2.5 The Classical School of Criminological Theory

Brandon Hamann

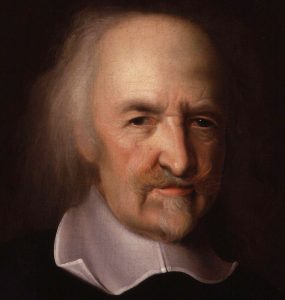

During the Middle Ages, people began to question the justification for how they were being ruled by their governments (Fedorek, 2019). In the mid-17th century Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), a British philosopher, wrote in his seminal piece Leviathan (1651) that people were rational and were entitled to such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the right to self-government. In the case of punishment, according to Hobbes (1651), judges were not bound by another’s sentencing prescription simply because there was precedence to do so (Hobbes, 1965). This social contract thinking would later be a building block for the modern American Criminal Justice System.

One of the first “Criminologists” wasn’t even one. Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), an Italian philosopher, economist, and politician, is considered to be the “Father of Criminology.” He authored a book titled An Essay on Crimes and Punishment in 1764 which laid the foundation for what came to be called the Classical School of Criminological Theory. In the book, Beccaria theorized that crime occurs when the benefits outweigh the costs—when people pursue self-interest in the absence of effective punishments, and that crime is a free-willed, rational choice. Beccaria also developed the concept of proportionality, which states that in order for a punishment to be effective, it must fit the crime that it is intended to deter from repeating (di Beccaria & Voltaire, 1872).

crime is a rational choice made when the benefits outweigh the costs.

punishment should fit the crime it is intended to deter from repeating.