Chapter 1: Introduction to Lifespan Development

Learning Objectives:

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the study of human development

- Define physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development

- Differentiate periods of human development

- Analyze your location in the lifespan

- Critique stage theory models of human development

- Define culture and ethnocentrism and describe ways that culture impacts development

Welcome to Lifespan Development; this is how and why people change or remain the same over time, which can also be referred to as human development.

Think about how you were five, ten, or even fifteen years ago. How have you changed? How have you remained the same?

In this textbook, we will look at how:

- We change physically from early development through aging and death.

- Our cognitive changes, or the ability to think and remember.

- Our concerns and psychological state are influenced by age.

- Our social relationships change throughout life.

New Assumptions, Understandings, and Expectations

Our journeys through life are more than biological; they are shaped by cultural, historical, economic, and political realities as much as they are influenced by physical change. One of the best ways to gain perspective on our own lives is to compare our experiences with those of others. This text hopes to give you many eyes to see your development by periodically making cross-cultural and historical comparisons and presenting various views on healthcare, aging, education, gender, and family roles.

Today, we are more aware of the variations in development and the impact that culture and the environment have on shaping our lives. We no longer assume that those who develop in predictable ways are normal and those who do not are abnormal. The assumption that early childhood experiences dictate our future is also being questioned. Instead, we have come to appreciate that growth and change are steady throughout life, and experience continues to impact who we are and how we relate to others. We recognize that adulthood is a dynamic period of life marked by continued cognitive, social, and psychological development.

This text hopes to recreate a rich experience where students from various cultural backgrounds discuss their interpretations of developmental tasks and concerns as much as possible. Another highlight of the text is that you will notice the discussions of various developmental factors that target Louisianans. What a great way for native students to discover how their Louisiana culture influences their development.

C’est parti! or “Let’s Begin!”

Culture

Culture is often referred to as a blueprint or guideline shared by a group that specifies how to live. It includes ideas about right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, and what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations.

Culture is learned from parents, schools, churches, media, friends, and others throughout life. The traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture help members function and value their society. We tend to believe that our culture’s practices and expectations are exemplary. (This belief that our own culture is superior is called ethnocentrism and is a normal by-product of growing up in a culture. It becomes a roadblock, however, when it inhibits understanding of cultural practices from other societies.) Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that particular culture.

Culture is an essential context for human development, and understanding development requires identifying which development features are culturally based. This understanding is somewhat new and still being explored. So much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and difficult to apply to various cultural contexts. The reader should remember this and realize that much is still unknown when comparing development across cultures.

For example:

Erikson’s assumption that teenagers struggle with identity assumes that all teenagers live in a society with many options and must make individual choices about their future. In many parts of the world, one’s identity is determined by family status or society’s dictates. In other words, there is no choice.

Exercise

Think of other ways culture may have affected your development. How might cultural differences influence interactions between teachers and students, nurses and patients, or other relationships?

Periods of Development

Developmentalism breaks the lifespan into nine stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development

- Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Early Childhood

- Middle Childhood

- Adolescence

- Emerging and Early Adulthood

- Middle Adulthood

- Late Adulthood

- Death and Dying

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adulthood that will be explored in this book. So, while an 8-month-old and an 8-year-old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs differ, and their primary psychological concerns are distinctive. The same is true of an 18-year-old and an 80-year-old, both considered adults.

Here is a brief overview of the stages:

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs, and development begins. All of the significant structures of the body are forming, and the mother’s health is vitally important. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to congenital disabilities), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The first year and a half to two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change known as infancy and toddlerhood. A newborn with a keen sense of hearing but impoverished vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short time. Caregivers are also converted from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also called the preschool years that follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three-to-five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and learning the workings of the physical world. However, this knowledge does not come quickly, and preschoolers may have initially had interesting conceptions of size, time, space, and distance, such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others.

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood, and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now, the world has become one of learning and testing new academic skills and assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by comparing oneself and others. Growth rates slow down, and children can refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences.

Emerging and Early Adulthood

The twenties and thirties are often thought of as early or emerging adulthood. It is a time when we are at our physiological peak but are most at risk for involvement in violent crimes and substance abuse. It is a time of focusing on the future and putting a lot of energy into making choices that will help one earn the status of a full adult in the eyes of others. Love and work are primary concerns at this stage of life.

Middle Adulthood

The late thirties through the mid-sixties is referred to as middle adulthood. This is a period in which aging, which began earlier, becomes more noticeable and a period at which many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work. It may be a period of gaining expertise in specific fields, understanding problems, and finding solutions more efficiently than before. It can also be a time of becoming more realistic about previously considered possibilities and recognizing the difference between what is possible and what is likely.

Late Adulthood

This lifespan has increased in the last 100 years, particularly in industrialized countries. Late adulthood is sometimes subdivided into two or three categories, such as the “young old” and “old old” or the “young old,” “old old,” and “oldest old.” We will follow the former categorization and distinguish between the “young old” people between 65 and 79 and the “old old” or those who are 80 and older.

One of the primary differences between these groups is that the “young old” are very similar to midlife adults: still working, still relatively healthy, and still interested in being productive and active. The “old old” remain energetic, and most continue living independently. Still, risks of diseases associated with aging, such as arteriosclerosis, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease, increase substantially for this age group. Housing, healthcare, and extending active life expectancy are only a few topics of concern for this age group.

A better way to appreciate the diversity of people in late adulthood is to go beyond chronological age and examine whether a person is experiencing optimal aging (excellent health and continues to have an active, stimulating life), normal aging (in which the changes are similar to most of those of the same age), or impaired aging (referring to someone who has more physical challenge and disease than others of the same age group).

Death and Dying

This topic is seldom given the amount of coverage it deserves. Of course, there is a certain discomfort in thinking about death, but there is also a certain confidence and acceptance that can come from studying death and dying. We will be examining the physical, psychological, and social aspects of death, exploring grief or bereavement, and addressing ways in which helping professionals work in death and dying. We will discuss cultural variations in mourning, burial, and grief.

References

Steinberg, L. (2013). Adolescence (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. ↵

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908.

Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54.

Bleil, M. E., Booth-LaForce, C., & Benner, A. D. (2017). Race disparities in pubertal timing: Implications for cardiovascular disease risk among African American women. Population research and policy review, 36(5), 717–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-017-9441-5.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley

Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 225–241.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York, NY: Norton.

Freeman, H.; Magee, B.; Ortis, G.; Lebrun, A. (2023, June 26). Growing Up as an Adolescent in Louisiana—Developmental Psychology. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OXXvEVl6Yak.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford.

Hartley, C. A. & Somerville, L. H. (2015). The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 5, 108-115.

Kim, E. (2016, June 20). James Marcia’s Adolescent Identity Development. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/-JrZwmHU9xE

Levine, L. E. & Munsch, J. (2015). Child Development from Infancy to Adolescence. Retrieved from https://edge.sagepub.com/levinechrono on June 5, 2023.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1341–1353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020205.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life course persistent antisocial behavior: Developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press.

Phinney, J. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34–49.

Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372–1384.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085

Steinberg, L. (2013). Adolescence (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

The University of North Carolina and Chapel (2023). Study Shows Habitual Checking of Social Media May Impact Young Adolescents’ Brain Development. Retrieved from https://www.unc.edu/posts/2023/01/03/study-shows-habitual-checking-of-social-media-may-impact-young-adolescents-brain-development/#:~:text=The%20study%20findings%20suggest%20that,more%20sensitive%20to%20social%20feedback on June 5, 2023.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Attribution

This chapter was adapted by Tremika Cleary from select chapters in Iowa State University Digital Press Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being, authored by Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Tera Jones; and Lumen Learning, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Family reunion – TC- ch1 © Tremika Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- prenatal is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

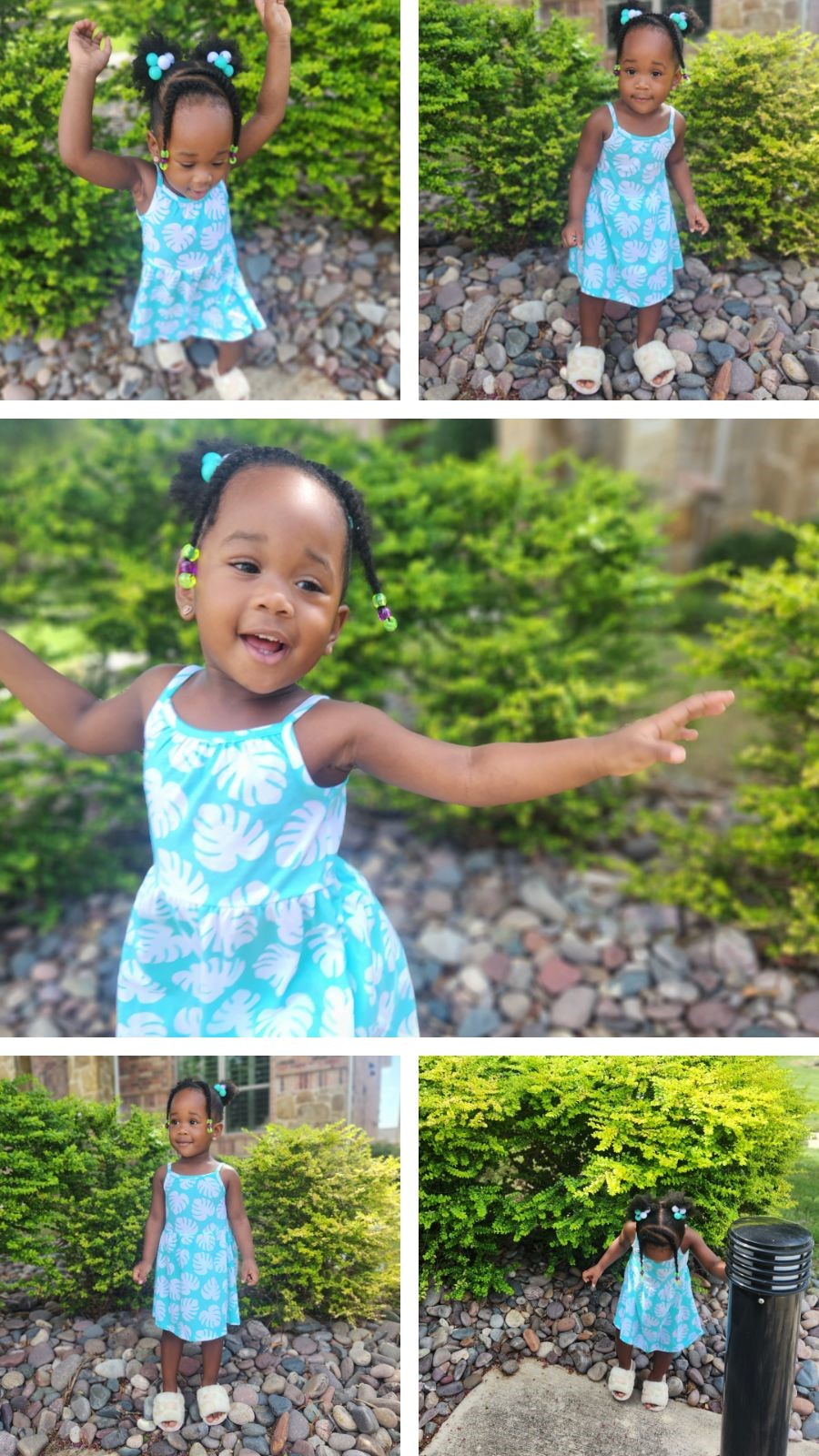

- Toddler photo montage © Chetamia Holmes is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Princess Early Childhood-1 © Kierra Sayrie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Middle childhood – 1 © Chianti Holmes is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- graduate – ch 1 © Michael Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- early adulthood – ch1 © Adrian Celestine is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- middle adulthood ch1 © Fritzi Prejean is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Late adulthood -ch 1 both is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- death – ch1 © Tremika Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Life Span Growth and Development studies how and why people change or remain the same over time.

Culture is often referred to as a blueprint or guideline shared by a group that specifies how to live.

Ethnocentrism is the belief that our culture’s practices and expectations are superior to others.

Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that culture.

Prenatal development is when conception occurs, and development begins.

Infancy and toddlerhood are the first year and a half to two years of life, and dramatic growth and change occur.

Early childhood is the preschool years that follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling.

Middle Childhood is the ages of six through eleven, and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school.

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change that begins with puberty and ends with the transition to adulthood (approximately ages 10–20).

Middle Adulthood is a period in which aging, which began earlier, becomes more noticeable and a period at which many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work. This age group is between the late thirties and mid-sixties.

Late adulthood is categorized and distinguished between the “young old” people between 65 and 79 and the “old-old” or those who are 80 and older.

Death and dying is a phenomenon that discusses various matters that take place at the end of the lifespan.