6 Social Stratification and Inequality

Eric grew up on a farm in rural Ohio, left home to serve in the Army, and returned to take over the family farm a few years later. He moved into the same house he had grown up in and soon married a young woman with whom he had attended high school. As they began to have children, they quickly realized that the income from the farm was no longer sufficient to meet their needs. With little experience beyond the farm, Eric accepted a job as a clerk at a local grocery store. It was there that his life and the lives of his wife and children were changed forever.

One of the managers at the store liked Eric, his attitude, and his work ethic. He took Eric under his wing and began to groom him for advancement at the store. Eric rose through the ranks with ease. Then the manager encouraged him to take a few classes at a local college. This was the first time Eric had seriously thought about college. Could he be successful, Eric wondered? Could he actually be the first to earn a degree in his family? Fortunately, his wife also believed in him and supported his decision to take his first class. Eric asked his wife and his manager to keep his college enrollment a secret. He did not want others to know about it in case he failed.

Eric was nervous on his first day of class. He was older than the other students, and he had never considered himself college material. Through hard work and determination, however, he did very well in the class. While he still doubted himself, he enrolled in another class. Again, he performed very well. As his doubt began to fade, he started to take more and more classes. Before he knew it, he was walking across the stage to receive a Bachelor’s degree with honors. The ceremony seemed surreal to Eric. He couldn’t believe he had finished college, which once seemed like an impossible feat.

Shortly after graduation, Eric was admitted into a graduate program at a well-respected university, where he earned a Master’s degree. He had not only become the first in his family to attend college but also earned a graduate degree. Inspired by Eric’s success, his wife enrolled at a technical college, obtained a degree in nursing, and became a registered nurse working in a local hospital’s labor and delivery department. Eric and his wife both worked their way up the career ladder in their respective fields and became leaders in their organizations. They epitomized the American Dream—they worked hard and it paid off.

This story may sound familiar. After all, nearly one in three first-year college students is a first-generation degree candidate, and it is well documented that many are not as successful as Eric. According to the Center for Student Opportunity, a national nonprofit, 89 percent of first-generation students will not earn an undergraduate degree within six years of starting their studies. In fact, these students “drop out of college at four times the rate of peers whose parents have postsecondary degrees” (Center for Student Opportunity quoted in Huot 2014).

Why do students with parents who have completed college tend to graduate more often than those students whose parents do not hold degrees? That question and many others will be answered as we explore social stratification.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between open and closed stratification systems

- Distinguish between caste and class systems

- Understand meritocracy as an ideal system of stratification

Sociologists use the term social stratification to describe the system of social standing. Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings of socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power.

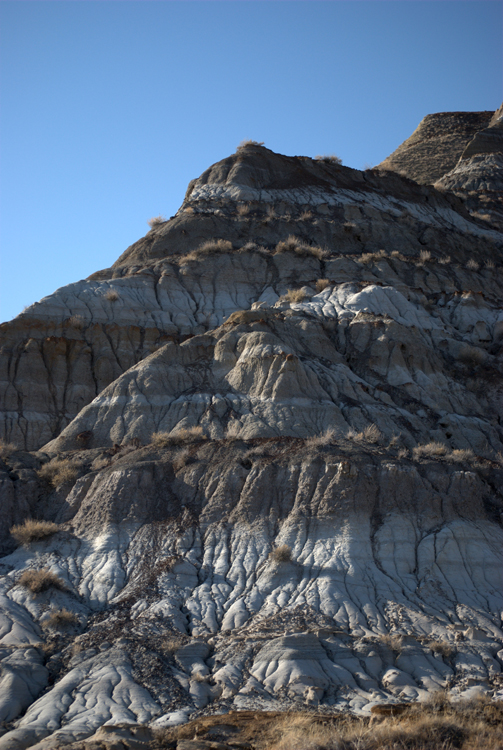

You may remember the word “stratification” from geology class. The distinct vertical layers found in rock, called stratification, are a good way to visualize the social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. The people who have more resources represent the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with progressively fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers of our society.

In the United States, people like to believe everyone has an equal chance at success. To a certain extent, Aaron illustrates the belief that hard work and talent—not prejudicial treatment or societal values—determine social rank. This emphasis on self-effort perpetuates the belief that people control their own social standing.

However, sociologists recognize that social stratification is a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent. While there are always inequalities between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Stratification is not about individual inequalities but about systemic inequalities based on group membership, classes, and the like. No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities. The structure of a society affects a person’s social standing. Although individuals may support or fight inequalities, social stratification is created and supported by society as a whole.

Factors that define stratification vary in different societies. In most societies, stratification is an economic system, based on wealth, the net value of money and assets a person has, and income, a person’s wages or investment dividends. While people are regularly categorized based on how rich or poor they are, other important factors influence social standing. For example, in some cultures, wisdom and charisma are valued, and people who have them are revered more than those who don’t. In some cultures, the elderly are esteemed; in others, the elderly are disparaged or overlooked. Societies’ cultural beliefs often reinforce the inequalities of stratification.

One key determinant of social standing is the social standing of our parents. Parents tend to pass their social position on to their children. People inherit not only social standing but also the cultural norms that accompany a certain lifestyle. They share these with a network of friends and family members. Social standing becomes a comfort zone, a familiar lifestyle, and an identity. This is one of the reasons first-generation college students do not fare as well as other students.

Other determinants are found in a society’s occupational structure. Teachers, for example, often have high levels of education but receive relatively low pay. Many believe that teaching is a noble profession, so teachers should do their jobs for the love of their profession and the good of their students—not for money. Yet no successful executive or entrepreneur would embrace that attitude in the business world, where profits are valued as a driving force. Cultural attitudes and beliefs like these support and perpetuate social inequalities.

Recent Economic Changes and U.S. Stratification

As a result of the Great Recession that rocked our nation’s economy in the last few years, many families and individuals found themselves struggling like never before. The nation fell into a period of prolonged and exceptionally high unemployment. While no one was completely insulated from the recession, perhaps those in the lower classes felt the impact most profoundly. Before the recession, many were living paycheck to paycheck or even had been living comfortably. As the recession hit, they were often among the first to lose their jobs. Unable to find replacement employment, they faced more than a loss of income. Their homes were foreclosed, their cars were repossessed, and their ability to afford healthcare was taken away. This put many in the position of deciding whether to put food on the table or fill a needed prescription.

While we’re not completely out of the woods economically, there are several signs that we’re on the road to recovery. Many of those who suffered during the recession are back to work and are busy rebuilding their lives. The Affordable Health Care Act has provided health insurance to millions who lost or never had it.

But the Great Recession, like the Great Depression, has changed social attitudes. Where once it was important to demonstrate wealth by wearing expensive clothing items like Calvin Klein shirts and Louis Vuitton shoes, now there’s a new, thriftier way of thinking. In many circles, it has become hip to be frugal. It’s no longer about how much we spend, but about how much we don’t spend. Think of shows like Extreme Couponing on TLC and songs like Macklemore’s “Thrift Shop.”

Systems of Stratification

Sociologists distinguish between two types of systems of stratification. Closed systems accommodate little change in social position. They do not allow people to shift levels and do not permit social relationships between levels. Open systems, which are based on achievement, allow movement and interaction between layers and classes. Different systems reflect, emphasize, and foster certain cultural values and shape individual beliefs. Stratification systems include class systems and caste systems, as well as a meritocracy.

The Caste System

Caste systems are closed stratification systems in which people can do little or nothing to change their social standing. A caste system is one in which people are born into their social standing and will remain in it their whole lives. People are assigned occupations regardless of their talents, interests, or potential. There are virtually no opportunities to improve a person’s social position.

In the Hindu caste tradition, people were expected to work in the occupation of their caste and to enter into marriage according to their caste. Accepting this social standing was considered a moral duty. Cultural values reinforced the system. Caste systems promote beliefs in fate, destiny, and the will of a higher power, rather than promoting individual freedom as a value. A person who lived in a caste society was socialized to accept his or her social standing.

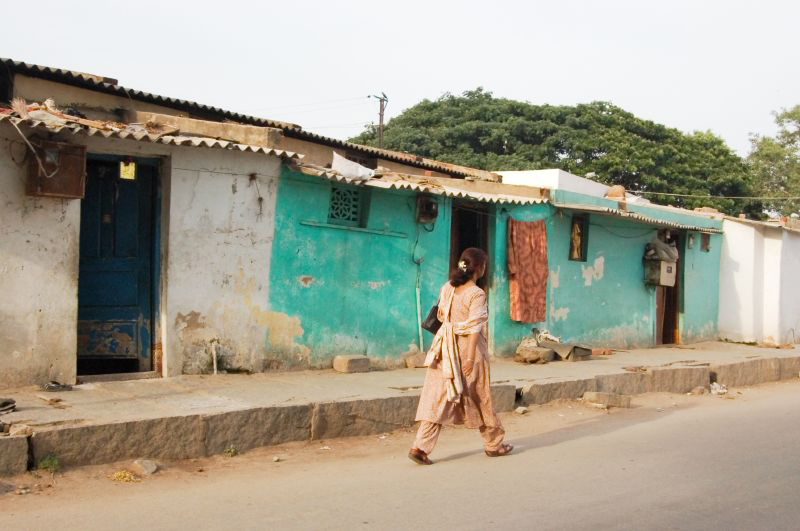

Although the caste system in India has been officially dismantled, its residual presence in Indian society is deeply embedded. In rural areas, aspects of the tradition are more likely to remain, while urban centers show less evidence of this past. In India’s larger cities, people now have more opportunities to choose their own career paths and marriage partners. As a global center of employment, corporations have introduced merit-based hiring and employment to the nation.

The Class System

A class system is based on both social factors and individual achievement. A class consists of a set of people who share similar status with regard to factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Unlike caste systems, class systems are open. People are free to gain a different level of education or employment than their parents. They can also socialize with and marry members of other classes, which allows people to move from one class to another.

In a class system, occupation is not fixed at birth. Though family and other societal models help guide a person toward a career, personal choice plays a role.

In class systems, people have the option to form exogamous marriages and unions of spouses from different social categories. Marriage in these circumstances is based on values such as love and compatibility rather than on social standing or economics. Though social conformities still exist that encourage people to choose partners within their own class, people are not as pressured to choose marriage partners based solely on those elements. Marriage to a partner from the same social background is an endogamous union.

Meritocracy

Meritocracy is an ideal system based on the belief that social stratification is the result of personal effort—or merit—that determines social standing. High levels of effort will lead to a high social position and vice versa. The concept of meritocracy is ideal—because a society has never existed where social rank was based purely on merit. Because of the complex structures of societies, processes like socialization, and the realities of economic systems, social standing is influenced by multiple factors—not merit alone. Inheritance and pressure to conform to norms, for instance, disrupt the notion of a pure meritocracy. While a meritocracy has never existed, sociologists see aspects of meritocracies in modern societies when they study the role of academic and job performance and the systems in place for evaluating and rewarding achievement in these areas.

Status Consistency

Social stratification systems determine social position based on factors like income, education, and occupation. Sociologists use the term status consistency to describe the consistency, or lack thereof, of an individual’s rank across these factors. Caste systems correlate with high-status consistency, whereas the more flexible class system has lower status consistency.

To illustrate, let’s consider Susan. Susan earned her high school degree but did not go to college. That factor is a trait of the lower-middle class. She began doing landscaping work, which, like other manual labor, is also a trait of the lower-middle class or even lower class. However, over time, Susan started her own company. She hired employees. She won larger contracts. She became a business owner and earned a lot of money. Those traits represent the upper-middle class. There are inconsistencies between Susan’s educational level, her occupation, and her income. In a class system, a person can work hard and have little education and still be in the middle or upper class, whereas in a caste system that would not be possible. In a class system, low-status consistency correlates with having more choices and opportunities.

SOCIAL POLICY AND DEBATE

The Commoner Who Could Be Queen

Figure 6.6 Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, who is in line to be king of England, married Catherine Middleton, a so-called commoner, meaning she does not have royal ancestry. Prince Harry married Meghan Markle, a person of mixed race. (Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

On May 19, 2018, in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in the United Kingdom, Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex, married Meghan Markle, a commoner. It is rare, though not unheard of, for a member of the British royal family to marry a commoner. Markle is the second American and the first person of mixed-race heritage to marry into the British royal family. Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and the elder brother of Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex, received similar reactions to their marriage choices. Prince William, who is in line to be King of England, married Kate Middleton, who has an upper-class background but does not have royal ancestry. Her father was a former flight dispatcher and her mother was a former flight attendant and owner of Party Pieces. According to Grace Wong’s 2011 article titled “Kate Middleton: A family business that built a princess,” “[t]he business grew to the point where [her father] quit his job . . . and it’s evolved from a mom-and-pop outfit run out of a shed . . . into a venture operated out of three converted farm buildings in Berkshire.” Kate and William met when they were both students at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland (Köhler 2010).

Britain’s monarchy arose during the Middle Ages. Its social hierarchy placed royalty at the top and commoners at the bottom. This was generally a closed system, with people born into positions of nobility. Wealth was passed from generation to generation through primogeniture, a law stating that all property would be inherited by the firstborn son. If the family had no son, the land went to the next closest male relation. Women could not inherit property, and their social standing was primarily determined through marriage.

The arrival of the Industrial Revolution changed Britain’s social structure. Commoners moved to cities, got jobs, and made better livings. Gradually, people found new opportunities to increase their wealth and power. Today, the government is a constitutional monarchy with the prime minister and other ministers elected to their positions, and the royal family’s role is largely ceremonial. The long-ago differences between nobility and commoners have blurred, and the modern class system in Britain is similar to that of the United States (McKee 1996).

Today, the royal family still commands wealth, power, and a great deal of attention. When Queen Elizabeth II retires or passes away, Prince Charles will be first in line to ascend the throne. If he abdicates (chooses not to become king) or dies, the position will go to Prince William. If that happens, Kate Middleton will be called Queen Catherine and hold the position of queen consort. She will be one of the few queens in history to have earned a college degree (Marquand 2011).

There is a great deal of social pressure on her not only to behave like a royal but also to bear children. In fact, Kate and Prince William welcomed their first son, Prince George, on July 22, 2013, and are expecting their second child. The royal family recently changed its succession laws to allow daughters, not just sons, to ascend the throne. Kate’s experience—from commoner to the potential queen—demonstrates the fluidity of social position in modern society.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the U.S. class structure

- Describe several types of social mobility

- Recognize characteristics that define and identify class

Most sociologists define social class as a grouping based on similar social factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. These factors affect how much power and prestige a person has. Social stratification reflects an unequal distribution of resources. In most cases, having more money means having more power or more opportunities. Stratification can also result from physical and intellectual traits. Categories that affect social standing include family ancestry, race, ethnicity, age, and gender. In the United States, standing can also be defined by characteristics such as IQ, athletic abilities, appearance, personal skills, and achievements.

Standard of Living

In the last century, the United States has seen a steady rise in its standard of living, the level of wealth available to a certain socioeconomic class in order to acquire the material necessities and comforts to maintain its lifestyle. The standard of living is based on factors such as income, employment, class, poverty rates, and housing affordability. Because the standard of living is closely related to the quality of life, it can represent factors such as the ability to afford a home, own a car, and take vacations.

In the United States, a small portion of the population has the means to achieve the highest standard of living. A Federal Reserve Bank study shows that a mere one percent of the population holds one-third of our nation’s wealth (Kennickell 2009). Wealthy people receive the most schooling, have better health, and consume the most goods and services. Wealthy people also wield decision-making power. Many people think of the United States as a “middle-class society.” They think a few people are rich, a few are poor, and most are fairly well off, existing in the middle of the social strata. But as the study mentioned above indicates, there is not an even distribution of wealth. Millions of women and men struggle to pay rent, buy food, find work, and afford basic medical care. Women who are single heads of households tend to have a lower income and lower standard of living than their married or male counterparts. This is a worldwide phenomenon known as the “feminization of poverty”—which acknowledges that women disproportionately make up the majority of individuals in poverty across the globe.

In the United States, as in most high-income nations, social stratifications and standards of living are in part based on occupation (Lin and Xie 1988). Aside from the obvious impact that income has on someone’s standard of living, occupations also influence social standing through the relative levels of prestige they afford. Employment in medicine, law, or engineering confers high status. Teachers and police officers are generally respected, though not considered particularly prestigious. At the other end of the scale, some of the lowest rankings apply to positions like a waitress, janitor, and bus driver.

The most significant threat to the relatively high standard of living we’re accustomed to in the United States is the decline of the middle class. The size, income, and wealth of the middle class have all been declining since the 1970s. This is occurring at a time when corporate profits have increased more than 141 percent, and CEO pay has risen by more than 298 percent (Popken 2007).

G. William Domhoff, of the University of California at Santa Cruz, reports that “In 2010, the top 1% of households (the upper class) owned 35.4% of all privately held wealth, and the next 19% (the managerial, professional, and small business stratum) had 53.5%, which means that just 20% of the people owned a remarkable 89%, leaving only 11% of the wealth for the bottom 80% (wage and salary workers)” (Domhoff 2013).

While several economic factors can be improved in the United States (inequitable distribution of income and wealth, feminization of poverty, stagnant wages for most workers while executive pay and profits soar, declining middle class), we are fortunate that the poverty experienced here is most often relative poverty and not absolute poverty. Whereas absolute poverty is deprivation so severe that it puts survival in jeopardy, relative poverty is not having the means to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country.

As a wealthy developed country, the United States has the resources to provide the basic necessities to those in need through a series of federal and state social welfare programs. The best-known of these programs is likely the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is administered by the United States Department of Agriculture. (This used to be known as the food stamp program.)

The program began in the Great Depression when unmarketable or surplus food was distributed to the hungry. It was not until 1961 that President John F. Kennedy initiated a food stamp pilot program. His successor Lyndon B. Johnson was instrumental in the passage of the Food Stamp Act in 1964. In 1965, more than 500,000 individuals received food assistance. In March 2008, on the precipice of the Great Recession, participation hovered around 28 million people. During the recession, that number escalated to more than 40 million (USDA).

Social Classes in the United States

Does a person’s appearance indicate class? Can you tell a man’s education level based on his clothing? Do you know a woman’s income by the car she drives?

For sociologists, categorizing class is a fluid science. Sociologists generally identify three levels of class in the United States: upper, middle, and lower class. Within each class, there are many subcategories. Wealth is the most significant way of distinguishing classes because wealth can be transferred to one’s children and perpetuate the class structure. One economist, J.D. Foster, defines the 20 percent of U.S. citizens’ highest earners as “upper income,” and the lower 20 percent as “lower income.” The remaining 60 percent of the population makes up the middle class. But by that distinction, annual household incomes for the middle-class range between $25,000 and $100,000 (Mason and Sullivan 2010).

One sociological perspective distinguishes the classes, in part, according to their relative power and control over their lives. The upper class not only has power and control over their own lives but also their social status gives them power and control over others’ lives. The middle class doesn’t generally control other strata of society, but its members do exert control over their own lives. In contrast, the lower class has little control over their work or lives. Below, we will explore the major divisions of U.S. social class and their key subcategories.

The Upper Class

The upper class is considered the top, and only the powerful elite get to see the view from there. In the United States, people with extreme wealth make up 1 percent of the population, and they own one-third of the country’s wealth (Beeghley 2008).

Money provides not just access to material goods but also access to a lot of power. As corporate leaders, members of the upper class make decisions that affect the job status of millions of people. As media owners, they influence the collective identity of the nation. They run the major network television stations, radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, and sports franchises. As board members of the most influential colleges and universities, they influence cultural attitudes and values. As philanthropists, they establish foundations to support social causes they believe in. As campaign contributors, they sway politicians and fund campaigns, sometimes to protect their own economic interests.

U.S. society has historically distinguished between “old money” (inherited wealth passed from one generation to the next) and “new money” (wealth you have earned and built yourself). While both types may have equal net worth, they have traditionally held different social standings. People of old money, firmly situated in the upper class for generations, have held high prestige. Their families have socialized them to know the customs, norms, and expectations that come with wealth. Often, the very wealthy don’t work for wages. Some study business or become lawyers in order to manage the family fortune. Others, such as Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian, capitalize on being a rich socialite and transform that into celebrity status, flaunting a wealthy lifestyle.

However, new-money members of the upper class are not oriented to the customs and mores of the elite. They haven’t gone to the most exclusive schools. They have not established old-money social ties. People with new money might flaunt their wealth, buying sports cars and mansions, but they might still exhibit behaviors attributed to the middle and lower classes.

The Middle Class

Many people consider themselves middle class, but there are differing ideas about what that means. People with annual incomes of $150,000 call themselves middle class, as do people who annually earn $30,000. That helps explain why, in the United States, the middle class is broken into upper and lower subcategories.

Upper-middle-class people tend to hold bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees. They’ve studied subjects such as business, management, law, and medicine. Lower-middle-class members hold bachelor’s degrees from four-year colleges or associate’s degrees from a two-year community or technical colleges.

Comfort is a key concept to the middle class. Middle-class people work hard and live fairly comfortable lives. Upper-middle-class people tend to pursue careers that earn comfortable incomes. They provide their families with large homes and nice cars. They may go skiing or boating on vacation. Their children receive high-quality education and healthcare (Gilbert 2010).

In the lower-middle class, people hold jobs supervised by members of the upper-middle class. They fill technical, lower-level management, or administrative support positions. Compared to lower-class work, lower-middle-class jobs carry more prestige and come with slightly higher paychecks. With these incomes, people can afford a decent, mainstream lifestyle, but they struggle to maintain it. They generally don’t have enough income to build significant savings. In addition, their grip on class status is more precarious than in the upper tiers of the class system. When budgets are tight, lower-middle-class people are often the ones to lose their jobs.

The Lower Class

The lower class is also referred to as the working class. Just like the middle and upper classes, the lower class can be divided into subsets: the working class, the working poor, and the underclass. Compared to the lower-middle class, lower-class people have less educational background and earn smaller incomes. They work jobs that require little prior skill or experience and often do routine tasks under close supervision.

Working-class people, the highest subcategory of the lower class, often land decent jobs in fields like custodial or food service. The work is hands-on and often physically demanding, such as landscaping, cooking, cleaning, or building.

Beneath the working class is the working poor. Like the working class, they have unskilled, low-paying employment. However, their jobs rarely offer benefits such as healthcare or retirement planning, and their positions are often seasonal or temporary. They work as sharecroppers, migrant farmworkers, housecleaners, and day laborers. Some are high school dropouts. Some are illiterate and unable to read job ads.

How can people work full-time and still be poor? Even working full-time, millions of the working poor earn incomes too meager to support a family. The minimum wage varies from state to state, but in many states, it is approaching $8.00 per hour (Department of Labor 2014). At that rate, working 40 hours a week earns $320. That comes to $16,640 a year, before tax and deductions. Even for a single person, the pay is low. A married couple with children will have a hard time covering expenses.

The underclass is the United States’ lowest tier. Members of the underclass live mainly in inner cities. Many are unemployed or underemployed. Those who do hold jobs typically perform menial tasks for little pay. Some of the underclasses are homeless. For many, welfare systems provide much-needed support through food assistance, medical care, housing, and the like.

Social Mobility

Social mobility refers to the ability to change positions within a social stratification system. When people improve or diminish their economic status in a way that affects social class, they experience social mobility.

Individuals can experience upward or downward social mobility for a variety of reasons. Upward mobility refers to an increase—or upward shift—in social class. In the United States, people applaud the rags-to-riches achievements of celebrities like Jennifer Lopez or Michael Jordan. Bestselling author Stephen King worked as a janitor prior to being published. Oprah Winfrey grew up in poverty in rural Mississippi before becoming a powerful media personality. There are many stories of people rising from modest beginnings to fame and fortune. But the truth is that relative to the overall population, the number of people who rise from poverty to wealth is very small. Still, upward mobility is not only about becoming rich and famous. In the United States, people who earn a college degree, get a job promotion, or marry someone with a good income may move up socially. In contrast, downward mobility indicates a lowering of one’s social class. Some people move downward because of business setbacks, unemployment, or illness. Dropping out of school, losing a job, or getting a divorce may result in a loss of income or status and, therefore, downward social mobility.

It is not uncommon for different generations of a family to belong to varying social classes. This is known as intergenerational mobility. For example, an upper-class executive may have parents who belonged to the middle class. In turn, those parents may have been raised in the lower class. Patterns of intergenerational mobility can reflect long-term societal changes.

Similarly, intragenerational mobility refers to changes in a person’s social mobility over the course of his or her lifetime. For example, the wealth and prestige experienced by one person may be quite different from that of his or her siblings.

Structural mobility happens when societal changes enable a whole group of people to move up or down the social class ladder. Structural mobility is attributable to changes in society as a whole, not individual changes. In the first half of the twentieth century, industrialization expanded the U.S. economy, raising the standard of living and leading to upward structural mobility. In today’s work economy, the recent recession and the outsourcing of jobs overseas have contributed to high unemployment rates. Many people have experienced economic setbacks, creating a wave of downward structural mobility.

When analyzing the trends and movements in social mobility, sociologists consider all modes of mobility. Scholars recognize that mobility is not as common or easy to achieve as many people think. In fact, some consider social mobility a myth.

Class Traits

Class traits, also called class markers, are the typical behaviors, customs, and norms that define each class. Class traits indicate the level of exposure a person has to a wide range of cultures. Class traits also indicate the number of resources a person has to spend on items like hobbies, vacations, and leisure activities.

People may associate the upper class with the enjoyment of costly, refined, or highly cultivated tastes—expensive clothing, luxury cars, high-end fundraisers, and opulent vacations. People may also believe that the middle and lower classes are more likely to enjoy camping, fishing, or hunting; shopping at large retailers; and participating in community activities. While these descriptions may identify class traits, they may also simply be stereotypes. Moreover, just as class distinctions have blurred in recent decades, so too have class traits. A very wealthy person may enjoy bowling as much as opera. A factory worker could be a skilled French cook. A billionaire might dress in ripped jeans, and a low-income student might own designer shoes.

SOCIOLOGICAL RESEARCH

Turn-of-the-Century “Social Problem Novels”: Sociological Gold Mines

Class distinctions were sharper in the nineteenth century and earlier, in part because people easily accepted them. The ideology of social order made class structure seem natural, right, and just.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, U.S. and British novelists played a role in changing public perception. They published novels in which characters struggled to survive against a merciless class system. These dissenting authors used gender and morality to question the class system and expose its inequalities. They protested the suffering of urbanization and industrialization, drawing attention to these issues.

These “social problem novels,” sometimes called Victorian realism, forced middle-class readers into an uncomfortable position: they had to question and challenge the natural order of social class.

For speaking out so strongly about the social issues of class, authors were both praised and criticized. Most authors did not want to dissolve the class system. They wanted to bring about an awareness that would improve conditions for the lower classes while maintaining their own higher class positions (DeVine 2005).

Soon, middle-class readers were not their only audience. In 1870, Forster’s Elementary Education Act required all children ages five through twelve in England and Wales to attend school. The act increased literacy levels among the urban poor, causing a rise in sales of cheap newspapers and magazines. The increasing number of people who rode public transit systems created a demand for “railway literature,” as it was called (Williams 1984). These reading materials are credited with the move toward democratization in England. By 1900 the British middle class had established a rigid definition for itself, and England’s working-class also began to self-identify and demand a better way of life.

Many of the novels of that era are seen as sociological goldmines. They are studied as existing sources because they detail the customs and mores of the upper, middle, and lower classes of that period in history.

Examples of “social problem” novels include Charles Dickens’s The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1838), which shocked readers with its brutal portrayal of the realities of poverty, vice, and crime. Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) was considered revolutionary by critics for its depiction of working-class women (DeVine 2005), and U.S. novelist Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900) portrayed an accurate and detailed description of early Chicago.

Learning Objectives

- Define global stratification

- Describe different sociological models for understanding global stratification

- Understand how studies of global stratification identify worldwide inequalities

Global stratification compares the wealth, economic stability, status, and power of countries across the world. Global stratification highlights worldwide patterns of social inequality.

In the early years of civilization, hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies lived off the earth and rarely interacted with other societies. When explorers began traveling, societies began trading goods, as well as ideas and customs.

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution created unprecedented wealth in Western Europe and North America. Due to mechanical inventions and new means of production, people began working in factories—not only men but women and children as well. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, industrial technology had gradually raised the standard of living for many people in the United States and Europe.

The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of vast inequalities between countries that were industrialized and those that were not. As some nations embraced technology and saw increased wealth and goods, others maintained their ways; as the gap widened, the nonindustrialized nations fell further behind. Some social researchers, such as Walt Rostow, suggest that the disparity also resulted from power differences. Applying a conflict theory perspective, he asserts that industrializing nations took advantage of the resources of traditional nations. As industrialized nations became rich, other nations became poor (Rostow 1960).

Sociologists studying global stratification analyze economic comparisons between nations. Income, purchasing power, and wealth are used to calculate global stratification. Global stratification also compares the quality of life that a country’s population can have.

Poverty levels have been shown to vary greatly. The poor in wealthy countries like the United States or Europe are much better off than the poor in less-industrialized countries such as Mali or India. In 2002, the UN implemented the Millennium Project, an attempt to cut poverty worldwide by the year 2015. To reach the project’s goal, planners in 2006 estimated that industrialized nations must set aside 0.7 percent of their gross national income—the total value of the nation’s goods and services, plus or minus income received from and sent to other nations—to aid in developing countries (Landler and Sanger, 2009; Millennium Project 2006).

Models of Global Stratification

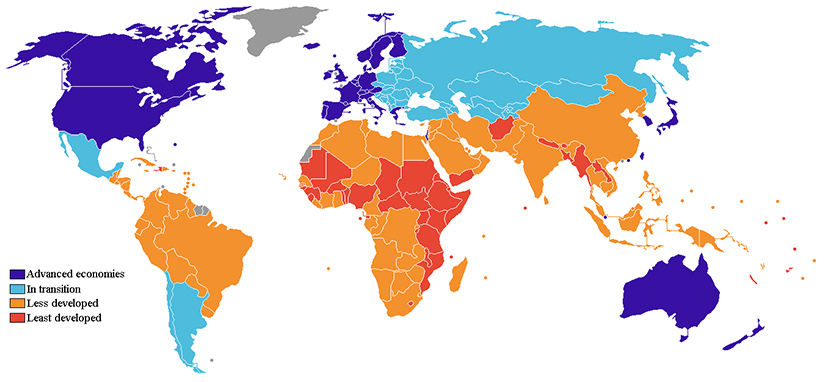

Various models of global stratification all have one thing in common: they rank countries according to their relative economic status, or gross national product (GNP). Traditional models, now considered outdated, used labels to describe the stratification of the different areas of the world. Simply put, they were named “first world,” “second world,” and “third world.” The first and second world described industrialized nations, while the third world referred to “undeveloped” countries (Henslin 2004). When researching existing historical sources, you may still encounter these terms, and even today people still refer to some nations as the “third world.”

Another model separates countries into two groups: more developed and less developed. More-developed nations have higher wealth, such as Canada, Japan, and Australia. Less-developed nations have less wealth to distribute among higher populations, including many countries in central Africa, South America, and some island nations.

Yet another system of global classification defines countries based on the per capita gross domestic product (GDP), a country’s average national wealth per person. The GDP is calculated (usually annually) in one of two ways: by totaling either the income of all citizens or the value of all goods and services produced in the country during the year. It also includes government spending. Because the GDP indicates a country’s productivity and performance, comparing GDP rates helps establish a country’s economic health in relation to other countries.

The figures also establish a country’s standard of living. According to this analysis, the GDP standard of a middle-income nation represents a global average. In low-income countries, most people are poor relative to people in other countries. Citizens have little access to amenities such as electricity, plumbing, and clean water. People in low-income countries are not guaranteed education, and many are illiterate. The life expectancy of citizens is lower than in high-income countries.

BIG PICTURE

Calculating Global Stratification

A few organizations take on the job of comparing the wealth of nations. The Population Reference Bureau (PRB) is one of them. Besides having a focus on population data, the PRB publishes an annual report that measures the relative economic well-being of all the world’s countries. It’s called the Gross National Income (GNI) and Purchasing Power Parity (PPP).

The GNI measures the current value of goods and services produced by a country. The PPP measures the relative power a country has to purchase those same goods and services. So, GNI refers to productive output and PPP refers to buying power. The total figure is divided by the number of residents living in a country to establish the average income of a resident of that country.

Because the costs of goods and services vary from one country to the next, the GNI PPP converts figures into a relative international unit. Calculating GNI PPP figures helps researchers accurately compare countries’ standards of living. They allow the United Nations and Population Reference Bureau to compare and rank the wealth of all countries and consider international stratification issues (nationsonline.org).

Learning Objectives

- Understand and apply functionalist, conflict theory, and interactionist perspectives on social stratification

Basketball is one of the highest-paying professional sports. There is stratification even among teams. For example, the Minnesota Timberwolves hand out the lowest annual payroll, while the Los Angeles Lakers reportedly pay the highest. Kobe Bryant, a former Lakers shooting guard, was one of the highest-paid athletes in the NBA, earning around $30.5 million a year (Forbes 2014). Even within specific fields, layers are stratified and members are ranked.

In sociology, even an issue such as NBA salaries can be seen from various points of view. Functionalists will examine the purpose of such high salaries, while conflict theorists will study the exorbitant salaries as an unfair distribution of money. Social stratification takes on new meanings when it is examined from different sociological perspectives—functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

Functionalism

In sociology, the functionalist perspective examines how society’s parts operate. According to functionalism, different aspects of society exist because they serve a needed purpose. What is the function of social stratification?

In 1945, sociologists Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore published the Davis-Moore thesis, which argued that the greater the functional importance of a social role, the greater must be the reward. The theory posits that social stratification represents the inherently unequal value of different work. Certain tasks in society are more valuable than others. Qualified people who fill those positions must be rewarded more than others.

According to Davis and Moore, a firefighter’s job is more important than, for instance, a grocery store cashier’s. The cashier position does not require the same skill and training level as firefighting. Without the incentive of higher pay and better benefits, why would someone be willing to rush into burning buildings? If pay levels were the same, the firefighter might as well work as a grocery store cashier. Davis and Moore believed that rewarding more important work with higher levels of income, prestige, and power encourages people to work harder and longer.

Davis and Moore stated that, in most cases, the degree of skill required for a job determines that job’s importance. They also stated that the more skill required for a job, the fewer qualified people there would be to do that job. Certain jobs, such as cleaning hallways or answering phones, do not require much skill. The employees don’t need a college degree. Other work, like designing a highway system or delivering a baby, requires immense skill.

In 1953, Melvin Tumin countered the Davis-Moore thesis in “Some Principles of Stratification: A Critical Analysis.” Tumin questioned what determined a job’s degree of importance. The Davis-Moore thesis does not explain, he argued, why a media personality with little education, skill, or talent becomes famous and rich on a reality show or a campaign trail. The thesis also does not explain inequalities in the education system or inequalities due to race or gender. Tumin believed social stratification prevented qualified people from attempting to fill roles (Tumin 1953). For example, an underprivileged youth has less chance of becoming a scientist, no matter how smart she is, because of the relative lack of opportunity available to her. The Davis-Moore thesis also does not explain why a basketball player earns millions of dollars a year when a doctor who saves lives, a soldier who fights for others’ rights, and a teacher who helps form the minds of tomorrow will likely not make millions over the course of their careers.

The Davis-Moore thesis, though open for debate, was an early attempt to explain why stratification exists. The thesis states that social stratification is necessary to promote excellence, productivity, and efficiency, thus giving people something to strive for. Davis and Moore believed that the system serves society as a whole because it allows everyone to benefit to a certain extent.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists are deeply critical of social stratification, asserting that it benefits only some people, not all of society. For instance, to a conflict theorist, it seems wrong that a basketball player is paid millions for an annual contract while a public school teacher earns $35,000 a year. Stratification, conflict theorists believe, perpetuates inequality. Conflict theorists try to bring awareness to inequalities, such as how a rich society can have so many poor members.

Many conflict theorists draw on the work of Karl Marx. During the nineteenth-century era of industrialization, Marx believed social stratification resulted from people’s relationship to production. People were divided by a single line: they either owned factories or worked in them. In Marx’s time, bourgeois capitalists owned high-producing businesses, factories, and land, as they still do today. Proletariats were the workers who performed manual labor to produce goods. Upper-class capitalists raked in profits and got rich, while working-class proletariats earned skimpy wages and struggled to survive. With such opposing interests, the two groups were divided by differences in wealth and power. Marx saw workers experience deep alienation, isolation, and misery resulting from powerless status levels (Marx 1848). Marx argued that proletariats were oppressed by the money-hungry bourgeois.

Today, while working conditions have improved, conflict theorists believe that the strained working relationship between employers and employees still exists. Capitalists own the means of production, and a system is in place to make business owners rich and keep workers poor. According to conflict theorists, the resulting stratification creates class conflict. If he were alive in today’s economy, as it recovers from a prolonged recession, Marx would likely have argued that the recession resulted from the greed of capitalists, satisfied at the expense of working people.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a theory that uses the everyday interactions of individuals to explain society as a whole. Symbolic interactionism examines stratification from a micro-level perspective. This analysis strives to explain how people’s social standing affects their everyday interactions.

In most communities, people interact primarily with others who share the same social standing. It is precisely because of social stratification that people tend to live, work, and associate with others like themselves, people who share the same income level, educational background, or racial background, and even tastes in food, music, and clothing. The built-in system of social stratification groups people together. This is one of the reasons why it was rare for a royal prince like England’s Prince William to marry a commoner.

Symbolic interactionists also note that people’s appearance reflects their perceived social standing. Housing, clothing, and transportation indicate social status, as do hairstyles, taste in accessories, and personal style.

To symbolically communicate social standing, people often engage in conspicuous consumption, which is the purchase and use of certain products to make a social statement about status. Carrying pricey but eco-friendly water bottles could indicate a person’s social standing. Some people buy expensive trendy sneakers even though they will never wear them to jog or play sports. A $17,000 car provides transportation as easily as a $100,000 vehicle, but the luxury car makes a social statement that the less expensive car can’t live up to. All these symbols of stratification are worthy of examination by interactions.

Introduction to Global Inequality

The April 24, 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza in Dhaka, Bangladesh which killed over 1,100 people, was the deadliest garment factory accident in history, and it was preventable (International Labour Organization, Department of Communication 2014).

In addition to garment factories employing about 5,000 people, the building contained a bank, apartments, childcare facilities, and a variety of shops. Many of these closed the day before the collapse when cracks were discovered in the building walls. When some of the garment workers refused to enter the building, they were threatened with the loss of a month’s pay. Most were young women, aged twenty or younger. They typically worked over thirteen hours a day, with two days off each month. For this work, they took home between twelve and twenty-two cents an hour, or $10.56 to $12.48 a week. Without that pay, most would have been unable to feed their children. In contrast, the U.S. federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, and workers receive wages at time-and-a-half rates for work in excess of forty hours a week.

Did you buy clothes from Walmart in 2012? What about at The Children’s Place? Did you ever think about where those clothes came from? Of the outsourced garments made in the garment factories, 32 percent were intended for U.S., Canadian, and European stores. In the aftermath of the collapse, it was revealed that Walmart jeans were made in the Ether Tex garment factory on the fifth floor of the Rana Plaza building, while 120,000 pounds of clothing for The Children’s Place were produced in the New Wave Style Factory, also located in the building. Afterward, Walmart and The Children’s Place pledged $1 million and $450,000 (respectively) to the Rana Plaza Trust Fund, but fifteen other companies with clothing made in the building have contributed nothing, including U.S. companies Cato and J.C. Penney (Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights 2014).

While you read this chapter, think about the global system that allows U.S. companies to outsource their manufacturing to peripheral nations, where many women and children work in conditions that some characterize as slave labor. Do people in the United States have a responsibility to foreign workers? Should U.S. corporations be held accountable for what happens to garment factory workers who make their clothing? What can you do as a consumer to help such workers?

Learning Objectives

- Describe global stratification

- Understand how different classification systems have developed

- Use terminology from Wallerstein’s world-systems approach

- Explain the World Bank’s classification of economies

Just as the United States’ wealth is increasingly concentrated among its richest citizens while the middle class slowly disappears, global inequality is concentrating resources in certain nations and is significantly affecting the opportunities of individuals in poorer and less powerful countries. In fact, a recent Oxfam (2014) report that suggested the richest eighty-five people in the world are worth more than the poorest 3.5 billion combined. The Gini coefficient measures income inequality between countries using a 100-point scale on which 1 represents complete equality and 100 represents the highest possible inequality. In 2007, the global Gini coefficient that measured the wealth gap between the core nations in the northern part of the world and the most peripheral nations in the southern part of the world was 75.5 percent (Korseniewicz and Moran 2009). But before we delve into the complexities of global inequality, let’s consider how the three major sociological perspectives might contribute to our understanding of it.

The functionalist perspective is a macro analytical view that focuses on the way that all aspects of society are integral to the continued health and viability of the whole. A functionalist might focus on why we have global inequality and what social purposes it serves. This view might assert, for example, that we have global inequality because some nations are better than others at adapting to new technologies and profiting from a globalized economy, and that when core nation companies locate in peripheral nations, they expand the local economy and benefit the workers.

Conflict theory focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality. A conflict theorist would likely address the systematic inequality created when core nations exploit the resources of peripheral nations. For example, how many U.S. companies take advantage of overseas workers who lack the constitutional protection and guaranteed minimum wages that exist in the United States? Doing so allows them to maximize profits, but at what cost?

The symbolic interaction perspective studies the day-to-day impact of global inequality, the meanings individuals attach to global stratification, and the subjective nature of poverty. Someone applying this view to global inequality would probably focus on understanding the difference between what someone living in a core nation defines as poverty (relative poverty, defined as being unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country) and what someone living in a peripheral nation defines as poverty (absolute poverty, defined as being barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities, such as food).

Global Stratification

While stratification in the United States refers to the unequal distribution of resources among individuals, global stratification refers to this unequal distribution among nations. There are two dimensions to this stratification: gaps between nations and gaps within nations. When it comes to global inequality, both economic inequality and social inequality may concentrate the burden of poverty among certain segments of the earth’s population (Myrdal 1970). As the chart below illustrates, people’s life expectancy depends heavily on where they happen to be born.

| Country | Infant Mortality Rate | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|

| Norway | 2.48 deaths per 1000 live births | 81 years |

| United States | 6.17 deaths per 1000 live births | 79 years |

| North Korea | 24.50 deaths per 1000 live births | 70 years |

| Afghanistan | 117.3 deaths per 1000 live births | 50 years |

Most of us are accustomed to thinking of global stratification as economic inequality. For example, we can compare the United States’ average worker’s wage to America’s average wage. Social inequality, however, is just as harmful as economic discrepancies. Prejudice and discrimination—whether against a certain race, ethnicity, religion, or the like—can create and aggravate conditions of economic equality, both within and between nations. Think about the inequity that existed for decades within the nation of South Africa. Apartheid, one of the most extreme cases of institutionalized and legal racism, created a social inequality that earned it the world’s condemnation.

Gender inequity is another global concern. Consider the controversy surrounding female genital mutilation. Nations that practice this female circumcision procedure defend it as a longstanding cultural tradition in certain tribes and argue that the West shouldn’t interfere. Western nations, however, decry the practice and are working to stop it.

Inequalities based on sexual orientation and gender identity exist around the globe. According to Amnesty International, a number of crimes are committed against individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles or sexual orientations (however those are culturally defined). From culturally sanctioned rape to state-sanctioned executions, the abuses are serious. These legalized and culturally accepted forms of prejudice and discrimination exist everywhere—from the United States to Somalia to Tibet—restricting the freedom of individuals and often putting their lives at risk (Amnesty International 2012).

Global Classification

A major concern when discussing global inequality is how to avoid an ethnocentric bias implying that less-developed nations want to be like those who’ve attained post-industrial global power. Terms such as developing (nonindustrialized) and developed (industrialized) imply that unindustrialized countries are somehow inferior and must improve to participate successfully in the global economy, a label indicating all aspects of the economy across national borders. We must take care in how we delineate different countries. Over time, the terminology has shifted to make way for a more inclusive view of the world.

Cold War Terminology

Cold War terminology was developed during the Cold War era (1945–1980). Familiar and still used by many, it classifies countries as first-world, second-world, and third-world nations based on their respective economic development and standards of living. When this nomenclature was developed, capitalistic democracies such as the United States and Japan were considered part of the first world. The poorest, most undeveloped countries were referred to as the third world and included most of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The second world was the in-between category: nations not as limited in development as the third world but not as well off as the first world, having moderate economies and standards of living, such as China or Cuba. Later, sociologist Manual Castells (1998) added the term fourth world to refer to stigmatized minority groups that were denied a political voice all over the globe (indigenous minority populations, prisoners, and the homeless, for example).

Also during the Cold War, global inequality was described in terms of economic development. Along with developing and developed nations, the terms less-developed nation and underdeveloped nation were used. This was the era when the idea of noblesse oblige (first-world responsibility) took root, suggesting that the so-termed developed nations should provide foreign aid to the less-developed and underdeveloped nations in order to raise their standard of living.

Immanuel Wallerstein: World Systems Approach

Immanuel Wallerstein’s (1979) world systems approach uses an economic basis to understand global inequality. Wallerstein conceived of the global economy as a complex system that supports an economic hierarchy that places some nations in positions of power with numerous resources and other nations in a state of economic subordination. Those that are in a state of subordination face significant obstacles to mobilization.

Core nations are dominant capitalist countries, highly industrialized, technological, and urbanized. For example, Wallerstein contends that the United States is an economic powerhouse that can support or deny support to important economic legislation with far-reaching implications, thus exerting control over every aspect of the global economy and exploiting both semi-peripheral and peripheral nations. We can look at free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as an example of how a core nation is able to leverage its power to gain the most advantageous position in the matter of global trade.

Peripheral nations have very little industrialization; what they do have often represents the outdated castoffs of core nations or the factories and means of production owned by core nations. They typically have unstable governments and inadequate social programs, and they are economically dependent on core nations for jobs and aid. There are abundant examples of countries in this category, such as Vietnam and Cuba. We can be sure the workers in a Cuban cigar factory, for example, which is owned or leased by global core nation companies, are not enjoying the same privileges and rights as U.S. workers.

Semi-peripheral nations are in-between nations, not powerful enough to dictate policy but nevertheless acting as a major source of raw material and an expanding middle-class marketplace for core nations, while also exploiting peripheral nations. Mexico is an example, providing abundant cheap agricultural labor to the U.S. and supplying goods to the United States market at a rate dictated by the U.S. without the constitutional protections offered to United States workers.

World Bank Economic Classification by Income

While the World Bank is often criticized, both for its policies and its method of calculating data, it is still a common source of global economic data. Along with tracking the economy, the World Bank tracks demographics and environmental health to provide a complete picture of whether a nation is high income, middle income, or low income.

High-Income Nations

The World Bank defines high-income nations as having a gross national income of at least $12,746 per capita. The OECD (Organization for Economic and Cooperative Development) countries make up a group of thirty-four nations whose governments work together to promote economic growth and sustainability. According to the World Bank (2014b), in 2013, the average gross national income (GNI) per capita (or the mean income of the people in a nation, found by dividing the total GNI by the total population) of a high-income nation belonging to the OECD was $43,903 per capita and the total population was over one billion (1.045 billion); on average, 81 percent of the population in these nations was urban. Some of these countries include the United States, Germany, Canada, and the United Kingdom (World Bank 2014b).

High-income countries face two major issues: capital flight and deindustrialization. Capital flight refers to the movement (flight) of capital from one nation to another, as when General Motors automotive company closed U.S. factories in Michigan and opened factories in Mexico. Deindustrialization, a related issue, occurs as a consequence of capital flight, as no new companies open to replace jobs lost to foreign nations. As expected, global companies move their industrial processes to the places where they can get the most production with the least cost, including the building of infrastructure, training of workers, shipping of goods, and, of course, paying employee wages. This means that as emerging economies create their own industrial zones, global companies see the opportunity for existing infrastructure and much lower costs. Those opportunities lead to businesses closing the factories that provide jobs to the middle class within core nations and moving their industrial production to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations.

BIG PICTURE

Capital Flight, Outsourcing, and Jobs in the United States

Capital flight describes jobs and infrastructure moving from one nation to another. Look at the U.S. automobile industry. In the early twentieth century, the cars driven in the United States were made here, employing thousands of workers in Detroit and in the companies that produced everything that made building cars possible. However, once the fuel crisis of the 1970s hit and people in the United States increasingly looked to imported cars with better gas mileage, U.S. auto manufacturing began to decline. During the 2007–2009 recession, the U.S. government bailed out the three main auto companies, underscoring their vulnerability. At the same time, Japanese-owned Toyota and Honda and South Korean Kia maintained stable sales levels.

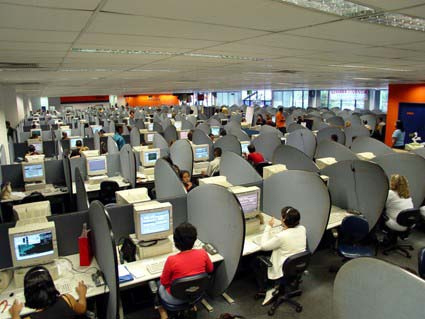

Capital flight also occurs when services (as opposed to manufacturing) are relocated. Chances are if you have called the tech support line for your cell phone or Internet provider, you’ve spoken to someone halfway across the globe. This professional might tell you her name is Susan or Joan, but her accent makes it clear that her real name might be Parvati or Indira. It might be the middle of the night in that country, yet these service providers pick up the line saying, “Good morning,” as though they are in the next town over. They know everything about your phone or your modem, often using a remote server to log in to your home computer to accomplish what is needed. These are the workers of the twenty-first century. They are not on factory floors or in traditional sweatshops; they are educated, speak at least two languages, and usually have significant technical skills. They are skilled workers, but they are paid a fraction of what similar workers are paid in the United States. For U.S. and multinational companies, the equation makes sense. India and other semi-peripheral countries have emerging infrastructures and education systems to fill their needs, without core nation costs.

As services are relocated, so are jobs. In the United States, unemployment is high. Many college-educated people are unable to find work, and those with only a high school diploma are in even worse shape. We have, as a country, outsourced ourselves out of jobs, and not just menial jobs, but white-collar work as well. But before we complain too bitterly, we must look at the culture of consumerism that we embrace. A flat-screen television that might have cost $1,000 a few years ago is now $350. That cost-saving has to come from somewhere. When consumers seek the lowest possible price, shop at big box stores for the biggest discount they can get, and generally ignore other factors in exchange for low cost, they are building the market for outsourcing. And as the demand is built, the market will ensure it is met, even at the expense of the people who wanted it in the first place.

Middle-Income Nations

The World Bank defines middle-income economies as those with a GNI per capita of more than $1,045 but less than $12,746. According to the World Bank (2014), in 2013, the average GNI per capita of an upper-middle-income nation was $7,594 per capita with a total population of 2.049 billion, of which 62 percent was urban. Thailand, China, and Namibia are examples of middle-income nations (World Bank 2014a).

Perhaps the most pressing issue for middle-income nations is the problem of debt accumulation. As the name suggests, debt accumulation is the buildup of external debt, wherein countries borrow money from other nations to fund their expansion or growth goals. As the uncertainties of the global economy make repaying these debts, or even paying the interest on them, more challenging, nations can find themselves in trouble. Once global markets have reduced the value of a country’s goods, it can be very difficult to ever manage the debt burden. Such issues have plagued middle-income countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as East Asian and Pacific nations (Dogruel and Dogruel 2007). By way of example, even in the European Union, which is composed of more core nations than semi-peripheral nations, the semi-peripheral nations of Italy and Greece face increasing debt burdens. The economic downturns in both Greece and Italy still threaten the economy of the entire European Union.

Low-Income Nations

The World Bank defines low-income countries as nations whose per capita GNI was $1,045 per capita or less in 2013. According to the World Bank (2014a), in 2013, the average per capita GNI of a low-income nation was $528 per capita and the total population was 796,261,360, with 28 percent located in urban areas. For example, Myanmar, Ethiopia, and Somalia are considered low-income countries. Low-income economies are primarily found in Asia and Africa (World Bank 2014a), where most of the world’s population lives. There are two major challenges that these countries face: women are disproportionately affected by poverty (in a trend toward a global feminization of poverty), and much of the population lives in absolute poverty.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the differences between relative, absolute, and subjective poverty

- Describe the economic situation of some of the world’s most impoverished areas

- Explain the cyclical impact of the consequences of poverty

What does it mean to be poor? Does it mean being a single mother with two kids in New York City, waiting for the next paycheck in order to buy groceries? Does it mean living with almost no furniture in your apartment because your income doesn’t allow for extras like beds or chairs? Or does it mean having to live with the distended bellies of the chronically malnourished throughout the peripheral nations of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia? Poverty has a thousand faces and a thousand gradations; there is no single definition that pulls together every part of the spectrum. You might feel you are poor if you can’t afford cable television or buy your own car. Every time you see a fellow student with a new laptop and smartphone you might feel that you, with your ten-year-old desktop computer, are barely keeping up. However, someone else might look at the clothes you wear and the calories you consume and consider you rich.

Types of Poverty

Social scientists define global poverty in different ways and take into account the complexities and the issues of relativism described above. Relative poverty is a state of living where people can afford necessities but are unable to meet their society’s average standard of living. People often disparage “keeping up with the Joneses”—the idea that you must keep up with the neighbors’ standard of living to not feel deprived. But it is true that you might feel “poor” if you are living without a car to drive to and from work, without any money for a safety net should a family member fall ill, and without any “extras” beyond just making ends meet.

Contrary to relative poverty, people who live in absolute poverty lack even the basic necessities, which typically include adequate food, clean water, safe housing, and access to healthcare. Absolute poverty is defined by the World Bank (2014a) as when someone lives on less than $1.25 a day. According to the most recent estimates, in 2011, about 17 percent of people in the developing world lived at or below $1.25 a day, a decrease of 26 percent compared to ten years ago, and an overall decrease of 35 percent compared to twenty years ago. A shocking number of people––88 million––live in absolute poverty, and close to 3 billion people live on less than $2.50 a day (Shah 2011). If you were forced to live on $2.50 a day, how would you do it? What would you deem worthy of spending money on, and what could you do without? How would you manage the necessities—and how would you make up the gap between what you need to live and what you can afford?

Subjective poverty describes poverty that is composed of many dimensions; it is subjectively present when your actual income does not meet your expectations and perceptions. With the concept of subjective poverty, the poor themselves have a greater say in recognizing when it is present. In short, subjective poverty has more to do with how a person or a family defines themselves. This means that a family subsisting on a few dollars a day in Nepal might think of themselves as doing well, within their perception of normal. However, a westerner traveling to Nepal might visit the same family and see an extreme need.

BIG PICTURE

The Underground Economy Around the World

What do the driver of an unlicensed hack cab in New York, a piecework seamstress working from her home in Mumbai, and a street tortilla vendor in Mexico City have in common? They are all members of the underground economy, a loosely defined unregulated market unhindered by taxes, government permits, or human protections. Official statistics before the worldwide recession posit that the underground economy accounted for over 50 percent of nonagricultural work in Latin America; the figure went as high as 80 percent in parts of Asia and Africa (Chen 2001). A recent article in the Wall Street Journal discusses the challenges, parameters, and surprising benefits of this informal marketplace. The wages earned in most underground economy jobs, especially in peripheral nations, are a pittance––a few rupees for a handmade bracelet at a market, or maybe 250 rupees ($5 U.S.) for a day’s worth of fruit and vegetable sales (Barta 2009). But these tiny sums mark the difference between survival and extinction for the world’s poor.

The underground economy has never been viewed very positively by global economists. After all, its members don’t pay taxes, don’t take out loans to grow their businesses, and rarely earn enough to put money back into the economy in the form of consumer spending. But according to the International Labor Organization (an agency of the United Nations), some 52 million people worldwide will lose their jobs due to the ongoing worldwide recession. And while those in core nations know that high unemployment rates and limited government safety nets can be frightening, their situation is nothing compared to the loss of a job for those barely eking out an existence. Once that job disappears, the chance of staying afloat is very slim.

Within the context of this recession, some see the underground economy as a key player in keeping people alive. Indeed, an economist at the World Bank credits jobs created by the informal economy as a primary reason why peripheral nations are not in worse shape during this recession. Women in particular benefit from the informal sector. The majority of economically active women in peripheral nations are engaged in the informal sector, which is somewhat buffered from the economic downturn. The flip side, of course, is that it is equally buffered by the possibility of economic growth.

Even in the United States, the informal economy exists, although not on the same scale as in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. It might include under-the-table nannies, gardeners, and housecleaners, as well as unlicensed street vendors and taxi drivers. There are also those who run informal businesses, like daycares or salons, from their houses. Analysts estimate that this type of labor may make up 10 percent of the overall U.S. economy, a number that will likely grow as companies reduce headcounts, leaving more workers to seek other options. In the end, the article suggests that, whether selling medicinal wines in Thailand or woven bracelets in India, the workers of the underground economy at least have what most people want most of all: a chance to stay afloat (Barta 2009).

Who Are the Impoverished?

Who are the impoverished? Who is living in absolute poverty? The truth that most of us would guess is that the richest countries are often those with the least people. Compare the United States, which possesses a relatively small slice of the population pie and owns by far the largest slice of the wealth pie, with India. These disparities have the expected consequence. The poorest people in the world are women and those in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. For women, the rate of poverty is particularly worsened by the pressure on their time. In general, time is one of the few luxuries the very poor have, but study after study has shown that women in poverty, who are responsible for all family comforts as well as any earnings they can make, have less of it. The result is that while men and women may have the same rate of economic poverty, women are suffering more in terms of overall wellbeing (Buvinic 1997). It is harder for females to get credit to expand businesses, to take the time to learn a new skill, or to spend extra hours improving their craft so as to be able to earn at a higher rate.

Global Feminization of Poverty

In some ways, the phrase “global feminization of poverty” says it all: around the world, women are bearing a disproportionate percentage of the burden of poverty. This means more women live in poor conditions, receive inadequate healthcare, bear the brunt of malnutrition and inadequate drinking water, and so on. Throughout the 1990s, data indicated that while overall poverty rates were rising, especially in peripheral nations, the rates of impoverishment increased for women by nearly 20 percent more than for men (Mogadham 2005).

Why is this happening? While myriad variables affect women’s poverty, research specializing in this issue identifies three causes (Mogadham 2005):

- The expansion in the number of female-headed households

- The persistence and consequences of intra-household inequalities and biases against women

- The implementation of neoliberal economic policies around the world

While women are living longer and healthier lives today compared to ten years ago, around the world many women are denied basic rights, particularly in the workplace. In peripheral nations, they accumulate fewer assets, farm less land, make less money, and face restricted civil rights and liberties. Women can stimulate the economic growth of peripheral nations, but they are often undereducated and lack access to the credit needed to start small businesses.