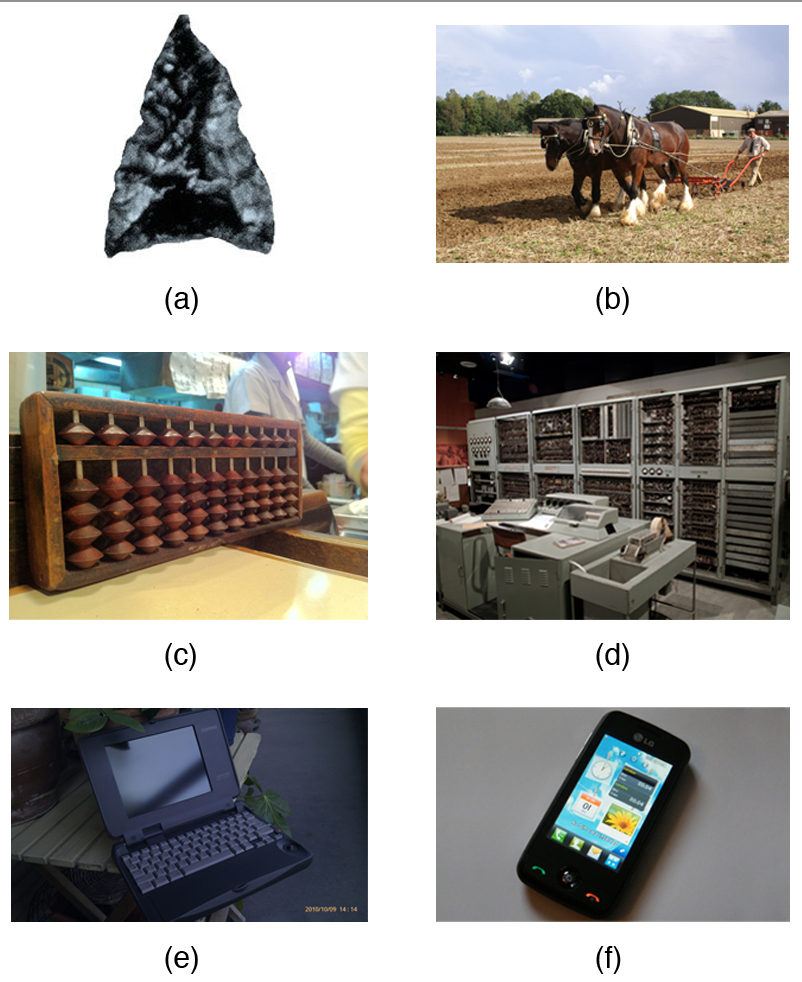

15.1 Technology Today

Abbott, Tyler. 2020. “America’s Love Affair With Their Phones.” Reviews.org. (https://www.reviews.org/mobile/cell-phone-addiction/#Smart_Phone_Addiction_Stats)

Allchin, Josie. 2012. “New guidance for brands using child ambassadors.” Marketing Week. (https://www.marketingweek.com/new-guidance-for-brands-using-child-ambassadors/)

American Press Institute. 2015. “Race and ethnicity, device usage, and connectivity.” (https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/race-ethnicity-device-usage-connectivity/)

Auxier, Brooke and Rainie, Lee. 2019. “Americans and Privacy.” Pew Research Center. (https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/)

Guillén, M.F., and S.L. Suárez. 2005. “Explaining the Global Digital Divide: Economic, Political and Sociological Drivers of Cross-National Internet Use.” Social Forces 84:681–708.

Hall, J. A., & Baym, N. K. (2012). “Calling and texting (too much): Mobile maintenance expectations, (over) dependence, entrapment, and friendship satisfaction.” New Media and Society, 14, 316–331.

Kooser, Amanda. 2015. “Sleep with your smartphone in hand? You’re not alone.” CNET. (https://www.cnet.com/news/americans-like-to-snooze-with-their-smartphones-says-survey/)

Levy, Sara. 2019. “No, I Won’t Post A Picture of My Kid on Social Media.” Glamour. (https://www.glamour.com/story/mom-wont-post-childs-photo-on-social-media)

Luo, Shanhong. 2014. “Effects of Texting on Satisfaction in Romantic Relationships: The Role of Attachment.” Computers in Human Behavior. April 2014. (10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.014)

Lewis, Dave. 2014. “ICloud Data Breach: Hacking and Celebrity Photos.” Forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved October 6, 2014 (https://www.forbes.com/sites/davelewis/2014/09/02/icloud-data-breach-hacking-and-nude-celebrity-photos/?sh=735a2af22de7).

Liff, Sondra, and Adrian Shepherd. 2004. “An Evolving Gender Digital Divide.” Oxford Internet Institute, Internet Issue Brief No. 2. Retrieved January 11, 2012 (https://educ.ubc.ca/faculty/bryson/565/genderdigdiv.pdf).

Martin, Michael J. R. 2019. “Rural and Lower Income Counties Lag Nation in Internet Subscription.” (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/12/rural-and-lower-income-counties-lag-nation-internet-subscription.html)

McChesney, Robert. 1999. Rich Media, Poor Democracy: Communication Politics in Dubious Times. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Moreno, Johan. 2020. “YouTube Disables Personalized Ads, Comments on Children’s Videos.” Forbes. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/johanmoreno/2020/01/06/youtube-disables-personalized-ads-comments-on-childrens-videos/?sh=202ef7695bf0)

Mossberger, Karen, Caroline Tolbert, and Michele Gilbert. 2006. “Race, Place, and Information Technology.” Urban Affairs Review 41:583–620.

Perrin, Andrew and Turner, Erica. 2019. “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites.” Pew Research Center. (https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/20/smartphones-help-blacks-hispanics-bridge-some-but-not-all-digital-gaps-with-whites/)

“Planned Obsolescence.” 2009. The Economist, March 23. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.economist.com/node/13354332).

Population Reference Bureau. 2020. “Children, Coronavirus, and the Digital Divide: Native American, Black, and Hispanic Students at Greater Educational Risk During Pandemic” (https://www.prb.org/coronavirus-digital-divide-education/).

Rainie, Lee, Sara Kiesler, Ruogo Kang, and Mary Madden. 2013. “Anonymity, Privacy, and Security Online.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 5, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/05/anonymity-privacy-and-security-online/).

Rappaport, Richard. 2009. “A Short History of the Digital Divide.” Edutopia, October 27. Retrieved January 10, 2012 (http://www.edutopia.org/digital-generation-divide-connectivity).

Sciadas, George. 2003. “Monitoring the Digital Divide … and Beyond.” World Bank Group. Retrieved January 22, 2012 (http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.20.html).

Smith, Aaron. 2012. “The Best (and Worst) of Mobile Connectivity.” Pew Research Internet Project. Retrieved December 19, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/11/30/the-best-and-worst-of-mobile-connectivity/).

Time.com. 2014. “Rankings.” Fortune. Time.com. Retrieved October 1, 2014 (http://fortune.com/rankings/).

Washington, Jesse. 2011. “For Minorities, New ‘Digital Divide’ Seen.” Pew Internet and American Life Project, January 10. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.pewinternet.org/Media-Mentions/2011/For-minorities-new-digital-divide-seen.aspx).

15.2 Media and Technology in Society

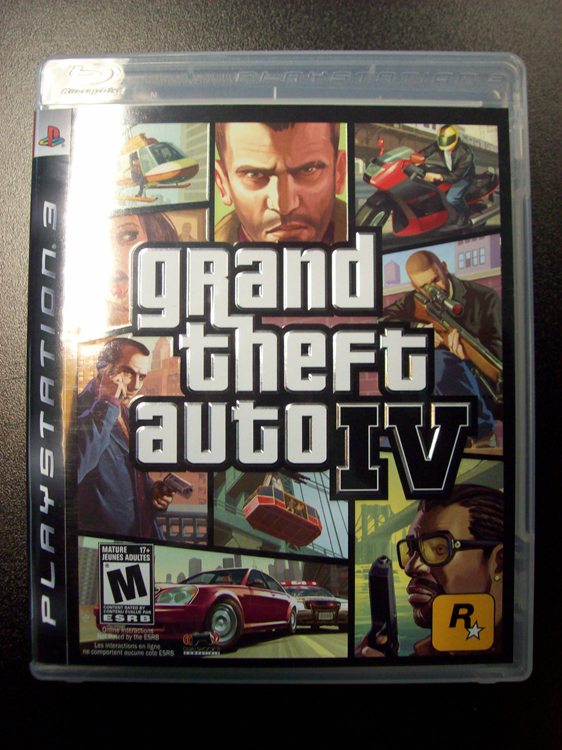

Anderson, C.A., and B.J. Bushman. 2001. “Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggressive Behavior, Aggressive Cognition, Aggressive Affect, Physiological Arousal, and Prosocial Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Scientific Literature.” Psychological Science 12:353–359.

Anderson, Craig. 2003. “Violent Video Games: Myths, Facts and Unanswered Questions.” American Psychological Association, October. Retrieved January 13, 2012 (http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2003/10/anderson.aspx).

Anderson, Philip, and Michael Tushman. 1990. “Technological Discontinuities and Dominant Designs: A Cyclical Model of Technological Change.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35:604–633.

Dillon, Andrew. 1992. “Reading From Paper Versus Screens: A Critical Review of the Empirical Literature.” Ergonomics 35(10): 1297–1326.

Deng T, Kanthawala S, Meng J, et al. Measuring smartphone usage and task switching with log tracking and self-reports. Mobile Media & Communication. 2019;7(1):3-23. doi:10.1177/2050157918761491

DeSilver, Drew. 2014. “Overall Book Readership Stable, But e-Books Becoming More Popular.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 5, 2014 (http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/21/overall-book-readership-stable-but-e-books-becoming-more-popular/).

Duggan, Maeve, and Aaron Smith. “Social Media Update 2013.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 2, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/12/30/social-media-update-2013/).

Federal Communications Commission 2022. FCC Commits another $86M in Emergency Connectivity Funding February 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022. (https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-commits-another-86m-emergency-connectivity-funding).

International Telecommunication Unions. 2014. “The World in 2014: ICT Facts and Figures.” United Nations. Retrieved December 5, 2014 (http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2014-e.pdf).

Jansen, Jim. “Use of the Internet in Higher-income Households.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 1, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/11/24/use-of-the-internet-in-higher-income-households).

Kumar, Ravi. 2014. “Social Media and Social Change: How Young People Are Tapping into Technology.” Youthink! N.p. Retrieved October 3, 2014 (http://blogs.worldbank.org/youthink/social-media-and-social-change-how-young-people-are-tapping-technology).

Lievrouw, Leah A., and Sonia Livingstone, eds. 2006. Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences. London: SAGE Publications.

McManus, John. 1995. “A Market-Based Model of News Production.” Communication Theory 5:301–338.

Mangen, A., B.R. Walgermo, and K. Bronnick. 2013. “Reading Linear Texts on Paper Versus Computer Screen: Effects on Reading Comprehension.” International Journal of Educational Research 58:61–68.

Nielsen. 2013. “‘Bingeing’ in the New Viewing for Over-the-Top-Streamers.” Retrieved December 5, 2014 (http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2013/binging-is-the-new-viewing-for-over-the-top-streamers.html).

Noyes, Jan, and Kate J. Garland. 2008. “Computer- Vs. Paper-Based Tasks: Are They Equivalent?” Ergonomics 51(9): 1352–1375.

Pew Research Center. 2010. “State of the News Media 2010.” Pew Research Center Publications, March 15. Retrieved January 24, 2012 (http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1523/state-of-the-news-media-2010).

Pew Research Center (2021). Social Media Fact Sheet April 78, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022 (https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/).

Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism. 2013. “The State of the News Media 2013.” Pew Research Center Publications. Retrieved December 5, 2014 (http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2013/overview-5/key-findings/).

Prior, Markus. 2005. “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49(3):577–592.

ProCon. 2012. “Video Games.” January 5. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://videogames.procon.org/).

Reuters. 2013. “YouTube Stats: Site Has 1 Billion Active Users Each Month.” Huffington Post. Retrieved December 5, 2014 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/21/youtube-stats_n_2922543.html).

Singer, Natasha. 2011. “On Campus, It’s One Big Commercial.” New York Times, September 10. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/11/business/at-colleges-the-marketers-are-everywhere.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&ref=education).

Smith, Aaron. 2012. “The Best (and Worst) of Mobile Connectivity.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 3, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/11/30/the-best-and-worst-of-mobile-connectivity/).

Smith, Aaron. 2014a. “African Americans and Technology Use.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 1, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/01/06/african-americans-and-technology-use/).

Smith, Aaron. 2014b. “Older Adults and Technology Use.” Pew Research Centers Internet American Life Project RSS. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 2, 2014 (http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/).

United States Patent and Trademark Office. 2012. “General Information Concerning Patents.” Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.uspto.gov/patents/resources/general_info_concerning_patents.jsphttp://www.uspto.gov/patents/resources/general_info_concerning_patents.jsp).

van de Donk, W., B.D. Loader, P.G. Nixon, and D. Rucht, eds. 2004. Cyberprotest: New Media, Citizens, and Social Movements. New York: Routledge.

World Association of Newspapers. 2004. “Newspapers: A Brief History.” Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.wan-press.org/article.php3?id_article=2821).

15.3 Global Implications of Media and Technology

Acker, Jenny C., and Isaac M. Mbiti. 2010. “Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(3):207–232. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.24.3.207).

Bagdikian, Ben H. 2004. The New Media Monopoly. Boston, MA: Beacon Press Books.

Bristow, Michael. 2011. “Can China Control Social Media Revolution?” BBC News China, November 2. Retrieved January 14, 2012 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-15383756).

Compaine, B. 2005. “Global Media.” Pp. 97-101 in Living in the Information Age: A New Media Reader Belmont: Wadsworth Thomson Learning.

Friedman, Thomas. 2005. The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

ITU News. 2009. “ITU Telecom World 2009: Special Report: Reflecting New Needs and Realities.” November. Retrieved January 14, 2012 (http://www.itu.int/net/itunews/issues/2009/09/26.aspx).

Jan, Mirza. 2009. “Globalization of Media: Key Issues and Dimensions.” European Journal of Scientific Research 29:66–75.

Katine Chronicles Blog. 2010. “Are Mobile Phones Africa’s Silver Bullet?” The Guardian, January 14. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.guardian.co.uk/katine/katine-chronicles-blog?page=6).

Ma, Damien. 2011. “2011: When Chinese Social Media Found Its Legs.” The Atlantic, December 18. Retrieved January 15, 2012 (http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/12/2011-when-chinese-social-media-found-its-legs/250083/).

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pierson, David. 2012. “Number of Web Users in China Hits 513 Million.” Los Angeles Times, January 16. Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/technology/2012/01/chinese-web-users-grow-to-513-million.html).

The World Bank. 2008. “Global Economic Prospects 2008: Technology Diffusion in the Developing World.” World Bank. Retrieved January 24, 2012 (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGEP2008/Resources/GEP_ove_001-016.pdf).

15.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

Brasted, Monica. 2010. “Care Bears vs. Transformers: Gender Stereotypes in Advertisements.” Retrieved January 10, 2012 (http://www.sociology.org/media-studies/care-bears-vs-transformers-gender-stereotypes-in-advertisements).

Carmi, Evan, Matthew Ericson, David Nolen, Kevin Quealy, Michael Strickland, Jeremy White, and Derek Willis. 2012. “The 2012 Money Race: Compare the Candidates.” New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2012 (http://elections.nytimes.com/2012/campaign-finance).

Foucault, Michel. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Fox, Jesse, and Jeremy Bailenson. 2009. “Virtual Virgins and Vamps: The Effects of Exposure to Female Characters’ Sexualized Appearance and Gaze in an Immersive Virtual Environment.” Sex Roles 61:147–157.

Gamson, William, David Croteau, William Hoynes, and Theodore Sasson. 1992. “Media Images and the Social Construction of Reality.” Annual Review of Sociology 18:373–393.

Gentile, Douglas, Lindsay Mathieson, and Nikki Crick. 2011. “Media Violence Associations with the Form and Function of Aggression among Elementary School Children.” Social Development 20:213–232.

Kautiainen, S., L. Koivusilta, T. Lintonen, S. M. Virtanen, and A. Rimpelä. 2005. “Use of Information and Communication Technology and Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Adolescents.” International Journal of Obesity 29:925–933

Krahe, Barbara, Ingrid Moller, L. Huesmann, Lucyna Kirwil, Julianec Felber, and Anja Berger. 2011. “Desensitization to Media Violence: Links With Habitual Media Violence Exposure, Aggressive Cognitions, and Aggressive Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100:630–646.

Lazerfeld, Paul F. and Robert K. Merton. 1948. “Mass Communication, Popular Taste, and Organized Social Action.” The Communication of Ideas. New York: Harper & Bros.

Magnet, Shoshana. 2007. “Feminist Sexualities, Race, and The Internet: An Investigation of suicidegirls.com.” New Media & Society 9:577-602.

Mills, C. Wright. 2000 [1956]. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

NielsenWire. 2011. “Nielsen Estimates Number of U.S. Television Homes to be 114.7 Million.” May 3. Retrieved January 15, 2012 (http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/media_entertainment/nielsen-estimates-number-of-u-s-television-homes-to-be-114-7-million/).

Pierce, Tess. 2011. “Singing at the Digital Well: Blogs as Cyberfeminist Sites of Resistance.” Feminist Formations 23:196–209.

Savage, Joanne. 2003. “Does Viewing Violent Media Really Cause Criminal Violence? A Methodological Review.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 10:99–128.

Shoemaker, Pamela and Tim Vos. 2009. “Media Gatekeeping.” Pp. 75–89 in An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, 2nd ed., edited by D. Stacks and M. Salwen. New York: Routledge.

U.S. Department of Commerce. 2011. “Women in STEM: A Gender Gap to Innovation.” August. Retrieved February 22, 2012 (http://www.esa.doc.gov/sites/default/files/reports/documents/womeninstemagaptoinnovation8311.pdf/).

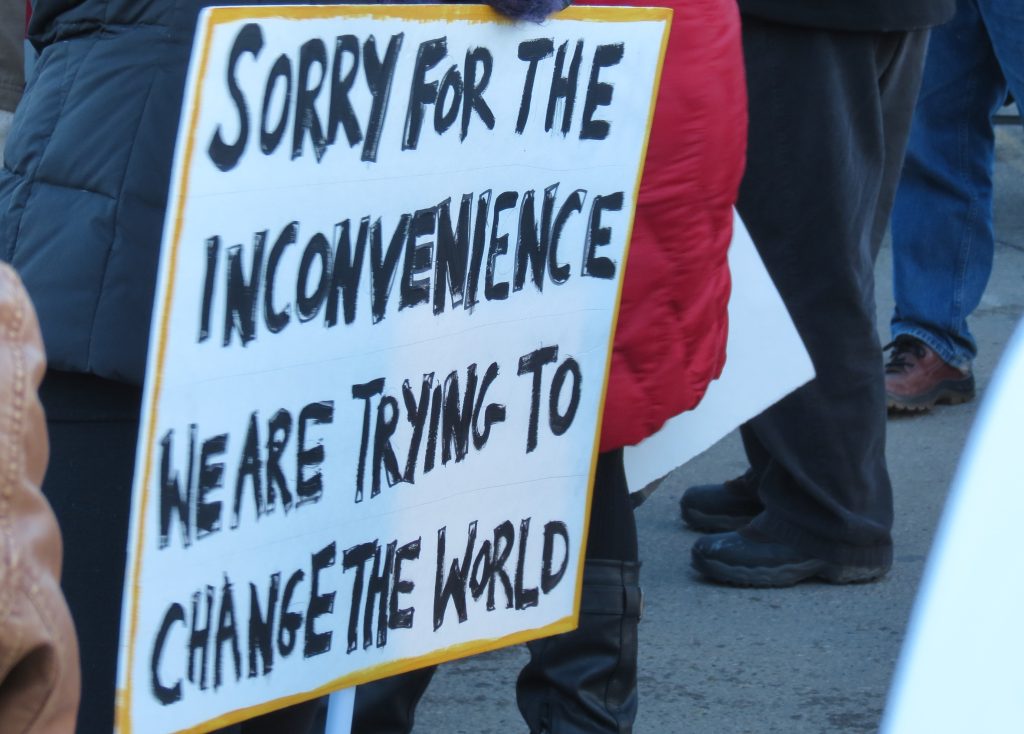

Social Movements and Social Change

AFL-CIO. 2014. “Executive Paywatch.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.aflcio.org/Corporate-Watch/Paywatch-2014).

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Davies, James C. 1962. “Toward a Theory of Revolution.” American Sociological Review 27, no. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.jstor.org/discover/2089714?sid=21104884442891&uid=3739256&uid=3739704&uid=4&uid=2).

Gell, Aaron. 2011. “The Wall Street Protesters: What the Hell Do They Want?” New York Observer. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://observer.com/2011/09/the-wall-street-protesters-what-the-hell-do-they-want/).

Le Tellier, Alexandria. 2012. “What Occupy Wall Street Wants.” Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://articles.latimes.com/2012/sep/17/news/la-ol-occupy-wall-street-anniversary-message-20120917).

NAACP. 2011. “100 Years of History.” Retrieved December 21, 2011 (http://www.naacp.org/pages/naacp-history).

15.5 Collective Behavior

Blumer, Herbert. 1969. “Collective Behavior.” Pp. 67–121 in Principles of Sociology, edited by A.M. Lee. New York: Barnes and Noble.

LeBon, Gustave. 1960 [1895]. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. New York: Viking Press.

Lofland, John. 1993. “Collective Behavior: The Elementary Forms.” Pp. 70–75 in Collective Behavior and Social Movements, edited by Russel Curtis and Benigno Aguirre. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

McPhail, Clark. 1991. The Myth of the Madding Crowd. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Smelser, Neil J. 1963. Theory of Collective Behavior. New York: Free Press.

Turner, Ralph, and Lewis M. Killian. 1993. Collective Behavior. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, N. J., Prentice Hall.

15.6 Social Movements

A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2014. “Civil Rights Movement.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-movement).

Aberle, David. 1966. The Peyote Religion among the Navaho. Chicago: Aldine.

AP/The Huffington Post. 2014. “Obama: DOMA Unconstitutional, DOJ Should Stop Defending in Court.” The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2014. (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/02/23/obama-doma-unconstitutional_n_827134.html).

Area Chicago. 2011. “About Area Chicago.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 (http://www.areachicago.org).

Benford, Robert, and David Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26:611–639.

Blumer, Herbert. 1969. “Collective Behavior.” Pp. 67–121 in Principles of Sociology, edited by A.M. Lee. New York: Barnes and Noble.

Buechler, Steven. 2000. Social Movement in Advanced Capitalism: The Political Economy and Social Construction of Social Activism. New York: Oxford University Press.

CNN U.S. 2014. “Same-Sex Marriage in the United States.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.cnn.com/interactive/us/map-same-sex-marriage/).

CBS Interactive Inc. 2014. “Anonymous’ Most Memorable Hacks.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/anonymous-most-memorable-hacks/9/).

Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 2011. “Letter from the Attorney General to Congress on Litigation Involving the Defense of Marriage Act.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/letter-attorney-general-congress-litigation-involving-defense-marriage-act).

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2010. “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted.” The New Yorker, October 4. Retrieved December 23, 2011 (http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell?currentPage=all).

Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Human Rights Campaign. 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2011 (http://www.hrc.org).

McAdam, Doug, and Ronnelle Paulsen. 1993. “Specifying the Relationship between Social Ties and Activism.” American Journal of Sociology 99:640–667.

McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82:1212–1241.

National Organization for Marriage. 2014. “About NOM.” Retrieved January 28, 2012 (http://www.nationformarriage.org).

Sauter, Theresa, and Gavin Kendall. 2011. “Parrhesia and Democracy: Truthtelling, WikiLeaks and the Arab Spring.” Social Alternatives 30, no.3: 10–14.

Schmitz, Paul. 2014. “How Change Happens: The Real Story of Mrs. Rosa Parks & the Montgomery Bus Boycott.” Huffington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/paul-schmitz/how-change-happens-the-re_b_6237544.html).

Slow Food. 2011. “Slow Food International: Good, Clean, and Fair Food.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 (http://www.slowfood.com).

Snow, David, E. Burke Rochford, Jr., Steven Worden, and Robert Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” American Sociological Review 51:464–481.

Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization.” International Social Movement Research 1:197–217.

Technopedia. 2014. “Anonymous.” Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.techopedia.com/definition/27213/anonymous-hacking).

Texas Secede! 2009. “Texas Secession Facts.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 (http://www.texassecede.com).

Tilly, Charles. 1978. From Mobilization to Revolution. New York: McGraw-Hill College.

Wagenseil, Paul. 2011. “Anonymous ‘hacktivists’ attack Egyptian websites.” NBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://www.nbcnews.com/id/41280813/ns/technology_and_science-security/t/anonymous-hacktivists-attack-egyptian-websites/#.VJHmuivF-Sq).

15.7 Social Change

350.org. 2014. “350.org.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://350.org/).

ABC News. 2007. “Parents: Cyber Bullying Led to Teen’s Suicide.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3882520).

CBS News. 2011. “Record Year for Billion Dollar Disasters.” CBS News, Dec 11. Retrieved December 26, 2011 (http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-201_162-57339130/record-year-for-billion-dollar-disasters).

Center for Biological Diversity. 2014. “The Extinction Crisis.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/biodiversity/elements_of_biodiversity/extinction_crisis/).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). n.d. “Technology and Youth: Protecting your Children from Electronic Aggression: Tip Sheet.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ea-tipsheet-a.pdf).

Freidman, Thomas. 2005. The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the 21st Century. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

Gao, Huiji, Geoffrey Barbier, and Rebecca Goolsby. 2011. “Harnessing the Crowdsourcing Power of Social Media for Disaster Relief.” IEEE Intelligent Systems. 26, no. 03: 10–14.

Irwin, Patrick. 1975. “An Operational Definition of Societal Modernization.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 23:595–613.

Klein, Naomi. 2008. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Picador.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2014. The Sixth Extinction. New York: Henry Holt and Co.

Megan Meier Foundation. 2014a. “Megan Meier Foundation.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://www.meganmeierfoundation.org/).

Megan Meier Foundation. 2014b. “Megan’s Story.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://www.meganmeierfoundation.org/megans-story.html).

Miller, Laura. 2010. “Fresh Hell: What’s Behind the Boom in Dystopian Fiction for Young Readers?” The New Yorker, June 14. Retrieved December 26, 2011 (http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2010/06/14/100614crat_atlarge_miller).

Mullins, Dexter. 2014. “New Orleans to Be Home to Nation’s First All-Charter School District.” Al Jazeera America. Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/4/4/new-orleans-charterschoolseducationreformracesegregation.html).

National Conference of State Legislatures 2022. State Medical Cannabis Laws 5/27/2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

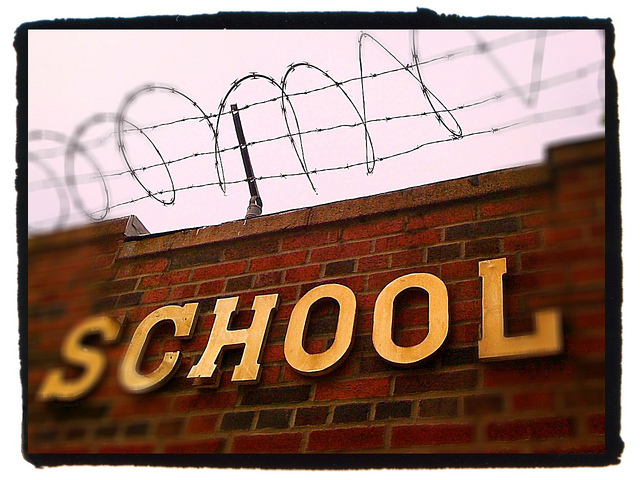

Robers, Simone, Jana Kemp, Jennifer, Truman, and Thomas D. Snyder. 2013. Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2012. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013036.pdf).

Sullivan, Melissa. 2005. “How New Orleans’ Evacuation Plan Fell Apart.” NPR. Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4860776).

Wikia. 2014. “List of Environmental Organizations.” Retrieved December 18, 2014 (http://green.wikia.com/wiki/List_of_Environmental_organizations).