Chapter 10: Late Adulthood

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

-

- Define late adulthood.

- Compare primary and secondary aging.

- Describe theories of aging.

- Discuss theories describing psychosocial, physical, and cognitive development in late adulthood.

- Classify types of elder abuse.

Defining Late Adulthood: Age or Quality of Life?

This chapter describes typical and atypical aging processes. Late adulthood is conceptualized as anyone over the age of 65. It is important to note that some developmental psychologists separate late adulthood into four categories to describe differences within this group adequately. Those categories are 65-74, 75-84, 85-99, and 100-beyond.

Young Old – 65 to 74

The largest of the older age groups, with 33.1 million people, representing over half of the 65-and-over population (2020 Census). Having good or excellent health is reported by 41 percent of this age group (Centers for Disease Control, 2004). Their lives are more similar to those of midlife adults than those of 85 and older. This group is less likely to require long-term care, to be dependent, or to be poor and more likely to be married, working for pleasure rather than income, and living independently. About 65 percent of men and 50 percent of women between the ages of 65 and 69 continue to work full-time (He et al., 2005). The majority of the young seniors continue to live independently. Only about 3 percent of those 65-74 need help with daily living.

Old Old – 75 to 84

This age group is more likely to experience limitations on physical activity due to chronic diseases such as arthritis, heart conditions, hypertension (especially for women), and hearing or visual impairments. Death rates due to heart disease, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease are double that experienced by people 65-74. Poverty rates are 3 percent higher (12 percent) than those between 65 and 74. However, most of these 12.9 million Americans live independently or with relatives. Widowhood is more common in this group—especially among women.

Oldest Old – 85+

The number of people 85 and older is 34 times greater than in 1900 and now includes 5.7 million Americans. This group is more likely to require long-term care and to be in nursing homes. However, of the 38.9 million Americans over 65, only 1.6 million require nursing home care. Sixty-eight percent live with relatives, and 27 percent live alone (He et al., 2005; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Centenarians – 100+

There are 80,139 people over 100 years of age living in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). The majority are between ages 100 and 104, and eighty percent are women. Super-Centenarians are over 110.

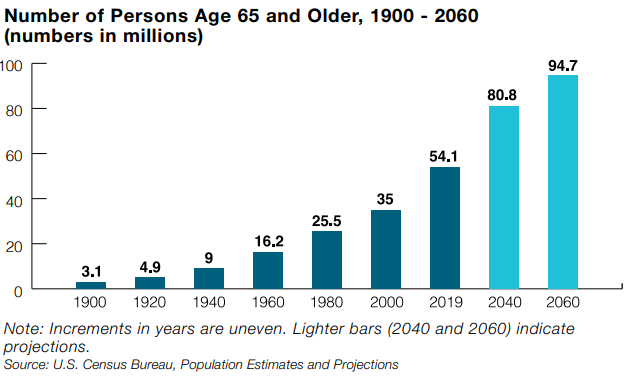

We enter late adulthood around the time that we reach our mid-sixties until death. In 2019, the U.S. population aged 65+ was 54.1 million—30 million women and 24.1 million men (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). This represents approximately 16%, or 1 in 7 population members, who are 65 or older. Since 1900, the percentage of Americans aged 65 and older nearly quadrupled (from 4.1% in 1900 to 16% in 2019), and the number increased more than 17 times (from 3.1 million to 54.1 million). The older population itself became increasingly more senior. In 2019, the 65-74 age group (31.5 million) was more than 14 times larger than in 1900 (2,186,767), the 75-84 group (16 million) was 20 times larger (771,369), and the 85+ group (6.6 million) was more than 53 times larger (122,362) (Administration on Aging, 2020). The number of people over 65 is projected to reach 94.7 million (21.6%) by 2040 due to advances in healthcare.

This chapter will highlight the continuous change, coping, and adaptation inherent in the aging process. Developmental changes vary considerably among this age group, so it is further divided into categories of 65 plus, 85 plus, and centenarians for comparison by the census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Developmentalists, however, divide this population into health and social well-being categories. Optimal aging refers to those who enjoy better health and social well-being than average. This person has no major illnesses, is still living independently, and is self-sufficient. This group is often referred to as “young old.” Normal aging refers to those with the same health and social concerns as most people. This group might need assistance with certain aspects of their lives but may function typically for their age in other areas. Much is still being done to understand precisely what normal aging means. This group is often referred to as “old old.” Impaired aging refers to those who experience poor health and dependence more than usual. This group is often referred to as “oldest old,” tends to be frail, and is often in need of care. As demonstrated here, this group is categorized by age and overall health.

At every period of life, limited resources—money, time, power—present themselves and must be adapted to. Aging successfully involves making necessary adjustments to continue living as independently and actively as possible. This is referred to as selective optimization with compensation (SOC Model) and means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive can find alternative transportation. Or a person compensating for having less energy learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion. Health professionals working with this population often help patients focus on what they can do and identify how to incorporate selective optimization with compensation best to remain independent. Promoting health and independence is essential for successful aging.

What Are the Physical Changes Associated with Late Adulthood?

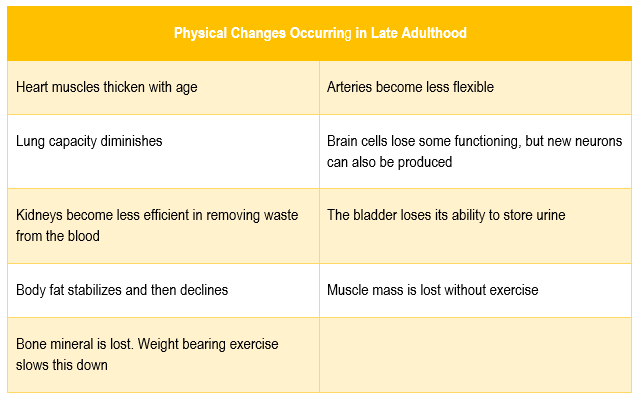

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA) (2006) traced the aging process in 1,400 people aged 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. Kidney function may deteriorate earlier in some individuals. Bone strength declines more rapidly in others. Much of this is determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. However, some generalizations about the aging process have been found.

Watch It

What Are Primary and Secondary Aging?

Changes that began in early adulthood were subtle in middle adulthood and are now noticeable in late adulthood. These changes occur in one of two ways. Primary aging, also called senescence or biological aging, is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics of the body. Primary aging refers to the inevitable changes associated with aging (Busse, 1969). These changes include changes in the skin and hair, height and weight, hearing loss, and eye disease. However, some of these changes can be reduced by limiting exposure to the sun, eating a nutritious diet, and exercising. Skin and hair change as we age. The skin becomes drier, thinner, and less elastic as we age. Scars and imperfections become more noticeable as fewer cells grow underneath the skin’s surface. Exposure to the sun, or photoaging, accelerates these changes. Graying hair is inevitable. And hair loss all over the body becomes more prevalent.

Height and weight vary with age. Older people are more than an inch shorter than they were during early adulthood (Masoro in Berger, 2005). This is thought to be due to a settling of the vertebrae and a lack of muscle strength in the back. Older people tend to weigh less than they did in midlife. Bones lose density and can become brittle. This is especially prevalent in women. However, weight training can help increase bone density after just a few weeks of training. Muscle loss occurs in late adulthood and is most noticeable in men as they lose muscle mass. Maintaining strong legs and heart muscles is vital for independence. Weightlifting, walking, swimming, or other cardiovascular exercises can help strengthen the muscles and prevent atrophy.

Many people over 65 have some difficulty with vision, but most problems can be corrected with prescriptive lenses. The most common causes of vision loss or impairment are glaucoma, cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy (He et al., 2005). Three percent of those 65 to 74 and 8 percent of those 75 and older have hearing or vision limitations that hinder activity.

Hearing loss is experienced by 30 percent of people aged 70 and older. Almost half of people over 85 have hearing loss (He et al., 2005). Older adults are more likely to seek help with vision impairment than hearing loss, perhaps due to the acceptance of eyeglasses being worn by all people and hearing aids being worn by older adults. Hearing loss causes people to withdraw from conversation and others to ignore them or shout. Shouting is usually high-pitched and challenging to understand compared to speech at lower volume. The speaker may also begin to use a condescending form of “baby talk” known as elderspeak.

Elderspeak is an inappropriate simplified speech register that sounds like baby talk and is used with older adults (Shaw & Gordon, 2021), especially in healthcare settings, that should be discouraged. Hearing loss is more prevalent in men than women.

Secondary aging refers to changes caused by illness, health habits, or disease. These illnesses are not due to increased age and may have been preventable. Typically, these illnesses derive from habits started in earlier years and maintained throughout life. However, some of these illnesses may have a genetic predisposition in conjunction with behavior. For example, hypertension or high blood pressure and associated heart disease and circulatory conditions increase with age. Hypertension usually develops over time, often from lifestyle choices related to obesity and lack of exercise. It can seriously hurt essential organs like your heart, brain, kidneys, and eyes (Whelton et al., 2017). Hypertension disables 11.1% of 65- to 74-year-olds and 17.1% of people over 75. Rates are higher among women and Blacks. Rates are highest for women over 75.

Likewise, diabetes is a disease that is an example of secondary aging. In 2008, 27% of those 65 and older had diabetes. Rates are higher among Mexican-origin individuals and Blacks than non-Hispanic Whites (National Institute on Aging, 2011). Diabetes can lead to cardiovascular disease, nerve damage, and kidney damage, increasing dependence on family members.

Osteoporosis affects 25% of women over 65 and is largely preventable with adequate calcium and protein in early life. Osteoporosis increases with age as bones become brittle and lose minerals. Bone density loss is four times more likely in women than men and becomes even more prevalent in women 85 and older. White people suffer osteoporosis more than do non-Hispanic Black people.

Secondary aging from disease, illness, or health behaviors may reduce independence, impact quality of life, affect family members and other caregivers, and bring financial burden. Aging may also be associated with disability.

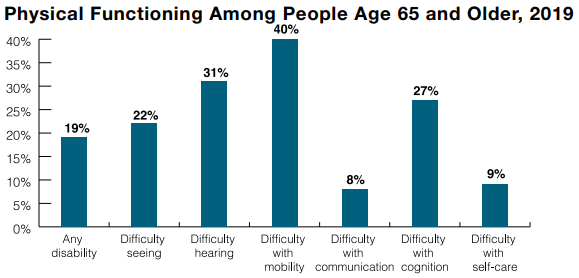

Disability and Physical Functioning: In 2019, 19% of adults aged 65 and older reported they could not function at all or had a lot of difficulty with at least one of six functioning domains. In each domain, the percentage reporting any level of difficulty varied. Specifically, 22% reported trouble seeing (even if wearing glasses), 31% reported difficulty hearing (even if wearing hearing aids), 40% said trouble with mobility (walking or climbing stairs), 8% reported difficulty with communication (understanding or being understood by others), 27% reported trouble with cognition (remembering or concentrating), and 9% reported difficulty with self-care (such as washing all over or dressing) (Administration on Aging, 2020).

What Is the Focus of Current Theories of Aging?

We must become comfortable with the idea of death. Death is inevitable. Thus, all things that are born will die. Researchers have attempted to understand the aging process, which has led to several theories of aging that involve genetics, biochemistry, animal models, and human longitudinal studies (NIA, 2011a). The significant approaches describing the aging process fall into two categories: Wear and Tear theories, which emphasize behavioral, mechanical, and environmental factors that cause damage in organisms. This damage can be a function of diet, activity, or exposure to pollutants that lead to the body simply wearing out.

-

- DNA Damage: As we live, DNA is damaged by environmental factors such as toxic agents, pollutants, and sun exposure (Dollemore, 2006). This results in deletions of genetic material and mutations in the DNA duplicated in new cells. The accumulation of these errors results in reduced functioning in cells and tissues.

- Immunosenescence: As we age, B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes become less active. These cells are crucial to our immune system as they secrete antibodies and attack infected cells. The thymus, where T-cells are manufactured, shrinks as we age. This reduces our body’s ability to fight infection (Berger, 2005). This decline in protection from the immune system can also result in increased susceptibility to diseases, autoimmune disorders, and other age-related health issues.

The other category is programmed theories, which suggest that DNA follows a pre-coded biological timetable with built-in time limits.

-

- Mitochondrial Theory of Aging: Cells divide a limited number of times and then stop. This phenomenon, known as the Hayflick limit, is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes, which divide about 50 times before becoming senescent. Senescent cells do not die. They stop replicating. Senescent cells can help limit the growth of other cells, which may reduce the risk of developing tumors when younger, but can alter genes later in life and promote the growth of tumors as we age (Dollemore, 2006). Limited cell growth is attributed to telomeres, the tips of the protective coating around chromosomes. Each time cells replicate, the telomere is shortened. Eventually, loss of telomere length is thought to damage chromosomes and produce cell senescence. Over time, mitochondrial DNA damage and decline in function can lead to decreased energy production and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cells.

- Free Radical Theory: As we metabolize oxygen, mitochondria in the cells convert oxygen to adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which provides energy to the cell. Unpaired electrons are a byproduct of this process, and these unstable electrons cause cellular damage as they find other electrons with which to bond. These free radicals have some benefits and are used by the immune system to destroy bacteria. However, cellular damage accumulates and eventually reduces the functioning of organs and systems. Many food products and vitamin supplements are promoted as age-reducing, but the ability to slow aging by introducing antioxidants in the diet is still controversial.

- Crosslinking/Glycation Theory: This theory focuses on the role blood sugar, or glucose, plays in the aging of cells. Glucose molecules attach themselves to proteins and form chains or crosslinks. These crosslinks reduce the flexibility of the tissue, and the tissue becomes stiff and loses function. The circulatory system becomes less efficient as the heart, arteries, and lung tissue lose flexibility. And joints grow stiff as glucose combines with collagen. (To demonstrate this process, take a piece of meat and place it in a hot skillet. The outer surface of the meat will caramelize, and the tissue will become stiff and rigid.)

It is important to note that aging is a complex and multifaceted process, likely involving a combination of these and other factors. Despite a wealth of studies on the genetics of aging, we still have a poor understanding of how common mutations with age-specific effects are (Brengdahl et al., 2022)

What Are the Health Issues Typically Associated with Late Adulthood?

Several health issues are commonly associated with old age due to the physiological changes and accumulation of risk factors over time. However, it is possible to be diagnosed with either of these diseases at any age. Remember that individual experiences can vary widely, and not everyone will develop all of these conditions.

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe the loss of cognitive functioning—thinking, remembering, and reasoning—to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily life and activities (NIA, 2022). The following chart contains the names and a brief description of the most common types of dementia.

Types of Dementia |

Brief Description |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Most common dementia diagnosis among older adults. It is caused by changes in the brain, including abnormal buildups of proteins known as amyloid plaques and tau tangles. |

| Frontotemporal dementia | It is a rare form of dementia that tends to occur in people younger than 60. It is associated with abnormal amounts or forms of the proteins tau and TDP-43. |

| Lewy body dementia | A form of dementia caused by abnormal deposits of the protein alpha-synuclein, called Lewy bodies. |

| Vascular dementia | A form of dementia caused by conditions that damage blood vessels in the brain or interrupt the flow of blood and oxygen to the brain.

Mixed dementia is a combination of two or more types of dementia. For example, through autopsy studies involving older adults who had dementia, researchers have identified that many people had a combination of brain changes associated with different forms of dementia. |

Note: Click on the name of each type of dementia to access more information on the NIA website.

Parkinson’s Disease: A neurodegenerative disorder that can cause tremors, rigidity, and difficulty with balance and movement. Parkinson’s disease symptoms can differ for everyone. Still, typical symptoms may include tremors, slowed movement, bradykinesia, rigid muscles, impaired posture and balance, loss of automatic movements, and speech changes.

Osteoarthritis: This is the leading cause of disability in older adults. Arthritis results in swelling of the joints and connective tissue that limits mobility. Arthritis is more common among women than men and increases with age. About 19.3 percent of people over 75 are disabled with arthritis; 11.4 percent of people between 65 and 74 experience this disability.

Cancer: In 2020, in the United States, 1,603,844 new cancer cases were reported, and 602,347 people died of cancer. For every 100,000 people, 403 new cancer cases were reported, and 144 died of cancer (CDC/Cancer Statistics, 2023). Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, exceeded only by heart disease. One of every five deaths in the United States is due to cancer. The risk of various types of cancer, such as breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancer, increases with age. Most people who are diagnosed with cancer and most cancer survivors are older than 65 (Cancer.net, 2023). 60% of newly diagnosed malignant tumors and 70% of cancer deaths occur in people 65 or older. Men over 75 have the highest rates of cancer at 28 percent. Women 65 and older have rates of 17 percent (Lang et al.).

Is There a Relationship between Wellness and Illness in Late Adulthood?

The relationship between wellness and illness in late adulthood is complex and multifaceted and should be approached from a biopsychosocial perspective. Late adulthood is a life stage characterized by significant physical, psychological, and social changes. The balance between wellness and illness in this stage can vary significantly among individuals due to genetics, lifestyle, social support, and access to healthcare. Ultimately, the relationship between wellness and illness in late adulthood emphasizes the importance of proactive health management.

The interplay between wellness and illness in late adulthood can be best highlighted by being mindful of the following:

- Preventive Measures: Healthy lifestyle choices, such as staying active, eating well, and managing stress, can help prevent or delay the onset of certain illnesses and maintain overall wellness.

- Adaptation: Many older adults exhibit resilience and adaptability in the face of health challenges. They learn to manage their conditions, make necessary lifestyle adjustments, and seek support when needed.

- Quality of Life: The balance between wellness and illness dramatically influences an individual’s quality of life in late adulthood. Effective management of health issues and focusing on wellness can contribute to a higher quality of life.

What Are the Cognitive Changes Associated with Late Adulthood?

The Sensory Register

Aging may create small decrements in the sensitivity of the sensory register. And, to the extent that a person has a more difficult time hearing or seeing, that information will not be stored in memory. This is an important point because many older people assume that if they cannot remember something, it is because their memory is poor. It may be that the information was never seen or heard.

The Working Memory

Older people have more difficulty using memory strategies to recall details (Berk, 2007). As we age, the working memory loses some of its capacity. Concentrating on more than one thing at a time makes it more challenging to remember an event’s details. However, people compensate for this by writing down information and avoiding situations where there is too much going on at once to focus on a particular cognitive task (Herkimer, n.d.).

The Long-Term Memory

This type of memory involves the storage of information for long periods. Retrieving such information depends on how well it was learned in the first place rather than how long it has been stored. If information is stored effectively, an older person may remember facts, events, names, and other information stored in long-term memory throughout life. Adults of all ages seem to have similar memories when asked to recall the names of teachers or classmates. And older adults remember more about their early adulthood and adolescence than middle adulthood (Berk, 2007). Older adults retain semantic memory or the ability to remember vocabulary.

Younger adults rely more on mental rehearsal strategies to store and retrieve information. Older adults focus more on external cues such as familiarity and context to recall information (Berk, 2007). And they are more likely to report the main idea of a story rather than all the details (Jepson & Labouvie-Vief, in Berk, 2007).

A positive attitude about being able to learn and remember plays a vital role in memory. When people are stressed (perhaps feeling worried about memory loss), they have more difficulty taking in information because they are preoccupied with anxieties. Many laboratory memory tests require comparing the performance of older and younger adults on timed memory tests in which older adults do not perform as well. However, few real-life situations require speedy responses to memory tasks. Older adults rely on more meaningful cues to remember facts and events without impairing everyday living.

Wisdom

Wisdom is the ability to use common sense and good judgment. A wise person is insightful and has knowledge that can be used to overcome obstacles in living. Does aging bring wisdom? While living longer brings experience, it does not always bring wisdom. Those who have had experience helping others resolve problems in living and those who have served in leadership positions seem to have more wisdom. So age combined with a specific type of experience brings wisdom. However, older adults have greater emotional wisdom or the ability to empathize with and understand others.

Problem-Solving

Problem-solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly (a kind of task that might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes) decline with age. However, real-life challenges facing older adults do not rely on the processing speed or making choices independently. Older adults can resolve everyday problems by depending on input from others, such as family and friends. They are less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on crucial medical care (Strough et al., 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

What Are the Theories Describing Psychosocial Development in Late Adulthood?

As more people age, we must consider what that means. No longer are 60-year-olds sitting at home engaging in stereotypical activities ascribed to older adults. Erik Erikson proposed a theory describing the psychosocial process of aging in late adulthood. Integrity versus despair is the eighth stage in Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. This stage occurs in late adulthood, usually around age 65 and beyond. It represents the psychological conflict that individuals confront as they reflect on their lives and the meaning of their experiences. Erikson (1980) believed that late adulthood is a time for making sense of one’s life, finding meaning to one’s existence, and adjusting to inevitable death. Erikson proposes that during this time, one reviews one’s life and finds self-acceptance or is discontent with how one’s life was. People can make an effort to reconnect with others and rebuild fractured relationships. If they cannot rebuild those relationships, they may still find peace knowing they tried. Bitterness and resentment lead to despair when one cannot make peace with life choices.

Joan Erikson, Erik Erikson’s wife, extended the psychosocial theory to include a ninth stage that describes how people who reach elderhood and are in good health often have a shift in mindset, which allows for a reinterpretation of life. She suggests that older adults revisit the previous eight stages and deal with the earlier conflicts in new ways. In the first eight stages, conflicts are presented in a syntonic-dystonic matter, meaning that the first term listed in the conflict is the positive, sought-after achievement, and the second term is the less-desirable goal (i.e., trust is more desirable than mistrust and integrity is more desirable than despair) (Perry et al., 2015). However, in the ninth stage, people are less concerned with this duality and make progress towards gerotranscendence.

Gerotranscendence is a concept introduced by Swedish gerontologist Lars Tornstam (2005) that represents a perspective on aging and the psychological development that can occur in late adulthood. Gerotranscendence suggests that as individuals grow older, their understanding of life and the world may transform, leading to a shift in priorities, values, and perceptions. The critical characteristics of gerotranscendence include (1) increased transcendence, (2) a shift in cosmic and spiritual perspective, (3) decreased interest in materialism, (4) desire for solitude, (5) greater emotional complexity, and (6) reevaluation of relationships. Gerotranscendence challenges the stereotypical view of aging as a time of decline and disengagement. Instead, it suggests that aging can bring about personal growth, wisdom, and a deeper connection to the mysteries of life.

Activity Theory

Developed by gerontologist Robert James Havighurst in 1961, activity theory proposes that older adults are happiest when they stay active and maintain social interactions. Often, older people are barred from meaningful activities as they age (Nilsson et al., 2015). These activities, especially when meaningful, help the elderly to replace lost life roles after retirement and, therefore, resist the social pressures that limit an older person’s world. The central principle of this theory asserts that social integration is necessary for people to derive a sense of purpose, identity, and satisfaction as they adjust to the changing circumstances of old age—e.g., retirement, illness, loss of friends and loved ones through death, etc. Activity theory thus strongly supports avoiding a sedentary lifestyle and considers it essential to health and happiness that the older person remains active physically and socially.

Further, activity theory acknowledges that as people age, they may face physical or cognitive limitations that can affect their ability to engage in certain activities. In response to these limitations, individuals may compensate by finding alternative activities that suit their skills and interests. In other words, the more active older adults are, the more stable and positive their self-concept will be, leading to greater life satisfaction and higher morale (Havighurst & Albrecht, 1953).

Productivity at Work

Some continue to be productive at work. Mandatory retirement is now illegal in the United States. However, many people choose retirement by age 65, and most leave work by choice. Those who do leave by choice adjust to retirement more easily. Chances are, they have prepared for a smoother transition by gradually giving more attention to a hobby or interest as they approach retirement. And they are more likely to be financially ready to retire. Those who must leave abruptly for health reasons or because of layoffs or downsizing have more difficulty adjusting to their new circumstances. Men, especially, can find unexpected retirement difficult. Women may feel less of an identity loss after retirement because much of their identity may have also come from family roles. But women tend to have poorer retirement funds accumulated from work, and if they take their retirement funds in a lump sum (be that from their own or a deceased husband’s funds), they are more at risk of outliving those funds. Women need better financial retirement planning.

By 2030, all baby boomers will be at least 65, and 9.5 percent of the civilian labor force is projected to be older than 65. The share of older people in the labor force is growing, and their labor force participation rates are rising.

The labor force participation rate for people aged 16 and older will decline from 61.7 percent in 2020 to 60.4 percent in 2030. The labor force participation rate for people ages 16 to 24 will decrease from 53.9 percent in 2020 to 49.6 percent in 2030. The rate for people aged 25 to 54 is projected to hold steady, while the rate for people aged 55 to 74 is projected to decrease slightly. The only age group whose labor force participation rate is projected to rise is people aged 75 and older, from 8.9 percent in 2020 to 11.7 percent by 2030 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021).

Education

Twenty percent of people over 65 have a bachelor’s or higher degree. And over 7 million people over 65 take adult education courses (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Lifelong learning through continuing education programs on college campuses or “Elderhostels,” which allow older adults to travel abroad, live on campus, and study, provides enriching experiences. Academic courses and practical skills such as computer classes, foreign languages, budgeting, and holistic medicines are among the courses offered. Older adults with higher education levels are more likely to take continuing education. However, offering more educational experiences to a diverse group of older adults, including those institutionalized in nursing homes, can enhance the quality of life.

Volunteering: Face-to-face and Virtually

About 40 percent of older adults are involved in some structured, face-to-face volunteer work. Many older adults, about 60 percent, engage in a sort of informal type of volunteerism, helping neighbors or friends rather than working in an organization (Berger, 2005). They may help a friend by taking them somewhere, shopping for them, etc. Some do participate in organized volunteer programs, but those who do tend to work part-time. Those who retire and do not work are less likely to feel that they have a contribution to make. (It’s as if when one gets used to staying at home, their confidence to go out into the world diminishes.) And those who have recently retired are more likely to volunteer than those over 75 years of age.

New opportunities exist for older adults to serve as virtual volunteers by dialoguing online with others worldwide and sharing their support, interests, and expertise. According to an article from AARP (American Association of Retired Persons), virtual volunteerism has increased from 3,000 in 1998 to over 40,000 participants in 2005. These volunteer opportunities range from helping teens with their writing to communicating with “neighbors” in villages of developing countries. Virtual volunteering is available to those who cannot engage in face-to-face interactions and opens up a new world of possibilities and ways to connect, maintain identity, and be productive (Uscher, 2006).

Religious Activities

People also become more involved in prayer and religious activities as they age. This provides a social network and a belief system that combats the fear of death. It provides a focus for volunteerism and other activities as well. For example, one older woman prides herself on knitting prayer shawls given to sick people. Another serves on the altar guild and is responsible for keeping robes and linens clean and ready for communion.

Political Activism

Older adults are very politically active. They have high voting rates and write letters to Congress on issues that affect them and a wide range of domestic and foreign concerns. In the 2008 election, 70 percent of people 65 and older voted. This group is tied with 45–65-year-olds having the highest voter turnout (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

What Do the Lives of the Aging Population Look Like?

Grandparenting

Grandparenting typically begins in midlife rather than late adulthood, but because people live longer, they can anticipate being grandparents for extended periods. Cherlin and Furstenberg (1986) describe three styles of grandparents:

- Remote: These grandparents rarely see their grandchildren. Usually, they live far away from their grandchildren but may also have a distant relationship. Contact is typically made on special occasions such as holidays or birthdays. Thirty percent of the grandparents studied by Cherlin and Furstenberg were remote.

- Companionate Grandparents: Fifty-five percent of grandparents studied were described as “companionate.” These grandparents do things with their grandchildren but have little authority or control. They prefer to spend time with them without interfering in parenting. They are more like friends to their grandchildren.

- Involved Grandparents: Fifteen percent of grandparents were described as “involved.” These grandparents take a very active role in their grandchild’s life. Their children might even live with their grandparents. The involved grandparent has frequent contact with and authority over the grandchild.

An increasing number of grandparents are raising grandchildren today. Issues such as custody, visitation, and continued contact between grandparents and grandchildren after parental divorce are contemporary concerns.

Marriage and Divorce

Fifty-six percent of people over 65 are married (He et al., 2005). 91% of men and 92% of women aged 60 to 69 and 95% of men and women aged 70 or older have been married (Gurrentz & Mayol-Garcia, 2021). Many married couples feel their marriage has improved with time, and the emotional intensity and level of conflict that might have been experienced earlier has declined. This is not to say that bad marriages become good over the years, but that those very conflict-ridden marriages may no longer be together and that many of the disagreements couples might have had earlier in their marriages may no longer be concerns. Children have grown, and the division of labor in the home has probably been established. Men tend to report being more satisfied with marriage than women. Women are more likely to complain about caring for an ill spouse, accommodating a retired husband, and planning activities. Older couples continue to engage in sexual activity, but with less focus on intercourse and more on cuddling, caressing, and oral sex (Carroll, 2007).

Divorce after a long-term marriage does occur, but it is not very common. While 34% of women and 33% of men ages 20 or older who ever married had ever divorced, the percentage of adults 55 to 64 years who divorced is much higher: about 43% for both sexes. Although significantly lower compared to 55- to 64-year-olds, high divorce rates persist for those 65 to 74 years at 39%, which is still higher than for the general adult population. For adults aged 75 or older, the rate is lower at 24% (Gurrentz & Mayol-Garcia, 2021). A longer life expectancy and the expectation of happiness cause some older couples to begin a new life after divorce after 65. Consider Betty, who divorced after 40 years of marriage. Her marriage had never been ideal, but she stuck with it, hoping things would improve because she didn’t want to hurt her husband’s reputation (he was in a job where divorce was frowned upon). But she always hoped for more freedom and happiness in life, and once her family obligations were no longer as outstanding (the children and grandchildren were on their own), she and her husband divorced. She characterized this as an act of love in that she and her ex-husband could pursue their dreams later in life (Author’s notes). Older adults who have been divorced since midlife tend to have settled into comfortable lives and, if they have raised children, to be proud of their accomplishments as single parents.

Widowhood

Twenty-nine percent of people over 65 are widowed (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). The death of a spouse is one of life’s most disruptive experiences. It is tough on men who lose their wives. Often, widowers do not have a network of friends or family members to fall back on and may have difficulty expressing their emotions to facilitate grief. Also, they may have depended on their mates for routine tasks such as cooking, cleaning, etc. In addition, they typically expect to precede their wives in death and, by losing a wife, must adjust to something unexpected. However, if a man can adapt, he will find that he is in great demand should he decide to remarry.

Widows may have less difficulty because they have a social network and can handle their daily needs. They may have more financial difficulty if their husbands have previously taken all the finances. They are much less likely to remarry because many do not wish to, and fewer men are available. At 65, there are 73 men for every 100 women. The sex ratio becomes even further imbalanced at 85, with 48 men to every 100 women (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Loneliness or solitude? Loneliness is a discrepancy between the social contact a person has and the contacts a person wants (Brehm et al., 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness due to social isolation, and men from emotional isolation. A lack of self-worth, impatience, desperation, and depression can accompany loneliness. This can lead to suicide, particularly in older White men with the highest suicide rates of any age group, more elevated than Blacks and higher than females. Rates of suicide continue to climb and peak in males after age 85 (National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, 2002).

Single, Cohabiting, and Remarried Older Adults

About 4 percent of adults never marry. Many have long-term relationships, however. The never-married tend to be very involved in family and caregiving and do not appear to be particularly unhappy during late adulthood, especially if they have a healthy network of friends. Friendships tend to be a significant influence on life satisfaction during late adulthood. Friends may be more influential than family members for many older adults. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults become more selective in their friendships than when they were younger (Carstensen, Fung, & Charles, 2003). Friendships are not formed to enhance status or careers and may be based purely on a sense of connection or the enjoyment of being together. Most older adults have at least one close friend. These friends may provide emotional as well as physical support. Talking with friends and relying on others is very important during this stage of life.

About 4 percent of older couples chose cohabitation over marriage (Chevan, 1996). As discussed in our lesson on early adulthood, these couples may prefer cohabitation for financial reasons, be same-sex couples who cannot legally marry, or do not want to marry because of previous dissatisfaction with marital relationships. There are between 1 and 3 million gay and lesbian older adults in America today, and numbers will continue to increase (Cahill et al., 2000). These older adults have concerns over health insurance and being able to share living quarters in nursing homes and assisted living residences where staff members tend not to accept homosexuality and bisexuality. Senior Action in a Gay Environment (SAGE) is an advocacy group working on remedying these concerns. Same-sex couples who have endured prejudice and discrimination through the years and can rely upon one another continue to have support through late adulthood. Those who are institutionalized, however, may find it harder to live together.

Couples who remarry after midlife tend to be happier in their marriages than in their first marriage. These partners will likely be more financially independent, have grown children, and enjoy greater emotional wisdom from experience.

Residence

Older adults do not typically relocate far from their previous places of residence during late adulthood. A minority lives in planned retirement communities that require residents to be of a certain age. However, many older adults live in age-segregated neighborhoods that have become segregated as original inhabitants have aged and children have moved on. A primary concern in future city planning and development will be whether older adults wish to live in age-integrated or age-segregated communities.

Older Adults, Caregiving, and Long-Term Care

We previously noted the number of older adults who require long-term care and said that the number increases with age. Most (70 percent) of older adults who need care receive that care in the home. Most are cared for by their spouse or by a daughter or daughter-in-law. However, those who are not cared for at home are institutionalized. In 2008, 1.6 million out of the total 38.9 million Americans age 65 and older were nursing home residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Among 65-74, 11 per 1,000 adults aged 65 and older were in nursing homes. That number increases to 182 per 1,000 after age 85. More residents are women than men, and more are Black than White. As the population of those over 85 continues to increase, more will require nursing home care. Meeting nursing home residents’ psychological, social, and physical needs is a growing concern. Rather than focusing primarily on food, hygiene, and medication, quality of life within these facilities is essential. Residents of nursing homes are sometimes stripped of their identity as their possessions and reminders of their lives are taken away. A rigid routine in which the residents have little voice can be alienating to an older adult. Routines that encourage passivity and dependence can damage self-esteem and lead to further deterioration of health. Greater attention needs to be given to promoting successful aging within institutions.

What Is Elder Abuse?

Elder abuse is an intentional act or failure to act that causes or creates a risk of harm to an older adult (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2021). Elder abuse is common and is experienced by about 1 in 10 people aged 60 and older who live at home. From 2002 to 2016, more than 643,000 older adults were treated in the emergency department for nonfatal assaults, and over 19,000 homicides occurred. It is believed that these statistics are an underestimate because many cases of elder abuse go unreported due to factors such as fear, shame, or dependence on the abuser. The abuse occurs at the hands of a caregiver or someone the elder trusts. Common types of elder abuse include neglect, physical, and emotional/psychological.

Nursing homes have been publicized as places where older adults are at risk of abuse. Abuse and neglect of nursing home residents are often found in facilities run down and understaffed. However, older adults are more frequently abused by family members. The most reported types of abuse are financial abuse and neglect. Victims are usually very frail and impaired, and perpetrators depend on the victims for support. Prosecuting a family member who has financially abused a parent is very difficult. The victim may be reluctant to press charges, and the court dockets are often very full, resulting in long waits before a case is heard. Granny dumping, or family members abandoning older families with severe disabilities in emergency rooms, is a growing problem. An estimated 100,000 and 200,000 are dumped yearly (Tanne in Berk, 2007).

References

Administration on Aging is part of the Administration for Community Living for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2020ProfileOlderAmericans.Final_.pdf#:~:text=In%20the%20U.S.%20the%20population%20age%2065%20and,population%2C%20more%20than%20one%20in%20every%20seven%20Americans.

Brengdahl, M. I., Kimber, C. M., Shenoi, V. N., Dumea, M., Mital, A., & Friberg, U. (2022). Age-specific effects of deletions: implications for aging theories. Evolution, 77(1), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/evolut/qpac027

Busse, E. W. (1969). Theories of aging. In E. W. Busse & E. Pfeiffer (Eds.), Behavior and adaptation in late life. (pp. 11-31).

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the lifespan(6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the lifespan(4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, The Economics Daily, Number of people 75 and older in the labor force is expected to grow 96.5 percent by 2030 at https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/number-of-people-75-and-older-in-the-labor-force-is-expected-to-grow-96-5-percent-by-2030.htm (visited September 01, 2023).

Cancer and Aging. (2023) Cancer. Net. Retrieved 8/28/2023 from https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/adults-65/cancer-and-aging

Carroll, J. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Carstenson, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and emotion regulation in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 103-123.

Chevan, A. (1996). As cheaply as one: Cohabitation in the older population. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 656-667.

Dollemore, D. (2006, August 29). “Aging Under the Microscope,” Publications. National Institute on Aging.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton.

Gurrentz, B & Mayol-Garcia, Y. (2021). Marriage, Divorce, and Widowhood Remain Prevalent Among Older Populations. Retrieved 9/1/2023 from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/love-and-loss-among-older-adults.html#:~:text=Although%20significantly%20lower%20when%20compared,rate%20is%20lower%20at%2024%25.

Havighurst, R. J., & Albrecht, R. (1953). Older people.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (n.d.). U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P23-209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U.S. Census Bureau).

Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem-solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(1), 6-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283

National Institute on Aging. (2011a). Biology of aging: Research today for a healthier tomorrow. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/budget/biology-aging-3

National Institute on Aging, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Home Page. (n.d.). National Institute on Aging – Intramural Research Program.

NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA). (2022). Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias. Retrieved 8/28/2023 from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-is-dementia

Perry, T. E., Ruggiano, N., Shtompel, N., & Hassevoort, L. (2015). Applying Erikson’s wisdom to self-management practices of older adults: findings from two field studies. Research on Aging, 37(3), 253–274. doi:10.1177/0164027514527974

Shaw, C. A., Gordon, J. K. Understanding Elderspeak: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Innov Aging. 2021 Jul 3;5(3):igab023. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab023. PMID: 34476301; PMCID: PMC8406004.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248.

Tornstam L. (2005). Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. Springer. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=gnh&AN=110902&site=ehost-live.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999–2020): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz, released in June 2023.

United States Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html

United States, National Center for Health Statistics. (2022). National Vital Statistics Report, 50(16). Retrieved May 7, 2011, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK1_2000.pdf

United States, National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). Alzheimer’s Disease, Education, and Referral Center. Update January 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2011, from http://www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers/Publications/ADProgress2009/Introduction

Uscher, J. (2006, January). How to make a world of difference without leaving home. AARP The Magazine – Feel Great. Save Money. Have Fun. Retrieved May 07, 2011, from http://www.aarpmagazine.org/lifestyle/virtual_volunteering.html

The author of this chapter, Cynthia Thomas, Ph.D., contributed the following changes to this chapter:

- Revised and updated Defining Late Adulthood. Included current information, including the graphic on the 65 and older population.

- Revised and updated the section “What are the physical changes associated with late adulthood?” Added a chart to organize the information and the link to The National Institute on Aging’s Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, America’s longest-running scientific study of human aging.

- Rewrote the section entitled “What is primary and secondary aging?” Included additional research from current sources. Extended the section on secondary aging and highlighted the type and rate of disability in people older than 65 years.

- Extended the discussion on the different theories of aging. Focused on the primary theories from two theoretical categories—Programmed theories and Wear and Tear theories. Incorporated a section called “What are the health issues typically associated with late adulthood?”

- Discussed different types of dementia and included a link to a website for further description of each. Introduced discussions about Parkinson’s Disease, Osteoarthritis, and cancer. Provided a link to a video that discusses cancer care for older adults.

- Extended the discussion on psychosocial development in late adulthood and included a discussion on gerotranscendence. Highlighted healthy aging through the discussion of activity theory, productivity at work, education, and other activities that active elders engage.

- Added a discussion and activity about different types of elder abuse.

Media Attributions

- 5905707327_e64294f425_k © Shreveport-Bossier Convention and Tourist Bureau is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ch10_Number of People 65plus © U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates and Predictions is licensed under a Public Domain license

- kareem_80yo bodybuilder © Adam Cohn is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Physical Changes in late adulthood © Cynthia Thomas is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ch10 – Physical Functioning among 65 plus © Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Civilian Labor Force chart © Bureau of Labor Statistics is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license