Chapter 7: Adolescence

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Be familiar with the characteristics of adolescent physical development

- Be familiar with the characteristics of adolescent cognitive development

- Be familiar with the factors associated with adolescent psychosocial development

- Understand how culture plays a role in adolescent development

- Understand how social media plays a role in adolescent development

- Be familiar with the theoretical development stages that take place during adolescence

- Be familiar with the common factors that are associated with academic achievement for adolescents and the potential barriers they face to being successful

- Be familiar with adolescents’ relationships with their families, peers, and others

Louisiana Snapshot

What’s It like Growing up in Louisiana?

In this video, teens from Lafayette share their experiences of growing up in Southwest Louisiana.

Growing Up in Louisiana (YouTube Video).

Are you feeling inspired to share? Create a YouTube video of your own and post it using #GrowingUpInLouisiana.

How Do You Define Adolescence?

Adolescence is a stage of life that begins with puberty and ends with the transition to adulthood, usually between the ages of 10 and 20. This phase has changed over time due to recent findings that show individuals start puberty earlier and transition into adulthood later than in the past.

During adolescence, girls and boys undergo rapid physical, cognitive, and psychosocial growth, affecting how they perceive the world, make decisions, and interact with it. Puberty is triggered by hormones, leading to physical changes in the body. Adolescents also experience cognitive changes, including abstract thinking and increased sensation-seeking and reward motivation, which can precede cognitive control and lead to risky behavior.

Adolescents become more autonomous during this period, and their relationship with their parents undergoes significant transformations. They start making independent decisions that align with their values and goals instead of being coerced by external forces. Parenting aspects such as distal monitoring and psychological control become more relevant at this stage. Peer relationships are also crucial sources of support and companionship for adolescents, though they can sometimes promote problem behaviors. Adolescents’ same-sex peer groups evolve into mixed-sex peer groups, and their romantic relationships generally emerge from these groups.

Identity formation is another critical aspect of adolescence, as young individuals explore and commit to different roles and ideological positions. Nationality, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religious background, sexual orientation, and genetic factors can all shape how adolescents behave and how others respond to them. These are sources of diversity in adolescence.

Physical Changes in Adolescence

Specific physical changes mark the beginning of adolescence. Such changes include a sudden increase in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes, such as pimples. While males experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voices, females experience breast development and begin menstruating. These changes are primarily attributed to hormone changes during puberty, with increased testosterone and estrogen for females. In the United States, puberty typically begins around age 10-11 years for females and 11-12 years for males on average. Although the sequence of physical changes is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary significantly. Research has shown that African-American and Hispanic-American females experience puberty sooner compared to White females (Bleil, Booth-LaForce & Benner, 2017). Puberty’s timing is different for each person and is primarily influenced by heredity, but environmental factors such as diet and exercise also exert some influence.

Hormonal Changes

Several physical changes occur during puberty. The first phase, adrenarche, is between ages 6 and 8; the second phase, gonadarche, begins several years later with the maturing of the adrenal glands and sex glands. Also, during this time, primary and secondary sexual characteristics develop and mature. Primary sexual characteristics are organs precisely needed for reproduction, like the uterus and ovaries in females and testes in males. Secondary sexual characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs, such as the development of breasts and hips in girls and facial hair and deepening voices in boys. Girls experience menarche, the beginning of menstrual periods, usually around 12–13 years old, and boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old (Crooks & Baur, 2007).

During puberty, both sexes experience a rapid gain in height (i.e., growth spurt). For girls, this begins between 8 and 13 years old, with adult height reaching between 10 and 16 years old. Boys start their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old, and reach their adult height between 13 and 17. Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence height (Dolgin, 2011).

Because rates of physical development vary so widely among teenagers, puberty can be a source of pride or embarrassment. Early-maturing boys are more muscular, taller, and more athletic than their later-developing peers. They are usually more popular, confident, and independent but also at a greater risk for substance abuse and early sexual activity (Weir, 2001). Early-maturing girls may be teased or overtly admired, which can cause them to feel self-conscious about their developing bodies. These girls are at a higher risk for depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010). Late-blooming boys and girls (i.e., they develop more slowly than their peers) may feel self-conscious about their lack of physical development. Negative feelings are particularly problematic for late-maturing boys, who are at a higher risk for depression and conflict with their parents (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010). They are likelier to be bullied (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010).

Racial Difference in Puberty

On average, racial differences are noted, with Asian-American females developing last, while African-American females tend to enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic females start puberty the second earliest, while European-American females tend to rank third in their age of beginning puberty. Although African-American females are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American females (Weir, 2016).

Nutrition and Puberty

Nutrition is one of the most critical factors affecting pubertal development. It is important to maintain a balanced and healthy diet throughout all stages of growth, including infancy, childhood, and puberty, in order to support proper growth and normal pubertal development. Research indicates that overweight or obese children are more likely to experience early puberty. Some studies suggest that obesity can hasten the onset of puberty in girls and delay it in boys. Additionally, nutrition has an impact on the progression of puberty (Soliman, De Sanctis & Elalaily, 2014).

What Types of Cognitive Development Are Experienced during Adolescence?

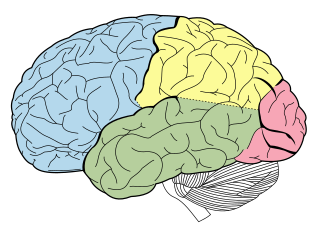

Brain Development

The adolescent brain continues to develop until puberty. During this time, brain cells in the frontal region continue to grow. This may explain why teenagers engage in more risky behavior and have emotional outbursts. The frontal lobes of their brains, responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, are still maturing into early adulthood. This information was presented in a study by Casey, Tottenham, Liston, and Durston, 2005.

The brain continues to grow until the early 20s. During this stage, the development of the frontal lobe is crucial. Adolescents develop more complex thinking abilities, which some researchers attribute to processing speed and efficiency improvements rather than increased mental capacity. This means they get better at existing skills rather than developing new ones. Teenagers move beyond concrete thinking and become capable of abstract thought. Piaget refers to this stage as formal operational thought. They can consider multiple points of view, imagine hypothetical situations, debate ideas and opinions, and form new ideas. Adolescents may also question authority or challenge established societal norms.

In addition, cognitive empathy, also known as the theory of mind, is the ability to take the perspective of others and feel concerned for them. It is crucial to social problem-solving and conflict avoidance. Levels of cognitive empathy tend to increase during adolescence, specifically around the ages of 13 for girls and 15 for boys. According to a study, teens who have supportive fathers with whom they can discuss their worries are better able to take the perspective of others.

Watch It

Dr. Dan Siegel explains brain development during adolescence.

What are the Psychosocial Experiences during Adolescence?

During adolescence, individuals go through a process of better understanding themselves in relation to others. Erikson described the challenge of adolescence as an identity crisis, where adolescents struggle to determine their sense of self and their place in society. They ask themselves, “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Some teenagers conform to their parent’s expectations, while others develop identities that may differ from their parents but align with their peers. Adolescents often place great importance on their relationships with peers as they work to form their identities.

As teens work to establish their identities, they tend to pull away from their parents. However, research shows that most adolescents still have positive feelings towards their parents despite spending less time with them. Studies have found that strong, positive parent-child relationships are associated with better academic performance and fewer teen behavior problems (Smetana, 2011).

Contrary to popular belief, most teenagers do not experience significant strife with their parents. While some conflicts may arise, they are typically minor and centered around day-to-day issues such as homework, money, curfews, clothing, chores, and friends. As teenagers mature, these arguments tend to decrease.

Social Changes

Although peers tend to be more significant during adolescence, family relationships are also crucial. This period involves rediscovering the parent-child relationship as adolescents strive for independence and autonomy. As adolescents spend more time away from their parents and with peers, parental supervision and monitoring become more critical. Parental monitoring involves parents setting rules and knowing their adolescents’ friends, activities, and whereabouts, as well as adolescents’ willingness to communicate with their parents. Psychological control, which includes manipulating and intruding into adolescents’ emotional and cognitive world by invalidating their feelings and pressuring them to think in certain ways, is another aspect of parenting that becomes more relevant during adolescence and is linked to more problematic adolescent adjustment.

During adolescence, children usually start spending less time with their families and more time with their peers, often without adult supervision. Adolescents’ ideas about friendship shift from focusing on shared activities to intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings. Peer groups evolve from being primarily single-sex to mixed-sex, and members of the same group tend to have similar attitudes and behaviors, which can be attributed to homophily and influence. Studies show that peers significantly impact adolescent behavior, particularly with deviant peer contagion, where peers reinforce problem behavior by showing approval or laughing, thereby increasing the likelihood of future problem behavior (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011).

Peers, a group of people with similar interests, ages, backgrounds, or social status, can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead to riskier decisions and more problematic behavior than they would engage in alone or with their family, such as drinking, drug use, and criminal activities. On the other hand, peers are an essential source of social support and companionship during adolescence. Adolescents with positive peer relationships tend to be happier and better adjusted than those without such relationships.

Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. Unlike friendships and cliques, reciprocal dyadic relationships, or groups of individuals who interact frequently, crowds are more characterized by shared reputations or images than actual interactions. These crowds reflect different prototypic identities and are often linked to adolescents’ social status and their peers’ perceptions of their values and behaviors.

Romantic Relationships

During adolescence, romantic relationships typically first emerge. As same-sex peer groups from childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups, these relationships often form in that context (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000). Although adolescent romantic relationships are usually short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance to adolescents should not be underestimated. Adolescents tend to focus much of their time on these relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more closely tied to romantic relationships (or lack thereof) than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and emotional and behavioral adjustment are all influenced by romantic relationships.

In addition, adolescent romantic relationships are closely tied to their emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have typically focused on adolescents’ sexuality with concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality encompasses much more than these issues. For instance, during adolescence, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender start to perceive themselves as such (Russell, Clarke, & Clary, 2009). As a result, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents experiment with new behaviors and identities.

Behavioral and Psychological Adjustment

Identity Formation

Theories of adolescent development often center on the issue of identity formation. In Erikson’s (1968) developmental stages theory, identity formation was emphasized as the primary indicator of successful development during adolescence, contrasting with role confusion, which would indicate a failure to meet the task of adolescence. Identity formation is a multifaceted process in which individuals establish a clear and unique view of themselves and their identity. Marcia (1966) described identity formation during adolescence as involving decision points and commitments concerning ideologies (such as religion and politics) and occupations. He identified four identity statuses: foreclosure, identity diffusion, moratorium, and identity achievement. Foreclosure occurs when an individual commits to an identity without exploring options. Identity diffusion occurs when adolescents neither explore nor engage in any identities. A moratorium is a state in which adolescents actively explore options but have not made commitments yet. Identity achievement occurs when individuals explore different options and commit to an identity. Based on this work, other researchers have explored more specific aspects of identity. For example, Phinney (1989) proposed a model of ethnic identity development that included stages of unexplored ethnic identity, ethnic identity search, and achieved ethnic identity.

Watch It

This video examines Marcia’s identity development theory and relates the four identity statuses to college students figuring out their majors.

For a transcript: “James Marcia’s Adolescent Identity Development” (opens in new window).

Self-Concept and Self-Esteem

During adolescence, teenagers continue to develop their sense of self. They become capable of thinking more abstractly about themselves and their possibilities, which may explain why their self-concept becomes more differentiated during this time. However, teenagers often have a contradictory understanding of themselves. For example, they may see themselves as outgoing yet withdrawn, happy yet moody, or intelligent yet clueless. These contradictions can make them feel like a fraud, as their behavior changes depending on their relationship. They may wonder which version of themselves is the real one (Harter, 2012). Teenagers tend to emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than younger children as they become increasingly concerned about how others see them. They also add values and moral standards to their self-descriptions as they age (Harter, 2012). As self-concept differentiates, so do self-esteem and confidence in one’s worth, abilities, or morals. In addition to self-esteem’s academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions, teenagers also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships. Self-esteem often drops when children transition from one school setting to another, such as elementary school to middle school or junior high to high school (Ryan et al., 2013). However, these drops are usually temporary unless additional stressors exist, such as parental conflict or other family disruptions. Most teenagers’ self-esteem increases from mid to late adolescence, especially if they feel competent in their peer relationships, appearance, athletic, and other abilities (Birkeland et al., 2012).

Aggression and Antisocial Behaviors

Antisocial behaviors are actions that violate the rights of others. Several significant theories point towards adolescence as a crucial period for developing these behaviors. Patterson’s (1982) model of early versus late starters distinguishes between two groups of individuals. Early starters begin to show antisocial behavior during childhood, while late starters show these behaviors during adolescence. According to the theory, early starters are at a higher risk of continuing antisocial behavior into adulthood. Late starters, on the other hand, may start behaving antisocially due to inadequate parental monitoring and supervision during adolescence. Lack of monitoring leads to increased association with deviant peers, which promotes antisocial behavior. Late starters may resist such behavior when they have access to better alternatives.

Similarly, Moffitt’s (1993) life-course persistent versus adolescent-limited model distinguishes between two types of antisocial behavior. Adolescent-limited antisocial behavior is a result of the “maturity gap” between adolescents’ dependence on and control by adults and their desire to demonstrate their freedom from adult constraint. As adolescents continue to develop and gain access to legitimate adult roles and privileges, there are fewer incentives to engage in antisocial behavior, leading to resistance.

Anxiety and Depression

Adolescence is a crucial period in the developmental models of anxiety and depression. Gender differences in prevalence rates also arise during this period and continue into adulthood. Specific anxiety and depression diagnoses vary in rates, but some disorders have higher rates in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood. These mental health issues are particularly concerning due to their association with suicide, which is one of the leading causes of death during adolescence.

Family adversity, like abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood can lead to social and behavioral problems during adolescence. These situations can cause stress in relationships, leading to poor conflict resolution and excessive seeking of reassurance. Adolescents may also select more maladaptive social contexts, like choosing depressed peers as friends and co-ruminating, exacerbating negative affect and stress. Adolescents with goals related to intimacy and social approval are more vulnerable to relationship disruptions. Anxiety and depression can then worsen problems in social relationships, contributing to the stability of anxiety and depression over time.

Anxiety is an unpleasant state of inner turmoil characterized by feelings of dread over anticipated events. Depression is a state of low mood, leading to aversion to activity.

Academic Achievement

Students spend more time in school during adolescence than in any other setting (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). Parental involvement, intrinsic motivation, and school quality influence academic achievement during this period. Doing well academically marks positive adjustment and sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. On the other hand, dropping out of school poses serious consequences, such as unemployment or underemployment in adulthood. High academic achievement, however, can pave the way for college or vocational training and better opportunities in the future.

Social Media and Adolescence

Social media has become an integral part of many teenagers’ lives. Adolescents often start using technology and social media during a critical period of brain development. However, excessive use of social media can lead to psychological and behavioral issues. Social media refers to websites and apps that allow users to share and create content or participate in social networking.

Diversity within Adolescence

Although similar biological changes occur for adolescents as they enter puberty, these changes can differ significantly depending on one’s cultural, ethnic, and societal factors.

Adolescent development does not necessarily follow the same pathway for all individuals. Certain features of adolescence, particularly biological changes associated with puberty and cognitive changes related to brain development, are relatively universal. However, other elements of adolescence depend largely on more environmentally variable circumstances. For example, adolescents growing up in one country might have different opportunities for risk-taking than adolescents in another. Supports and sanctions for other adolescent behaviors depend on laws and values regarding where adolescents live. Likewise, cultural norms regarding family and peer relationships shape adolescents’ experiences in these domains. For example, in some countries, adolescents’ parents are expected to retain control over significant decisions. In contrast, adolescents are expected to begin sharing or taking control of decision-making in other countries.

Even within the same country, adolescents’ gender, ethnicity, immigrant status, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and personality can shape how adolescents behave and how others respond to them, creating diverse developmental contexts for different adolescents. For example, early puberty (that occurs before most other peers have experienced puberty) appears to be associated with worse outcomes for females than males, likely in part because females who enter puberty early tend to associate with older males, which in turn tends to be associated with early sexual behavior and substance use. For adolescents who are ethnic or sexual minorities, discrimination sometimes presents a set of challenges that non-minorities do not face.

Finally, genetic variations contribute an additional source of diversity in adolescence. Current approaches emphasize gene X environment interactions, often following a differential susceptibility model (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). Genetic variations are considered riskier than others, but genetic variations can also make adolescents more or less susceptible to environmental factors. Thus, it is crucial to be mindful that individual differences play an important role in adolescent development.

So, What Have You Learned?

Biological, cognitive, and social changes mark adolescent development. Adolescents begin to spend more time with peers, become more independent from their parents, and start exploring romantic relationships and sexuality. Identity formation is a significant aspect of adolescent development, which involves exploring different identities before committing to one. The adolescent period is characterized by risky behavior, which is influenced by the brain’s development. The reward-processing centers in the brain mature more quickly than cognitive control systems, leading adolescents to be more sensitive to rewards than the potential negative consequences. However, adolescent experiences can vary widely based on factors such as gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and country of residence.

References

This chapter was adapted from select chapters in Iowa State University Digital Press Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being, authored by Diana Lang, Nick Cone, Tera Jones, and Lumen Learning, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908.

Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54.

Bleil, M. E., Booth-LaForce, C., & Benner, A. D. (2017). Race disparities in pubertal timing: Implications for cardiovascular disease risk among African American women. Population research and policy review, 36(5), 717–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-017-9441-5

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley

Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 225–241.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York, NY: Norton.

Freeman, H.; Magee, B.; Ortis, G.; Lebrun, A. (2023, June 26). Growing Up as an Adolescent in Louisiana—Developmental Psychology. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OXXvEVl6Yak

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford.

Hartley, C. A. & Somerville, L. H. (2015). The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 5, 108-115.

Kim, E. (2016, June 20). James Marcia’s Adolescent Identity Development. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/-JrZwmHU9xE

Levine, L. E. & Munsch, J. (2015). Child Development from Infancy to Adolescence. Retrieved from https://edge.sagepub.com/levinechrono on June 5, 2023.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020205

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life course persistent antisocial behavior: Developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Phinney, J. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34–49.

Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372–1384.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085.

Steinberg, L. (2013). Adolescence (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

The University of North Carolina and Chapel (2023). Study Shows Habitual Checking of Social Media May Impact Young Adolescents’ Brain Development. Retrieved from https://www.unc.edu/posts/2023/01/03/study-shows-habitual-checking-of-social-media-may-impact-young-adolescents-brain-development/#:~:text=The%20study%20findings%20suggest%20that,more%20sensitive%20to%20social%20feedback on June 5, 2023.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Attribution

Tremika Cleary adapted this chapter from select chapters in Iowa State University Digital Press Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being, authored by Diana Lang, Nick Cone, Tera Jones; and Lumen Learning, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Girls at a beach © Tremika Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Lobes_of_the_brain_NL.svg © Henry Vandyke Carter (1831–1897) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 7-4 Graduation © Tremika Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license