Chapter 9: Vectors

Introduction to Vectors

Introduction

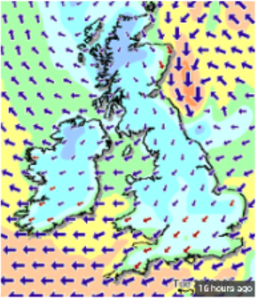

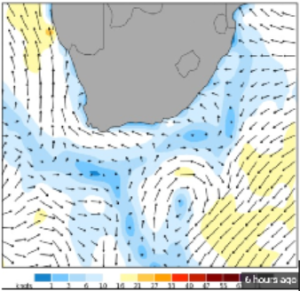

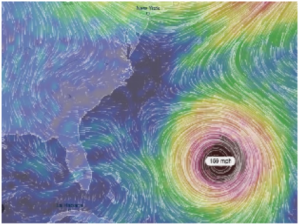

A vector is a mathematical tool that indicates both a direction and a size, or magnitude. Vectors are often represented visually as arrows. For example, we can use vectors to indicate the speed and direction of the wind. You may see weather maps like the ones below (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

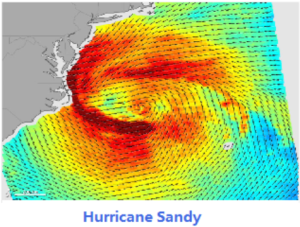

Usually the magnitude of the vector (the wind speed in this example) is shown by the length of the arrow, but sometimes a color key makes the map easier to read. Of particular interest are the winds produced by tropical storms or hurricanes and the forces that create the storm. Near the Earth’s surface, winds spiral toward the center of a hurricane. They rotate in a counterclockwise direction in the Northern Hemisphere and in a clockwise direction in the Southern Hemisphere.

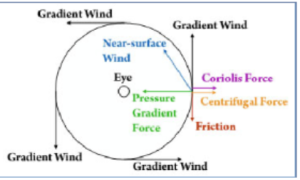

These rotating winds are called the hurricane’s primary circulation. A hurricane’s primary circulation involves four main forces (Figure 3):

- the pressure gradient force,

- the Coriolis force,

- the centrifugal force, and

- friction.

The center, or eye, of a hurricane contains the lowest atmospheric pressure, so the pressure gradient pulls air toward the center of the hurricane (Figure 4 and Figure 5). In the Northern Hemisphere, this air is deflected toward the right because of the Coriolis force, a result of the Earth’s own rotation. As the air turns to the right, the primary circulation around a hurricane begins to develop.

Hurricane researchers know that strong vertical wind shear is a major factor affecting potential hurricane development. Wind shear is the variation of the wind’s speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere. If there is too much wind, a storm has trouble developing into a cyclone. With little or no wind shear, the turning within the tropical system becomes vertically aligned, helping to keep it intact. Thus, the most favorable condition for tropical cyclone development is the absence of wind shear. Using simple mathematical models, researchers can estimate the degree to which the center of the storm becomes vertically tilted based on the cloudiness within the eyewall and the structure of the wind outside the eyewall. By modeling the development of storm tilt, a better understanding of a tropical cyclone’s behavior is gained in the presence and absence of wind shear. In particular, an El Niño weather system creates changes in the jet stream over the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in decreased wind shear in the Pacific and increased wind shear across much of the Atlantic basin (Figure 6), which suppresses hurricane activity. These model simulations show promise in understanding the processes driving the intensity of tropical cyclones.

Media Attributions

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 1 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 2 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 3 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 4 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 5 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter 9 Introduction Figure 6 © Trigonometry by Katherine Yoshiwara is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license