed by Sir John Tomlinson

Listening Guide

- Composer: Richard Wagner

- Composition: The Valkyries, Final Scene: Wotan’s Farewell

- Date: 1870

- Genre: Music drama (or nineteenth-century German opera)

- Form: Through-composed, using Leitmotivs

- Nature of text:

Loge, hear! List to my word!

As I found thee of old, a glimmering flame,

as from me thou didst vanish,

in wandering fire;

as once I stayed thee, stir I thee now!

Appear! come, waving fire,

and wind thee in flames round the fell!

(During the following he strikes the rock thrice with his spear.)

Loge! Loge! appear!

He who my spearpoint’s sharpness feareth

shall cross not the flaming fire!

- Performing forces: Bass-baritone Wotan, large orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It uses Leitmotivs.

- The orchestra provides an “unending melody” over which the characters sing.

- Other things to listen for:

- Listen for the specific Leitmotivs.

Listening Guide: The Valkyries, Wotan’s Farewell

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Leitmotiv and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Descending melodic line played in octaves by the lower brass | Wotan’s spear: Just the orchestra |

| 0:08 | Wotan sings a motivic phrase that ascends; the orchestra ascends, too, supporting his melodic line | Löge, hör! Lausche hieher! Wie zuerst ich dich fand, als feurige Glut, wie dann einst du mir schwandest, als schweifende Lohe; wie ich dich band |

| 0:28 | Appears as Wotan transitions to new words still in the lower brass | Spear again: Bann ich dich heut’! |

| 0:29 | Trills in the strings and a rising chromatic scale introduce Wotan’s striking of his spear and producing fire introducing the . . . | Fire music: Herauf, wabernde Loge, umlodre mir feurig den Fels! Loge! Loge! Hieher! |

| 0:58 | fire music played by the upper woodwinds (flutes, oboes, and clarinets). | Fire music: Just the orchestra |

| 1:41 | Slower, descending chromatic scale in the winds represents Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep | Sleep: Just the orchestra |

| 2:06 | As Wotan sings again, his melodic line seems to allude to the sword motive, doubled by the horns and supported by a full orchestra. | Sword motive: Wer meines Speeres Spitze fürchtet, durchschreite das Feuer nie! |

| 2:40 | Lower brass prominently plays the sword motive while the strings and upper woodwinds play motives from the fire music; a gradual decrescendo | Sword motive; fire music continues: Just the orchestra |

| 4:05 | The horns and trombones play the narrow-raged fate melody as the curtain closes | Fate motive: Just the orchestra |

Something to Think About

Compare and contrast the operatic styles of Verdi (in Rigoletto) and Richard Wagner (in his opera The Valkyrie). Consider how the two composers use the voice, how they use the orchestra, and the subject matter. Which approach do you find more effective? Entertaining? Dramatically satisfying? Musically satisfying?

Leitmotifs in Lord of the Rings

Wagner’s Leitmotif technique was one of the most influential techniques to come out of the 19th century. Hollywood composers have been using it for many years to represent things like giant sharks in Jaws (John Williams, 1976), forces of evil in Star Wars, and many other ideas, characters, and objects in other films. You might find it interesting to watch this video about the Leitmotifs that are at work in the score for The Lord of the Rings.

Video 13.5

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we looked at the music of two of the giants of Romantic Period opera, the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi and the German composer Richard Wagner. Verdi hailed from the bel canto Italian tradition, which put the human voice at the center of the operatic spectacle. But Verdi never let his beautiful melodies hamper the passionate intensity of the drama. While Wagner’s operas are no less dependent on superhuman singing abilities, Wagner transformed the role of the orchestra in his works. Through the presentation and development of leitmotivs, the orchestra becomes an essential character in the drama, providing psychological commentary on the stage action, as well as propelling the action forward. Wagner returned to myths and legends for the literary material for his operas to create more of a symbolic artwork. While Wagner lived many years before the development of motion pictures, his Leitmotiv technique became an essential component of musical storytelling in film.