7.4 Incapacitation

David Carter; Kate McLean; and Michelle Holcomb

Incapacitation

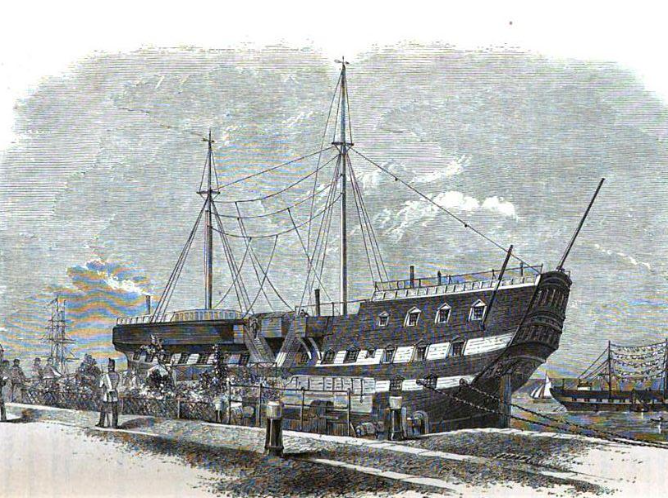

Rooted in the concept of “banishment,” incapacitation is the removal of an individual from society, for a set amount of time, so that they cannot commit crimes (in society) during that period. In British history, this often occurred on Hulks. Hulks were large ships that carried convicted individuals off to faraway lands. The point was to prevent them from committing crimes in their original community.

Beginning in the 1950s, punishment became much more of a politically relevant topic in the United States. Lawmakers, justice officials, and others began to campaign on the basis of their “toughness” on crime, using the public’s fear of crime and criminals to benefit their agendas. One way that such officials could show that they were tough on crime was through their support for long prison sentences. Such policies might be considered as collective incapacitation, or the incarceration of large groups of individuals in order to restrict their ability to commit crimes.

In fact, the 20th century saw a nearly continual increase in the use of prison – and long prison sentences – to punish offenders. For this reason, the U.S. experienced a rapid growth in state and federal prison populations over the past 40 years – what we commonly refer to now as “mass incarceration.” This “politicization of punishment” increased the overall imprisonment rate in two ways. First, by limiting the sentencing discretion of judges, the country as a whole has effectively gotten tougher on crime. Specifically, more people were, and are being, sentenced to prison that may have otherwise gone to specialized probation or community-sanctioned alternatives. Second, the legal sentences and sentencing ranges passed by legislators (and endorsed by prosecutors in their charging decisions) have led to harsher and lengthier punishments for certain crimes. Offenders are being sent to prison for longer sentences, which has caused the intake-to-release ratio to increase, causing enormous buildups of the prison population.

The incapacitative ideology followed this design for several decades. In the early 1990s, policies were implemented that targeted individual offenders more specifically through habitual offender or “three strikes” policies (discussed in the last part). Such policies incarcerate individuals for greater lengths of time if they have prior or concurrent offenses. These policies reflect a philosophy of selective incapacitation.

Evidence on the effectiveness of selective and collective incapacitation is mixed, at best. Policymakers may promote their ideals through examples of locking certain offenders away in order to help calm the fear of crime. Researchers, however, have shown that there are minimal savings at best, stating that these goals do not achieve the intended results as previously suggested (Blokland, 2007). Future styles of selective incapacitation have evolved to include tighter crime control strategies that incorporate variated sentencing strategies to selectively incapacitate higher-rate offenders. Others opt for tougher parole procedures to retain more harmful offenders longer.

Overall, we are still left with the same questions: Does it work? And, at what cost? Do these lengthier punishments for particular crimes have an effect by selectively incapacitating hardened criminals? Are there other methods that are more effective, and less costly, than the ones already in practice? This takes us to the last of the four main punishment ideologies: rehabilitation.

Reducing the offender's ability to commit crimes

the incarceration of large groups of individuals in order to restrict their ability to commit crimes.