2.7 The Chicago School of Criminological Theory

Brandon Hamann

The Biological Positivists looked at criminality through the lens of scientific experimentation, attempting to explain causation through physical traits. The Psychological Positivists tried to explain criminality as a product of mental illness and looked at individual and group personality traits as possible causes. The Chicago School, however, took things to a different level. They saw criminal behavior as a product of one’s environment, developing the concept of human ecology – the study of the relationship between humans and their environment. The Chicago School was so named because the theorists who produced the groundbreaking research into how humans interacted with their surroundings and how that interaction affected behavior came from the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s (Fedorek, 2019).

Robert E. Park (1864-1944), an American urban sociologist, spent his professional career studying human behavior as it pertained to human ecology, race relations, assimilation, migratory patterns, and social structure. Along with his colleagues, noted sociologists Ernest W. Burgess and R. D. McKenzie, Robert Park published the book The City (1925), which conceptualized a city much like a living organism, with interactions between humans and their natural environments acting in both a shared and conflicting manner depending on where a group lived within the city.

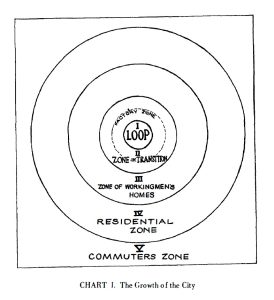

It was Burgess, however, who proposed the Concentric Zone Theory, which stated that a city’s design was conducive to criminal behavior within its “Zone of Transition” between the areas where people worked and where they lived (Burgess, 1925). In simpler terms, a city could be seen much like a target board, with multiple concentric circles surrounding a central hub (see Figure 2.8). Each inner and outer circle was specific to its municipal function (manufacturing, city business, residential, etc.).

Two students of Burgess and Park at the University of Chicago expanded on the concept of the Concentric Zone Model and developed their own theory. Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) noticed that within the different zones of transition, there were inequalities between them. Some had infrastructure that was in disrepair, some had differing demographics, and some had socioeconomic differences (Fedorek, 2019). What all this meant was that not every residential zone was the same, had the same type of people living in them, or had the same level of income, education, or employment opportunities. Those zones that were more educated, had higher levels of income, and fewer buildings in bad shape, were more organized than those zones with less educated people of color, higher unemployment, lower income, and more “broken windows” (more on this later).

What does all this have to do with crime? According to Shaw and McKay, a great deal. If one community is experiencing a high level of “social disorganization” due to inequalities experienced because of low employment, or low education opportunities, or even the inability to communicate within its own neighborhoods because the population is unable to understand each other, then there can theoretically be a higher chance for criminality within that specific zone of transition. Likewise, the opposite is also theoretically true: If a zone of transition is highly organized, the population is cohesive and stable with higher levels of income, education, and a low unemployment rate, the chances of there being a high crime rate is relatively low.

Dr. Edwin Sutherland (1883-1950) was an American Sociologist considered to be one of the most influential criminologists of his time. He is credited with the development and definition of Differential Association Theory of Criminality and coined the term “White-Collar Crime” in 1939. Dr. Sutherland earned his PhD in Sociology from the University of Chicago in 1913 and went on to establish the Bloomington School of Criminology at Indiana University. According to Dr. Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory, criminality was a learned behavior, commonly brought on by groups of individuals who had splintered from the main group and had deviated in their behaviors from the accepted norms (see Section 2.10.3 for further analysis). Sutherland also was instrumental in combating the established notion that criminal behavior was relegated to only the poor and lower class of society. He famously theorized that the upper classes were more than capable of criminal behavior and were not immune to the deviance of criminality just because of their social status. Furthermore, Dr. Sutherland’s “White-Collar Crime” theory purported that businesses frequently engaged in criminal activity for the benefit of their practice as an expression of their business (Sutherland, 1940).

the study of the relationship between humans and their environment.