14 Demography and Population

Fracking, another word for hydraulic fracturing, is a method used to recover gas and oil from shale by drilling down into the earth and directing a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and proprietary chemicals into the rock. Commonly, this process also includes drilling horizontally into the rock to create new pathways for gas to travel. While energy companies view fracking as a profitable revolution in the industry, there are a number of concerns associated with the practice. Fracking has brought temporary economic growth, since 2008, to rural communities while simultaneously creating environmental and human health concerns (Murphy, 2020). Fracking has gathered momentum lately and has become a subject of political debate and controversy (Mazur, 2016)

First, fracking requires huge amounts of water. Water transportation comes at a high environmental cost, and once mixed with fracking chemicals, water is unsuitable for human and animal consumption, though it is estimated that between 10 percent and 90 percent of the contaminated water is returned to the water cycle. Second, the chemicals used in a fracking mix are potentially carcinogenic. These chemicals may pollute groundwater near the extraction site (Colborn, Kwiatkowski, Schultz, and Bachran 2011; United States 2011). Industry leaders suggest that such contamination is unlikely and that when it does occur, it is incidental and related to unavoidable human error rather than the expected risk of the practice, but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s study of fracking is ongoing (Environmental Protection Agency 2014). The third concern is that fracking may cause minor earthquakes by undermining the seismic stability of an area—a concern downplayed by the companies involved (Henry 2012). Finally, gas is not a renewable source of energy; this is a negative in the eyes of those who oppose continued reliance on fossil fuels.

Fracking is not without its advantages. Its supporters offer statistics that suggest it reduces unemployment and contributes to economic growth (IHS Global Insights 2012). Since it allows energy companies access to previously nonviable and completely untapped oil and gas reserves, fracking boosts domestic oil production and lowers energy costs (IHS Global Insights 2012). Finally, fracking expands the production of low-emission industrial energy.

As you read this chapter, consider how an increasing global population can balance environmental concerns with opportunities for industrial and economic growth. Think about how much water pollution can be justified by the need to lower U.S. dependence on foreign energy supplies. Are the potential employment and economic growth associated with fracking worth some environmental degradation?

As the discussion of fracking illustrates, there are important societal issues connected to the environment and how and where people live. Sociologists begin to examine these issues through demography, or the study of population and how it relates to urbanization, and the study of the social, political, and economic relationships in cities. Environmental sociologists look at the study of how humans interact with their environments. Today, as has been the case many times in history, we are at a point of conflict in a number of these areas. The world’s population reached seven billion between 2011 and 2012. When will it reach eight billion? Can our planet sustain such a population? We generate more trash than ever, from Starbucks cups to obsolete cell phones containing toxic chemicals to food waste that could be composted. You may be unaware of where your trash ends up. And while this problem exists worldwide, trash issues are often more acute in urban areas. Cities and city living create new challenges for both society and the environment that make interactions between people and places of critical importance.

How do sociologists study population and urbanization issues? Functionalist sociologists might focus on the way all aspects of population, urbanization, and the environment serve as vital and cohesive elements, ensuring the continuing stability of society. They might study how the growth of the global population encourages emigration and immigration, and how emigration and immigration services strengthen ties between nations. Or they might research the way migration affects environmental issues; for example, how have forced migrations, and the resulting changes in a region’s ability to support a new group, affected both the displaced people and the area of relocation? Another topic functionalists might research is the way various urban neighborhoods specialize to serve cultural and financial needs.

A conflict theorist, interested in the creation and reproduction of inequality, might ask how peripheral nations’ lack of family planning affects their overall population in comparison to core nations that tend to have lower fertility rates. Or, how do inner cities become ghettos, nearly devoid of jobs, education, and other opportunities? A conflict theorist might also study environmental racism and other forms of environmental inequality. For example, which parts of New Orleans society were the most responsive to the evacuation order during Hurricane Katrina? Which area was most affected by the flooding? And where (and in what conditions) were people from those areas housed, both during and before the evacuation?

A symbolic interactionist interested in the day-to-day interaction of groups and individuals might research topics like the way family-planning information is presented to and understood by different population groups, the way people experience and understand urban life, and the language people use to convince others of the presence (or absence) of global climate change. For example, some politicians wish to present the study of global warming as junk science, and other politicians insist it is a proven fact.

14.1 Demography and Population

Learning Objectives

- Understand demographic measurements like fertility and mortality rates

- Describe a variety of demographic theories, such as Malthusian, cornucopian, zero population growth, and demographic transition theories

- Be familiar with current population trends and patterns

- Understand the difference between an internally displaced person, an asylum-seeker, and a refugee

Between 2011 and 2012, we reached a population milestone of 7 billion humans on the earth’s surface. According to the World Population Prospects 2019, the World population is projected at 7,874,965,825 or 7,875 million or 7.87 billion as of July 1, 2021. Accordingly, In 2023, the human population will grow to more than 8 billion, and by 2037, this number will exceed 9 billion. The rapidity with which this is happening demonstrates an exponential increase from the time it took to grow from 5 billion to 6 billion people. In short, the planet is filling up. How quickly will we go from 7 billion to 8 billion? How will that population be distributed? Where is the population the highest? Where is it slowing down? Where will people live? To explore these questions, we turn to demography or the study of populations. Three of the most important components that affect the issues above are fertility, mortality, and migration.

The fertility rate of a society is a measure noting the number of children born. The fertility number is generally lower than the fecundity number, which measures the potential number of children that could be born to women of childbearing age. Sociologists measure fertility using the crude birthrate (the number of live births per 1,000 people per year). Just as fertility measures childbearing, the mortality rate is a measure of the number of people who die. A crude death rate is a number derived from the number of deaths per 1,000 people per year. When analyzed together, fertility and mortality rates help researchers understand the overall growth occurring in a population.

Another key element in studying populations is the movement of people into and out of an area. Migration may take the form of immigration, which describes movement into an area to take up permanent residence, or emigration, which refers to movement out of an area to another place of permanent residence. Migration might be voluntary (as when college students study abroad), involuntary (as when Syrians evacuated war-torn areas), or forced (as when many Native American tribes were removed from the lands they’d lived in for generations).

Big Picture

The 2014 Child Migration Crisis

Children have always contributed to the total number of migrants crossing the southern border of the United States illegally, but in 2014, a steady overall increase in unaccompanied minors from Central America reached crisis proportions when tens of thousands of children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras crossed the Rio Grande and overwhelmed border patrols and local infrastructure (Dart 2014).

Since legislators passed the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 in the last days of the Bush administration, unaccompanied minors from countries that do not share a border with the United States are guaranteed a hearing with an immigration judge where they may request asylum based on a “credible” fear of persecution or torture (U.S. Congress 2008). In some cases, these children are looking for relatives and can be placed with family while awaiting a hearing on their immigration status; in other cases, they are held in processing centers until the Department of Health and Human Services makes other arrangements (Popescu 2014).

The 2014 surge placed such a strain on state resources that Texas began transferring the children to Immigration and Naturalization facilities in California and elsewhere, without incident for the most part. On July 1, 2014, however, buses carrying the migrant children were blocked by protesters in Murrietta, California, who chanted, “Go home” and “We don’t want you.” (Fox News and Associated Press 2014; Reyes 2014).

Given the fact that these children are fleeing various kinds of violence and extreme poverty, how should the U.S. government respond? Should the government pass laws granting a general amnesty? Or should it follow a zero-tolerance policy, automatically returning any and all unaccompanied minor migrants to their countries of origin so as to discourage additional immigration that will stress the already overwhelmed system?

A functional perspective theorist might focus on the dysfunctions caused by the sudden influx of underage asylum seekers, while a conflict perspective theorist might look at the way social stratification influences how the members of a developed country treat the lower-status migrants from less-developed countries in Latin America. An interactionist theorist might see significance in the attitude of the Murrietta protesters toward the migrant children. Which theoretical perspective makes the most sense to you?

Population Growth

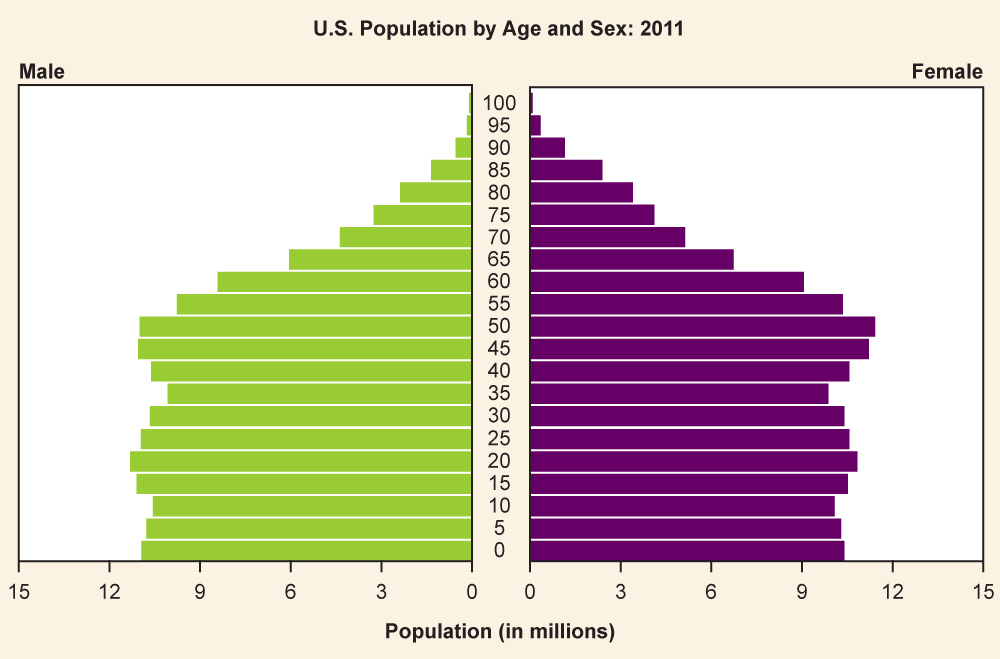

Changing fertility, mortality, and migration rates make up the total population composition, a snapshot of the demographic profile of a population. This number can be measured for societies, nations, world regions, or other groups. The population composition includes the sex ratio, the number of men for every hundred women, as well as the population pyramid, a picture of population distribution by sex and age (Figure 14.4).

| Country | Population (in millions) | Fertility Rate (number of children per adult woman) | Mortality Rate (per 1,000 births) | Sex Ratio Male to Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 31.8 | 5.4 | 14.1 | 1.03 |

| Sweden | 9.7 | 1.9 | 9.6 | 0.98 |

| United States of America | 318.92 | 2.0 | 8.2 | 0.97 |

Comparing the three countries in Table 14.1 reveals that there are more men than women in Afghanistan, whereas the reverse is true in Sweden and the United States. Afghanistan also has significantly higher fertility and mortality rates than either of the other two countries. Do these statistics surprise you? How do you think the population makeup affects the political climate and economics of the different countries?

Demographic Theories

Sociologists have long looked at population issues as central to understanding human interactions. Below we will look at four theories about the population that inform sociological thought: Malthusian, zero population growth, cornucopian, and demographic transition theories.

Malthusian Theory

Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) was an English clergyman who made dire predictions about the earth’s ability to sustain its growing population. According to Malthusian theory, three factors would control the human population that exceeded the earth’s carrying capacity, or how many people can live in a given area considering the number of available resources. Malthus identified these factors as war, famine, and disease (Malthus 1798). He termed them “positive checks” because they increase mortality rates, thus keeping the population in check. They are countered by “preventive checks,” which also control the population by reducing fertility rates; preventive checks include birth control and celibacy. Thinking practically, Malthus saw that people could produce only so much food in a given year, yet the population was increasing at an exponential rate. Eventually, he thought, people would run out of food and begin to starve. They would go to war over increasingly scarce resources and reduce the population to a manageable level, and then the cycle would begin anew.

Of course, this has not exactly happened. The human population has continued to grow long past Malthus’s predictions. So what happened? Why didn’t we die off? There are three reasons sociologists believe we are continuing to expand the population of our planet. First, technological increases in food production have increased both the amount and quality of calories we can produce per person. Second, human ingenuity has developed new medicine to curtail death from disease. Finally, the development and widespread use of contraception and other forms of family planning have decreased the speed at which our population increases. But what about the future? Some still believe Malthus was correct and that ample resources to support the earth’s population will soon run out.

Zero Population Growth

A neo-Malthusian researcher named Paul Ehrlich brought Malthus’s predictions into the twentieth century. However, according to Ehrlich, it is the environment, not specifically the food supply, that will play a crucial role in the continued health of the planet’s population (Ehrlich 1968). Ehrlich’s ideas suggest that the human population is moving rapidly toward complete environmental collapse, as privileged people use up or pollute a number of environmental resources such as water and air. He advocated for a goal of zero population growth (ZPG), in which the number of people entering a population through birth or immigration is equal to the number of people leaving it via death or emigration. While support for this concept is mixed, it is still considered a possible solution to global overpopulation.

Cornucopian Theory

Of course, some theories are less focused on the pessimistic hypothesis that the world’s population will meet a detrimental challenge to sustaining itself. Cornucopian theory scoffs at the idea of humans wiping themselves out; it asserts that human ingenuity can resolve any environmental or social issues that develop. As an example, it points to the issue of food supply. If we need more food, the theory contends, agricultural scientists will figure out how to grow it, as they have already been doing for centuries. After all, in this perspective, human ingenuity has been up to the task for thousands of years and there is no reason for that pattern not to continue (Simon 1981).

Demographic Transition Theory

Whether you believe that we are headed for environmental disaster and the end of human existence as we know it, or you think people will always adapt to changing circumstances, we can see clear patterns in population growth. Societies develop along a predictable continuum as they evolve from unindustrialized to postindustrial. Demographic transition theory (Caldwell and Caldwell 2006) suggests that future population growth will develop along with a predictable four-stage model.

In Stage 1, birth, death, and infant mortality rates are all high, while life expectancy is short. An example of this stage is the 1800s in the United States. As countries begin to industrialize, they enter Stage 2, where birth rates are higher while infant mortality and death rates drop. Life expectancy also increases. Afghanistan is currently in this stage. Stage 3 occurs once a society is thoroughly industrialized; birth rates decline, while life expectancy continues to increase. Death rates continue to decrease. Mexico’s population is at this stage. In the final phase, Stage 4, we see the postindustrial era of society. Birth and death rates are low, people are healthier and live longer, and society enters a phase of population stability. The overall population may even decline. For example, Sweden is considered to be in Stage 4.

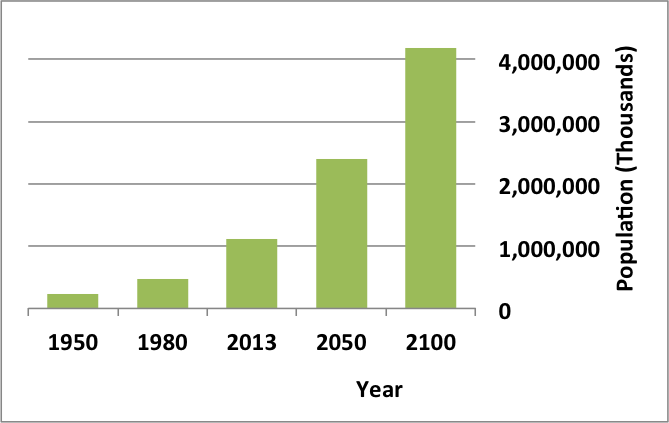

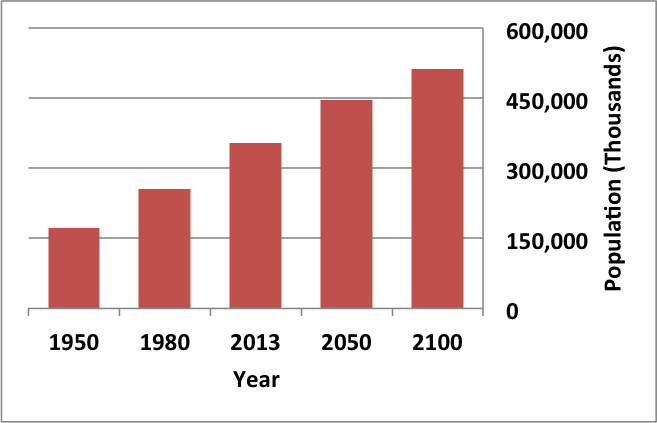

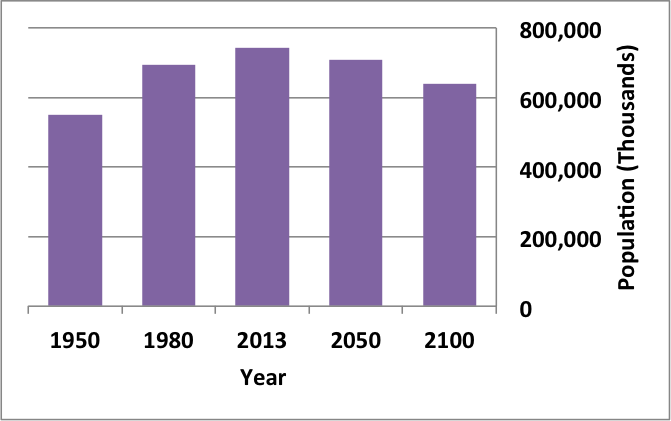

The United Nations Population Fund (2008) categorizes nations as high fertility, intermediate fertility, or low fertility. The United Nations (UN) anticipates the population growth will triple between 2011 and 2100 in high-fertility countries, which are currently concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. For countries with intermediate fertility rates (the United States, India, and Mexico all fall into this category), growth is expected to be about 26 percent. And low-fertility countries like China, Australia, and most of Europe will actually see population declines of approximately 20 percent. The graphs below illustrate this trend.

Changes in U.S. Immigration Patterns and Attitudes

Worldwide patterns of migration have changed, though the United States remains the most popular destination. From 1990 to 2013, the number of migrants living in the United States increased from one in six to one in five (The Pew Research Center 2013). Overall, in 2013 the United States was home to about 46 million foreign-born people, while only about 3 million U.S. citizens lived abroad. Of foreign-born citizens emigrating to the United States, 55 percent originated in Latin America and the Caribbean (Connor, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2013).

While there are more foreign-born people residing in the United States legally, as of 2012 about 11.7 million resided here without legal status (Passel, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2013). Most citizens agree that our national immigration policies are in need of major adjustment. Almost three-quarters of those in a recent national survey believed illegal immigrants should have a path to citizenship provided they meet other requirements, such as speaking English or paying restitution for the time they spent in the country illegally. Interestingly, 55 percent of those surveyed who identified as Hispanic think a pathway to citizenship is of secondary importance to provisions for living legally in the United States without the threat of deportation (The Pew Research Center 2013).

14.2 Urbanization

Learning Objectives

- Describe the process of urbanization in the United States and the growth of urban populations worldwide

- Understand the function of suburbs, exurbs, and concentric zones

- Discuss urbanization from various sociological perspectives

Urbanization is the study of the social, political, and economic relationships in cities, and someone specializing in urban sociology studies those relationships. In some ways, cities can be microcosms of universal human behavior, while in others they provide a unique environment that yields its own brand of human behavior. There is no strict dividing line between rural and urban; rather, there is a continuum where one bleeds into the other. However, once a geographically concentrated population has reached approximately 100,000 people, it typically behaves like a city regardless of what its designation might be.

The Growth of Cities

According to sociologist Gideon Sjoberg (1965), there are three prerequisites for the development of a city: First, a good environment with fresh water and a favorable climate; second, advanced technology, which will produce a food surplus to support nonfarmers; and third, a strong social organization to ensure social stability and a stable economy. Most scholars agree that the first cities were developed somewhere in ancient Mesopotamia, though there are disagreements about exactly where. Most early cities were small by today’s standards, and the largest was most likely Rome, with about 650,000 inhabitants (Chandler and Fox 1974). The factors limiting the size of ancient cities included a lack of adequate sewage control, limited food supply, and immigration restrictions. For example, serfs were tied to the land, and transportation was limited and inefficient. Today, the primary influence on cities’ growth is economic forces. Since the recent economic recession reduced housing prices, researchers have been waiting to see what happens to urban migration patterns in response.

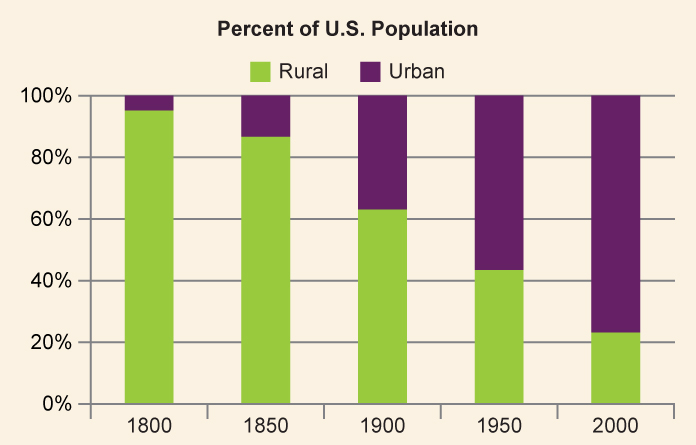

Urbanization in the United States

Urbanization in the United States proceeded rapidly during the Industrial Era. As more and more opportunities for work appeared in factories, workers left farms (and the rural communities that housed them) to move to the cities. From mill towns in Massachusetts to tenements in New York, the industrial era saw an influx of poor workers into U.S. cities. At various times throughout the country’s history, certain demographic groups, from post-Civil War southern Blacks to more recent immigrants, have made their way to urban centers to seek a better life in the city.

Sociology in the Real World

Managing Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in the Modern World

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) 2022, the number of people forced to flee violence, conflict, human rights violations, and persecution has crossed the milestone of 100 million for the first time on record, propelled by the war in Ukraine and other conflicts. Half of these people were children. A refugee is defined as an individual who has been forced to leave his or her country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster, while asylum-seekers are those whose claim to refugee status has not been validated. An internally displaced person, on the other hand, is neither a refugee nor an asylum-seeker. Displaced persons have fled their homes while remaining inside their country’s borders. The conflict in Ukraine beginning in 2022 has caused civilian casualties and destruction of civilian infrastructure, forcing people to flee their homes seeking safety, protection, and assistance. In the first five weeks, more than four million refugees from Ukraine crossed borders into neighboring countries, and many more have been forced to move inside the country. They are in need of protection and support (data.unhcr.org). In 2013, the war in Syria caused most of the 2013 increase, forcing 2.5 million people to seek refugee status while internally displacing an additional 6.5 million. Violence in the Central African Republic and South Sudan also contributed a large number of people to the total (The United Nations Refugee Agency 2014).

The refugees need help in the form of food, water, shelter, and medical care, which has worldwide implications for nations contributing foreign aid, the nations hosting the refugees, and the non-government organizations (NGOs) working with individuals and groups on site (The United Nations Refugee Agency 2014). Where will this large moving population, including the sick, elderly, children, and people with very few possessions and no long-term plan, go?

Suburbs and Exurbs

As cities grew more crowded, and often more impoverished and costly, more and more people began to migrate back out of them. But instead of returning to rural small towns (like they’d resided in before moving to the city), these people needed close access to the cities for their jobs. In the 1850s, as the urban population greatly expanded and transportation options improved, suburbs developed. Suburbs are the communities surrounding cities, typically close enough for a daily commute, but far enough away to allow for more space than city living affords. The bucolic suburban landscape of the early twentieth century has largely disappeared due to sprawl. Suburban sprawl contributes to traffic congestion, which in turn contributes to commuting time. And commuting times and distances have continued to increase as new suburbs developed farther and farther from city centers. Simultaneously, this dynamic contributed to an exponential increase in natural resource use, like petroleum, which sequentially increased pollution in the form of carbon emissions.

As the suburbs became more crowded and lost their charm, those who could afford them turned to the exurbs, communities that exist outside the ring of suburbs and are typically populated by even wealthier families who want more space and have the resources to lengthen their commute. Together, the suburbs, exurbs, and metropolitan areas all combine to form a metropolis. New York was the first U.S. megalopolis, a huge urban corridor encompassing multiple cities and their surrounding suburbs. These metropolises use vast quantities of natural resources and are a growing part of the U.S. landscape.

Social Policy and Debate

Suburbs Are Not All White Picket Fences: The Banlieues of Paris

What makes a suburb a suburb? Simply, a suburb is a community surrounding a city. But when you picture a suburb in your mind, your image may vary widely depending on which nation you call home. In the United States, most consider the suburbs home to upper— and middle—class people with private homes. In other countries, like France, the suburbs––or “banlieues”–– are synonymous with housing projects and impoverished communities. In fact, the banlieues of Paris are notorious for their ethnic violence and crime, with higher unemployment and more residents living in poverty than in the city center. Further, the banlieues have a much higher immigrant population, which in Paris is mostly Arabic and African immigrants. This contradicts the clichéd U.S. image of a typical white-picket-fence suburb.

In 2005, serious riots broke out in the banlieue of Clichy-sous-Bois after two boys were electrocuted while hiding from the police. They were hiding, it is believed, because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, near the scene of a break-in, and they were afraid the police would not believe in their innocence. Only a few days earlier, interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy (who later became president), had given a speech touting new measures against urban violence and referring to the people of the banlieue as “rabble” (BBC 2005). After the deaths and subsequent riots, Sarkozy reiterated his zero-tolerance policy toward violence and sent in more police. Ultimately, the violence spread across more than thirty towns and cities in France. Thousands of cars were burned, many hundreds of people were arrested, and both police and protesters suffered serious injuries.

Then-President Jacques Chirac responded by pledging more money for housing programs, jobs programs, and education programs to help the banlieues solve the underlying problems that led to such disastrous unrest. But none of the newly launched programs were effective. Sarkozy ran for president on a platform of tough regulations toward young offenders, and in 2007 the country elected him. More riots ensued as a response to his election. In 2010, Sarkozy promised “war without mercy” against the crime in the banlieues (France24 2010). Six years after the Clichy-sous-Bois riot, circumstances are no better for those in the banlieues.

As the Social Policy & Debate feature illustrates, the suburbs also have their share of socio-economic problems. In the United States, white flight refers to the migration of economically secure white people from racially mixed urban areas and toward the suburbs. This occurred throughout the twentieth century, due to causes as diverse as the legal end of racial segregation established by Brown v. Board of Education to the Mariel boatlift of Cubans fleeing Cuba’s Mariel port for Miami. Current trends include middle-class African-American families following white flight patterns out of cities, while affluent whites return to cities that have historically had a black majority. The result is that the issues of race, socio-economics, neighborhoods, and communities remain complicated and challenging.

Urbanization around the World

During the Industrial Era, there was a growth spurt worldwide. The development of factories brought people from rural to urban areas, and new technology increased the efficiency of transportation, food production, and food preservation. For example, from the mid-1670s to the early 1900s, London’s population increased from 550,000 to 7 million (Old Bailey Proceedings Online 2011). Global favorites like New York, London, and Tokyo are all examples of postindustrial cities. As cities evolve from manufacturing-based industrial to service- and information-based postindustrial societies, gentrification becomes more common. Gentrification occurs when members of the middle and upper classes enter and renovate city areas that have been historically less affluent while the poor urban underclass is forced by resulting price pressures to leave those neighborhoods for increasingly decaying portions of the city.

Globally, 54 percent of the world’s 7 billion people currently reside in urban areas, with the most urbanized region being North America (82 percent), followed by Latin America/the Caribbean (80 percent), with Europe coming in third (72 percent). In comparison, Africa is only 40 percent urbanized. With 38 million people, Tokyo is the world’s largest city by population. The world’s most densely populated cities are now largely concentrated in the global south, a marked change from several decades ago when the biggest cities were found in the global north. In the next forty years, the biggest global challenge for urbanized populations, particularly in less developed countries, will be to achieve development that occurs without depleting or damaging the natural environment, also called sustainable development (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2014).

Theoretical Perspectives on Urbanization

The issues of urbanization play significant roles in the study of sociology. Race, economics, and human behavior intersect in cities. Let’s look at urbanization through the sociological perspectives of functionalism and conflict theory. Functional perspectives on urbanization generally focus on the ecology of the city, while conflict perspective tends to focus on political economy.

Human ecology is a functionalist field of study that looks at the relationship between people and their built and natural physical environments (Park 1915). Generally speaking, urban land use and urban population distribution occur in a predictable pattern once we understand how people relate to their living environment. For example, in the United States, we have a transportation system geared to accommodate individuals and families in the form of interstate highways built for cars. In contrast, most parts of Europe emphasize public transportation such as high-speed rail and commuter lines, as well as walking and bicycling. The challenge for a human ecologist working in U.S. urban planning is to design landscapes and waterscapes with natural beauty, while also figuring out how to provide for free-flowing transport of innumerable vehicles, not to mention parking!

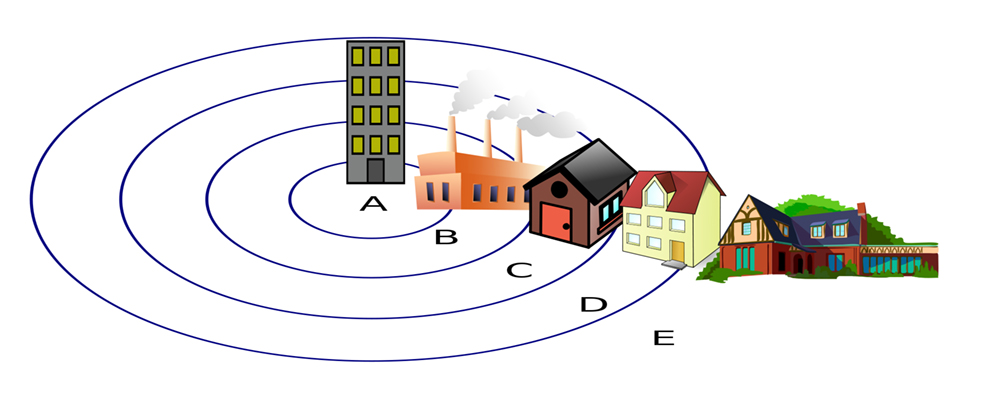

The concentric zone model (Burgess 1925) is perhaps the most famous example of human ecology. This model views a city as a series of concentric circular areas, expanding outward from the center of the city, with various “zones” invading adjacent zones (as new categories of people and businesses overrun the edges of nearby zones) and succeeding (then after the invasion, the new inhabitants repurpose the areas they have invaded and push out the previous inhabitants). In this model, Zone A, in the heart of the city, is the center of the business and cultural district. Zone B, the concentric circle surrounding the city center, is composed of formerly wealthy homes split into cheap apartments for new immigrant populations; this zone also houses small manufacturers, pawnshops, and other marginal businesses. Zone C consists of the homes of the working class and established ethnic enclaves. Zone D holds wealthy homes, white-collar workers, and shopping centers. Zone E contains the estates of the upper class (in the exurbs) and the suburbs.

In contrast to the functionalist approach, theoretical models in the conflict perspective focus on the way urban areas change according to specific decisions made by political and economic leaders. These decisions generally benefit the middle and upper classes while exploiting the working and lower classes.

For example, sociologists Feagin and Parker (1990) suggested three factors by which political and economic leaders control urban growth. First, these leaders work alongside each other to influence urban growth and decline, determining where money flows and how land use is regulated. Second, the exchange value and use-value of land are balanced to favor the middle and upper classes so that, for example, public land in poor neighborhoods may be rezoned for use as industrial land. Finally, urban development is dependent on both structure (groups such as local government) and agency (individuals including businessmen and activists), and these groups engage in a push-pull dynamic that determines where and how land is actually used. For example, Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) movements are more likely to emerge in middle and upper-class neighborhoods as engaged citizens protest poor environmental practices they fear will affect them, so these groups have more control over the use of local land.

14.3 The Environment and Society

Learning Objectives

- Describe climate change and its importance

- Apply the concept of carrying capacity to environmental concerns

- Understand the challenges presented by pollution, garbage, e-waste, and toxic hazards

- Discuss real-world instances of environmental racism

The subfield of environmental sociology studies the way humans interact with their environments. This field is closely related to human ecology, which focuses on the relationship between people and their built environments and the natural environment. This is an area that is garnering more attention as extreme weather patterns and policy battles over climate change dominate the news. A key factor of environmental sociology is the concept of carrying capacity, which describes the maximum amount of life that can be sustained within a given area. While this concept can refer to grazing lands or rivers, we can also apply it to the earth as a whole.

Big Picture

The Tragedy of the Commons

You might have heard the expression “the tragedy of the commons.” In 1968, an article of the same title written by Garrett Hardin described how a common pasture was ruined by overgrazing. But Hardin was not the first to notice the phenomenon. Back in the 1800s, Oxford economist William Forster Lloyd looked at the devastated public grazing commons and the unhealthy cattle subject to such limited resources, and saw, in essence, that the carrying capacity of the commons had been exceeded. However, since no one was held responsible for the land (as it was open to all), no one was willing to make sacrifices to improve it. Cattle grazers benefitted from adding more cattle to their herds, but they did not have to take on the responsibility for the lands that were being damaged by overgrazing. So there was an incentive for them to add more head of cattle, and no incentive for restraint.

Satellite photos of Africa taken in the 1970s showed this practice to dramatic effect. The images depicted a dark irregular area of more than 300 square miles. There was a large fenced area, where plenty of grass was growing. Outside the fence, the ground was bare and devastated. The reason was simple: the fenced land was privately owned by informed farmers who carefully rotated their grazing animals and allowed the fields to lie fallow periodically. Outside the fence was land used by nomads. Like the herdsmen in 1800s Oxford, the nomads increased their heads of cattle without planning for its impact on the greater good. The soil eroded, the plants died, then the cattle died, and, ultimately, some of the people died.

How does this lesson affect those of us who don’t need to graze our cattle? Well, like the cows, we all need food, water, and clean air to survive. With the increasing world population and the ever-larger megalopolises with tens of millions of people, the limit of the earth’s carrying capacity is called into question. When too many take while giving too little thought to the rest of the population, whether cattle or humans, the result is usually a tragedy.

Climate Change

While you might be more familiar with the phrase “global warming,” climate change is the term now used to refer to long-term shifts in temperatures due to human activity and, in particular, the release of greenhouse gases into the environment. The planet as a whole is warming, but the term climate change acknowledges that the short-term variations in this process can include both higher and lower temperatures, despite the overarching trend toward warmth.

Climate change is a deeply controversial subject, despite decades of scientific research and a high degree of scientific consensus that supports its existence. For example, according to NASA scientists, the years 2016 and 2020 are tied for the warmest years on record, continuing the overall trend of increasing worldwide temperatures (NASA 2022). One effect of climate change is more extreme weather. There are increasingly more record-breaking weather phenomena, from the number of Category 4 hurricanes to the amount of snowfall in a given winter. These extremes, while they make for dramatic television coverage, can cause immeasurable damage to crops, property, and even lives.

So why is there a controversy? The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) recognizes the existence of climate change. So do nearly 200 countries that signed the Kyoto Protocol, a document intended to engage countries’ involuntary actions to limit the activity that leads to climate change. (The United States was not one of the 200 nations committed to this initiative to reduce environmental damage, and its refusal to sign continues to be a source of contention.) What’s the argument about? For one thing, for companies making billions of dollars in the production of goods and services, the idea of costly regulations that would require expensive operational upgrades has been a source of great anxiety. They argue via lobbyists that such regulations would be disastrous for the economy. Some go so far as to question the science used as evidence. There is also a lot of finger-pointing among countries, especially when the issue arises of who will be permitted to pollute.

World-systems analysis suggests that while, historically, core nations (like the United States and Western Europe) were the greatest source of greenhouse gases, they have now evolved into postindustrial societies. Industrialized semi-peripheral and peripheral nations are releasing increasing quantities of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide. The core nations, now post-industrial and less dependent on greenhouse-gas-causing industries, wish to enact strict protocols regarding the causes of global warming, but the semi-peripheral and peripheral nations rightly point out that they only want the same economic chance to evolve their economies. Since they were unduly affected by the progress of core nations, if the core nations now insist on “green” policies, they should pay offsets or subsidies of some kind. There are no easy answers to this conflict. It may well not be “fair” that the core nations benefited from ignorance during their industrial boom.

The international community continues to work toward a way to manage climate change. During the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, the United States agreed to fund global climate change programs. In September 2010, President Obama announced the Global Climate Change Initiative (GCCI) as part of his administration’s Global Development Policy. The GCCI is a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding program intended to improve the economic and environmental sustainability of peripheral and semi-peripheral countries by encouraging the use of alternative, low-carbon, energy sources with financial incentives. Programming is organized around three pillars: (1) climate change adaptation, (2) clean energy, and (3) sustainable landscapes (Troilo 2012).

Pollution

Pollution describes what happens when contaminants are introduced into an environment (water, air, land) at levels that are damaging. Environments can often sustain a limited amount of contaminants without marked change, and water, air, and soil can “heal” themselves to a certain degree. However, once contaminant levels reach a certain point, the results can be catastrophic.

Water

Look at your watch. Wait fifteen seconds. Then wait another fifteen seconds. During that time, two children died from lack of access to clean drinking water. Access to safe water is one of the most basic human needs, and it is woefully out of reach for millions of people on the planet. Many of the major diseases that peripheral countries battle, such as diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid, are caused by contaminated water. Often, young children are unable to go to school because they must instead walk several hours a day just to collect potable water for their families. The situation is only getting direr as the global population increases. Water is a key resource battleground in the twenty-first century.

As every child learns in school, 70 percent of the earth is made of water. Despite that figure, there is a finite amount of water usable by humans and it is constantly used and reused in a sustainable water cycle. The way we use this abundant natural resource, however, renders much of it unsuitable for consumption and unable to sustain life. For instance, it takes two and a half liters of water to produce a single liter of Coca-Cola. The company and its bottlers use close to 300 billion liters of water a year, often in locales that are short of usable water (Blanchard 2007).

As a consequence of population concentrations, water close to human settlements is frequently polluted with untreated or partially treated human waste (sewage), chemicals, radioactivity, and levels of heat sufficient to create large “dead zones” incapable of supporting aquatic life. The methods of food production used by many-core nations rely on liberal doses of nitrogen and pesticides, which end up back in the water supply. In some cases, water pollution affects the quality of the aquatic life consumed by water and land animals. As we move along the food chain, the pollutants travel from prey to predator. Since humans consume at all levels of the food chain, we ultimately consume the carcinogens, such as mercury, accumulated through several branches of the food web.

Soil

You might have read The Grapes of Wrath in English class at some point in time. Steinbeck’s tale of the Joads, driven out of their home by the Dust Bowl, is still playing out today. In China, as in Depression-era Oklahoma, over-tilling soil in an attempt to expand agriculture has resulted in the disappearance of large patches of topsoil.

Soil erosion and desertification are just two of the many forms of soil pollution. In addition, all the chemicals and pollutants that harm our water supplies can also leach into the soil with similar effects. Brown zones where nothing can grow are common results of soil pollution. One demand the population boom makes on the planet is a requirement for more food to be produced. The so-called “Green Revolution” in the 1960s saw chemists and world aid organizations working together to bring modern farming methods, complete with pesticides, to developing countries. The immediate result was positive: food yields went up and burgeoning populations were fed. But as time has gone on, these areas have fallen into even more difficult straits as the damage done by modern methods leaves traditional farmers with less than they had to start.

Dredging certain beaches in an attempt to save valuable beachfront property from coastal erosion has resulted in greater storm impact on shorelines, and damage to beach ecosystems (Turneffe Atoll Trust 2008). These dredging projects have damaged reefs, seagrass beds, and shorelines and can kill off large swaths of marine life. Ultimately, this damage threatens local fisheries, tourism, and other parts of the local economy.

Garbage

Where is your last cell phone? What about the one before that? Or the huge old television set your family had before flat screens became popular? For most of us, the answer is a sheepish shrug. We don’t pay attention to the demise of old items, and since electronics drop in price and increase in innovation at an incredible clip, we have been trained by their manufacturers to upgrade frequently.

Garbage creation and control are major issues for most core and industrializing nations, and it is quickly becoming one of the most critical environmental issues faced in the United States. People in the United States buy products, use them, and then throw them away. Did you dispose of your old electronics according to government safety guidelines? Chances are good that you didn’t even know there were guidelines. Multiply your electronics times a few million, take into account the numerous toxic chemicals they contain, and then imagine either burying those chemicals in the ground or lighting them on fire.

Those are the two primary means of waste disposal in the United States: landfill and incineration. When it comes to getting rid of dangerous toxins, neither is a good choice. Styrofoam and plastics that many of us use every day do not dissolve in a natural way. Burn them, and they release carcinogens into the air. Their improper incineration (intentional or not) adds to air pollution and increases smog. Dump them in landfills, and they do not decompose. As landfill sites fill up, we risk an increase in groundwater contamination.

Big Picture

What Should Apple (and Friends) Do about E-Waste?

Electronic waste, or e-waste, is one of the fastest-growing segments of garbage. And it is far more problematic than even the mountains of broken plastic and rusty metal that plague the environment. E-waste is the name for obsolete, broken, and worn-out electronics—from computers to mobile phones to televisions. The challenge is that these products, which are multiplying at alarming rates thanks in part to planned obsolescence (the designing of products to quickly become outdated and then be replaced by the constant emergence of newer and cheaper electronics), have toxic chemicals and precious metals in them, which makes for a dangerous combination.

So where do they go? Many companies ship their e-waste to developing nations in Africa and Asia to be “recycled.” While they are, in some senses, recycled, the result is not exactly clean. In fact, it is one of the dirtiest jobs around. Overseas, without the benefit of environmental regulation, e-waste dumps become a kind of boomtown for entrepreneurs willing to sort through endless stacks of broken-down electronics for tiny bits of valuable copper, silver, and other precious metals. Unfortunately, in their hunt, these workers are exposed to deadly toxins.

Governments are beginning to take notice of the impending disaster, and the European Union, as well as the state of California, put stricter regulations in place. These regulations both limit the number of toxins allowed in electronics and address the issue of end-of-life recycling. But not surprisingly, corporations, while insisting they are greening their process, often fight stricter regulations. Meanwhile, many environmental groups, including the activist group Greenpeace, have taken up the cause. Greenpeace states that it is working to get companies to:

- measure and reduce emissions with energy efficiency, renewable energy, and energy policy advocacy

- make greener, more efficient, longer-lasting products that are free of hazardous substances

- reduce environmental impacts throughout company operations, from choosing production materials and energy sources right through to establishing global take-back programs for old products (Greenpeace 2011).

Greenpeace produces annual ratings of how well companies are meeting these goals so consumers can see how brands stack up. For instance, Apple moved from ranking fourth overall to sixth overall from 2011 to 2012. The hope is that consumers will vote with their wallets, and the greener companies will be rewarded.

Air

China’s fast-growing economy and burgeoning industry have translated into notoriously poor air quality. Smog hangs heavily over the major cities, sometimes grounding aircraft that cannot navigate through it. Pedestrians and cyclists wear air-filter masks to protect themselves. In Beijing, citizens are skeptical that the government-issued daily pollution ratings are trustworthy. Increasingly, they are taking their own pollution measurements in the hopes that accurate information will galvanize others to action. Given that some days they can barely see down the street, they hope action comes soon (Papenfuss 2011).

Humanity, with its growing numbers, use of fossil fuels, and increasingly urbanized society, is putting too much stress on the earth’s atmosphere. The amount of air pollution varies from locale to locale, and you may be more personally affected than you realize. How often do you check air quality reports before leaving your house? Depending on where you live, this question can sound utterly strange or like an everyday matter. Along with oxygen, most of the time we are also breathing in soot, hydrocarbons, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur oxides.

Much of the pollution in the air comes from human activity. How many college students move their cars across campus at least once a day? Who checks the environmental report card on how many pollutants each company throws into the air before purchasing a cell phone? Many of us are guilty of taking our environment for granted without concern for how everyday decisions add up to a long-term global problem. How many minor adjustments can you think of, like walking instead of driving, that would reduce your overall carbon footprint?

Remember the “tragedy of the commons.” Each of us is affected by air pollution. But like the herder who adds one more head of cattle to realize the benefits of owning more cows but who does not have to pay the price of the overgrazed land, we take the benefit of driving or buying the latest cell phones without worrying about the end result. Air pollution accumulates in the body, much like the effects of smoking cigarettes accumulate over time, leading to more chronic illnesses. And in addition to directly affecting human health, air pollution affects crop quality as well as heating and cooling costs. In other words, we all pay a lot more than the price at the pump when we fill up our tanks with gas.

Toxic and Radioactive Waste

Radioactivity is a form of air pollution. While nuclear energy promises a safe and abundant power source, increasingly it is looked upon as a danger to the environment and to those who inhabit it. We accumulate nuclear waste, which we must then keep track of long-term and ultimately figure out how to store the toxic waste material without damaging the environment or putting future generations at risk.

The 2011 earthquake in Japan illustrates the dangers of even safe, government-monitored nuclear energy. When a disaster occurs, how can we safely evacuate the large numbers of affected people? Indeed, how can we even be sure how far the evacuation radius should extend? Radiation can also enter the food chain, causing damage from the bottom (phytoplankton and microscopic soil organisms) all the way to the top. Once again, the price paid for cheap power is much greater than what we see on the electric bill.

The enormous oil disaster that hit the Louisiana Gulf Coast in 2010 is just one of a high number of environmental crises that have led to toxic residue. They include the pollution of the Love Canal neighborhood of the 1970s, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker crash of 1989, the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, and Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant incident following the earthquake in 2011. Often, the stories are not newsmakers, but simply an unpleasant part of life for the people who live near toxic sites such as Centralia, Pennsylvania, and Hinkley, California. In many cases, people in these neighborhoods can be part of a cancer cluster without realizing the cause.

Sociology in the Real World

The Fire Burns On: Centralia, Pennsylvania

There used to be a place called Centralia, Pennsylvania. The town was incorporated in the 1860s and once had several thousand residents, largely coal workers. But the story of its demise begins a century later in 1962. That year, a trash-burning fire was lit in the pit of the old abandoned coal mine outside of town. The fire moved down the mineshaft and ignited a vein of coal. It is still burning.

For more than twenty years, people tried to extinguish the underground fire, but no matter what they did, it returned. There was little government action, and people had to abandon their homes as toxic gases engulfed the area and sinkholes developed. The situation drew national attention when the ground collapsed under twelve-year-old Todd Domboski in 1981. Todd was in his yard when a sinkhole four feet wide and 150 feet deep opened beneath him. He clung to exposed tree roots and saved his life; if he had fallen a few feet farther, the heat or carbon monoxide would have killed him instantly.

In 1983, engineers studying the fire concluded that it could burn for another century or more and could spread over nearly 4,000 acres. At this point, the government offered to buy out the town’s residents and wanted them to relocate to nearby towns. A few determined Centralians refused to leave, even though the government bought their homes, and they are the only ones who remain. In one field, signs warn people to enter at their own risk, because the ground is hot and unstable. And the fire burns on (DeKok 1986).

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism refers to the way in which minority group neighborhoods (populated primarily by people of color and members of low socioeconomic groups) are burdened with a disproportionate number of hazards, including toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollution and foul odors that lower the quality of life. All around the globe, members of minority groups bear a greater burden of health problems that result from higher exposure to waste and pollution. This can occur due to unsafe or unhealthy work conditions where no regulations exist (or are enforced) for poor workers, or in neighborhoods that are uncomfortably close to toxic materials.

The statistics on environmental racism are shocking. Research shows that it pervades all aspects of African Americans’ lives: environmentally unsound housing, schools with asbestos problems, facilities, and playgrounds with lead paint. A twenty-year comparative study led by sociologist Robert Bullard determined “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities” (Bullard et al. 2007). His research found, for example, that Black children are five times more likely to have lead poisoning (the leading environmental health threat for children) than their White counterparts, and that a disproportionate number of people of color reside in areas with hazardous waste facilities (Bullard et al. 2007). Sociologists with the project are examining how environmental racism is addressed in the long-term cleanup of the environmental disasters caused by Hurricane Katrina.

Sociology in the Real World

American Indian Tribes and Environmental Racism

Native Americans are unquestionably victims of environmental racism. The Commission for Racial Justice found that about 50 percent of all American Indians live in communities with uncontrolled hazardous waste sites (Asian Pacific Environmental Network 2002). There’s no question that, worldwide, indigenous populations are suffering from similar fates.

For Native American tribes, the issues can be complicated—and their solutions hard to attain—because of the complicated governmental issues arising from a history of institutionalized disenfranchisement. Unlike other racial minorities in the United States, Native American tribes are sovereign nations. However, much of their land is held in “trust,” meaning that “the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe” (Bureau of Indian Affairs 2012). Some instances of environmental damage arising from this crossover, where the U.S. government’s title has meant it acts without the approval of the tribal government. Other significant contributors to environmental racism as experienced by tribes are forcible removal and burdensome red tape to receive the same reparation benefits afforded to non-Indians.

To better understand how this happens, let’s consider a few example cases. The home of the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians was targeted as the site for a high-level nuclear waste dumping ground, amid allegations of a payoff of as high as $200 million (Kamps 2001). Keith Lewis, an indigenous advocate for Indian rights, commented on this buyout, after his people endured decades of uranium contamination, saying that “there is nothing moral about tempting a starving man with money” (Kamps 2001). In another example, the Western Shoshone’s Yucca Mountain area has been pursued by mining companies for its rich uranium stores, a threat that adds to the existing radiation exposure this area suffers from U.S. and British nuclear bomb testing (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004). In the “four corners” area where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet, a group of Hopi and Navajo families have been forcibly removed from their homes so the land could be mined by the Peabody Mining Company for coal valued at $10 billion (American Indian Cultural Support 2006). Years of uranium mining on the lands of the Navajo of New Mexico have led to serious health consequences, and reparations have been difficult to secure; in addition to the loss of life, people’s homes and other facilities have been contaminated (Frosch 2009). In yet another case, members of the Chippewa near White Pine, Michigan, were unable to stop the transport of hazardous sulfuric acid across reservation lands, but their activism helped bring an end to the mining project that used the acid (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004).

These examples are only a few of the hundreds of incidents that American Indian tribes have faced and continue to battle against. Sadly, the mistreatment of the land’s original inhabitants continues via this institution of environmental racism. How might the work of sociologists help draw attention to—and eventually mitigate—this social problem?

Why does environmental racism exist? The reason is simple. Those with resources can raise awareness, money, and public attention to ensure that their communities are unsullied. This has led to an inequitable distribution of environmental burdens. Another method of keeping this inequity alive is NIMBY protests. Chemical plants, airports, landfills, and other municipal or corporate projects are often the subject of NIMBY demonstrations. And equally often, the NIMBYists win, and the objectionable project is moved closer to those who have fewer resources to fight it.

Key Terms

- sustainable development

- development that occurs without depleting or damaging the natural environment

- asylum-seekers

- those whose claims to refugee status have not been validated

- cancer cluster

- a geographic area with high levels of cancer within its population

- carrying capacity

- the amount of people that can live in a given area considering the amount of available resources

- climate change

- long-term shifts in temperature and climate due to human activity

- concentric zone model

- a model of human ecology that views cities as a series of circular rings or zones

- cornucopian theory

- a theory that asserts human ingenuity will rise to the challenge of providing adequate resources for a growing population

- demographic transition theory

- a theory that describes four stages of population growth, following patterns that connect birth and death rates with stages of industrial development

- demography

- the study of population

- e-waste

- the disposal of broken, obsolete, and worn-out electronics

- environmental racism

- the burdening of economically and socially disadvantaged communities with a disproportionate share of environmental hazards

- environmental sociology

- the sociological subfield that addresses the relationship between humans and the environment

- exurbs

- communities that arise farther out than the suburbs and are typically populated by residents of high socioeconomic status

- fertility rate

- a measure noting the actual number of children born

- fracking

- hydraulic fracturing, a method used to recover gas and oil from shale by drilling down into the earth and directing a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and proprietary chemicals into the rock

- gentrification

- the entry of upper- and middle-class residents to city areas or communities that have been historically less affluent

- human ecology

- a functional perspective that looks at the relationship between people and their built and natural environment

- internally displaced person

- someone who fled his or her home while remaining inside the country’s borders

- Malthusian theory

- a theory asserting that population is controlled through positive checks (war, famine, disease) and preventive checks (measures to reduce fertility)

- megalopolis

- a large urban corridor that encompasses several cities and their surrounding suburbs and exurbs

- metropolis

- the area that includes a city and its suburbs and exurbs

- mortality rate

- a measure of the number of people in a population who die

- NIMBY

- “Not In My Back Yard,” the tendency of people to protest poor environmental practices when those practices will affect them directly

- pollution

- the introduction of contaminants into an environment at levels that are damaging

- population composition

- a snapshot of the demographic profile of a population based on fertility, mortality, and migration rates

- population pyramid

- a graphic representation that depicts population distribution according to age and sex

- refugee

- an individual who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster

- sex ratio

- the ratio of men to women in a given population

- suburbs

- the communities surrounding cities, typically close enough for a daily commute

- urban sociology

- the subfield of sociology that focuses on the study of urbanization

- urbanization

- the study of the social, political, and economic relationships of cities

- white flight

- the migration of economically secure white people from racially mixed urban areas toward the suburbs

- zero population growth

- a theoretical goal in which the number of people entering a population through birth or immigration is equal to the number of people leaving it via death or emigration

Section Summary

14.1 Demography and Population

Scholars understand demography through various analyses. Malthusian, zero population growth, cornucopian theory, and demographic transition theories all help sociologists study demography. The earth’s human population is growing quickly, especially in peripheral countries. Factors that impact population include birthrates, mortality rates, and migration, including immigration and emigration. There are numerous potential outcomes of the growing population, and sociological perspectives vary on the potential effect of these increased numbers. The growth will pressure the already-taxed planet and its natural resources.

14.2 Urbanization

Cities provide numerous opportunities for their residents and offer significant benefits including access to goods to numerous job opportunities. At the same time, high-population areas can lead to tensions between demographic groups, as well as environmental strain. While the population of urban dwellers is continuing to rise, sources of social strain are rising along with it. The ultimate challenge for today’s urbanites is finding an equitable way to share the city’s resources while reducing the pollution and energy use that negatively impacts the environment.

14.3 The Environment and Society

The area of environmental sociology is growing as extreme weather patterns and concerns over climate change increase. Human activity leads to pollution of soil, water, and air, compromising the health of the entire food chain. While everyone is at risk, poor and disadvantaged neighborhoods and nations bear a greater burden of the planet’s pollution, a dynamic known as environmental racism.

Section Quizzes

14.1 Demography and Population

1. The population of the planet doubled in fifty years to reach _______ in 1999.

- 6 billion

- 7 billion

- 5 billion

- 10 billion

2. A functionalist would address which issue?

- The way inner-city areas become ghettoized and limit the availability of jobs

- The way immigration and emigration trends strengthen global relationships

- The way racism and sexism impact the population composition of rural communities

- The way humans interact with environmental resources on a daily basis

3. What does carrying capacity refer to?

- The ability of a community to welcome new immigrants

- The capacity for globalism within a given ethnic group

- The amount of life that can be supported sustainably in a particular environment

- The amount of weight that urban centers can bear if vertical growth is mandated

4. What three factors did Malthus believe would limit the human population?

- Self-preservation, old age, and illness

- Natural cycles, illness, and immigration

- Violence, new diseases, and old age

- War, famine, and disease

5. What does cornucopian theory believe?

- That human ingenuity will solve any issues that overpopulation creates

- That new diseases will always keep populations stable

- That the earth will naturally provide enough for whatever number of humans exist

- That the greatest risk is population reduction, not population growth

14.2 Urbanization

- The city’s industrial center

- Wealthy commuter homes

- Formerly wealthy homes split into cheap apartments

- Rural outposts

7. What are the prerequisites for the existence of a city?

- Good environment with water and a favorable climate

- Advanced agricultural technology

- Strong social organization

- All of the above

8. In 2014, what was the largest city in the world?

- Delhi

- New York

- Shanghai

- Tokyo

9. What led to the creation of the exurbs?

- Urban sprawl and crowds moving into the city

- The high cost of suburban living

- The housing boom of the 1980s

- Gentrification

10. How are the suburbs of Paris different from those of most U.S. cities?

- They are connected by public transportation.

- There are more industrial and business opportunities there.

- They are synonymous with housing projects and the urban poor.

- They are less populated.

11. How does gentrification affect cities?

- They become more crowded.

- Less affluent residents are pushed into less desirable areas.

- Traffic issues, including pollution, become worse.

- All of the above

12. What does human ecology theory address?

- The relationship between humans and their environments

- The way humans affect technology

- The way the human population reduces the variety of nonhuman species

- The relationship between humans and other species

13. Urbanization includes the sociological study of what?

- Urban economics

- Urban politics

- Urban environments

- All of the above

14.3 The Environment and Society

- Global warming

- African landowners

- The common grazing lands in Oxford

- The misuse of private space

15. What are ways that human activity impacts the water supply?

- Creating sewage

- Spreading chemicals

- Increasing radioactivity

- All of the above

16. Which is an example of environmental racism?

- The fact that a disproportionate percentage of people of color live in environmentally hazardous areas

- Greenpeace protests

- The prevalence of asbestos in formerly “whites only” schools

- Prejudice similar to racism against people with different environmental views than one’s own

17. What is not a negative outcome of shoreline dredging?

- Damaged coral reefs

- Death of marine life

- Ruined seagrass beds

- Reduction of the human population

18. What are the two primary methods of waste disposal?

- Landfill and incineration

- Incineration and compost

- Decomposition and incineration

- Marine dumping and landfills

19. Where does a large percentage of e-waste wind up?

- Incinerators

- Recycled in peripheral nations

- Repurposed into new electronics

- Dumped into ocean repositories

20. What types of municipal projects often result in environmental racism?

- Toxic dumps or other objectionable projects

- The location of schools, libraries, and other cultural institutions

- Hospitals and other health and safety sites

- Public transportation options

Short Answer

14.1 Demography and Population

14.2 Urbanization

14.3 The Environment and Society

Future Research

14.1 Demography and Population

To learn more about population concerns, from the new-era ZPG advocates to the United Nations reports, check out these links: http://openstax.org/l/population_connection and http://openstax.org/l/un-population

14.2 Urbanization

Interested in learning more about the latest research in the field of human ecology? Visit the Society for Human Ecology website to discover what’s emerging in this field: http://openstax.org/l/human_ecology

Getting from place to place in urban areas might be more complicated than you think. Read the latest on pedestrian-traffic concerns at the Urban Blog website: http://openstax.org/l/pedestrian_traffic

14.3 The Environment and Society

Visit the Cleanups in My Community website: http://openstax.org/l/community_cleanup to see where environmental hazards have been identified in your backyard, and what is being done about them.

What is your carbon footprint? Find out using the carbon footprint calculator at http://openstax.org/l/carbon_footprint_calculator

Find out more about greening the electronics process by looking at Greenpeace’s guide: http://openstax.org/l/greenpeace_electronics

References

Introduction to Population, Urbanization, and the Environment

Colborn, Theo, Carol Kwiatkowski, Kim Schultz, and Mary Bachran. 2011. “Natural Gas Operations from a Public Health Perspective.” Human & Ecological Risk Assessment 17 (5): 1039-1056.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2014. “EPA’s Study of Hydraulic Fracturing and Its Potential Impact on Drinking Water Resources.” U.S. EPA, September 14. Retrieved October 29, 2014. (http://www2.epa.gov/hfstudy).

Henry, Terrence. 2012. “How Fracking Disposal Wells Are Causing Earthquakes in Dallas-Fort Worth.” Texas RSS. N.p., August 6. Retrieved October 29, 2014 (http://stateimpact.npr.org/texas/2012/08/06/how-fracking-disposal-wells-are-causing-earthquakes-in-dallas-fort-worth/).

IHS Global Insights. 2012. “The Economic and Employment Contributions of Unconventional Gas Development in State Economies.” Prepared for America’s Natural Gas Alliance, June 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2014 (http://www.anga.us/media/content/F7D4500D-DD3A-1073-DA3480BE3CA41595/files/state_unconv_gas_economic_contribution.pdf).

14.1 Demography and Population

Caldwell, John Charles and Bruce Caldwell. 2006. Demographic Transition Theory. The Netherlands: Springer.

CIA World Factbook. 2014. “Guide to Country Comparisons.” Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook. Retrieved October 31, 2014 (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/rankorderguide.html).

Colborn, Theo, Carol Kwiatkowski, Kim Schultz, and Mary Bachran. 2011. “Natural Gas Operations from a Public Health Perspective.” Human & Ecological Risk Assessment. 17 (5): 1039-1056

Connor, Phillip, D’Vera Cohn, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. 2013. “Changing Patterns of Global Migration and Remittances.” Pew Research Centers Social Demographic Trends Project RSS. N.p., Retrieved October 31, 2014 (http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/12/17/changing-patterns-of-global-migration-and-remittances/).

Dart, Tom. 2014. “Child Migrants at Texas Border: An Immigration Crisis That’s Hardly New.” The Guardian [Houston]. www.theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved October 30, 2014 (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/09/us-immigration-undocumented-children-texas).

Ehrlich, Paul R. 1968. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2014. “EPA’s Study of Hydraulic Fracturing and Its Potential Impact on Drinking Water Resources.” U.S. EPA, September 14. Retrieved October 29, 2014. (http://www2.epa.gov/hfstudy).

Fox News, and Associated Press. 2014. “Protests Turn Back Buses Carrying Illegal Immigrant Children.” Fox News. FOX News Network. Retrieved October 30, 2014 (http://www.foxnews.com/us/2014/07/02/protests-force-buses-carrying-illegal-immigrant-children-to-be-rerouted/).

Henry, Terrence. 2012. “How Fracking Disposal Wells Are Causing Earthquakes in Dallas-Fort Worth.” Texas RSS. N.p., August 6. Retrieved October 29, 2014 (http://stateimpact.npr.org/texas/2012/08/06/how-fracking-disposal-wells-are-causing-earthquakes-in-dallas-fort-worth/).

IHS Global Insights. 2012. “The Economic and Employment Contributions of Unconventional Gas Development in State Economies.” Prepared for America’s Natural Gas Alliance, June 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2014. (http://www.anga.us/media/content/F7D4500D-DD3A-1073-DA3480BE3CA41595/files/state_unconv_gas_economic_contribution.pdf).

Malthus, Thomas R. 1965 [1798]. An Essay on Population. New York: Augustus Kelley.

Mazur, A. (2016). How did the fracking controversy emerge in the period 2010–2012? Public Understand. Sci. 25, 207–222. doi: 10.1177/0963662514545311

Murphy, M. (2020). “We Are Seneca Lake”: Defining the Substances of Sustainable and Extractive Economics Through Anti-Fracking Activism. Front. Commun. 5 (27), 1–12. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.00027

Operational Data Portal (2022), The UN Refugee Agency, Refugees fleeing Ukraine since 24 February 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022 (HTTP://www.Data.unhcr.org)

Passel, Jeffrey, D’Vera Cohn, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. 2013. “Population Decline of Unauthorized Immigrants Stalls, May Have Reversed.” Pew Research Centers Hispanic Trends Project RSS. N.p., Retrieved October 31, 2014 (http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/09/23/population-decline-of-unauthorized-immigrants-stalls-may-have-reversed/).

Pew Research Center. 2013. “Immigration: Key Data Points from Pew Research.” Pew Research Center RSS. N.p., Retrieved October 31, 2014 (http://www.pewresearch.org/key-data-points/immigration-tip-sheet-on-u-s-public-opinion/).

Popescu, Roxana. 2014. “Frequently Asked Questions about the Migrant Crisis.” U-T San Diego. San Diego Union-Tribue, Retrieved October 31, 2014 (http://www.utsandiego.com/news/2014/jul/22/Migrant-crisis-FAQ/).

Reyes, Raul A. 2014. “Murrieta Immigration Protests Were Unfortunate, Unnecessary.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Retrieved October 31, 2014 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/raul-a-reyes/murrieta-immigration-prot_b_5569351.html).

Siegfried, Kristy (2022) The Refugee Brief May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022 (HTTP://www.unhcr.org/refugeebrief/latest-issues/)

Simon, Julian Lincoln. 1981. The Ultimate Resource. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1.

The United Nations Refugee Agency. 2014. “World Refugee Day: Global Forced Displacement Tops 50 Million for First Time in Post-World War II Era.” UNHCR News. N.p., Retrieved October 31, 2014(http://www.unhcr.org/53a155bc6.html).

U.S. Congress. 2008. The William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. 7311, 110 Cong., U.S. G.P.O. (enacted). Print.

14.2 Urbanization

BBC. 2005. “Timeline: French Riots—A Chronology of Key Events.” November 14. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4413964.stm).

Burgess, Ernest. 1925. “The Growth of the City.” Pp. 47–62 in The City, edited by R. Park and E. Burgess. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chandler, Tertius and Gerald Fox. 1974. 3000 Years of Urban History. New York: Academic Press.

Dougherty, Connor. 2008. “The End of White Flight.” Wall Street Journal, July 19. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121642866373567057.html).