In 2009, the eighteen-year-old South African athlete, Caster Semenya, won the women’s 800-meter world championship in Track and Field. Her time of 1:55:45, a surprising improvement from her 2008 time of 2:08:00, caused officials from the International Association of Athletics Foundation (IAAF) to question whether her win was legitimate. If this questioning were based on suspicion of steroid use, the case would be no different from that of Roger Clemens or Mark McGuire, or even Track and Field Olympic gold medal winner Marion Jones. But the questioning and eventual testing were based on allegations that Caster Semenya, no matter what gender identity she possessed, was biologically a male.

You may be thinking that distinguishing biological maleness from biological femaleness is surely a simple matter—just conduct some DNA or hormonal testing, throw in a physical examination, and you’ll have the answer. But it is not that simple. Both biologically male and biologically female people produce a certain amount of testosterone, and different laboratories have different testing methods, which makes it difficult to set a specific threshold for the number of male hormones produced by a female that renders her sex male. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) criteria for determining eligibility for sex-specific events are not intended to determine biological sex. “Instead these regulations are designed to identify circumstances in which a particular athlete will not be eligible (by reason of hormonal characteristics) to participate in the 2012 Olympic Games” in the female category (International Olympic Committee 2012).

To provide further context, during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, eight female athletes with XY chromosomes underwent testing and were ultimately confirmed as eligible to compete as women (Maugh 2009). To date, no males have undergone this sort of testing. Doesn’t that imply that when women perform better than expected, they are “too masculine,” but when men perform well they are simply superior athletes? Can you imagine Usain Bolt, the world’s fastest man, being examined by doctors to prove he was biologically male based solely on his appearance and athletic ability?

Can you explain how sex, sexuality, and gender are different from each other?

In this chapter, we will discuss the differences between sex and gender, along with issues like gender identity and sexuality. We will also explore various theoretical perspectives on the subjects of gender and sexuality, including the social construction of sexuality and queer theory.

16.1 Sex and Gender

Learning Objectives

- Define and differentiate between sex and gender

- Define and discuss what is meant by gender identity

- Understand and discuss the role of homophobia and heterosexism in society

- Distinguish the meanings of transgender, transsexual, and homosexual identities

When filling out a document such as a job application or school registration form you are often asked to provide your name, address, phone number, birth date, and sex or gender. But have you ever been asked to provide your sex and your gender? Like most people, you may not have realized that sex and gender are not the same. However, sociologists and most other social scientists view them as conceptually distinct. Sex refers to physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity. Gender refers to behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male.

A person’s sex, as determined by his or her biology, does not always correspond with the person’s gender. Therefore, the terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. A baby boy who is born with male genitalia will be identified as male. As he grows, however, he may identify with the feminine aspects of his culture. Since the term sex refers to biological or physical distinctions, characteristics of sex will not vary significantly between different human societies. Generally, persons of the female sex, regardless of culture, will eventually menstruate and develop breasts that can lactate. Characteristics of gender, on the other hand, may vary greatly between different societies. For example, in U.S. culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) are considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture.

The dichotomous view of gender (the notion that someone is either male or female) is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures, gender is viewed as fluid. In the past, some anthropologists used the term berdache to refer to individuals who occasionally or permanently dressed and lived as a different gender. The practice has been noted among certain Native American tribes (Jacobs, Thomas, and Lang 1997). Samoan culture accepts what Samoans refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. Individuals from other cultures may mislabel them as homosexuals because fa’afafines have a varied sexual life that may include men and women (Poasa 1992).

Social Policy and Debate

The Legalese of Sex and Gender

The terms sex and gender have not always been differentiated in the English language. It was not until the 1950s that U.S. and British psychologists and other professionals working with intersex and transsexual patients formally began distinguishing between sex and gender. Since then, psychological and physiological professionals have increasingly used the term gender (Moi 2005). By the end of the twenty-first century, expanding the proper usage of the term gender to everyday language became more challenging—particularly where legal language is concerned. In an effort to clarify usage of the terms sex and gender, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a 1994 briefing, “The word gender has acquired the new and useful connotation of cultural or attitudinal characteristics (as opposed to physical characteristics) distinctive to the sexes. That is to say, gender is to sex as feminine is to female and masculine is to male” (J.E.B. v. Alabama, 144 S. Ct. 1436 [1994]). Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a different take, however. Viewing the words as synonymous, she freely swapped them in her briefings so as to avoid having the word “sex” pop up too often. It is thought that her secretary supported this practice by suggestions to Ginsberg that “those nine men” (the other Supreme Court justices), “hear that word and their first association is not the way you want them to be thinking” (Case 1995). This anecdote reveals that both sex and gender are actually socially defined variables whose definitions change over time.

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is their physical, mental, emotional, and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male and/or female). Sexual orientation is typically divided into several categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the other sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the same sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; asexuality, a lack of sexual attraction or desire for sexual contact; pansexuality, an attraction to people regardless of sex, gender, gender identity, or gender expression; and queer, an umbrella term used to describe sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. Heterosexuals and homosexuals are referred to as “straight” and “gay,” respectively, but more inclusive terminology is needed. Proper terminology includes the acronyms LGBT and LGBTQ, which stands for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender” (and “Queer” or “Questioning” when the Q is added). The United States is a heteronormative society, meaning many people assume heterosexual orientation is biologically determined and unambiguous. Consider that LGBTQ people are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle 2011).

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation and may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to announce their sexual orientations, while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against U.S. society’s historical norms (APA 2008).

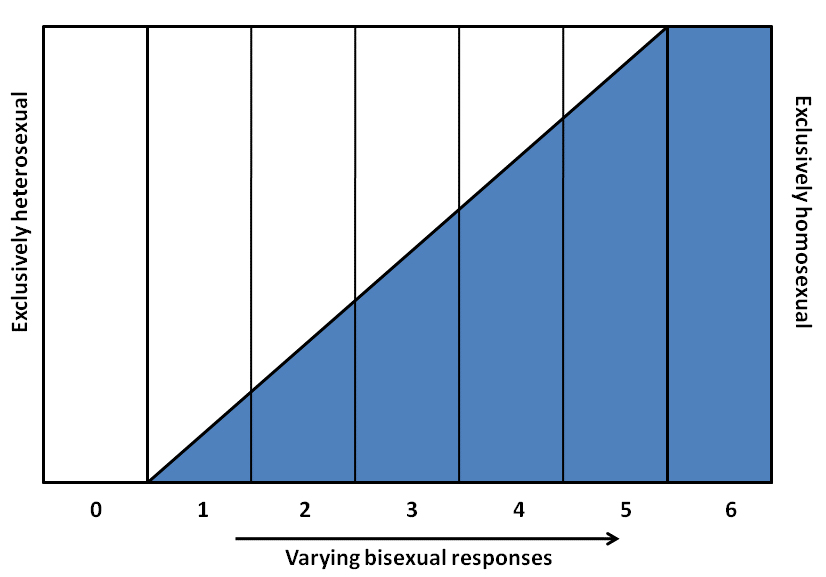

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. He created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. See the figure below. In his 1948 work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey 1948).

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual,” describing nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that in U.S. culture, males are subject to a clear divide between the two sides of this continuum, whereas females enjoy more fluidity. This can be illustrated by the way women in the United States can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, handholding, and physical closeness. In contrast, U.S. males refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative expectation that male sexual attraction should be exclusively for females. Research suggests that it is easier for women to violate these norms than men, because men are subject to more social disapproval for being physically close to other men (Sedgwick 1985).

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual orientation. Research has been conducted to study the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (APA 2008). Research, however, does present evidence showing that LGBTQ people are treated differently than heterosexuals in schools, the workplace, and the military. In 2011, for example, Sears and Mallory used General Social Survey data from 2008 to show that 27 percent of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) respondents reported experiencing sexual orientation-based discrimination during the five years prior to the survey. Further, 38 percent of openly LGB people experienced discrimination during the same time. (Note that this study did not specifically address other sexual orientations.)

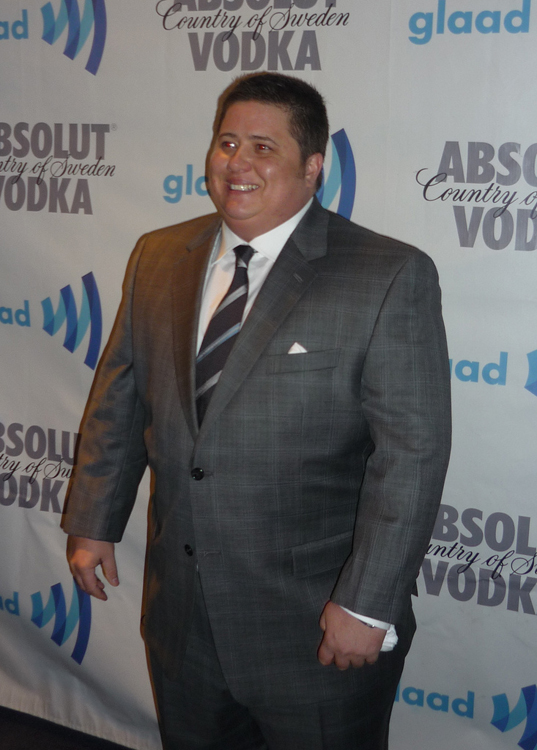

Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Some is based on heterosexism, which Herek (1990) suggests is both an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privilege heterosexuals and heterosexuality over other sexual orientations. Much like racism and sexism, heterosexism is a systematic disadvantage embedded in our social institutions, offering power to those who conform to heterosexual orientation while simultaneously disadvantaging those who do not. Homophobia, an extreme or irrational aversion to homosexuals, accounts for further stereotyping and discrimination. Transphobia is a fear, hatred or dislike of transgender people, and/or prejudice and discrimination against them by individuals or institutions. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have not come into effect until the last few years. In 2011, President Obama overturned “don’t ask, don’t tell,” a controversial policy that required gay and lesbian people in the US military to keep their sexuality undisclosed. The landmark 2020 Supreme Court decision added sexual orientation and gender identity as categories protected from employment discrimination by the Civil Rights Act. Organizations such as GLAAD (Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) advocate for LGBTQ rights and encourage governments and citizens to recognize the presence of sexual discrimination and work to prevent it.

Sociologically, it is clear that gay and lesbian couples are negatively affected when they are denied the legal right to marriage. In 1996, The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was passed, explicitly limiting the definition of “marriage” to a union between one man and one woman. It also allowed individual states to choose whether or not they recognized same-sex marriages performed in other states. In another blow to same-sex marriage advocates, in November 2008 California passed Proposition 8, a state law that limited marriage to unions of opposite-sex partners.

Over time, advocates for same-sex marriage won several court cases, laying the groundwork for legalized same-sex marriage across the United States, including the June 2013 decision to overturn part of DOMA in Windsor v. United States, and the Supreme Court’s dismissal of Hollingsworth v. Perry, affirming the August 2010 ruling that found California’s Proposition 8 unconstitutional. In October 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear appeals to rulings against same-sex marriage bans, which effectively legalized same-sex marriage in Indiana, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin, Colorado, North Carolina, West Virginia, and Wyoming (Freedom to Marry, Inc. 2014). Then, in 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Obergefell vs. Hodges that the right to a civil marriage was guaranteed to same-sex couples. In 2022, 37 states have legalized same-sex marriages and 13 states have not legalized them (Same-Sex Marriage in the United States, 2022).

Gender Roles

As we grow, we learn how to behave from those around us. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. The term gender role refers to society’s concept of how men and women are expected to look and how they should behave. These roles are based on norms, or standards, created by society. In U.S. culture, masculine roles are usually associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles are usually associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. Role learning starts with socialization at birth. Even today, our society is quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these color-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb.

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, which are active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Daughters are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender normative behavior (Caldera, Huston, and O’Brien 1998).

The drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles continues later in life. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics. Women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare (even though the term “doctor” still conjures the image of a man), and social work. These occupational roles are examples of typical U.S. male and female behavior, derived from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to them demonstrates fulfillment of social expectations but not necessarily personal preference (Diamond 2002).

Gender Identity

U.S. society allows for some level of flexibility when it comes to acting out gender roles. To a certain extent, men can assume some feminine roles and women can assume some masculine roles without interfering with their gender identity. Gender identity is a person’s deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.

Individuals who identify with a gender that is different from their biological sex are called transgender. Transgender is not the same as homosexual, and many homosexual males view both their sex and gender as male. A transgender woman is a person who was assigned male at birth but who identifies and/or lives as a woman; a transgender man was assigned female at birth but lives as a man. While determining the size of the transgender population is difficult, it is estimated that two to five percent of the U.S. population is transgender (Transgender Law and Policy Institute 2007).

Some transgender individuals may undertake a process to change their outward, physical, or sexual characteristics in order for their physical being to better align with their gender identity. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM). Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies: many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as another gender. This is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to another gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to a gender different from their biological sex, are not necessarily transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and it is not necessarily an expression against one’s assigned gender (APA 2008).

There is no single, conclusive explanation for why people are transgender. Transgender expressions and experiences are so diverse that it is difficult to identify their origin. Some hypotheses suggest biological factors such as genetics or prenatal hormone levels as well as social and cultural factors such as childhood and adulthood experiences. Most experts believe that all of these factors contribute to a person’s gender identity (APA 2008).

After years of controversy over the treatment of sex and gender in the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (Drescher 2010), the most recent edition, DSM-5, responds to allegations that the term “Gender Identity Disorder” is stigmatizing by replacing it with “Gender Dysphoria.” Gender Identity Disorder as a diagnostic category stigmatized the patient by implying there was something “disordered” about them. Gender Dysphoria, on the other hand, removes some of that stigma by taking the word “disorder” out while maintaining a category that will protect patient access to care, including hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery. In the DSM-5, Gender Dysphoria is a condition of people whose gender at birth is contrary to the one they identify with. For a person to be diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria, there must be a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experienced gender and the gender others would assign him or her, and it must continue for at least six months. In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present and verbalized. This diagnosis is now a separate category from sexual dysfunction and paraphilia, another important part of removing the stigma from the diagnosis (APA 2013). In 2019, the World Health Organization reclassified “gender identity disorder” as “gender incongruence,” and categorized it under sexual health rather than a mental disorder.

Changing the clinical description may contribute to a larger acceptance of transgender people in society. Studies show that people who identify as transgender are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as nontransgender individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2010; Giovanniello 2013). Organizations such as the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs and Global Action for Trans Equality work to prevent, respond to, and end all types of violence against LGBTQ. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgender individuals, this violence will end.

Sociology in the Real World

What if you had to live as a sex you were not biologically born to? If you are a man, imagine that you were forced to wear frilly dresses, dainty shoes, and makeup to special occasions, and you were expected to enjoy romantic comedies and daytime talk shows. If you are a woman, imagine that you were forced to wear shapeless clothing, put only minimal effort into your personal appearance, not show emotion, and watch countless hours of sporting events and sports-related commentary. It would be pretty uncomfortable, right? Well, maybe not. Many people enjoy participating in activities, whether they are associated with their biological sex or not, and would not mind if some of the cultural expectations for men and women were loosened.

Now, imagine that when you look at your body in the mirror, you feel disconnected. You feel your genitals are shameful and dirty, and you feel as though you are trapped in someone else’s body with no chance of escape. As you get older, you hate the way your body is changing, and, therefore, you hate yourself. These elements of disconnect and shame are important to understand when discussing transgender individuals. Fortunately, sociological studies pave the way for a deeper and more empirically grounded understanding of the transgender experience.

Pronoun usage also plays a role in a person’s gender identity. Pronouns are used in place of proper nouns, such as a name, during daily conversation. In many languages, including English, pronouns are gendered. That is, pronouns are intended to identify the gender of the individual being referenced. English has traditionally been binary, providing only “he/him/his,” for male subjects and “she/her/hers,” for female subjects.

This binary system excludes those who identify as neither male nor female. The word “they,” which was used for hundreds of years as a singular pronoun, is more inclusive. As a result, in fact, Merriam-Webster selected this use of “they” as Word of the Year for 2019. “They” and other pronouns are now used to reference those who do not identify as male or female on the spectrum of gender identities.

Gender-inclusive language is an important step in recognizing and accepting those whose gender is neither man nor woman (e.g., gender nonconforming, gender neutral, gender fluid, genderqueer, or non-binary).

16.2 Gender

Learning Objectives

- Explain the influence of socialization on gender roles in the United States

- Understand the stratification of gender in major American institutions

- Describe gender from the view of each sociological perspective

Gender and Socialization

The phrase “boys will be boys” is often used to justify behavior such as pushing, shoving, or other forms of aggression from young boys. The phrase implies that such behavior is unchangeable and something that is part of a boy’s nature. Aggressive behavior, when it does not inflict significant harm, is often accepted from boys and men because it is congruent with the cultural script for masculinity. The “script” written by society is in some ways similar to a script written by a playwright. Just as a playwright expects actors to adhere to a prescribed script, society expects women and men to behave according to the expectations of their respective gender roles. Scripts are generally learned through a process known as socialization, which teaches people to behave according to social norms.

Socialization

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes. For example, society often views riding a motorcycle as a masculine activity and, therefore, considers it to be part of the male gender role. Attitudes such as this are typically based on stereotypes and oversimplified notions about members of a group. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. For example, women may be thought of as too timid or weak to ride a motorcycle.

Gender stereotypes form the basis of sexism. Sexism refers to prejudiced beliefs that value one sex over another. It varies in its level of severity. In parts of the world where women are strongly undervalued, young girls may not be given the same access to nutrition, healthcare, and education as boys. Further, they will grow up believing they deserve to be treated differently from boys (UNICEF 2011; Thorne 1993). While it is illegal in the United States when practiced as discrimination, unequal treatment of women continues to pervade social life. It should be noted that discrimination based on sex occurs at both the micro and macro levels. Many sociologists focus on discrimination that is built into the social structure; this type of discrimination is known as institutional discrimination (Pincus 2008).

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads men and women into a false sense that they are acting naturally rather than following a socially constructed role.

Family is the first agent of socialization. There is considerable evidence that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. Generally speaking, girls are given more latitude to step outside of their prescribed gender role (Coltrane and Adams 2004; Kimmel 2000; Raffaelli and Ontai 2004). However, differential socialization typically results in greater privileges afforded to sons. For instance, boys are allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age than daughters. They may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfew. Sons are also often free from performing domestic duties such as cleaning or cooking and other household tasks that are considered feminine. Daughters are limited by their expectation to be passive and nurturing, be generally obedient, and assume many of the domestic responsibilities.

Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be asked to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel 2000). This is true in many types of activities, including a preference for toys, play styles, discipline, chores, and personal achievements. As a result, boys tend to be particularly attuned to their father’s disapproval when engaging in an activity that might be considered feminine, like dancing or singing (Coltraine and Adams 2008). Parental socialization and normative expectations also vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. Black families, for instance, are more likely than White families to model an egalitarian role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson 2004).

The reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes continues once a child reaches school age. Until very recently, schools were rather explicit in their efforts to stratify boys and girls. The first step toward stratification was segregation. Girls were encouraged to take home economics or humanities courses and boys to take math and science.

Studies suggest that gender socialization still occurs in schools today, perhaps in less obvious forms (Lips 2004). Teachers may not even realize they are acting in ways that reproduce gender-differentiated behavior patterns. Yet any time they ask students to arrange their seats or line up according to gender, teachers may be asserting that boys and girls should be treated differently (Thorne 1993).

Even in levels as low as kindergarten, schools subtly convey messages to girls indicating that they are less intelligent or less important than boys. For example, in a study of teacher responses to male and female students, data indicated that teachers praised male students far more than female students. Teachers interrupted girls more often and gave boys more opportunities to expand on their ideas (Sadker and Sadker 1994). Further, in social as well as academic situations, teachers have traditionally treated boys and girls in opposite ways, reinforcing a sense of competition rather than collaboration (Thorne 1993). Boys are also permitted a greater degree of freedom to break rules or commit minor acts of deviance, whereas girls are expected to follow rules carefully and adopt an obedient role (Ready 2001).

Mimicking the actions of significant others is the first step in the development of a separate sense of self (Mead 1934). Like adults, children become agents who actively facilitate and apply normative gender expectations to those around them. When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may face negative sanctions such as being criticized or marginalized by their peers. Though many of these sanctions are informal, they can be quite severe. For example, a girl who wishes to take karate class instead of dance lessons may be called a “tomboy” and face difficulty gaining acceptance from both male and female peer groups (Ready 2001). Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender nonconformity (Coltrane and Adams 2004; Kimmel 2000).

Mass media serves as another significant agent of gender socialization. In television and movies, women tend to have less significant roles and are often portrayed as wives or mothers. When women are given a lead role, it often falls into one of two extremes: a wholesome, saint-like figure or a malevolent, hypersexual figure (Etaugh and Bridges 2003). This same inequality is pervasive in children’s movies (Smith 2008). Research indicates that in the ten top-grossing G-rated movies released between 1991 and 2013, nine out of ten characters were male (Smith 2008).

Television commercials and other forms of advertising also reinforce inequality and gender-based stereotypes. Women are almost exclusively present in ads promoting cooking, cleaning, or childcare-related products (Davis 1993). Think about the last time you saw a man star in a dishwasher or laundry detergent commercial. In general, women are underrepresented in roles that involve leadership, intelligence, or a balanced psyche. Of particular concern is the depiction of women in ways that are dehumanizing, especially in music videos. Even in mainstream advertising, however, themes intermingling violence and sexuality are quite common (Kilbourne 2000).

Social Stratification and Inequality

Stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. The United States is characterized by gender stratification (as well as stratification of race, income, occupation, and the like). Evidence of gender stratification is especially keen within the economic realm. According to the April 2022 data released by the Department of Labor, women make up 56.7% of the labor workforce and men make up 68% of the labor workforce. Despite these recent statistics, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs. Tom Spiggle with Forbes Magazine wrote that women earn 82 cents for every dollar a man earns and this payroll gap is not expected to end, at this current rate, until 2059 (2021). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double-duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989).

Gender stratification through the division of labor is not exclusive to the United States. According to George Murdock’s classic work, Outline of World Cultures (1954), all societies classify work by gender. When a pattern appears in all societies, it is called a cultural universal. While the phenomenon of assigning work by gender is universal, its specifics are not. The same task is not assigned to either men or women worldwide. But the way each task’s associated gender is valued is notable. In Murdock’s examination of the division of labor among 324 societies around the world, he found that in nearly all cases the jobs assigned to men were given greater prestige (Murdock and White 1968). Even if the job types were very similar and the differences slight, men’s work was still considered more vital.

There is a long history of gender stratification in the United States. When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality (see timeline below), but underlying effects of male dominance still permeate many aspects of society.

- Before 1809—Women could not execute a will

- Before 1840—Women were not allowed to own or control property

- Before 1920—Women were not permitted to vote

- Before 1963—Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

- Before 1973—Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion (Imbornoni 2009)

Theoretical Perspectives on Gender

Sociological theories help sociologists to develop questions and interpret data. For example, a sociologist studying why middle-school girls are more likely than their male counterparts to fall behind grade-level expectations in math and science might use a feminist perspective to frame her research. Another scholar might proceed from the conflict perspective to investigate why women are underrepresented in political office, and an interactionist might examine how the symbols of femininity interact with symbols of political authority to affect how women in Congress are treated by their male counterparts in meetings.

Structural Functionalism

Structural functionalism has provided one of the most important perspectives of sociological research in the twentieth century and has been a major influence on research in the social sciences, including gender studies. Viewing the family as the most integral component of society, assumptions about gender roles within marriage assume a prominent place in this perspective.

Functionalists argue that gender roles were established well before the pre-industrial era when men typically took care of responsibilities outside of the home, such as hunting, and women typically took care of the domestic responsibilities in or around the home. These roles were considered functional because women were often limited by the physical restraints of pregnancy and nursing and were unable to leave the home for long periods of time. Once established, these roles were passed on to subsequent generations, since they served as an effective means of keeping the family system functioning properly.

When changes occurred in the social and economic climate of the United States during World War II, changes in the family structure also occurred. Many women had to assume the role of breadwinner (or modern hunter-gatherer) alongside their domestic role in order to stabilize a rapidly changing society. When the men returned from war and wanted to reclaim their jobs, society fell back into a state of imbalance, as many women did not want to forfeit their wage-earning positions (Hawke 2007).

Conflict Theory

According to conflict theory, society is a struggle for dominance among social groups (like women versus men) that compete for scarce resources. When sociologists examine gender from this perspective, we can view men as the dominant group and women as the subordinate group. According to conflict theory, social problems are created when dominant groups exploit or oppress subordinate groups. Consider the Women’s Suffrage Movement or the debate over women’s “right to choose” their reproductive futures. It is difficult for women to rise above men, as dominant group members create the rules for success and opportunity in society (Farrington and Chertok 1993).

Friedrich Engels, a German sociologist, studied family structure and gender roles. Engels suggested that the same owner-worker relationship seen in the labor force is also seen in the household, with women assuming the role of the proletariat. This is due to women’s dependence on men for the attainment of wages, which is even worse for women who are entirely dependent upon their spouses for economic support. Contemporary conflict theorists suggest that when women become wage earners, they can gain power in the family structure and create more democratic arrangements in the home, although they may still carry the majority of the domestic burden, as noted earlier (Rismanand and Johnson-Sumerford 1998).

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is a type of conflict theory that examines inequalities in gender-related issues. It uses the conflict approach to examine the maintenance of gender roles and inequalities. Radical feminism, in particular, considers the role of the family in perpetuating male dominance. In patriarchal societies, men’s contributions are seen as more valuable than those of women. Patriarchal perspectives and arrangements are widespread and taken for granted. As a result, women’s viewpoints tend to be silenced or marginalized to the point of being discredited or considered invalid.

Sanday’s study of the Indonesian Minangkabau (2004) revealed that in societies some consider to be matriarchies (where women comprise the dominant group), women and men tend to work cooperatively rather than competitively regardless of whether a job is considered feminine by U.S. standards. The men, however, do not experience the sense of bifurcated consciousness under this social structure that modern U.S. females encounter (Sanday 2004).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism aims to understand human behavior by analyzing the critical role of symbols in human interaction. This is certainly relevant to the discussion of masculinity and femininity. Imagine that you walk into a bank hoping to get a small loan for school, a home, or a small business venture. If you meet with a male loan officer, you may state your case logically by listing all the hard numbers that make you a qualified applicant as a means of appealing to the analytical characteristics associated with masculinity. If you meet with a female loan officer, you may make an emotional appeal by stating your good intentions as a means of appealing to the caring characteristics associated with femininity.

Because the meanings attached to symbols are socially created and not natural, fluid and not static, we act and react to symbols based on the current assigned meaning. The word gay, for example, once meant “cheerful,” but by the 1960s it carried the primary meaning of “homosexual.” In transition, it was even known to mean “careless” or “bright and showing” (Oxford American Dictionary 2010). Furthermore, the word gay (as it refers to a homosexual), carried a somewhat negative and unfavorable meaning fifty years ago, but it has since gained more neutral and even positive connotations. When people perform tasks or possess characteristics based on the gender role assigned to them, they are said to be doing gender. This notion is based on the work of West and Zimmerman (1987). Whether we are expressing our masculinity or femininity, West and Zimmerman argue, we are always “doing gender.” Thus, gender is something we do or perform, not something we are.

In other words, both gender and sexuality are socially constructed. The social construction of sexuality refers to the way in which socially created definitions about the cultural appropriateness of sex-linked behavior shape the way people see and experience sexuality. This is in marked contrast to theories of sex, gender, and sexuality that link male and female behavior to biological determinism, or the belief that men and women behave differently due to differences in their biology.

Sociological Reasearch

Being Male, Being Female, and Being Healthy

In 1971, Broverman and Broverman conducted a groundbreaking study on the traits mental health workers ascribed to males and females. When asked to name the characteristics of a female, the list featured words such as unaggressive, gentle, emotional, tactful, less logical, not ambitious, dependent, passive, and neat. The list of male characteristics featured words such as aggressive, rough, unemotional, blunt, logical, direct, active, and sloppy (Seem and Clark 2006). Later, when asked to describe the characteristics of a healthy person (not gender-specific), the list was nearly identical to that of a male.

This study uncovered the general assumption that being female is associated with being somewhat unhealthy or not of sound mind. This concept seems extremely dated, but in 2006, Seem and Clark replicated the study and found similar results. Again, the characteristics associated with a healthy male were very similar to that of a healthy (genderless) adult. The list of characteristics associated with being female broadened somewhat but did not show significant change from the original study (Seem and Clark 2006). This interpretation of feminine characteristics may help us one day better understand gender disparities in certain illnesses, such as why one in eight women can be expected to develop clinical depression in her lifetime (National Institute of Mental Health 1999). Perhaps these diagnoses are not just a reflection of women’s health but also a reflection of society’s labeling of female characteristics or the result of institutionalized sexism.