Since ancient times, people have been fascinated by the relationship between individuals and the societies to which they belong. Many topics studied in modern sociology were also studied by ancient philosophers in their desire to describe an ideal society, including theories of social conflict, economics, social cohesion, and power (Hannoum 2003).

In the thirteenth century, Ma Tuan-Lin, a Chinese historian, first recognized social dynamics as an underlying component of historical development in his seminal encyclopedia, General Study of Literary Remains. The next century saw the emergence of the historian some consider to be the world’s first sociologist: Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) of Tunisia. He wrote about many topics of interest today, setting a foundation for both modern sociology and economics, including a theory of social conflict, a comparison of nomadic and sedentary life, a description of political economy, and a study connecting a tribe’s social cohesion to its capacity for power (Hannoum 2003).

But the development of Sociology as an academic discipline has its roots in revolution. The first revolution was a revolution of thought that occurred as a result of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. The Scientific Revolution showed how systematic research could uncover laws of the natural world. These methods were borrowed by individuals who applied the research principles to the social world. In the eighteenth century, Age of Enlightenment philosophers developed general principles that could be used to explain social life. Thinkers such as John Locke, Voltaire, Immanuel Kant, and Thomas Hobbes responded to what they saw as social ills by writing on topics that they hoped would lead to social reform. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) wrote about women’s conditions in society. Her works were long ignored by the male academic structure, but since the 1970s, Wollstonecraft has been widely considered the first feminist thinker of consequence. These thinkers looked to logic and reason as well as an application of scientific research to social conditions to help uncover laws about the social world.

The second revolution was a political revolution with social implications – The French Revolution. France was one of the most powerful countries in the world, along with England. The main contribution of the French Revolution to the development of Sociology as an academic discipline lies in the reaction people had to the political and social upheaval. Some people wanted society to stay the way it was while others advocated for changes to the major social institutions. These reactions are captured in the theoretical perspectives or paradigms noted below.

The third and most transformative was the Industrial revolution or the complete transformation of western society from rural and agricultural to urban and industrial. The early nineteenth century saw great changes with the Industrial Revolution, increased mobility, and new kinds of employment. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval with the rise of empires that exposed many people—for the first time—to societies and cultures other than their own. Millions of people moved into cities and many people turned away from their traditional religious beliefs. The increased urbanization and industrialization brought about new social problems that would be studied by the earliest Sociologists.

Creating a Discipline

Auguste Comte (1798–1857)

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript (Fauré et al. 1999). In 1838, the term was reinvented by Auguste Comte (1798–1857). Comte originally studied to be an engineer, but he later became a pupil of social philosopher Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). They both thought that social scientists could study society using the same scientific methods utilized in natural sciences. Comte also believed in the potential of social scientists to work toward the betterment of society. He held that once scholars identified the laws that governed society, sociologists could address problems such as poor education and poverty (Abercrombie et al. 2000).

Comte named the scientific study of social patterns positivism. He described his philosophy in a series of books called The Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842) and A General View of Positivism (1848). He believed that using scientific methods to reveal the laws by which societies and individuals interact would usher in a new “positivist” age of history.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876)—the First Woman Sociologist

Harriet Martineau was a writer who addressed a wide range of social science issues. She was an early observer of social practices, including economics, social class, religion, suicide, government, and women’s rights. Her writing career began in 1831 with a series of stories titled Illustrations of Political Economy, in which she tried to educate ordinary people about the principles of economics (Johnson 2003).

Martineau was the first to translate Comte’s writing from French to English and thereby introduced sociology to English-speaking scholars (Hill 1991). She is also credited with the first systematic methodological international comparisons of social institutions in two of her most famous sociological works: Society in America (1837) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838). Martineau found the workings of capitalism at odds with the professed moral principles of people in the United States; she pointed out the faults with the free enterprise system in which workers were exploited and impoverished while business owners became wealthy. She further noted that the belief in all being created equal was inconsistent with the lack of women’s rights. Much like Mary Wollstonecraft, Martineau was often discounted in her own time by the male domination of academic sociology.

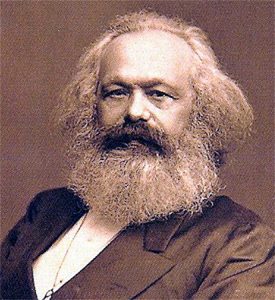

Karl Marx (1818–1883)

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher and economist. In 1848, he and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) coauthored the Communist Manifesto. This book is one of the most influential political manuscripts in history. It also presents Marx’s theory of society, which differed from what Comte proposed.

Marx rejected Comte’s positivism. He believed that societies grew and changed as a result of the struggles of different social classes over the means of production. At the time when he was developing his theories, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism led to great disparities in wealth between the owners of the factories and workers. Capitalism, an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of goods and the means to produce them, grew in many nations.

Marx predicted that the inequalities of capitalism would become so extreme that workers would eventually revolt. This would lead to the collapse of capitalism, which would be replaced by communism. Communism is an economic system under which there is no private or corporate ownership: everything is owned communally and distributed as needed. Marx believed that communism was a more equitable system than capitalism.

While his economic predictions may not have come true in the time frame he predicted, Marx’s idea that social conflict leads to change in society is still one of the major theories used in modern sociology.

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903)

In 1873, the English philosopher Herbert Spencer published The Study of Sociology, the first book with the term “sociology” in the title. Spencer rejected much of Comte’s philosophy as well as Marx’s theory of class struggle and his support of communism. Instead, he favored a form of government that allowed market forces to control capitalism. His work influenced many early sociologists, including Émile Durkheim (1858–1917).

Georg Simmel (1858–1918)

Georg Simmel was a German art critic who wrote widely on social and political issues as well. Simmel took an antipositivism stance and addressed topics such as social conflict, the function of money, individual identity in city life, and the European fear of outsiders (Stapley 2010). Much of his work focused on the micro-level theories, and it analyzed the dynamics of two-person and three-person groups. His work also emphasized individual culture as the creative capacities of individuals. Simmel’s contributions to sociology are not often included in academic histories of the discipline, perhaps overshadowed by his contemporaries Durkheim, Mead, and Weber (Ritzer and Goodman 2004).

Émile Durkheim (1858–1917)

Durkheim helped establish sociology as a formal academic discipline by establishing the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895 and by publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method in 1895. In another important work, Division of Labour in Society (1893), Durkheim laid out his theory on how societies transformed from primitive states into capitalist, industrial societies. According to Durkheim, people rise to their proper levels in society based on belief in a meritocracy.

Durkheim believed that sociologists could study objective “social facts” (Poggi 2000). He also believed that through such studies it would be possible to determine if a society was “healthy” or “pathological.” He saw healthy societies as stable, while pathological societies experienced a breakdown in social norms between individuals and society.

In 1897, Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research when he published a work titled Suicide. Durkheim examined suicide statistics in different police districts to research differences between Catholic and Protestant communities. He attributed the differences to socioreligious forces rather than to individual or psychological causes.

George Herbert Mead (1863–1931)

George Herbert Mead was a philosopher and sociologist whose work focused on the ways in which the mind and the self were developed as a result of social processes (Cronk n.d.). He argued that how an individual comes to view himself or herself is based to a very large extent on interactions with others. Mead called specific individuals that impacted a person’s life significant others, and he also conceptualized “generalized others” as the organized and generalized attitude of a social group. Mead’s work is closely associated with the symbolic interactionist approach and emphasizes the micro-level of analysis.

Max Weber (1864–1920)

Prominent sociologist Max Weber established a sociology department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919. Weber wrote on many topics related to sociology including political change in Russia and social forces that affect factory workers. He is known best for his 1904 book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The theory that Weber sets forth in this book is still controversial. Some believe that Weber argued that the beliefs of many Protestants, especially Calvinists, led to the creation of capitalism. Others interpret it as simply claiming that the ideologies of capitalism and Protestantism are complementary.

Weber believed that it was difficult, if not impossible, to use standard scientific methods to accurately predict the behavior of groups as people hoped to do. He argued that the influence of culture on human behavior had to be taken into account. This even applied to the researchers themselves, who, they believed, should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and Dilthey introduced the concept of verstehen, a German word that means to understand in a deep way. In seeking verstehen, outside observers of a social world—an entire culture or a small setting—attempt to understand it from an insider’s point of view.

In his book The Nature of Social Action (1922), Weber described sociology as striving to “interpret the meaning of social action and thereby give a causal explanation of the way in which action proceeds and the effects it produces.” He and other like-minded sociologists proposed a philosophy of antipositivism whereby social researchers would strive for subjectivity as they worked to represent social processes, cultural norms, and societal values. This approach led to some research methods whose aim was not to generalize or predict (traditional in science), but to systematically gain an in-depth understanding of social worlds.

The different approaches to research based on positivism or antipositivism are often considered the foundation for the differences found today between quantitative sociology and qualitative sociology. Quantitative sociology uses statistical methods such as surveys with large numbers of participants. Researchers analyze data using statistical techniques to see if they can uncover patterns of human behavior. Qualitative sociology seeks to understand human behavior by learning about it through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and analysis of content sources (like books, magazines, journals, and popular media).

William Edward Burghardt “W. E. B.” Du Bois (1868–1963)

W.E.B. Du Bois is a critical figure in the development of sociology. He made lasting and profound contributions to the social sciences by pioneering several sociological methodologies. For many years though, these efforts were largely ignored and omitted from history.

His now well-known studies introduced and implemented many of the principles that became the foundation for modern sociology, some 20 years before the University of Chicago developed what is considered the first department of sociology in the United States.

Du Bois was an impressive scholar, skilled civil rights activist, prolific social scientist, and the first African American to graduate from Harvard University with a doctorate.

1.3 Theoretical Perspectives

- Explain what sociological theories are and how they are used

- Understand the similarities and differences between structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism

Sociologists study social events, interactions, and patterns, and they develop a theory in an attempt to explain why things work as they do. In sociology, a theory is a way to explain different aspects of social interactions and to create a testable proposition, called a hypothesis, about society (Allan 2006).

For example, although suicide is generally considered an individual phenomenon, Émile Durkheim was interested in studying the social factors that affect it. He studied social ties within a group, or social solidarity, and hypothesized that differences in suicide rates might be explained by religion-based differences. Durkheim gathered a large amount of data about Europeans who had ended their lives, and he did indeed find differences based on religion. Protestants were more likely to commit suicide than Catholics in Durkheim’s society, and his work supports the utility of theory in sociological research.

Theories vary in scope depending on the scale of the issues that they are meant to explain. Macro-level theories relate to large-scale issues and large groups of people, while micro-level theories look at very specific relationships between individuals or small groups. Grand theories attempt to explain large-scale relationships and answer fundamental questions such as why societies form and why they change. Sociological theory is constantly evolving and should never be considered complete. Classic sociological theories are still considered important and current, but new sociological theories build upon the work of their predecessors and add to them (Calhoun 2002).

In sociology, a few theories provide broad perspectives that help explain many different aspects of social life, and these are called paradigms. Paradigms are philosophical and theoretical frameworks used within a discipline to formulate theories, generalizations, and the experiments performed in support of them. Three paradigms have come to dominate sociological thinking because they provide useful explanations: structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

| Sociological Paradigm |

Level of Analysis |

Focus |

| Structural Functionalism |

Macro or mid |

The way each part of society functions together to contribute to the whole |

| Conflict Theory |

Macro |

The way inequalities contribute to social differences and perpetuate differences in power |

| Symbolic Interactionism |

Micro |

One-to-one interactions and communications |

Table 1.1 Sociological Theories or Perspectives. Different sociological perspectives enable sociologists to view social issues through a variety of useful lenses.

Functionalism

Functionalism, also called structural-functional theory, sees society as a structure with interrelated parts designed to meet the biological and social needs of the individuals in that society. Functionalism grew out of the writings of English philosopher and biologist Hebert Spencer (1820–1903), who saw similarities between society and the human body; he argued that just as the various organs of the body work together to keep the body functioning, the various parts of society work together to keep society functioning (Spencer 1898). The parts of society that Spencer referred to were the social institutions, or patterns of beliefs and behaviors focused on meeting social needs, such as government, education, family, healthcare, religion, and the economy.

Émile Durkheim, another early sociologist, applied Spencer’s theory to explain how societies change and survive over time. Durkheim believed that society is a complex system of interrelated and interdependent parts that work together to maintain stability (Durkheim 1893) and that society is held together by shared values, languages, and symbols. He believed that to study society, a sociologist must look beyond individuals to social facts such as laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashion, and rituals, which all serve to govern social life. Alfred Radcliffe-Brown (1881–1955) defined the function of any recurrent activity as the part it plays in social life as a whole, and therefore the contribution it makes to social stability and continuity (Radcliffe-Brown 1952). In a healthy society, all parts work together to maintain stability, a state called dynamic equilibrium by later sociologists such as Parsons (1961).

Durkheim believed that individuals may make up society, but in order to study society, sociologists have to look beyond individuals to social facts. Social facts are laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and all of the cultural rules that govern social life (Durkheim 1895). Each of these social facts serves one or more functions within a society. For example, one function of a society’s laws may be to protect society from violence, while another is to punish criminal behavior, while another is to preserve public health.

Another noted structural functionalist, Robert Merton (1910–2003), pointed out that social processes often have many functions. Manifest functions are the consequences of a social process that are sought or anticipated, while latent functions are the unsought consequences of a social process. A manifest function of college education, for example, includes gaining knowledge, preparing for a career, and finding a good job that utilizes that education. Latent functions of your college years include meeting new people, participating in extracurricular activities, or even finding a spouse or partner. Another latent function of education is creating a hierarchy of employment based on the level of education attained. Latent functions can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful. Social processes that have undesirable consequences for the operation of society are called dysfunctions. In education, examples of dysfunction include getting bad grades, truancy, dropping out, not graduating, and not finding suitable employment.

Criticism

One criticism of the structural-functional theory is that it can’t adequately explain social change. Also problematic is the somewhat circular nature of this theory; repetitive behavior patterns are assumed to have a function, yet we profess to know that they have a function only because they are repeated. Furthermore, dysfunctions may continue, even though they don’t serve a function, which seemingly contradicts the basic premise of the theory. Many sociologists now believe that functionalism is no longer useful as a macro-level theory, but that it does serve a useful purpose in some mid-level analyses.

A Global Culture?

Sociologists around the world look closely for signs of what would be an unprecedented event: the emergence of a global culture. In the past, empires such as those that existed in China, Europe, Africa, and Central and South America linked people from many different countries, but those people rarely became part of a common culture. They lived too far from each other, spoke different languages, practiced different religions, and traded few goods. Today, increases in communication, travel, and trade have made the world a much smaller place. More and more people are able to communicate with each other instantly—wherever they are located—by telephone, video, and text. They share movies, television shows, music, games, and information over the Internet. Students can study with teachers and pupils from the other side of the globe. Governments find it harder to hide conditions inside their countries from the rest of the world.

Sociologists research many different aspects of this potential global culture. Some explore the dynamics involved in the social interactions of global online communities, such as when members feel a closer kinship to other group members than to people residing in their own countries. Other sociologists study the impact this growing international culture has on smaller, less-powerful local cultures. Yet other researchers explore how international markets and the outsourcing of labor impact social inequalities. Sociology can play a key role in people’s ability to understand the nature of this emerging global culture and how to respond to it.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory looks at society as a competition for limited resources. This perspective is a macro-level approach most identified with the writings of German philosopher and sociologist Karl Marx (1818–1883), who saw society as being made up of individuals in different social classes who must compete for social, material, and political resources such as food and housing, employment, education, and leisure time. Social institutions like government, education, and religion reflect this competition in their inherent inequalities and help maintain the unequal social structure. Some individuals and organizations are able to obtain and keep more resources than others, and these “winners” use their power and influence to maintain social institutions. Several theorists suggested variations on this basic theme.

Polish-Austrian sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz (1838–1909) expanded on Marx’s ideas by arguing that war and conquest are the basis of civilizations. He believed that cultural and ethnic conflicts led to states being identified and defined by a dominant group that had power over other groups (Irving 2007).

German sociologist Max Weber agreed with Marx but also believed that, in addition to economic inequalities, inequalities of political power and social structure cause conflict. Weber noted that different groups were affected differently based on education, race, and gender and that people’s reactions to inequality were moderated by class differences and rates of social mobility, as well as by perceptions about the legitimacy of those in power.

German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918) believed that conflict can help integrate and stabilize a society. He said that the intensity of the conflict varies depending on the emotional involvement of the parties, the degree of solidarity within the opposing groups, and the clarity and limited nature of the goals. Simmel also showed that groups work to create internal solidarity, centralize power, and reduce dissent. Resolving conflicts can reduce tension and hostility and can pave the way for future agreements.

In the 1930s and 1940s, German philosophers, known as the Frankfurt School, developed critical theory as an elaboration on Marxist principles. Critical theory is an expansion of conflict theory and is broader than just sociology, including other social sciences and philosophy. Critical theory attempts to address structural issues causing inequality; it must explain what’s wrong in the current social reality, identify the people who can make changes, and provide practical goals for social transformation (Horkeimer 1982).

More recently, inequality based on gender or race has been explained in a similar manner, and institutionalized power structures have been identified that help to maintain inequality between groups. Janet Saltzman Chafetz (1941–2006) presented a model of feminist theory that attempts to explain the forces that maintain gender inequality as well as a theory of how such a system can be changed (Turner 2003). Similarly, critical race theory grew out of a critical analysis of race and racism from a legal point of view. Critical race theory looks at structural inequality based on white privilege and associated wealth, power, and prestige.

Criticism

Just as structural functionalism was criticized for focusing too much on the stability of societies, conflict theory has been criticized because it tends to focus on conflict to the exclusion of recognizing stability. Many social structures are extremely stable or have gradually progressed over time rather than changing abruptly as conflict theory would suggest.

SOCIOLOGY IN THE REAL WORLD

Farming and Locavores: How Sociological Perspectives Might View Food Consumption

The consumption of food is a commonplace, daily occurrence, yet it can also be associated with important moments in our lives. Eating can be an individual or a group action, and eating habits and customs are influenced by our cultures. In the context of society, our nation’s food system is at the core of numerous social movements, political issues, and economic debates. Any of these factors might become a topic of sociological study.

A structural-functional approach to the topic of food consumption might be interested in the role of the agriculture industry within the nation’s economy and how this has changed from the early days of manual-labor farming to modern mechanized production. Another examination might study the different functions that occur in food production: from farming and harvesting to flashy packaging and mass consumerism.

A conflict theorist might be interested in the power differentials present in the regulation of food, by exploring where people’s right to information intersects with corporations’ drive for profit and how the government mediates those interests. Or a conflict theorist might be interested in the power and powerlessness experienced by local farmers versus large farming conglomerates, which the documentary Food Inc. depicts as resulting from Monsanto’s patenting of seed technology. Another topic of study might be how nutrition varies between different social classes.

A sociologist viewing food consumption through a symbolic interactionist lens would be more interested in micro-level topics, such as the symbolic use of food in religious rituals, or the role it plays in the social interaction of a family dinner. This perspective might also study the interactions among group members who identify themselves based on their sharing a particular diet, such as vegetarians (people who don’t eat meat) or locavores (people who strive to eat locally produced food).

Symbolic Interactionist Theory

Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level theory that focuses on the relationships among individuals within a society. Communication—the exchange of meaning through language and symbols—is believed to be the way in which people make sense of their social worlds. Theorists Herman and Reynolds (1994) note that this perspective sees people as being active in shaping the social world rather than simply being acted upon.

George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) is considered a founder of symbolic interactionism though he never published his work on it (LaRossa and Reitzes 1993). Mead’s student, Herbert Blumer, coined the term “symbolic interactionism” and outlined these basic premises: humans interact with things based on meanings ascribed to those things; the ascribed meaning of things comes from our interactions with others and society; the meanings of things are interpreted by a person when dealing with things in specific circumstances (Blumer 1969). If you love books, for example, a symbolic interactionist might propose that you learned that books are good or important in the interactions you had with family, friends, school, or church; maybe your family had a special reading time each week, getting your library card was treated as a special event, or bedtime stories were associated with warmth and comfort.

Social scientists who apply symbolic-interactionist thinking look for patterns of interaction between individuals. Their studies often involve the observation of one-on-one interactions. For example, while a conflict theorist studying a political protest might focus on class differences, a symbolic interactionist would be more interested in how individuals in the protesting group interact, as well as the signs and symbols protesters use to communicate their message. The focus on the importance of symbols in building a society led sociologists like Erving Goffman (1922–1982) to develop a technique called dramaturgical analysis. Goffman used theater as an analogy for social interaction and recognized that people’s interactions showed patterns of cultural “scripts.” Because it can be unclear what part a person may play in a given situation, he or she has to improvise his or her role as the situation unfolds (Goffman 1958).

Studies that use the symbolic interactionist perspective are more likely to use qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews or participant observation, because they seek to understand the symbolic worlds in which research subjects live.

Constructivism is an extension of symbolic interaction theory which proposes that reality is what humans cognitively construct it to be. We develop social constructs based on interactions with others, and those constructs that last over time are those that have meanings that are widely agreed-upon or generally accepted by most within the society. This approach is often used to understand what’s defined as deviant within a society. There is no absolute definition of deviance, and different societies have constructed different meanings for deviance, as well as associating different behaviors with deviance. One situation that illustrates this is what you believe you’re to do if you find a wallet in the street. In the United States, turning the wallet in to local authorities would be considered the appropriate action, and to keep the wallet would be seen as deviant. In contrast, many Eastern societies would consider it much more appropriate to keep the wallet and search for the owner yourself; turning it over to someone else, even the authorities, would be considered deviant behavior.

Criticism

Research done from this perspective is often scrutinized because of the difficulty of remaining objective. Others criticize the extremely narrow focus on symbolic interaction. Proponents, of course, consider this one of its greatest strengths.

Sociological Theory Today

These three approaches are still the main foundation of modern sociological theory, but some evolution has been seen. Structural-functionalism was a dominant force after World War II and until the 1960s and 1970s. At that time, sociologists began to feel that structural-functionalism did not sufficiently explain the rapid social changes happening in the United States at that time.

Conflict theory then gained prominence, as there was a renewed emphasis on institutionalized social inequality. Critical theory, and the particular aspects of feminist theory and critical race theory, focused on creating social change through the application of sociological principles, and the field saw a renewed emphasis on helping ordinary people understand sociology principles, in the form of public sociology.

Postmodern social theory attempts to look at society through an entirely new lens by rejecting previous macro-level attempts to explain social phenomena. Generally considered as gaining acceptance in the late 1970s and early 1980s, postmodern social theory is a micro-level approach that looks at small, local groups and individual reality. Its growth in popularity coincides with the constructivist aspects of symbolic interactionism.

1.4 Why Study Sociology?

- Explain why it is worthwhile to study sociology

When Elizabeth Eckford tried to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in September 1957, she was met by an angry crowd. But she knew she had the law on her side. Three years earlier in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned twenty-one state laws that allowed blacks and whites to be taught in separate school systems as long as the school systems were “equal.” One of the major factors influencing that decision was research conducted by the husband-and-wife team of sociologists, Kenneth and Mamie Clark. Their research showed that segregation was harmful to young black schoolchildren, and the Court found that harm to be unconstitutional.

Since it was first founded, many people interested in sociology have been driven by the scholarly desire to contribute knowledge to this field, while others have seen it as a way not only to study society but also to improve it. Besides desegregation, sociology has played a crucial role in many important social reforms, such as equal opportunity for women in the workplace, improved treatment for individuals with mental disabilities or learning disabilities, increased accessibility and accommodation for people with physical handicaps, the right of native populations to preserve their land and culture, and prison system reforms.

The prominent sociologist Peter L. Berger (1929–1917), in his 1963 book Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective, describes a sociologist as “someone concerned with understanding society in a disciplined way.” He asserts that sociologists have a natural interest in the monumental moments of people’s lives, as well as a fascination with banal, everyday occurrences. Berger also describes the “aha” moment when a sociological theory becomes applicable and understood:

There is a deceptive simplicity and obviousness about some sociological investigations. One reads them, nods at the familiar scene, remarks that one has heard all this before and don’t people have better things to do than to waste their time on truisms—until one is suddenly brought up against an insight that radically questions everything one had previously assumed about this familiar scene. This is the point at which one begins to sense the excitement of sociology.

(Berger, 1963)

Sociology can be exciting because it teaches people ways to recognize how they fit into the world and how others perceive them. Looking at themselves and society from a sociological perspective helps people see where they connect to different groups based on the many different ways they classify themselves and how society classifies them in turn. It raises awareness of how those classifications—such as economic and status levels, education, ethnicity, or sexual orientation—affect perceptions.

Sociology teaches people not to accept easy explanations. It teaches them a way to organize their thinking so that they can ask better questions and formulate better answers. It makes people more aware that there are many different kinds of people in the world who do not necessarily think the way they do. It increases their willingness and ability to try to see the world from other people’s perspectives. This prepares them to live and work in an increasingly diverse and integrated world.

1.5 How to Study Sociology

- Define and describe the scientific method

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research

- Define what reliability and validity mean in a research study

Have you ever wondered if home schooling affects a person’s later success in college or how many people wait until they are in their forties to get married? Do you wonder if texting is changing teenagers’ abilities to spell correctly or to communicate clearly? How do social movements like Occupy Wall Street develop? How about the development of social phenomena like the massive public followings for TikTok and Harry Potter? The goal of research is to answer questions. Sociological research attempts to answer a vast variety of questions, such as these and more, about our social world.

We often have opinions about social situations, but these may be biased by our expectations or based on limited data. Instead, scientific research is based on empirical evidence, which is evidence that comes from direct experience, scientifically gathered data, or experimentation. Many people believe, for example, that crime rates go up when there’s a full moon, but research doesn’t support this opinion. Researchers Rotton and Kelly (1985) conducted a meta-analysis of research on the full moon’s effects on behavior. Meta-analysis is a technique in which the results of virtually all previous studies on a specific subject are evaluated together. Rotton and Kelly’s meta-analysis included thirty-seven prior studies on the effects of the full moon on crime rates, and the overall findings were that full moons are entirely unrelated to crime, suicide, psychiatric problems, and crisis center calls (cited in Arkowitz and Lilienfeld 2009). We may each know of an instance in which a crime happened during a full moon, but it was likely just a coincidence.

People commonly try to understand the happenings in their world by finding or creating an explanation for an occurrence. Social scientists may develop a hypothesis for the same reason. A hypothesis is a testable educated guess about predicted outcomes between two or more variables; it’s a possible explanation for specific happenings in the social world and allows for testing to determine whether the explanation holds true in many instances, as well as among various groups or in different places. Sociologists use empirical data and the scientific method, or an interpretative framework, to increase understanding of societies and social interactions, but research begins with the search for an answer to a question.

Then sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions; no topic is off-limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered workplace patterns that have transformed industries, family patterns that have enlightened family members, and education patterns that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

The crime during a full moon discussion put forth a few loosely stated opinions. If the human behaviors around those claims were tested systematically, a police officer, for example, could write a report and offer the findings to sociologists and the world in general. The new perspective could help people understand themselves and their neighbors and help people make better decisions about their lives. It might seem strange to use scientific practices to study social trends, but, as we shall see, it’s extremely helpful to rely on systematic approaches that research methods provide.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the sociologist forms the question, he or she proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

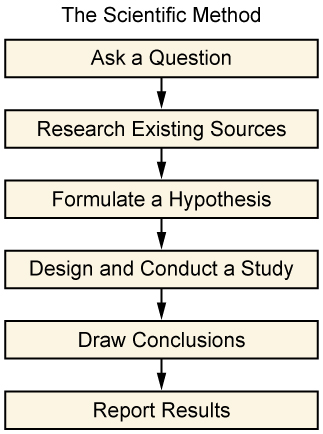

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scholarship.

But just because sociological studies use scientific methods does not make the results less human. Sociological topics are not reduced to right or wrong facts. In this field, results of studies tend to provide people with access to knowledge they did not have before—knowledge of other cultures, knowledge of rituals and beliefs, or knowledge of trends and attitudes. No matter what research approach they use, researchers want to maximize the study’s reliability, which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group. Researchers also strive for validity, which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. Returning to the crime rate during a full moon topic, the reliability of a study would reflect how well the resulting experience represents the average adult crime rate during a full moon. Validity would ensure that the study’s design accurately examined what it was designed to study, so an exploration of adult criminal behaviors during a full moon should address that issue and not veer into other age groups’ crimes, for example.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This doesn’t mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in a particular study.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963).

Typically, the scientific method starts with these steps—(1) ask a question, (2) research existing sources, (3) formulate a hypothesis—described below.

Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, describe a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geography and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. That said, happiness and hygiene are worthy topics to study. Sociologists do not rule out any topic but strive to frame these questions in better research terms.

That is why sociologists are careful to define their terms. In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?” When forming these basic research questions, sociologists develop an operational definition—that is, they define the concept in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing a variable of the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner.

The operational definition must be valid, appropriate, and meaningful. And it must be reliable, meaning that results will be close to uniform when tested on more than one person. For example, “good drivers” might be defined in many ways: those who use their turn signals, those who don’t speed, or those who courteously allow others to merge. But these driving behaviors could be interpreted differently by different researchers and could be difficult to measure. Alternatively, “a driver who has never received a traffic violation” is a specific description that will lead researchers to obtain the same information, so it is an effective operational definition.

Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library and a thorough online search will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted on the topic at hand and enables them to position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study hygiene and its value in a particular society, a researcher might sort through existing research and unearth studies about child-rearing, vanity, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and cultural attitudes toward beauty. It’s important to sift through this information and determine what is relevant. Using existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve studies’ designs.

Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an assumption about how two or more variables are related; it makes a conjectural statement about the relationship between those variables. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. In research, independent variables are the cause of the change. The dependent variable is the effect, or thing that is changed.

For example, in a basic study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by the level of education (the independent variable)?

| Hypothesis |

Independent Variable |

Dependent Variable |

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. |

Affordable Housing |

Homeless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. |

Math Tutoring |

Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighborhood. |

Police Patrol Presence |

Safer Neighborhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. |

Factory Lighting |

Productivity |

| The greater the amount of observation, the higher the public awareness. |

Observation |

Public Awareness |

Table 1.2 Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables. Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way.

At this point, a researcher’s operational definitions help measure the variables. In a study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” Another operational definition might describe “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” Those definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

As the table shows, an independent variable is the one that causes a dependent variable to change. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Or rephrased, a child’s sense of self-esteem depends, in part, on the quality and availability of hygienic resources.

Of course, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. Perhaps a sociologist believes that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will automatically increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two topics, or variables, is not enough; their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Just because a sociologist forms an educated prediction of a study’s outcome doesn’t mean data contradicting the hypothesis aren’t welcome. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While it has become at least a cultural assumption that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results will vary.

Once the preliminary work is done, it’s time for the next research steps: designing and conducting a study and drawing conclusions. These research methods are discussed below.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework. While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective, seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects. This type of researcher also learns as he or she proceeds and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Summary

1.1 What Is Sociology?

Sociology is the systematic study of social institutions, social relationships, and society. In order to carry out their studies, sociologists identify cultural patterns and social forces and determine how they affect individuals and groups. They also develop ways to apply their findings to the real world.

1.2 The History of Sociology

Sociology was developed as a way to study and try to understand the changes to society brought on by the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of the earliest sociologists thought that societies and individuals’ roles in society could be studied using the same scientific methodologies that were used in the natural sciences, while others believed that it was impossible to predict human behavior scientifically, and still others debated the value of such predictions. Those perspectives continue to be represented within sociology today.

1.3 Theoretical Perspectives

Sociologists develop theories to explain social events, interactions, and patterns. A theory is a proposed explanation of those social interactions. Theories have different scales. Macro-level theories, such as structural functionalism and conflict theory, attempt to explain how societies operate as a whole. Micro-level theories, such as symbolic interactionism, focus on interactions between individuals.

1.4 Why Study Sociology?

Studying sociology is beneficial both for the individual and for society. By studying sociology people learn how to think critically about social issues and problems that confront our society. The study of sociology enriches students’ lives and prepares them for careers in an increasingly diverse world. Society benefits because people with sociological training are better prepared to make informed decisions about social issues and take effective action to deal with them.

1.5 How to Study Sociology

Using the scientific method, a researcher conducts a study in five phases: asking a question, researching existing sources, formulating a hypothesis, conducting a study, and drawing conclusions. The scientific method is useful in that it provides a clear method of organizing a study. Some sociologists conduct research through an interpretive framework rather than employing the scientific method.

Scientific sociological studies often observe relationships between variables. Researchers study how one variable changes another. Prior to conducting a study, researchers are careful to apply operational definitions to their terms and to establish dependent and independent variables.

Key Terms

- antipositivism

- the view that social researchers should strive for subjectivity as they work to represent social processes, cultural norms, and societal values

- conflict theory

- a theory that looks at society as a competition for limited resources

- constructivism

- an extension of symbolic interaction theory which proposes that reality is what humans cognitively construct it to be

- correlation

- when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable but does not necessarily indicate causation

- culture

- a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs

- dependent variable

- a variable changed by other variables

- dramaturgical analysis

- a technique sociologists use in which they view society through the metaphor of theatrical performance

- dynamic equilibrium

- a stable state in which all parts of a healthy society work together properly

- dysfunctions

- social patterns that have undesirable consequences for the operation of society

- figuration

- the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of an individual and the society that shapes that behavior

- function

- the part a recurrent activity plays in the social life as a whole and the contribution it makes to structural continuity

- functionalism

- a theoretical approach that sees society as a structure with interrelated parts designed to meet the biological and social needs of individuals that make up that society

- generalized others

- the organized and generalized attitude of a social group

- grand theories

- an attempt to explain large-scale relationships and answer fundamental questions such as why societies form and why they change

- hypothesis

- a testable proposition

- independent variables

- variables that cause changes in dependent variables

- latent functions

- the unrecognized or unintended consequences of a social process

- macro-level

- a wide-scale view of the role of social structures within a society

- manifest functions

- sought consequences of a social process

- micro-level theories

- the study of specific relationships between individuals or small groups

- paradigms

- philosophical and theoretical frameworks used within a discipline to formulate theories, generalizations, and the experiments performed in support of them

- positivism

- the scientific study of social patterns

- qualitative sociology

- in-depth interviews, focus groups, and/or analysis of content sources as the source of its data

- quantitative sociology

- statistical methods such as surveys with large numbers of participants

- reification

- an error of treating an abstract concept as though it has a real, material existence

- scientific method

- an established scholarly research method that involves asking a question, researching existing sources, forming a hypothesis, designing and conducting a study, and drawing conclusions

- significant others

- specific individuals that impact a person’s life

- social facts

- the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and all of the cultural rules that govern social life

- social institutions

- patterns of beliefs and behaviors focused on meeting social needs

- social solidarity

- the social ties that bind a group of people together such as kinship, shared location, and religion

- society

- a group of people who live in a defined geographical area, interact with one another, and share a common culture

- sociological imagination

- the ability to understand how your own past relates to that of other people, as well as to history in general and societal structures in particular

- sociology

- the systematic study of society and social interaction

- symbolic interactionism

- a theoretical perspective through which scholars examine the relationship of individuals within their society by studying their communication (language and symbols)

- theory

- a proposed explanation about social interactions or society

- validity

- the degree to which a sociological measure accurately reflects the topic of study

- verstehen

- a German word that means to understand in a deep way

References

1.1 What Is Sociology?

Elias, Norbert. 1978. What Is Sociology? New York: Columbia University Press.

Ludden, Jennifer. 2012. “Single Dads By Choice: More Men Going It Alone.” npr. Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://www.npr.org/2012/06/19/154860588/single-dads-by-choice-more-men-going-it-alone).

Mills, C. Wright. 2000 [1959]. The Sociological Imagination. 40th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sahn, Richard. 2013. “The Dangers of Reification.” The Contrary Perspective. Retrieved October 14, 2014 (http://contraryperspective.com/2013/06/06/the-dangers-of-reification/).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2013. “America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2012.” Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-570.pdf).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2021. “Percentage and Number of Children Living with Two Parents Has Dropped Since 1968.” (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/number-of-children-living-only-with-their-mothers-has-doubled-in-past-50-years.html)

1.2 The History of Sociology

Abercrombie, Nicholas, Stephen Hill, and Bryan S. Turner. 2000. The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology. London: Penguin.

Buroway, Michael. 2005. “2004 Presidential Address: For Public Sociology.” American Sociological Review 70 (February): 4–28. Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://burawoy.berkeley.edu/Public%20Sociology,%20Live/Burawoy.pdf).

Cable Network News (CNN). 2014. “Should the minimum wage be raised?” CNN Money. Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://money.cnn.com/infographic/pf/low-wage-worker/).

Cronk, George. n.d. “George Herbert Mead.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: A Peer-Reviewed Academic Resource. Retrieved October 14, 2014 (http://www.iep.utm.edu/mead/).

Durkheim, Émile. 1964 [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method, edited by J. Mueller, E. George and E. Caitlin. 8th ed. Translated by S. Solovay. New York: Free Press.

Fauré, Christine, Jacques Guilhaumou, Jacques Vallier, and Françoise Weil. 2007 [1999]. Des Manuscrits de Sieyès, 1773–1799, Volumes I and II. Paris: Champion.

Hannoum, Abdelmajid. 2003. Translation and the Colonial Imaginary: Ibn Khaldun Orientalist. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (http://www.jstor.org/pss/3590803).

Hill, Michael. 1991. “Harriet Martineau.” Women in Sociology: A Bio-Bibliographic Sourcebook, edited by Mary Jo Deegan. New York: Greenwood Press.

Johnson, Bethany. 2003. “Harriet Martineau: Theories and Contributions to Sociology.” Education Portal. Retrieved October 14, 2014 (http://education-portal.com/academy/lesson/harriet-martineau-theories-and-contributions-to-sociology.html#lesson).

Poggi, Gianfranco. 2000. Durkheim. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Ritzer, George, and Goodman, Douglas. 2004. Sociological Theory, 6th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Education.

Stapley, Pierre. 2010. “Georg Simmel.” Cardiff University School of Social Sciences. Retrieved October 21, 2014 (http://www.cf.ac.uk/socsi/undergraduate/introsoc/simmel.html).

U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. 2010. Women and the Economy, 2010: 25 Years of Progress But Challenges Remain. August. Washington, DC: Congressional Printing Office. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (http://jec.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File_id=8be22cb0-8ed0-4a1a-841b-aa91dc55fa81).

1.3 Theoretical Perspectives

Allan, Kenneth. 2006. Contemporary Social and Sociological Theory: Visualizing Social Worlds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Broce, Gerald. 1973. History of Anthropology. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company.

Calhoun, Craig J. 2002. Classical Sociological Theory. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Durkheim, Émile. 1984 [1893]. The Division of Labor in Society. New York: Free Press.

Durkheim, Émile. 1964 [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method, edited by J. Mueller, E. George and E. Caitlin. 8th ed. Translated by S. Solovay. New York: Free Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1958. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, Social Sciences Research Centre.

Goldschmidt, Walter. 1996. “Functionalism” in Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 2, edited by D. Levinson and M. Ember. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Henry, Stuart. 2007. “Deviance, Constructionist Perspectives.” Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Retrieved October 14, 2014 (http://www.sociologyencyclopedia.com/public/tocnode?id=g9781405124331_yr2011_chunk_g978140512433110_ss1-41).

Herman, Nancy J., and Larry T. Reynolds. 1994. Symbolic Interaction: An Introduction to Social Psychology. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

Horkeimer, M. 1982. Critical Theory. New York: Seabury Press.

Irving, John Scott. 2007. Fifty Key Sociologists: The Formative Theorists. New York: Routledge.

LaRossa, R., and D.C. Reitzes. 1993. “Symbolic Interactionism and Family Studies.” Pp. 135–163 in Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach, edited by P. G. Boss, W. J. Doherty, R. LaRossa, W. R. Schumm, and S. K. Steinmetz. New York: Springer.

Maryanski, Alexandra, and Jonathan Turner. 1992. The Social Cage: Human Nature and the Evolution of Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 1998 [1848]. The Communist Manifesto. New York: Penguin.

Parsons, T. 1961. Theories of Society: Foundations of Modern Sociological Theory. New York: Free Press.

Pew Research Center. 2012. “Mobile Technology Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Internet Project, April 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/).

Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. 1952. Structure and Function in Primitive Society: Essays and Addresses. London: Cohen and West.

Spencer, Herbert. 1898. The Principles of Biology. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Turner, J. 2003. The Structure of Sociological Theory. 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Thompson/Wadsworth.

UCLA School of Public Affairs. n.d. “What is Critical Race Theory?” UCLA School of Public Affairs: Critical Race Studies. Retrieved October 20, 2014 (http://spacrs.wordpress.com/what-is-critical-race-theory/).

1.4 Why Study Sociology?

Berger, Peter L. 1963. Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Department of Sociology, University of Alabama. N.d. Is Sociology Right for You? Huntsville: University of Alabama. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (https://www.uah.edu/ahs/departments/sociology/about).

Arkowitz, Hal, and Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2009. “Lunacy and the Full Moon: Does a full moon really trigger strange behavior?” Scientific American. Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lunacy-and-the-full-moon/).

Rotton, James, and Ivan W. Kelly. 1985. “Much Ado about the Full Moon: A Meta-analysis of Lunar-Lunacy Research.” Psychological Bulletin 97 (no. 2): 286–306.

1.5 How to Study Sociology

Arkowitz, Hal, and Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2009. “Lunacy and the Full Moon: Does a full moon really trigger strange behavior?” Scientific American. Retrieved October 20, 2014 (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lunacy-and-the-full-moon).

Berger, Peter L. 1963. Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Merton, Robert. 1968 [1949]. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

“Scientific Method Lab,” the University of Utah, http://aspire.cosmic-ray.org/labs/scientific_method/sci_method_main.html.