9.1 Introducing the Realm

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the realm’s physical geography. Identify each country’s main features and physical attributes and locate the realm’s main river systems.

- Understand the dynamics of the monsoon and how it affects human activities.

- Outline the early civilizations of South Asia and learn how they gave rise to the early human development patterns that have shaped the realm.

- Describe how European colonialism impacted the realm.

- Learn about the basic demographic trends the realm is experiencing. Understand how rapid population growth is a primary concern for the countries of South Asia.

The Physical Geography

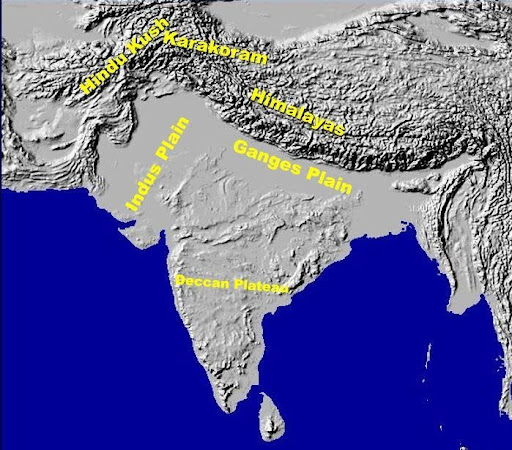

The realm of South Asia can be divided into three broad physiographic regions: the northern mountains, the southern plateaus, and between them is and a wide area of river lowlands between them. The northern mountains extend from the Himalayas in the east through the Karakoram Mountain range in the center to the Hindu Kush Mountain range in the northwest on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan (Figure 9.3). The Himalayas dominate the physical landscape in the northern region of South Asia. Mt. Everest is the tallest peak in the world, at 29,035 feet, but several other highest peaks in the world are also in the Himalayas, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush mountains (Figure 9.4). The Hindu Kush mountains extend through Kashmir and then meet up with the high ranges of the Karakoram-Himalayas. The Karakoram-Himalayas create a natural barrier between South Asia and China, with the kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan acting as buffer states with Tibet. The north-facing slopes of these ranges in Pakistan and Afghanistan are generally dry and barren due to the rain shadow effect; the southern slopes become green and forested in Swat, Kashmir, in the lower-lying elevations of Nepal, and even more green in the Arunachal Pradesh area of India. Farming in dry and barren mountainous valleys is possible by channeling glacial water to the valley floor (Figure 9.5).

The Southern Plateaus constitute peninsular India. The largest of these plateaus is Deccan Plateau, which is a massive igneous tableland that was formed when India split apart from Pangaea. The plateau has an eastward tilt, which makes most of the rivers drain into the Bay of Bengal. The Central Indian Plateau and Chota Nagpur Plateau are the two other plateaus that lie to the north of Deccan Plateau in the central parts of India. The Central Indian Plateau is to the west, and Chota Nagpur Plateau is to the east. Chota Nagpur Plateau receives ample monsoon-induced annual rainfall, an average of about 52 inches of rain per year. Chota Nagpur Plateau has a tiger reserve and is also a refuge for Asian elephants.

The zone of fluvial lowlands extends eastward from the lower Indus Valley in Pakistan through the wide Indo Gangetic Plain and then on across the great Ganges and Brahmaputra delta in Bangladesh. In the east, this physiographic region is called the North Indian Plain. To the west is the lowland of the Indus River, which originates in Tibet, travels southward, and along the way receives its major tributaries from the area known as Punjab (“Land of Five Rivers”) to the east. Descending eastward and westward from the Deccan Plateau toward the narrow coastal plains below are the eastern Ghats and western Ghats (“steps”). These ghats receive ample precipitation during the summer monsoon season; as a result, they are regarded as one of the most productive and populated areas of southern India.

The landmass of South Asia was formed as the result of the collision between the Indian Plate in the south and the Eurasian Plate in the north about seventy million years ago. The collision of these two continental plates gave rise to the highest mountain ranges in the world. Most of the South Asian landmass was formed from the land in the original Indian Plate. Mountain-building processes in the region are continuing. Pressure from tectonic action against the plates causes the Himalayas to rise in elevation by as much as one to five millimeters per year. Destructive earthquakes and tremors are frequent in this seismically active realm, particularly in the northern area.

Three mighty rivers cross South Asia, all originating from the Himalayas. The Indus River starts in Tibet and flows through the center of Pakistan and drains into the Arabian Sea, near Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city. The Ganges River flows eastward through northern India, creating a core region of the country known as the Ganges Plain. The mighty Indus and Ganges Rivers together form the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the largest productive region of this realm. The Brahmaputra River flows through Tibet and then enters India from the east, where it meets up with the Ganges in Bangladesh to flow into the Bay of Bengal.

The coastal regions in southern Bangladesh also have low elevations. When the seasonal reversal of winds called the monsoon arrives every year, there is heavy flooding, and its effect on the infrastructure of the region is disastrous. The extensive Thar Desert in western India and parts of Pakistan, on the other hand, does not receive monsoon rains. In fact, much of southwest Pakistan—a region called Balochistan—is dry, with desert conditions.

The Monsoon

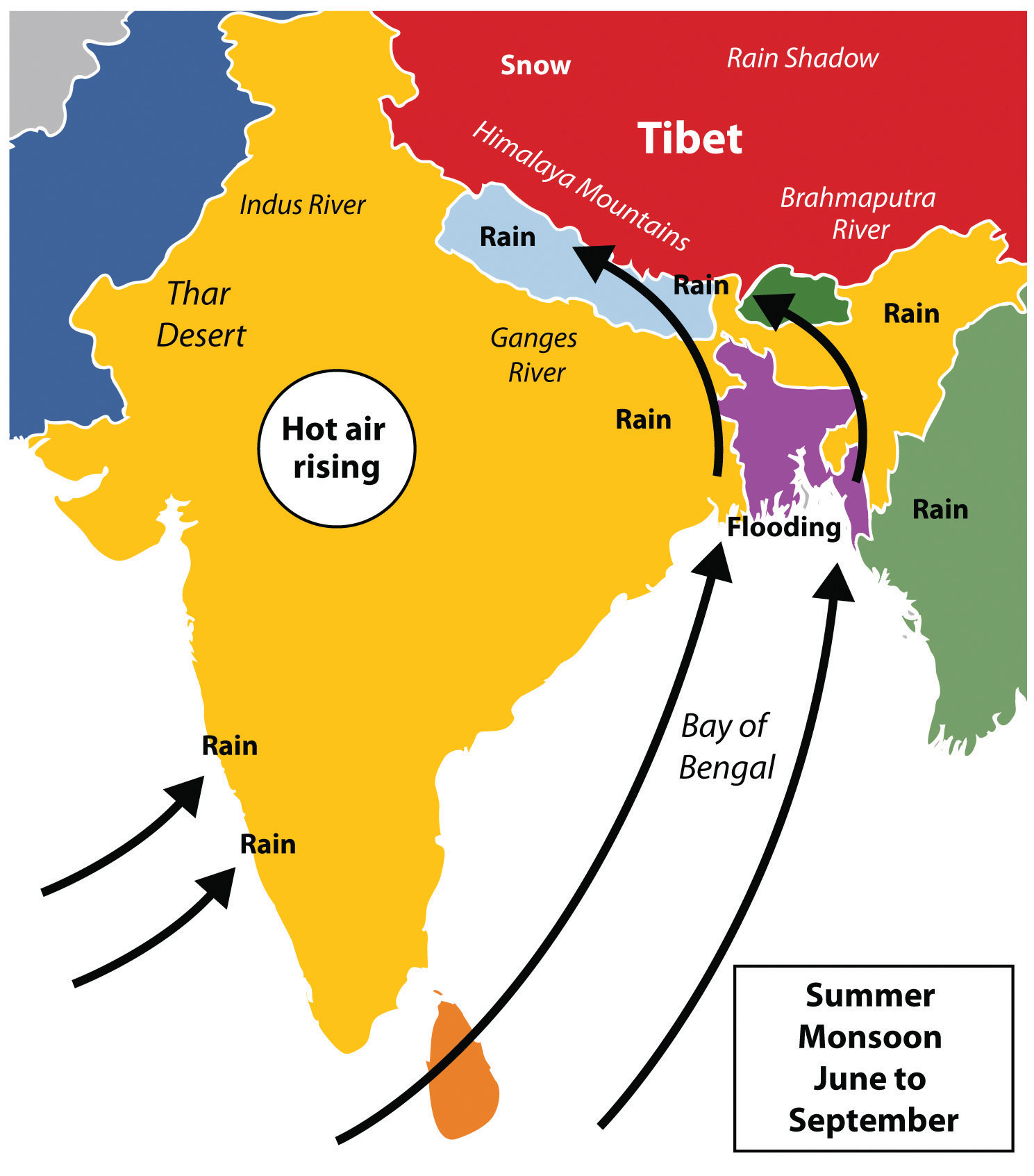

A monsoon is a seasonal reversal of winds that is associated with heavy rains. The summer monsoon rains—usually falling between June and September—feed the rivers and streams of South Asia and provide the water needed for agricultural production. In the summer, the continent heats up, with the Thar Desert fueling the system. The rising hot air creates a vacuum that pulls in warm moist air from the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. This action shifts moisture-laden clouds over the land, where the water is precipitated out in the form of rain.

The monsoon rains bring moisture to South Asia right up to the southern slopes of the Himalayas. As moisture-laden clouds rise in elevation in the mountains, the water vapor condenses in the form of rain or snow and feeds the streams and basins that flow into the Brahmaputra, Ganges, and Indus, the three major rivers of South Asia. The Western Ghats creates a similar system in the south along the west coast of India. Parts of Bangladesh and eastern India receive as much as six feet of rain during the monsoon season. Some areas impacted by monsoon rains experience severe flooding. The worst-hit places are along the coast of the Bay of Bengal, such as in Bangladesh. There is less danger of flooding in western India and Pakistan, because by the time the rain clouds have moved across the Subcontinent, they have lost their moisture. Desert conditions are evident in the western and northern edges of the region, near the Pakistan border in the great Thar Desert. On average, fewer than ten inches of rain falls per year in this massive desert. On the northern rim of the region, the height of the Himalayas restricts the uplifting of moist warm monsoon air over the mountain range. The Himalayas act as a precipitation barrier and create an intense rain shadow effect for the northern areas of Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tibet, and Western China. The monsoon is responsible for much of the summer rainfall in South Asia.

By October, the system has run its course, and the monsoon season is generally over. In the winter, the cold, dry air above the Asian continent blows to the south, and the winter monsoon is characterized by cool, dry winds coming from the north. South Asia experiences a dry season during the winter months. A similar pattern of rainy summer season and dry winter season is found in other parts of the world, such as southern China and some of Southeast Asia. A final note about the monsoons: small parts of South Asia, such as Sri Lanka and southeastern India, experience a rainy winter monsoon as well as a rainy summer monsoon. In their case, the winter monsoon winds that come down from the north have a chance to pick up moisture from the Bay of Bengal before depositing it on their shores.

Early Civilizations

The subcontinent of South Asia has a long history of human occupation and civilization. In its fertile river valleys, human settlements emerged and flourished into thriving urban centers and advanced civilizations. The earliest civilization, known as the Indus Valley Civilization, emerged along the banks of the Indus River in the northern region of the Indian Subcontinent (present-day Pakistan) between C. 7000 and C. 600 BCE. This Bronze Age civilization started as a series of small villages that became linked into a wider regional network. The two best-known cities of this culture are Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, located in the Sindh province of present-day Pakistan. The excavation of the Harappa site in late 1820 provided the very first evidence of the Indus Valley Civilization. Almost a century later, in the 1920s, excavations on the site of Mohenjo-Daro began. The excavation of these cities revealed a sophisticated urban infrastructure. The cities were planned with major streets built on a grid system. Evidence of a network of underground water supply channels, a sewage network, and public baths was found as a result of excavation. Both cities are thought to have populations of between 40,000 and 50,000 people. The total population of the civilization is thought to have been upward of five million. This civilization had a homogeneous material culture. Its artifacts of pottery and metallurgy all had a very similar style that was spread over a vast land area, a fact that aided in the recognition of the expanse of the culture. Between C. 1900 and C. 1500 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilization began to decline for unknown reasons. Some scholars attribute the decline and ultimately the vanishing of this civilization to climate change including the shifting of the ancient course of the Indus River.

The northern plains of South Asia, which extend through the east-west trending Ganges River Valley over to the north-south trending Indus River Valley of present-day Pakistan, were fertile grounds for several empires that controlled the region throughout its long history of human occupation. After the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization C. 1500 BCE, various phases of Iron Age cultures emerged. Most of this Iron Age culture is defined by the presence of iron metallurgy and distinctive characteristics of ceramics found in the region.

The Mauryan Empire which existed between C. 321 BCE and 185 BCE, was one of the most powerful empires in ancient India. The Mauryan Empire was the first pan-Indian empire that covered most of the Indian subcontinent as well as parts of present-day Afghanistan and Iran. This empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya in C. 321 BCE. Chandragupta took advantage of the power vacuum left by Alexander’s death in 323 BCE and began to extend his rule to areas that had been disrupted by the expansion of Greek armies. The Mauryan Empire was prosperous and greatly expanded the region’s trade, agriculture, and economic activities. This empire created a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. One of the greatest emperors in the Mauryan dynasty was Ashoka the Great (C. 268–232 BCE.), who ruled over a long period of peace, political stability, and economic prosperity. He created hospitals and schools and renovated major road systems throughout the empire. Ashoka embraced Buddhism and played an important role in the advancement of this new religion throughout his vast empire. After Ashoka’s death, the empire began to shrink and break apart because of invasions and internal political instability. The last Mauryan emperor, Brihadratha, was assassinated in 185 BCE by his commander in chief, Pushyamitra, who founded the Shunga Dynasty, which ruled in central India for about a century.

Kingdoms and dynasties emerged and ruled in the Indian subcontinent during the centuries that followed, but none of them achieved power and political influence comparable to the Mauryan Empire. Many of them failed to consolidate their power over most or all of the Indian Subcontinent. It was not until the 16th century when another powerful empire known as the Mughal Empire, was established in 1526 CE. At its peak during the 17th century, the Mughals ruled over most of present-day India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and parts of Afghanistan.

The arrival of Islam in the Indian Subcontinent started when in C. 712 CE, Muhammad Bin Qasim, a young Arab general of the Arab Umayyad dynasty attacked and sacked the coastal port city of Debal in southern Sind near the modern city of Karachi in Pakistan. Militarily, this is not considered a significant event because it did not lead to further advancements of Muslim armies in the Indian Subcontinent. The loss of Umayyad rule forced Mouhammad Bin Qasim to return to Damascus, Syria (then Umayyad seat of power). However, it started the process of diffusion of the Islamic faith in South Asia. Starting in the late 12th century, a campaign of invasions by different Afghan Muslim Tribes started, which culminated with the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 CE. This was the beginning of the formal period of Islamic rule in the Indian Subcontinent that lasted until 1857 CE when India formally became the British Indian Empire. We can distinguish the following two periods of Islamic rule in the Indian Subcontinent.

- The Delhi Sultanate (1206 CE – 1526 CE): Muslim dynasties that ruled mostly northern and northwestern parts of the Indian Subcontinent and made Delhi their capital are collectively referred to as the Delhi Sultanate. This period began with the Ghurid (“Ghori”) Dynasty, which originated from the Ghor region of present-day Afghanistan, and ended with the Lodi (“Lodhi”) Dynasty (1451 CE – 1526 CE), which also originated from eastern Afghanistan. Between these two dynasties, several other dynasties ruled over the Delhi Sultanate sequentially. This period of Islamic rule in India differs from the period that followed it in three main ways. First and most importantly, none of the dynasties of this period were successful in consolidating their rule over all of the Indian Subcontinent. Their rule mostly spanned northern India, including the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and areas of present-day central and northwestern Pakistan. Second, rulers of all dynasties of this period considered the “Caliph” of that time to be their spiritual and temporal leader, and it is for this very reason that instead of referring to themselves as “king,” they all preferred to use the title of “sultan.” Finally, the Delhi Sultanate was fundamentally an Afghan sultanate, as the majority of the rulers were of Afghan descent.

- The Mughal Empire (1526 CE – 1857 CE): The Mughal Empire was founded by Zaheer-ud-Din Muhammad Babar, a leader of Mongol descent from central Asia. The long period of the Delhi Sultanate came to an end in 1526 CE, when Babar defeated Ibrahim Lodhi, the last of the Afghan Lodhi Sultans at the First Battle of Panipat (a famous medieval battleground located north of Delhi in India). Artillery was used for the first time in a battle on Indian soil. The sound of gunpowder exploding caused panic among the large number of battle elephants placed at the front of the Afghan forces. Panic-stricken elephants trampled over foot soldiers, thus tilting the outcome of the battle in Babar’s favor. Babar, after taking over the throne of Delhi, abolished the title of ‘sultan’ and called himself the emperor of India. The classic period of this empire began in 1556 with Mughal Emperor Akbar the Great and ended in 1707 with the death of the last great Mughal ruler Aurangzeb. Many of the monuments we associate with India, including the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort in Lahore, and Delhi, were built during the classical period. After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire started a slow and steady decline because of bad governance and rising European interference and influence in Mughal affairs. By the 19th century, the vast tracts of the Mughal Empire were under the control of a British trading company known as the British East India Company. Technically, they were ruling as agents of the Mughal Empire, but they were in practice exercising complete power. In 1857, after an unsuccessful uprising by the Indian population against the British influence in India, Britain assumed direct control of India and abolished the East India Company. The last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II was exiled to Burma (Myanmar), and Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India. India became the jewel of the British Empire. The end of the British Indian Empire occurred at midnight on August 14, 1947, when not only did 200 years of British rule in India end but also India was partitioned into two separate countries—a Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-dominated republic of India.

Colonialism in South Asia

The force of colonialism was felt around the world, including in South Asia. South Asia provides an excellent example of colonialism’s role in establishing most of the current political borders in the world. From the 16th century onward, Europeans began to arrive in South Asia to conduct trade. The British East India Company was chartered in 1600 to trade in Asia and India. They established fortified trading posts along the coast of India. They recruited local sepoys to guard their interests and traded in spices, silk, cotton, and other goods. Later, to take advantage of local conflicts and political instability, European powers began to establish colonies and raised their own armies of local sepoys. Although Britain was the greatest European power with colonial ambitions in the Indian Subcontinent, there were several others, including the French and the Portuguese. In the end, Britain proved to be the most successful. In the Indian Subcontinent, We can distinguish two periods of British colonial rule that spanned over 200 years. First is the British East India Company rule from 1757 CE to 1857 CE. During this period of “company rule,” even though the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II was still sovereign, for all practical purposes, he had become a figurehead without any authority and was even dependent on the “company’s” stipend for a living. The East India Company enjoyed virtually full control over internal and external affairs of the Mughal Empire. The second period of British presence in the Indian Subcontinent started in 1857 and ended in 1947. The events associated with the last battle for freedom (also known as “Mutiny” by British historians) by the locals to get rid of the East India Company’s rule led to the abolishing of the East India Company and the end of whatever was left of the Mughal Empire. The British crown took control of India, and India became the British Indian Empire, which lasted until August 1947.

The 200 years of British colonial rule in India deeply impacted the fabric of the local society. The biggest impact of foreign European rule was on religious tolerance and communal harmony that had existed between diverse populations of India for more than 1000 years. By the first quarter of the 20th century, Indian society had become polarized along ethnic, religious, and linguistic lines. This coupled with the fact that WWII had badly weakened the British Empire, and the crown was no longer able to maintain such a vast colony, ultimately resulted in the partitioning of the Indian subcontinent on cultural and religious lines. West Pakistan was carved out of Muslim-majority western India; East Pakistan was carved out of Muslim-majority eastern India (Bengal). However, the new borders separating Hindu and Muslim majorities ran through population groups, and some of the population now found itself on the wrong side of the border. The partition grew into a tragic civil war, as Hindus and Muslims struggled to migrate to their country of choice. More than one million people died in the civil war, a war that is still referred to in today’s political dialogue between Pakistan and India. The Sikhs, who are indigenous to the Punjab region in the middle, also suffered greatly. Some people decided not to migrate, which explains why India has the largest Muslim population of any non-Muslim state. The boundary commission, the body established by the British government to demarcate international borders between India and Pakistan and between Pakistan and Afghanistan, often split culturally homogenous populations and tribes into two countries, which has created all sorts of border issues between countries in the region.

When Pakistan was first created in 1947, its disjunct western and eastern portions operated under the same government despite having no common border, being over nine hundred miles apart, and being populated by people with no ethnic and linguistic similarities. Mohammad Ali Jinah, the founder of Pakistan, declared Urdu as the national language even though, other than Urdu-speaking migrants from India who had settled in West Pakistan, a very small percentage of the population of West Pakistan spoke Urdu as their mother tongue. People of East Pakistan spoke Bengali and also were in the majority, and therefore they wanted Bengali to be the national language of a united Pakistan, but Jinah did not agree to it. The resentment over language ultimately led to East Pakistan’s separation from Pakistan and becoming a new country of Bangladesh in 1971. The name Bangladesh is based on the Bengali ethnicity and language of the people who live there.

Language is probably one of the more pervasive ways that Europeans affected South Asia. In modern-day India and Pakistan, English is the language of choice in secondary education (English-medium schools). It is often the language used by the government and military. Unlike many other Asian countries, much of the signage and advertising in Pakistan and India is in English, even in rural areas. Educated people switch back and forth, using English words or entire English sentences during conversations in their native tongue.

The sport of cricket, a legacy of British colonial rulers, is an important cultural and national sport in all South Asian countries. The constant conflict between the nations of India and Pakistan is reflected in the intense rivalry between their national cricket teams. The Cricket World Cup is held every four years and is awarded by the International Cricket Council. South Asian countries have won the Cricket World Cup three times: India in 1983, Pakistan in 1992 (former Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan was the captain of the team), and Sri Lanka in 1996.

Population in South Asia

South Asia has three of the ten most populous countries in the world. India is the second largest in the world, and Pakistan and Bangladesh are numbers five and six, respectively. Large populations are a product of large family sizes and a high fertility rate. The rural population of South Asia has traditionally had large families. Religious traditions do not necessarily support anything other than a high fertility rate. On the other hand, the least densely populated country in South Asia is the Kingdom of Bhutan. Bhutan has a population density of only fifty people per square mile. Bhutan is mountainous with little arable land. More than a third of the people in Bhutan live in an urban setting. Population overgrowth is a serious concern across the realm. An increase in population requires additional natural resources, energy, and food production, all of which are in short supply in many areas.

| Rank | Country name | Population in millions | Total population density | Physiologic density | Fertility rate | Population growth rate (%) | Doubling time in years† | Percentage urban | Gross domestic product per capita ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 1,336 | 361 | 2,405 | 1.54 | 0.49 | 143 | 47 | 7,600 |

| 2 | India* | 1,189 | 937 | 1,912 | 2.62 | 1.34 | 52 | 30 | 3,500 |

| 3 | United States | 313 | 84 | 468 | 2.06 | 0.96 | 73 | 82 | 47,200 |

| 4 | Indonesia | 245 | 331 | 3,013 | 2.25 | 1.07 | 65 | 44 | 4,200 |

| 5 | Brazil | 203 | 62 | 884 | 2.18 | 1.13 | 62 | 87 | 10,800 |

| 6 | Pakistan* | 187 | 604 | 2,414 | 3.17 | 1.57 | 45 | 36 | 2,500 |

| 7 | Bangladesh* | 158 | 2,852 | 5,186 | 2.60 | 1.57 | 45 | 28 | 1,700 |

| 8 | Nigeria | 155 | 435 | 1,319 | 4.73 | 1.94 | 36 | 50 | 2,500 |

| 9 | Russia | 138 | 21 | 301 | 1.42 | −0.47 | 73 | 15,900 | |

| 10 | Japan | 126 | 867 | 7,225 | 1.21 | −0.28 | 67 | 34,000 | |

| 11 | Mexico | 113 | 149 | 1,149 | 2.29 | 1.10 | 64 | 78 | 13,900 |

| 41 | Nepal* | 29 | 525 | 3,379 | 2.47 | 1.59 | 44 | 19 | 1,200 |

| 57 | Sri Lanka* | 21 | 862 | 6,001 | 2.2 | 0.93 | 75 | 14 | 5,000 |

| 165 | Bhutan* | 0.700 | 50 | 1,697 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 58 | 35 | 5,500 |

| 176 | Maldives* | 0.400 | 3,438 | 26,194 | 1.81 | −0.15 | 40 | 6,900 | |

| * Countries noted with an asterisk are part of South Asia | |||||||||

| † Empty cell indicates a negative population doubling time. | |||||||||

Table 9.1 Demographics of South Asia and the World’s Most Populous Countries.

South Asia’s growing population has placed exceedingly high demands on agricultural production. The amount of area available for food production divided by the population may be a more helpful indicator of population distribution than total population density. For example, large portions of Pakistan are deserts and mountains that do not provide arable land for food production. India has the Thar Desert and the northern mountains. Nepal has the Himalayas. The small country of the Maldives, with its many islands, has almost no arable land. The number of people per square mile of arable land, which is called the physiologic density, can be an important indicator of a country’s status. Total population densities are high in South Asia, but the physiologic densities are even more astounding. In Bangladesh, for example, more than five thousand people depend on every square mile of arable land. In Sri Lanka, the physiologic density reaches to more than 6,000 people per square mile, and in Pakistan, it is more than 2,400. The data are averages, which indicates that the population density in the fertile river valleys and the agricultural lowlands might be even higher.

The population of South Asia is relatively young. In Pakistan, about 35 percent of the population is under the age of fifteen, while about 30 percent of India’s almost 1.4 billion people are under the age of fifteen. Many of these young people live in rural areas, as most of the people of South Asia work in agriculture and live a subsistence lifestyle. As the population increases, the cities are swelling to accompany the growth in the urban population and the large influx of migrants arriving from rural areas. Rural-to-urban shift is extremely high in South Asia and will continue to fuel the expansion of the urban centers into some of the largest cities on the planet. The rural-to-urban shift that is occurring in South Asia also coincides with an increase in the region’s interaction with the global economy.

The South Asian countries are transitioning through the five stages of the index of economic development. The more rural agricultural regions are in the lower stages of the index. The realm experienced rapid population growth during the latter half of the twentieth century. As death rates declined and family size remained high, the population swiftly increased. India, for example, grew from fewer than four hundred million in 1950 to more than one billion at the turn of the century. The more urbanized areas are transitioning into stage 3 of the index and experiencing significant rural-to-urban shift. Large cities such as Mumbai (Bombay) have sectors that are in the latter stages of the index because of their urbanized workforce and higher incomes. Family size is decreasing in the more urbanized areas and in the realm as a whole, and demographers predict that eventually the population will stabilize.

At the current rates of population growth, the population of South Asia will double in about fifty years. Doubling the population of Bangladesh would be the equivalent of having the entire 2011 population of the United States (more than 313 million people) all living within the borders of the US state of Wisconsin. The general rule of calculating doubling time for a population is to take the number seventy and divide it by the population growth rate. For Bangladesh, the doubling time would be 70 ÷ 1.57 = 45 years. The doubling time for a population can help determine the economic prospects of a country or region. South Asia is coming under an increased burden of population growth. If India continues at its current rate of population increase, it will double its population in fifty-two years, to approximately 2.4 billion. Because the region’s rate of growth has been gradually in decline, this doubling time is unlikely. However, without continued attention to how societies address family planning and birth control, South Asia will likely face serious resource shortages in the future.

Key Takeaways

- All the South Asian countries border India by either a physical or a marine boundary. The Himalayas form a natural boundary between South Asia and East Asia (China). The realm is surrounded by deserts, the Indian Ocean, and the high Himalayan ranges.

- The summer monsoon arrives in South Asia in late May or early June and subsides by early October. The rains that accompany the monsoon account for most of the rainfall in South Asia. Water is a primary resource, and the larger river systems are home to large populations.

- The Indus River Valley was a location of early human civilization. The large empires of the realm gave way to European colonialism. The British dominated the realm for ninety years from 1857 to 1947 and established the main boundaries of the realm.

- Population growth is a major concern for South Asia. The already enormous populations of South Asia continue to increase, challenging the economic systems and depleting natural resources at an unsustainable rate.

Discussion and Study Questions

- Why are the Himalayan Mountains continuing to increase in elevation? Which of the countries of South Asia border the Himalayas?

- What are the three major rivers of South Asia? Where do they start and what bodies of water do they flow into? Why have these river basins been such an important part of the early civilizations of the realm and why are they core population areas today?

- Why does the monsoon usually arrive in late May or early June? What is the main precipitation pattern that accompanies the monsoon? Why is the monsoon a major source of support for South Asia’s large population?

- What changes did British colonialism bring to South Asia? When did the British control South Asia? Why do you think the British lost control when they did?

- Why is the high population growth rate a serious concern for South Asian countries? What can these countries do to address the high population growth rate?

- How can Pakistan have a higher fertility rate than Bangladesh but still have the same growth rate and doubling time?

- Why would the country of the Maldives be concerned about climate change?

- How would you assess the status of each country with regard to the index of economic development?

- What are the three dominant religions of the realm? How did religion play a role in establishing the realms’ borders? What happened to East Pakistan?

- How can the principle of doubling time be used to assess a country’s future potential? What is the general formula to calculate a population’s doubling time?

Geography Exercises

Identify the following key places on a map:

- Arabian Sea

- Baluchistan

- Bay of Bengal

- Brahmaputra River

- Central Indian Plateau

- Chota-Nagpur Plateau

- Deccan Plateau

- Eastern Ghats

- Ganges River

- Himalayas

- Indian Ocean

- Indus River

- Kashmir

- Mt. Everest

- Punjab

- Thar Desert

- Western Ghats