Chapter 9: Middle Adulthood

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the characteristics of middle adulthood physical and cognitive development.

- Describe the characteristics associated with middle adulthood psychosocial development.

- Recognize how culture plays a role in middle adulthood development.

- Interpret the theoretical development stages that take place during middle adulthood.

- Discuss the common factors associated with academic or career achievement for middle adulthood and the potential barriers they face to success.

Defining Middle Adulthood

Middle adulthood, or midlife, is the period between early and late adulthood. The general age range for this stage is from 40-45 to 60-65, but this can vary based on cultural definitions and expectations. Although research on this developmental period is relatively new, it is an essential stage of life that reflects both developmental gains and losses, and it is currently being studied in more detail. As the large Baby Boom cohort (those born between 1946 and 1964) is now in this stage of life, there has been an increased interest in understanding this critical developmental stage.

While getting out of shape is often associated with aging, it is not inevitable. Physical inactivity, stress, smoking, drinking, poor diet, and chronic diseases such as diabetes and arthritis can all contribute to a decline in overall health. However, adopting healthier lifestyles can help combat many of these changes.

Specific physiological changes are likely to occur in middle adulthood, but regular physical activity can help combat them. Exercise doesn’t have to be intense; even brisk walking thirty minutes daily can make a significant difference. “Use it or lose it” is a good mantra for this stage of development, as the body begins to lose muscle mass and function as we age (known as sarcopenia). From the age of 30, the body loses between 3-8% of muscle mass each decade, and this rate accelerates after the age of 60. However, diet and exercise can help reduce the extent of these changes and their consequences. This section will explore some changes during middle adulthood and discuss how they can impact our daily lives.

What Types of Physical Development Are Experienced during Middle Adulthood?

The importance of avoiding a sedentary lifestyle was apparent to Hippocrates in 400 BCE and remains relevant today. Piasecki et al. (2018) suggest that sarcopenia, the loss of muscle tissue and function as we age, may be caused by leg muscles becoming disconnected from the nervous system. Exercise can encourage new nerve growth, slowing the progression of sarcopenia. By age 75, individuals may have up to 30-60% fewer nerve endings in their leg muscles than in their early 20s.

Although it has only been recognized as an independent disease entity since 2016 (ICD-10), sarcopenia was already assigned its medical code by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2018. Mobility-related diseases will become increasingly costly and affect the quality of life for many people as the population ages. While some doctors and researchers have hesitated to pathologize natural aging changes, mobility is becoming a central concern. Researchers have even identified new conditions such as osteosarcopenia, which describes the decline of muscle tissue and bone tissue (osteoporosis). As the costs of caring for those with mobility issues become apparent, diagnoses and pharmaceuticals that deal with the central question of mobility will become ever more critical.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the third most common form of arthritis, can be developed between the ages of 30 and 60. Its specific cause is unknown, but it occurs when antibodies attack normal synovial fluid in the joints, mistaking them for an alien threat. Women are affected by RA more than men, with a ratio of about 3 to 1. Women are also more likely to experience symptoms at an earlier age. The peak onset of RA for women is estimated to be in their early 40s. Hormonal changes are believed to be the cause of RA because women who are pregnant and have RA often experience temporary remission. While this condition is often associated with those in their 60s, only about a third of people with RA first experience symptoms at this age. However, the symptoms become more acute over time.

Symptoms of Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Symmetrical pattern of affected joints

- Joint inflammation often affects the wrist and finger joints closest to the hand

- Joint inflammation sometimes affects other joints, including the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles, and feet

- Fatigue, occasional fevers, a loss of energy

- Pain and stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes in the morning or after a long rest

- Symptoms that last for many years

- Variability of symptoms among people with the disease.

As people age, they often experience chronic inflammation that does not have a clear cause. This type of inflammation differs from the acute inflammation that occurs with infections. Inflammation is the body’s natural response to injury or harmful pathogens. However, suppose it persists for more extended periods. In that case, it can have serious health effects such as fatigue, fever, chest or abdominal pain, rashes, and increased susceptibility to diseases such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and heart disease. Contributing factors to chronic inflammation include untreated acute inflammation, autoimmune disorders, long-term irritant exposure, and social isolation. Chronic inflammation has also been linked to muscle loss and chronic diseases like dementia. With the aging population, issues related to autoimmune disease, chronic inflammation, and bone mass density will become significant health and social policy concerns in the coming years.

Vision, Hearing, and Other Physical Changes

As people age, they experience some changes in their physical condition that are primarily biological. These changes include problems with vision and hearing, joint pain, and weight gain (Lachman, 2004). Aging affects sight, as the eye’s lens gets larger but loses some flexibility to adjust to visual stimuli. This is called presbyopia, often making it difficult for middle-aged adults to see things up close. Night vision is also affected, as the pupil loses its ability to open and close to accommodate changes in light.

Presbycusis is the primary cause of hearing loss, with one in four people between ages 65 and 74 and one in two by age 75 being affected. This condition occurs after years of exposure to intense noise levels, leading to the loss or damage of nerve hair cells within the cochlea. Men are more likely to develop hearing loss due to their higher likelihood of working in noisy environments (NIDCD, n.d.). Smoking, high blood pressure, and stroke can exacerbate hearing loss, with high-frequency sounds being the first to be affected. To prevent hearing loss, avoiding exposure to boisterous environments is essential.

Weight gain is one of the most common complaints of middle-aged adults, with many experiencing what is known as the “middle-aged spread” or the accumulation of fat in the abdomen. Men accumulate fat on their upper abdomen and back, while women get more fat on their waist and upper arms. The metabolism slows by about one-third during midlife, so many middle-aged adults are surprised by the weight gain despite eating the same diet (Berger, 2005). To maintain their earlier physique, midlife adults need to increase their level of exercise, eat less, and watch their nutrition.

Most changes during midlife can be easily compensated for, such as buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats. However, the percentage of adults who have a disability increases through midlife. While 7 percent of people in their early 40s have a disability, the rate jumps to 30 percent by the early 60s. Those of lower socioeconomic status are likelier to experience such an increase (Bumpass & Aquilino, 1995).

What Can We Conclude from This Information?

How we live our lives can significantly impact our health, especially during midlife. Habits such as smoking, drinking, unhealthy eating, stress, lack of physical exercise, and chronic illnesses like diabetes or arthritis can all reduce our overall health. Therefore, midlife adults must take preventative measures to improve their physical well-being. Those with a strong sense of control over their lives, engaging in challenging physical and mental activities, participating in weight-bearing exercises, monitoring their nutrition, and using social resources are most likely to enjoy good health throughout these years. According to Saint-Maurice et al. (2019), even those who begin exercising in their 40s can enjoy the same benefits as those who started in their 20s. Additionally, it’s never too late to begin, and maintaining healthy habits is just as crucial as starting them in the first place.

What Are Some Normal Physiological Changes in Middle Adulthood?

The Climacteric

One of the biological changes that occurs during midlife is known as the climacteric. It is a period where men may experience a reduction in their reproductive ability, while women lose their capacity to reproduce completely after reaching menopause. The climacteric is a natural process that marks the end of the reproductive phase of human life.

Menopause

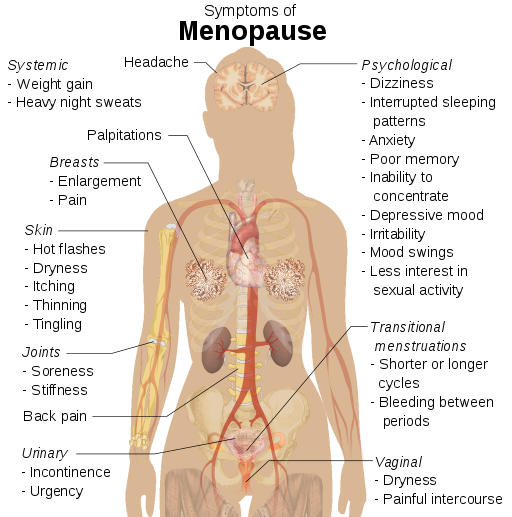

Menopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs, and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases (Figure 9.1). After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (National Institution of Health, 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid-40s and mid-50s. The median age range for a woman to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication, which diminishes and becomes waterier. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner and less elastic.

Menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004). Changes in hormone levels are associated with hot flashes and sweats in some women, but women vary in the extent to which these are experienced. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are not necessarily due to menopause (Rossi, 2019). Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not. The incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women.

Cultural influences impact how menopause is experienced. For example, a classroom study found that after listing the symptoms of menopause in a psychology course, a woman from Kenya responded that those symptoms are not prevalent in her country, which represents cultural variations in menopausal symptoms. Another example shows that hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending on their expectations for themselves and their lives. African-American and Mexican-American women, in association with White women who are career-focused overall, tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a widespread tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Andropause

Do Males Experience a Climacteric?

Yes. While they do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, they tend to produce lower testosterone levels and fewer sperm. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life after puberty. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of low levels of testosterone.

Low levels of testosterone result in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. This decrease in libido and lower testosterone (androgen) levels is known as andropause, although this term is somewhat controversial as this experience is not delineated, as menopause is for women. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular diseases such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be tested; if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long-term HRT (Hormone Replacement Therapy) for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (Patient Education Institution, n.d.).

The debate around declining testosterone levels in men may hide a fundamental fact. The issue is not about individual males experiencing individual hormonal changes at all. We have all seen adverts on the media promoting substances to boost testosterone: “Is it low-T?” The answer is probably in the affirmative, if somewhat relative. That is, in all likelihood, they will have lower testosterone levels than their fathers. However, it is equally likely that the issue does not lie solely in their physiological makeup but is rather a generational transformation (Travison et al., 2007). Why this has occurred in such a dramatic fashion is still unknown. There is evidence that low testosterone may have adverse health effects on men. In addition, some studies show evidence of rapidly decreasing sperm count and grip strength. Exactly why these changes are happening is unknown and will likely involve more than one cause.

Exercise, Nutrition, and Health

The Impact of Exercise

Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults exercise, and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Many stop exercising soon after they begin an exercise program—particularly those who are very overweight. The best exercise programs are engaged regularly—regardless of the activity, but a well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make a difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Exercise is beneficial in reducing stress in midlife. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors, and learning relaxation techniques can have healthful benefits. Exercise can be considered preventative healthcare; promoting exercise for the 78 million “baby boomers” may be one of the best ways to reduce healthcare costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998).

Nutrition

Aging brings about a reduction in the number of calories a person requires. Many Americans respond to weight gain by dieting. However, eating less does not necessarily mean eating right; people often suffer from vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Very often, physicians will recommend vitamin supplements to their middle-aged patients. As stated above, chronic inflammation is now identified as one of the so-called “pillars of aging.” The link between diet and inflammation is yet unclear, but there is now some information available on the Diet Inflammation Index (Shivappa et al., 2014), which, in popular parlance, supports a diet rich in plant-based foods, healthy fats, nuts, fish in moderation, and sparing use of red meat. The ideal diet is one low in fat, low in sugar, high in fiber, low in sodium, and low in cholesterol.

Health Concerns

Heart Disease: According to the most recent National Vital Statistics Reports (Xu et al., 2016), heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death for Americans, with 23.5% of those who died in 2013. It is also the number one cause of death globally, according to the World Health Organization. (WHO, 2013). Heart disease develops slowly over time and typically appears in midlife (Hooker and Pressman, 2016).

Heart disease can include heart defects and heart rhythm problems, as well as narrowed, blocked, or stiffened blood vessels, referred to as cardiovascular disease. The blocked blood vessels prevent the body and heart from receiving adequate blood. Atherosclerosis, or a buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, is the most common cause of cardiovascular disease. The plaque buildup thickens the artery walls and restricts the blood flow to organs and tissues. Cardiovascular disease can lead to a heart attack, chest pain (angina), or stroke (Mayo Clinic, 2014).

Symptoms of cardiovascular disease differ for men and women. Males are more likely to suffer chest pain, while women are more likely to demonstrate shortness of breath, nausea, and extreme fatigue. Symptoms can also include pain in the arms, legs, neck, jaw, throat, abdomen, or back (Mayo Clinic, 2014). According to the Mayo Clinic (2014), there are many risk factors for developing heart disease, including medical conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity.

Other risk factors include:

- Advanced Age—increases the risk of narrowed arteries and weakened or thickened heart muscle.

- Males are at greater risk, but a female’s risk increases after menopause.

- Family History—increased risk, especially if a male parent or brother developed heart disease before age 55 or a female parent or sister developed heart disease before age 65.

- Smoking—nicotine constricts blood vessels, and carbon monoxide damages the inner lining.

- Poor Diet—a diet high in fat, salt, sugar, and cholesterol.

- Stress—unrelieved stress can damage arteries and worsen other risk factors.

- Poor Hygiene—establishing good hygiene habits can prevent viral or bacterial infections that can affect the heart. Poor dental care can also contribute to heart disease.

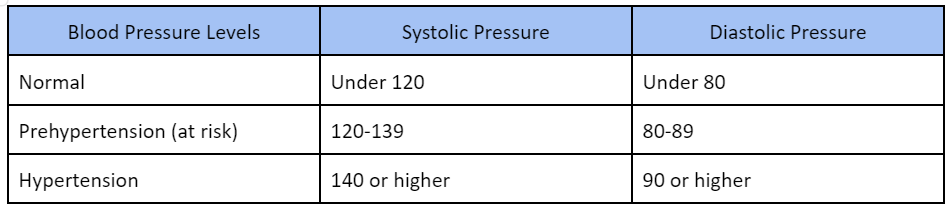

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a serious health problem when the blood flows with a greater force than usual. One in three American adults (70 million people) has hypertension, and only half have it under control (Nwankwo et al., 2013). It can strain the heart, increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, or damage the kidneys (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). In early and middle adulthood, uncontrolled high blood pressure can also damage the brain’s white matter (axons) and may be linked to cognitive problems later in life (Maillard, 2012). Normal blood pressure is under 120/80 (see Table 1). The first number is the systolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart beats. The second number is the diastolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart is at rest. High blood pressure is sometimes referred to as the silent killer, as most people with hypertension experience no symptoms.

Risk factors for high blood pressure include:

- Family history of hypertension

- A diet that is too high in sodium, often found in processed foods, and too low in potassium.

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Obesity

- Too much alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use, as nicotine raises blood pressure (CDC, 2014)

Making lifestyle changes can often reduce blood pressure in many people.

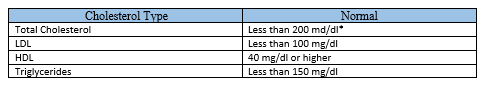

Cholesterol is a waxy, fatty substance carried by lipoprotein molecules in the blood. It is created by the body to create hormones and digest fatty foods and is also found in many foods. Your body needs cholesterol, but too much can cause heart disease and stroke. Two important kinds of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). A third type of fat is called triglycerides. Your total cholesterol score is based on all three types of lipids (see Table 3). Total cholesterol is calculated by adding HDL plus LDL plus 20% of the Triglycerides.

Table 9.3. Normal Levels of Cholesterol

Risk factors for high cholesterol include a family history of high cholesterol, diabetes, a diet high in saturated fats, trans fats, and cholesterol, physical inactivity, and obesity. Almost 32% of American adults have high LDL cholesterol levels, and the majority do not have it under control or have made lifestyle changes.

Diabetes (Diabetes Mellitus) is a disease in which the body does not control the amount of glucose in the blood. This disease occurs when the body does not make enough insulin or use it as it should (National Institutions of Health, 2016). Insulin is a hormone that helps glucose in the blood enter cells to give them energy. In adults, 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes are type 2 (American Diabetes Association, 2014). Type 2 diabetes usually begins with insulin resistance, a disorder in which the muscles, liver, and fat tissue cells do not use insulin properly (CDC, 2014). As the need for insulin increases, cells in the pancreas gradually lose the ability to produce enough insulin. In some type 2 diabetics, pancreatic beta cells will cease functioning, and insulin injections will become necessary. Some people with diabetes experience insulin resistance with only minor dysfunction of the beta cell secretion of insulin. Other diabetics experience only slight insulin resistance, with the primary cause being a lack of insulin secretion (CDC, 2014).

Diabetes also affects ethnic and racial groups differently. Non-Hispanic Whites (7.6%) are less likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than Asian Americans (9%), Hispanics (12.8%), non-Hispanic Blacks (13.2%), and American Indians/Alaskan Natives (15.9%). However, these general figures hide the variations within these groups. For instance, the rate of diabetes was less for Central, South, and Cuban Americans than for Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans and four times less for Alaskan Natives than the American Indians of southern Arizona (CDC, 2014).

The risk factors for diabetes include:

- Those over age 45

- Obesity

- Family history of diabetes

- History of gestational diabetes (see Chapter 2)

- Race and ethnicity

- Physical inactivity

- Diet

Sleep problems: According to the Sleep in America (2015) poll, 9% of Americans report being diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and of those, 71% have sleep apnea, and 24% suffer from insomnia. Pain also contributes to the difference between the amount of sleep Americans need and the amount they get. An average of 42 minutes of sleep debt occurs for those with chronic pain and 14 minutes for those who have suffered from acute pain in the past week. Stress and poor health are vital to shorter sleep durations and worse sleep quality. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced more significant sleep onset delay than those with higher life satisfaction. Delayed onset of sleep could result from worry and anxiety during midlife, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep. Lastly, menopause can affect a woman’s sleep duration and quality (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

Cancer

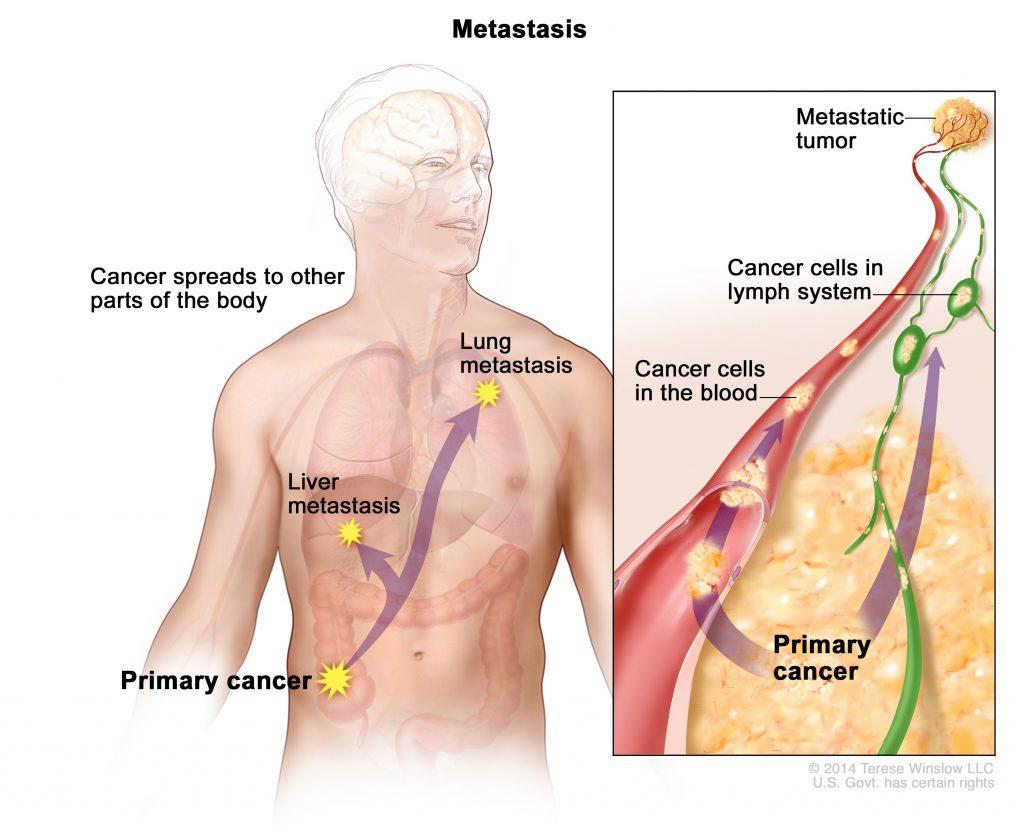

After heart disease, cancer was the second leading cause of death for Americans in 2013, accounting for 22.5% of all deaths (Xu et al., 2016). According to the National Institutes of Health (2015), cancer is the name given to a collection of related diseases in which the body’s cells begin to divide without stopping and spread into surrounding tissues. These extra cells can divide and form growths called tumors, which are typically masses of tissue. Cancerous tumors are malignant, which means they can invade nearby tissues. When removed, malignant tumors may grow back. Unlike malignant tumors, benign tumors do not invade nearby tissues. Benign tumors can sometimes be quite large and, when removed, usually do not grow back. Although benign tumors in the body are not cancerous, benign brain tumors can be life-threatening.

Cancer cells can prompt nearby normal cells to form blood vessels that supply the tumors with oxygen and nutrients allowing them to grow. These blood vessels also remove waste products from the tumors. Cancer cells can also hide from the immune system, a network of organs, tissues, and specialized cells that protect the body from infections and other conditions. Lastly, cancer cells can metastasize, which means they can break from where they first formed, called primary cancer, and travel through the lymph system or blood to form new tumors in other body parts. This new metastatic tumor is the same type as the primary tumor (National Institutes of Health, 2015).

What Types of Cognitive Development Are Experienced during Middle Adulthood?

While we sometimes associate aging with cognitive decline (often due to how it is portrayed in the media), aging does not necessarily mean decreased cognitive function. Tacit knowledge, verbal memory, vocabulary, inductive reasoning, and other practical thought skills increase with age. We’ll learn about these advances and some neurological changes in middle adulthood in the following section (Lumen Learning, n.d.). The cognitive mechanics of processing speed, often called fluid intelligence, physiological lung capacity, and muscle mass, are in relative decline. However, knowledge, experience, and the increased ability to regulate emotions can compensate for these losses. Continuing cognitive focus and exercise can also reduce the extent and effects of cognitive decline. There is some evidence that adults should be as aggressive in maintaining their mental health as they are in their physical health during this time, as the two are intimately related.

Control Beliefs

Central to this are personal control beliefs, which have a long history in psychology. Empirical research has shown that those with an internal locus of control enjoy better results in behavioral, motivational, and cognitive psychological tests across the board. It is reported that this belief in control declines with age, but again, there is a great deal of individual variation. This raises another issue: directional causality. Does my belief in my ability to retain my intellectual skills and abilities at this time of life ensure better performance on a cognitive test than those who believe in their inexorable decline? Or does the fact that I enjoy that intellectual competence or facility instill or reinforce that belief in control and controllable outcomes? It is not clear which factor is influencing the other. The exact nature of the connection between control beliefs and cognitive performance remains unclear (Lachman et al., 2014).

Brain science is developing exponentially and will unquestionably deliver new insights on various cognition-related issues in midlife. One of them will surely be on the brain’s capacity to renew, or at least replenish itself, at this time of life. The ability to restore is called neurogenesis; the capacity to fill what is there is called neuroplasticity. At this stage, it is impossible to ascertain what effect future pharmacological interventions may have on the possible cognitive decline at this and later stages of life.

Cognitive Aging

Researchers have identified areas of loss and gain in cognition in older age. Cognitive ability and intelligence are often measured using standardized tests and validated measures. The psychometric approach has identified two categories of intelligence that show different rates of change across the lifespan(Schaie & Willis, 1996). Fluid and crystallized intelligence were first identified by Cattell in 1971. Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge.

Heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and age influence intelligence. One distinction in specific intelligence noted in adulthood is between fluid intelligence, which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly, and crystallized intelligence, which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligences are distinct; crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence decreases.

Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts. There is a general acceptance that fluid intelligence has decreased continually since the 20s but that crystallized intelligence continues to accumulate. One might expect to complete an extensive crossword more quickly at 48 than 22, but the capacity to deal with novel information declines.

With age, systematic declines are observed in cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing without supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). Older adults tend to perform poorer than young adults on memory tasks that involve recall of information, where individuals must retrieve information they learned previously without the help of a list of possible choices. For example, older adults may have more difficulty recalling facts such as names or contextual details about where or when something happened (Craik, 2000). What might explain these deficits as we age?

As we age, working memory, or our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences in many cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on specific information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognizing memory tasks or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well, if not better, than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. Age usually comes with expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, more senior chess experts can focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults make better decisions than young adults (Tentori et al., 2001).

Watch It

This video highlights cognitive changes during adulthood and the characteristics that either decline, improve, or remain stable.

Performance in Middle Adulthood

Research on interpersonal problem-solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform less well on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise like everyday problem-solving to compensate for cognitive decline.

Given their nature, empirical studies of cognitive aging are often tricky and technical. Similarly, experiments focused on one task may tell you little about general capacities. Memory and attention as psychological constructs are now divided into specific subsets, which can be confusing and difficult to compare.

However, one study does show with relative clarity the issues involved. In the USA, the Federal Aviation Authority insists that all air traffic controllers retire at 56 and cannot begin until age 31 unless they have previous military experience. However, in Canada, controllers are allowed to work until age 65 and are allowed to train at a much earlier age. Nunes and Kramer (2009) studied four groups: a younger group of controllers (20-27), an older group of controllers aged 53 to 64, and two other groups of the same age who were not air traffic controllers. Older controllers were slower than their younger peers on simple cognitive tasks unrelated to their occupational lives as controllers. However, when it came to job-related tasks, their results were essentially identical. This was not true of the older group of non-controllers, who had significant deficits in comparison. Specific knowledge or expertise in a domain acquired over time (crystallized intelligence) can offset a decline in fluid intelligence.

Tacit Knowledge

The idea of tacit knowledge was first introduced by Michael Polanyi in 1967. Tacit knowledge is pragmatic or practical knowledge learned through experience rather than explicitly taught, and it also increases with age (Hedlund et al., 2002). Tacit knowledge might be considered “know-how” or “professional instinct.” It is called tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge, but rather, it consists of using skills and problem-solving in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be understood in the workplace and used by blue-collar workers, such as carpenters, chefs, and hairdressers.

Think of someone you have encountered who is extremely good at what they do. They may have no more (or less) education, formal training, and experience than others who are supposedly at an equivalent level. What is the “something” that they have? Tacit knowledge is highly prized, and older workers often have the most significant amount, even if they are not conscious of that fact.

Middle Adults Returning to Education

Midlife adults in the United States often find themselves in college classrooms. The enrollment rate for older Americans entering college, often part-time or in the evenings, is rising faster than traditionally aged students. Students over age 35 accounted for 17% of all college and graduate students in 2009 and are expected to comprise 19% by 2020 (Holland, 2014). According to the American Association of Community Colleges (2022), students aged 22-39 make up 36% of enrollments, whereas those aged 40+ make up 8%. In some cases, older students are developing skills and expertise to launch a second career or to take their career in a new direction. Whether they enroll in school to sharpen particular skills, to retool and reenter the workplace, or to pursue interests that have previously been neglected, older students tend to approach the learning process differently than younger college students (Knowles et al., 1998).

The mechanics of cognition, such as working memory and processing speed, gradually decline with age. However, they can be easily compensated for through higher-order cognitive skills, such as forming strategies to enhance memory or summarizing and comparing ideas rather than relying on rote memorization (Lachman, 2004). Although older students may take longer to learn the material, they are less likely to forget it quickly. Adult learners tend to look for relevance and meaning when learning information. Older adults have the most challenging time learning meaningless or unfamiliar material. They are more likely to ask themselves, “Why is this important?” when being introduced to information or trying to memorize concepts or facts. Older adults are more task-oriented learners and want to organize their activities around problem-solving. However, these differences may decline as new generations of higher education enter midlife.

What Are Some Psychosocial Experiences That Occur during Middle Adulthood?

In popular culture and academic literature, middle adulthood is often associated with a “midlife crisis,” an emotional struggle with identity and self-confidence that can occur in early middle age. There is an emerging view that this may have been an overstatement—indeed, the evidence on which it is based has been seriously questioned. However, there is some support for the view that people do undertake a sort of emotional audit, reevaluate their priorities, and emerge with a slightly different orientation to emotional regulation and personal interaction at this time. Why and the mechanisms through which this change is affected are a matter of debate. We will examine the ideas of Erikson, Baltes, and Carstensen and how they might inform a more nuanced understanding of this vital part of the lifespan (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

What do you think is the happiest stage of life (Lumen Learning, n.d.)? What about the saddest stages? Perhaps surprisingly, Blanchflower & Oswald (2008) found that reported levels of unhappiness and depressive symptoms peak in the early 50s for men in the U.S. and, interestingly, in the late 30s for women. In Western Europe, minimum happiness is reported around the mid-40s for both men and women, albeit with some significant national differences. There is now a view that “older people” (50+) may be “happier” than younger people despite some cognitive and functional losses. This is often referred to as “the paradox of aging.” Positive attitudes to the continuance of mental and behavioral activities, interpersonal engagement, and their vitalizing effect on human neural plasticity may lead to more life and an extended period of self-satisfaction and continued communal engagement.

Erikson’s Theory

As you know by now, Erikson’s theory is based on epigenesis, meaning that development is progressive and that each individual must pass through the eight different stages of life—all while being influenced by context and environment. Each stage forms the basis for the following stage, and each transition to the next is marked by a crisis that must be resolved. The sense of self, each “season,” was wrested from by that conflict. The ages 40-65 are no different. The individual is still driven to engage productively, but nurturing children and income generation assume lesser functional importance. From where will the individual derive their sense of self and self-worth?

Generativity versus stagnation is Erikson’s characterization of the fundamental conflict of adulthood. It is the seventh conflict of his famous “8 Seasons of Man” (1950), and negotiating this conflict results in the virtue of care. Generativity is “primarily concerned with establishing and guiding the next generation.” Generativity concerns a generalized other (as well as those close to an individual) and occurs when a person can shift their energy to care for and mentor the next generation. One apparent motive for this generative thinking might be parenthood, but others have suggested intimations of mortality by the self. John Kotre (1950) theorized that generativity is selfish, stating that its fundamental task was to outlive the self. He viewed generativity as a form of investment. This form of investment can often be seen through volunteering. However, a commitment to a “belief in the species” can be taken in numerous directions, and it is probably correct to say that most modern treatments of generativity treat it as a collection of facets or aspects—encompassing creativity, productivity, commitment, interpersonal care, and so on.

On the other side of generativity is stagnation, which refers to lethargy and a lack of enthusiasm and involvement in individual and communal affairs. It may also denote an underdeveloped sense of self or some form of overblown narcissism. Erikson sometimes used the word “rejectivity” when referring to severe stagnation.

Watch It

This video explains the midlife crisis.

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST)

It is the inescapable fate of human beings to know that their lives are limited. As people move through life, goals and values tend to shift. What we consider priorities, goals, and aspirations are subject to renegotiation. Attachments to others, current and future, are no different. Time is not the unlimited good perceived by a child under normal social circumstances; it is very much a valuable commodity, requiring careful consideration in terms of the investment of resources. This has become known in academic literature as mortality salience.

Mortality salience posits that reminders about death or finitude (at either a conscious or subconscious level) fill us with dread. We seek to deny its reality, but awareness of the increasing nearness of death can potentially affect human judgment and behavior. This has become a critical concept in contemporary social science. With this understanding, Laura Carstensen developed the socioemotional selectivity theory, or SST. The SST maintains that as time horizons shrink, as they typically do with age, people become increasingly selective, investing more significant resources in emotionally meaningful goals and activities. According to the theory, motivational shifts also influence cognitive processing. Aging is associated with a relative preference for positive over negative information. This selective narrowing of social interaction maximizes positive emotional experiences and minimizes emotional risks as individuals age. They systematically hone their social networks so that available social partners satisfy their emotional needs. An adaptive way of maintaining a positive effect might be to reduce contact with those we know may negatively affect us and avoid those who might.

Watch It

Watch Laura Carstensen explain how happiness increases with age.

Transcript for “Older people are happier – Laura Carstensen.”

Selection, Optimization, Compensation (SOC)

Another perspective on aging was identified by German developmental psychologists Paul and Margret Baltes. Their text Successful Aging (1990) marked a seismic shift in moving social science research on aging from a broadly deficits-based perspective to a newer understanding based on a holistic life course. The former focused exclusively on what was lost during the aging process rather than seeing it as a balance between those losses and gains in areas like regulating emotion, experience, and wisdom.

The Baltes’ model for successful aging argues that people face various opportunities or challenges across the lifespan, such as jobs, educational opportunities, and illnesses. According to the SOC model, a person may select particular goals or experiences, or circumstances might impose themselves on them. Either way, the selection process includes shifting or modifying goals based on choice or circumstance in response to those circumstances.

The change in direction may occur at the subconscious level. This model emphasizes that setting goals and directing efforts towards a specific purpose benefit healthy aging. Optimization is about making the best use of our resources to pursue goals. Compensation, as its name suggests, is about using alternative strategies to attain those goals (Baltes & Baltes, 1990).

The selection, optimization, and compensation processes can be found throughout the lifespan. As we progress in years, we select areas where we place resources, hoping that this selection will optimize our resources and compensate for any defects accruing from physiological or cognitive changes. The work of Paul and Margaret Baltes was very influential in forming a comprehensive developmental perspective that would merge around the central idea of resiliency (Weiss, Westerhof & Bohmeijer, 2016).

The SOC model covers several functional domains—motivation, emotion, and cognition. We might become more adept at playing the SOC game as time passes, as we work to compensate and adjust for changing abilities across the lifespan.

Stress

Social Relationships and Stress

Research has shown that the impact of social isolation on our risk for disease and death is similar in magnitude to the risk associated with smoking regularly (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). The importance of social relationships for our health is so significant that some scientists believe our body has developed a physiological system that encourages us to seek out our relationships, especially in times of stress (Taylor et al., 2000). Social integration is the concept used to describe the number of social roles you have (Cohen & Willis, 1985).

Maintaining these different roles can improve your health by encouraging those around you to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Those in your social network might also provide you with social support (e.g. when you are under stress). This support might include emotional help (e.g., a hug when needed), tangible help (e.g., lending money), or advice. By helping to improve health behaviors and reduce stress, social relationships can have a powerful, protective impact on health and, in some cases, might even help people with serious illnesses stay alive longer (Spiegel et al., 1989).

Caregiving and Stress

A disabled child, spouse, parent, or other family member is part of the lives of some midlife adults. According to the National Alliance for Caregiving (2015), 40 million Americans provide unpaid caregiving. The typical caregiver is a 49-year-old female currently caring for a 69-year-old female who needs care because of a long-term physical condition. Looking more closely at the age of the recipient of caregiving, the typical caregiver for those 18-49 years of age is a female (61%), mainly caring for her child (32%), followed by a spouse or partner (17%). When looking at older recipients (50+) who receive care, the typical caregiver is female (60%) caring for a parent (47%) or spouse (10%).

Caregiving places enormous stress on the caregiver. Caregiving for a young or adult child with special needs was associated with poorer global health and more physical symptoms among both fathers and mothers (Seltzer et al., 2011). Marital relationships are also a factor in how caring affects stress and chronic conditions. Fathers who were caregivers identified more chronic health conditions than non-caregiving fathers, regardless of marital quality. In contrast, caregiving mothers reported higher levels of chronic conditions when they reported a high level of marital strain (Kang & Marks, 2014). Age can also affect how one is affected by the stress of caring for a child with special needs. Using data from the Study of Midlife in the United States, Ha, Hong, Seltzer, and Greenberg (2008) found that older parents were significantly less likely to experience the adverse effects of having a disabled child than younger parents. They concluded that an age-related weakening of the stress occurred over time. This is followed by the greater emotional stability noted at midlife.

Currently, 25% of adult children, mainly baby boomers, provide personal or financial care to a parent (Metlife, 2011). Daughters are more likely to provide primary care, and sons are more likely to provide financial assistance. Adult children 50+ who work and provide care to a parent are more likely to have fair or poor health when compared to those who do not provide care. Some adult children choose to leave the workforce. However, the cost of leaving the workforce early to care for a parent is high. For females, lost wages and social security benefits equals $324,044, while for men, it equals $283,716 (Metlife, 2011). This loss can jeopardize the adult child’s financial future. Consequently, there is a need for greater workplace flexibility for working caregivers.

Spousal Care

Indeed, caring for a disabled spouse would be a demanding experience that could negatively affect one’s health. However, research indicates that there can be positive health effects for caring for a disabled spouse. Beach, Schulz, Yee, and Jackson (2000) evaluated health-related outcomes in four groups: Spouses with no caregiving needed (Group 1), living with a disabled spouse but not providing care (Group 2), living with a disabled spouse and providing care (Group 3), and helping a disabled spouse while reporting caregiver strain, including elevated levels of emotional and physical stress (Group 4). Not surprisingly, the participants in Group 4 were the least healthy and identified poorer perceived health, an increase in health-risk behaviors, and an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms. However, those in Group 3 who provided care for a spouse but did not identify caregiver strain identified decreased levels of anxiety and depression compared to Group 2 and were similar to those in Group 1. It appears that greater caregiving involvement was related to better mental health as long as the caregiving spouse did not feel the strain. The beneficial effects of helping identified by the participants were consistent with previous research (Schulz et al., 1997).

When caring for a disabled spouse, gender differences have also been identified. Female caregivers of a spouse with dementia experienced more burden, had poorer mental and physical health, exhibited increased depressive symptomatology, took part in fewer health-promoting activities, and received fewer hours of help than male caregivers (Gibbons et al., 2014). This recent study was consistent with previous research findings that women experience more caregiving burden than men despite similar caregiving situations (Yeager et al., 2010). Explanations for why women do not use more external support, which may alleviate some of the burden, include women’s expectations that they should assume caregiving roles (Torti et al., 2004) and their concerns with the opinions of others (Arai, 2000). Also contributing to women’s poorer caregiving outcomes is that disabled males are more aggressive than females, especially males with dementia, who display more physical and sexual aggression toward their caregivers (Zuidema, 2009). Female caregivers are certainly at risk for adverse consequences of caregiving, and greater support needs to be available to them.

Working in Midlife

The U.S. workforce consists of civilian, non-institutionalized individuals aged 16 and older who are employed. Since the late 1990s, the percentage of the population in the workforce has been steadily declining. In 1999, the percentage of employed people peaked at 67%. However, by 2012, it had dropped to 64%; as of 2021, it had further decreased to 58% (Monthly Labor Review, 2021). It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has also impacted these figures.

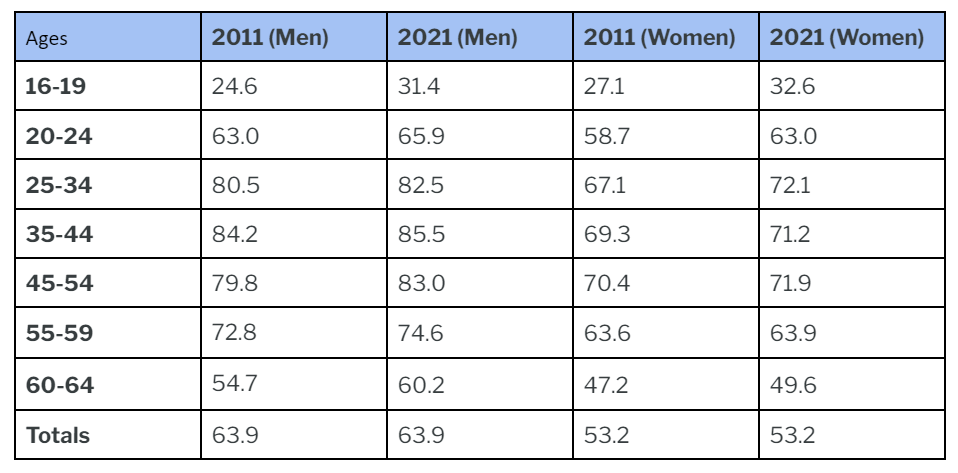

Additionally, there has been an increase in the percentage of the population aged 55 and above. In 1992, this percentage was 26%, which grew to 29.3% in 2019. This figure is projected to rise to 32.6% by 2040 (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2017). The table below shows the employment rates by age, and as of 2021, approximately 64% of the workforce is male. The participation rate in the labor force has improved for both genders and age groups from 2011 to 2021.

Table 9.5 – Percentage of the non-institutionalized civilian workforce employed by gender & age.

Adapted from Monthly Labor Review, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cps/tables.htm#otheryears

What Is the Climate in the Workplace for Middle-Aged Adults?

Several studies have found job satisfaction peaks in middle adulthood (Besen et al., 2013). This satisfaction stems from higher wages and often greater involvement in decisions that affect the workplace as they move from worker to supervisor or manager. Job satisfaction is also influenced by being able to do the job well, and after years of experience at a job, many people are more effective and productive. Another reason for this peak in job satisfaction is that at midlife, many adults lower their expectations and goals (Tangri, Thomas, & Mednick, 2003). Middle-aged employees may realize they have reached the highest they are likely to in their careers. This satisfaction at work translates into lower absenteeism, greater productivity, and less job hopping compared to younger adults (Easterlin, 2006).

However, not all middle-aged adults are happy in the workplace. Women may find themselves up against the glass ceiling of organizational discrimination in the workplace that limits their career advancement. This may explain why females employed at large corporations are twice as likely to quit their jobs as men (Barreto, Ryan, & Schmitt, 2009). Another problem older workers may encounter is job burnout, becoming disillusioned and frustrated at work. American workers may experience more burnout than workers in many other developed nations because most developed nations guarantee a set number of paid vacation days by law (International Labor Organization, 2011). In contrast, the United States does not (U.S. Dept. of Labor, 2016).

What Are the Challenges in the Workplace for Middle-Aged Adults?

In recent years, middle-aged adults have been challenged by economic downturns, starting in 2001 and again in 2008. Fifty-five percent of adults reported some problems in the workplace, such as fewer hours, pay cuts, having to switch to part-time, etc., during the most recent economic recession (see Figure) (Pew Research Center, 2010a). While young adults took the biggest hit in terms of levels of unemployment, middle-aged adults also saw their overall financial resources suffer as their retirement nest eggs disappeared. House values shrank while foreclosures increased (Pew Research Center, 2010).

Not surprisingly, this age group reported that the recession hit them worse than other age groups, especially those aged 50-64. Middle-aged adults who find themselves unemployed are likely to remain unemployed longer than those in early adulthood (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2012). In the eyes of employers, it may be more cost-effective to hire a young adult, despite their limited experience, as they would be starting at lower levels of the pay scale. In addition, hiring someone who is 25 and has many years of work ahead of them versus someone who is 55 and will likely retire in 10 years may also be part of the decision to hire a younger worker (Lachman, 2004). American workers are also competing with global markets and changes in technology. Those who can keep up with all these changes or are willing to uproot and move around the country or even the world have a better chance of finding work. The decision to move may be more accessible for younger people who have fewer obligations to others.

Do Midlifers Enjoy Leisure Time?

As most developed nations restrict the number of hours an employer can demand that an employee work per week and require employers to offer paid vacation time, what do middle-aged adults do with their time off from work and duties, referred to as leisure? Around the world, watching television is the most common leisure activity in early and middle adulthood (Marketing Charts Staff, 2014). On average, middle-aged adults spend 2-3 hours per day watching TV (Gripsrud, 2007), and watching TV accounts for more than half of all leisure time.

In the United States, men spend about 5 hours more per week in leisure activities, especially on weekends, than women (Drake, 2013). The leisure gap between mothers and fathers is slightly smaller, about 3 hours a week, than among those without children under age 18 (Drake, 2013). Those aged 35-44 spend less time on leisure activities than any other age group, 15 or older (Drake, 2013). This is unsurprising as this age group is more likely to be parents and still working up their career ladder, so they may feel they have less time for leisure.

Americans have less leisure time than people in many other developed nations. As you read earlier, there are no laws in many job sectors guaranteeing paid vacation time in the United States. Ray, Sanes, and Schmitt (2013) report that several other nations also provide additional time off for young and older workers and shift workers. In the United States, those in higher-paying jobs and those covered by a union contract are likelier to have paid vacation time and holidays (Ray, Sanes, Schmitt, 2013).

What Are the Benefits of Taking Time Away from Work?

Several studies have noted the benefits of taking time away from work. It reduces job stress burnout and improves mental and physical health, mainly if that leisure time includes moderate physical activity. Leisure activities can also improve productivity and job satisfaction and help adults balance family and work obligations. (Project Time-Off, 2016).

What Do Relationships Look Like During Middle Adulthood?

The importance of establishing and maintaining relationships in middle adulthood is well-established in the academic literature. There are now thousands of published articles purporting to demonstrate that social relationships are integral to any aspect of subjective well-being and physiological functioning, and these help to inform actual healthcare practices. Studies show an increased risk of dementia, cognitive decline, susceptibility to vascular disease, and increased mortality in those who feel isolated and alone. However, loneliness is not confined to people living a solitary existence. It can also refer to those who endure a perceived discrepancy in the socio-emotional benefits of interactions with others, either in number or nature. One may have an expansive social network and still feel a dearth of emotional satisfaction in one’s own life (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Relationship Types

Intimate Relationships

It makes sense to consider the various relationships in our lives to determine how relationships impact our well-being. For example, would you expect someone to derive the same happiness from an ex-spouse as a child or coworker? Among the most critical relationships for most people is their long-time romantic partner. Most researchers begin their investigation of this topic by focusing on intimate relationships because they are the closest form of social bonds. Intimacy is more than physical; it also entails psychological closeness. Research findings suggest that having a single confidante—someone with whom you can be authentic and trust not to exploit your secrets and vulnerabilities—is more important to happiness than having an extensive social network (Taylor, 2010).

Another important aspect is the distinction between formal and informal relationships. Formal relationships are those that are bound by the rules of politeness. In most cultures, for instance, young people treat older people with formal respect by avoiding profanity and slang when interacting with them. Similarly, workplace relationships tend to be more formal, as do relationships with new acquaintances. Formal connections are generally less relaxed because they require more work, demanding that we exert more self-control. Contrast these connections with informal relationships—friends, lovers, siblings, or others with whom you can relax. We can express our true feelings and opinions in these informal relationships, using the language that comes most naturally to us, and generally be more authentic. Because of this, it makes sense that more intimate relationships—those that are more comfortable and in which you can be more vulnerable—might be the most likely to translate to happiness.

Parenting in Later Life

Just because children grow up does not mean their family stops being a family. Instead, the specific roles and expectations of its members change over time. One significant change comes when a child reaches adulthood and moves away. When exactly children leave home varies greatly depending on societal norms and expectations, as well as on economic conditions such as employment opportunities and affordable housing options. Some parents may experience sadness when their adult children leave the home—a situation called an empty nest.

Many parents also find that their grown children are struggling to become independent. It’s an increasingly common story: a child goes off to college and, upon graduation, cannot find steady employment. In such instances, a frequent outcome is for the child to return home, becoming a “boomerang kid.” As the phenomenon has come to be known, the boomerang generation refers to young adults, mainly between the ages of 25 and 34, who return home to live with their parents. At the same time, they strive for stability in their lives—often in terms of finances, living arrangements, and sometimes romantic relationships. These boomerang kids can be both good and bad for families. Within American families, 48% of boomerang kids report paying their parents rent, and 89% say they help with household expenses—a win for everyone (Parker, 2012).

On the other hand, 24% of boomerang kids report that returning home hurts their relationship with their parents (Parker, 2012). For better or worse, the number of children returning home has been increasing worldwide. The Pew Research Center (2016) reported that the most common living arrangement for people aged 18-34 was living with their parents (32.1%) (Fry, 2016).

Family Issues and Considerations

In addition to middle-aged parents spending more time, money, and energy taking care of their adult children, they are also increasingly taking care of their aging and ailing parents. Middle-aged people in this set of circumstances are commonly called the sandwich generation. They are still looking out for their children while simultaneously caring for elderly parents (Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2015). Of course, cultural norms and practices again come into play. In some Asian and Hispanic cultures, the expectation is that adult children are supposed to take care of aging parents and parents-in-law. In other Western cultures—cultures that emphasize individuality and self-sustainability—the expectation has historically been that elders either age in place, modify their homes, and receive services to allow them to continue to live independently or enter long-term care facilities. However, given financial constraints, many families take in and care for their aging parents, increasing the number of multigenerational homes worldwide.

As a midlife child, you may take on various responsibilities such as organizing family events, managing communication, and maintaining family ties. This role was first defined by Carolyn Rosenthal in 1985. Typically, kinkeepers are midlife daughters coordinating family gatherings, such as telling everyone what food to bring or arranging a family reunion.

Kinkeeping can be seen as a managerial role that helps to sustain family connections and lines of communication. This applies to many families, including large nuclear, reconstituted, and multi-generational families. Rosenthal discovered that over half of the families she surveyed could identify the person who takes on this role.

Usually, adults at this stage are required to shoulder caregiving responsibilities. With increasing costs of professional care for the elderly and shifts in longevity, this role is likely to grow, which could place even greater pressure on careers.

Singlehood

According to a recent study by Pew Research, 16 out of 1,000 adults aged 45 to 54 in the U.S. have never been married, while 7 out of 1,000 adults aged 55 and older have never been married. However, some individuals may live with a partner, while others may be single due to divorce or widowhood. Bella DePaulo has challenged the notion that singles, particularly those who have always been single, are worse off emotionally and in terms of health compared to their married counterparts.

DePaulo suggests that studies examining the benefits of marriage may be biased, as most only compare married and unmarried individuals without distinguishing between those who have always been single and those who are currently single due to divorce or widowhood. Her research, as well as that of others, has found that while married individuals may be more satisfied with life than those who are divorced or widowed, there is little difference between the always single and the married, particularly when comparing those who recently got married to those who have been married for four or more years. It seems that once the initial honeymoon phase fades, married individuals are no happier or healthier than those who remain single.

Online Dating

Montenegro (2003) surveyed more than 3,000 singles aged between 40 and 69. The survey revealed that nearly half of the participants cited having someone to talk to or do things with as the most important reason for dating. Additionally, sexual fulfillment was also identified as an important goal for many. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2013) analyzed online personal ads for men and women over 40. They found that romantic activities and sexual interests were mentioned at similar rates among the middle-aged and young old age groups but less frequently for the old-old age group.

Marriage

As society evolves, more people choose different paths regarding relationships. Cohabitation, singlehood, and delayed marriage have become more common. According to the data presented in the figure, 48% of adults aged 45-54 are married, either in their first marriage (22%) or have remarried (26%). This means that marriage is still the most prevalent relationship status among middle-aged adults in the United States. Interestingly, many couples report increased marital satisfaction in midlife as their children leave home (Landsford et al., 2005). However, not all experts agree. Some suggest that those unhappy with their marriage may have already divorced by this point, which could skew reported satisfaction levels (Umberson, 2005).

Divorce

Livingston (2014) discovered that 27% of people aged 45 to 54 were divorced, with women making up 57% of divorced adults. This indicates that men are more likely to remarry than women. Women initiate two-thirds of divorces (AARP, 2009). Most divorces occur within the first 5 to 10 years of marriage, as people attempt to save their relationship but ultimately end it after limited success. Previously, divorce after 20 or more years of marriage was rare, but it has been on the rise in recent years. Brown and Lin (2012) suggest that this increase in the divorce rate among long-term marriages is due to the decreasing stigma attached to divorce and the fact that some older women are financially capable of supporting themselves after their children have grown. Additionally, with people living longer, older adults may not want to spend more years with an incompatible spouse.

Gottman and Levenson (2000) found that divorces in early adulthood were more conflictual, with each partner blaming the other for the failure of the marriage. In contrast, midlife divorces tended to be more about growing apart or cooling off of the relationship. The effects of divorce vary. Generally, young adults have a harder time adjusting to the consequences of divorce than midlife adults, with a higher risk of depression and other psychological problems (Birditt & Antonucci, 2013).

Midlife divorce is more challenging for women. According to an AARP (2009) survey, 44% of middle-aged women reported facing financial problems after their divorce, compared to only 11% of men. However, many women who divorce in midlife report that they feel a sense of release from their day-to-day unhappiness. Hetherington and Kelly (2002) found that among the enhancers and competent loners who used their divorce experience to grow emotionally and seek more productive intimate relationships or choose to stay single, the majority were women.

Dating Post-Divorce

Most divorced adults have dated by one year after filing for divorce (Anderson & Greene, 2011). One in four recent filers report having been in or were currently in a serious relationship, and over half were in a serious relationship by one year after filing for divorce. Not surprisingly, younger adults were more likely to be dating than middle-aged or older adults due to the larger pool of potential partners from which they could draw. Of course, these relationships will not all end in marriage. Teachman (2008) found that more than two-thirds of women under the age of 45 had cohabited with a partner between their first and second marriages.

Dating for adults with children can be more of a challenge. Courtships are shorter in remarriage than in first marriages. When couples are “dating,” there is less going out and more time spent in activities at home or with the children. So, the couple gets less time together to focus on their relationship. Anxiety or memories of past relationships can also get in the way. As one Talmudic scholar suggests, “When a divorced man marries a divorced woman, four go to bed” (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

Post-divorce parents gatekeep—that is, they regulate the flow of information about their new romantic partner to their children in an attempt to balance their own needs for romance with consideration regarding the needs and reactions of their children. Anderson et al. (2004) found that almost half (47%) of dating parents gradually introduce their children to their dating partner, giving both their romantic partner and children time to adjust and get to know each other. Many parents use this approach to avoid their children having to keep meeting someone new until it becomes more apparent that this relationship might be more than casual. It might also help if the adult relationship is on firmer ground to weather any initial pushback from children when it is revealed.

Grandparents

In addition to maintaining relationships with their children and aging parents, many people in middle adulthood take on another role: becoming a grandparent. The role of grandparents varies around the world. In multigenerational households, grandparents may play a more significant role in their grandchildren’s day-to-day activities. While this family dynamic is more common in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, it has increased in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2010).

Friendships

Adults of all ages who reported having a confidante or close friend with whom they could share personal feelings and concerns believed these friends contributed to a sense of belonging, security, and overall well-being (Duner & Nordstrom, 2007). Having a close friend is a factor in significantly lower odds of psychiatric morbidity including depression and anxiety (Newton et al., 2008). The availability of a close friend has also been shown to lessen the adverse effects of stress on health (Hawkley, 2008). Additionally, poor social connectedness in adulthood is associated with a more considerable risk of premature mortality than cigarette smoking, obesity, and excessive alcohol use (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010).

Female friendships and social support networks at midlife contribute significantly to a woman’s life satisfaction and well-being (Borzumato, 2009). Degges-White and Myers (2006) found that women with supportive people experience greater life satisfaction than those with a more solitary life. A friendship network or a confidant’s presence has been identified for their importance to women’s mental health (Baruch & Brooks-Gunn, 1984). Unfortunately, with numerous caretaking responsibilities at home, it may be difficult for women to find time and energy to enhance friendships that provide an increased sense of life satisfaction (Borzumato-Gainey et al., 2009). Emslie, Hunt, and Lyons (2013) found that for men in midlife, the shared consumption of alcohol was essential to creating and maintaining male friends. Drinking with friends was justified as a way for men to talk to each other, provide social support, relax, and improve mood. Although the social support provided when men drink together can be helpful, the role of alcohol in male friendships can lead to health-damaging behavior from excessive drinking.

Internet Friendships

What influence does the Internet have on friendships? It is not surprising that people use the Internet with the goal of meeting and making new friends (Fehr, 2008). Researchers have wondered if the issue of not being face-to-face reduces the authenticity of relationships or if the Internet allows people to develop deep, meaningful connections. Interestingly, research has demonstrated that virtual relationships are often as intimate as in-person relationships; in fact, Bargh and colleagues found that online relationships are sometimes more intimate (Bargh, McKenna, & Fitzsimons, 2002). This can be especially true for those individuals who are more socially anxious and lonely, as such individuals are more likely to turn to the Internet to find new and meaningful relationships. McKenna and colleagues (2002) suggest that for people who have difficulty meeting and maintaining relationships due to shyness, anxiety, or lack of face-to-face social skills, the Internet provides a safe, non-threatening place to develop and maintain relationships. Similarly, Benford and Standen (2009) found that for high-functioning autistic individuals, the Internet facilitated communication and relationship development with others, which would have been more complex in face-to-face contexts, leading to the conclusion that Internet communication could be empowering for those who feel frustrated when communicating face to face.

So, What Have You Learned?

Middle-aged adults experience various physical, cognitive, and socioemotional changes and shifts in how they perceive themselves. While individuals in their early 20s might emphasize their age to gain respect or be seen as experienced, those in their 40s tend to highlight their youthfulness. For instance, a few 40-year-olds cut each other down for being so young, stating: “You’re only 43? I’m 48!” A previous focus on the future gives way to an emphasis on the present. Neugarten (1968) notes that in midlife, people no longer think of their lives in terms of how long they have lived. Rather, life is thought of regarding how many years are left. Nonetheless, the consistency with maintaining one’s physical, cognitive, and psychosocial health during middle age allows a midlifer to embrace this current phase, resulting in successful aging.

Assignment

The section “Family Issues and Considerations” briefly discussed how the adult child(ren) is expected to care for their aging parent. In this written assignment, you will interview someone you know or seek out someone who primarily or shares responsibilities in caring for an aging parent. Inquire from them:

- What are the upsides and downsides of taking care of them?

- Any setbacks that were caused in their lives, such as careers, outside relationships, leisure time, etc.?

- How do they take care of themselves? Who is their support system?

- What advice would they like to share with others to ensure a balance between having a personal life and caring for their aging parent(s)?

Written Discussions are a more formal style of writing.

- Five pages long:

- 1 cover page

- 3 body pages

- 1 Reference list page

- Make sure to cite your source using the APA format.

- The word count has to be 300 minimum.

References

AARP. (2009). The divorce experience: A study of divorce at midlife and beyond. Washington, DC: AARP

American Association of Community Colleges. (2022). Fast Facts 2022. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/AACC_2022_Fact_Sheet.pdf

American Diabetes Association (2016). Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care, 39(1), 1-112.

Asarch, & Asarch. (2022, July 18). Is Humidity Good For Skin? – Asarch Dermatology. Asarch Dermatology. https://www.asarchcenter.com/blog/is-humidity-good-for-skin

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014a). About high blood pressure. https://www.cdc.gov/high-blood-pressure/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/about.htm

International Labour Organization. (2011). Global Employment Trends: 2011. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_150440.pdf

Marketing Charts Staff. (2014). Are young people watching less TV? http://www.marketingcharts.com/television/are-young-people-watching-less-tv-24817/

Mayo Clinic. (2014a). Heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353118

Metlife (2011). Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: Double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf

Monthly Labor Review. (2021). Percentage of the non-institutionalized civilian workforce employed by gender & age. https://www.bls.gov/cps/tables.htm#otheryears

National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015.

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick Statistics on Hearing. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing.

National Institutes of Health. (2015). Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

National Institutes of Health. (2016a) Facts about diabetes. http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/Diabetes/diabetes-facts/Pages/default.aspx

National Institutes of Health. (2007). Menopause: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000894.htm

National Sleep Foundation. (2015). 2015 Sleep in America™ poll finds pain a significant challenge when it comes to Americans’ sleep. National Sleep Foundation. https://sleepfoundation.org/ media-center/press-release/2015-sleep-america-poll

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Menopause and Insomnia. National Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/women-sleep/menopause-and-sleep

Patient Education Institute. (n.d.). Low Testosterone: MedlinePlus Interactive Health Tutorial. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000722.htm

Pew Research Center. (2010). The return of the multi-generational family household. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/03/18/the-return-of-the-multi-generational-family-household/

Pew Research Center. (2010a). How the great recession has changed life in America. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/30/how-the-great-recession-has-changed-life-in-america/