19.4 Mammalian Heart and Blood Vessels

Mary Ann Clark; Jung Choi; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the structure of the heart and explain how cardiac muscle is different from other muscles

- Describe the cardiac cycle

- Explain the structure of arteries, veins, and capillaries, and how blood flows through the body

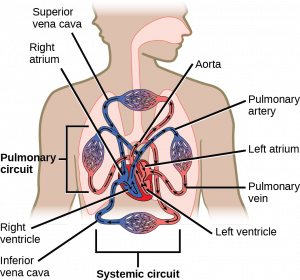

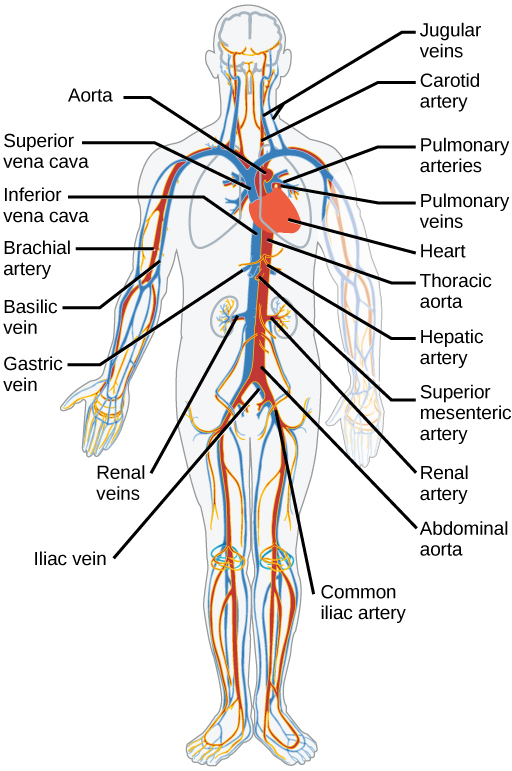

The heart is a complex muscle that pumps blood through the three divisions of the circulatory system: the coronary (vessels that serve the heart), pulmonary (heart and lungs), and systemic (systems of the body), as shown in the figure below. Coronary circulation intrinsic to the heart takes blood directly from the main artery (aorta) coming from the heart. For pulmonary and systemic circulation, the heart has to pump blood to the lungs or the rest of the body, respectively. In vertebrates, the lungs are relatively close to the heart in the thoracic cavity. The shorter distance to pump means that the muscle wall on the right side of the heart is not as thick as the left side which must have enough pressure to pump blood all the way to your big toe.

Visual Connection

The mammalian circulatory system is divided into three circuits: the systemic circuit, the pulmonary circuit, and the coronary circuit. Blood is pumped from veins of the systemic circuit into the right atrium of the heart, then into the right ventricle. Blood then enters the pulmonary circuit, and is oxygenated by the lungs. From the pulmonary circuit, blood reenters the heart through the left atrium. From the left ventricle, blood reenters the systemic circuit through the aorta and is distributed to the rest of the body. The coronary circuit, which provides blood to the heart, is not shown.

Structure of the Heart

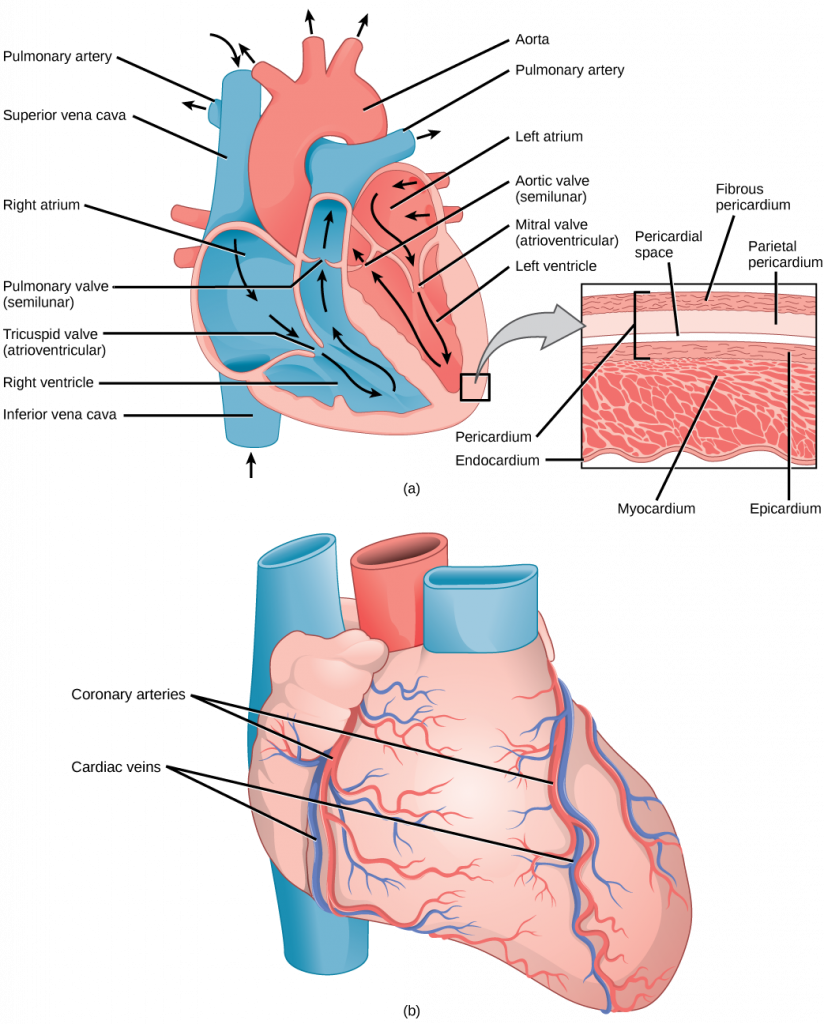

The heart muscle is asymmetrical as a result of the distance blood must travel in the pulmonary and systemic circuits. Since the right side of the heart sends blood to the pulmonary circuit, it is smaller than the left side, which must send blood out to the whole body in the systemic circuit, as shown in the figure below. In humans, the heart is about the size of a clenched fist; it is divided into four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. There is one atrium and one ventricle on the right side and one atrium and one ventricle on the left side. The atria are the chambers that receive blood, and the ventricles are the chambers that pump blood. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the superior vena cava, which drains blood from the jugular vein that comes from the brain and from the veins that come from the arms, as well as from the inferior vena cava, which drains blood from the veins that come from the lower organs and the legs. In addition, the right atrium receives blood from the coronary sinus, which drains deoxygenated blood from the heart itself. This deoxygenated blood then passes to the right ventricle through the atrioventricular valve or the tricuspid valve, a flap of connective tissue that opens in only one direction to prevent the backflow of blood. The valve separating the chambers on the left side of the heart valve is called the bicuspid or mitral valve. After it is filled, the right ventricle pumps the blood through the pulmonary arteries, bypassing the semilunar valve (or pulmonic valve) to the lungs for re-oxygenation. After blood passes through the pulmonary arteries, the right semilunar valves close preventing the blood from flowing backwards into the right ventricle. The left atrium then receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs via the pulmonary veins. This blood passes through the bicuspid valve or mitral valve (the atrioventricular valve on the left side of the heart) to the left ventricle where the blood is pumped out through the aorta, the major artery of the body, taking oxygenated blood to the organs and muscles of the body. Once blood is pumped out of the left ventricle and into the aorta, the aortic semilunar valve (or aortic valve) closes preventing blood from flowing backward into the left ventricle. This pattern of pumping is referred to as double circulation and is found in all mammals.

Visual Connection

The heart is composed of three layers: the epicardium, the myocardium, and the endocardium, illustrated in the figure above. The inner wall of the heart has a lining called the endocardium. The myocardium consists of the heart muscle cells that make up the middle layer and the bulk of the heart wall. The outer layer of cells is called the epicardium, of which the second layer is a membranous layered structure called the pericardium that surrounds and protects the heart; it allows enough room for vigorous pumping but also keeps the heart in place to reduce friction between the heart and other structures.

The heart has its own blood vessels that supply the heart muscle with blood. The coronary arteries branch from the aorta and surround the outer surface of the heart like a crown. They diverge into capillaries where the heart muscle is supplied with oxygen before converging again into the coronary veins to take the deoxygenated blood back to the right atrium where the blood will be re-oxygenated through the pulmonary circuit. The heart muscle will die without a steady supply of blood. Atherosclerosis is the blockage of an artery by the buildup of fatty plaques. Because of the size (narrow) of the coronary arteries and their function in serving the heart itself, atherosclerosis can be deadly in these arteries. The slowdown of blood flow and subsequent oxygen deprivation that results from atherosclerosis causes severe pain, known as angina, and complete blockage of the arteries will cause myocardial infarction: the death of cardiac muscle tissue, commonly known as a heart attack.

The Cardiac Cycle

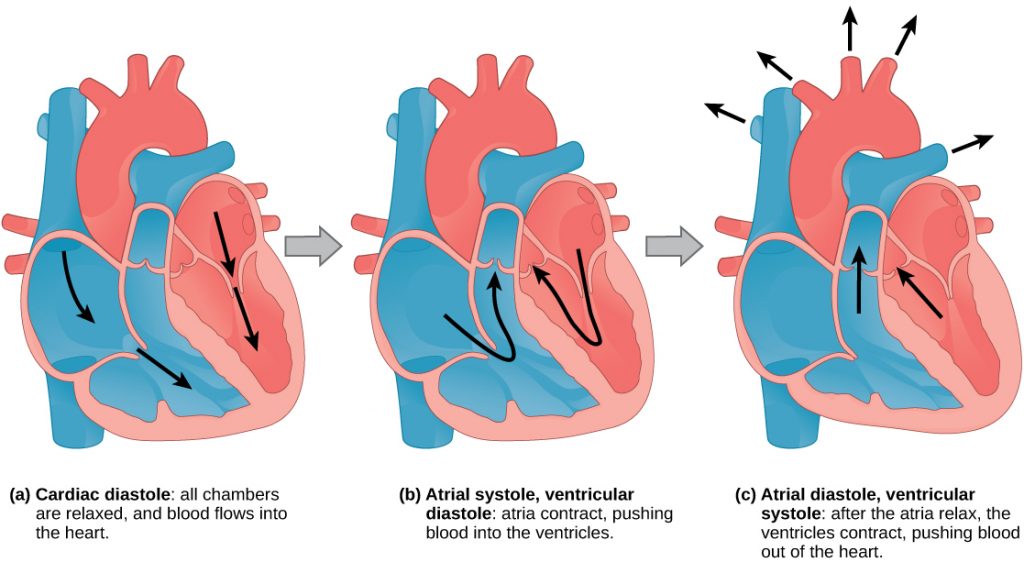

The main purpose of the heart is to pump blood through the body; it does so in a repeating sequence called the cardiac cycle. The cardiac cycle is the coordination of the filling and emptying of the heart of blood by electrical signals that cause the heart muscles to contract and relax. The human heart beats over 100,000 times per day. In each cardiac cycle, the heart contracts (systole), pushing out the blood and pumping it through the body; this is followed by a relaxation phase (diastole), where the heart fills with blood, as illustrated in the figure below. The atria contract at the same time, forcing blood through the atrioventricular valves into the ventricles. Closing of the atrioventricular valves produces a monosyllabic “lup” sound. Following a brief delay, the ventricles contract at the same time forcing blood through the semilunar valves into the aorta and the artery transporting blood to the lungs (via the pulmonary artery). Closing of the semilunar valves produces a monosyllabic “dup” sound.

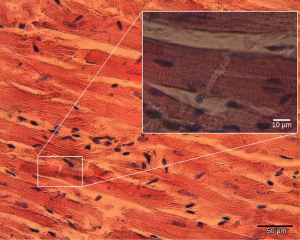

The pumping of the heart is a function of the cardiac muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, that make up the heart muscle. Cardiomyocytes, shown in the figure below, are distinctive muscle cells that are striated like skeletal muscle but pump rhythmically and involuntarily like smooth muscle; they are connected by intercalated disks exclusive to cardiac muscle. They are self-stimulated for a period of time, and isolated cardiomyocytes will beat if given the correct balance of nutrients and electrolytes.

The autonomous beating of cardiac muscle cells is regulated by the heart’s internal pacemaker that uses electrical signals to time the beating of the heart. The electrical signals and mechanical actions, illustrated in the figure below, are intimately intertwined. The internal pacemaker starts at the sinoatrial (SA) node, which is located near the wall of the right atrium. Electrical charges spontaneously pulse from the SA node causing the two atria to contract in unison. The pulse reaches a second node, called the atrioventricular (AV) node, between the right atrium and right ventricle where it pauses for approximately 0.1 second before spreading to the walls of the ventricles. From the AV node, the electrical impulse enters the bundle of His, then to the left and right bundle branches extending through the interventricular septum. Finally, the Purkinje fibers conduct the impulse from the apex of the heart up the ventricular myocardium, and then the ventricles contract. This pause allows the atria to empty completely into the ventricles before the ventricles pump out the blood. The electrical impulses in the heart produce electrical currents that flow through the body and can be measured on the skin using electrodes. This information can be observed as an electrocardiogram (ECG)—a recording of the electrical impulses of the cardiac muscle.

Link to Learning

Visit this site to see the heart’s “pacemaker” in action.

Arteries, Veins, and Capillaries

The blood from the heart is carried through the body by a complex network of blood vessels (see the figure below). Arteries take blood away from the heart. The main artery is the aorta that branches into major arteries that take blood to different limbs and organs. These major arteries include the carotid artery that takes blood to the brain, the brachial arteries that take blood to the arms, and the thoracic artery that takes blood to the thorax and then into the hepatic, renal, and gastric arteries for the liver, kidney, and stomach, respectively. The iliac artery takes blood to the lower limbs. The major arteries diverge into minor arteries, and then smaller vessels called arterioles, to reach more deeply into the muscles and organs of the body.

Arterioles diverge into capillary beds. Capillary beds contain a large number (10 to 100) of capillaries that branch among the cells and tissues of the body. Capillaries are narrow-diameter tubes that can fit red blood cells through in single file and are the sites for the exchange of nutrients, waste, and oxygen with tissues at the cellular level. Fluid also crosses into the interstitial space from the capillaries. The capillaries converge again into venules that connect to minor veins that finally connect to major veins that take blood high in carbon dioxide back to the heart. Veins are blood vessels that bring blood back to the heart. The major veins drain blood from the same organs and limbs that the major arteries supply. Fluid is also brought back to the heart via the lymphatic system.

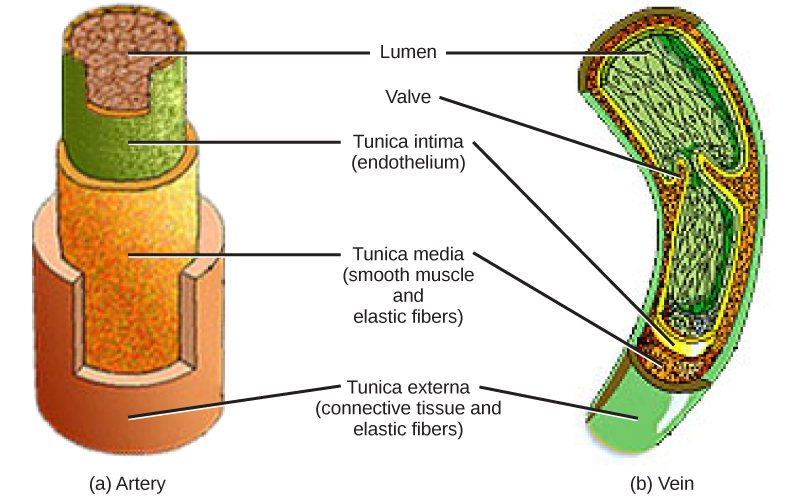

The structure of the different types of blood vessels reflects their function or layers. There are three distinct layers, or tunics, that form the walls of blood vessels (see the figure below). The first tunic is a smooth, inner lining of endothelial cells that are in contact with the red blood cells. The endothelial tunic is continuous with the endocardium of the heart. In capillaries, this single layer of cells is the location of diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the endothelial cells and red blood cells, as well as the exchange site via endocytosis and exocytosis. The movement of materials at the site of capillaries is regulated by vasoconstriction, narrowing of the blood vessels, and vasodilation, widening of the blood vessels; this is important in the overall regulation of blood pressure.

Veins and arteries both have two further tunics that surround the endothelium: the middle tunic is composed of smooth muscle and the outermost layer is connective tissue (collagen and elastic fibers). The elastic connective tissue stretches and supports the blood vessels, and the smooth muscle layer helps regulate blood flow by altering vascular resistance through vasoconstriction and vasodilation. The arteries have thicker smooth muscle and connective tissue than the veins to accommodate the higher pressure and speed of freshly pumped blood. The veins are thinner walled, as the pressure and rate of flow are much lower. In addition, veins are structurally different than arteries in that veins have valves to prevent the backflow of blood. Because veins have to work against gravity to get blood back to the heart, contraction of skeletal muscle assists with the flow of blood back to the heart.

Section Summary

The heart muscle pumps blood through three divisions of the circulatory system: coronary, pulmonary, and systemic. There is one atrium and one ventricle on the right side and one atrium and one ventricle on the left side. The pumping of the heart is a function of cardiomyocytes, distinctive muscle cells that are striated like skeletal muscle but pump rhythmically and involuntarily like smooth muscle. The internal pacemaker starts at the sinoatrial (SA) node, which is located near the wall of the right atrium. Electrical charges pulse from the SA node causing the two atria to contract in unison; then the pulse reaches the atrioventricular node between the right atrium and right ventricle. A pause in the electric signal allows the atria to empty completely into the ventricles before the ventricles pump out the blood. The blood from the heart is carried through the body by a complex network of blood vessels; arteries take blood away from the heart, and veins bring blood back to the heart.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Glossary

- angina

- pain caused by partial blockage of the coronary arteries by the buildup of plaque and lack of oxygen to the heart muscle

- aorta

- major artery of the body that takes blood away from the heart

- arteriole

- small vessel that connects an artery to a capillary bed

- artery

- blood vessel that takes blood away from the heart

- atherosclerosis

- buildup of fatty plaques in the coronary arteries in the heart

- atrioventricular valve

- one-way membranous flap of connective tissue between the atrium and the ventricle in the right side of the heart; also known as tricuspid valve

- bicuspid valve

- (also, mitral valve; left atrioventricular valve) one-way membranous flap between the atrium and the ventricle in the left side of the heart

- capillary

- smallest blood vessel that allows the passage of individual blood cells and the site of diffusion of oxygen and nutrient exchange

- capillary bed

- large number of capillaries that converge to take blood to a particular organ or tissue

- cardiac cycle

- filling and emptying the heart of blood by electrical signals that cause the heart muscles to contract and relax

- cardiomyocyte

- specialized heart muscle cell that is striated but contracts involuntarily like smooth muscle

- coronary artery

- vessel that supplies the heart tissue with blood

- coronary vein

- vessel that takes blood away from the heart tissue back to the chambers in the heart

- diastole

- relaxation phase of the cardiac cycle when the heart is relaxed and the ventricles are filling with blood

- electrocardiogram (ECG)

- recording of the electrical impulses of the cardiac muscle

- endocardium

- innermost layer of tissue in the heart

- epicardium

- outermost tissue layer of the heart

- inferior vena cava

- drains blood from the veins that come from the lower organs and the legs

- myocardial infarction

- (also, heart attack) complete blockage of the coronary arteries and death of the cardiac muscle tissue

- myocardium

- heart muscle cells that make up the middle layer and the bulk of the heart wall

- pericardium

- membrane layer protecting the heart; also part of the epicardium

- semilunar valve

- membranous flap of connective tissue between the aorta and a ventricle of the heart (the aortic or pulmonary semilunar valves)

- sinoatrial (SA) node

- the heart’s internal pacemaker; located near the wall of the right atrium

- superior vena cava

- drains blood from the jugular vein that comes from the brain and from the veins that come from the arms

- systole

- contraction phase of cardiac cycle when the ventricles are pumping blood into the arteries

- tricuspid valve

- one-way membranous flap of connective tissue between the atrium and the ventricle in the right side of the heart; also known as atrioventricular valve

- vasoconstriction

- narrowing of a blood vessel

- vasodilation

- widening of a blood vessel

- vein

- blood vessel that brings blood back to the heart

- vena cava

- major vein of the body returning blood from the upper and lower parts of the body; see the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava

- venule

- blood vessel that connects a capillary bed to a vein