26.5 Preserving Biodiversity

Jung Choi; Mary Ann Clark; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Identify new technologies and methods for describing biodiversity

- Explain the legislative framework for conservation

- Describe principles and challenges of conservation preserve design

- Identify examples of the effects of habitat restoration

- Discuss the role of zoos in biodiversity conservation

Preserving biodiversity is an extraordinary challenge that must be met by greater understanding of biodiversity itself, changes in human behavior and beliefs, and various preservation strategies.

Measuring Biodiversity

The technology of molecular genetics and data processing and storage is maturing to the point where cataloging the planet’s species in an accessible way is now feasible. DNA barcoding is one molecular genetic method, which takes advantage of rapid evolution in a mitochondrial gene (cytochrome c oxidase 1) present in eukaryotes, except for plants, to identify species using the sequence of portions of the gene. However, plants may be barcoded using a combination of chloroplast genes. Rapid mass sequencing machines make the molecular genetics portion of the work relatively inexpensive and quick. Computer resources store and make available large volumes of data. Projects are currently underway to use DNA barcoding to catalog museum specimens, which have already been named and studied, as well as testing the method on less-studied groups. As of mid-2017, close to 200,000 named species had been barcoded. Early studies suggest there are significant numbers of undescribed species that looked too much like sibling species to previously be recognized as different. These now can be identified with DNA barcoding.

Numerous computer databases now provide information about named species and a framework for adding new species. However, as already noted, at the present rate of description of new species, it will take close to 500 years before the complete catalog of life is known. Many, perhaps most, species on the planet do not have that much time.

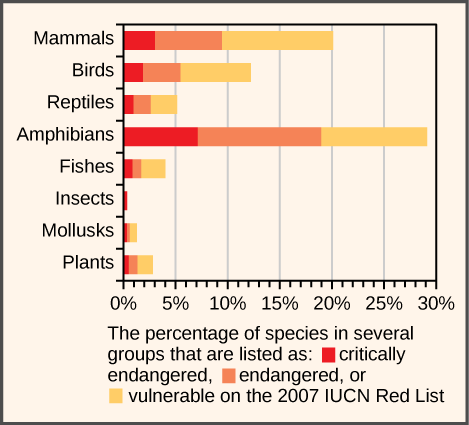

There is also the problem of understanding which species known to science are threatened and to what degree they are threatened. This task is carried out by the non-profit IUCN which, as previously mentioned, maintains the Red List—an online listing of endangered species categorized by taxonomy, type of threat, and other criteria. The Red List is supported by scientific research. In 2011, the list contained 61,000 species, all with supporting documentation.

Visual Connection

Changing Human Behavior

Legislation throughout the world has been enacted to protect species. The legislation includes international treaties as well as national and state laws. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) treaty came into force in 1975. The treaty, and the national legislation that supports it, provides a legal framework for preventing approximately 33,000 listed species from being transported across nations’ borders, thus protecting them from being caught or killed when international trade is involved. The treaty is limited in its reach because it only deals with international movement of organisms or their parts. It is also limited by various countries’ ability or willingness to enforce the treaty and supporting legislation. The illegal trade in organisms and their parts is probably a market in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Illegal wildlife trade is monitored by another non-profit: Trade Records Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce (TRAFFIC).

Within many countries there are laws that protect endangered species and regulate hunting and fishing. In the United States, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was enacted in 1973. Species at risk are listed by the Act; the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is required by law to develop plans that protect the listed species and bring them back to sustainable numbers. The Act, and others like it in other countries, is a useful tool, but it suffers because it is often difficult to get a species listed, or to get an effective management plan in place once it is listed. Additionally, species may be controversially taken off the list without necessarily having had a change in their situation. More fundamentally, the approach to protecting individual species rather than entire ecosystems is both inefficient and focuses efforts on a few highly visible and often charismatic species, perhaps at the expense of other species that go unprotected. At the same time, the Act has a critical habitat provision outlined in the recovery mechanism that may benefit species other than the one targeted for management.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) is an agreement between the United States and Canada that was signed into law in 1918 in response to declines in North American bird species caused by hunting. The Act now lists over 800 protected species. It makes it illegal to disturb or kill the protected species or distribute their parts (much of the hunting of birds in the past was for their feathers).

As already mentioned, the private non-profit sector plays a large role in the conservation effort both in North America and around the world. The approaches range from species-specific organizations to the broadly focused IUCN and TRAFFIC. The Nature Conservancy takes a novel approach. It purchases land and protects it in an attempt to set up preserves for ecosystems.

Although it is focused largely on reducing carbon and related emissions, the Paris Climate Agreement is a significant step toward altering human behavior in a way that should affect biodiversity. If the agreement is successful in its goal of halting global temperature rise, many species negatively affected by climate change may benefit. Assessments of the accord’s implementation will not take place until 2023, and measurement of its effects will not be feasible for some time. However, the agreement, signed by over 194 countries, represents the world’s most concerted and unified effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, embrace alternative energy sources, and ease climate pressure on ecosystems.

Conservation in Preserves

The establishment of wildlife and ecosystem preserves is one of the key tools in conservation efforts. A preserve is an area of land set aside with varying degrees of protection for the organisms that exist within the boundaries of the preserve. Preserves can be effective in the short term for protecting both species and ecosystems, but they face challenges that scientists are still exploring to strengthen their viability as long-term solutions to the preservation of biodiversity and the prevention of extinction.

How Much Area to Preserve?

Due to the way protected lands are allocated and the way biodiversity is distributed, it is challenging to determine how much land or marine habitat should be protected. The IUCN World Parks Congress estimated that 11.5 percent of Earth’s land surface was covered by preserves of various kinds in 2003. We should note that this area is greater than previous goals; however, it only includes 9 out of 14 recognized major biomes. Similarly, individual animals or types of animals are not equally represented on preserves. For example, high-quality preserves include only about 50 percent of threatened amphibian species. To guarantee that all threatened species will be properly protected, either the protected areas must increase in size, or the percentage of high-quality preserves must increase, or preserves must be targeted with greater attention to biodiversity protection. Researchers indicate that more attention to the latter solution is required.

Preserve Design

There has been extensive research into optimal preserve designs for maintaining biodiversity. The fundamental principle behind much of the research has been the seminal theoretical work of Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson published in 1967 on island biogeography.[1] This work sought to understand the factors affecting biodiversity on islands. The fundamental conclusion was that biodiversity on an island was a function of the origin of species through migration, speciation, and extinction on that island. Islands farther from a mainland are harder to get to, so migration is lower and the equilibrium number of species is lower. Within island populations, evidence suggests that the number of species gradually increases to a level similar to the numbers on the mainland from which the species is suspected to have migrated. In addition, smaller islands are harder to find, so their immigration rates for new species are typically lower. Smaller islands are also less geographically diverse so all things being equal, there are fewer niches to promote speciation. And finally, smaller islands support smaller populations, so the probability of extinction is higher.

As islands get larger, the number of species able to colonize the island and find suitable niches on the island increases, although the effect of island area on species numbers is not a direct correlation. Conservation preserves can be seen as “islands” of habitat within “an ocean” of non-habitat. For a species to persist in a preserve, the preserve must be large enough to support it. The critical size depends, in part, on the home range that is characteristic of the species. A preserve for wolves, which range hundreds of kilometers, must be much larger than a preserve for butterflies, which might range within ten kilometers during its lifetime. But larger preserves have more core area of optimal habitat for individual species, they have more niches to support more species, and they attract more species because they can be found and reached more easily.

Preserves perform better when there are buffer zones around them of suboptimal habitat. The buffer allows organisms to exit the boundaries of the preserve without immediate negative consequences from predation or lack of resources. One large preserve is better than the same area of several smaller preserves because there is more core habitat unaffected by edges. For this same reason, preserves in the shape of a square or circle will be better than a preserve with many thin “arms.” If preserves must be smaller, then providing wildlife corridors between them so that individuals (and their genes) can move between the preserves, for example along rivers and streams, will make the smaller preserves behave more like a large one. All of these factors are taken into consideration when planning the nature of a preserve before the land is set aside.

In addition to the physical, biological, and ecological specifications of a preserve, there are a variety of policy, legislative, and enforcement specifications related to uses of the preserve for functions other than protection of species. These can include anything from timber extraction, mineral extraction, regulated hunting, human habitation, and nondestructive human recreation. Many of these policy decisions are made based on political pressures rather than conservation considerations. In some cases, wildlife protection policies have been so strict that subsistence-living indigenous populations have been forced from ancestral lands that fell within a preserve. In other cases, even if a preserve is designed to protect wildlife, if the protections are not or cannot be enforced, the preserve status will have little meaning in the face of illegal poaching and timber extraction. This is a widespread problem with preserves in areas of the tropics.

Limitations on Preserves

Some of the limitations of preserves as conservation tools are evident from the discussion of preserve design. Political and economic pressures typically make preserves smaller, rather than larger, so setting aside areas that are large enough is difficult. If the area set aside is sufficiently large, there may not be sufficient area to create a buffer around the preserve. In this case, an area on the outer edges of the preserve inevitably becomes a riskier suboptimal habitat for the species in the preserve. Enforcement of protections is also a significant issue in countries without the resources or political will to prevent poaching and illegal resource extraction.

Climate change will create inevitable problems with the location of preserves. The species within them may migrate to higher latitudes as the habitat of the preserve becomes less favorable. Scientists are planning for the effects of global warming on future preserves and striving to predict the need for new preserves to accommodate anticipated changes to habitats; however, the end effectiveness is tenuous since these efforts are prediction based.

Finally, an argument can be made that conservation preserves indicate that humans are growing more separate from nature and that humans only operate in ways that do damage to biodiversity. Creating preserves may reduce the pressure on humans outside the preserve to be sustainable and non-damaging to biodiversity. On the other hand, properly managed, high-quality preserves present opportunities for humans to witness nature in a less damaging way, and preserves may present some financial benefits to local economies. Ultimately, the economic and demographic pressures on biodiversity are unlikely to be mitigated by preserves alone. In order to fully benefit from biodiversity, humans will need to alter activities that damage it.

Link to Learning

Habitat Restoration

Habitat restoration holds considerable promise as a mechanism for restoring and maintaining biodiversity. Of course, once a species has become extinct, its restoration is impossible. However, restoration can improve the biodiversity of degraded ecosystems. Reintroducing wolves, a top predator, to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 led to dramatic changes in the ecosystem that increased biodiversity. The wolves function to suppress elk and coyote populations and provide more abundant resources to the guild of carrion eaters. Reducing elk populations has allowed revegetation of riparian areas, which has increased the diversity of species in that habitat. Decreasing the coyote population has increased the populations of species that were previously suppressed by this predator. The number of species of carrion eaters has increased because of the predatory activities of the wolves. In this habitat, the wolf is a keystone species, meaning a species that is instrumental in maintaining diversity in an ecosystem. Removing a keystone species from an ecological community may cause a collapse in diversity. The results from the Yellowstone experiment suggest that restoring a keystone species can have the effect of restoring biodiversity in the community (see figure below). Ecologists have argued for the identification of keystone species where possible and for focusing protection efforts on those species; likewise, it also makes sense to attempt to return them to their ecosystem if they have been removed.

![[alt] Photo A shows a pack of wolves walking on snow. Photo B shows a river running through a meadow with a few copses of trees, some living and some dead. Photo C shows and elk, and photo d shows a beaver.](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/27/2022/03/Figure_47_04_02abcd.jpg)

Other large-scale restoration experiments underway involve dam removal, which is a national movement that is accelerating in importance. In the United States, since the mid-1980s, many aging dams have been considered for removal rather than replacement because of shifting beliefs about the ecological value of free-flowing rivers and because many dams no longer provide the benefits and functions that they did when they were first built. The measured benefits of dam removal include restoration of naturally fluctuating water levels (the purpose of dams is frequently to reduce variation in river flows), which leads to increased fish diversity and improved water quality. In the Pacific Northwest, dam removal projects are expected to increase populations of salmon, which is considered a keystone species because it transports key nutrients to inland ecosystems during its annual spawning migrations. In other regions such as the Atlantic coast, dam removal has allowed the return of spawning anadromous fish species (species that are born in fresh water, live most of their lives in salt water, and return to fresh water to spawn). Some of the largest dam removal projects have yet to occur or have happened too recently for the consequences to be measured. The large-scale ecological experiments that these removal projects constitute will provide valuable data for other dam projects slated either for removal or construction.

The Role of Captive Breeding

Zoos have sought to play a role in conservation efforts both through captive breeding programs and education. The transformation of the missions of zoos from collection and exhibition facilities to organizations that are dedicated to conservation is ongoing and gaining strength. In general, it has been recognized that, except in some specifically targeted cases, captive breeding programs for endangered species are inefficient and often prone to failure when the species are reintroduced to the wild. However, captive breeding programs have yielded some success stories, such as the American condor reintroduction to the Grand Canyon and the reestablishment of the Whooping Crane along the Midwest flyway.

Unfortunately, zoo facilities are far too limited to contemplate captive breeding programs for the number of species that are now at risk. Education is another potential positive impact of zoos on conservation efforts, particularly given the global trend toward urbanization and the consequent reduction in contact between people and wildlife. A number of studies have been performed to look at the effectiveness of zoos on people’s attitudes and actions regarding conservation; at present, the results tend to be mixed.

Section Summary

New technological methods such as DNA barcoding and information processing and accessibility are facilitating the cataloging of the planet’s biodiversity. There is also a legislative framework for biodiversity protection. International treaties such as CITES regulate the transportation of endangered species across international borders. Legislation within individual countries protecting species and agreements on global warming have had limited success; the Paris Climate Accord is currently being implemented as a means to reduce global climate change.

In the United States, the Endangered Species Act protects listed species but is hampered by procedural difficulties and a focus on individual species. The Migratory Bird Act is an agreement between Canada and the United States to protect migratory birds. The non-profit sector is also very active in conservation efforts in a variety of ways.

Conservation preserves are a major tool in biodiversity protection. Presently, 11 percent of Earth’s land surface is protected in some way. The science of island biogeography has informed the optimal design of preserves; however, preserves have limitations imposed by political and economic forces. In addition, climate change will limit the effectiveness of preserves in the future. A downside of preserves is that they may lessen the pressure on human societies to function more sustainably outside the preserves.

Habitat restoration has the potential to restore ecosystems to previous biodiversity levels before species become extinct. Examples of restoration include reintroduction of keystone species and removal of dams on rivers. Zoos have attempted to take a more active role in conservation and can have a limited role in captive breeding programs. Zoos also have a useful role in education.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Glossary

- DNA barcoding

- molecular genetic method for identifying a unique genetic sequence to associate with a species

Footnotes

- Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson, E. O., The Theory of Island Biogeography (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967). ↵