Chapter 11: Death, Dying, and Bereavement

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the leading causes of death in the United States and compare them with those in Louisiana.

- Describe different theories of grief.

- Differentiate between palliative care and hospice.

- Compare euthanasia, passive euthanasia, and physician-assisted suicide.

- Characterize bereavement, mourning, and grief.

How Long Can We Expect to Live?

According to the National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System, in 2021, life expectancy at birth was 76.4 years for the total U.S. population—a decrease of 0.6 years from 77.0 years in 2020. For males, life expectancy decreased by 0.7 years, from 74.2 in 2020 to 73.5 in 2021. For females, life expectancy fell by 0.6 years, from 79.9 in 2020 to 79.3 in 2021 (Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, Arias, 2021).

In 2021, the difference in life expectancy between females and males was 5.8 years, an increase of 0.1 years from 2020. In 2021, life expectancy at age 65 for the total population was 18.4 years, a decrease of 0.1 years from 2020 (Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, Arias, 2021).

What Are the Death Rates for the Ten Leading Causes of Death?

In 2021, nine of the ten leading causes of death remained the same as in 2020. The top leading causes in 2021 were heart disease, cancer, and COVID-19.

The list below shows the ten leading causes of death and the number of deaths per category in 2021 in the United States.

-

- Heart disease: 695,547

- Cancer: 605,213

- COVID-19: 416,893

- Accidents (unintentional injuries): 224,935

- Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 162,890

- Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 142,342

- Alzheimer’s disease: 119,399

- Diabetes: 103,294

- Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis: 56,585

- Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis: 54,358

Compare the list above to the ten leading causes of death in Louisiana. If you click the links for each cause of death, you will be taken to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Hover over the interactive map to see how Louisiana compares to the rest of the country.

-

-

- Heart Disease: 12,564

- Cancer: 9,246

- COVID-19: 6,329

- Accidents: 4,489

- Stroke: 2,755

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Diseases: 2,170

- Alzheimer’s Disease: 2,121

- Diabetes: 1,943

- Kidney Disease: 1,109

- Septicemia: 1,052

-

Source: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2/22/2023

What Is Death?

The definition of death has changed over time. Death refers to the permanent cessation of life in an organism. Historically, death was determined by the lack of a heartbeat or respiration. However, medical advancements in life support systems such as ventilators, respirators, and other sustaining systems have made it more complicated to declare someone dead. The Uniform Determination of Death Act attempts to provide clarity for clinically defining death in most states throughout the United States with the following: An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made by accepted medical standards.

While the concept of death is universal, there are various classifications of death based on different factors. One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological and social deaths. These deaths do not coincide. Instead, a person’s physiological death and social death can occur at different times (Pattison, 1977).

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function (Beyer et al., 2019). The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive tract loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful. Circulation slows, and mottling or blood pooling may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallower and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus-filled passageways. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although he continues to hear.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death (Pattison, 1977). Social death occurs when others start to withdraw from someone terminally ill or diagnosed with a terminal illness (Glaser & Strauss, 1966). At the end of their life, those individuals may find that friends, family members, and even healthcare professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently (Beyer & Lazzara, 2019). Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals trained to heal may feel bad and uncomfortable facing decline and death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is essential for quality of life, and those who experience social death are deprived of the benefits of loving interaction with others.

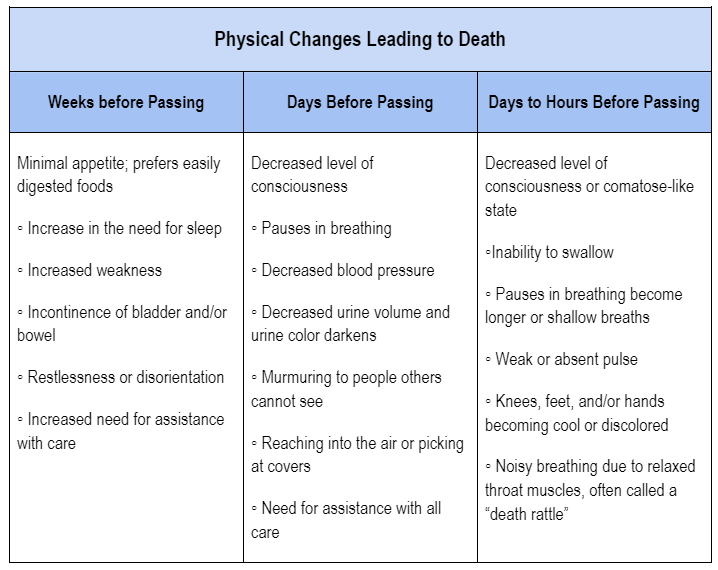

The Process of Death: It is essential to recognize and understand the natural changes associated with the dying process. Recognizing the signs helps to best respond to the transitioning person. Each person is unique; therefore, they may not experience every symptom. Likewise, the timeline is an estimate; there is a firm expectation of when these symptoms will occur.

What’s important to understand is that the body prepares itself for death. Often, loved ones may want to fight this progression. However, some people find peace in allowing this process to occur uninterrupted. For example, in response to the decreased fluid and food consumption, offer smaller meals, ice chips, popsicles, or glycerin swabs. It will be stressful for the individual to continue to force food and liquids during this phase. Likewise, you may notice an increase in sleeping and a decrease in communication. This is due, in part, to a decrease in metabolism, which is also connected to a lesser desire for food. To support your loved one, sit with them and speak softly when talking. There is no need to feel pressured to speak or have them speak to you. Your presence is enough.

One symptom of death that may be distressing to the loved one is the accumulation of fluids at the back of the throat for the transitioning person, which may lead to a gurgling sound (often referred to as the death rattle). This occurs because the body loses the ability to clear these fluids. The best way to assist may be to raise the head of the bed and position the head so that it’s easier for the fluids to drain from the mouth. This sound may be hard to hear. If this sound causes an emotional reaction from you, it may be best to exit the room. Your emotional response may create stress for the dying person.

It is believed that dying people try to “hold on” to ensure the remaining people are okay. Sometimes, it may be necessary to permit the dying person by reassuring them that all will be okay. This process does not need to be dramatic, but it is reasonable to cry while saying goodbye. Holding hands, sitting or lying on the bed beside the person, and praying are good behaviors.

Responses to the dying process will vary based on cultural and religious beliefs. It is important to remember that all parties’ physical, emotional, and spiritual needs are met. However, the needs of the person who is dying hold precedence.

What Are Some of Our End-of-Life Decisions?

The pervasive culture in the United States tends to reject the idea of death. We spend millions of dollars each year engaging in behaviors like plastic surgery and beauty treatments to appear younger because we associate youth with vitality and good health. We also tend to accept every medical treatment available to prolong our life. But what happens when we no longer respond to medical care? What are our options when medicine is not able to restore our health? There comes a point when we are at the end of our lives.

Because we tend to reject death-related topics, we don’t often think about what happens when curative treatment is no longer working or desirable to the patient. This section describes several available end-of-life options.

What Are Palliative Care and Hospice?

When curative treatment is no longer working or desired by a patient, palliative care or hospice service provides patients and their families with the means to continue with “life” through the death of the patient and beyond.

Palliative care, or palliative medicine, is a specialized healthcare approach that relieves the symptoms, pain, and stress associated with advanced or life-threatening illnesses (Dickerson, Khalsa, McBroom, & et al., 2022). The World Health Organization (WHO) describes palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering using early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other issues, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.” It is comprehensive and multidisciplinary, including physicians, nurses, occupational and physical therapists, psychologists, social workers, chaplains, and dietitians. Palliative care can be provided in various contexts, including hospitals, outpatients, skilled nursing, and home settings. It can be provided as the primary goal of care or in tandem with curative treatment.”

Palliative care is distinct from hospice care, although they share some similarities. [Hospice care] is a specific type of palliative care typically provided in the final stages of a terminal illness when curative treatments are no longer effective or desired. Hospice care is focused on providing comfort and support to patients nearing the end of life and their families. Palliative care, on the other hand, can be provided at any stage of a severe illness, regardless of the prognosis. It is essential to acknowledge that hospice is a multidisciplinary program of care, not a place. People may receive hospice care in a hospice facility, at a nursing home, in a hospital, or in their own home. Hospice involves caring for dying patients by helping them be as free from pain as possible, providing them with assistance to complete wills and other arrangements for their survivors, giving them social support through the psychological stages of loss, and helping family members cope with the dying process, grief, and bereavement. To enter hospice, a patient must be diagnosed as terminally ill with an anticipated death within six months. Most hospice care does not include medical treatment of disease or resuscitation, although some programs also administer curative care. The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments.

The modern hospice movement is traced back to London and Dame Cicely Saunders. She believed that dying people should be given autonomy of choices about their lives, allowed to live fully without being ostracized, and offered the mechanisms to die peacefully in comfort. Early hospices were independently operated and dedicated to giving patients as much control over their death process as possible. As of 2018, more than 4,700 hospice programs provide care to over 1.6 million patients (Sengupta, Lendon, Caffrey, Melekin, & Singh, 2022). Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over their services, and lengths of stay are more limited.

Late-stage cancer patients (29.6% in 2018) utilize hospice most often but typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks before death. Alzheimer’s, Dementia, and Parkinson’s patients averaged the most days of care, averaging 105.2 days of care. However, the average stay is less than 30 days, with many patients in hospice for seven days or less (National Center for Health Statistics, 2022).

In the late 1960s, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross began researching death in the United States. She marked the entrance of the hospice movement in her book, “On Death and Dying,” published at about that time. Kübler-Ross outlined five psychological stages of overcoming one’s terminal illness. These “stages” can occur more than once, in different orders, or not at all. The five psychological stages include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This theory of loss helps understand what hospice patients may be experiencing.

Do We Have a Right to Decide When to Die?

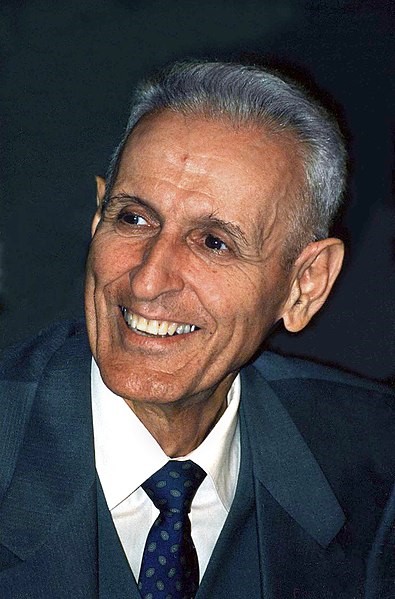

When people discuss the right to die or death with dignity, they discuss physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. These topics are highly debated and controversial issues in the United States. At the crux of this argument is what do we value, quality or quantity of life for humans? We euthanize our pets when they no longer have a good quality of life. But is it amoral for humans to have this same relief from suffering? Read the descriptions below and decide what you believe about an individual’s right to die with dignity.

Euthanasia: Euthanasia, also known as mercy killing, intentionally ends someone’s life to relieve their suffering. It may be carried out with the consent of the individual (active euthanasia) or in cases where the person is unable to provide consent (passive euthanasia) (Allan & Allan, 2020). Active euthanasia involves the intentional act of causing the death of a person, usually to relieve their suffering. It typically involves administering a lethal dose of medication or taking a deliberate action that directly leads to the person’s death. Active euthanasia is carried out explicitly to end the person’s life. In euthanasia, a physician (or someone else) administers a lethal drug (Barsness, Regnier, Hook, et al., 2020). Passive euthanasia, on the other hand, refers to withholding or withdrawing medical treatment or life-sustaining measures necessary to keep a person alive (Allan & Allan, 2020). In passive euthanasia, the intention is not to cause the person’s death directly but to allow nature to take its course or to respect the individual’s wishes to refuse or discontinue treatment. Euthanasia is illegal throughout the United States (Barsness, Regnier, Hook, et al., 2020).

Physician-Assisted Suicide: Physician-assisted suicide occurs when a physician prescribes how a person can end their life. In physician-assisted suicide, a patient ingests a drug prescribed by a physician to cause the patient’s death to relieve unacceptable symptoms or quality of life (Barsness, Regnier, Hook, et al., 2020). The patient, not the doctor or a family member, must administer the lethal medication dosage. The Oregon Death with Dignity Act of 1997 was the first legislation to grant physicians the right to prescribe life-ending medication to their life due to unbearable suffering (Oregon Health Services, 2010). Physician-assisted suicides are rare. In the United States, physician-assisted suicide is legal in California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, and the District of Columbia. Physician-assisted suicide is also legal in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium. Other U.S. states prohibit physician-assisted suicide and punish it by law (Barsness, Regnier, Hook, et al., 2020).

There is a growing number of the population who support physician-assisted suicide. In 2000, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling upheld the states’ rights to determine their laws on physician-assisted suicide despite efforts to limit physicians’ ability to prescribe barbiturates and opiates for their patients requesting the means to end their lives. The position of the Supreme Court is that the right to die with dignity is not a constitutional right, but the debate concerning the morals and ethics surrounding the right to die should be continued (Stein, 2000). Laws concerning physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are generally more rigid in the United States than in countries where physician-assisted suicide is legal. For instance, in the Netherlands, physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are legal for adults (or persons aged 12 through 17 years with parental involvement). Currently, no U.S. state allows physician-assisted suicide for persons younger than 18 years, and physician-assisted suicide is illegal without a severe physical ailment that will result in natural death within six months (Barsness, Regnier, Hook, et al., 2020). As an increasing population enters late adulthood, the emphasis on giving patients an active voice in determining certain aspects of their death is likely.

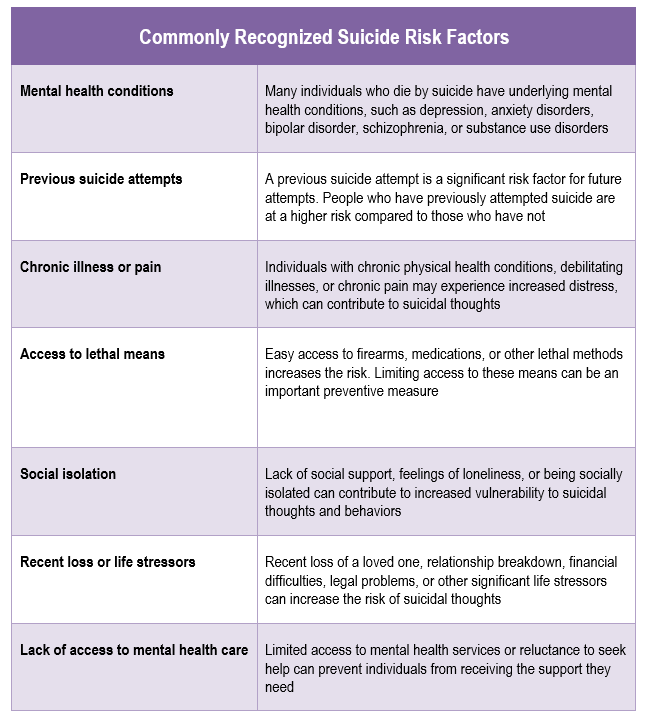

Suicide: Suicide is death caused by injuring oneself intending to die. A suicide attempt is when someone harms themselves with any intent to end their life, but they do not die because of their actions (CDC, 2022). Suicide risk is complex and often influenced by multiple factors. Understanding these risk factors can help identify individuals at a higher risk and enable early intervention and support.

Likewise, certain demographic groups tend to have higher rates of suicide. Historically, suicide rates have been higher among males than females, although rates among females have been rising recently (CDC, 2022). These groups are at the highest risk for suicide:

- Veterans have an adjusted suicide rate 57.3% greater than the non-veteran U.S. adult population. In 2020, 6,146 veterans died by suicide.

- Suicide is the 9th leading cause of death among Tribal populations.

- Adults (35-64 years) account for almost half (46.8%) of all suicides in the U.S.

- Non-Hispanic White men aged 75 and older (50.1 per 100,000) have the highest suicide rate compared to other racial/ethnic men in this age group.

- High school students identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual attempt suicide at a rate five times higher (26.3%) than heterosexual students (5.2%).

- Suicide rates are highest among men working in specific industries:

- Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction (males: 54.2 per 100,000)

- Construction (males: 45.3 per 100,000)

- Other Services (such as automotive repair; males: 39.1 per 100,000)

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting (males: 36.1 per 100,000)

- Transportation and Warehousing (males: 29.8 per 100,000; females: 10.1 per 100,000)

- Adults with disabilities are three times more likely to report suicidal ideation than adults without disabilities (30.6% versus 8.3% in the general U.S. population).

Suicide is a significant public health issue in the United States. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2022), suicide rates increased by approximately 36% between 2000–2021. Suicide was responsible for 48,183 deaths in 2021, about one every 11 minutes (CDC, 2023). The number of people who think about or attempt suicide is even higher. In 2021, an estimated 12.3 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.5 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.7 million attempted suicide.

It is crucial to approach discussions about suicide with sensitivity and to prioritize mental health and well-being. If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of self-harm or suicide, it’s essential to seek help from a mental health professional or a helpline immediately. In the United States, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255), and they provide 24/7, accessible, and confidential support for people in distress, as well as prevention and crisis resources for individuals and their loved ones.

Models of Grief

Thanatology is the scientific study of death, dying, and the processes surrounding them. It is an interdisciplinary field encompassing various disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, medicine, philosophy, and religious studies. Thanatology seeks to understand and explore the physical, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of death and dying and their impact on individuals and societies. People who study death, dying, and the processes surrounding them are called thanatologists. Through the efforts of thanatologists, several models have been developed to describe the grief process and coping mechanisms in dealing with the death of a loved one.

The first theory presented will be that of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross. Though widely criticized, her theory is a foundation on which other scholars have based their research and developed their theoretical models. While Kübler-Ross’ model was restricted to dying individuals, subsequent theories focused on loss as a more general construct. This suggests that facing one’s death is just one example of the grief and loss that human beings can experience and that other losses or grief-related situations tend to be processed (Lane et al., n.d.) similarly.

Stages of Loss: Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (1975) described five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending death. These “stages” are not stages that a person goes through in order or only once, nor do they occur with the same intensity. Nevertheless, these stages provide a framework to help us understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically. And by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die (Lane et al., n.d.).

Kübler-Ross described five of them in detail:

- Denial – “No, not me; it cannot be true.”

- Anger – “Why me?”

- Bargaining – attempting to turn the situation around by entering into “agreements.”

- Depression – when reacting to their illness and preparing for their death.

- Acceptance – developing a realistic understanding of the illness and preparing by looking forward.

As people move through these stages, they attempt to make sense of their diagnosis and the time they have left. These stages represent the cognitive defense mechanisms the individual employs to alleviate their impending death’s stress and psychological trauma.

Dual Process Model of Bereavement: The Dual Process Model, proposed by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut (1999), recognizes that grieving individuals often oscillate between two dimensions of coping with loss:

- Loss-Oriented Coping: This dimension involves actively confronting and experiencing the emotions related to the loss. It encompasses expressing grief, reminiscing, and focusing on the deceased or the loss.

- Restoration-Oriented Coping: This dimension focuses on adapting to the practical and functional changes brought about by the loss. It involves mastering new tasks previously handled by the deceased, reorganizing one’s life, pursuing personal goals, and developing new routines.

According to this model, individuals move back and forth between these two dimensions as they navigate the grieving process. This oscillation allows individuals to balance the need to confront their emotions with the need to attend to the practical demands of life. This model reduces the dynamic whereby the bereaved must choose between “letting go” or “holding on.”

Meaning Reconstruction Model: The Meaning Reconstruction Model, developed by Robert Neimeyer (2002), emphasizes how individuals reconstruct a world and its meaning that a significant loss has changed as a means to adapt and adjust. This model features three mechanisms through which bereaved individuals engage in the process of meaning reconstruction:

-

- Sense-making refers to attempts to comprehend the loss or find reasons for what has happened.

- Benefit-finding denotes encountering growth through grief, valuing life lessons in the experience, and reordering life priorities.

- Identity change occurs when profound loss challenges the coherence of bereaved individuals’ self-narrative, prompting them to relearn the self as they relearn the world.

The Meaning Reconstruction Model highlights the ongoing process of finding meaning and creating a new narrative incorporating loss into one’s life.

Four Tasks of Mourning: William Worden (2008) believes that people must make choices for healthy grieving that require each person to engage with their grief and adapt. In his work, he identified four tasks that facilitate the mourning process. Worden believes all four tasks must be completed, but they may be completed in any order and for varying amounts of time. These tasks include:

- Acceptance that the loss has occurred

- Working through the pain of grief

- Adjusting to life without the deceased

- Starting a new life while still maintaining a connection with the deceased

Overall, these models provide frameworks for understanding the grieving process, but it’s important to remember that grief is a highly individual and complex experience. People may have unique ways of experiencing and coping with grief, and the models serve as general guidelines rather than rigid templates.

How Are Bereavement, Mourning, and Grief Different?

The terms grief, bereavement, and mourning are often used interchangeably; however, while they are related, they encompass different aspects of the grieving process. Bereavement is the objective experience of loss. It is being deprived of someone important, such as the death of a loved one or the end of a relationship. Bereavement is the initial recognition and acknowledgment of the loss. It is a long-term, complex adjustment period where the survivor experiences emotional and behavioral responses to loss as part of coping. During this period, the survivors may experience anxiety and sadness, need to redefine their roles as they adjust to the loss of income or increase in household tasks, or search for meaning as they adjust to life without their loved one. Grief and mourning occur during bereavement. Grief is the emotional reaction to loss. Grief can be in response to a physical loss, such as a death, or a social loss, including a relationship or job. It is the individual’s internal and personal experience of sadness, anguish, and longing triggered by grief. Grief can manifest in various ways, including sadness, anger, guilt, confusion, yearning, and physical and emotional symptoms. It is a highly individual and unique experience influenced by factors such as personal coping mechanisms, cultural background, and the nature of the relationship with the lost person or thing.

Mourning is the process by which people adapt to a loss. Mourning is greatly influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and rituals (Casarett, Kutner, & Abrahm, 2001). It involves the rituals, customs, behaviors, and practices in which individuals or communities express their sorrow and cope with the loss. Mourning can vary across cultures, including funeral ceremonies, wearing black attire, observing specific religious or cultural practices, or engaging in personal rituals to honor the deceased.

In other words, bereavement refers to the experience of loss, mourning encompasses the external expressions and rituals associated with grieving, and grief refers to the internal emotional and psychological response to the loss. These terms collectively describe individuals’ multifaceted and complex process when faced with a significant life loss.

Again, grief refers to the internal emotional and psychological response to the loss and its byproducts. Typical grief reactions involve mental, physical, social, and emotional responses. These reactions include numbness, anger, guilt, anxiety, sadness, and despair. The individual can have trouble concentrating, sleep and eating problems, loss of interest in pleasurable activities, physical issues, and even illness. Research has demonstrated that grief can result in suppressed immune systems and greater susceptibility to illnesses (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010). Grief symptoms typically diminish within 6-10 weeks (Youdin, 2016).

Complicated Grief: After the loss of a loved one, some individuals experience complicated grief, which includes atypical grief reactions (Newson, Boelen, Hek, Hofman, & Tiemeier, 2011). Symptoms of complicated grief include an intense yearning for the person who died, frequent thoughts or images of the deceased person, intense loneliness or emptiness, and a feeling that life without this person has no purpose or meaning. Complicated grief may also lead to dysfunctional thoughts, maladaptive behaviors, and emotional dysregulation (Shear et al., 2011). These symptoms may last six months or longer and mirror those seen in major depressive disorder. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), distinguishing between major depressive disorder and complicated grief requires clinical judgment. The psychologist needs to evaluate the client’s history and determine whether the symptoms are focused entirely on the loss of the loved one and represent the individual’s cultural norms for grieving, which would be acceptable. Those who seek assistance for complicated grief usually have experienced traumatic forms of bereavement, such as unexpected, multiple, and violent deaths or those due to murders or suicides (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Disenfranchised Grief: Grief that is not socially recognized is called disenfranchised grief (Doka, 1989). Examples of disenfranchised grief include death due to a stigmatized disease; the suicide of a loved one; perinatal deaths; abortions; the death of a married lover, ex-spouse, best friend, or pet; and psychological losses, such as a partner developing Alzheimer’s disease. There are no formal mourning practices or recognition by others that would comfort the grieving individual. People may feel the need to hide the circumstances of their loss or their grief going unrecognized by others. Consequently, individuals experiencing disenfranchised grief may suffer intensified symptoms due to a lack of social support (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Anticipatory Grief: Grief occurs when a death is expected, and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss, referred to as anticipatory grief. This expectation can adjust to a loss somewhat easier (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over, and the exhausting process of caring for someone ill is also complicated.

Conclusion

Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler (2005, p. 205) wrote about the “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” where we are expected to grieve privately and quickly and to medicate our suffering. Employers grant us 3 to 5 days for bereavement if our loss is that of an immediate family member. Often, such leave is limited to no more than one per year. Yet, grief takes much longer, and the bereaved are seldom ready for public interaction or to perform well on their job. Kübler-Ross and Kessler suggest that contemporary American society would acknowledge and make more caring accommodations for those grieving.

Watch It

Drake University sociologist Nancy Berns argues that closure, a fabricated concept, may be causing more harm than good in the space between grief and moving on.

Death and grief are topics that are being given more significant consideration. This trend should continue as the population “grays,” and our awareness of natural disasters and war grows in the United States and worldwide. Viewing death as an integral part of the lifespan will benefit those who are ill, those who are bereaved, and all of us as friends, caregivers, partners, family members, and humans in a global society.

The following strategies have been identified as effective in support of healthy grieving:

- Talk about death. This will help the surviving individuals understand what happened and positively remember the deceased. When coping with death, getting wrapped up in denial can be easy, leading to isolation and a lack of a solid support system.

- Accept the multitude of feelings. The death of a loved one can, and almost always does, trigger numerous emotions. It is normal for sadness, frustration, and sometimes exhaustion to be experienced.

- Take care of yourself and your family. Remembering to prioritize one’s health and the health of one’s family can help a person move through each day effectively. Making a conscious effort to eat well, exercise regularly, and obtain adequate rest is essential.

- Reach out and help others dealing with the loss. It has long been recognized that helping others can enhance one’s own mood and general mental state. Assisting others to cope with the loss can have this effect, as can sharing stories of the deceased.

- Remember and celebrate the lives of your loved ones. This can be a great way to honor the relationship that was once had with the deceased. Possibilities can include donating to a charity the deceased supported, framing photos of fun experiences with the dead, planting a tree or garden in memory of the deceased, or anything else that feels right for the particular situation.

Louisiana Snapshot

Funerals & Second Lines

Jazz funerals are a big part of New Orleans culture, and with jazz funerals come Second Line parades. The second line is commonly associated with New Orleans culture, particularly about music, parades, and celebrations. It refers to traditional dancing and marching during lively street parades, notably during jazz funerals and other festive occasions in New Orleans.

The second line has two main components: the “first line” and the “second line.”

- First Line: The first line consists of the prominent participants in the parade. This typically includes the family, the hearse, and a brass band, often playing traditional New Orleans jazz or brass band music. The band leads the procession to the cemetery, playing sad music and then away from the graveyard, playing energetic and rhythmic music to celebrate the deceased’s life.

- Second Line: The second line refers to the people who follow behind the first line, joining in the procession as it goes through the streets, dancing and celebrating. Second-line participants often carry umbrellas, handkerchiefs, or parasols, and they engage in various dance steps and movements, often characterized by a distinctive footwork known as “second-line dancing.” The dancers energetically move and sway to the music, constantly improvising their steps while maintaining the rhythm and spirit of the parade.

The second line tradition has deep roots in West African and African American cultural traditions and has become integral to New Orleans’ rich cultural heritage. Second-line parades are not limited to jazz funerals; they can also be seen during weddings, festivals, and other joyous events throughout the city. These parades often involve lively music, vibrant costumes, and a sense of community celebration, encouraging participants and onlookers alike to join the festivities.

The second line embodies the spirit of joy, resilience, and collective expression that is central to the cultural fabric of New Orleans, making it a cherished and unique tradition in the city’s cultural landscape. In the YouTube video above, locals celebrate the life and music of Lois Nelson-Andrews from 2021. Source: Courtesy of WWOZ. The video includes no dialogue and therefore does not include captions or a transcript.

References

Allan, A., & Allan, M. M. (2020). Ethical issues when working with terminally ill people who desire to hasten the ends of their lives: a Western perspective. Ethics & Behavior, 30(1), 28–44. https://doi-org.ezproxy2.lsua.edu/10.1080/10508422.2019.1592683

Barsness, J. G., Regnier, C. R., Hook, C. C. et al. US medical and surgical society position statements on physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: a review. BMC Med Ethics 21, 111 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00556-5

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018–2021 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2023. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018–2021, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-expanded.html on Jan 11, 2023

Dickerson, S. S., Khalsa, S. G., McBroom, K., White, D., & Meeker, M. A. (2022). The meaning of comfort measures only order sets for hospital-based palliative care providers—International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17(1). https://doi-org.ezproxy2.lsua.edu/10.1080/17482631.2021.2015058

Doka, K. (1989). Disenfranchised grief. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1966). Awareness of dying. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. [New York]: Macmillan.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1975). Death: The final stage of growth. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Neimeyer, R. A. (2002). The relational co-construction of selves: A postmodern perspective. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 32, 51–59. doi:10.1023/A:1015535329413

Newson, R. S., Boelen, P. A., Hek, K., Hofman, A., & Tiemeier, H. (2011). The prevalence and characteristics of complicated grief in older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 132(1-2), 231-238.

Oregon Health Services. (2010a). Death with Dignity Act. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/citizen_engagement/Reports/DeathwithDignityAct.pdf

Parkes, C. M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2010). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life (4th ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Pattison, E. M. (1977). The experience of dying. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Sengupta, M., Lendon, J. P., Caffrey, C., Melekin, A., Singh, P. Post-acute and long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2017–2018. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3(47). 2022. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:115346.

Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., Reynolds, C., Lebowitz, B., Sung, S., Ghesquiere, A., Gorscak, B., Clayton, P., Ito, M., Nakajima, S., Konishi, T., Melhem, N., Meert, K., Schiff, M., O’Connor, M. F., First, M., Sareen, J., Bolton, J., Skritskaya, N., Mancini, A. D., Keshaviah, A. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. (2011). Feb;28(2):103-17. doi: 10.1002/da.20780. PMID: 21284063; PMCID: PMC3075805.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2022). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22-07-01-005, NSDUH Series H-57). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report

Stroebe, S. and Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 3: 197-224.

“WHO Definition of Palliative Care.” WHO. Archived from the original on Oct 4, 2003, and retrieved May 4 28, 2023.

Worden, J. W. (2008). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.). New York: Springer Publishing company

Xu, J. Q., Murphy, S. L., Kochanek, K.D., Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, no 456. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:122516.

Attribution:

Original content authored by Dr. Cynthia Thomas in addition to portions of this chapter adapted by Dr. Cynthia Thomas from select chapters in Lumen Learning’s Lifespan Development, authored by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license, and Waymaker Lifespan Development, written by Sarah Carter for Lumen Learning and available under a Creative Commons Attribution license. Some selections from Lumen Learning were adapted from previously shared content from Laura Overstreet’s Lifespan Psychology and Wikipedia.

Cynthia Thomas, PhD contributed the following changes to this chapter:

- The addition of Louisiana cultural information. This chapter has a cultural opener and closer as well as Louisiana specific statistics throughout.

- Statistics throughout the chapter have been updated to the most recent data available. In many cases, links have been provided to the originating source.

- Included an explanation of the Uniform Determination of Death Act that was created to provide legal guidance for determining when a death has occurred.

- Expanded the Process of Death section to include a chart entitled Physical Changes Leading to Death to bring awareness to changes that are typical as a person approaches end of life.

- Expanded the discussion about end-of-life decisions to include information about palliative care, hospice, and physician assisted suicide. This discussion provides insight to the decision-making process involved in determining how to best allow your loved one to transition with dignity.

- Included information on suicide. Help seeking information also provided.

- Expanded the Models of Grief section to include work by 4 theorists and a description of thanatology. This section is written in a way that allows the reader to understand that the study of death and dying is a research base field.

- Further delineated between bereavement, mourning, and grief so the reader understands that these terms are not interchangeable.

- Developed assignments to aid in understanding material presented in this chapter and to increase exposure to internet-based support groups and learning aids.

Media Attributions

- 800px-Dia_de_los_Muertos_Celebration_in_Mission_District_of_San_Francisco,_CA © Jared Zimmerman (WMF) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- St._Louis_Cemetery_No._3._New_Orleans._4882 © Bernard Spragg is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- obesity © Tony Alter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Ch11 – phys changes to death © Angie Balius is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- hospice-caring-elderly-old © PX Fuel is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Jack_Kevorkian_National_Press_Club © KingKongPhoto is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Suicide Risk Factors chart © Cynthia Thomas is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- claudia-wolff-owBcefxgrIE-unsplash (1) © Claudia Wolff is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 2060418469_9ab4bf8123 © Derek Bridges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license