Chapter 8: Early Adulthood

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the concept of emerging adulthood and how it differs from adolescence

- Be familiar with the characteristics of early adulthood physical development

- Be familiar with the characteristics of early adulthood cognitive development

- Be familiar with the characteristics associated with early adulthood psychosocial development

- Understand how culture plays a role in early adulthood development

- Be familiar with the theoretical development stages that take place during early adulthood

- Be familiar with the common factors associated with academic or career achievement for early adulthood and the potential barriers they face to success

- Be familiar with relationships during early adulthood

Louisiana Snapshot

Laissez Le Bon Temps Rouler!

Louisianians often use the French Creole phrase “Laissez Le Bon Temps Rouler,” which means “Let the Good Times Roll.” This motto can resonate with those entering early adulthood as they begin to experience newfound freedoms that allow them to live according to their choices without much input or consensus from outside influences. In this age group, there is a tendency to explore one’s identity, which can often involve engaging in risky behaviors. It is, therefore, essential to navigate this phase sensibly and responsibly. So, by all means, let the good times roll, but do so in a way that doesn’t put your safety at risk.

How Do You Define Early Adulthood?

The trend of prolonging adolescence has led to a new developmental phase called emerging adulthood. This phase occurs from ages 18 to 29 and captures the transition from adolescence to adulthood. In the past, most people in this age group had already entered stable adult roles, including romantic relationships and work. However, today’s young adults in industrialized societies are taking longer to achieve early adulthood developmental tasks, such as completing formal education, financial independence from their parents, marriage, and parenthood. This has brought about a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these changes. Emerging adulthood is when many different directions remain possible, and the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is more significant than at any other period of the life course (Arnett, 2000).

Arnett identified the distinguishing characteristics of emerging adulthood: a prolonged transitional period that sets it apart from adolescence and young adulthood.

- Identity Exploration – Erik Erikson commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs in the late teens and early twenties rather than adolescence. During emerging adulthood, many people are exploring their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood. Part of that exploration is attending postsecondary (tertiary) education to expand more pathways for work. Tertiary, or post-secondary, education includes community colleges, universities, and trade schools.

- Instability – Exploration generates uncertainty and instability. Arnett, in 2006, states that emerging adults tend to change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life. This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out to be independent. They may move again when they drop out of college, change trade schools, or graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents or guardians at least once. In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ homes rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships.

- Self-Focused – Emerging adults are different from adolescents in that they tend to be less self-centered and more empathetic towards others, especially their parents. During this stage, they focus on themselves, make independent decisions about their lives, and develop the skills, knowledge, and self-understanding they need for adult life. This sense of independence can be seen in different cultures, whether they move out of their parents’ homes or not.

- Feeling In-Between – Most emerging adults have already experienced puberty and no longer attend high school. Many have also moved out of their parent’s homes, which makes them feel less dependent than they were as teenagers. However, they may still rely on their parents or primary caregivers for financial support to some extent, and they have not achieved specific markers of adulthood, such as finishing their education, securing a full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It’s not surprising that Arnett discovered that about 60% of 18-to-25-year-olds felt like adults in specific ways but not in others (Arnett, 2004). Most people feel like they have reached adulthood in their late twenties or early thirties. This “in-between” feeling during emerging adulthood has been observed in several countries, including Argentina, Austria, Israel, the Czech Republic, and China.

- Many Possibilities – Individuals tend to have high expectations and optimistic hopes during emerging adulthood. In a national survey conducted in the United States, about 89% of 18- to 24-year-olds agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life.” This positive outlook is also reflected in other countries. Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested. This stage of life allows individuals to change the direction of their lives. The choices and decisions of primary caregivers heavily influence the experiences of children and adolescents. If the primary caregivers are dysfunctional, the child has little control over it. However, in emerging adulthood, people can move out and away from unhealthy environments and transform their lives. Even those who had a happy and fulfilling childhood can become independent and decide the direction they want their life to take.

Watch It

If you are interested in understanding the concept of emerging adulthood and why it seems to take longer to reach adulthood in developed nations nowadays, you may find it helpful to watch this video featuring Dr. Jeffrey Arnett. In the first six and a half minutes of the video, Dr. Arnett discusses four societal revolutions that may have contributed to the emergence of this life stage. Later in the video, he explains why “30 is the new 20” and how young adults today have more freedom than previous generations.

A transcript of this video is available online. (opens in new window).

Emerging Adulthood around the Globe

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood were initially based on research involving about 300 Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2003). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

The answer to this question depends significantly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a helpful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The rest of the human population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes, median educational attainment, and a much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in developing countries.

The same demographic changes described above for the United States have also occurred in other OECD countries. This is true of participation in postsecondary education and median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UN Data, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries.

In Europe, emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely (Douglass, 2007). Today, Europe comprises the world’s most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide great unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also offer housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually reaching adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of emerging Asian adults in developed countries such as Japan and South Korea are similar to those of emerging adults in Europe and, in some ways, strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that support them in transitioning to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although many Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades due to globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of most emerging adults.

For young people in developing countries, emerging adulthood typically only exists for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class. In contrast, the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work early and begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. However, as globalization proceeds and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will most likely increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood may be normative worldwide.

Watch It

According to Arnett, a delay in entering early adulthood marks the “emerging adulthood” period, but not everyone shares his opinion. Dr. Meg Jay cautions young adults against procrastination and highlights the significance of the events in their twenties, as these experiences shape their entire adulthood.

What Physical Developments take place In Early Adulthood?

People in their twenties and thirties are considered categorized as young adults. If you are in your early twenties, you are likely at the zenith of your physiological development. Your body has completed its growth, but your brain is still evolving (as explained in the previous module on adolescence). Physically, you are in the “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are functioning at their best. However, these systems will gradually decline, and you will notice signs of aging by the time you reach your mid to late 30s. This includes a decline in your immune system, response time, and ability to recover quickly from physical exertion.

It’s essential to remember that both nature and nurture influence development. Getting out of shape is not an inevitable part of aging; it is probably because you have become less physically active and have experienced more significant stress. The good news is that you can adopt healthier lifestyles and take steps to combat many of these changes. So remember that some of the changes we associate with aging can be prevented or turned around.

Research suggests that the habits we establish in our twenties are linked to specific health conditions in middle age, particularly the risk of heart disease. What healthy habits can young adults develop now that will prove beneficial later in life?

Healthy habits include:

- Maintaining a realistic body mass index

- Moderate alcohol intake

- A smoke-free lifestyle

- A healthy diet

- Regular physical activity

When asked to name one thing that young adults can do to promote good health, experts provided a range of specific recommendations, including learning to cook, reducing sugar intake, developing an active lifestyle, eating vegetables, practicing portion control, establishing an exercise routine, finding a job that one loves, establishing healthy relationships, and creating healthy boundaries.

Health in Early Adulthood

Obesity

Obesity is a medical condition that can be considered a disease characterized by the accumulation of excess body fat that negatively affects health. Maintaining physical health is a top priority for young adults, but the current obesity rate is a concern. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016), obesity is caused by a complex set of factors, including environment, behavior, and genetics. Societal factors such as culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the availability of a physical activity environment can contribute to obesity. Unhealthy behaviors such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, and medication use can also lead to obesity. Although no single gene is responsible for obesity, studies have identified variants in several genes that may contribute to it by increasing hunger and food intake.

Another genetic explanation is the mismatch between the modern-day environment and “energy-thrifty genes” that were beneficial in the past when food sources were scarce. These genes helped our ancestors survive occasional famines but are now challenged by environments with abundant food. Obesity is likely the result of complex interactions between the environment and multiple genes.

Obesity Health Consequences

Obesity is considered to be one of the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide. According to the CDC (2016), compared to those with a standard or healthy weight, people who are obese are at increased risk for many severe diseases and health conditions, including:

- All causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

Louisiana Snapshot

Obesity in Louisiana

Louisiana ranks among the top ten states in the United States—many of which are in the South—for both adult and childhood obesity. Nearly one out of four adults in Louisiana are considered obese (Louisiana Department of Health, n.d.). This statement is not surprising, possibly since food is immersed in almost every area of Louisiana culture. Many Louisiana festivals and gatherings are centered around food. Cuisines cooked in Louisiana are rich in flavor and factors that can lead to obesity if these delicacies are a part of their daily dietary intake. As with any good thing, the best practice would be to enjoy it in moderation. Read more on Adult Obesity Data in Louisiana.

A Healthy but Risky Time

During early adulthood, individuals generally enjoy good health. For instance, in the United States, adults aged between 18 and 44 tend to have the lowest percentage of physician office visits compared to any other age group, regardless of whether they are younger or older. However, this phase of life can be difficult when it comes to violent deaths, with rates varying by gender, race, and ethnicity. The leading causes of death for both age groups, 15-24 and 25-34 in the U.S., are unintentional injuries, suicide, and homicide. Cancer and heart disease follow as the fourth and fifth top causes of death among young adults (CDC, 2022).

Substance Use, Abuse, and Risky Behaviors

Substance use influences violent death rates, which tend to peak during emerging and early adulthood. Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. Drug and alcohol use increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016, followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019, and then an increase in 2020 (CDC, n.d.). Overall, the prevalence of drug use disorders is highest amongst people in their twenties, is consistent across most countries, and is typically related to risky behaviors.

Alcohol Use

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2015), binge drinking is defined as when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. Typically, this happens after four drinks for women and five for men in about two hours. The NIAAA warns that binge drinking can have severe health and safety consequences, such as car accidents, DUI arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Furthermore, frequent binge drinking can cause long-term damage to the liver and other organs.

Alcohol and College Students

Alcohol consumption is a significant factor in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses. Studies have shown that alcohol use is one of the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault in such settings (Carroll, 2016). According to Krebs et al. (2009), alcohol was involved in more than 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses. Unfortunately, many college students tend to perceive perpetrators who drink alcohol as less responsible, while victims who drink are often seen as more accountable for the assaults (Untied et al., 2012). However, it is essential to note that in most states, individuals cannot legally give consent while under the influence of alcohol or other substances.

Factors Affecting College Students’ Drinking

Alcohol consumption is a significant issue for college students, with several factors contributing to their involvement. These include the easy availability of alcohol, the lack of consistent enforcement of underage drinking laws, ample unstructured time, difficulty in coping with stress, and limited interactions with adults such as parents and caregivers. During the first six weeks of their first year, students are particularly vulnerable due to social pressure and expectations of college life. Schools with active Greek systems and athletic programs tend to have higher rates of alcohol consumption. Conversely, students who live with their families and commute have lower rates of alcohol consumption compared to those living in fraternities and sororities.

College Strategies to Curb Drinking

College drinking can be addressed through individual and campus community levels. It is helpful to identify at-risk groups like first-year students, fraternity/sorority members, and athletes and provide them with interventions that aim to change their knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding alcohol. Health professionals can also intervene when needed. At the college level, reducing the availability of alcohol has proven to be effective in decreasing both consumption and negative consequences. Education and awareness programs can also be implemented to raise awareness among students and prevent excessive drinking.

Alcohol Consumption in Louisiana

Excessive drinking is more prevalent in some areas of the United States than in others. In Louisiana, alcohol consumption may start early in life, as it is sometimes permitted as a rite of passage during teenage years at family gatherings and celebrations. Besides, Louisiana residents celebrate their good times with food and alcohol, embodying the Creole phrase “Laissez Les Bon Temps Rouler,” which means “Let the Good Times Roll.” However, Louisiana ranks 21st in alcohol consumption amongst states, with residents consuming 2.59 gallons per person aged 14 and older in 2020, according to data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA, 2022). In comparison, the nationwide alcohol consumption was 2.45 gallons per person in the same year.

The health risks of excessive alcohol consumption extend beyond chronic conditions. A troubling 31.2% of all driving deaths in Louisiana between 2016 and 2020 involved alcohol (Stubbins, 2023).

Nicotine Use

It was estimated that in 2018, around 6.5 million young adults aged between 18 and 25 smoked cigarettes in the past month. This means that roughly one-fifth of young adults (19.1 percent) were current cigarette smokers. However, the percentage of young adults who smoked cigarettes in 2018 was lower than the percentages from the years 2002 to 2017.

According to the CDC (2020), the use of e-cigarettes has become increasingly popular among young adults in the recent past. However, it reached its highest prevalence in 2019 and is slowly declining. It is important to note that e-cigarettes are not safe for kids, teens, and young adults as they can contain other harmful substances besides nicotine, which is highly addictive and can impair brain development at this age. Moreover, young people who use e-cigarettes are more likely to start smoking cigarettes in the future (U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2016). Additionally, the use of e-cigarettes has been linked to severe and fatal lung injuries due to the combination of nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabinoid (CBD) oils, and other substances, flavorings, and additives.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission through sexual behavior, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. Some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person and through childbirth or breastfeeding.

Common STIs include:

- chlamydia;

- herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

- human papillomavirus (HPV);

- gonorrhea;

- syphilis;

- trichomoniasis;

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

The most effective ways to prevent transmission of STIs are practicing abstinence, the ability to refrain from participating in sexual activities, or safe sex by altogether avoiding direct contact with skin and fluids, which can lead to transfer with infected partners. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.

Sexuality

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The natural and physical aspects of sexuality primarily concern human reproductive functions, including the human sexual response cycle and the primary biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality is also impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

Sexual Responsiveness

People tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. Sexual arousal can quickly occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness tends to decline in the late twenties and into the thirties, although they may continue to be sexually active throughout adulthood. Over time, individuals may require more intense stimulation to become aroused.

Sexlessness

There has been a sharp increase in the number of individuals ages 18 to 35 who reported not having sexual intercourse (sexlessness) in the prior year, and it continued into 2021 (Lyman, 2021). This research shows at least two separate trends related to the increase in sexlessness: one is that people are delaying marriage, and the other is the increasing sexlessness among individuals who have never been married.

What Types of Cognitive Development Are Experienced during Early Adulthood?

The study of cognitive development covers the progression of cognitive abilities from infancy through adolescence, culminating in the formal operational stage described by Piaget. However, does this mean that cognitive development ceases to progress after adolescence? Could there be additional thinking methods in adulthood after the formal operations stage?

This section will explore post-formal operational thought and examine research conducted by William Perry on advanced thinking and types of thought. We will also investigate the relationship between education and work in early adulthood and the tools young adults use to select their careers.

Beyond Formal Operational Thought: Post-formal Thought

During the adolescence module, we talked about Piaget’s formal operational thought. This type of thinking is characterized by the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about situations never experienced directly. However, thinking abstractly is only one aspect of adult thought. If you compare a 14-year-old with someone in their late 30s, you will probably find that the latter considers not only what is possible but also what is likely. The young adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. This difference in thought between adults and adolescents can sometimes lead to generational disagreements.

It is important to note that Piaget’s theory of cognitive development concludes with formal operations. However, other ways of thinking may develop after formal operations in adulthood (even if this thinking does not constitute a separate “stage” of development). Post-formal thought is practical, realistic, more individualistic, and characterized by understanding the complexities of various perspectives. As a person approaches their late 30s, they are more likely to make decisions based on prior experience and necessity rather than being influenced by the opinions of others. This is particularly true in individualistic cultures like the United States. Post-formal thought is often described as more flexible, logical, willing to accept moral and intellectual complexities, and dialectical than previous stages of development.

Perry’s Scheme

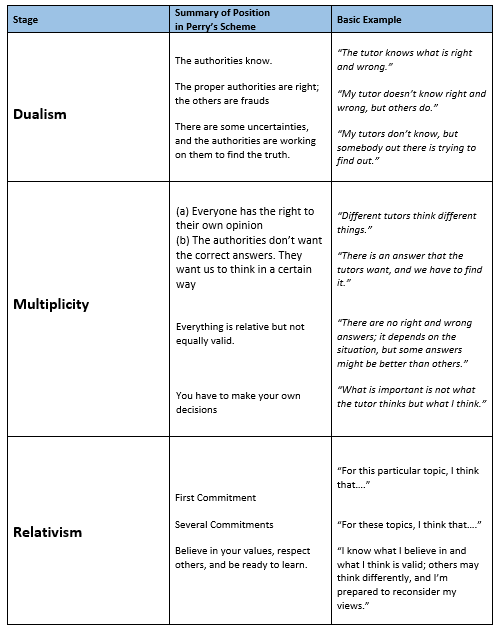

Perry (1998) was one of the first to theorize about cognitive development during early adulthood. In his study of undergraduate students at Harvard University, he observed how their cognition evolved from dualism thinking (which is characterized by absolute, true/false, right and wrong types of thinking) to multiplicity thinking (which recognizes that some problems are solvable and some answers are not yet known) and eventually to relativism thinking (which understands the importance of the specific context of knowledge—it is all relative to other factors). This shift in thinking during early adulthood is similar to Piaget’s formal operational thinking in adolescence, and educational experiences influence it.

Watch It

Please watch this brief lecture by Dr. Eric Landrum to better understand how thinking can shift during college.

Notice the overall shifts in beliefs over time. Do you recognize your thinking or those of others you know in this clip?

Read a transcript of this video.

Dialectical Thought

During early adulthood, individuals tend to think more practically, and their thinking may become more flexible and balanced. In their adolescent years, they tend to think in dichotomies or absolute terms, where ideas are either true or false, good or bad, right or wrong, and there is no middle ground. However, with education and experience, the young adult recognizes that each position has some right and some wrong. This is more realistic because few positions, ideas, situations, or people are right or wrong.

Moreover, some adults may move beyond relativistic or contextual thinking and be able to synthesize essential aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions to come up with new ideas. This is known as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of post-formal thinking. There is no single theory of post-formal thought; variations emphasize adults’ ability to tolerate ambiguity, accept contradictions, or find new problems rather than solve existing ones, among other things. Regardless, they all have one thing in common: how we think may change with education and experience during adulthood.

Dialectical thinking is defined as seeing things from multiple perspectives, a hallmark of post-formal thinking.

What Are Some Psychosocial Experiences That Occur during Early Adulthood?

From a lifespan developmental perspective, growth and development do not stop in childhood or adolescence; they continue throughout adulthood. In this section, we will build on Erikson’s psychosocial stages and then be introduced to theories about transitions that occur during adulthood. More recently, Arnett notes that transitions to adulthood happen later than in the past and proposes a new stage between adolescence and early adulthood called “emerging adulthood.”

Erikson’s Theory

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson (1950) proposed that the primary goal of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and avoid feelings of isolation. Intimacy is not restricted to romantic relationships; it involves caring for another person and sharing oneself without losing one’s identity. This developmental crisis of “intimacy vs. isolation” is influenced by how the adolescent crisis of “identity vs. role confusion” was resolved and how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved. The young adult may be hesitant to get too close to someone and lose their sense of self, or they may define themselves in terms of another person. Intimate relationships are more challenging if one struggles with one’s identity. Although achieving a sense of identity is a lifelong process, there are periods of identity crisis and stability. According to Erikson’s theory, having a sense of identity is crucial for establishing intimate relationships. However, it is worth considering what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages or for contemporary Eastern cultures that value interdependence over independence.

Friendships as a Source of Intimacy

In our twenties, friendships can fulfill intimacy needs while long-term commitments are postponed.

Gaining Adult Status

During early adulthood, many developmental tasks involve gaining independence and becoming part of the adult world. Young adults often feel they are not treated with respect, especially if they are in positions of authority over older individuals. Therefore, they may emphasize their age to gain credibility from slightly younger people. For instance, a young adult might exclaim, “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” It’s worth noting that people in their 40s are less likely to express themselves this way.

In early adulthood, the focus is frequently on the future. Many aspects of life are put on hold while people seek additional education, go to work, and prepare for a better future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve “as soon as I finish school,” “as soon as I get promoted,” or “as soon as the children get a little older.” As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly, and the day may consist of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in a better future.

Adulthood is a period of building and rebuilding one’s life. Many decisions in early adulthood are made before a person has had enough experience to understand their consequences. Additionally, many of these initial decisions are made to be seen as adults. Consequently, early decisions may be driven more by the expectations of others. For example, imagine someone who chose a career path based on others’ advice but now finds that the job is not what was expected.

Temperament and Personality in Early Adulthood

Temperament is defined as the natural characteristics of an infant, such as mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, which are noticeable soon after birth. The question arises whether one’s temperament remains stable throughout one’s life. Does a shy and inhibited baby grow up to be a nervous adult, while a friendly child continues to be the life of the party? The answer is not as simple as a yes or no. Research conducted by Chess and Thomas (1984), who identified children as easy, difficult, slow-to-warm-up, or blended, found that children identified as easy grew up to become well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted. Kagan studied the temperamental category of inhibition to unfamiliarity in children. Infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli, cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and increased their heart rates. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull (2009) found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood.

Although temperamental stability holds for many individuals throughout their lifespan, an individual’s environment can also significantly impact them. Environmental factors are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off, known as epigenesis. Many cultural and ecological factors can affect one’s temperament, including child-rearing practices, socioeconomic status, stable homes, illnesses, teratogens, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that support their temperament, further strengthening them (Cain, 2012).

Personality refers to a person’s characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others. Personality traits refer to the distinctive, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. As a result, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, involving what people value, think, and feel about things, what they like to do, and what they are like almost daily throughout their lives.

Personality can change throughout adulthood. Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age, and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes, including job success, health, and longevity (Roberts et al., 2007).

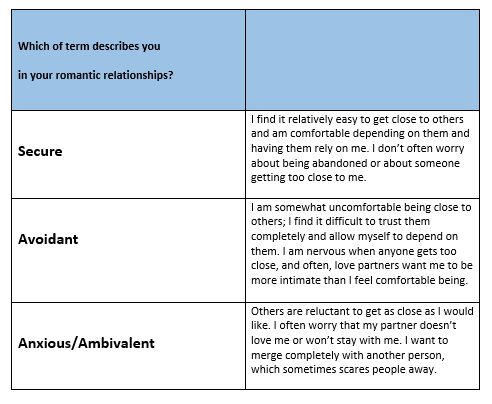

Hazan and Shaver (1987) categorized the attachment styles of adults into three categories: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Their classification was based on the same three categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing one of the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about their romantic relationships and choose the paragraph that best represented their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors in those relationships (as shown in Table 8.3).

However, Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and proposed that adult attachment could be better described as varying along two dimensions: attachment-related anxiety and avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner loves them. Those who score high in this dimension fear their partner will reject or abandon them. On the other hand, attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others and trust and depend on them. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their autonomy. Bartholomew (1990) suggested that this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant.

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves but do not trust others, and thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships but are uncomfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships.

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety tend to report more daily conflict in their relationships.

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support for their partners.

- Young adults tend to show more significant attachment-related anxiety than middle-aged or older adults.

- Some studies report that young adults tend to show more attachment-related avoidance, while others find that middle-aged adults tend to offer higher avoidance than younger or older adults.

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents tend to transition to adulthood more quickly than those with more insecure attachments.

Do People with Certain Attachment Styles Attract Those with Similar Styles?

When seeking a romantic partner, people often desire someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, attributes that describe a “secure” caregiver. However, it is common for people not to end up with someone who meets their ideal preferences. So, are secure individuals more inclined to end up with safe partners and vice versa? The answer seems to be “yes,” according to most research studies.

One crucial question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure individuals are more attracted to other secure individuals, (b) secure individuals tend to instill security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of both factors. Research studies support the first alternative, where individuals tend to express greater interest in more secure individuals when interacting with people who vary in security within a speed-dating context. However, there is evidence that people’s attachment styles influence one another in close relationships.

Do Childhood Experiences Shape Adult Attachment?

Most research on this issue relies on adults’ recollections of childhood experiences. This work suggests that adults with secure attachments tend to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Various longitudinal studies demonstrate that early attachment experiences are associated with adult attachment styles and interpersonal functioning in the future.

It is easy to misunderstand these findings and assume that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. However, attachment theorists believe that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is thought to set the stage for positive social development.

Attachment patterns can change over time, even for individuals who have had far from optimal experiences in early life. Attachment theory suggests that these individuals can develop well-functioning adult relationships through several corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of only the person’s early experiences. While these early experiences are essential, they do not determine a person’s fate. Instead, they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

What Do Relationships Look Like During Early Adulthood?

As per Erikson’s theory, the major psychosocial developmental challenge during early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation.” Successfully resolving this stage can lead to the virtue of “love.” The following section will examine relationships during early adulthood, such as love, dating, cohabitation, marriage, and parenting.

Relationships with Parents, Caregivers, and Siblings

As children grow up, their relationship with their parents must transform into a relationship between two adults. This requires a reevaluation of their relationship by both the parents and the young adults. However, some parents struggle to interact with their grown-up children as adults. This reluctance or inability can prevent young adults from developing their identity. Moving out of home often helps young adults to grow psychologically and become independent.

Sibling relationships are some of the most durable bonds in people’s lives, but there is limited research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood. Research has shown that the nature of these relationships changes since adults can choose whether to maintain a close bond and remain part of each other’s lives. Siblings must also appraise each other as adults, just as parents do with their children. During early adulthood, interactions between siblings reduce as peers, romantic relationships, and children become more critical in the lives of young adults. Nevertheless, it is crucial to maintain a strong enough bond to have a foundation for the relationship in later life. Successful people can move beyond childhood conflicts and establish an equal relationship between two adults. Siblings close to each other in childhood tend to remain tight in adulthood.

Attraction and Love

Attraction

Psychologists have investigated factors influencing attraction, such as similarity, proximity, familiarity, and reciprocity. This research helps explain why some people hit it off quickly.

Proximity

Developing relationships with friends or romantic partners often happens by chance. This can be attributed, at least in part, to how close we are to those people. Proximity, or physical nearness, is among the most significant factors in building relationships. For instance, when young adults leave their family home, they tend to make friends with nearby classmates, roommates, and teammates. Proximity enables people to get to know each other and discover their similarities, which can lead to friendship or a romantic relationship. Proximity refers to not just geographical distance but also functional distance, which is the frequency with which we cross paths. For example, young adults who live in the same building tend to become closer and develop relationships because they see each other more frequently than people on different floors. How does proximity apply in the context of online relationships? Levine (2000) argues that in terms of developing online relationships and attraction, functional distance refers to being online simultaneously, such as in a chat room or an Internet forum, and crossing virtual paths.

Familiarity

Proximity plays a crucial role in attraction because it creates a sense of familiarity, often leading to increased attraction. Spending more time around someone or being exposed to them repeatedly can increase the chances of feeling attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe and comfortable with people we know well since we know what to expect from them. Dr. Zajonc (1968) labeled this as the mere exposure effect, which means that the more we are exposed to a stimulus like a person’s voice or presence, the more likely we are to view it positively.

Research indicates that we tend to like what is familiar to us, even if we are not aware of it consciously. This fundamental principle of attraction (Zajonc, 1980) means that young people with overbearing primary caregivers may be attracted to authoritative individuals, not because they enjoy being dominated but because they perceive such behavior as usual and familiar.

Similarity

Although some people may believe that opposite personalities can attract, research has shown that people prefer those similar. This similarity is significant in the context of marriage. Studies have suggested that couples are very similar in age, social status, race, education, physical appearance, values, and beliefs (McCann, 2016). This phenomenon is called the matching hypothesis (Mckillip & Redel, 1983). Essentially, we are attracted to individuals who share our perspectives and have similar attitudes toward life.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity plays a vital role in attraction. It means we tend to like people more if they like us back. In other words, it’s hard to form a bond with someone who doesn’t reciprocate our friendliness. Relationships are built on give-and-take, so the relationship is unlikely to work if one side is not reciprocating. We feel compelled to give back what we receive and maintain equilibrium in our relationships. This phenomenon has been observed by researchers across cultures (Gouldner, 1960).

Love

Most individuals will experience a romantic relationship in their lifetime. However, is love the same for everyone? Are there different types of love? Psychologist Robert Sternberg (2007) proposes that all kinds of love include three key elements: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Intimacy involves closeness, emotional support, and caring. Passion, on the other hand, entails both emotional and physiological arousal, such as sexual attraction and arousal. Finally, commitment refers to the decision to love and maintain that love over time. All types of close relationships, such as the love between a mother and child or the bond between friends, tend to include intimacy. However, passion is unique to romantic love.

Anthropologist Helen Fisher conducted a study using fMRI scans to observe brain activity in individuals who had recently fallen in love. Her research showed that the participants’ brain chemistry was similar to that of individuals with substance use disorders on a drug high (Cohen, 2007). Specifically, serotonin production increased by 40% in people who had just fallen in love. Additionally, these individuals displayed obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, the brain processes a breakup similarly to quitting a heroin habit (Fisher et al., 2010). Therefore, the physical pain and emotional distress experienced after a breakup are valid.

It’s also worth noting that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. Sexual desire starts in the striatum, a part of the brain that responds to pleasurable things like food, sex, and drugs. On the other hand, love requires conditioning and positive reinforcement to develop into a habit. Positive rewards, expectancies, and habits help love grow over time (Cacioppo, 2012).

Trends in Dating, Cohabitation, and Marriage

Singlehood

It is common for people in their early 20s to lead a lifestyle of being single in the United States. There has been a noticeable increase in adults opting to stay single. In 1960, only 1 in 10 adults aged 25 or older had never been married. However, in 2012, this number had increased to 1 in 5 (Wang & Parker, 2014). This trend is not limited to the United States alone but has been observed worldwide over the last 30 years. Being single has become a more acceptable way of life than in the past, and many people are content with their single status. However, whether or not someone is happy being single depends on their circumstances.

Reasons for Staying Single

There are many reasons why young adults choose to remain single. Some haven’t yet found the right partner, while others prefer to focus on their financial stability and career before settling down. Moreover, many young adults feel they are too young to get married and like waiting until they are prepared. It’s becoming increasingly common for adults to marry later in life, live together, or raise children outside of marriage. This shift in attitudes towards marriage may be due to young adults’ changing priorities, such as pursuing higher education and establishing their careers.

Dating

Technology and social media have diversified recently, making it easier for teens and young adults to connect.

Dating and the Internet

The Internet has revolutionized the way people find relationships. According to Finkel and colleagues (2007), social networking sites and the Internet perform three essential tasks. Firstly, they provide access to a database of individuals interested in meeting someone. Secondly, dating sites reduce proximity issues, allowing individuals to meet even if they are not geographically close. Thirdly, they provide a medium for communication between individuals. Some Internet dating websites advertise unique matching strategies based on personality, hobbies, and interests to identify the “perfect match” for people looking for love online. However, scientific questions about the effectiveness of Internet matching or online dating compared to face-to-face dating remain unanswered.

It is important to note that social networking sites have opened doors for many people to meet individuals they may not have had an opportunity to meet otherwise. Unfortunately, social networking sites can also be forums for unsuspecting people to be duped. Joost & Schulman’s (2010) documentary Catfish highlights how a man met a woman online and had an emotional relationship with her for months, only to discover later that the person he thought he was talking to did not exist. Therefore, individuals should be cautious when meeting others from online sources and research people’s backgrounds before meeting them in person.

Online communication is different from face-to-face interaction in several ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues to base their first impressions on, such as a person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings. In contrast, written messages are the only cues provided in computer-mediated meetings. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement may make it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. People tend to disclose more personal details about themselves more quickly when online, and a shy person may open up more without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. Additionally, someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships.

Hooking Up

United States demographic changes have significantly affected romantic relationships among emerging and early adults. As previously described, the age for puberty has declined, while the times for one’s first marriage and first child have increased. This results in a “historically unprecedented time gap where young adults are physiologically able to reproduce but not psychologically or socially ready to settle down and begin a family and child-rearing” (Garcia et al., 2012). Consequently, traditional forms of dating have shifted for some people to include more casual hookups that involve uncommitted sexual encounters (Bogle, 2008).

Emotional Consequences of Hooking Up

Concerns regarding hooking-up behavior are evident in the research literature. One significant finding is the high comorbidity of hooking up and substance use. Those engaging in non-monogamous sex are more likely to have used marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, and the overall risks of sexual activity are drastically increased with the addition of alcohol and drugs (Garcia et al., 2012). Regret has also been expressed, and those who had the most regret after hooking up also had more symptoms of depression (Welsh et al., 2006). Hookups were also found to be associated with lower self-esteem, increased guilt, and fostered feelings of using someone.

Hooking up can best be explained from a biological, psychological, and social perspective. Research indicates that some emerging adults feel it is necessary to engage in hooking-up behavior as part of the sexual script depicted in the culture and media. Additionally, they desire sexual gratification. However, many also want a more committed romantic relationship and may feel regret about uncommitted sex.

“Friends with Benefits”

Hookups are different than those relationships that involve continued mutual exchange. These relationships are often called “Friends with Benefits” (FWB) or “Booty Calls.” These relationships involve friends having casual sex without commitment. Hookups do not include a friendship relationship. Bisson and Levine (2009) found that 60% of 125 undergraduates reported a FWB relationship. The concern with FWB is that one partner may feel more romantically invested than the other (Garcia et al., 2012).

Cohabitation

Cohabitation is an arrangement where two or more people who are not married live together. These often involve a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a more long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increasingly common in Western countries during the past few decades due to changing social views regarding marriage, gender roles, employment, and religious and economic changes. With many jobs requiring advanced educational attainment, a competition between marriage and pursuing postsecondary education has ensued (Yu & Xie, 2015).

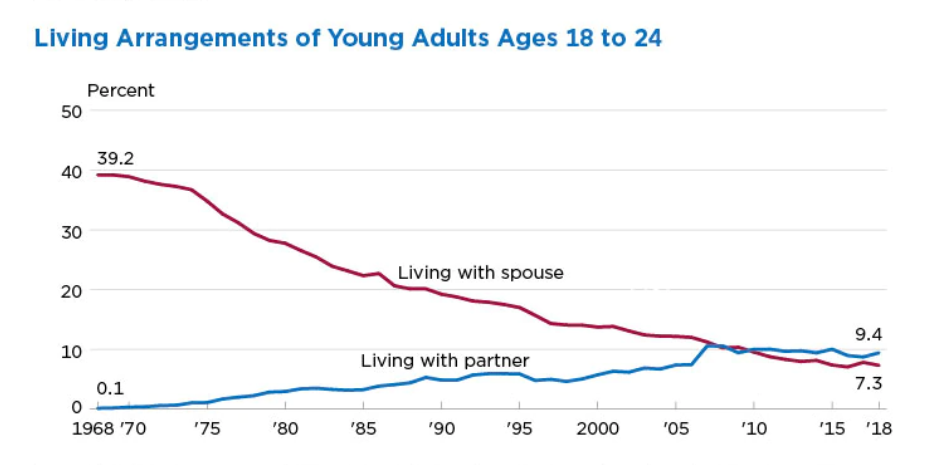

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2022), cohabitation has increased, while marriage has decreased in young adulthood. As seen in the graph below, over the past 50 years, 18-24-year-olds in the U.S. living with an unmarried partner have gone from 0.1 percent to 9.4 percent, while living with a spouse has gone from 39.2 percent to 7 percent. More 18-24-year-olds live with an unmarried partner now than a married one.

Similar increases in cohabitation have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. More children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. The Scandinavian countries have been the first to start this leading trend in Europe. However, many countries have since followed. Mediterranean Europe has traditionally been very conservative, with religion playing a substantial role.

Engagement and Marriage

Marriage Trends Worldwide: According to Cohen (2013), marriage has declined globally in recent decades. This decline has been observed in both rich and poor countries. The countries with the most significant drops in marriage were primarily wealthy countries such as France, Italy, Germany, Japan, and the United States. This decline is not only due to people delaying marriage but also due to high rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delayed or reduced marriage is associated with higher income and lower fertility rates worldwide.

Marriage Statistics in the United States: Wang and Taylor (2011) reported that in 1960, 72% of adults aged 18 or older were married. However, this number dropped to only 50% in 2010. Additionally, the age of first marriage has increased for both genders. In 1960, the average age for first marriage was 20 years for women and 23 years for men. In 2010, the average age had increased to 26.5 for women and almost 29 for men. Many reasons explain increases in singlehood and cohabitation, which can also account for the drop and delay in marriage.

Historical Perspective on Marriage and Elopement: In the past, marriage was a decision made by one’s family, not a personal choice. Arranged marriages ensured the proper transfer of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were a union of families rather than individuals. In the 18th century, the concept of personal choice in a marriage partner became more prevalent in Western Europe. Arranged marriages were considered “traditional,” and marriages based on love were “modern.” Many early “love” marriages were obtained by eloping (Thornton, 2005).

Elopement means secretly getting married.

In most countries worldwide, most people will marry in their lifetime. Around the world, people tend to get married later in life or not at all. For instance, people in more developed countries (e.g., Nordic and Western Europe) typically marry later in life—at an average age of 30 years. This is very different than, for example, the economically developing country of Afghanistan, which has one of the lowest average age statistics for marriage (United Nations, 2013).

Cultural Influences on Marriage

Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not entirely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not marry (Witt, 2010). For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their race, social class, age group, or religion. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group.

Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U.S. are homogamous concerning race, social class, age, and, to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages

In certain countries, it’s common for people to be matched and committed to marriage through arrangements made by their parents or professional marriage brokers.

In some cultures, it’s not unusual for the families of young individuals to find a suitable partner for them. In India, for instance, the marriage market refers to using marriage brokers or bureaus to link eligible singles together (Trivedi, 2013). To Westerners, the idea of arranged marriage may seem to take the romance out of the equation and go against personal freedom values. However, some argue that parents can make more mature decisions than young people.

While such involvement might seem inappropriate based on your upbringing, many individuals expect and appreciate such help. In India, for example, “parental arranged marriages are largely preferred to other forms of marital choices” (Ramsheena, 2015). Of course, one’s religious and social status plays a role in determining how involved a family may be.

Same-Sex Marriage and Couples Worldwide

As of 2022, over 30 countries have legalized same-sex marriage, and this number continues to grow. Additionally, many other countries have taken steps to recognize same-sex couples, such as by granting rights for domestic partnerships or common-law marriage status. On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that guaranteed same-sex marriage under the Constitution. This ruling declared that limiting marriage to heterosexual couples violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. It’s worth noting that this decision came 11 years after Massachusetts first legalized same-sex marriage. By the time of the Supreme Court ruling, 36 states and the District of Columbia had already followed suit (Masci et al., 2019).

What Are the Factors Associated with Education and Work in Early Adulthood?

Education in Early Adulthood

Over the last decade, there has been a growing concern about whether formal education is enough to prepare young adults for the workplace. It has become apparent that students need to learn what is often called “soft skills” in addition to the knowledge and skills specific to their chosen field of study. According to Pazich (2018), an education researcher, most American college students today are enrolling in business or other pre-professional programs. To be effective and successful workers and leaders, they not only need the content knowledge gained from liberal arts education but also communication, teamwork, and critical thinking skills. Considering that two-thirds of children who start primary school now will be employed in jobs that do not exist, it is impossible to learn every skill or fact they may need to know. However, they can learn how to learn, think, research, and communicate effectively to continually learn new things and adapt to changes in their careers and lives. Since the economy, technology, and global markets will continue to evolve, workers must have skills in listening, reading, writing, speaking, global awareness, critical thinking, civility, and computer literacy—all of which enhance success in the workplace.

Soft skills are non-technical skills that describe how you work and interact with others.

Career Choices in Early Adulthood

As we live longer and change jobs multiple times, it is essential to become lifelong learners. However, our initial career choice is still significant as many of us will change jobs within the same occupational field. Erikson’s theory suggests that our occupation mainly defines our identity.

Holland’s theory of career choice is well-known and proposes six personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional) and various work environments. The better the match between a person’s personality and the workplace characteristics, the more satisfied and successful they are likely to be in their career or vocational choice. Although research support has been mixed, we should note that personality traits alone cannot guarantee satisfaction and success in a career. Education, training, and abilities also need to align with the expectations and demands of the job. Besides, factors such as the state of the economy, availability of positions, and salary rates may also play practical roles in making choices about work.

Career Development and Employment

Work’s role is crucial in people’s lives, especially during emerging and early adulthood. This is when most people make choices that will help shape their careers. However, recent years have seen young adults frequently changing jobs and returning to school for further education and retraining. Despite this, researchers have found that occupational interests remain relatively stable. Thus, most people generally seek jobs with similar interests rather than entirely new careers (Rottinghaus, 2007).

Recent research suggests that Millennials want something different in their place of employment. According to a Gallup (2016) poll, Millennials want more than just a paycheck; they want a purpose. Unfortunately, only 29% of Millennials surveyed by Gallup reported being “engaged” at work. They report being less engaged than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers, with 55% of Millennials saying they are not engaged at all with their job. This indifference to their workplace may explain the greater tendency to switch careers. With their current job giving them little reason to stay, they are likelier to take any new opportunity to move on. Only half of Millennials saw themselves working at the same company a year later. Gallup estimates that this employment turnover and lack of engagement costs businesses $30.5 billion annually.

The economic downturn in recent years and Covid-19 have hit teens and young adults hard. Consequently, several young people have become NEETs, neither employed nor in education or training. While the number of young people who are NEETs has declined, there is concern that “without assistance, economically inactive young people won’t gain critical job skills and will never fully integrate into the wider economy or achieve their full earning potential” (Desilver, 2016). In Europe, where the rates of NEETs are persistently high, there is also concern that having such large numbers of young adults with little opportunity may increase the chances of social unrest.

To learn more about these early adulthood topics, but from a slightly different perspective—that of generations or cohorts—please visit the links below. “Millennials” are defined as individuals who were born between 1981 and 1996 and, as such, make up a large part of today’s young adults. “Gen Zers” are defined as those born after 1996.

Read This

Read more about GenZ, Millennials, and other Generations in the following articles:

- “Millennial life: How young adulthood today compares with prior generations,” from the Pew Research Center.

- “Gen Zers: what we know about Gen Z so far,” from the Pew Research Center.

So, What Have You Learned?

Emerging adults, typically between the ages of 18 and 25, are at the peak of their physical and sexual capacities. However, their tendency towards risk-taking behaviors leaves them vulnerable to various disorders such as accidents, alcohol and drug abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, intimate partner violence, and even suicide. Maintaining a healthy diet and an active lifestyle is crucial during this stage since it’s associated with health and certain illnesses in middle age. Their cognitive and brain development continues to be shaped and influenced by education and life experiences. Young adults may shift from formal logical thinking to postformal thinking, which enables them to consider multiple perspectives and contexts, appreciate ambiguity and uncertainty, and make practical decisions based on their experiences.

Further education plays an essential role in shaping the future for most young adults. Hence, we examined the correlation between education and work and discovered that exploring and choosing one’s career is crucial during this stage. Establishing intimate relationships with friends, family, and significant others is another important aspect of young adulthood. It involves love, dating, cohabitation, and marriage.

References

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family Relationships and Support Systems in Emerging Adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-008

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2003(100), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.75

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and nonsense. History of Psychology, 9(3), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.9.3.186

Arnett, J. J. & Schwab, J. (2012). The Clark University poll of emerging adults: Thriving, struggling, & hopeful. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development. Praeger.

Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (2009). Socio-emotional development: from infancy to young adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50(6), 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00787.x

Centers for Disease Control (2022). Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity causes and consequences. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription Opioids Overview. https://www.cdc.gov/rx-awareness/information/

CDC WONDER. Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Health Statistics. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1984). Origins and evolution of behavior disorders: From infancy to early adult life. Harvard University Press.

Cohen, E. (2007, February 15). Loving with all your … brain. http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/02/14/love.science/

Douglass, C. B. (Ed.). (2020). Barren states: The population “implosion” in Europe. Routledge.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton.

Facio, A., & Micocci, F. (2003). Emerging adulthood in Argentina. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2003(100), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.72

Fisher, H. E., Brown, L. L., Aron, A., Strong, G., & Mashek, D. (2010). Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00784.2009

Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000027

Goldscheider, F. K., & Goldscheider, C. (1999). The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. SAGE Publications.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love is conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Page 515

Henseler, C. (2017, September 6). Liberal arts is the foundation for professional success in the 21st century. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/liberal-arts-is-the-foundation-for-professional-success_b_5996d9a7e4b03b5e472cee9d#:~:text=From%20this%20view%2C%20graduates%20of,success%20in%20the%21st%20century.

Holland, A. S., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2012). Attachment styles in dating couples: Predicting relationship functioning over time. Personal Relationships, 19(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01350.x

Holland, J. (1984). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). The Guilford Press.

Levine, D. (2000). Virtual attraction: What rocks your boat. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 3(4), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493100420179

Lyman Stone. (2021). Number 4 in 2021: More Faith, Less Sex: Why Are So Many Unmarried Young Adults Not Having Sex? Institute for Family Studies. https://ifstudies.org/blog/number-4-in-2021-more-faith-less-sex-why-are-so-many-unmarried-young-adults-not-having-sex

Attribution

Tremika Cleary adapted this chapter from select chapters in Iowa State University Digital Press Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being, authored by Alisa Beyer, Julie Lazzara; Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Margaret Clark-Plaskie; Lumen Learning; Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Girl on tracks © Tremika Cleary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Fais_do_do_-_Feufollet_-_New_Orleans_JazzFest_2015 © Robbie Mendelson is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Perry’s scheme © Angie Balius is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Attachment in relationships © Angie Balius is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 4-category model w 2-dimensions of attachment adapted by Angie Balius is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 8-2 Loving couple © Kia Simmons is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- cohabitaiton-is-up-marriage-is-down-for-young-adults-figure-1 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 4332614299_3d26c37a0b_c © Vic Handa is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 8-4 © Bart Vis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license