7 Race and Ethnicity

Trayvon Martin was a seventeen-year-old black teenager. On the evening of February 26, 2012, he was visiting with his father and his father’s fiancée in the Sanford, Florida, multi-ethnic gated community where his father’s fiancée lived. Trayvon went on foot to buy a snack from a nearby convenience store. As he was returning, George Zimmerman, a white Hispanic male, and the community’s neighborhood watch program coordinator noticed him. In light of a recent rash of break-ins, Zimmerman called the police to report a person acting suspiciously, which he had done on many other occasions. The 911 operator told Zimmerman not to follow the teen, but soon after Zimmerman and Martin had a physical confrontation. According to Zimmerman, Martin attacked him, and in the ensuing scuffle, Martin was shot and killed (CNN Library 2014).

A public outcry followed Martin’s death. There were allegations of racial profiling—the use by law enforcement of race alone to determine whether to stop and detain someone—a national discussion about “Stand Your Ground Laws,” and a failed lawsuit in which Zimmerman accused NBC of airing an edited version of the 911 call that made him appear racist. Zimmerman was not arrested until April 11, when he was charged with second-degree murder by special prosecutor Angela Corey. In the ensuing trial, he was found not guilty (CNN Library 2014).

The shooting, the public response, and the trial that followed offer a snapshot of the sociology of race. Do you think race played a role in Martin’s death or in the public reaction to it? Do you think race had any influence on the initial decision not to arrest Zimmerman, or on his later acquittal? Does society fear black men, leading to racial profiling at an institutional level? What about the role of the media? Was there a deliberate attempt to manipulate public opinion? If you were a member of the jury, would you have convicted George Zimmerman?

Since Trayvon’s death, many similar cases have showcased the wrongful deaths of Black Americans. It is reported that Police officers killed at least 200 Black people in 2021 (Newsweek, 2022). One death that displayed the most outcry compared to Trayvon Martin was George Floyd, who was killed on May 25, 2020, while in police custody. Floyd’s unfortunate death helped spark a nationwide debate about racism, police brutality, and systemic racism (Newsweek, 2022). As a result, many people participated globally in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement. This awareness targets Blacks who were mistreated and other ethnicities, such as Asian Americans, who experienced an increase of 339 percent in hate crimes in 2021; nonetheless, Black Americans remain the most targeted group to experience crimes associated with hatred (NBC News, 2022).

7.1 Racial, Ethnic, and Minority Groups

Learning Objectives

- Understand the difference between race and ethnicity

- Define a majority group (dominant group)

- Define a minority group (subordinate group)

While many students first entering a sociology classroom are accustomed to conflating the terms “race,” “ethnicity,” and “minority group,” these three terms have distinct meanings for sociologists. The idea of race refers to superficial physical differences that a particular society considers significant, while ethnicity describes shared culture. And the term “minority groups” describe groups that are subordinate, or that lack power in society regardless of skin color or country of origin. For example, in modern U.S. history, the elderly might be considered a minority group due to a diminished status that results from popular prejudice and discrimination against them. Ten percent of nursing home staff admitted to physically abusing an elderly person in the past year, and 40 percent admitted to committing psychological abuse (World Health Organization 2011). In this chapter, we focus on racial and ethnic minorities.

What Is Race?

Historically, the concept of race has changed across cultures and eras and has eventually become less connected with ancestral and familial ties, and more concerned with superficial physical characteristics. In the past, theorists have posited categories of race based on various geographic regions, ethnicities, skin colors, and more. Their labels for racial groups have connoted regions (Mongolia and the Caucasus Mountains, for instance) or skin tones (black, white, yellow, and red, for example).

Social science organizations including the American Association of Anthropologists, the American Sociological Association, and the American Psychological Association have all taken an official position rejecting the biological explanations of race. Over time, the typology of race that developed during early racial science has fallen into disuse, and the social construction of race is a more sociological way of understanding racial categories. Research in this school of thought suggests that race is not biologically identifiable and that previous racial categories were arbitrarily assigned, based on pseudoscience, and used to justify racist practices (Omi and Winant 1994; Graves 2003). When considering skin color, for example, the social construction of race perspective recognizes that the relative darkness or fairness of skin is an evolutionary adaptation to the available sunlight in different regions of the world. Contemporary conceptions of race, therefore, which tend to be based on socioeconomic assumptions, illuminate how far removed modern understanding of race is from biological qualities.

The social construction of race is also reflected in the way names for racial categories change with changing times. It’s worth noting that race, in this sense, is also a system of labeling that provides a source of identity; specific labels fall in and out of favor during different social eras. For example, the category “negroid,” popular in the nineteenth century, evolved into the term “negro” by the 1960s, and then this term fell from use and was replaced with “African American.” This latter term was intended to celebrate the multiple identities that a black person might hold, but the word choice is a poor one: it lumps together a large variety of ethnic groups under an umbrella term while excluding others who could accurately be described by the label but who do not meet the spirit of the term. For example, actress Charlize Theron is a blonde-haired, blue-eyed “African American.” She was born in South Africa and later became a U.S. citizen. Is her identity that of an “African American” as most of us understand the term?

What Is Ethnicity?

Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture—the practices, values, and beliefs of a group. This culture might include shared language, religion, and traditions, among other commonalities. Like race, the term ethnicity is difficult to describe, and its meaning has changed over time. And as with race, individuals may be identified or self-identify with ethnicities in complex, even contradictory, ways. For example, ethnic groups such as Irish, Italian American, Russian, Jewish, and Serbian might all be groups whose members are predominantly included in the “white” racial category. Conversely, the ethnic group British includes citizens from a multiplicity of racial backgrounds: black, white, Asian, and more, plus a variety of race combinations. These examples illustrate the complexity and overlap of these identifying terms. Ethnicity, like race, continues to be an identification method that individuals and institutions use today—whether through the census, affirmative action initiatives, nondiscrimination laws, or simply in personal day-to-day relations.

What Are Minority Groups?

Sociologist Louis Wirth (1945) defined a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.” The term minority connotes discrimination, and in its sociological use, the term subordinate group can be used interchangeably with the term minority, while the term dominant group is often substituted for the group that’s in the majority. These definitions correlate to the concept that the dominant group is that which holds the most power in a given society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group.

Note that being a numerical minority is not a characteristic of being a minority group; sometimes larger groups can be considered minority groups due to their lack of power. It is the lack of power that is the predominant characteristic of a minority, or subordinate group. For example, consider apartheid in South Africa, in which a numerical majority (the black inhabitants of the country) were exploited and oppressed by the white minority.

According to Charles Wagley and Marvin Harris (1958), a minority group is distinguished by five characteristics: (1) unequal treatment and less power over their lives, (2) distinguishing physical or cultural traits like skin color or language, (3) involuntary membership in the group, (4) awareness of subordination, and (5) high rate of in-group marriage. Additional examples of minority groups might include the LGBT community, religious practitioners whose faith is not widely practiced where they live, and people with disabilities.

Scapegoat theory, developed initially from Dollard’s (1939) Frustration-Aggression theory, suggests that the dominant group will displace its unfocused aggression onto a subordinate group. History has shown us many examples of the scapegoating of a subordinate group. An example from the last century is the way Adolf Hitler was able to blame the Jewish population for Germany’s social and economic problems. In the United States, recent immigrants have frequently been the scapegoat for the nation’s—or an individual’s—woes. Many states have enacted laws to disenfranchise immigrants; these laws are popular because they let the dominant group scapegoat a subordinate group.

7.2 Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Learning Objectives

- Explain the difference between stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and racism

- Identify different types of discrimination

- View racial tension through a sociological lens

The terms stereotype, prejudice, discrimination, and racism are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. Let us explore the differences between these concepts. Stereotypes are oversimplified generalizations about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive (usually about one’s own group, such as when women suggest they are less likely to complain about physical pain) but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is stupid or lazy). In either case, the stereotype is a generalization that doesn’t take individual differences into account.

Where do stereotypes come from? In fact, new stereotypes are rarely created; rather, they are recycled from subordinate groups that have assimilated into society and are reused to describe newly subordinate groups. For example, many stereotypes that are currently used to characterize black people were used earlier in American history to characterize Irish and Eastern European immigrants. For example, the word “ghetto” is associated with run-down and high-crime living areas for Black people. However, this word was used in the 16th century for Jews living in Venice. These individuals were cast into the city’s northern parts known as “The New Ghetto” (Time, 2019).

Prejudice and Racism

Prejudice refers to the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. Prejudice is not based on experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience. A 1970 documentary called Eye of the Storm illustrates the way in which prejudice develops, by showing how defining one category of people as superior (children with blue eyes) results in prejudice against people who are not part of the favored category.

While prejudice is not necessarily specific to race, racism is a stronger type of prejudice used to justify the belief that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is also a set of practices used by a racial majority to disadvantage a racial minority. The Ku Klux Klan is an example of a racist organization; its members’ belief in white supremacy has encouraged over a century of hate crime and hate speech.

Institutional racism refers to the way in which racism is embedded in the fabric of society. For example, the disproportionate number of black men arrested, charged, and convicted of crimes may reflect racial profiling, a form of institutional racism. Other forms of institutional racism may include residential segregation, unfair lending practices and other barriers to homeownership and accumulating wealth, schools’ dependence on local property taxes, environmental injustice, biased policing of men and boys of color, and voter suppression policies (Braveman, Arkin, Proctor, Kauh, & Holm, 2022).

Colorism is another kind of prejudice, in which someone believes one type of skin tone is superior or inferior to another within a racial group. Studies suggest that darker-skinned African Americans experience more discrimination than lighter-skinned African Americans (Herring, Keith, and Horton 2004; Klonoff and Landrine 2000). For example, if a white employer believes a black employee with a darker skin tone is less capable than a black employee with a lighter skin tone, that is colorism. At least one study suggested that colorism affected racial socialization, with darker-skinned black male adolescents receiving more warnings than lighter-skinned black male adolescents about the danger of interacting with members of other racial groups (Landor et al. 2013). Although the topic of colorism is popular amongst Blacks, other cultures and ethnic groups experience these occurrences. CNN Health (2018) reports, “In many societies, especially in Asia, skin color was long seen as a sign of social class.… With Western colonial incursions during the 18th and 19th century, the light skin of European colonizers became a marker of higher status, while the darker skin of Asians/Filipinos became a marker of colonial subjugation.”

Discrimination

While prejudice refers to biased thinking, discrimination consists of actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on age, religion, health, and other indicators; race-based laws against discrimination strive to address this set of social problems.

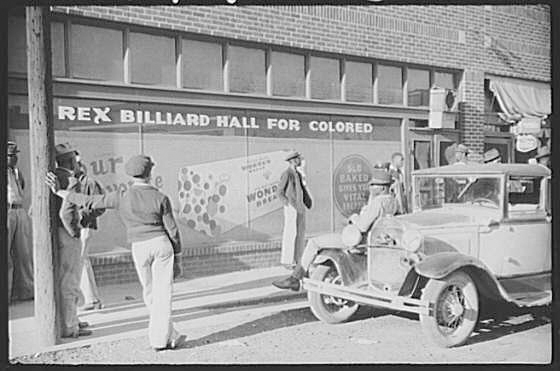

Discrimination based on race or ethnicity can take many forms, from unfair housing practices to biased hiring systems. Overt discrimination has long been part of U.S. history. In the late nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for business owners to hang signs that read, “Help Wanted: No Irish Need Apply.” And southern Jim Crow laws, with their “Whites Only” signs, exemplified overt discrimination that is not tolerated today.

However, we cannot erase discrimination from our culture just by enacting laws to abolish it. Even if a magic pill managed to eradicate racism from each individual’s psyche, society itself would maintain it. Sociologist Émile Durkheim calls racism a social fact, meaning that it does not require the actions of individuals to continue. The reasons for this are complex and relate to the educational, criminal, economic, and political systems that exist in our society.

For example, when a newspaper identifies by race individuals accused of a crime, it may enhance stereotypes of a certain minority. Another example of racist practices is racial steering, in which real estate agents direct prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race. Racist attitudes and beliefs are often more insidious and harder to pin down than specific racist practices.

Prejudice and discrimination can overlap and intersect in many ways. To illustrate, here are four examples of how prejudice and discrimination can occur. Unprejudiced nondiscriminators are open-minded, tolerant, and accepting individuals. Unprejudiced discriminators might be those who unthinkingly practice sexism in their workplace by not considering females for certain positions that have traditionally been held by men. Prejudiced nondiscriminators are those who hold racist beliefs but don’t act on them, such as a racist store owner who serves minority customers. Prejudiced discriminators include those who actively make disparaging remarks about others or who perpetrate hate crimes.

Discrimination also manifests in different ways. The scenarios above are examples of individual discrimination, but other types exist. Institutional discrimination occurs when a societal system has developed with embedded disenfranchisement of a group, such as the U.S. military’s historical nonacceptance of minority sexualities (the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy reflected this norm).

Institutional discrimination can also include the promotion of a group’s status, such as in the case of white privilege, which describes the benefits people receive simply by being part of the dominant group. While most white people are willing to admit that nonwhite people live with a set of disadvantages due to the color of their skin, very few are willing to acknowledge the benefits they receive.

Racial Tensions in the United States

The death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, illustrates racial tensions in the United States as well as the overlap between prejudice, discrimination, and institutional racism. On that day, Brown, a young unarmed black man, was killed by a white police officer named Darren Wilson. During the incident, Wilson directed Brown and his friend to walk on the sidewalk instead of in the street. While eyewitness accounts vary, they agree that an altercation occurred between Wilson and Brown. Wilson’s version has him shooting Brown in self-defense after Brown assaulted him, while Dorian Johnson, a friend of Brown also present at the time, claimed that Brown first ran away, then turned with his hands in the air to surrender, after which Wilson shot him repeatedly (Nobles and Bosman 2014). Three autopsies independently confirmed that Brown was shot six times (Lowery and Fears 2014).

The shooting focused attention on a number of race-related tensions in the United States. First, members of the predominantly black community viewed Brown’s death as the result of a white police officer racially profiling a black man (Nobles and Bosman 2014). In the days after, it was revealed that only three members of the town’s fifty-three-member police force were black (Nobles and Bosman 2014). The national dialogue shifted during the next few weeks, with some commentators pointing to the nationwide sedimentation of racial inequality and identifying redlining in Ferguson as a cause of the unbalanced racial composition in the community, local political establishments, and the police force (Bouie 2014). Redlining is the practice of routinely refusing mortgages for households and businesses located in predominately minority communities, while sedimentation of racial inequality describes the intergenerational impact of both practical and legalized racism that limits the abilities of black people to accumulate wealth.

Ferguson’s racial imbalance may explain in part why, even though in 2010 only about 63 percent of its population was black, in 2013 blacks were detained in 86 percent of stops, 92 percent of searches, and 93 percent of arrests (Missouri Attorney General’s Office 2014). In addition, de facto segregation in Ferguson’s schools, a race-based wealth gap, urban sprawl, and a black unemployment rate three times that of the white unemployment rate worsened existing racial tensions in Ferguson while also reflecting nationwide racial inequalities (Bouie 2014).

Multiple Identities

Prior to the twentieth century, racial intermarriage (referred to as miscegenation) was extremely rare, and in many places, illegal. In the later part of the twentieth century and in the twenty-first century, as Figure 11.2 shows, attitudes have changed for the better. While the sexual subordination of slaves did result in children of mixed race, these children were usually considered black, and therefore, property. There was no concept of multiple racial identities with the possible exception of Creole. Creole society developed in the port city of New Orleans, where a mixed-race culture grew from French and African inhabitants. Unlike in other parts of the country, “Creoles of color” had greater social, economic, and educational opportunities than most African Americans.

Increasingly during the modern era, the removal of miscegenation laws and a trend toward equal rights and legal protection against racism have steadily reduced the social stigma attached to racial exogamy (exogamy refers to marriage outside a person’s core social unit). It is now common for the children of racially mixed parents to acknowledge and celebrate their various ethnic identities. Golfer Tiger Woods, for instance, has Chinese, Thai, African American, Native American, and Dutch heritage; he jokingly refers to his ethnicity as “Cablinasian,” a term he coined to combine several of his ethnic backgrounds. While this is the trend, it is not yet evident in all aspects of our society. For example, the U.S. Census only recently added additional categories for people to identify themselves, such as non-white Hispanics. A growing number of people chose multiple races to describe themselves on the 2010 Census, paving the way for the 2020 Census to provide yet more choices.

7.3 Theories of Race and Ethnicity

Learning Objectives

- Describe how major sociological perspectives view race and ethnicity

- Identify examples of culture of prejudice

Theoretical Perspectives

We can examine issues of race and ethnicity through three major sociological perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. As you read through these theories, ask yourself which one makes the most sense and why. Do we need more than one theory to explain racism, prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination?

Functionalism

In the view of functionalism, racial and ethnic inequalities must have served an important function in order to exist as long as they have. This concept, of course, is problematic. How can racism and discrimination contribute positively to society? A functionalist might look at “functions” and “dysfunctions” caused by racial inequality. Nash (1964) focused his argument on the way racism is functional for the dominant group, for example, suggesting that racism morally justifies a racially unequal society. Consider the way slave owners justified slavery in the antebellum South, by suggesting black people were fundamentally inferior to white people and preferred slavery to freedom.

Another way to apply the functionalist perspective to racism is to discuss the way racism can contribute positively to the functioning of society by strengthening bonds between in-group members through the ostracism of out-group members. Consider how a community might increase its solidarity by refusing to allow outsiders access. On the other hand, Rose (1951) suggested that dysfunctions associated with racism include the failure to take advantage of the talent in the subjugated group and that society must divert from other purposes the time and effort needed to maintain artificially constructed racial boundaries. Consider how much money, time, and effort went toward maintaining separate and unequal educational systems prior to the civil rights movement.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theories are often applied to inequalities of gender, social class, education, race, and ethnicity. A conflict theory perspective of U.S. history would examine the numerous past and current struggles between the white ruling class and racial and ethnic minorities, noting specific conflicts that have arisen when the dominant group perceived a threat from the minority group. In the late nineteenth century, the rising power of black Americans after the Civil War resulted in draconian Jim Crow laws that severely limited black political and social power. For example, Vivien Thomas (1910–1985), the black surgical technician who helped develop the groundbreaking surgical technique that saves the lives of “blue babies” was classified as a janitor for many years, and paid as such, despite the fact that he was conducting complicated surgical experiments. The years since the Civil War have shown a pattern of attempted disenfranchisement, with gerrymandering and voter suppression efforts aimed at predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) further developed the intersection theory, originally articulated in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes. When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped, for example, by our gender and class. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a white woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on a poor Asian woman, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and her ethnic status.

Interactionism

For symbolic interactionists, race and ethnicity provide strong symbols as sources of identity. In fact, some interactionists propose that the symbols of race, not race itself, are what lead to racism. Famed interactionist Herbert Blumer (1958) suggested that racial prejudice is formed through interactions between members of the dominant group; without these interactions, individuals in the dominant group would not hold racist views. These interactions contribute to an abstract picture of the subordinate group that allows the dominant group to support its view of the subordinate group and thus maintains the status quo. An example of this might be an individual whose beliefs about a particular group are based on images conveyed in popular media, and those are unquestionably believed because the individual has never personally met a member of that group. Another way to apply the interactionist perspective is to look at how people define their races and the races of others. As we discussed in relation to the social construction of race, since some people who claim a white identity have a greater amount of skin pigmentation than some people who claim a black identity, how did they come to define themselves as black or white?

Culture of Prejudice

Culture of prejudice refers to the theory that prejudice is embedded in our culture. We grow up surrounded by images of stereotypes and casual expressions of racism and prejudice. Consider the casually racist imagery on grocery store shelves or the stereotypes that fill popular movies and advertisements. It is easy to see how someone living in the Northeastern United States, who may know no Mexican Americans personally, might gain a stereotyped impression from such sources as Speedy Gonzalez or Taco Bell’s talking chihuahua. Because we are all exposed to these images and thoughts, it is impossible to know to what extent they have influenced our thought processes.

7.4 Intergroup Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Explain different intergroup relations in terms of their relative levels of tolerance

- Give historical and/or contemporary examples of each type of intergroup relation

Intergroup relations (relationships between different groups of people) range along a spectrum between tolerance and intolerance. The most tolerant form of intergroup relations is pluralism, in which no distinction is made between minority and majority groups, but instead, there’s equal standing. At the other end of the continuum are amalgamations, expulsions, and even genocide—stark examples of intolerant intergroup relations.

Genocide

Genocide, the deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group, is the most toxic intergroup relationship. Historically, we can see that genocide has included both the intent to exterminate a group and the function of exterminating a group, intentional or not.

Possibly the most well-known case of genocide is Hitler’s attempt to exterminate the Jewish people in the first part of the twentieth century. Also known as the Holocaust, the explicit goal of Hitler’s “Final Solution” was the eradication of European Jewry, as well as the destruction of other minority groups such as Catholics, people with disabilities, and homosexuals. With forced emigration, concentration camps, and mass executions in gas chambers, Hitler’s Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of 12 million people, 6 million of whom were Jewish. Hitler’s intent was clear, and the high Jewish death toll certainly indicates that Hitler and his regime committed genocide. But how do we understand genocide that is not so overt and deliberate?

The treatment of aboriginal Australians is also an example of genocide committed against indigenous people. Historical accounts suggest that between 1824 and 1908, white settlers killed more than 10,000 native aborigines in Tasmania and Australia (Tatz 2006). Another example is the European colonization of North America. Some historians estimate that Native American populations dwindled from approximately 12 million people in the year 1500 to barely 237,000 by the year 1900 (Lewy 2004). European settlers coerced American Indians off their own lands, often causing thousands of deaths in forced removals, such as occurred in the Cherokee or Potawatomi Trail of Tears. Settlers also enslaved Native Americans and forced them to give up their religious and cultural practices. But the major cause of Native American death was neither slavery nor war nor forced removal: it was the introduction of European diseases and Indians’ lack of immunity to them. Smallpox, diphtheria, and measles flourished among indigenous American tribes who had no exposure to the diseases and no ability to fight them. Quite simply, these diseases decimated the tribes. How planned this genocide was remained a topic of contention. Some argue that the spread of disease was an unintended effect of conquest, while others believe it was intentional, citing rumors of smallpox-infected blankets being distributed as “gifts” to tribes.

Genocide is not just a historical concept; it is practiced today. Recently, ethnic and geographic conflicts in the Darfur region of Sudan have led to hundreds of thousands of deaths. As part of an ongoing land conflict, the Sudanese government and their state-sponsored Janjaweed militia have led a campaign of killing, forced displacement, and systematic rape of the Darfuri people. Although a treaty was signed in 2011, the peace is fragile.

Expulsion

Expulsion refers to a subordinate group being forced, by a dominant group, to leave a certain area or country. As seen in the examples of the Trail of Tears and the Holocaust, expulsion can be a factor in genocide. However, it can also stand on its own as destructive group interaction. Expulsion has often occurred historically on an ethnic or racial basis. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, after the Japanese government’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The Order authorized the establishment of internment camps for anyone with as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry (i.e., one great-grandparent who was Japanese). Over 120,000 legal Japanese residents and Japanese U.S. citizens, many of them children, were held in these camps for up to four years, despite the fact that there was never any evidence of collusion or espionage. (In fact, many Japanese Americans continued to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by serving in the U.S. military during the War.) In the 1990s, the U.S. executive branch issued a formal apology for this expulsion; reparation efforts continue today.

Here’s a question: Could gentrification be considered a form of expulsion?

Segregation

Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in the workplace and social functions. It is important to distinguish between de jure segregation (segregation that is enforced by law) and de facto segregation (segregation that occurs without laws but because of other factors). A stark example of de jure segregation is the apartheid movement of South Africa, which existed from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid, black South Africans were stripped of their civil rights and forcibly relocated to areas that segregated them physically from their white compatriots. Only after decades of degradation, violent uprisings, and international advocacy was apartheid finally abolished.

De jure segregation occurred in the United States for many years after the Civil War. During this time, many former Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws that required segregated facilities for blacks and whites. These laws were codified in 1896’s landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. For the next five decades, blacks were subjected to legalized discrimination, and forced to live, work, and go to school in separate—but unequal—facilities. It wasn’t until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education case that the Supreme Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” thus ending de jure segregation in the United States.

De facto segregation, however, cannot be abolished by any court mandate. Segregation is still alive and well in the United States, with different racial or ethnic groups often segregated by neighborhood, borough, or parish. Sociologists use segregation indices to measure the racial segregation of different races in different areas. The indices employ a scale from zero to 100, where zero is the most integrated and 100 is the least. In the New York metropolitan area, for instance, the black-white segregation index was seventy-nine for the years 2005–2009. This means that 79 percent of either blacks or whites would have to move in order for each neighborhood to have the same racial balance as the whole metro region (Population Studies Center 2010).

Pluralism

Pluralism is represented by the ideal of the United States as a “salad bowl”: a great mixture of different cultures where each culture retains its own identity and yet adds to the flavor of the whole. True pluralism is characterized by mutual respect on the part of all cultures, both dominant and subordinate, creating a multicultural environment of acceptance. In reality, true pluralism is a difficult goal to reach. In the United States, the mutual respect required by pluralism is often missing, and the nation’s past pluralist model of a melting pot posits a society where cultural differences aren’t embraced as much as erased.

Assimilation

Assimilation describes the process by which a minority individual or group gives up its own identity by taking on the characteristics of the dominant culture. In the United States, which has a history of welcoming and absorbing immigrants from different lands, assimilation has been a function of immigration.

Most people in the United States have immigrant ancestors. In relatively recent history, between 1890 and 1920, the United States became home to around 24 million immigrants. In the decades since then, further waves of immigrants have come to these shores and have eventually been absorbed into U.S. culture, sometimes after facing extended periods of prejudice and discrimination. Assimilation may lead to the loss of the minority group’s cultural identity as they become absorbed into the dominant culture, but assimilation has minimal to no impact on the majority group’s cultural identity.

Some groups may keep only symbolic gestures of their original ethnicity. For instance, many Irish Americans may celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day, many Hindu Americans enjoy the Diwali festival, and many Mexican Americans may celebrate Cinco de Mayo (a May 5 acknowledgment of Mexico’s victory at the 1862 Battle of Puebla). However, for the rest of the year, other aspects of their originating culture may be forgotten.

Assimilation is antithetical to the “salad bowl” created by pluralism; rather than maintaining their own cultural flavor, subordinate cultures give up their own traditions in order to conform to their new environment. Sociologists measure the degree to which immigrants have assimilated to a new culture with four benchmarks: socioeconomic status, spatial concentration, language assimilation, and intermarriage. When faced with racial and ethnic discrimination, it can be difficult for new immigrants to fully assimilate. Language assimilation, in particular, can be a formidable barrier, limiting employment and educational options and therefore constraining growth in socioeconomic status.

Amalgamation

Amalgamation is the process by which a minority group and a majority group combine to form a new group. Amalgamation creates the classic “melting pot” analogy; unlike the “salad bowl,” in which each culture retains its individuality, the “melting pot” ideal sees the combination of cultures that results in a new culture entirely.

Amalgamation, also known as miscegenation, is achieved through intermarriage between races. In the United States, antimiscegenation laws flourished in the South during the Jim Crow era. It wasn’t until 1967’s Loving v. Virginia that the last antimiscegenation law was struck from the books, making these laws unconstitutional.

7.5 Race and Ethnicity in the United States

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the different experiences of various ethnic groups in the United States

- Apply theories of intergroup relations, race, and ethnicity to different subordinate groups

When colonists came to the New World, they found a land that did not need “discovering” since it was already occupied. While the first wave of immigrants came from Western Europe, eventually the bulk of people entering North America was from Northern Europe, then Eastern Europe, then Latin America, and Asia. And let us not forget the forced immigration of African slaves. Most of these groups underwent a period of disenfranchisement in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy before they managed (for those who could) to achieve social mobility. Today, our society is multicultural, although the extent to which this multiculturality is embraced varies, and the many manifestations of multiculturalism carry significant political repercussions. The sections below will describe how several groups became part of U.S. society, discuss the history of intergroup relations for each faction, and assess each group’s status today.

Native Americans

The only nonimmigrant ethnic group in the United States, Native Americans once numbered in the millions but by 2010 made up only 0.9 percent of the U.S. populace; see above (U.S. Census 2010). Currently, about 2.9 million people identify themselves as Native American alone, while an additional 2.3 million identify them as Native American mixed with another ethnic group (Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel 2012).

How and Why They Came

The earliest immigrants to America arrived millennia before European immigrants. Dates of the migration are debated with estimates ranging from between 45,000 and 12,000 BCE. It is thought that early Indians migrated to this new land in search of big game to hunt, which they found in huge herds of grazing herbivores in the Americas. Over the centuries and then the millennia, Native American culture blossomed into an intricate web of hundreds of interconnected tribes, each with its own customs, traditions, languages, and religions.

History of Intergroup Relations

Native American culture prior to European settlement is referred to as Pre-Columbian: that is, prior to the coming of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Mistakenly believing that he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus named the indigenous people “Indians,” a name that has persisted for centuries despite being a geographical misnomer and one used to blanket 500 distinct groups who each have their own languages and traditions.

The history of intergroup relations between European colonists and Native Americans is a brutal one. As discussed in the section on genocide, the effect of European settlement of the Americans was to nearly destroy the indigenous population. And although Native Americans’ lack of immunity to European diseases caused the most deaths, overt mistreatment of Native Americans by Europeans was devastating as well.

From the first Spanish colonists to the French, English, and Dutch who followed, European settlers took what land they wanted and expanded across the continent at will. If indigenous people tried to retain their stewardship of the land, Europeans fought them off with superior weapons. A key element of this issue is the indigenous view of land and land ownership. Most tribes considered the earth a living entity whose resources they were stewards of, the concepts of land ownership and conquest didn’t exist in Native American society. Europeans’ domination of the Americas was indeed a conquest; one scholar points out that Native Americans are the only minority group in the United States whose subordination occurred purely through conquest by the dominant group (Marger 1993).

After the establishment of the United States government, discrimination against Native Americans was codified and formalized in a series of laws intended to subjugate them and keep them from gaining any power. Some of the most impactful laws are as follows:

- The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced the relocation of any native tribes east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river.

- The Indian Appropriation Acts funded further removals and declared that no Indian tribe could be recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with which the U.S. government would have to make treaties. This made it even easier for the U.S. government to take land it wanted.

- The Dawes Act of 1887 reversed the policy of isolating Native Americans on reservations, instead forcing them onto individual properties that were intermingled with white settlers, thereby reducing their capacity for power as a group.

Native American culture was further eroded by the establishment of Indian boarding schools in the late nineteenth century. These schools, run by both Christian missionaries and the United States government, had the express purpose of “civilizing” Native American children and assimilating them into white society. The boarding schools were located off-reservation to ensure that children were separated from their families and culture. Schools forced children to cut their hair, speak English, and practice Christianity. Physical and sexual abuses were rampant for decades; only in 1987 did the Bureau of Indian Affairs issue a policy on sexual abuse in boarding schools. Some scholars argue that many of the problems that Native Americans face today result from almost a century of mistreatment at these boarding schools.

Current Status

The eradication of Native American culture continued until the 1960s, when Native Americans were able to participate in and benefit from the civil rights movement. The Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 guaranteed Indian tribes most of the rights of the United States Bill of Rights. New laws like the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 and the Education Assistance Act of the same year recognized tribal governments and gave them more power. Indian boarding schools have dwindled to only a few, and Native American cultural groups are striving to preserve and maintain old traditions to keep them from being lost forever.

However, Native Americans (some of whom now wished to be called American Indians so as to avoid the “savage” connotations of the term “native”) still suffer the effects of centuries of degradation. Long-term poverty, inadequate education, cultural dislocation, and high rates of unemployment contribute to Native American populations falling to the bottom of the economic spectrum. Native Americans also suffer disproportionately with lower life expectancies than most groups in the United States.

African Americans

As discussed in the section on race, the term African American can be a misnomer for many individuals. Many people with dark skin may have their more recent roots in Europe or the Caribbean, seeing themselves as Dominican American or Dutch American. Further, actual immigrants from Africa may feel that they have more of a claim to the term African American than those who are many generations removed from ancestors who originally came to this country. This section will focus on the experience of the slaves who were transported from Africa to the United States, and their progeny. Currently, the U.S. Census Bureau (2014) estimates that 13.2 percent of the United States’ population is black.

How and Why They Came

If Native Americans are the only minority group whose subordinate status occurred by conquest, African Americans are the exemplar minority group in the United States whose ancestors did not come here by choice. A Dutch sea captain brought the first Africans to the Virginia colony of Jamestown in 1619 and sold them as indentured servants. This was not an uncommon practice for either blacks or whites, and indentured servants were in high demand. For the next century, black and white indentured servants worked side by side. But the growing agricultural economy demanded greater and cheaper labor, and by 1705, Virginia passed the slave codes declaring that any foreign-born non-Christian could be a slave, and that slaves were considered property.

The next 150 years saw the rise of U.S. slavery, with black Africans being kidnapped from their own lands and shipped to the New World on the trans-Atlantic journey known as the Middle Passage. Once in the Americas, the black population grew until U.S.-born blacks outnumbered those born in Africa. But colonial (and later, U.S.) slave codes declared that the child of a slave was a slave, so the slave class was created. By 1808, the slave trade was internal in the United States, with slaves being bought and sold across state lines like livestock. In 1808, during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, Congress prohibited the international importation of humans to be used as slaves.

History of Intergroup Relations

There is no starker illustration of the dominant-subordinate group relationship than that of slavery. In order to justify their severely discriminatory behavior, slaveholders and their supporters had to view blacks as innately inferior. Slaves were denied even the most basic rights of citizenship, a crucial factor for slaveholders and their supporters. Slavery poses an excellent example of conflict theory’s perspective on race relations; the dominant group needed complete control over the subordinate group in order to maintain its power. Whippings, executions, rapes, denial of schooling and health care were all permissible and widely practiced.

Slavery eventually became an issue over which the nation divided into geographically and ideologically distinct factions, leading to the Civil War. And while the abolition of slavery on moral grounds was certainly a catalyst to war, it was not the only driving force. Students of U.S. history will know that the institution of slavery was crucial to the Southern economy, whose production of crops like rice, cotton, and tobacco relied on the virtually limitless and cheap labor that slavery provided. In contrast, the North didn’t benefit economically from slavery, resulting in an economic disparity tied to racial/political issues.

A century later, the civil rights movement was characterized by boycotts, marches, sit-ins, and freedom rides: demonstrations by a subordinate group that would no longer willingly submit to domination. The major blow to America’s formally institutionalized racism was the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This Act, which is still followed today, banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Some sociologists, however, would argue that institutionalized racism persists.

Current Status

Although government-sponsored, formalized discrimination against African Americans has been outlawed, true equality does not yet exist. The National Urban League’s 2011 Equality Index reports that blacks’ overall equality level with whites has dropped in the past year, from 71.5 percent to 71.1 percent in 2010. The Index, which has been published since 2005, notes a growing trend of increased inequality with whites, especially in the areas of unemployment, insurance coverage, and incarceration. Blacks also trail whites considerably in the areas of economics, health, and education.

To what degree do racism and prejudice contribute to this continued inequality? The answer is complex. 2008 saw the election of this country’s first African American president: Barack Hussein Obama. Despite being popularly identified as black, we should note that President Obama is of a mixed background that is equally white, and although all presidents have been publicly mocked at times (Gerald Ford was depicted as a klutz, Bill Clinton as someone who could not control his libido), a startling percentage of the critiques of Obama have been based on his race. The most blatant of these was the controversy over his birth certificate, where the “birther” movement questioned his citizenship and right to hold office. Although blacks have come a long way from slavery, the echoes of centuries of disempowerment are still evident.

Asian Americans

Like many groups this section discusses, Asian Americans represent a great diversity of cultures and backgrounds. The experience of a Japanese American whose family has been in the United States for three generations will be drastically different from a Laotian American who has only been in the United States for a few years. This section primarily discusses Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese immigrants and shows the differences between their experiences. The most recent estimate from the U.S. Census Bureau (2014) suggest about 5.3 percent of the population identify themselves as Asian.

How and Why They Came

The national and ethnic diversity of Asian American immigration history is reflected in the variety of their experiences in joining U.S. society. Asian immigrants have come to the United States in waves, at different times, and for different reasons.

The first Asian immigrants to come to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century were Chinese. These immigrants were primarily men whose intention was to work for several years in order to earn incomes to support their families in China. Their main destination was the American West, where the Gold Rush was drawing people with its lure of abundant money. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad was underway at this time, and the Central Pacific section hired thousands of migrant Chinese men to complete the laying of rails across the rugged Sierra Nevada mountain range. Chinese men also engaged in other manual labor like mining and agricultural work. The work was grueling and underpaid, but like many immigrants, they persevered.

Japanese immigration began in the 1880s, on the heels of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Many Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii to participate in the sugar industry; others came to the mainland, especially to California. Unlike the Chinese, however, the Japanese had a strong government that negotiated with the U.S. government to ensure the well-being of their immigrants. Japanese men were able to bring their wives and families to the United States, and were thus able to produce second- and third-generation Japanese Americans more quickly than their Chinese counterparts.

The most recent large-scale Asian immigration came from Korea and Vietnam and largely took place during the second half of the twentieth century. While Korean immigration has been fairly gradual, Vietnamese immigration occurred primarily post-1975, after the fall of Saigon and the establishment of restrictive communist policies in Vietnam. Whereas many Asian immigrants came to the United States to seek better economic opportunities, Vietnamese immigrants came as political refugees, seeking asylum from harsh conditions in their homeland. The Refugee Act of 1980 helped them to find a place to settle in the United States.

History of Intergroup Relations

Chinese immigration came to an abrupt end with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This act was a result of anti-Chinese sentiment burgeoned by a depressed economy and loss of jobs. White workers blamed Chinese migrants for taking jobs, and the passage of the Act meant the number of Chinese workers decreased. Chinese men did not have the funds to return to China or to bring their families to the United States, so they remained physically and culturally segregated in the Chinatowns of large cities. Later legislation, the Immigration Act of 1924, further curtailed Chinese immigration. The Act included the race-based National Origins Act, which was aimed at keeping U.S. ethnic stock as undiluted as possible by reducing “undesirable” immigrants. It was not until after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that Chinese immigration again increased, and many Chinese families were reunited.

Although Japanese Americans have deep, long-reaching roots in the United States, their history here has not always been smooth. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 was aimed at them and other Asian immigrants, and it prohibited aliens from owning land. An even uglier action was the Japanese internment camps of World War II, discussed earlier as an illustration of expulsion.

Current Status

Asian Americans certainly have been subject to their share of racial prejudice, despite the seemingly positive stereotype as the model minority. The model minority stereotype is applied to a minority group that is seen as reaching significant educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without challenging the existing establishment.

This stereotype is typically applied to Asian groups in the United States, and it can result in unrealistic expectations, by putting a stigma on members of this group that do not meet the expectations. Stereotyping all Asians as smart and capable can also lead to a lack of much-needed government assistance and to educational and professional discrimination.

Hispanic Americans

Hispanic Americans have a wide range of backgrounds and nationalities. The segment of the U.S. population that self-identifies as Hispanic in 2013 was recently estimated at 17.1 percent of the total (U.S. Census Bureau 2014). According to the 2010 U.S. Census, about 75 percent of the respondents who identify as Hispanic report being of Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Cuban origin. Of the total Hispanic group, 60 percent reported as Mexican, 44 percent reported as Cuban, and 9 percent reported as Puerto Rican. Remember that the U.S. Census allows people to report as being more than one ethnicity.

Not only are there wide differences among the different origins that make up the Hispanic American population, but there are also different names for the group itself. The 2010 U.S. Census states that “Hispanic” or “Latino” refers to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.” There have been some disagreements over whether Hispanic or Latino is the correct term for a group this diverse, and whether it would be better for people to refer to themselves as being of their origin specifically, for example, Mexican American or Dominican American. This section will compare the experiences of Mexican Americans and Cuban Americans.

How and Why They Came

Mexican Americans form the largest Hispanic subgroup and also the oldest. Mexican migration to the United States started in the early 1900s in response to the need for cheap agricultural labor. Mexican migration was often circular; workers would stay for a few years and then go back to Mexico with more money than they could have made in their country of origin. The length of Mexico’s shared border with the United States has made immigration easier than for many other immigrant groups.

Cuban Americans are the second-largest Hispanic subgroup, and their history is quite different from that of Mexican Americans. The main wave of Cuban immigration to the United States started after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959 and reached its crest with the Mariel boatlift in 1980. Castro’s Cuban Revolution ushered in an era of communism that continues to this day. To avoid having their assets seized by the government, many wealthy and educated Cubans migrated north, generally to the Miami area.

History of Intergroup Relations

For several decades, Mexican workers crossed the long border into the United States, both legally and illegally, to work in the fields that provided produce for the developing United States. Western growers needed a steady supply of labor, and the 1940s and 1950s saw the official federal Bracero Program (bracero is Spanish for strong-arm) that offered protection to Mexican guest workers. Interestingly, 1954 also saw the enactment of “Operation Wetback,” which deported thousands of illegal Mexican workers. From these examples, we can see the U.S. treatment of immigration from Mexico has been ambivalent at best.

Sociologist Douglas Massey (2006) suggests that although the average standard of living than in Mexico may be lower in the United States, it is not so low as to make permanent migration the goal of most Mexicans. However, the strengthening of the border that began with 1986’s Immigration Reform and Control Act has made one-way migration the rule for most Mexicans. Massey argues that the rise of illegal one-way immigration of Mexicans is a direct outcome of the law that was intended to reduce it.

Cuban Americans, perhaps because of their relative wealth and education level at the time of immigration, have fared better than many immigrants. Further, because they were fleeing a Communist country, they were given refugee status and offered protection and social services. The Cuban Migration Agreement of 1995 has curtailed legal immigration from Cuba, leading many Cubans to try to immigrate illegally by boat. According to a 2009 report from the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. government applies a “wet foot/dry foot” policy toward Cuban immigrants; Cubans who are intercepted while still at sea will be returned to Cuba, while those who reach the shore will be permitted to stay in the United States.

Current Status

Mexican Americans, especially those who are here illegally, are at the center of a national debate about immigration. Myers (2007) observes that no other minority group (except the Chinese) has immigrated to the United States in such an environment of illegality. He notes that in some years, three times as many Mexican immigrants may have entered the United States illegally as those who arrived legally. It should be noted that this is due to enormous disparity of economic opportunity on two sides of an open border, not because of any inherent inclination to break laws. In his report, “Measuring Immigrant Assimilation in the United States,” Jacob Vigdor (2008) states that Mexican immigrants experience relatively low rates of economic and civic assimilation. He further suggests that “the slow rates of economic and civic assimilation set Mexicans apart from other immigrants, and may reflect the fact that the large numbers of Mexican immigrants residing in the United States illegally have few opportunities to advance themselves along these dimensions.”

By contrast, Cuban Americans are often seen as a model minority group within the larger Hispanic group. Many Cubans had higher socioeconomic status when they arrived in this country, and their anti-Communist agenda has made them welcome refugees to this country. In south Florida, especially, Cuban Americans are active in local politics and professional life. As with Asian Americans, however, being a model minority can mask the issue of powerlessness that these minority groups face in U.S. society.

Arab Americans

If ever a category was hard to define, the various groups lumped under the name “Arab American” is it. After all, Hispanic Americans or Asian Americans are so designated because of their counties of origin. But for Arab Americans, their country of origin—Arabia—has not existed for centuries. In addition, Arab Americans represent all religious practices, despite the stereotype that all Arabic people practice Islam. As Myers (2007) asserts, not all Arabs are Muslim, and not all Muslims are Arab, complicating the stereotype of what it means to be an Arab American. Geographically, the Arab region comprises the Middle East and parts of northern Africa. People whose ancestry lies in that area or who speak primarily Arabic may consider themselves Arabs.

The U.S. Census has struggled with the issue of Arab identity. The 2010 Census, as in previous years, did not offer an “Arab” box to check under the question of race. Individuals who want to be counted as Arabs had to check the box for “Some other race” and then write in their race. However, when the Census data is tallied, they will be marked as white. This is problematic, however, denying Arab Americans opportunities for federal assistance. According to the best estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau, the Arabic population in the United States grew from 850,000 in 1990 to 1.2 million in 2000, an increase of .07 percent (Asi and Beaulieu 2013).

Why They Came

The first Arab immigrants came to this country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were predominantly Syrian, Lebanese, and Jordanian Christians, and they came to escape persecution and to make a better life. These early immigrants and their descendants, who were more likely to think of themselves as Syrian or Lebanese than Arab, represent almost half of the Arab American population today (Myers 2007). Restrictive immigration policies from the 1920s until 1965 curtailed all immigration, but Arab immigration since 1965 has been steady. Immigrants from this time period have been more likely to be Muslim and more highly educated, escaping political unrest and looking for better opportunities.

History of Intergroup Relations

Relations between Arab Americans and the dominant majority have been marked by mistrust, misinformation, and deeply entrenched beliefs. Helen Samhan of the Arab American Institute suggests that Arab-Israeli conflicts in the 1970s contributed significantly to cultural and political anti-Arab sentiment in the United States (2001). The United States has historically supported the State of Israel, while some Middle Eastern countries deny the existence of the Israeli state. Disputes over these issues have involved Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine.

As is often the case with stereotyping and prejudice, the actions of extremists come to define the entire group, regardless of the fact that most U.S. citizens with ties to the Middle Eastern community condemn terrorist actions, as do most inhabitants of the Middle East. Would it be fair to judge all Catholics by the events of the Inquisition? Of course, the United States was deeply affected by the events of September 11, 2001. This event has left a deep scar on the American psyche, and it has fortified anti-Arab sentiment for a large percentage of Americans. In the first month after 9/11, hundreds of hate crimes were perpetrated against people who looked like they might be of Arab descent.

Current Status

Although the rate of hate crimes against Arab Americans has slowed, Arab Americans are still victims of racism and prejudice. Racial profiling has proceeded against Arab Americans as a matter of course since 9/11. Particularly when engaged in air travel, being young and Arab-looking is enough to warrant a special search or detainment. This Islamophobia (irrational fear of or hatred against Muslims) does not show signs of abating. Scholars noted that white domestic terrorists like Timothy McVeigh, who detonated a bomb at an Oklahoma courthouse in 1995, have not inspired similar racial profiling or hate crimes against whites.

White Ethnic Americans

As we have seen, there is no minority group that fits easily in a category or that can be described simply. While sociologists believe that individual experiences can often be understood in light of their social characteristics (such as race, class, or gender), we must balance this perspective with awareness that no two individuals’ experiences are alike. Making generalizations can lead to stereotypes and prejudice. The same is true for white ethnic Americans, who come from diverse backgrounds and have had a great variety of experiences. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2014), 77.7 percent of U.S. adults currently identify themselves as white alone. In this section, we will focus on German, Irish, Italian, and Eastern European immigrants.

Why They Came

White ethnic Europeans formed the second and third great waves of immigration, from the early nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. They joined a newly minted United States that was primarily made up of white Protestants from England. While most immigrants came searching for a better life, their experiences were not all the same.

The first major influx of European immigrants came from Germany and Ireland, starting in the 1820s. Germans came both for economic opportunity and to escape political unrest and military conscription, especially after the Revolutions of 1848. Many German immigrants of this period were political refugees: liberals who wanted to escape from an oppressive government. They were well-off enough to make their way inland, and they formed heavily German enclaves in the Midwest that exist to this day.

The Irish immigrants of the same time period were not always as well off financially, especially after the Irish Potato Famine of 1845. Irish immigrants settled mainly in the cities of the East Coast, where they were employed as laborers and where they faced significant discrimination.

German and Irish immigration continued into the late 19th century and earlier 20th century, at which point the numbers for Southern and Eastern European immigrants started growing as well. Italians, mainly from the Southern part of the country, began arriving in large numbers in the 1890s. Eastern European immigrants—people from Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, and Austria-Hungary—started arriving around the same time. Many of these Eastern Europeans were peasants forced into a hardscrabble existence in their native lands; political unrest, land shortages, and crop failures drove them to seek better opportunities in the United States. The Eastern European immigration wave also included Jewish people escaping pogroms (anti-Jewish massacres) of Eastern Europe and the Pale of Settlement in what was then Poland and Russia.

History of Intergroup Relations

In a broad sense, German immigrants were not victimized to the same degree as many of the other subordinate groups this section discusses. While they may not have been welcomed with open arms, they were able to settle in enclaves and establish roots. A notable exception to this was during the lead up to World War I and through World War II, when anti-German sentiment was virulent.

Irish immigrants, many of whom were very poor, were more of an underclass than the Germans. In Ireland, the English had oppressed the Irish for centuries, eradicating their language and culture and discriminating against their religion (Catholicism). Although the Irish had a larger population than the English, they were a subordinate group. This dynamic reached into the new world, where Anglo Americans saw Irish immigrants as a race apart: dirty, lacking ambition, and suitable for only the most menial jobs. In fact, Irish immigrants were subject to criticism identical to that with which the dominant group characterized African Americans. By necessity, Irish immigrants formed tight communities segregated from their Anglo neighbors.

The later wave of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe was also subject to intense discrimination and prejudice. In particular, the dominant group—which now included second- and third-generation Germans and Irish—saw Italian immigrants as the dregs of Europe and worried about the purity of the American race (Myers 2007). Italian immigrants lived in segregated slums in Northeastern cities, and in some cases were even victims of violence and lynchings similar to what African Americans endured. They worked harder and were paid less than other workers, often doing the dangerous work that other laborers were reluctant to take on.

Current Status

The U.S. Census from 2008 shows that 16.5 percent of respondents reported being of German descent: the largest group in the country. For many years, German Americans endeavored to maintain a strong cultural identity, but they are now culturally assimilated into the dominant culture.

There are now more Irish Americans in the United States than there are Irish in Ireland. One of the country’s largest cultural groups, Irish Americans have slowly achieved acceptance and assimilation into the dominant group.

Myers (2007) states that Italian Americans’ cultural assimilation is “almost complete, but with remnants of ethnicity.” The presence of “Little Italy” neighborhoods—originally segregated slums where Italians congregated in the nineteenth century—exist today. While tourists flock to the saints’ festivals in Little Italies, most Italian Americans have moved to the suburbs at the same rate as other white groups.

Key Terms:

amalgamation—the process by which a minority group and a majority group combine to form a new group

assimilation—the process by which a minority individual or group takes on the characteristics of the dominant culture

colorism—the belief that one type of skin tone is superior or inferior to another within a racial group

culture of prejudice—the theory that prejudice is embedded in our culture

discrimination—prejudiced action against a group of people

dominant group—a group of people who have more power in society than any of the subordinate groups

ethnicity—shared culture, which may include heritage, language, religion, and more

expulsion—the act of a dominant group forcing a subordinate group to leave a certain area or even the country

genocide—the deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group

institutional racism—racism embedded in social institutions

intersection theory—the theory that suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes

minority group—any group of people who are singled out from the others for differential and unequal treatment

model minority—the stereotype applied to a minority group that is seen as reaching higher educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without protest against the majority establishment

pluralism—the ideal of the United States as a “salad bowl:” a mixture of different cultures where each culture retains its own identity and yet adds to the “flavor” of the whole

prejudice—biased thought based on flawed assumptions about a group of people

racial profiling—the use by law enforcement of race alone to determine whether to stop and detain someone

racial steering—the act of real estate agents directing prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race

racism—a set of attitudes, beliefs, and practices that are used to justify the belief that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others

redlining—the practice of routinely refusing mortgages for households and businesses located in predominately minority communities

scapegoat theory—a theory that suggests that the dominant group will displace its unfocused aggression onto a subordinate group

sedimentation of racial inequality—the intergenerational impact of de facto and de jure racism that limits the abilities of black people to accumulate wealth

segregation—the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in the workplace and social functions

social construction of race—the school of thought that race is not biologically identifiable

stereotypes—oversimplified ideas about groups of people

subordinate group—a group of people who have less power than the dominant group

white privilege—the benefits people receive simply by being part of the dominant group

Section Summaries

7.1 Racial, Ethnic, and Minority Groups

Race is fundamentally a social construct. Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture and national origin. Minority groups are defined by their lack of power.

7.2 Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Stereotypes are oversimplified ideas about groups of people. Prejudice refers to thoughts and feelings, while discrimination refers to actions. Racism refers to the belief that one race is inherently superior or inferior to other races.

7.3 Theories of Race and Ethnicity

Functionalist views of race study the roles dominant and subordinate groups play in creating a stable social structure. Conflict theorists examine power disparities and struggles between various racial and ethnic groups. Interactionists see race and ethnicity as important sources of individual identity and social symbolism. The concept of a culture of prejudice recognizes that all people are subject to stereotypes that are ingrained in their culture.

7.4 Intergroup Relationships

Intergroup relations range from a tolerant approach of pluralism to intolerance as severe as genocide. In pluralism, groups retain their own identity. In assimilation, groups conform to the identity of the dominant group. In amalgamation, groups combine to form a new group identity.

7.5 Race and Ethnicity in the United States

The history of the U.S. people contains an infinite variety of experiences that sociologists understand follow patterns. From the indigenous people who first inhabited these lands to the waves of immigrants over the past 500 years, migration is an experience with many shared characteristics. Most groups have experienced various degrees of prejudice and discrimination as they have gone through the process of assimilation.

Section Quizzes

7.1 Racial, Ethnic, and Minority Groups

1. The racial term “African American” can refer to:

- a black person living in the United States

- people whose ancestors came to the United States through the slave trade

- a white person who originated in Africa and now lives in the United States

- any of the above

2. What is the one defining feature of a minority group?

- Self-definition

- Numerical minority

- Lack of power

- Strong cultural identity

3. Ethnicity describes shared:

- beliefs

- language

- religion

- any of the above

4. Which of the following is an example of a numerical majority being treated as a subordinate group?

- Jewish people in Germany

- Creoles in New Orleans

- White people in Brazil

- Blacks under apartheid in South Africa

5. Scapegoat theory shows that:

- subordinate groups blame dominant groups for their problems

- dominant groups blame subordinate groups for their problems

- some people are predisposed to prejudice

- all of the above

7.2 Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

6. Stereotypes can be based on:

- race

- ethnicity

- gender

- all of the above

7. What is discrimination?

- Biased thoughts against an individual or group

- Biased actions against an individual or group

- Belief that a race different from yours is inferior

- Another word for stereotyping

8. Which of the following is the best explanation of racism as a social fact?

- It needs to be eradicated by laws.

- It is like a magic pill.

- It does not need the actions of individuals to continue.

- None of the above

7.3 Theories of Race and Ethnicity

9. As a White person in the United States, being reasonably sure that you will be dealing with authority figures of the same race as you is a result of:

- intersection theory

- conflict theory

- white privilege

- scapegoating theory

10. Speedy Gonzalez is an example of:

- intersection theory

- stereotyping

- interactionist view

- culture of prejudice

7.4 Intergroup Relationships

11. Which intergroup relation displays the least tolerance?

- Segregation

- Assimilation

- Genocide

- Expulsion

12. What doctrine justified legal segregation in the South?

- Jim Crow

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- De jure

- Separate but equal

13. What intergroup relationship is represented by the “salad bowl” metaphor?

- Assimilation

- Pluralism

- Amalgamation

- Segregation

14. Amalgamation is represented by the _____________ metaphor.

- melting pot

- Statue of Liberty

- salad bowl

- separate but equal

7.5 Race and Ethnicity in the United States

15. What makes Native Americans unique as a subordinate group in the United States?

- They are the only group that experienced expulsion.

- They are the only group that was segregated.

- They are the only group that was enslaved.

- They are the only group that is indigenous to the United States.

16. Which subordinate group is often referred to as the “model minority?”

- African Americans

- Asian Americans

- White ethnic Americans

- Native Americans

17. Which federal act or program was designed to allow more Hispanic American immigration, not block it?

- The Bracero Program