Chapter 5: Early Childhood

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Summarize overall physical growth during early childhood.

- Describe the growth of structures in the brain during early childhood.

- Identify examples of gross and fine motor skill development in early childhood.

- Identify nutritional concerns for children in early childhood.

- Examine the nutritional content of popular foods consumed by children in early childhood.

- Describe sexual development in early childhood.

- Define preoperational intelligence.

- Illustrate animism, egocentrism, and centration using children’s games or media.

- Describe language development in early childhood.

- Illustrate scaffolding.

- Explain private speech.

- Explain the theory of mind.

- Explain Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development for toddlers and children in early childhood.

- Contrast models of parenting styles.

- Explain theories of self from Cooley and Mead.

- Summarize theories of gender role development.

- Examine concerns about childhood stress and development.

Louisiana Snapshot

While Louisiana often ranks at or near the bottom of educational attainment in U.S. statistics, one significant improvement has been made in supporting and regularizing early childhood education. In 2012, the state legislature passed the Early Childhood Education Act (Act 3), which seeks to improve all publicly funded early childhood education sites through the implementation of common standards, a single enrollment system, and the creation of an advisory council consisting of parents, childcare professionals, and community leaders for the state’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) to guide Act 3 implementation. Subsequent legislation has offered a framework for the organization, reporting, and assessment of these efforts in Louisiana, while subsequent grants have provided significant funding. In the later 2020s, these students will enroll in colleges and universities. At that point, educational statistics will be available to chart the complete path of educational attainment in this first generation of students raised with the benefit of these programs.

Taken from State of Early Care and Education – LPIC. (2021, December 13). Policyinstitutela.org. https://policyinstitutela.org/early-childhood/state-of-early-care-and-education/

The time between a child’s second and sixth birthday is a time of rich development in many ways. Children are proliferating physically, cognitively, and socially. Children are developing language skills to help them navigate their world as they prepare for school. A child will go from being able to produce approximately 50 words at age 2 to making over 2000 words at age 6! The number of words these children understand is even more significant!

Children in this stage change from intuitive problem-solvers into more sophisticated logical problem-solvers. Their cognitive skills are increasing at a rapid rate, even though their brain is beginning to lose neurons through the process of synaptic pruning.

Children are also learning to navigate the social world around them. They are learning about themselves and begin to develop their self-concept, while at the same time, they are becoming aware that other people have feelings, too. The development in these four years impacts the rest of the child’s life in many ways for years to come.

Physical Development

Growth in Early Childhood

Children in early childhood are physically growing at a rapid pace. If you want to have fun with a child at the beginning of the period, ask them to take their left hand and use it to go over their head to touch their right ear. They cannot do it. Their body proportions are such that they are still built like infants with very large heads and short appendages. By the time the child is five years old, though, their arms will have stretched, and their head is becoming smaller in proportion to the rest of their growing bodies. They can accomplish the task easily because of these physical changes.

Children between the ages of 2 and 6 years tend to grow about 3 inches in height each year and gain about 4 to 5 pounds yearly. The average 6-year-old weighs about 46 pounds and is about 46 inches tall. The 3-year-old is similar to a toddler with a large head, large stomach, and short arms and legs. But by the time the child reaches age 6, the torso has lengthened, and body proportions have become more like those of adults.

This growth rate is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite between the ages of 2 and 6. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits.

Nutritional Concerns

Caregivers who have established a feeding routine with their child can find this reduction in appetite a bit frustrating and become concerned that the child will starve. However, by providing adequate, sound nutrition and limiting sugary snacks and drinks, the caregiver can be assured that (1) the child will not starve and (2) the child will receive adequate nutrition. Preschoolers can experience iron deficiencies if not given well-balanced nutrition or too much milk. Calcium interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well.

Caregivers must remember that they are setting up taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to high-fat, sweet, and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods with more subtle flavors, such as fruits and vegetables.

Tips for Establishing Healthy Eating Patterns

Consider the following advice about establishing eating patterns for years to come (Rice, 1997). The main goals are keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition, and not engaging in power struggles over food.

1. Don’t force your child to eat or fight over food. Of course, it is impossible to force someone to eat. But the better advice is to avoid turning food into ammunition during a fight. Do not teach your child to eat or refuse to eat to gain favor or express anger toward someone else.

2. Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help realize that appetites vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat.

3. Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Mealtimes should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress.

4. No short-order chefs. While it is okay to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when hungry, and the meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” continuously can help create an appetite for whatever is being served.

5. Limit choices. If you give your preschool-aged child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking, “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or choose whatever their sibling does not!

6. Serve balanced meals. This tip encourages caregivers to serve balanced meals. A box of macaroni and cheese is not a balanced meal. Meals prepared at home tend to have better nutritional value than fast food or frozen dinners. Prepared foods tend to have higher fat and sugar content as these ingredients enhance taste and profit margin because fresh food is often more costly and less profitable. However, preparing fresh food at home is not expensive. It does, however, require more activity. Preparing meals and including the children in kitchen chores can provide a fun and memorable experience.

7. Don’t bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetables by promising dessert is not a good idea. For one reason, the child will likely find a way to get the dessert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in). It also teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. A child, for example, may learn the broccoli they have enjoyed is seen as yucky by others unless it’s smothered in cheese sauce!

To what extent do these tips address cultural practices? How might these tips vary by culture?

Brain Maturation

The brain is about 75 percent of its adult weight by two years of age. By age 6, it is at 95 percent of its adult weight. The development of myelin (myelination) and new synapses (through synaptic pruning) continues in the cortex. We see a corresponding change in what the child can do as it does. Remember that myelin is the coating around the axon that facilitates neural transmission. Synaptic pruning refers to the loss of unused synapses. As myelination and pruning increase during this stage of development, neural processes become quicker and more complex.

A more significant development in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain behind the forehead that helps us to think, strategize, and control emotions, makes it increasingly possible to control emotional outbursts and to understand how to play games. Consider 4- or 5-year-old children and how they might approach a soccer game. Chances are every move would be a response to the commands of a coach standing nearby calling out, “Run this way! Now, stop. Look at the ball. Kick the ball!” And when the child is not being told what to do, they are likely looking at the clover on the ground or a dog on the other side of the fence! Understanding the game, thinking ahead, and coordinating movement improves with practice and myelination. Demonstrating resilience and recovering from a loss, hopefully, does as well.

Growth in the Hemispheres and Corpus Callosum

Between ages 3 and 6, the brain’s left hemisphere grows dramatically. This side of the brain or hemisphere is typically involved in language skills. The right hemisphere continues to grow throughout early childhood and is engaged in tasks that require spatial skills, such as recognizing shapes and patterns. The corpus callosum, which connects the brain’s two hemispheres, undergoes a growth spurt between ages 3 and 6, resulting in improved coordination between right and left hemisphere tasks.

Visual Pathways

Have you ever examined the drawings of young children? If you look closely, you can almost see the development of visual pathways reflected in how these images change as pathways become more mature. Early scribbles and dots illustrate the use of simple motor skills. No real connection is made between a picture being visualized and what is created on paper.

At age 3, the child begins to draw wispy creatures with heads and not much other detail. Gradually, pictures start to have more detail and incorporate more parts of the body. Arm buds become arms, and faces take on noses, lips, and eyelashes. Look for drawings you or your child created to see this fascinating trend. Here are some pictures my daughters drew from ages 2 to 7 years.

Motor Skill Development

Remember that gross motor skills are voluntary movements involving large muscle groups. In contrast, fine motor skills are more exact movements of the hands and fingers, including the ability to reach and grasp an object. Early childhood is a time of gross and fine motor development.

Early childhood is when children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging, and clapping; every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant allows you to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood. Children continue to improve their gross motor skills as they run and jump. They frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs often accompany arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right.

Fine motor skills are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs also promote fine motor skills (have you ever heard of the song “itsy, bitsy, spider”?). Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s fingernails or tying shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Motor skills continue to develop in middle childhood for preschoolers, and play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

Sexual Development in Early Childhood

Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). A more modern approach to sexuality suggests that the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. That said, it seems to be the case that the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that are part of the adult meanings of sexuality are not present in sexual arousal at this stage. In contrast, sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensations and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Infancy

Boys and girls are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. Infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood

Self-stimulation is expected in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and others’ bodies is also a natural part of early childhood. Consider this example. A mother is asked by her young daughter: “So it’s okay to see a boy’s privates as long as it’s the boy’s mother or a doctor?” The mother hesitates a bit and then responds, “Yes. I think that’s alright.” “Hmmm,” the girl begins, “When I grow up, I want to be a doctor!” Hopefully, this subject is approached in a way that teaches children to be safe and know what is appropriate without frightening them or causing shame.

As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers to take off their clothes and touch each other (Okami et al., 1997). Masturbation is common for both boys and girls. Boys are often shown by other boys how to masturbate. But girls tend to find out accidentally. And boys masturbate more frequently and touch themselves more openly than girls (Schwartz, 1999).

Hopefully, parents respond to this without undue alarm or making the child feel guilty about their bodies. Instead, messages about what is happening and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn what is right.

Cognitive Development

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning some basic principles about how it works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, how many of you fear you will go down the bathtub drain? Hopefully, none of you do! But a child of three might worry about this as they sit at the front of the bathtub. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size, and distance are difficult to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact, and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.

Preoperational Intelligence

Remember that Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain balance in understanding the world. With rapid motor skills and language development increases, young children constantly encounter new experiences, objects, and words. In the module covering main developmental theories, you learned that when faced with something new, a child may either assimilate it into an existing schema by matching it with something they already know or expand their knowledge structure to accommodate the unique situation. Many of the child’s schemas will be challenged, developed, and rearranged during the preoperational stage. Their whole view of the world may shift.

Piaget’s second stage of cognitive development is called the preoperational stage and coincides with ages 2-7 (following the sensorimotor stage). The word operation refers to using logical rules, so sometimes this stage is misinterpreted as implying that children are illogical. While it is true that children at the beginning of the preoperational stage tend to answer questions intuitively as opposed to logically, children in this stage are learning to use language and how to think about the world symbolically. These skills help children develop the foundations they need to use operations consistently in the next stage. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play: Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond how it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything initially intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

Piaget believed that children’s pretend play and experimentation helped them solidify the new schemas they were developing cognitively. This involves both assimilation and accommodation, which results in changes in their conceptions or thoughts. As children progress through the preoperational stage, they form the knowledge they need to use logical operations in the next stage.

Egocentrism: Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a 3-dimensional mountain model and asking them to describe what a doll looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture of themselves rather than the doll’s view. However, when speaking to others, children use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger or older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Syncretism: Syncretism refers to a tendency to think that if two events coincide, one causes the other. I remember my daughter asking if she could wear her bathing suit and whether it would be summer!

Animism: Animism refers to attributing lifelike qualities to objects. The cup is alive, the chair that falls and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys must stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age 3, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Watch It

Watch this segment in which the actor Robin Williams sings a song to teach children the difference between what is alive and what is not. (Interestingly, the puppets in the background sing and dance the phrase “it’s not alive.” This might be a bit confusing to the viewers!)

Classification Errors: Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that objects can be classified differently. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. The ability to classify objects improves as the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed.

Conservation Errors: Conservation refers to recognizing that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Imagine a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old eating lunch. The 4-year-old has a whole peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He notices, however, that his younger sister’s sandwich is cut in half and protests, “She has more!”

Watch It

Theory of Mind

Imagine showing a child of three a Band-Aid box and asking the child what is in the box. Chances are, the child will reply, “Band-Aids.” Now, imagine that you open the box and pour out crayons. If you ask the child what they thought was in the box before it was opened, they may respond, “Crayons.” If you ask what a friend would have thought was in the box, the response would still be “crayons.” Why? Before about four years of age, a child does not recognize that the mind can hold ideas that are not accurate. So, this 3-year-old changes their response once shown that the box contains crayons. The theory of mind is the understanding that the mind can be tricked or is not always accurate. Around age 4, the child would reply, “Crayons,” and understand that thoughts and realities do not always match.

This awareness of the existence of the mind is part of social intelligence or the ability to recognize that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us differently, and it allows us to be understanding or empathic toward others. This mind-reading ability helps us to anticipate and predict the actions of others (even though these predictions are sometimes inaccurate).

The awareness of the mental states of others is essential for communication and social skills. A child who demonstrates this skill can anticipate the needs of others.

Was Piaget correct?

Children in the preoperational stage seem to make the logical mistakes that Piaget suggests they will make. That said, it is essential to remember that there is variability in the ages at which children reach and exit each stage. Further, there is some evidence that children can be taught to think more logically before the end of the preoperational period. For example, as soon as a child can reliably count, they may be able to learn the conservation of numbers. For many children, this is around age five. More complex conservation tasks, however, may not be mastered until closer to the end of the stage, around age seven.

Language Development

Vocabulary Growth

A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of 2 and 6 from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through fast-mapping. Words are quickly learned by connecting new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese and those speaking English tend to learn nouns more readily. However, those teaching less verb-friendly languages, such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai et al., 2008). Children are also very creative in creating their own words to use as labels, such as “take-care-of” when referring to John, the character in the cartoon Garfield, who cares for the cat.

Literal Meanings

Children can repeat words and phrases after hearing them only once or twice. However, they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech taken literally. For example, two preschool-aged girls began to laugh loudly while listening to a recording of Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” when the narrator reports, “Prince Phillip lost his head!” They imagine his head popping off and rolling down the hill as he runs and searches for it. Or a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking, “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization

Children learn the rules of grammar as they learn the language. Some of these rules are not taught explicitly, and others are. Often, when learning language intuitively, children apply rules inappropriately at first. But even after successfully navigating the rule for a while, at times, explicitly teaching a child a grammar rule may cause them to make mistakes they had previously not made. For instance, two- to three-year-old children may say, “I goed there” or “I doed that,” as they understand intuitively that adding “ed” to a word makes it mean “something I did in the past.” As the child hears the correct grammar rule applied by the people around them, they correctly begin to say, “I went there” and “I did that.” It would seem that the child has solidly learned the grammar rule, but it is common for the developing child to revert to their original mistake. This happens as they overregulate the rule. This can happen because they intuitively discover the rule and overgeneralize it or are explicitly taught to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense in school. A child who had previously produced correct sentences may start to form incorrect sentences, such as, “I goed there. I doed that.” These children can quickly re-learn the proper exceptions to the -ed rule.

Vygotsky and Language Development

Vygotsky differed from Piaget in that he believed that a person has a set of abilities and potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. He believed that through guided participation, known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a specific range, known as the zone of proximal development. While Piaget’s ideas of cognitive development assume that development through certain stages is biologically determined, originates in the individual, and precedes cognitive complexity, Vygotsky presents a different view in which learning drives development. Rather than being determined by the learner’s developmental level, the idea of learning driving development fundamentally changes our understanding of the learning process and has significant instructional and educational implications (Miller, 2011).

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them, described what you did while you demonstrated the skill, and let them work with you throughout the process. You assisted them when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do, you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding. Educators have also adopted this approach to teaching. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they can do with the proper guidance.

This difference in assumptions has significant implications for designing and developing learning experiences. Suppose we believe, as Piaget did, that development precedes learning. In that case, we will ensure that new concepts and problems are not introduced until learners have developed innate capabilities to understand them. On the other hand, if we believe, as Vygotsky did, that learning drives development and that development occurs as we learn a variety of concepts and principles, recognizing their applicability to new tasks and situations, then our instructional design will look very different.

Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations, and encourage elaboration. For example, if the child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” the adult responds, “You went there?” As Noam Chomsky suggested in his theory of universal grammar, children may be hard-wired for language development, but active participation is also essential. The scaffolding process is where the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned. Repeating what a child has said, but in a grammatically correct way, is scaffolding for a child struggling with the rules of language production.

Private Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feeling very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves, too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from others’ points of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private or inner speech. Thinking out loud finally becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only when trying to learn something or remember something, etc. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).

Psychosocial Development

A Look at Self-Concept, Gender Identity, and Family Life

The time between a child’s second and sixth birthday is full of new social experiences. At the beginning of this stage, a child selfishly engages in the world—the goal is to please the self. As the child ages, they realize that relationships are built on give-and-take. They start to learn to empathize with others. They know how to make friends. Learning to navigate the social sphere is difficult, but children do it readily.

While the child is learning about their place in various relationships, they are also developing an understanding of emotion. A two-year-old does not have a good grasp on their emotions, but by the time a child is six, they understand their emotions better. They also understand how to control their emotions—even to the point that they may put on a different emotion than they are feeling. Further, when children are six, they understand that other people have emotions and that all emotions involved (theirs and other people’s) should be considered. That said, although the six-year-olds understand these things, they are not always good at putting the knowledge into action. We’ll examine some of these issues in this section.

Self-Concept

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. A self-concept or idea of who we are, what we are capable of doing, and how we think and feel is a social process that involves considering how others view us. It might be said that you must interact with others to develop a sense of self. Interactionist theorists Cooley and Mead offer two interesting explanations of how a sense of self develops.

Interactionism and Views of Self

Cooley’s Looking-Glass Self

Charles Horton Cooley (1964) suggests that our self-concept comes from looking at how others respond to us. This process, known as the looking-glass self, involves looking at how others seem to view us and interpreting this as we judge whether we are good or bad, strong or weak, beautiful or ugly, and so on. Of course, we do not always interpret their responses accurately, so our self-concept is not simply a mirror reflection of the views of others. After forming an initial self-concept, we may use it as a mental filter, screening out those responses that do not seem to fit our ideas of who we are. So, compliments may be negated, for example.

Think of times in your life when you feel self-conscious. The process of the looking-glass self is pronounced when we are preschoolers or perhaps when we are in a new school or job or are taking on a new role in our personal lives and trying to gauge our performances. When we feel sure of who we are, we focus less on how we appear to others.

Mead’s I and Me

Herbert Mead (1967) explains how we develop a social sense of self by being able to see ourselves through the eyes of others. There are two parts of the self: the “I,” which is the part of the self that is spontaneous, creative, innate, and not concerned with how others view us, and the “me,” or the social definition of who we are.

When we are born, we are all “I” and act without concern about how others view us. But the socialized self begins when we consider how one important person views us. This initial stage is “taking the role of the significant other.” For example, a child may pull a cat’s tail and be told by his mother, “No! Don’t do that, that’s bad,” while receiving a slight slap on the hand. Later, the child may mimic the same behavior toward the self and say aloud, “No, that’s bad,” while patting his hand. What has happened? The child can see himself through the eyes of the mother. As the child grows and is exposed to many situations and rules of culture, he begins to view the self in the eyes of many others through these cultural norms or rules. This is referred to as “taking the role of the generalized other,” resulting in a sense of self with many dimensions. The child understands self as a student, friend, son, etc.

Exaggerated Sense of Self

One of the ways to gain a clearer sense of self is to exaggerate those qualities to be incorporated into the self. Preschoolers often exaggerate their qualities or seek validation as the biggest or brightest child who can jump the highest. Much of this may be due to the simple fact that the child does not understand their limits. Young children may believe they can beat their parents to the mailbox or pick up the refrigerator.

This exaggeration tends to be replaced by a more realistic sense of self in middle childhood as children realize they have limitations. Part of this process includes having parents who allow children to explore their capabilities and give the child authentic feedback. Another essential aspect of this process involves the child learning that other people have abilities, too…and that the child’s capabilities may differ from those of others. Children learn to compare themselves to others to understand what they are “good at” and not as good at.

Erikson: Initiative vs. Guilt

The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take the initiative or to think of ideas and initiate action. Children are curious at this age and start to ask questions to learn about the world. Parents should try to answer those questions without making the child feel like a burden or implying that the child’s question is not worth asking.

Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they can initiate activities and assert control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative vs. guilt. Preschool children can master this task by learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others. Initiative, a sense of ambition and responsibility, occurs when parents allow a child to explore within limits and then support the child’s choice. These children will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage—with their initiative misfiring or stifled by over-controlling parents—may develop guilt.

These children are also beginning to use their imagination (remember what we learned when we discussed Piaget). Children may want to build a fort with cushions from the living room couch, open a lemonade stand in the driveway, or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Another way that children may express autonomy is by wanting to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being overly critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pale in comparison to the smiling face of a five-year-old emerging from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas!

The parent must do their best to guide the child to the right actions. Remember that according to Freud and Kohlberg, children develop a sense of morality during this time. Erikson agrees. If the child does leave those soggy washrags in the sink, have the child help clean them up. It is possible that the child will not be happy with helping clean and may even become aggressive or angry, but it is essential to remember that the child is still learning how to navigate their world. They are trying to build a sense of autonomy and may not react well when asked to do something they had not planned. Parents should be aware of this and try to be understanding and firm. Guilt for a situation where a child did not do their best allows them to understand their responsibilities and helps them learn to exercise self-control (remember the marshmallow test). The goal is to find a balance between initiative and guilt, not a free-for-all where the parent allows the child to do anything they want to. The parent must guide the child to resolve this stage successfully.

Gender Identity, Gender Constancy, and Gender Roles

Another critical dimension of the self is the sense of self as male or female. Preschool-aged children become increasingly interested in discovering the physical differences between boys and girls and acceptable activities. While two-year-olds can identify differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. This self-identification, or gender identity, is followed sometime later with gender constancy, or the understanding that superficial changes do not mean gender has changed. For example, if you play with a two-year-old boy and put barrettes in his hair, he may protest, saying he doesn’t want to be a girl. When a child is four years old, they understand that putting barrettes in their hair does not change their gender.

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Children may also use gender stereotyping readily. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. A recent research study examined four- and five-year-old children’s predictions concerning the sex of the persons carrying out various everyday activities and occupations on television. The children’s responses revealed gender-stereotyped solid expectations. They also found that children’s estimates of their future competence indicated stereotypical beliefs, with the females more likely to reject masculine activities.

Children who are allowed to explore different toys, who are exposed to non-traditional gender roles, and whose parents and caregivers are open to allowing the child to take part in non-traditional play (allowing a boy to nurture a doll or allowing a girl to play doctor) tend to have broader definitions of what is gender appropriate and may do less gender stereotyping.

Freud and the Phallic Stage

The phallic stage occurs during preschool (ages 3-5) when the child faces a new biological challenge. The child will experience the Oedipus complex, which refers to a child’s unconscious sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent and hatred for the same-sex parent. For example, boys experiencing the Oedipus complex will unconsciously want to replace their father as a companion to their mother but then realize that the father is much more powerful. For a while, the boy fears that if he pursues his mother, his father may castrate him (castration anxiety). So rather than risk losing his penis, he gives up his affection for his mother and instead learns to become more like his father, imitating his actions and mannerisms, thereby retaining the role of males in his society. From this experience, the boy learns a sense of masculinity. He also knows what society thinks he should do and experiences guilt if he does not comply. In this way, the superego develops. If he does not resolve this successfully, he may become a “phallic male” or a man who constantly tries to prove his masculinity (about which he is insecure) by seducing women and beating up men.

Girls experience a comparable conflict in the phallic stage—the Electra complex. While often attributed to Freud, the Electra complex was proposed by Freud’s contemporary Carl Jung (Jung & Kerenyi, 1963). A little girl experiences the Electra complex in which she is attracted to her father but realizes that she cannot compete with her mother, so she gives up that affection and learns to become more like her mother. This is not without some regret, however. Freud believed that the girl feels inferior because she does not have a penis (experiences “penis envy”). But she must resign herself to the fact that she is female and will have to learn her inferior role in society as a female. However, if she does not resolve this conflict successfully, she may have a weak sense of femininity and grow up to be a “castrating female” who tries to compete with men in the workplace or other areas of life. The superego formation occurs during the dissolution of the Oedipus and Electra complex.

Chodorow and Mothering

Chodorow, a neo-Freudian, believed that mothering promotes gender stereotypic behavior. Mothers push their sons away too soon, directing their attention toward problem-solving and independence. As a result, sons grow up confident in their abilities but uncomfortable with intimacy. Girls are kept dependent for too long and are given unnecessary and even unwelcome assistance from their mothers. Girls learn to underestimate their abilities and lack assertiveness but feel comfortable with intimacy.

Both models assume that early childhood experiences result in lifelong gender self-concepts. However, gender socialization is a process that continues throughout life. Children, teens, and adults refine and can modify their sense of self based on gender.

Learning through Reinforcement and Modeling

Learning theorists suggest that gender role socialization results from how parents, teachers, friends, schools, religious institutions, media, and others send messages about acceptable or desirable behavior for males or females. This socialization begins early—it may even start when a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and potential on the part of a parent. And this stereotyping continues to guide perception through life. Consider parents of newborns. A 7-pound, 20-inch baby wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describes the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents will likely describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Female infants are held more, talked to more frequently, and given direct eye contact, while male infants’ play is often mediated through a toy or activity.

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, superhero paraphernalia, and active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Daughters are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender normative behavior (Caldera, Huston, & O’Brien 1998).

Sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and have to be performed only on occasion, while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home, such as cleaning or cooking, which are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when encountering problems, and daughters are more likely to be assisted even when working on an answer. This impatience is reflected in teachers waiting less time when asking a female student for a response than when asking for a reply from a male student (Sadker and Sadker, 1994). Teachers teach girls to try harder and endure to succeed, while boys’ successes are attributed to their intelligence. Of course, the stereotypes of advisors can also influence which kinds of courses or vocational choices girls and boys are encouraged to make.

Friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls, and popularity may be based on modeling the ideal behavior or appearance for the sexes. Girls tend to tell one another secrets to validate others as best friends, while boys compete for positions by emphasizing their knowledge, strength, or accomplishments. This focus on accomplishments can even give rise to exaggerating accomplishments in boys, but girls are discouraged from showing off and may learn to minimize their accomplishments.

Gender messages abound in our environment. But does this mean that each of us receives and interprets these messages similarly? Probably not. In addition to being recipients of these cultural expectations, we are individuals who also modify these roles (Kimmel, 2008).

One interesting recent finding is that girls may have an easier time breaking gender norms than boys. Girls who play with masculine toys often do not face the same ridicule from adults or peers that boys face when they want to play with feminine toys. Girls also face less ridicule when playing a masculine role (like doctor) as opposed to a boy who wants to take a feminine role (like caregiver).

The Impact of Gender Discrimination

How much does gender matter? In the United States, gender differences are found in school experiences. Even in college and professional school, girls are less vocal in class and much more at risk for sexual harassment from teachers, coaches, classmates, and professors. These gender differences are also found in social interactions and media messages. The stereotypes that boys should be firm, forceful, active, dominant, and rational and that girls should be pretty, subordinate, unintelligent, emotional, and talkative are portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music. In adulthood, these differences are reflected in income gaps between men and women (women working full-time earn about 74 percent of the income of men), higher rates of women suffering rape and domestic violence, higher rates of eating disorders for females, and higher rates of violent death for men in young adulthood.

Gender differences in India can be a matter of life and death as preferences for male children have been historically strong and are still held, especially in rural areas (WHO, 2010). Male children prefer receiving food, breast milk, medical care, and other resources. In some countries, it is no longer legal to give parents information on the sex of their developing child for fear that they will abort a female fetus. Gender socialization and discrimination still impact development in a variety of ways across the globe. Gender discrimination generally persists throughout the lifespan in the form of obstacles to education or lack of access to political, financial, and social power.

Family Life

Parenting Styles

Relationships between parents and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood. We will explore two models of parenting styles. Keep in mind that most parents do not follow any model completely. Real people tend to fall somewhere in between these styles. Sometimes, parenting styles change from one child to the next or when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting. Parenting styles can also be affected by parent concerns in other areas of their life. For example, parenting styles tend to become more authoritarian when parents are tired and perhaps more authoritative when they are more energetic. Sometimes, parents seem to change their parenting approach when others are around, maybe because they become more self-conscious as parents or are concerned with giving others the impression that they are a “tough” parent or an “easy-going” parent. And, of course, parenting styles may reflect the type of parenting someone saw modeled while growing up.

Baumrind

Baumrind (1971) offers a model of parenting that includes three styles:

Authoritarian Parenting

The first, authoritarian, is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggests that strict parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer perhaps as bullies toward peers.

Permissive Parenting

Permissive parenting involves holding expectations of children below what could be reasonably expected from them. Children are allowed to make their own rules and determine their activities. Parents are warm and communicative but provide little structure for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits.

Authoritative Parenting

Authoritative parenting involves being appropriately strict, reasonable, and affectionate. Parents allow negotiation where appropriate, and discipline matches the severity of the offense. A popular parenting program offered in many school districts is called “Love and Logic” and reflects the authoritative or democratic style of parenting just described. Uninvolved parents are disengaged from their children. They do not make demands on their children and are non-responsive. These children can suffer in school and in their relationships with peers (Gecas & Self, 1991).

LeMasters and Defrain

LeMasters and Defrain (1989) offer another model of parenting. This model is attractive because it looks more closely at the parent’s motivations and suggests that parenting styles are often designed to meet the parent’s psychological needs rather than the child’s developmental needs.

Martyr

The martyr is a parent who will do anything for the child, even tasks the child should do for themselves. All of the good deeds performed for the child, in the name of being a “good parent,” may be used later should the parent want to gain compliance from the child. If a child goes against the parent’s wishes, the parent can remind the child of all of the times the parent helped the child and evoke a feeling of guilt so that the child will do what the parent wants. The child learns to be dependent and manipulative as a result. (Beware! A parent busy whipping up cookies may be thinking, “control!”)

Pal

The pal is like the permissive parent described in Baumrind’s model above. The pal wants to be the child’s friend. Perhaps the parent is lonely, or maybe the parent is trying to win a popularity contest against an ex-spouse. Pals let children do what they want, focus most on being entertaining and fun, and set few limitations. Consequently, the child may have little self-discipline and try to test limits with others.

Police Officer / Drill Sergeant

The police officer/drill sergeant parenting style is similar to the authoritarian parent described above. The parent focuses primarily on making sure that the child is obedient and that the parent has complete control of the child. Sometimes, this can be taken to extreme by giving the child tasks designed to check their level of obedience. For example, the parent may require that the child fold the clothes and place items back in the drawer in a particular way. If not, the child might be scolded for not doing things “right.” This type of parent has a tough time allowing the child to grow and learn to make decisions independently. The child may have a lot of resentment toward the parent who is displaced by others.

Teacher-Counselor

The teacher-counselor parent pays a lot of attention to expert advice on parenting and believes that as long as all of the steps are followed, the parent can rear a perfect child. “What’s wrong with that?” you might ask. There are two significant problems with this approach. First, at least indirectly, the parent is responsible for the child’s behavior. If the child has difficulty, the parent feels responsible and thinks the solution lies in reading more advice and trying more diligently to follow that advice. Parents can undoubtedly influence children, but considering that the parent is fully responsible for the child’s outcome is faulty. A parent can only do so much and can never have complete control over the child. Another problem with this approach is that the child may get an unrealistic sense of the world and what can be expected from others. For example, if a teacher-counselor parent decides to help the child build self-esteem and has read that telling the child how special they are or how important it is to compliment the child on a job well done, the parent may convey the message that everything the child does is exceptional or extraordinary. A child may come to expect that all of his efforts warrant praise, and in the real world, this is not something one can expect. Perhaps children get more pride from assessing their performance than from having others praise their efforts.

Athletic Coach

So, what is left? LeMasters and Defrain (1989) suggest that the athletic coach parenting style is best. Before you conclude here, set aside any negative experiences you may have had with coaches. The principles of coaching are what are essential to LeMasters and Defrain. A coach helps players form strategies, supports their efforts, gives feedback on what went right and wrong, and stands at the sideline while the players perform. Coaches and referees ensure that the game’s rules are followed and that all players adhere to those rules.

Similarly, the athletic coach, as a parent, helps the child understand what needs to happen in certain situations, whether in friendships, school, or home life, and encourages and advises the child about how to manage these situations. The parent does not intervene or do things for the child. Instead, the parent’s role is to guide while the child learns to handle these situations first-hand. And the rules for behavior are consistent and objective and presented in that way. So, a child who is late for dinner might hear the parent respond this way, “Dinner was at six o’clock.” Rather than, “You know good and well that we always eat at six. If you expect me to get up and make something for you now, you have another thing coming! Who do you think you are showing up late and looking for food? You’re grounded until further notice!”

The most important thing to remember about parenting is that you can be a better, more objective parent when you are directing your actions toward the child’s needs while considering what they can reasonably be expected to do at their stage of development. Parenting is more difficult when you are tired and have psychological needs that interfere with the relationship. Some of the best advice for parents is to avoid taking the child’s actions personally and be as objective as possible.

The impact of class and culture cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The two models of parenting described above assume that authoritative and athletic coaching styles are best because they are designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant, and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures such as the United States, particularly by the middle class. African-American, Hispanic, and Asian parents tend to be more authoritarian than non-Hispanic whites. However, obedience and compliance are favored in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea. Authoritative parenting has been used historically and reflects the cultural need for children to do as they are told. In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, as in the case of raising crops, rearing independent children who strive to be on their own makes no sense. But raising a child to be independent is very important in an economy based on being mobile to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education.

Working-class parents are likelier than middle-class parents to focus on obedience and honesty when raising their children. In a classic study on social class and parenting styles called Class and Conformity, Kohn (1977) explains that parents tend to emphasize qualities needed for their own survival when parenting their children. Working-class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; instead, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children. Middle-class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking the initiative, being self-directed, and being assertive in their jobs. They must get the job done without being told precisely what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture.

Child Care Concerns

About 77.3 percent of mothers of school-aged and 64.2 percent of mothers of preschool-aged children in the United States work outside the home (Cohen and Bianchi, 1999; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). Since more women have been entering the workplace, there has been a concern that families do not spend as much time with their children. This, however, is not true. Between 1981 and 1997, parents’ time with children increased overall (Sandberg and Hofferth, 2001).

Seventy-five percent of children under age 5 are in scheduled childcare programs. Others are cared for by family members or friends or are in Head Start Programs. Older children are often in after-school programs or before-school programs or stay at home alone after school once they are older. Quality childcare programs can enhance a child’s social skills and provide rich learning experiences. But long hours in poor-quality care can have negative consequences for young children. What determines the quality of child care? One consideration is the teacher/child ratio. States specify the maximum number of children that one teacher can supervise. Generally, the younger the children, the more teachers are required for a given number of children. The higher the teacher-to-child ratio, the more time the teacher has for involvement with the children and the less stressed the teacher may be so that the interactions can be more relaxed, stimulating, and positive. The more children there are in a program, the less desirable the program as well. This is because the center may be more rigid in rules and structure to accommodate the large number of children in the facility.

The physical environment should be colorful, stimulating, clean, and safe. The philosophy of the organization and the curriculum available should be child-centered, positive, and stimulating. Providers should be trained in early childhood education as well. A majority of states do not require training for their childcare providers. While formal education is not necessary for a person to provide a warm, loving relationship to a child, knowledge of a child’s development helps address their social, emotional, and cognitive needs effectively. By working toward improving the quality of childcare and increasing family-friendly workplace policies such as more flexible scheduling and perhaps childcare facilities at places of employment, we can accommodate families with smaller children and relieve parents of the stress sometimes associated with managing work and family life.

Cultural Influences on Parenting Styles

The impact of class and culture cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The two models of parenting described above assume that authoritative and athletic coaching styles are best because they are designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant, and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures such as the United States, particularly by the middle class. African-American, Hispanic, and Asian parents tend to be more authoritarian than non-Hispanic whites. However, obedience and compliance are favored in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea. Authoritative parenting has been used historically and reflects the cultural need for children to do as they are told. In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, like raising crops, rearing independent children who strive to be on their own makes no sense. But raising a child to be independent is very important in an economy based on being mobile to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education.

Working-class parents are likelier than middle-class parents to focus on obedience and honesty when raising their children. In a classic study on social class and parenting styles called Class and Conformity, Kohn (1977) explains that parents emphasize qualities needed for survival when parenting their children. Working-class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; instead, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children. Middle-class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking initiative, being self-directed, and being assertive in their jobs. They must get the job done without being told precisely what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture.

Childhood Stress and Development

Stress in Early Childhood

What is the impact of stress on child development? The answer to that question is complex and depends on several factors, including the number of stressors, the duration, and the child’s ability to cope.

Children experience different types of stressors that could be manifested in various ways. Everyday stress can allow young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Even long-lasting stressful events, such as changing schools or losing a loved one, can be managed reasonably well.

Some experts have theorized that there is a point where prolonged or excessive stress becomes harmful and can lead to serious health effects. When stress builds up in early childhood, neurobiological factors are affected; in turn, levels of the stress hormone cortisol exceed normal ranges. Due in part to the biological consequences of excessive cortisol, children can develop physical, emotional, and social symptoms. Physical conditions include cardiovascular problems, skin conditions, susceptibility to viruses, headaches, or stomach aches in young children. Emotionally, children may become anxious or depressed, violent, or feel overwhelmed. Socially, they may become withdrawn, act out towards others, or develop new behavioral ticks such as biting nails or picking at skin.

Conclusion

Usually, sometime at the beginning of early childhood, a parent will suddenly realize that their child is no longer a baby. This may happen because the child has grown physically and no longer has baby-like features, but more often, it is because, suddenly, the parent realizes that this child is becoming independent. The child might be choosing their outfit for the day or trying to learn to tie their shoelaces. It usually happens when the child is around two years old when early childhood begins. This realization that a baby is no longer a baby, that they are a child, is just the beginning.

As you have learned in this module, early childhood is a time of significant change for children. While the child is still obviously a child physically, in the four years of early childhood, they make great strides in development—by the end of this period, a child’s brain is nearly adult-sized! At the same time, that almost adult-sized brain is not ready to perform many adult tasks—there is much learning still to be done in building relationships, moral decision-making, and other cognitive realms. Children go from knowing around 200 words at age two to being able to communicate in adult-like ways with a vocabulary recognizing over 10,000 words by age five, but think about how many new words you have had to learn to succeed in this class! Ten thousand words may sound like a lot, but there are over 170,000 words in English, and the average adult knows over 40,000 words.

Parents caring for children in early childhood contribute significantly to development in direct and indirect ways. Teaching new words, laying down expectations for behavior in different contexts, choosing daycare centers, helping to build self-confidence, and providing general care for the child all contribute to the child’s healthy development through early childhood. Parents and other caretakers should encourage healthy habits in their young children, including healthy food choices and exercising the body and the brain. They should challenge children to think in new ways, create opportunities to learn about themselves, and develop a healthy and realistic self-concept.

The learning that happens for children in early childhood is the stepping stone for the next stage, middle childhood. Many of the advances that began in early childhood will continue to be refined in the next stage.

References

Ariès, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood; a social history of family life. New York: Knopf.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1), part 2.

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the lifespan(4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Cohen, P. N., & Bianchi, S. M. (1999). Marriage, children, and women’s employment: What do we know? Monthly Labor Review, 22-31.

Cooley, C. H. (1964). Human nature and the social order. New York: Schocken Books.

Employment Characteristics of Families Summary. (2010). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved May 05, 2011, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.nr0.htm

Gecas, V., & Self, M. (1991). Families and adolescents. In A. Booth (Ed.), Contemporary families: Looking forward, looking back (National Council on Family Relations). Minneapolis.

Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in unknown noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

Kimmel, M. S. (2008). The gendered society (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kohn, M. L. (1977). Class and conformity. (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

LeMasters, E. E., & DeFrain, J. D. (1989). Parents in contemporary America: a sympathetic view. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Maccoby, E., & Jacklin, C. (1987). Gender segregation in childhood. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 20, 239-287.

Martinson, F. M. (1981). Eroticism in infancy and childhood. In L. L. Constantine & F. M. Martinson (Eds.), Children and sex: New findings, new perspectives. (pp. 23-35). Boston: Little, Brown.

Mead, G. H., & Morris, C. W. (1967). From the standpoint of a social behaviorist, mind, self, and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Middlebrooks, J. S., & Audage, N. C. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. (United States Center for Disease Control, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control). Atlanta, GA.

Nance-Nash, S. (2009, March 5). President’s Fund Repays Liberia’s Market Women | Women’s eNews. Women’s ENews. Retrieved May 05, 2011, from http://womensenews.org/story/business/090305/presidents-fund-repays-liberias-market-women

Okami, P., Olmstead, R., & Abramson, P. R. (1997). Sexual experiences in early childhood: 18-year longitudinal data from UCLA Family Lifestyles Project. Journal of Sex Research, 34(4), 339-347.

Rice, F. P. (1997). Human development: A lifespan approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sadker, M., & Sadker, D. M. (1994). Failing at fairness: How America’s schools cheat girls. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981–1997. Demography, 38, 423-436.

Schwartz, I. M. (1999). Sexual activity before coitus initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(1), 63-69.

State of Early Care and Education – LPIC. (2021, December 13). Policyinstitutela.org. https://policyinstitutela.org/early-childhood/state-of-early-care-and-education/

Vygotskiĭ, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

WHO | Gender and genetics: Sex selection and the law. (2010). Retrieved May 05, 2011, from http://www.who.int/genomics/gender/en/index4.html

Adaptation Statement

Sections of introductory text called in the original Why learn about development during early childhood?, Brain Maturation, Sexual Development, Preoperational Intelligence, Was Piaget correct, Overregularization, Vygotsky and Language Development, Psychosocial Development: A Look at Self-Concept, Gender Identity, and Family Life, Exaggerated Sense of Self, Erikson: Initiative vs. Guilt, Gender Identity, Gender Constancy and Gender Roles, Childhood Stress and Development, and the text the makes up the Conclusion are re-use, with slight adaptation, of content from Early Childhood in Lifespan Development Copyright © 2020 by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. All remaining content is an adaptation of Developmental Psychology Copyright © by Lumen Learning. Bill Pelz Herkimer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted, lightly edited for clarity and to resolve errors, updated throughout with new images, and with the sections: Child Care Concerns and Global Concerns: The Market Women of Liberia removed.

Media Attributions

- nappy-8X5PS8tAqsA-unsplash © https://unsplash.com/@nappystudio is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 20140425_Kipp New Orleans class © Johannah White adapted by Johannah White is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Brothers’ Hands © Shawn Anderson is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- stephen-andrews-tegxWQgZudE-unsplash © Stephen Andrews is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Aidilfitri 2014 © Mohd Fazlin Mohd Effendy Ooi is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

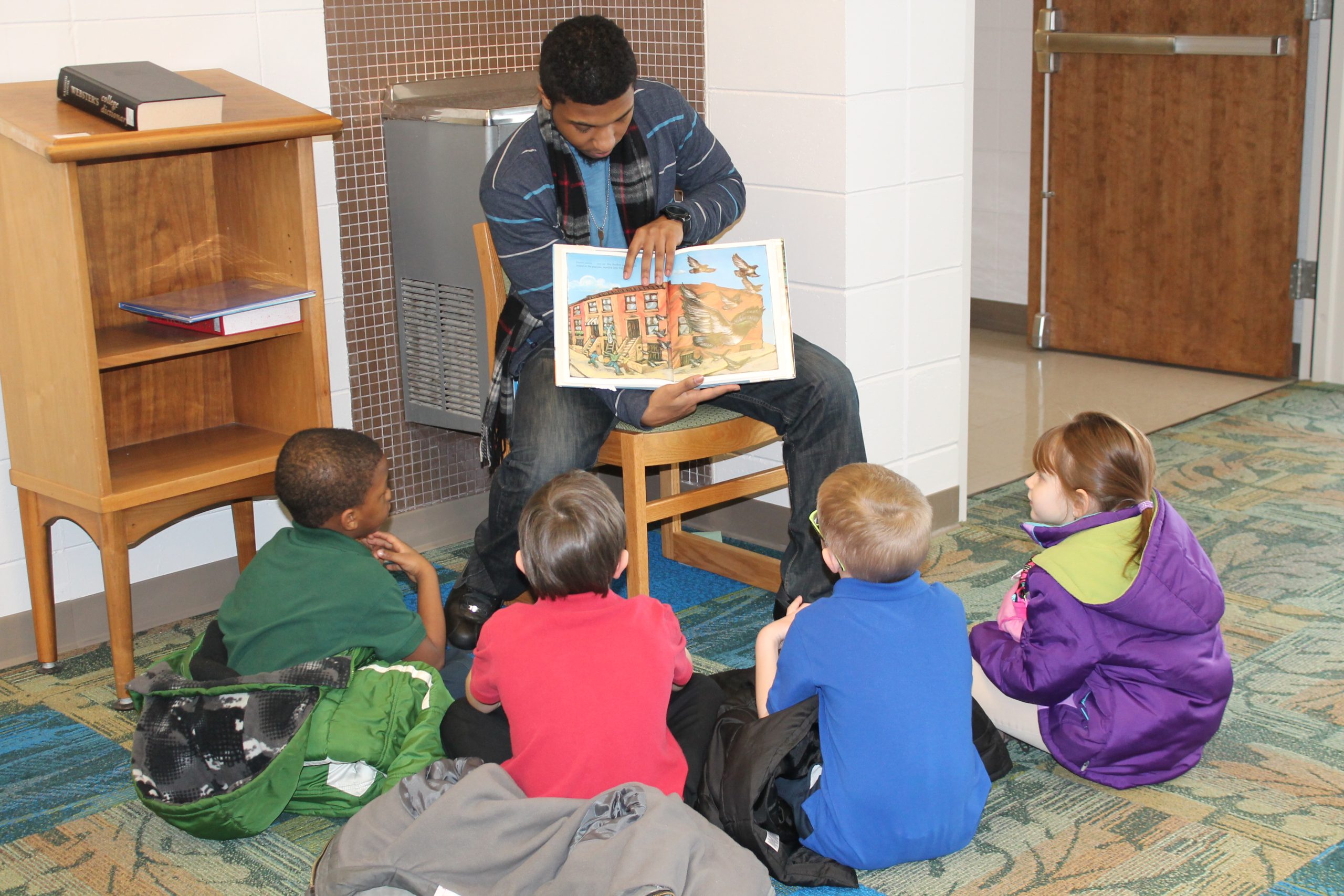

- African American Read-In 2013 © Rod Library is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Ilha Design 2015 © Andreiandrade is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Death By Bubble Gun – A Dyptich © Bernard Tey is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Kleines Mädchen in Bangkok © Stephanie Kraus is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- parents © Caitlin Childs is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primera Dama encabeza bautizo ocho niños de dos partos múltiples © Gobierno Danilo Medina is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

Preoperational stage – the developmental stage when children are learning to think symbolically about the world.

Scaffolding is when a guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

The zone of proximal development (ZPD) is a concept in educational psychology. It represents the space between what a learner can do unsupported and cannot do even with support. It is the range where the learner can perform, but only with support from a teacher or a peer with more knowledge or expertise (a “more knowledgeable other”). The concept was introduced, but not fully developed, by psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) during the last three years of his life. Source: Wikipedia.

Phallic stage - occurs during the preschool years (ages 3-5) when the child has a new biological challenge.

Authoritarian is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient.

A martyr is a parent who will do anything for the child, even tasks the child should do for himself or herself.

Pal is like the permissive parent described in Baumrind’s model who wants to be the child’s friend.

The police officer/drill sergeant parenting style is similar to the authoritarian parent, focusing primarily on ensuring that the child is obedient and that the parent has complete control of the child.

The teacher-counselor parent pays a lot of attention to expert advice on parenting and believes that as long as all of the steps are followed, the parent can rear a perfect child.

Athletic coach style of parenting - the athletic coach as a parent helps the child understand what needs to happen in certain situations, whether in friendships, school, or home life and encourages and advises the child about how to manage these situations. The parent does not intervene or do things for the child.