8 Introduction to Marriage and Family

Rebecca and John were having a large church wedding attended by family and friends. They had been living together their entire senior year of college and planned on getting married right after graduation.

Rebecca’s parents were very traditional in their life and family. They had married after college at which time Rebecca’s mother was a stay-at-home mother and Rebecca’s father was a Vice President at a large accounting firm. The marriage was viewed as very strong by outsiders.

John’s parents had divorced when John was five. He and his younger sister lived with his financially struggling mother. The mother had a live-in boyfriend that she married when John was in high school. The Asian stepfather was helpful in getting John summer jobs and encouraged John to attend the local community college before moving to the four-year university.

Rebecca’s maid of honor, Susie, attended college with Rebecca but dropped out after finding out she was pregnant. She chose not to marry the father and was currently raising the child as a single parent. Working and taking care of the child made college a remote possibility.

The best man, Brad, was in and out of relationships. He was currently seeing a woman with several children of different parentage. The gossip had this relationship lasting about the same amount of time as all the previous encounters.

Rebecca and John had a gay couple as ushers. Steve and Roger had been in a monogamous relationship for almost ten years, had adopted a minority daughter, and were starting a web-based business together. It was obvious they both adored their child, and they planned on being married at a Washington destination ceremony later in the year.

This scenario may be complicated, but it is representative of the many types of families in today’s society.

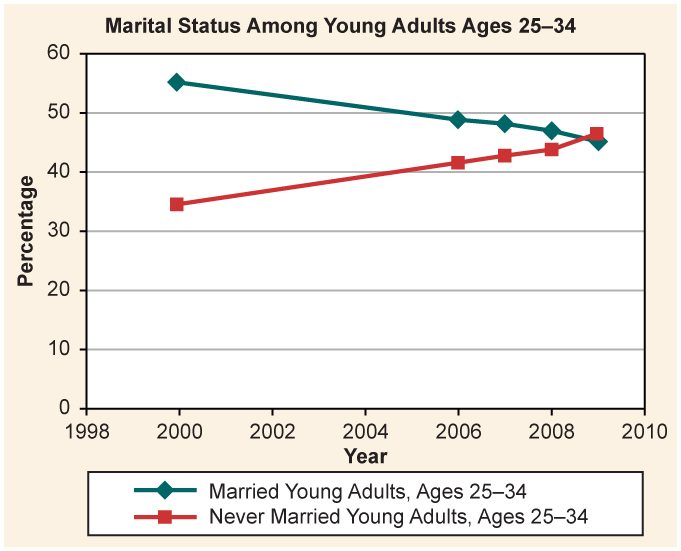

Between 2006 and 2010, nearly half of heterosexual women (48 percent) ages fifteen to forty-four said they were not married to their spouse or partner when they first lived with them, the report says. That’s up from 43 percent in 2002, and 34 percent in 1995 (Rettner 2013). The U.S. Census Bureau reports that the number of unmarried couples has grown from fewer than one million in the 1970s to 8.1 million in 2011. Cohabitating, but unwed, couples account for 10 percent of all opposite-sex couples in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2008). Some may never choose to wed (Gardner 2013). With fewer couples marrying, the traditional U.S. family structure is becoming less common. In more recent studies, the number of unmarried partners living together in the United States nearly tripled in two decades, from 6 million to 17 million (Census.gov, 2019).

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

Learning Objectives

- Describe society’s current understanding of family

- Recognize changes in marriage and family patterns

- Differentiate between lines of descent and residence

Marriage and family are key structures in most societies. While the two institutions have historically been closely linked in U.S. culture, their connection is becoming more complex. The relationship between marriage and family is an interesting topic of study to sociologists.

What is marriage? Different people define it in different ways. Not even sociologists are able to agree on a single meaning. For our purposes, we’ll define marriage as a legally recognized social contract between two people, traditionally based on a sexual relationship and implying a permanence of the union. In practicing cultural relativism, we should also consider variations, such as whether a legal union is required (think of “common law” marriage and its equivalents), or whether more than two people can be involved (consider polygamy). Other variations on the definition of marriage might include whether spouses are of opposite sexes or the same sex and how one of the traditional expectations of marriage (to produce children) is understood today.

Sociologists are interested in the relationship between the institution of marriage and the institution of family because, historically, marriages are what create families, and families are the most basic social unit upon which society is built. Both marriage and family create status roles that are sanctioned by society.

So what is a family? A husband, a wife, and two children—maybe even a pet—has served as the model for the traditional U.S. family for most of the twentieth century. But what about families that deviate from this model, such as a single-parent household or a homosexual couple without children? Should they be considered families as well?

The question of what constitutes a family is a prime area of debate in family sociology, as well as in politics and religion. Social conservatives tend to define the family in terms of structure with each family member filling a certain role (like father, mother, or child). Sociologists, on the other hand, tend to define family more in terms of the manner in which members relate to one another than on a strict configuration of status roles. Here, we’ll define family as a socially recognized group (usually joined by blood, marriage, cohabitation, or adoption) that forms an emotional connection and serves as an economic unit of society. Sociologists identify different types of families based on how one enters into them. A family of orientation refers to the family into which a person is born. A family of procreation describes one that is formed through marriage. These distinctions have cultural significance related to issues of lineage.

Drawing on two sociological paradigms, the sociological understanding of what constitutes a family can be explained by symbolic interactionism as well as functionalism. These two theories indicate that families are groups in which participants view themselves as family members and act accordingly. In other words, families are groups in which people come together to form a strong primary group connection and maintain emotional ties to one another over a long period of time. Such families may include groups of close friends or teammates. In addition, the functionalist perspective views families as groups that perform vital roles for society—both internally (for the family itself) and externally (for society as a whole). Families provide for one another’s physical, emotional, and social well-being. Parents care for and socialize children. Later in life, adult children often care for elderly parents. While interactionism helps us understand the subjective experience of belonging to a “family,” functionalism illuminates the many purposes of families and their roles in the maintenance of a balanced society (Parsons and Bales 1956). We will go into more detail about how these theories apply to family in the following pages.

Challenges Families Face

People in the United States as a whole are somewhat divided when it comes to determining what does and what does not constitute a family. In a 2010 survey conducted by professors at the University of Indiana, nearly all participants (99.8 percent) agreed that a husband, wife, and children constitute a family. Ninety-two percent stated that a husband and a wife without children still constitute a family. The numbers drop for less traditional structures: unmarried couples with children (83 percent), unmarried couples without children (39.6 percent), gay male couples with children (64 percent), and gay male couples without children (33 percent) (Powell et al. 2010). This survey revealed that children tend to be the key indicator in establishing “family” status: the percentage of individuals who agreed that unmarried couples and gay couples constitute a family nearly doubled when children were added.

The study also revealed that 60 percent of U.S. respondents agreed that if you consider yourself a family, you are a family (a concept that reinforces an interactionist perspective) (Powell 2010). The government, however, is not so flexible in its definition of “family.” The U.S. Census Bureau defines a family as “a group of two people or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together” (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). While this structured definition can be used as a means to consistently track family-related patterns over several years, it excludes individuals such as cohabitating unmarried heterosexual and homosexual couples. Legality aside, sociologists would argue that the general concept of family is more diverse and less structured than in years past. Society has given more leeway to the design of a family, making room for what works for its members (Jayson 2010).

Family is, indeed, a subjective concept, but it is a fairly objective fact that family (whatever one’s concept of it may be) is very important to people in the United States. In a 2010 survey by Pew Research Center in Washington, DC, 76 percent of adults surveyed stated that family is “the most important” element of their life—just one percent said it was “not important” (Pew Research Center 2010). It is also very important to society. President Ronald Regan notably stated, “The family has always been the cornerstone of American society. Our families nurture, preserve, and pass on to each succeeding generation the values we share and cherish, values that are the foundation of our freedoms” (Lee 2009). While the design of the family may have changed in recent years, the fundamentals of emotional closeness and support are still present. Most responders to the Pew survey stated that their family today is at least as close (45 percent) or closer (40 percent) than the family with which they grew up (Pew Research Center 2010).

Alongside the debate surrounding what constitutes a family is the question of what people in the United States believe constitutes a marriage. Many religious and social conservatives believe that marriage can only exist between a man and a woman, citing religious scripture and the basics of human reproduction as support. Social liberals and progressives, on the other hand, believe that marriage can exist between two consenting adults—be they a man and a woman, or a woman and a woman—and that it would be discriminatory to deny such a couple the civil, social, and economic benefits of marriage.

Marriage Patterns

With single parenting and cohabitation (when a couple shares a residence but not a marriage) becoming more acceptable in recent years, people may be less motivated to get married. In a recent survey, 39 percent of respondents answered “yes” when asked whether marriage is becoming obsolete (Pew Research Center 2010). The institution of marriage is likely to continue, but some previous patterns of marriage will become outdated as new patterns emerge. In this context, cohabitation contributes to the phenomenon of people getting married for the first time at a later age than was typical in earlier generations (Glezer 1991). Furthermore, marriage will continue to be delayed as more people place education and career ahead of “settling down.”

One Partner or Many?

People in the United States typically equate marriage with monogamy, when someone is married to only one person at a time. In many countries and cultures around the world, however, having one spouse is not the only form of marriage. In a majority of cultures (78 percent), polygamy, or being married to more than one person at a time, is accepted (Murdock 1967), with most polygamous societies existing in northern Africa and east Asia (Altman and Ginat 1996). Instances of polygamy are almost exclusively in the form of polygyny. Polygyny refers to a man being married to more than one woman at the same time. The reverse, when a woman is married to more than one man at the same time, is called polyandry. It is far less common and only occurs in about 1 percent of the world’s cultures (Altman and Ginat 1996). The reasons for the overwhelming prevalence of polygamous societies are varied but they often include issues of population growth, religious ideologies, and social status.

While the majority of societies accept polygyny, the majority of people do not practice it. Often fewer than 10 percent (and no more than 25–35 percent) of men in polygamous cultures have more than one wife; these husbands are often older, wealthy, high-status men (Altman and Ginat 1996). The average plural marriage involves no more than three wives. Negev Bedouin men in Israel, for example, typically have two wives, although it is acceptable to have up to four (Griver 2008). As urbanization increases in these cultures, polygamy is likely to decrease as a result of greater access to mass media, technology, and education (Altman and Ginat 1996).

In the United States, polygamy is considered by most to be socially unacceptable, and it is illegal. The act of entering into marriage while still married to another person is referred to as bigamy and is considered a felony in most states. Polygamy in the United States is often associated with those of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, although in 1890 the church officially renounced polygamy. Fundamentalist Mormons, such as those in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (a separate and distinct organization), on the other hand, still hold tightly to the historic beliefs and practices and allow polygamy in their sect.

The prevalence of polygamy among Latter-day Saints is often overestimated due to sensational media stories such as the Yearning for Zion ranch raid in Texas in 2008 and popular television shows such as HBO’s Big Love and TLC’s Sister Wives. It is estimated that there are about 37,500 fundamentalist Mormons involved in polygamy in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, but that number has shown a steady decrease in the last 100 years (Useem 2007).

U.S. Muslims, however, are an emerging group with an estimated 20,000 practicing polygamy. Again, polygamy among U.S. Muslims is uncommon and occurs only in approximately 1 percent of the population (Useem 2007). For now polygamy among U.S. Muslims has gone fairly unnoticed by mainstream society, but like fundamentalist Mormons whose practices were off the public’s radar for decades, they may someday find themselves at the center of social debate.

Residency and Lines of Descent

When considering one’s lineage, most people in the United States look to both their father’s and mother’s sides. Both paternal and maternal ancestors are considered part of one’s family. This pattern of tracing kinship is called bilateral descent. Note that kinship, or one’s traceable ancestry, can be based on blood or marriage or adoption. Sixty percent of societies, mostly modernized nations, follow a bilateral descent pattern. Unilateral descent (the tracing of kinship through one parent only) is practiced in the other 40 percent of the world’s societies, with a high concentration in pastoral cultures (O’Neal 2006).

There are three types of unilateral descent: patrilineal, which follows the father’s line only; matrilineal, which follows the mother’s side only; and ambilineal, which follows either the father’s only or the mother’s side only, depending on the situation. In patrilineal societies, such as those in rural China and India, only males carry on the family surname. This gives males the prestige of permanent family membership while females are seen as only temporary members (Harrell 2001). U.S. society assumes some aspects of patrilineal descent. For instance, most children assume their father’s last name even if the mother retains her birth name.

In matrilineal societies, inheritance and family ties are traced to women. Matrilineal descent is common in Native American societies, notably the Crow and Cherokee tribes. In these societies, children are seen as belonging to the women and, therefore, one’s kinship is traced to one’s mother, grandmother, great grandmother, and so on (Mails 1996). In ambilineal societies, which are most common in Southeast Asian countries, parents may choose to associate their children with the kinship of either the mother or the father. This choice may be based on the desire to follow stronger or more prestigious kinship lines or on cultural customs such as men following their father’s side and women following their mother’s side (Lambert 2009).

Tracing one’s line of descent to one parent rather than the other can be relevant to the issue of residence. In many cultures, newly married couples move in with, or near to, family members. In a patrilocal residence system it is customary for the wife to live with (or near) her husband’s blood relatives (or family of orientation). Patrilocal systems can be traced back thousands of years. In a DNA analysis of 4,600-year-old bones found in Germany, scientists found indicators of patrilocal living arrangements (Haak et al 2008). Patrilocal residence is thought to be disadvantageous to women because it makes them outsiders in the home and community; it also keeps them disconnected from their own blood relatives. In China, where patrilocal and patrilineal customs are common, the written symbols for maternal grandmother (wáipá) are separately translated to mean “outsider” and “women” (Cohen 2011).

Similarly, in matrilocal residence systems, where it is customary for the husband to live with his wife’s blood relatives (or her family of orientation), the husband can feel disconnected and can be labeled as an outsider. The Minangkabau people, a matrilocal society that is indigenous to the highlands of West Sumatra in Indonesia, believe that home is the place of women and they give men little power in issues relating to the home or family (Joseph and Najmabadi 2003). Most societies that use patrilocal and patrilineal systems are patriarchal, but very few societies that use matrilocal and matrilineal systems are matriarchal, as family life is often considered an important part of the culture for women, regardless of their power relative to men.

Stages of Family Life

As we’ve established, the concept of family has changed greatly in recent decades. Historically, it was often thought that many families evolved through a series of predictable stages. Developmental or “stage” theories used to play a prominent role in family sociology (Strong and DeVault 1992). Today, however, these models have been criticized for their linear and conventional assumptions as well as for their failure to capture the diversity of family forms. While reviewing some of these once-popular theories, it is important to identify their strengths and weaknesses.

The set of predictable steps and patterns families experience over time is referred to as the family life cycle. One of the first designs of the family life cycle was developed by Paul Glick in 1955. In Glick’s original design, he asserted that most people will grow up, establish families, rear and launch their children, experience an “empty nest” period, and come to the end of their lives. This cycle will then continue with each subsequent generation (Glick 1989). Glick’s colleague, Evelyn Duvall, elaborated on the family life cycle by developing these classic stages of family (Strong and DeVault 1992):

| Stage | Family Type | Children |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marriage Family | Childless |

| 2 | Procreation Family | Children ages 0 to 2.5 |

| 3 | Preschooler Family | Children ages 2.5 to 6 |

| 4 | School-age Family | Children ages 6–13 |

| 5 | Teenage Family | Children ages 13–20 |

| 6 | Launching Family | Children begin to leave home |

| 7 | Empty Nest Family | “Empty nest”; adult children have left home |

The family life cycle was used to explain the different processes that occur in families over time. Sociologists view each stage as having its own structure with different challenges, achievements, and accomplishments that transition the family from one stage to the next. For example, the problems and challenges that a family experiences in Stage 1 as a married couple with no children are likely much different than those experienced in Stage 5 as a married couple with teenagers. The success of a family can be measured by how well they adapt to these challenges and transition into each stage. While sociologists use the family life cycle to study the dynamics of family over time, consumer and marketing researchers have used it to determine what goods and services families need as they progress through each stage (Murphy and Staples 1979).

As early “stage” theories have been criticized for generalizing family life and not accounting for differences in gender, ethnicity, culture, and lifestyle, less rigid models of the family life cycle have been developed. One example is the family life course, which recognizes the events that occur in the lives of families but views them as parting terms of a fluid course rather than in consecutive stages (Strong and DeVault 1992). This type of model accounts for changes in family development, such as the fact that in today’s society, childbearing does not always occur with marriage. It also sheds light on other shifts in the way family life is practiced. Society’s modern understanding of family rejects rigid “stage” theories and is more accepting of new, fluid models.

Sociology in the Real World

The Evolution of Television Families

Whether you grew up watching the Cleavers, the Waltons, the Huxtables, or the Simpsons, most of the iconic families you saw in television sitcoms included a father, a mother, and children cavorting under the same roof while comedy ensued. The 1960s were the height of the suburban U.S. nuclear family on television with shows such as The Donna Reed Show and Father Knows Best. While some shows of this era portrayed single parents (My Three Sons and Bonanza, for instance), the single status almost always resulted from being widowed—not divorced or unwed.

Although family dynamics in real U.S. homes were changing, the expectations for families portrayed on television were not. The United States’ first reality show, An American Family (which aired on PBS in 1973) chronicled Bill and Pat Loud and their children as a “typical” U.S. family. During the series, the oldest son, Lance, announced to the family that he was gay, and at the series’ conclusion, Bill and Pat decided to divorce. Although the Louds’ union was among the 30 percent of marriages that ended in divorce in 1973, the family was featured on the cover of the March 12 issue of Newsweek with the title “The Broken Family” (Ruoff 2002).

Less traditional family structures in sitcoms gained popularity in the 1980s with shows such as Diff’rent Strokes (a widowed man with two adopted African American sons) and One Day at a Time (a divorced woman with two teenage daughters). Still, traditional families such as those in Family Ties and The Cosby Show dominated the ratings. The late 1980s and the 1990s saw the introduction of the dysfunctional family. Shows such as Roseanne, Married with Children, and The Simpsons portrayed traditional nuclear families, but in a much less flattering light than those from the 1960s did (Museum of Broadcast Communications 2011).

Over the past ten years, the nontraditional family has become somewhat of a tradition in television. While most situation comedies focus on single men and women without children, those that do portray families often stray from the classic structure: they include unmarried and divorced parents, adopted children, gay couples, and multigenerational households. Even those that do feature traditional family structures may show less-traditional characters in supporting roles, such as the brothers in the highly rated shows Everybody Loves Raymond and Two and a Half Men. Even wildly popular children’s programs such as Disney’s Hannah Montana and The Suite Life of Zack & Cody feature single parents.

In 2009, ABC premiered an intensely nontraditional family with the broadcast of Modern Family. The show follows an extended family that includes a divorced and remarried father with one stepchild and his biological adult children—one of whom is in a traditional two-parent household, and the other is a gay man in a committed relationship raising an adopted daughter. While this dynamic may be more complicated than the typical “modern” family, its elements may resonate with many of today’s viewers. “The families on the shows aren’t as idealistic, but they remain relatable,” states television critic Maureen Ryan. “The most successful shows, comedies especially, have families that you can look at and see parts of your family in them” (Respers France 2010).

8.2 Variations in Family Life

Learning Objectives

- Recognize variations in family life

- Understand the prevalence of single parents, cohabitation, same-sex couples, and unmarried individuals

- Discuss the social impact of changing family structures

The combination of husband, wife, and children that 99.8 percent of people in the United States believe constitutes a family is not representative of 99.8 percent of U.S. families. According to 2010 census data, only 66 percent of children under seventeen years old live in a household with two married parents. This is a decrease from 77 percent in 1980 (U.S. Census 2011). This two-parent family structure is known as a nuclear family, referring to married parents and children as the nucleus, or core, of the group. Recent years have seen a rise in variations of the nuclear family with the parents not being married. Three percent of children live with two cohabiting parents (U.S. Census 2011).

Single Parents

Single-parent households are on the rise. In 2010, 27 percent of children lived with a single parent only, up from 25 percent in 2008. Of that 27 percent, 23 percent live with their mother and 3 percent live with their father. Ten percent of children living with their single mother and 20 percent of children living with their single father also live with the cohabitating partner of their parent (for example, boyfriends or girlfriends).

Stepparents are an additional family element in two-parent homes. Among children living in two-parent households, 9 percent live with a biological or adoptive parent and a stepparent. The majority (70 percent) of those children live with their biological mother and a stepfather. Family structure has been shown to vary with the age of the child. Older children (fifteen to seventeen years old) are less likely to live with two parents than adolescent children (six to fourteen years old) or young children (zero to five years old). Older children who do live with two parents are also more likely to live with stepparents (U.S. Census 2011).

In some family structures a parent is not present at all. In 2010, three million children (4 percent of all children) lived with a guardian who was neither their biological nor adoptive parent. Of these children, 54 percent live with grandparents, 21 percent live with other relatives, and 24 percent live with nonrelatives. This family structure is referred to as the extended family, and may include aunts, uncles, and cousins living in the same home. Foster parents account for about a quarter of nonrelatives. The practice of grandparents acting as parents, whether alone or in combination with the child’s parent, is becoming widespread among today’s families (De Toledo and Brown 1995). Nine percent of all children live with a grandparent, and in nearly half those cases, the grandparent maintains primary responsibility for the child (U.S. Census 2011). A grandparent functioning as the primary care provider often results from parental drug abuse, incarceration, or abandonment. Events like these can render the parent incapable of caring for his or her child.

Changes in the traditional family structure raise questions about how such societal shifts affect children. U.S. Census statistics have long shown that children living in homes with both parents grow up with more financial and educational advantages than children who are raised in single-parent homes (U.S. Census 1997). Parental marital status seems to be a significant indicator of advancement in a child’s life. Children living with a divorced parent typically have more advantages than children living with a parent who never married; this is particularly true of children who live with divorced fathers. This correlates with the statistic that never-married parents are typically younger, have fewer years of schooling, and have lower incomes (U.S. Census 1997). Six in ten children living with only their mother live near or below the poverty level. Of those being raised by single mothers, 69 percent live in or near poverty compared to 45 percent for divorced mothers (U.S. Census 1997). Though other factors such as age and education play a role in these differences, it can be inferred that marriage between parents is generally beneficial for children.

Cohabitation

Living together before or in lieu of marriage is a growing option for many couples. Cohabitation, when a man and woman live together in a sexual relationship without being married, was practiced by an estimated 7.5 million people (11.5 percent of the population) in 2011, which shows an increase of 13 percent since 2009 (U.S. Census 2010). This surge in cohabitation is likely due to the decrease in social stigma pertaining to the practice. In a 2010 National Center for Health Statistics survey, only 38 percent of the 13,000-person sample thought that cohabitation negatively impacted society (Jayson 2010). Of those who cohabitate, the majority are non-Hispanic with no high school diploma or GED and grew up in a single-parent household (U.S. Census 2010).

Cohabitating couples may choose to live together in an effort to spend more time together or to save money on living costs. Many couples view cohabitation as a “trial run” for marriage. Today, approximately 28 percent of men and women cohabitated before their first marriage. By comparison, 18 percent of men and 23 percent of women married without ever cohabitating (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The vast majority of cohabitating relationships eventually result in marriage; only 15 percent of men and women cohabitate only and do not marry. About one half of cohabitators transition into marriage within three years (U.S. Census 2010).

While couples may use this time to “work out the kinks” of a relationship before they wed, the most recent research has found that cohabitation has little effect on the success of a marriage. In fact, those who do not cohabitate before marriage have slightly better rates of remaining married for more than ten years (Jayson 2010). Cohabitation may contribute to the increase in the number of men and women who delay marriage. The median age for marriage is the highest it has ever been since the U.S. Census kept records—age twenty-six for women and age twenty-eight for men (U.S. Census 2010).

Same-Sex Couples

The number of same-sex couples has grown significantly in the past decade. The U.S. Census Bureau reported 594,000 same-sex couple households in the United States, a 50 percent increase from 2000. This increase is a result of more coupling, the growing social acceptance of homosexuality, and a subsequent increase in willingness to report it. Nationally, same-sex couple households make up 1 percent of the population, ranging from as little as 0.29 percent in Wyoming to 4.01 percent in the District of Columbia (U.S. Census 2011). Legal recognition of same-sex couples as spouses is different in each state, as only six states and the District of Columbia have legalized same-sex marriage. The 2010 U.S. Census, however, allowed same-sex couples to report as spouses regardless of whether their state legally recognizes their relationship. Nationally, 25 percent of all same-sex households reported that they were spouses. In states where same-sex marriages are performed, nearly half (42.4 percent) of same-sex couple households were reported as spouses.

In terms of demographics, same-sex couples are not very different from opposite-sex couples. Same-sex couple households have an average age of 52 and an average household income of $91,558; opposite-sex couple households have an average age of 59 and an average household income of $95,075. Additionally, 31 percent of same-sex couples are raising children, not far from the 43 percent of opposite-sex couples (U.S. Census 2009). Of the children in same-sex couple households, 73 percent are biological children (of only one of the parents), 21 percent are adopted only, and 6 percent are a combination of biological and adopted (U.S. Census 2009).

While there is some concern from socially conservative groups regarding the well-being of children who grow up in same-sex households, research reports that same-sex parents are as effective as opposite-sex parents. In an analysis of 81 parenting studies, sociologists found no quantifiable data to support the notion that opposite-sex parenting is any better than same-sex parenting. Children of lesbian couples, however, were shown to have slightly lower rates of behavioral problems and higher rates of self-esteem (Biblarz and Stacey 2010).

Staying Single

Gay or straight, a new option for many people in the United States is simply to stay single. In 2010, there were 99.6 million unmarried individuals over age eighteen in the United States, accounting for 44 percent of the total adult population (U.S. Census 2011). In 2010, never-married individuals in the twenty-five to twenty-nine age bracket accounted for 62 percent of women and 48 percent of men, up from 11 percent and 19 percent, respectively, in 1970 (U.S. Census 2011). Single, or never-married, individuals are found in higher concentrations in large cities or metropolitan areas, with New York City being one of the highest.

Although both single men and single women report social pressure to get married, women are subject to greater scrutiny. Single women are often portrayed as unhappy “spinsters” or “old maids” who cannot find a man to marry them. Single men, on the other hand, are typically portrayed as lifetime bachelors who cannot settle down or simply “have not found the right girl.” Single women report feeling insecure and displaced in their families when their single status is disparaged (Roberts 2007). However, single women older than thirty-five years old report feeling secure and happy with their unmarried status, as many women in this category have found success in their education and careers. In general, women feel more independent and more prepared to live a large portion of their adult lives without a spouse or domestic partner than they did in the 1960s (Roberts 2007).

The decision to marry or not to marry can be based on a variety of factors including religion and cultural expectations. Asian individuals are the most likely to marry while African Americans are the least likely to marry (Venugopal 2011). Additionally, individuals who place no value on religion are more likely to be unmarried than those who place a high value on religion. For black women, however, the importance of religion made no difference in marital status (Bakalar 2010). In general, being single is not a rejection of marriage; rather, it is a lifestyle that does not necessarily include marriage. By age forty, according to census figures, 20 percent of women and 14 of men will have never married (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

Sociological Research

Deceptive Divorce Rates

It is often cited that half of all marriages end in divorce. This statistic has made many people cynical when it comes to marriage, but it is misleading. Let’s take a closer look at the data.

Using National Center for Health Statistics data from 2003 that show a marriage rate of 7.5 (per 1000 people) and a divorce rate of 3.8, it would appear that exactly one half of all marriages failed (Hurley 2005). This reasoning is deceptive, however, because instead of tracing actual marriages to see their longevity (or lack thereof), this compares what are unrelated statistics: that is, the number of marriages in a given year does not have a direct correlation to the divorces occurring that same year. Research published in the New York Times took a different approach—determining how many people had ever been married, and of those, how many later divorced. The result? According to this analysis, U.S. divorce rates have only gone as high as 41 percent (Hurley 2005). Another way to calculate divorce rates would be through a cohort study. For instance, we could determine the percentage of marriages that are intact after, say, five or seven years, compared to marriages that have ended in divorce after five or seven years. Sociological researchers must remain aware of research methods and how statistical results are applied. As illustrated, different methodologies and different interpretations can lead to contradictory, and even misleading, results.

Theoretical Perspectives on Marriage and Family

Sociologists study families on both the macro and micro levels to determine how families function. Sociologists may use a variety of theoretical perspectives to explain events that occur within and outside of the family.

Functionalism

When considering the role of family in society, functionalists uphold the notion that families are an important social institution and that they play a key role in stabilizing society. They also note that family members take on status roles in a marriage or family. The family—and its members—performs certain functions that facilitate the prosperity and development of society.

Sociologist George Murdock conducted a survey of 250 societies and determined that there are four universal residual functions of the family: sexual, reproductive, educational, and economic (Lee 1985). According to Murdock, the family (which for him includes the state of marriage) regulates sexual relations between individuals. He does not deny the existence or impact of premarital or extramarital sex but states that the family offers a socially legitimate sexual outlet for adults (Lee 1985). This outlet gives way to reproduction, which is a necessary part of ensuring the survival of society.

Once children are produced, the family plays a vital role in training them for adult life. As the primary agent of socialization and enculturation, the family teaches young children the ways of thinking and behaving that follow social and cultural norms, values, beliefs, and attitudes. Parents teach their children manners and civility. A well-mannered child reflects a well-mannered parent.

Parents also teach children gender roles. Gender roles are an important part of the economic function of a family. In each family, there is a division of labor that consists of instrumental and expressive roles. Men tend to assume the instrumental roles in the family, which typically involve work outside of the family that provides financial support and establishes family status. Women tend to assume the expressive roles, which typically involve work inside of the family that provides emotional support and physical care for children (Crano and Aronoff 1978). According to functionalists, the differentiation of the roles on the basis of sex ensures that families are well balanced and coordinated. When family members move outside of these roles, the family is thrown out of balance and must recalibrate in order to function properly. For example, if the father assumes an expressive role such as providing daytime care for the children, the mother must take on an instrumental role such as gaining paid employment outside of the home in order for the family to maintain balance and function.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists are quick to point out that U.S. families have been defined as private entities, the consequence of which has been to leave family matters to only those within the family. Many people in the United States are resistant to government intervention in the family: parents do not want the government to tell them how to raise their children or to become involved in domestic issues. Conflict theory highlights the role of power in family life and contends that the family is often not a haven but rather an arena where power struggles can occur. This exercise of power often entails the performance of family status roles. Conflict theorists may study conflicts as simple as the enforcement of rules from parent to child, or they may examine more serious issues such as domestic violence (spousal and child), sexual assault, marital rape, and incest.

The first study of marital power was performed in 1960. Researchers found that the person with the most access to value resources held the most power. As money is one of the most valuable resources, men who worked in paid labor outside of the home held more power than women who worked inside the home (Blood and Wolfe 1960). Conflict theorists find disputes over the division of household labor to be a common source of marital discord. Household labor offers no wages and, therefore, no power. Studies indicate that when men do more housework, women experience more satisfaction in their marriages, reducing the incidence of conflict (Coltrane 2000). In general, conflict theorists tend to study areas of marriage and life that involve inequalities or discrepancies in power and authority, as they are reflective of the larger social structure.

Symbolic Interactionism

Interactionists view the world in terms of symbols and the meanings assigned to them (LaRossa and Reitzes 1993). The family itself is a symbol. To some, it is a father, mother, and children; to others, it is any union that involves respect and compassion. Interactionists stress that family is not an objective, concrete reality. Like other social phenomena, it is a social construct that is subject to the ebb and flow of social norms and ever-changing meanings.

Consider the meaning of other elements of family: “parent” was a symbol of a biological and emotional connection to a child; with more parent-child relationships developing through adoption, remarriage, or change in guardianship, the word “parent” today is less likely to be associated with a biological connection than with whoever is socially recognized as having the responsibility for a child’s upbringing. Similarly, the terms “mother” and “father” are no longer rigidly associated with the meanings of caregiver and breadwinner. These meanings are more free-flowing through changing family roles.

Interactionists also recognize how the family status roles of each member are socially constructed, playing an important part in how people perceive and interpret social behavior. Interactionists view the family as a group of role players or “actors” that come together to act out their parts in an effort to construct a family. These roles are up for interpretation. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a “good father,” for example, was one who worked hard to provide financial security for his children. Today, a “good father” is one who takes the time outside of work to promote his children’s emotional well-being, social skills, and intellectual growth—in some ways, a much more daunting task.

8.3 Challenges Families Face

Learning Objectives

- Understand the social and interpersonal impact of divorce

- Describe the social and interpersonal impact of family abuse

As the structure of family changes over time, so do the challenges families face. Events like divorce and remarriage present new difficulties for families and individuals. Other long-standing domestic issues such as abuse continue to strain the health and stability of today’s families.

Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce, while fairly common and accepted in modern U.S. society, was once a word that would only be whispered and was accompanied by gestures of disapproval. In 1960, divorce was generally uncommon, affecting only 9.1 out of every 1,000 married persons. That number more than doubled (to 20.3) by 1975 and peaked in 1980 at 22.6 (Popenoe 2007). Over the last quarter century, divorce rates have dropped steadily and are now similar to those in 1970. The dramatic increase in divorce rates after the 1960s has been associated with the liberalization of divorce laws as well as the shift in societal makeup due to women increasingly entering the workforce (Michael 1978). The decrease in divorce rates can be attributed to two probable factors: an increase in the age at which people get married, and an increased level of education among those who marry—both of which have been found to promote greater marital stability.

Divorce does not occur equally among all people in the United States; some segments of the U.S. population are more likely to divorce than others. According to the American Community Survey (ACS), men and women in the Northeast have the lowest rates of divorce at 7.2 and 7.5 per 1,000 people. The South has the highest rate of divorce at 10.2 for men and 11.1 for women. Divorce rates are likely higher in the South because marriage rates are higher and marriage occurs at younger-than-average ages in this region. In the Northeast, the marriage rate is lower and first marriages tend to be delayed; therefore, the divorce rate is lower (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

The rate of divorce also varies by race. In a 2009 ACS study, American Indian and Alaskan Natives reported the highest percentages of currently divorced individuals (12.6 percent) followed by blacks (11.5 percent), whites (10.8 percent), Pacific Islanders (8 percent), Latinos (7.8 percent), and Asians (4.9 percent) (ACS 2011). In general those who marry at a later age and have a college education have lower rates of divorce.

| Year | Divorces and annulments | Population | Rate per 1,000 total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20111 | 877,000 | 246,273,366 | 3.6 |

| 20101 | 872,000 | 244,122,529 | 3.6 |

| 20091 | 840,000 | 242,610,561 | 3.5 |

| 20081 | 844,000 | 240,545,163 | 3.5 |

| 20071 | 856,000 | 238,352,850 | 3.6 |

| 20061 | 872,000 | 236,094,277 | 3.7 |

| 20051 | 847,000 | 233,495,163 | 3.6 |

| 20042 | 879,000 | 236,402,656 | 3.7 |

| 20033 | 927,000 | 243,902,090 | 3.8 |

| 20024 | 955,000 | 243,108,303 | 3.9 |

| 20015 | 940,000 | 236,416,762 | 4.0 |

| 20005 | 944,000 | 233,550,143 | 4.0 |

1Excludes data for California, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, and Minnesota.

2Excludes data for California, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, and Louisiana.

3Excludes data for California, Hawaii, Indiana, and Oklahoma.

4Excludes data for California, Indiana, and Oklahoma.

5Excludes data for California, Indiana, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

Note: Rates for 2001–2009 have been revised and are based on intercensal population estimates from the 2000 and 2010 censuses. Populations for 2010 rates are based on the 2010 census.

So what causes divorce? While more young people are choosing to postpone or opt out of marriage, those who enter into the union do so with the expectation that it will last. A great deal of marital problems can be related to stress, especially financial stress. According to researchers participating in the University of Virginia’s National Marriage Project, couples who enter marriage without a strong asset base (like a home, savings, and a retirement plan) are 70 percent more likely to be divorced after three years than are couples with at least $10,000 in assets. This is connected to factors such as age and education level that correlate with low incomes.

The addition of children to a marriage creates added financial and emotional stress. Research has established that marriages enter their most stressful phase upon the birth of the first child (Popenoe and Whitehead 2007). This is particularly true for couples who have multiples (twins, triplets, and so on). Married couples with twins or triplets are 17 percent more likely to divorce than those with children from single births (McKay 2010). Another contributor to the likelihood of divorce is a general decline in marital satisfaction over time. As people get older, they may find that their values and life goals no longer match up with those of their spouse (Popenoe and Whitehead 2004).

Divorce is thought to have a cyclical pattern. Children of divorced parents are 40 percent more likely to divorce than children of married parents. And when we consider children whose parents divorced and then remarried, the likelihood of their own divorce rises to 91 percent (Wolfinger 2005). This might result from being socialized to a mindset that a broken marriage can be replaced rather than repaired (Wolfinger 2005). That sentiment is also reflected in the finding that when both partners of a married couple have been previously divorced, their marriage is 90 percent more likely to end in divorce (Wolfinger 2005).

People in a second marriage account for approximately 19.3 percent of all married persons, and those who have been married three or more times account for 5.2 percent (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). The vast majority (91 percent) of remarriages occur after divorce; only 9 percent occur after death of a spouse (Kreider 2006). Most men and women remarry within five years of a divorce, with the median length for men (three years) being lower than for women (4.4 years). This length of time has been fairly consistent since the 1950s. The majority of those who remarry are between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four (Kreider 2006). The general pattern of remarriage also shows that whites are more likely to remarry than black Americans.

Marriage the second time around (or third or fourth) can be a very different process than the first. Remarriage lacks many of the classic courtship rituals of a first marriage. In a second marriage, individuals are less likely to deal with issues like parental approval, premarital sex, or desired family size (Elliot 2010). In a survey of households formed by remarriage, a mere 8 percent included only biological children of the remarried couple. Of the 49 percent of homes that include children, 24 percent included only the woman’s biological children, 3 percent included only the man’s biological children, and 9 percent included a combination of both spouse’s children (U.S. Census Bureau 2006).

Children of Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce and remarriage can be stressful on partners and children alike. Divorce is often justified by the notion that children are better off in a divorced family than in a family with parents who do not get along. However, long-term studies determine that to be generally untrue. Research suggests that while marital conflict does not provide an ideal childrearing environment, going through a divorce can be damaging. Children are often confused and frightened by the threat to their family security. They may feel responsible for the divorce and attempt to bring their parents back together, often by sacrificing their own well-being (Amato 2000). Only in high-conflict homes do children benefit from divorce and the subsequent decrease in conflict. The majority of divorces come out of lower-conflict homes, and children from those homes are more negatively impacted by the stress of the divorce than the stress of unhappiness in the marriage (Amato 2000). Studies also suggest that stress levels for children are not improved when a child acquires a stepfamily through marriage. Although there may be increased economic stability, stepfamilies typically have a high level of interpersonal conflict (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994).

Children’s ability to deal with a divorce may depend on their age. Research has found that divorce may be most difficult for school-aged children, as they are old enough to understand the separation but not old enough to understand the reasoning behind it. Older teenagers are more likely to recognize the conflict that led to the divorce but may still feel fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to choose sides. Infants and preschool-age children may suffer the heaviest impact from the loss of routine that the marriage offered (Temke 2006).

Proximity to parents also makes a difference in a child’s well-being after divorce. Boys who live or have joint arrangements with their fathers show less aggression than those who are raised by their mothers only. Similarly, girls who live or have joint arrangements with their mothers tend to be more responsible and mature than those who are raised by their fathers only. Nearly three-fourths of the children of parents who are divorced live in a household headed by their mother, leaving many boys without a father figure residing in the home (U.S. Census Bureau 2011b). Still, researchers suggest that a strong parent-child relationship can greatly improve a child’s adjustment to divorce (Temke 2006).

There is empirical evidence that divorce has not discouraged children in terms of how they view marriage and family. A blended family has additional stress resulting from combining children from the current and previous relationships. The blended family also has an ex-parent who has different discipline techniques. In a survey conducted by researchers from the University of Michigan, about three-quarters of high school seniors said it was “extremely important” to have a strong marriage and family life. And over half believed it was “very likely” that they would be in a lifelong marriage (Popenoe and Whitehead 2007). These numbers have continued to climb over the last twenty-five years.

Violence and Abuse

Violence and abuse are among the most disconcerting of the challenges that today’s families face. Abuse can occur between spouses, between parent and child, as well as between other family members. The frequency of violence among families is difficult to determine because many cases of spousal abuse and child abuse go unreported. In any case, studies have shown that abuse (reported or not) has a major impact on families and society as a whole.

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is a significant social problem in the United States. It is often characterized as violence between household or family members, specifically spouses. To include unmarried, cohabitating, and same-sex couples, family sociologists have created the term intimate partner violence (IPV). Women are the primary victims of intimate partner violence. It is estimated that one in four women has experienced some form of IPV in her lifetime (compared to one in seven men) (Catalano 2007). IPV may include physical violence, such as punching, kicking, or other methods of inflicting physical pain; sexual violence, such as rape or other forced sexual acts; threats and intimidation that imply either physical or sexual abuse; and emotional abuse, such as harming another’s sense of self-worth through words or controlling another’s behavior. IPV often starts as emotional abuse and then escalates to other forms or combinations of abuse (Centers for Disease Control 2012).

In 2010, of IPV acts that involved physical actions against women, 57 percent involved physical violence only; 9 percent involved rape and physical violence; 14 percent involved physical violence and stalking; 12 percent involved rape, physical violence, and stalking; and 4 percent involved rape only (CDC 2011). This is vastly different than IPV abuse patterns for men, which show that nearly all (92 percent) physical acts of IVP take the form of physical violence and fewer than 1 percent involve rape alone or in combination (Catalano 2007). IPV affects women at greater rates than men because women often take the passive role in relationships and may become emotionally dependent on their partners. Perpetrators of IPV work to establish and maintain such dependence in order to hold power and control over their victims, making them feel stupid, crazy, or ugly—in some way worthless.

IPV affects different segments of the population at different rates. The rate of IPV for black women (4.6 per 1,000 persons over the age of twelve) is higher than that for white women (3.1). These numbers have been fairly stable for both racial groups over the last ten years. However, the numbers have steadily increased for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives (up to 11.1 for females) (Catalano 2007).

Those who are separated report higher rates of abuse than those with other marital statuses, as conflict is typically higher in those relationships. Similarly, those who are cohabitating are more likely than those who are married to experience IPV (Stets and Straus 1990). Other researchers have found that the rate of IPV doubles for women in low-income disadvantaged areas when compared to IPV experienced by women who reside in more affluent areas (Benson and Fox 2004). Overall, women ages twenty to twenty-four are at the greatest risk of nonfatal abuse (Catalano 2007).

Accurate statistics on IPV are difficult to determine, as it is estimated that more than half of nonfatal IPV goes unreported. It is not until victims choose to report crimes that patterns of abuse are exposed. Most victims studied stated that abuse had occurred for at least two years prior to their first report (Carlson, Harris, and Holden 1999).

Sometimes abuse is reported to police by a third party, but it still may not be confirmed by victims. A study of domestic violence incident reports found that even when confronted by police about abuse, 29 percent of victims denied that abuse occurred. Surprisingly, 19 percent of their assailants were likely to admit to abuse (Felson, Ackerman, and Gallagher 2005). According to the National Criminal Victims Survey, victims cite varied reasons why they are reluctant to report abuse, as shown in the table below.

| Reason Abuse Is Unreported | % Females | % Males |

|---|---|---|

| Considered a Private Matter | 22 | 39 |

| Fear of Retaliation | 12 | 5 |

| To Protect the Abuser | 14 | 16 |

| Belief That Police Won’t Do Anything | 8 | 8 |

Two-thirds of nonfatal IPV occurs inside of the home and approximately 10 percent occurs at the home of the victim’s friend or neighbor. The majority of abuse takes place between the hours of 6 p.m. and 6 a.m., and nearly half (42 percent) involves alcohol or drug use (Catalano 2007). Many perpetrators of IVP blame alcohol or drugs for their abuse, though studies have shown that alcohol and drugs do not cause IPV, they may only lower inhibitions (Hanson 2011). IPV has significant long-term effects on individual victims and on society. Studies have shown that IPV damage extends beyond the direct physical or emotional wounds. Extended IPV has been linked to unemployment among victims, as many have difficulty finding or holding employment. Additionally, nearly all women who report serious domestic problems exhibit symptoms of major depression (Goodwin, Chandler, and Meisel 2003).

Female victims of IPV are also more likely to abuse alcohol or drugs, suffer from eating disorders, and attempt suicide (Silverman et al. 2001). IPV is indeed something that impacts more than just intimate partners. In a survey, 34 percent of respondents said they have witnessed IPV, and 59 percent said that they know a victim personally (Roper Starch Worldwide 1995). Many people want to help IPV victims but are hesitant to intervene because they feel that it is a personal matter or they fear retaliation from the abuser—reasons similar to those of victims who do not report IPV.

Child Abuse

Children are among the most helpless victims of abuse. In 2010, there were more than 3.3 million reports of child abuse involving an estimated 5.9 million children (Child Help 2011). Three-fifths of child abuse reports are made by professionals, including teachers, law enforcement personnel, and social services staff. The rest are made by anonymous sources, other relatives, parents, friends, and neighbors.

Child abuse may come in several forms, the most common being neglect (78.3 percent), followed by physical abuse (10.8 percent), sexual abuse (7.6 percent), psychological maltreatment (7.6 percent), and medical neglect (2.4 percent) (Child Help 2011). Some children suffer from a combination of these forms of abuse. The majority (81.2 percent) of perpetrators are parents; 6.2 percent are other relatives.

Infants (children less than one year old) were the most victimized population with an incident rate of 20.6 per 1,000 infants. This age group is particularly vulnerable to neglect because they are entirely dependent on parents for care. Some parents do not purposely neglect their children; factors such as cultural values, standard of care in a community, and poverty can lead to hazardous level of neglect. If information and assistance from public or private services are available and a parent fails to use those services, child welfare services may intervene (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).

Infants are also often victims of physical abuse, particularly in the form of violent shaking. This type of physical abuse is referred to as shaken-baby syndrome, which describes a group of medical symptoms such as brain swelling and retinal hemorrhage resulting from forcefully shaking or causing impact to an infant’s head. A baby’s cry is the number one trigger for shaking. Parents may find themselves unable to soothe a baby’s concerns and may take their frustration out on the child by shaking him or her violently. Other stress factors such as a poor economy, unemployment, and general dissatisfaction with parental life may contribute to this type of abuse. While there is no official central registry of shaken-baby syndrome statistics, it is estimated that each year 1,400 babies die or suffer serious injury from being shaken (Barr 2007).

Social Policy and Debate

Corporal Punishment

Physical abuse in children may come in the form of beating, kicking, throwing, choking, hitting with objects, burning, or other methods. Injury inflicted by such behavior is considered abuse even if the parent or caregiver did not intend to harm the child. Other types of physical contact that are characterized as discipline (spanking, for example) are not considered abuse as long as no injury results (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2008).

This issue is rather controversial among modern-day people in the United States. While some parents feel that physical discipline, or corporal punishment, is an effective way to respond to bad behavior, others feel that it is a form of abuse. According to a poll conducted by ABC News, 65 percent of respondents approve of spanking and 50 percent said that they sometimes spank their child.

Tendency toward physical punishment may be affected by culture and education. Those who live in the South are more likely than those who live in other regions to spank their child. Those who do not have a college education are also more likely to spank their child (Crandall 2011). Currently, 23 states officially allow spanking in the school system; however, many parents may object and school officials must follow a set of clear guidelines when administering this type of punishment (Crandall 2011). Studies have shown that spanking is not an effective form of punishment and may lead to aggression by the victim, particularly in those who are spanked at a young age (Berlin 2009).

Child abuse occurs at all socioeconomic and education levels and crosses ethnic and cultural lines. Just as child abuse is often associated with stresses felt by parents, including financial stress, parents who demonstrate resilience to these stresses are less likely to abuse (Samuels 2011). Young parents are typically less capable of coping with stresses, particularly the stress of becoming a new parent. Teenage mothers are more likely to abuse their children than their older counterparts. As a parent’s age increases, the risk of abuse decreases. Children born to mothers who are fifteen years old or younger are twice as likely to be abused or neglected by age five than are children born to mothers ages twenty to twenty-one (George and Lee 1997).

Drug and alcohol use is also a known contributor to child abuse. Children raised by substance abusers have a risk of physical abuse three times greater than other kids, and neglect is four times as prevalent in these families (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2011). Other risk factors include social isolation, depression, low parental education, and a history of being mistreated as a child. Approximately 30 percent of abused children will later abuse their own children (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2006).

The long-term effects of child abuse impact the physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing of a child. Injury, poor health, and mental instability occur at a high rate in this group, with 80 percent meeting the criteria of one or more psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, or suicidal behavior, by age twenty-one. Abused children may also suffer from cognitive and social difficulties. Behavioral consequences will affect most, but not all, child abuse victims. Children of abuse are 25 percent more likely, as adolescents, to suffer from difficulties like poor academic performance and teen pregnancy, or to engage in behaviors like drug abuse and general delinquency. They are also more likely to participate in risky sexual acts that increase their chances of contracting a sexually transmitted disease (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2006). Other risky behaviors include drug and alcohol abuse. As these consequences can affect the health care, education, and criminal systems, the problems resulting from child abuse do not just belong to the child and family, but to society as a whole.

Key Terms

- ambilineal

- a type of unilateral descent that follows either the father’s or the mother’s side exclusively

- bigamy

- the act of entering into marriage while still married to another person

- bilateral descent

- the tracing of kinship through both parents’ ancestral lines

- cohabitation

- the act of a couple sharing a residence while they are not married

- cultural relativism

- the view that a culture can only be understood and judged by the standards, behaviors, norms, and values within the culture and not by anything outside.

- extended family

- a household that includes at least one parent and child as well as other relatives like grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins

- family

- socially recognized groups of individuals who may be joined by blood, marriage, or adoption and who form an emotional connection and an economic unit of society

- family life course

- a sociological model of family that sees the progression of events as fluid rather than as occurring in strict stages

- family life cycle

- a set of predictable steps and patterns families experience over time

- family of orientation

- the family into which one is born

- family of procreation

- a family that is formed through marriage

- intimate partner violence (IPV)

- violence that occurs between individuals who maintain a romantic or sexual relationship

- kinship

- a person’s traceable ancestry (by blood, marriage, and/or adoption)

- marriage

- a legally recognized contract between two or more people in a sexual relationship who have an expectation of permanence about their relationship

- matrilineal descent

- a type of unilateral descent that follows the mother’s side only

- matrilocal residence

- a system in which it is customary for a husband to live with his wife’s family

- monogamy

- the act of being married to only one person at a time

- nuclear family

- two parents (traditionally a married husband and wife) and children living in the same household

- patrilineal descent

- a type of unilateral descent that follows the father’s line only

- patrilocal residence

- a system in which it is customary for the wife to live with (or near) her husband’s family

- polyandry

- a form of marriage in which one woman is married to more than one man at one time

- polygamy

- the state of being committed or married to more than one person at a time

- polygyny

- a form of marriage in which one man is married to more than one woman at one time

- shaken-baby syndrome

- a group of medical symptoms such as brain swelling and retinal hemorrhage resulting from forcefully shaking or impacting an infant’s head

- unilateral descent

- the tracing of kinship through one parent only.

Section Summary

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

Sociologists view marriage and families as societal institutions that help create the basic unit of social structure. Both marriage and a family may be defined differently—and practiced differently—in cultures across the world. Families and marriages, like other institutions, adapt to social change.

8.2 Variations in Family Life

People’s concepts of marriage and family in the United States are changing. Increases in cohabitation, same-sex partners, and singlehood are altering of our ideas of marriage. Similarly, single parents, same-sex parents, cohabitating parents, and unwed parents are changing our notion of what it means to be a family. While most children still live in opposite-sex, two-parent, married households, that is no longer viewed as the only type of nuclear family.

8.3 Challenges Families Face

Today’s families face a variety of challenges, specifically to marital stability. While divorce rates have decreased in the last twenty-five years, many family members, especially children, still experience the negative effects of divorce. Children are also negatively impacted by violence and abuse within the home, with nearly 6 million children abused each year.

Section Quizzes

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

1. Sociologists tend to define family in terms of

- how a given society sanctions the relationships of people who are connected through blood, marriage, or adoption

- the connection of bloodlines

- the status roles that exist in a family structure

- how closely members adhere to social norms

2. Research suggests that people generally feel that their current family is _______ than the family they grew up with.

- less close

- more close

- at least as close

- none of the above

3. A woman being married to two men would be an example of:

- monogamy

- polygyny

- polyandry

- cohabitation

4. A child who associates his line of descent with his father’s side only is part of a _____ society.

- matrilocal

- bilateral

- matrilineal

- patrilineal

5. Which of the following is a criticism of the family life cycle model?

- It is too broad and accounts for too many aspects of family.

- It is too narrowly focused on a sequence of stages.

- It does not serve a practical purpose for studying family behavior.

- It is not based on comprehensive research.

8.2 Variations in Family Life

6. The majority of U.S. children live in:

- two-parent households

- one-parent households

- no-parent households

- multigenerational households

7. According to the study cited by the U.S. Census Bureau, children who live with married parents grow up with more advantages than children who live with:

- a divorced parent

- a single parent

- a grandparent

- all of the above

8. Couples who cohabitate before marriage are ______ couples who did not cohabitate before marriage to be married for at least ten years.

- far more likely than

- far less likely than

- slightly less likely than

- equally as likely as

9. Same-sex couple households account for _____ percent of U.S. households.

- 1

- 10

- 15

- 30

10. The median age of first marriage has ______ in the last fifty years.

- increased for men but not women

- decreased for men but not women

- increased for both men and women

- decreased for both men and women

8.3 Challenges Families Face

11. Current divorce rates are:

- at an all-time high

- at an all-time low

- steadily increasing

- steadily declining

12. Children of divorced parents are _______ to divorce in their own marriage than children of parents who stayed married.

- more likely

- less likely

- equally likely

13. In general, children in ______ households benefit from divorce.

- stepfamily

- multigenerational

- high-conflict

- low-conflict

14. Which of the following is true of intimate partner violence (IPV)?

- IPV victims are more frequently men than women.

- One in ten women is a victim of IPV.

- Nearly half of instances of IPV involve drugs or alcohol.

- Rape is the most common form of IPV.

15. Which type of child abuse is most prevalent in the United States?

- Physical abuse

- Neglect

- Shaken-baby syndrome

- Verbal mistreatment

Short Answer

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

1. According to research, what are people’s general thoughts on family in the United States? How do they view nontraditional family structures? How do you think these views might change in twenty years?

2. Explain the difference between bilateral and unilateral descent. Using your own association with kinship, explain which type of descent applies to you?

8.2 Variations in Family Life

3. Explain the different variations of the nuclear family and the trends that occur in each.

4. Why are some couples choosing to cohabitate before marriage? What effect does cohabitation have on marriage?

8.3 Challenges Families Face

5. Explain how financial status impacts marital stability. What other factors are associated with a couple’s financial status?

6. Explain why more than half of IPV goes unreported. Why are those who are abused unlikely to report the abuse?

Further Research

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

For more information on family development and lines of descent, visit the New England Historical Genealogical Society’s website, American Ancestors, and find out how genealogies have been established and recorded since 1845. http://openstax.org/l/American_Ancestors

8.2 Variations in Family Life

For more statistics on marriage and family, see the Forum on Child and Family Statistics at http://openstax.org/l/child_family_statistics, as well as the American Community Survey, the Current Population Survey, and the U.S. Census decennial survey at http://openstax.org/l/US_Census.

8.3 Challenges Families Face

To find more information on child abuse, visit the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services web site at http://openstax.org/l/child_welfare to review documents provided by the Child Welfare Information Gateway.

References

Introduction to Marriage and Family

Gardner, Amanda. 2013. “More U.S. Couples Living Together Instead of Marrying, CDC Finds.” HealthDay.com. Retrieved December 29, 2014 (http://consumer.healthday.com/public-health-information-30/centers-for-disease-control-news-120/more-u-s-couples-living-together-instead-of-marrying-cdc-finds-675096.html).

Gurrentz, B. (2019). Unmarried Partners More Diverse Than 20 Years Ago. Cohabiting Partners Older, More Racially Diverse, More Educated, Higher Earners. Census.Gov. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/09/unmarried-partners-more-diverse-than-20-years-ago.html)

Rettner, Rachel. 2013. “More Couples Living Together Outside of Marriage.” MyHealthNewsDaily/Purch. Retrieved December 29, 2014 (http://www.livescience.com/28420-cohabiting-marriage-cdc-report.html).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2008. “50 Million Children Lived with Married Parents in 2007.” July 28. Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/marital_status_living_arrangements/cb08-115.html)

Useem, Andrea. 2007. “What to Expect When You’re Expecting a Co-Wife.” Slate, July 24. Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.slate.com/articles/life/faithbased/2007/07/what_to_expect_when_youre_expecting_a_cowife.html).

8.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

Altman, Irwin, and Joseph Ginat. 1996. Polygamous Families in Contemporary Society. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, Philip. 2011. “Chinese: Maternal Grandmothers, Outside Women.” FamilyInequality.com, Retrieved February 13, 2012 (http://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2011/11/16/chinese-maternal-grandmothers-outside-women/).

Glezer, Helen. 1991. “Cohabitation.” Family Matters 30:24–27.

Glick, Paul. 1989. “The Family Life Cycle and Social Change.” Family Relations 38(2):123–129.

Griver, Simon. 2008. “One Wife Isn’t Enough … So They Take Two or Three.” The Jewish Chronicle Online, April 24. Retrieved February 13, 2012 (http://www.thejc.com/lifestyle/lifestyle-features/one-wife-isn’t-enough-so-they-take-two-or-three).

Haak, Wolfgang et al. 2008. “Ancient DNA Reveals Male Diffusion through the Neolithic Mediterranean Route.” Proceedings of the National Association of Sciences, November 17. Retrieved February 13, 2012 (http://www.pnas.org/content/105/47/18222).

Harrell, Stevan. 2001. “Mountain Patterns: The Survival of Nuosu Culture in China.” Journal of American Folklore 114:451.

Jayson, Sharon. 2010. “What Does a ‘Family’ Look Like Nowadays?” USA Today, November 25. Retrieved February 13, 2012 (http://www.usatoday.com/yourlife/sex-relationships/marriage/2010-11-18-pew18_ST_N.htm).

Joseph, Suad, and Afsaneh Najmabadi. 2003. “Kinship and State: Southeast Asia, East Asia, Australia and the Pacific.” Pp. 351–355 in Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law, and Politics. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers.

Lambert, Bernd. 2009. “Ambilineal Descent Groups in the Northern Gilbert Islands.” American Anthropologist 68(3):641–664.

Lee, Richard. 2009. The American Patriot’s Bible: The Word of God and the Shaping of America. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Mails, Thomas E. 1996. The Cherokee People: The Story of the Cherokees from Earliest Origins to Contemporary Times. New York: Marlowe & Co.

Murdock, George P. 1967. Ethnographic Atlas: A Summary. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Murphy, Patrick, and William Staples. 1979. “A Modernized Family Life Cycle.” Journal of Consumer Research 6(1):12–22.

Museum of Broadcast Communications. 2010. “Family on Television.” Retrieved January 16, 2012.

O’Neal, Dennis. 2006. “Nature of Kinship.” Palomar College. Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://anthro.palomar.edu/kinship/kinship_2.htm).