4 The Question of Freedom and the Age of Revolutions

Emergence of Modern Nationalism

As mentioned previously, by 1500, Europeans had not been consolidated into the type of extensive empires seen in Asia or Africa during roughly the same historical epoch. The European holdings of the Ottoman Empire were among the most integrated. While the Holy Roman Empire nominally still existed, Ferdinand II of Aragon died in 1516, and his grandson Charles V unified Castile and Aragon and initiated a monarchy that would become Spain. When the Protestant Reformation was launched in 1517, the Germanic lands of the empire split along religious lines: the east and north split into Protestant holdings, while the patchwork of the southern and western regions of the German states remained mostly Catholic. As Charles V was also a Habsburg, he also held Sardina, southern Italy, a partwork of states in the Alps, Bohemia (now southern Germany), and portions of states that are now Croatia, Austria, Hungary, and the Netherlands. Although the union represented the apogee of the Habsburg’s territorial holdings, most of these holdings were ruled more directly by local royalty, and upon his abdication in 1556, the Germanic holdings went to his brother, while the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands, Burgundy, and Italy went to the Spanish branch under Philip II, Charles V’s son.

Although the eastern branch of the Habsburgs continued to claim they were the “Holy Roman Empire,” they were really mostly a hodge-podge of Germanic, Uralic (Hungarian), Western Slavic (Czech and Polish), Eastern Romance (Romanian), Serbo-Croatian (Serbian and Croatian), and Ashkenazim (Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews) peoples, while some spoke Romance languages more closely related to French and Italian (Lombard, Venetian, Friulian, and Ladin, as well as pockets of French and Italian in the Alps). Their social and political unity was ever changing. The Holy Roman Empire hadn’t even included Rome itself in three centuries. Furthermore, during the 17th century, distinctions of religious practice, language, and local culture were increasingly played upon by lower-ranking royals, religious leaders, and merchant families in an effort to jockey for power. According to the Yunnan, China–born historian and political scientist Benedict Anderson, these preconditions, combined with the rise of print capitalism, mass vernacular literacy, and ever-increasing support for the abolishment of hereditary monarchy, inspired the rise of nationalism.

The transition to modern nation-states in Europe occurred, as it did in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, over the course of centuries, in fits and starts. While the United Provinces of the Netherlands revolted against the Iberian Habsburgs as early as 1581 and established an officially “Dutch Reformed” Protestant republic in 1588, it then became part of the “Sister Republics” of France during the epoch of the French Revolution, as a local Dutch revolution established the “Batavian Republic” in 1795. However, like France, the Batavian Republic would return to the status of a monarchy in 1806, just two years after Napoléon Bonaparte was proclaimed emperor of France. Nonetheless, from the 16th through the 19th century, a series of revolutions opposed absolute monarchies across the world. In the case of Europe, the process of state formation led to a consolidation of territory. In 1500, 80 million people were divided into 500 small states, principalities, and kingdoms. By about 1800, 150 million people were divided into just 30 empires, kingdoms, nations, and principalities. After the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), Switzerland gained independence and became a confederacy. During the French Revolution, they were transformed into the Helvetic Republic (f. 1798), and Switzerland arguably became the longest extant modern republic in Europe (save San Marino).

A third position between constitutional republics and hereditary monarchies also emerged in the 17th century. In 1649, the British monarchy agreed to a power-sharing agreement between an emerging class of wealthy but prominent and powerful merchants, who were often well connected to the Royal Navy. At the end of the Second English Civil War and after the trial and execution of the monarch Charles I, the Commonwealth of England (including England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland) briefly established a parliamentary republic. However, the House of Stuart was then restored in 1660. Yet the English Civil Wars set a precedent: they made clear that low-ranking nobles and a powerful mercantile elite could pose a threat to the monarchy. Gradually, the monarchy ceded them legislative powers in legislative bodies, like the House of Commons of Great Britain (1707–1801, the predecessor to the contemporary House of Commons of the United Kingdom).

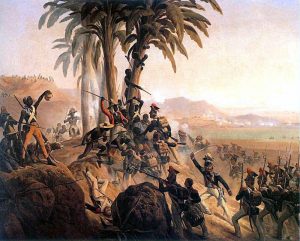

The most often cited revolution in world history textbooks is usually the French Revolution. Although the revolution was in part inspired by the victory of the French general Lafayette in the Americas against the British, in aid to the establishment of the nascent American republic that would become the United States, the proposed extension of democracy in France was far more radical. Furthermore, the impact was much more far reaching. It reached sister-republics in parts of Germany, Ireland, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland. While Napoleon restored the conception of a monarchy in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain, his interventions in the very same regions ended the institution of feudalism. Furthermore, the most ignored Atlantic revolution, the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), resulted in the first extant new nation where chattel slavery was entirely illegal. Additionally inspired by previous uprisings of enslaved peoples in the Caribbean, the Haitian Revolution inspired a wave of uprisings and revolutions led by enslaved people in Jamaica, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent, Grenada, Curacao Venezuela, Barbados, Guyana, the British Virgin Islands, Cuba, the Danish West Indies, Brazil, and Puerto Rico, all between 1795 and 1848.

Did you know?

The constitution of the Republic of Vermont (1777–1791) had previously banned the enslavement of adults (but not children). By provision of the constitution of the Vermont Republic, any enslavement was automatically ended upon the 18th birthday of someone ascribed female gender and upon the 21st birthday of someone ascribed male gender.

European Colonization and the Question of American Freedom

While modern nationalism is thought to have centered on the question of freedom, it is also notable that many of the questions raised, the style of debate, and the questions of property ownership—all of which were germane to the American, Haitian, and French Revolutions—were also certainly inspired by French- and English-language accounts of the Haudenosaunee (also known as “Iroquois”) Confederacy of the First Nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca). The Confederacy of First Nations was probably gradually formed between the 15th and 17th centuries. After 1722, the Tuscarora nation was added to the confederacy, and they became the “Six Nations.” A similar related northern group of First Nations became the Huron-Wendat Nations, also in the 17th century. However, the destruction of these First Nations is a long story that began virtually simultaneously with their first encounters with Europeans.

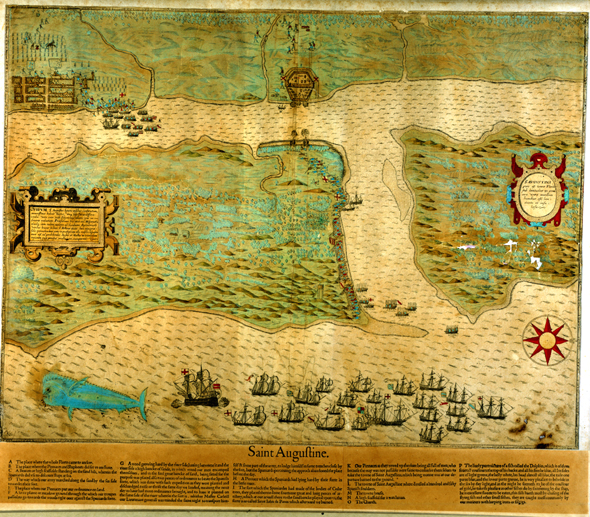

The Spanish established the first permanent European settlement on the North American coast in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. The French followed two decades later, building a fort in 1604 at Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia and establishing Quebec on the St. Lawrence River in 1608. The English had tried settling people on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, in 1588, but the colony had mysteriously disappeared by the time resupply ships returned to the area a few years later. The settlement may have been overrun by local indigenous peoples, but it is also possible that the abandoned colonists went to live with the natives when their food ran out and when help failed to arrive from England. Throughout the early history of English settlement in North America, colonial authorities regularly tried to hush up reports of poor English colonists choosing to live with the Native Americans. The English published frightening tales of captivity and redemption, although in reality, poor people, especially women, were often better treated in indigenous First Nations than in the English colonies or even in European society writ large.

After losing both their people and their entire capital investment at Roanoke, the English waited nearly 20 years before they tried settling the Chesapeake Bay region again in 1607. The Virginia Company, a joint stock venture chartered by King James I in 1606, sent expeditions to explore the coast of North America between the Spanish and French settlements, one of which established Jamestown forty miles inland on the James River as the first permanent English town in North America. In 1620, a shipload of persecuted—but rather extremist—Puritans we know as the “Pilgrims” fled England and the control of the Anglican Church, landing at Cape Cod. Ten years later, another group of Puritans received a royal charter to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony in Boston.

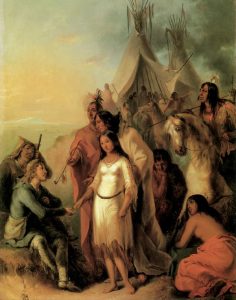

British colonists in North America focused on establishing family farms for raising crops and pasturing animals like cattle and sheep and growing cash crops like tobacco in the warmer climate of the South. By contrast, French efforts on the continent centered on trade with members of Native American First Nations for beaver pelts, since the growing season was much shorter in the region between the St. Lawrence River and Hudson Bay. Many French voyageurs married native women, creating the mixed-ethnic community known as métis today.

However, the alliance with the Native Americans did not change the outcome of the Seven Years’ War for France in 1763, as we will see in a bit. The French still lost all their North American territory to the British and Spanish (Napoleon later got the Louisiana Territory back, then almost immediately sold it to Thomas Jefferson).

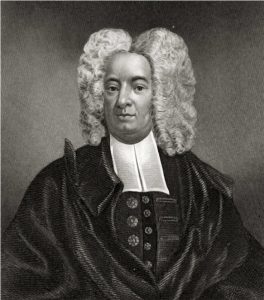

The diseases of the Columbian exchange spread more slowly in places where indigenous population density was comparatively lower, such as along the Atlantic coast of North America. But once again, it worked to the advantage of Europeans. Native populations in the coastal northeast were devastated by an epidemic that raged from 1617 to 1619 and killed 95 percent of the Abenaki people and over 90 percent of the Massachusett tribe. This emptying of the land was often seen by English settlers like the Pilgrims and the Puritans as a gift of divine providence. Puritan leader John Winthrop wrote about the favor God had shown to the colonists by killing the natives, and minister Cotton Mather wrote, “The Indians of these parts had newly…been visited with such a prodigious Pestilence; as carried away not a Tenth, but Nine Parts of Ten (yea, ’tis said Nineteen of Twenty) among them…So that the Woods were almost cleared of those pernicious Creatures, to make Room for better Growth” (Magnalia Christi Americana, 1702). English colonists were quick to take advantage of what they perceived as empty village sites, open farmland, and social chaos among the natives caused throughout the region by the ongoing Columbian exchange.

Although many individual settlers probably tried to deal fairly with their indigenous neighbors, the differences between European and native ideas of ownership and the rapid growth of the colonies made conflict virtually inevitable. Natives regularly moved to new locations as the seasons changed. They gardened in shifting fields. Colonists built houses and permanent villages and fenced their fields. But although they claimed complete ownership of the parcels they occupied, the colonists let their cattle and pigs run loose over the countryside. Since the natives were not protecting their lands in ways the colonists recognized, with fences, the Euro-Americans believed (or at least argued) indigenous Americans had no concept of land ownership. The colonists were unaware that native practices had been created for a world without domestic livestock, instead relying on a concept similar to previous European conceptions of “the commons.”

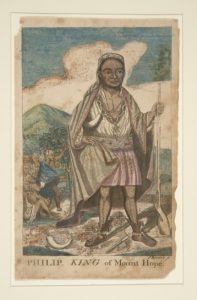

Often, when Native Americans treated European livestock like wildlife and shot a wandering cow, or when they killed pigs eating their unfenced crops, the colonists demanded compensation for the destruction of their property. And of course, more European colonizers arrived every year. The Powhatan Wars in Virginia (1610–46), the Pequot War in Connecticut (1637), the Dutch-Indian War in the Hudson Valley (1643), and the Beaver Wars (1650) all ended badly for the natives. Even King Philip’s War (1675), which is remembered as a disastrous, nearly successful uprising by Massasoit’s son Metacomet, who had finally decided enough was enough, resulted in five times as many native deaths as English. By the conclusion of the worldwide Seven Years’ War between the French and British Empires (known as the French and Indian War in North America) in 1763, northeastern First Nations were no longer considered a threat to European colonies, in no small part because local leaders of said First Nations did not find anything particular to be gained from the European colonies.

Questions for Discussion

- How did English settlement differ from Spanish or French colonialism?

- How did the Columbian exchange affect English settlement in North America?

- Why did English settlers believe God had intervened on their behalf?

- How did differences in land use lead to conflict between natives and colonists?

Comparative Colonization: The Spanish, the British, the Land, the Natives

The contrasts between Spanish and British colonization in the Americas are stark and help explain subsequent social and economic development in the hemisphere. The differences are especially visible in four areas: who the settlers were, how they were governed, how they worked the land, and the nature of their relationship with the indigenous peoples.

As described in the previous chapter, the Spanish had just completed an 800-year “Reconquest” of Iberia from Muslim rule in 1492, when Columbus first sailed west. Spain applied the same model of Iberian conquest and colonization to the Americas, granting conquered land with all of its inhabitants to the encomenderos, who were selected for their proven loyalty to king and empire, and to the Catholic Church. Soldiers and clergy were also pledged to crown and church, as well as the administrators, artisans, and other settlers who arrived in Spanish America with their families. The Portuguese in Brazil followed the same rule.

The British, however, used their colonies in North America as havens for religious dissenters, as a safety valve to reduce the numbers of the poor in England, and as dumping grounds for other troublemakers. As mentioned above, Massachusetts was settled by Puritans who had rejected the Church of England. Ironically, these seekers of religious freedom were so strict and dogmatic that anyone who disagreed even slightly was unwelcome in their new “city upon a hill.” Advocates of further reform soon left and settled Connecticut and Rhode Island, which were open to settlers of all religions—except Catholics, who instead settled in Maryland. Another dissenting religious group from England, the Quakers, colonized Pennsylvania, while Georgia was partly settled by petty criminals “transported” from Great Britain (Australia would serve this role in the late 18th and early 19th century). As a result, settlers of the Thirteen Colonies were less loyal to the British Crown than the Spanish settlers of Central and South America were to their monarch. Indeed, if the Spanish had followed the British policy of shipping their undesirables to the New World, “Latin” America might have become “Judeo-Islamic” America, a place where Jews and Muslims who had refused to convert to Catholicism were sent.

The Spanish and British also governed their colonies in very different ways. The Spanish Crown wanted to directly rule their American empire, appointing trusted men—the peninsulares—to serve as viceroys, judges, governors, and mayors, applying laws and regulations made by the Council of the Indies in Spain. British colonists already had a sense of self-government through their parliament, which checked the power of the king and controlled the treasury. Subsequently, in contrast to Spanish settlers, the British colonists set up legislatures, held town hall meetings, often appointed their own governors, and made many of their own laws rather than waiting for instructions from London.

This difference in representative government, however, does not mean that the Spanish colonists were completely deferential. They often applied the concept of “Obedezco, pero no cumplo” (I obey, but I do not comply) to regulations made by the Council of Indies that they believed did not consider local realities in the Americas. Also, especially in the 1700s, artisans and laborers initiated local riots and uprisings against unjust taxes or changes in religious governance, where the crowds shouted “Long live the king, and death to bad government!” until the wrongs were righted. Similar protests in the Thirteen Colonies would not occur until the 1770s.

Land arrangements were also very different between the British and the Spanish. Both empires had sugar and other plantations that depended on enslaved African labor (which we will examine below). However, for other crops (especially those for local consumption), the Spanish followed the tradition of the encomendero (and later, hacendero), in which a large landowner employed indigenous and mestizo workers, while the British settlers preferred the individual family farm. In the long run, this economic difference affected attitudes about entrepreneurship and ideas of personal liberty. The large landowners in Spanish America did not want to disrupt a social system that brought them wealth, while in the Thirteen Colonies, even the lowliest indentured servant who had worked without pay for seven years looked forward to gaining their own plot for themselves “out West.”

The fourth major difference between Spanish and British America involves relationships with the indigenous peoples. Basically, the Spanish had arrived and said, “This is our land, obey us,” while the British said, “This is our land, go somewhere else.” The Spanish Empire included the indigenous in their colonial project, partly because of the blood ties that connected many of the Spanish with their mestizo descendants. Mestizos and indigenous peoples were often protected or at least tolerated by Spanish authorities in their own settlements as long as they paid tribute and at least pretended to be Catholic. Just like their counterparts in North America, the indigenous peoples in Latin America also faced the problem of the Spanish allowing their pigs and cattle to destroy native plantings—but as Spanish colonial records reveal, the indigenous peoples brought this injustice to local Spanish judges, who often determined in favor of them, as opposed to Spaniards. Many locals felt that they were part of colonial society and confidently challenged Spanish landowners in court.

Still, the Spanish colonies were far from a utopia for the natives. They did not have complete control over their lives, and the “protection” offered by Catholic clergy required abandoning their own religion and many of their customs and practices. The Spanish did not want to physically eliminate the indigenous, but they did advocate a cultural genocide of sorts, which was never complete due to native resistance. But this was, in the long run, less successful than the destruction of native culture in North America because despite the Columbian exchange, there were more natives left. Native languages thrive in many parts of Central and South America, where they are preserved and spoken by millions, while the tribal tongues of North America struggle to stay relevant.

The social and economic differences between British and Spanish America clearly have consequences even today, some positive and others negative. The entrepreneurial spirit common in the United States has resulted in a less rigid class system than in Latin America, while the idea that the U.S. is a “white man’s country” (from which African Americans were also excluded) has led to systemic racism that is still an enormous problem, especially when compared to attitudes about race in most of Latin America, where mestizos and mulattos abound.

Questions for Discussion

- How did racial mixing make Spanish American society different from Anglo-American society?

Caribbean Islands and Sugar Cane

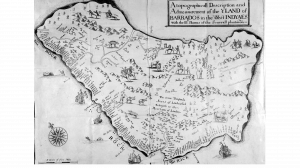

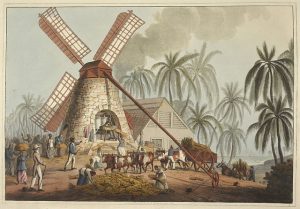

In spite of the beginning of British settlement in North America, Britain’s main focus in the 17th century was the Caribbean. We tend to forget this because this region did not join the North American revolution in 1776 and become part of the United States. But in the 1600s, sugar islands like Barbados and Jamaica were the most profitable British colonies. Like the Spanish, North American colonists in the New World expected and hoped to find not only a place to build a new society but also a place where they could get rich. Even religious idealists such as the Pilgrims looked forward to opportunities for wealth and social mobility that had not been available to them in England. And right from the start, European colonies in North America were commercial. In addition to fishing, growing tobacco, and trapping beaver, the North American colonies benefited from the booming sugar economy of the Caribbean.

Islands such as Barbados that had once been self-sufficient had begun by the mid-1600s to specialize in the profitable commodity at the expense of all other crops, so sugar planters looked to their neighbor colonies for food supplies and feed for draft animals. John Winthrop, the Puritan leader who helped establish Boston and who was governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony four times before 1650, sent his second son, Henry, to help establish Barbados in 1626. When Oliver Cromwell’s civil war halted the flow of commercial shipping between England and the ten-year-old Bay Colony in 1640, trade with the West Indies saved Boston’s economy. Governor Winthrop’s younger son, Samuel, joined the growing community of New England merchants in the Caribbean sugar islands in 1647.

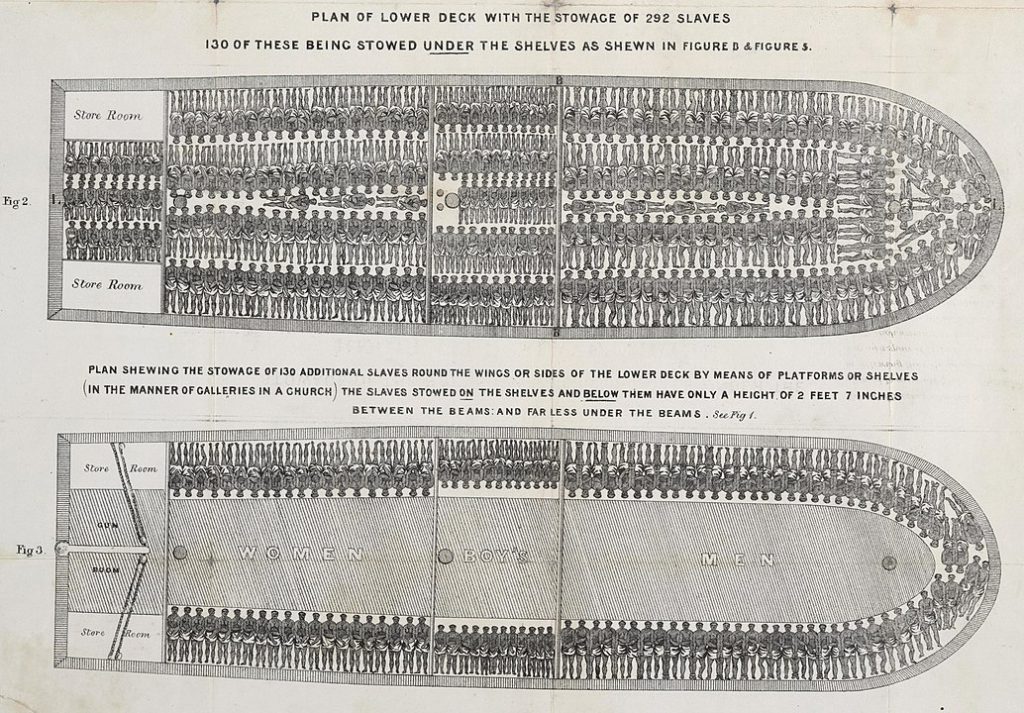

About 16 million Africans were captured and transported to European slaveholding colonies during the entire period of Atlantic slavery. Only 12 million arrived alive. A quarter of all enslaved people taken died on the voyage across the Atlantic. Additionally, another 11 to 14 million people were enslaved from Africa under the Islamic system of slavery. However, the latter number was spread over the course of 12 centuries; included enslaved people who lived in Muslim principalities, kingdoms, and empires in Africa; and also included many more opportunities for manumission when compared to the chattel system of the transatlantic slave trade. How might African societies had been different if the 16 million people captured and forced into the transatlantic slave trade remained on the continent? Recent studies have confirmed that the introduction of American crops—such as maize and manioc—led to massive population growth in Africa. However, the same studies have shown that the introduction of the new crops did not necessarily lead to increased economic growth or reduced conflict, as was previously thought. In fact, a recent study by two Canada-based scholars, Jevan Cherniwchan and Juan Moreno-Cruz, has argued that the introduction of maize may have led to increased conflict in African societies, as it did little more than increase the potential supply of enslaved people.

As European slave traders frequently established partnerships with African political elites, most enslaved peoples were captured at first by other Africans. While historian Walter Rodney identified regions of West Africa where slavery seemed to be entirely absent during the early days of European contact, by the late 18th to early 19th century, the Oyo (Yoruba, Nigeria) and Kong (Burkina Faso) empires; the kingdoms of Koya (Sierra Leone), Khasso (parts of Senegal and Mali), and Kaabu (Senegambia); the Fante and Ashanti confederacies (both in what is now Ghana); and the Imamates of Futa Jallon (Guinea) and Futa Toro (Senegal) all grew in part as a result of the sale of war captives to European slave traders. Most famously, the Amazon warriors of the Dahomey kingdom (Benin), called “Mino” in the local Fon language, emerged specifically in the context of the men of Dahomey facing high casualties in the brutal conflicts of the 18th and 19th centuries. The all-female Mino unit practiced the Vodun religion of the Fon peoples of Dahomey and retained a semi-sacred status. Yet they were also active participants in the military campaigns that fed the slave trade.

A few of the West African states that participated in the transatlantic slave trade were part of the global trend that began to question the structure of feudal societies in the 18th century. For instance, King Osei Kwadwo (1764–1777) of the Ashanti Confederacy abolished the previous system of appointing noble officials based on their birth. In its place, he instituted a meritocratic system of appointment based on merit. While King Osei Kwadwo retained the power of the head of the military (de facto commander in chief) in domestic matters, his power was checked by a council of state elders, similar to a senate. In principle, if the king overstepped his bounds, the elders could impeach him and demote him to the status of a commoner. Furthermore, a council of younger men was called the nmerante, which tended to democratize and liberalize the political processes of the Ashanti Confederacy. These structures of the Ashanti Confederacy would have been quite familiar to British peoples of the 18th century who lived in a monarchy, which was checked by the powers of the House of Lords and the House of Commons, if only they had learned the Twi language of the Ashanti.

Another form of West African revolution in the 18th century is typically known under the term “Fulani jihads.” These jihad were in fact a series of revolutions led by ethnic Fula people, the first of which was an attempt to overthrow Hausa Maguzawa hereditary rule in 1725 and establish the aforementioned Futa Jallon “Imamate.” By 1750, the Fula leadership established the Imamate of Sokoto, and by 1776, they established the Imamate of Futa Toro. These imamates were revolutionary in that to be an imam, one had to also be a scholar, and as such, the widespread promotion of literacy was central to their mission. Furthermore, they aimed to draw on religiously invoked understandings of equity among Africans to draw support into the cause of staving off European colonialism, often with direct conflict against invading European armies. Finally, when the revolutionary leader Usman dan Fodio defeated the nearby Hausa Kingdoms in the Fulani War in 1804, the very same year that the Republic of Haiti gained independence, he consolidated the Imamate of Sokoto in the form of a new caliphate, also called Sokoto.

Like the leadership of the Ashanti Confederacy, Osman dan Fodio also did away with hereditary titles, instead establishing a meritocratic system of appointing subordinate emir based on the ability of the individual to master Islamic studies of religion, law, and society. Furthermore, when the head of the caliphate died, the council of emir would gather together and appoint the new head of the caliphate. The practice represented a major democratic intervention into the previous system of hereditary rule. However, it is also of note that the Sokoto Caliphate was a massive empire, and the number of war captives created led to a dramatic increase of enslaved people in Fulani-controlled society, making the Sokoto Caliphate one of the major holders of enslaved people from West Africa in the early 19th century—second, of course, to the southern United States.

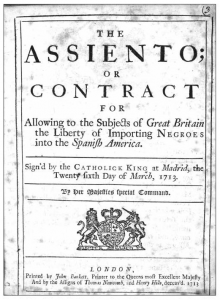

The massive growth of the slave trade in the Americas during the 18th and 19th centuries was directly tied to the growth of plantation-based economies. Historians have more recently begun to refer to this period of history, when plantation-based economies began to have a dramatic impact on the natural environment and human societies, as the “plantationocene.” The emergence of the plantationocene is precisely why there was an introduction of West Africans to the Caribbean to begin with. We might recall the material covered in previous chapters: the horrible treatment of indigenous labor led Bartolome de las Casas to argue that the importation of African labor should be used as an alternative. However, for Spain—under the Treaty of Tordesillas—access to African ports had been ceded to Portugal. Consequentially, a monopoly contract over the supply of West African enslaved peoples was established, called the Asiento. The Asiento was initially granted to France, but the Spanish Crown shifted the contract to the British South Sea Company for a 30-year term beginning in 1714.

The company set up slave distribution “factories” at Cartagena (Colombia), Veracruz (Mexico), Portobello (Panama), La Guaira (Venezuela), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Havana, and Santiago de Cuba, as well as its own colonies of Barbados and Jamaica. In 1720, a speculative investment “bubble” burst, throwing the British economy into crisis. The South Sea Company survived the burst of its bubble, mostly due to revenues from selling slaves, and its slave sales peaked in 1725, five years after the financial crisis.

Conditions were so harsh on sugar plantations that slaves generally died about three years after their arrival. Plantation owners could have changed their practices, but the reduced profits would have exceeded the replacement costs of the slaves, so planters chose to work slaves to death quickly and buy more. The economic value of local “increase” produced by enslaved women was recognized in the 18th century in the North American colonies where people like Thomas Jefferson wrote about the money that could be made on these natural replacements. Additionally, raising tobacco and other crops was less harsh than cultivating sugar cane, creating better conditions for survival. Britain and the U.S. ended the slave trade in 1807 and 1808, but the act of slavery continued in the U.S. Enslaved people in mid-Atlantic states, where tobacco was being replaced with mechanized wheat farming, were “sold down the river” to the increasingly important cotton plantations in the Deep South, creating a major profit opportunity for white Virginians.

Slaves often resisted their captors. Sometimes they ran away and formed independent communities in remote hinterlands called maroon colonies. Many of these maroon colonies became stable societies—populated by formerly enslaved people who had escaped their bonds and the descendants of indigenous peoples who had run away from the colonists’ earlier attempts to enslave them—and some even lasted into the twentieth century in Central and South America.

Other times, the enslaved peoples organized outright militarized uprisings and revolutions—often unsuccessfully, but not always. A quite partial list of some notable uprisings follows, although there were more than a dozen more by the early 19th century alone:

- 1526 San Miguel de Gualdape (Spanish Florida, Victorious)

- 1570 Gaspar Yanga‘s Revolt (Veracruz, New Spain, Victorious)

- 1712 New York Slave Revolt (British Province of New York, Suppressed)

- 1730 First Maroon War (British Jamaica, Victorious)

- 1733 St. John Slave Revolt (Danish Saint John, Suppressed)

- 1739 Stono Rebellion (British Province of South Carolina, Suppressed)

- 1741 New York Conspiracy (Province of New York, Suppressed)

- 1760 Tacky’s War (British Jamaica, Suppressed)

- 1787 Abaco Slave Revolt (British Bahamas, Suppressed)

- 1791 Mina Conspiracy (Louisiana, New Spain, Suppressed)

- 1795 Pointe Coupée Conspiracy (Louisiana, New Spain, Suppressed)

- 1791–1804 Haitian Revolution (French Saint-Domingue, Victorious)

- 1835 Male Revolt (Brazil, Suppressed)

Questions for Discussion

- Why would plantation owners choose to work slaves to death rather than treat them better?

- Why don’t we read more about slave revolts in most of history?

The New World and the Enlightenment: Independence of the United States

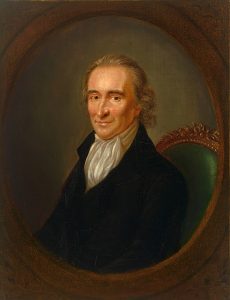

The Enlightenment encouraged a gradual shift from an understanding of political sovereignty as a gift of God (the divine right of kings as expressed by absolute monarchs like Louis XIV) to ideas of popular sovereignty and government by consent of the governed or through a “social contract” between rulers and people. The Enlightenment blossomed when people discovered new knowledge through both exploration and science and began throwing off what they considered the superstitions of an earlier age, including the “divine right” of kings. Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau began reimagining the relationship between individuals and society, while popular writers like Thomas Paine began translating these ideas into pamphlets like Common Sense and into books like The Rights of Man and The Age of Reason that were read not only by other philosophers but also by hundreds of thousands of regular literate people.

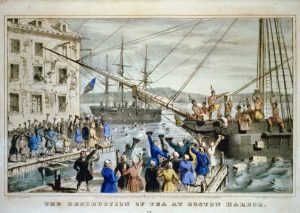

Some of the first places these Enlightenment political ideas were tested were Britain’s thirteen North American colonies. The Seven Years’ War (1756–63) had been an expensive drain on Britain’s treasury, and Parliament believed the American colonists ought to pay their fair share of the cost of their defense. Britain instituted a number of taxes including the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Act (1767), and the Tea Act (1773). Boycotts and protests by the colonists soon began, including the famous Boston Tea Party in 1773, during which enraged patriots boarded a British cargo ship and dumped tea from India into Boston Harbor rather than pay the hated new tax.

Although the colonists found these taxes oppressive and obnoxious, to a great extent, they were luxury taxes or excises on trade rather than direct taxes on personal income. Still, imposing new taxes on the colonists was a miscalculation by Parliament, because the merchants and the wealthy most affected by the taxes had the means and the motivation to organize a resistance movement.

American colonists also objected to the Quartering Act (1765), which forced them to provide housing and food for British troops. Again, this may have seemed fair to the legislators back in London, who had sent an army to defend the colonies against the French and Native Americans in the recently concluded war. But it was a big expense for the Americans and was an issue that cut across class boundaries more than the luxury taxes and unified opposition. Imagine being a poor farmer in New England and having a red coat from some random region of England living with you and eating your food.

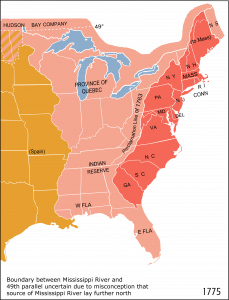

Another major cause of American resentment against the British after the Seven Years’ War was the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which established a western boundary to the colonies roughly along the ridgeline of the Appalachian Mountains. The support of Native Americans from the trans-Appalachian region had been critically important to the British war effort in North America. Tribes such as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) were powerful allies, and their leaders complained about the increasing numbers of settlers leaving the coastal colonies to make farms in places like Upstate New York, western Pennsylvania, and the Ohio River Valley. The British created a reserve for Native Americans beyond the Appalachians, including western Virginia and Pennsylvania west of Pittsburgh, which had been a French fort captured in the war. This angered both colonists who looked west for new lands to settle and land speculators who had planned on getting rich by buying and selling the western territory.

In addition to the famous “all men are created equal” and “consent of the governed” parts of the colonists’ Declaration of Independence, the 1776 document included a laundry list of complaints against the British Crown, including the charge that the king had “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” The founders understood that independence would mean taking land from the indigenous First Nations of Native Americans, whom they termed “Savages.” Although the declaration echoed the Enlightenment ideals of contractual government and representation, at the time, these ideals only applied to white male landowners.

Many Native Americans sided with Britain in the American Revolution because they saw a British victory as their only chance to prevent the colonists from overrunning them. Many slaves also ran away to join British forces, especially after they were offered immediate emancipation by Lord Dunmore. Many fought their former owners in Dunmore’s “Ethiopian Regiment” or secretly sided with the British against colonial slaveholders.

Nor did the declaration speak for all the white colonists. New York City was occupied by the British until 1783, well after the end of the fighting, and the city was a haven for supporters of the British side. Historians have estimated the number of loyalists at 15–20% of the total colonial population, or about 400,000 people. Most of these loyalists stayed and became U.S. citizens after the war, but about 70,000 left for other parts of the British Empire. Many of those in the north went to Canada and settled New Brunswick, while southerners went to Florida, which had remained loyal under British rule, or to the British islands in the Caribbean.

After the Revolution, poor Americans were often left wondering what they had fought for. Taxes were high, and farmers couldn’t pay them because the “Continental” currency printed by the rebel government to pay the troops was worthless. Western Massachusetts farmers who felt the new government in Boston did not represent them revolted in 1786 in Shays’ Rebellion, which was put down by government troops. This fight and others forced leaders of the Confederate states to reconsider how a federal government should be organized, and they called a Constitutional Convention to meet in Philadelphia, with the thirteen states sending representatives.

The United States Constitution that formed the new government began with the words “We the People.” It acknowledged the Enlightenment concept that political power comes from the consent of the governed. The final document was influenced by the framers’ studies of earlier republics and by negotiations over various state constitutions that had favored the idea of three branches of government—the legislative, executive, and judicial—along with a system of checks and balances that made no one branch superior to the others. For instance, the president could veto laws passed by Congress, while Congress could, with a two-thirds majority, override the veto. And the Supreme Court could interpret a law as being unconstitutional, checking both the president and Congress.

In spite of these checks and balances, when the Constitutional Convention sent the newly drafted Constitution to all the states for ratification, many New England towns either rejected the document outright or provisionally approved it with modifications they sent back to the authorities. In most cases, their provisional approvals were marked as simple yes votes, and the carefully worked-out modifications were “filed.” But dissatisfaction with the original Constitution was so strong, in spite of the series of promotional articles published about it that have become known as the Federalist Papers, that the convention was forced to write the first 10 amendments (the Bill of Rights) and issue them at the same time. Without the Bill of Rights, the Constitution would be a much different document.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the British government consider the taxes they imposed on the colonists reasonable?

- Why did Native Americans and Blacks side with the British during the Revolution?

- What prompted the writing of the Bill of Rights?

The French and Haitian Revolutions

Debt problems stemming from the Seven Years’ War and French support for the independence of the United States forced King Louis XVI to call the Estates-General in 1789 in order to raise revenue. The Estates-General had not been called since 1614, and its meeting was immediately seen as an opportunity to create a new parliamentary monarchy.

The three “estates” (commoners, nobility, and clergy) each had one vote in the Estates-General, even though the commoners represented the vast bulk of the population. The delegation of commoners was dominated by educated merchants and large landowners who hoped to establish a British-style parliament as a check on the king’s power. With the support of a few deputies of the clergy and nobility, the commoners replaced the Estates-General with the National Assembly, in which all deputies had equal voting rights regardless of their social background.

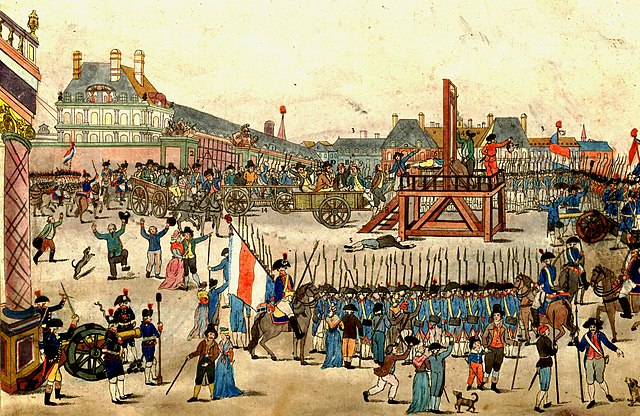

Meanwhile, the people of Paris formed militia groups to defend the National Assembly from royalist attacks. On July 14, 1789, these militias dramatically took over the Bastille, a royal prison that held political dissidents (July 14 is now the French national holiday). In August, the National Assembly passed a Declaration of the Rights of Man that claimed “Natural Law” as the basis for equal rights for all and called for liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. The text was drafted in part by the Marquis de Lafayette, a French veteran of the U.S. War of Independence, and Thomas Jefferson, who was U.S. ambassador to France at the time. Like the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, the assembly declared that the “nation” was sovereign, rather than the king, and asserted the rights of freedom of speech, the press, religion, and assembly. It also abolished cruel and unusual punishments, so engineers devised a new instrument, the guillotine, to carry out death sentences more humanely.

However, the French Revolution differed from the American in that (outside of the colony of Haiti) it was not a colonial independence movement but a rejection of an existing monarchy by the people of France. There was a much greater degree of participation by poor people in France in this process, and the social changes attempted by the new government were much more significant than simply replacing a British ruling class with an American one, as the revolution had done in the new United States. The power vacuum created by the elimination of the prior government structure resulted in the rise of a radical Jacobin Party led by Maximilien Robespierre, who proclaimed a “Reign of Terror” in 1793. In an effort to eliminate counterrevolutionaries, the Jacobins imprisoned 300,000 people and executed 40,000 using the guillotine, including King Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette. Another 200,000 soldiers and civilians died in a civil war in the Vendée region of France, where armies of the Republic battled the chouans, peasants who remained loyal to the king and the Catholic Church.

Among the prisoners who just barely escaped with their lives by dint of fate was Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense. The American had been welcomed as an honorary citizen of the new French Republic and had even been given a seat in their new legislative assembly. Although he had defended the French Revolution against British criticism in his book The Rights of Man, Paine was imprisoned for objecting to the execution of the French king and queen. Paine was scheduled for execution but was passed over in a lucky oversight. Others were not so fortunate. One of the victims was the French feminist and abolitionist Olympe de Gouges, who had advocated for equal rights for men and women in the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1791). Although she had initially supported the revolution, she criticized the execution of Louis XVI and was closely associated with the Girondists, a faction that increasingly opposed the more radical Montagnard faction. After the Reign of Terror targeted the nobility, the Girondists were the second targets. The violence only ended in 1794, when Robespierre himself was deposed and executed.

The French Revolution had important repercussions in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, known today as Haiti. The colony was the leading exporter of sugar and coffee in the world, but its wealth was predicated on the brutal exploitation of African slaves, who represented 90 percent of the colony’s population (the remaining 10 percent were free people of color and free whites). The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, particularly article 1, which stated that “all men are created and remain free and equal in rights,” resonated with slaves and free people of color, who had much to complain about the slavery and racial discrimination underpinning the plantation system.

Political infighting within the white population in France and Haiti gave the population of color an opportunity to revolt. In 1790, a mixed-race planter named Vincent Ogé demanded equal rights for free people of color. When he failed to secure these rights in Paris, he led an uprising in Haiti but was arrested and brutally executed.

The slave majority was next to rise. In August 1791, 50,000 slaves revolted in the northern part of Haiti, killed 300 planters, and burned hundreds of sugar and coffee plantations. Slave revolts had been frequent in the 18th century Caribbean given the brutal treatment of African slaves, but the revolt in Haiti was the only one to survive a counterattack by colonial authorities. Within a year, the revolt involved the colony’s 500,000 slaves, making it the largest slave revolt in the history of the Americas (by comparison, the largest uprising in U.S. history, near New Orleans, involved only 500 slaves).

After the death of Vincent Ogé, the French revolutionary government granted political rights to free people of color in March 1792, but it resisted abolishing slavery outright and sent 6,000 soldiers to the island to put down the revolt. The context, however, was not favorable for France. Rebel slaves far outnumbered French soldiers. A general war broke out in Europe in 1792–1793 as conservative monarchies tried to put down the French Revolution, which tied down French forces there; in 1793, Britain and Spain also sent forces to Haiti in an attempt to seize a valuable plantation colony.

Two of the officials the French sent to put down the slave revolt, Étienne Polverel and Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, were Jacobin abolitionists who were hesitant about their mission. Concluding that they could not prevail with the forces sent from France, they abolished slavery in the colony in 1793. They hoped to convince the rebel slaves, who had already gained their freedom through revolt, to join the French army and help expel the British and Spanish invasion forces. Three deputies from Haiti traveled to France, where in 1794, they convinced the French parliament to recognize the abolition of slavery, not just in Haiti but throughout the French colonial empire.

The French Revolution fell short of instituting gender equality, but it implemented some radical changes: France became a Republic, the Catholic Church lost its privileged status, Jews and Protestants could worship openly, commoners and nobles became equal under the law, and, initially at least, slavery was abolished. The revolution also standardized the size of French provinces and established the metric system.

At the end of the Reign of Terror, the revolutionary government was led by a five-member governing committee, commonly called “The Directory.” While this Directory sought to export the revolution and continue the abolishment of hereditary monarchies through the establishment of sister-republics, it also cracked down on the Jacobins and stepped back from the intense revolutionary fervor of the early revolution. Political retrenchment provided an opening for an ambitious opportunist named Napoleon Bonaparte, who as a general of the French Army had defended the new French Republic against the neighboring monarchies. Returning from an Egyptian campaign in 1799, Napoleon overthrew the Directory and, like Julius Caesar, established a 3-man consul-style government. He quickly became the sole leader and crowned himself emperor in 1804.

Questions for Discussion

- How was the French Revolution different from the American?

One advantage Napoleon had in establishing his empire, in addition to his effective use of the French Army, was that he was able to reinstate many members of the old nobility who had been discredited or even imprisoned during the revolution. He even allowed aristocrats to reclaim some of the property the revolutionaries had taken from them. Napoleon also introduced a new civil code in 1804 that completely revamped the French legal system and is still in use today. The code replaced France’s old feudal legal system and was influential throughout the world as nations developed modern legal systems (it is the basis for Louisiana’s civil code, for example).

In a series of wars, Napoleon extended French control to much of Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Duchy of Warsaw and built strong alliances with Austria and Prussia. At its height, the French Empire ruled over 70 million subjects.

Though he maintained some of the changes brought by the revolution, such as legal equality for all men, Napoleon backtracked in some other areas. He reestablished a monarchical system (with him on the throne) and negotiated a concordat with the Vatican that restored the Catholic Church’s privileged place in France. In 1802, he also sent armies to various French Caribbean colonies to restore the prerevolutionary racial order.

By then, Haiti was ruled by Toussaint Louverture, a former slave who had become a general in the French Army and then governor of the colony during the revolution. Napoleon’s army captured Louverture and transported him to a French prison where he died in 1803, but the revolution continued under his lieutenant Jean-Jacques Dessalines. By relying on innovative guerrilla tactics, and with the help of an outbreak of yellow fever, the former slaves defeated the French expeditionary force and declared the independence of Haiti in 1804. This was the second colony to gain independence in the Americas, after the United States, and the first and only successful slave revolt in world history.

Napoleon was able to restore slavery in some other colonies, such as Guadeloupe. He also refused to recognize the independence of Haiti, which France continued to claim as its own until Haiti paid a 150 million francs indemnity in 1825. (As part of a worldwide campaign for reparations for slavery and the slave trade, the Haitian government demanded in 2003 the repayment of that indemnity.)

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, was president when Haiti declared its independence but refused to officially recognize the new state. The opposition of slavery-supporting southern politicians blocked recognition of Haiti by the U.S. government until the Civil War.

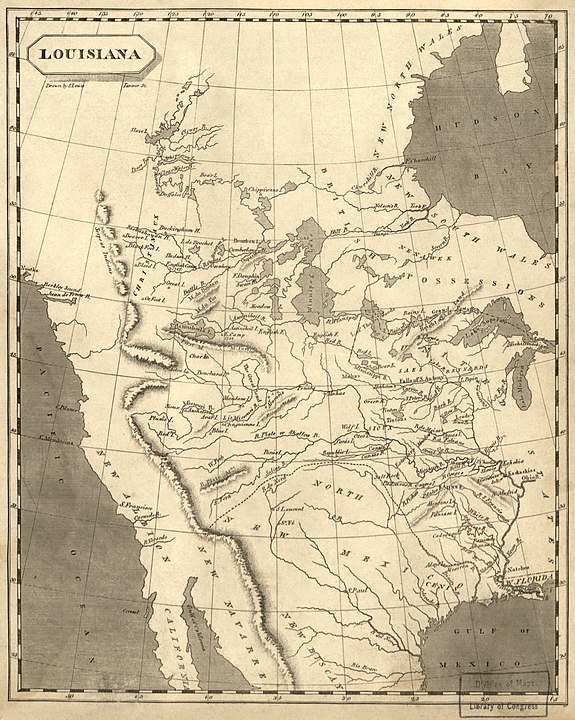

Another momentous act of Napoleon was his sale of 828,000 square miles of North America to the U.S. in 1803. The failed expedition to Haiti and the prospect of a new war with Britain convinced Napoleon to take $50 million francs (about $11 million today) for the territory it had only just regained from Spain. The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the U.S. As shown in this 1804 map, people living on the East Coast were aware of how big North America was between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, even if they were a bit hazy about what lay between the Rockies and the Pacific.

Questions for Discussion

- Compare the abolishment of slavery in Haiti and in the U.S., Brazil, and British colonies. Was the abolishment a peaceful or violent process in each case? When did slaves get their freedom? Did slaves get financial compensation…or planters?

In a final example of bad judgment, Napoleon invaded Russia and attempted to occupy Moscow in September 1812. Russia’s fast-moving Cossack cavalry executed a scorched-earth retreat before the advancing French Army, so Napoleon’s forces arrived in Moscow hungry, only to find that the city’s quarter-million people had abandoned their homes and taken everything they could carry. The French burned the city (possibly by accident) and began a long retreat in early October at the beginning of what turned out to be a brutal winter. The Russian cavalry repeatedly cut the French supply lines, and of an original force of over 600,000 men, only about 100,000 made it back to France alive. Napoleon was able to build the army back up again, but this crushing debacle proved to the world that he wasn’t the military genius many had believed him to be.

Napoleon’s enemies invaded France in 1814, forced him to abdicate, and exiled him to Elba, a small island near his boyhood home of Corsica. Napoleon escaped the Mediterranean island and regained power briefly in 1815 before being defeated at Waterloo and exiled to St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died six years later at the age of 51. Louis XVI had died during the French Revolution, as had his son and heir, so two of his brothers reigned as Bourbon kings when Napoleon was exiled and monarchy was restored.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was Napoleon willing to sell Louisiana to Thomas Jefferson?

- What prevented the U.S. government from recognizing Haiti?

Independence of Latin America

Napoleon’s conquest of Europe inadvertently created the conditions for additional revolutions and the creation of new nations in the Americas. As described in the last chapter, Spanish American society was based on a small aristocracy of ethnic Spanish peninsulares (people born on the Iberian Peninsula) and criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies) ruling large populations of mestizo (mixed) populations, indigenous peoples, and enslaved peoples. Like the leaders of the American Revolution, many of these colonial aristocrats felt that the priorities of their rulers in Spain did not match their own. Napoleon’s removal of the hereditary king and installation of his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne in 1807 removed the last shred of doubt. Soon after Joseph Bonaparte took the throne, representative juntas were established in Caracas, Santiago, Buenos Aires, and Bogotá to rule in the name of the deposed Spanish king.

In 1810, a creole priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla began Mexico’s revolutionary movement by giving a speech known as the Grito de Dolores, or simply El Grito, “the Cry.” Hidalgo raised an army of 100,000 men, largely of landless peasants anxious for social reform, but they were defeated in January 1811 by a professional army of about 6,000 Spanish troops. Hidalgo was convicted of treason against Spain and executed. Another (this time mestizo) priest named José Maria Morelos took over the insurrection and convened a congress in 1813 that wrote a constitution for Mexico called the Decreto Constitucional para la Libertad de la América Mexicana, which declared Mexico’s independence. Unlike later independence movements in South America, Mexico’s demanded not just political but also social change.

In 1815, Morelos was also captured and executed. His lieutenant Vicente Guerrero continued the war for independence. Guerrero would be elected president of Mexico in 1829 and would be Mexico’s first black president. But it was a long way to 1829.

King Ferdinand VII was the Spanish monarch who had been forced to abdicate in 1808 in favor of Joseph Bonaparte. He regained the throne in 1813 but quickly became known as “el Rey Felón,” the criminal king. Ferdinand rejected the liberal 1812 constitution that had been adopted by Spain’s rebel government during his absence. Historians have described him as “the basest king in Spanish history. Cowardly, selfish, grasping, suspicious, and vengeful, [he] seemed almost incapable of any perception of the commonwealth. He thought only in terms of his power and security and was unmoved by the enormous sacrifices of Spanish people to retain their independence and preserve his throne.” Latin American juntas and the Mexican rebels decided he did not deserve their allegiance and began fighting for their independence from Spain.

The royal government sent a general named Agustín de Iturbide against Guerrero’s forces in Mexico, but Guerrero beat Iturbide on the battlefield and then convinced him to join the revolution. In 1821, the two allied under the Plan de Iguala, or the “Plan of the Three Guarantees,” which proclaimed Mexico’s independence and declared that “all inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.” When Iturbide declared himself emperor of Mexico, Guerrero and his supporters rebelled, and although Iturbide defeated them in the field, he resigned when Antonio López de Santa Anna also rebelled, and went into exile. Both Iturbide and Guerrero ended up being executed in their turns.

In 1811, Venezuela and Paraguay both declared their independence from Spain. In 1816, Argentina declared its independence, followed quickly by Chile and Gran Colombia. King Pedro of Portugal, whose father had fled to Brazil in 1807 to avoid being deposed by Napoleon, declared Brazil a constitutional empire under his rule in 1822. In 1824, the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar, who had led the liberation of Gran Colombia, conclusively defeated the Spanish armies at Junín and Sucre, and Peru gained its independence. A year later, the eastern portion of the old viceroyalty of Peru became a separate country named after the liberator Bolívar: Bolivia.

Gran Colombia was a republic that includes territory now part of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil. Bolívar was elected president of Gran Colombia from 1819 to 1830. He hoped Latin America would follow the example of the United States and create a federal union of all the newly independent nations—or at least a common economic market. He convened a Congress of the Americas in the summer of 1826, inviting all the nations of Latin America and also the United States. The U.S. president, John Quincy Adams, didn’t have a very high opinion of Latin Americans, but he was an opponent of slavery, and all of the new Spanish American republics had immediately outlawed the slave trade and had either abolished slavery or initiated its gradual disappearance through manumission. The independent Brazilian Empire, on the other hand, did not formally end enslavement of people of color until 1888, the last nation in the Americas to do so. Adams had also been instrumental in promulgating the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, establishing the Western Hemisphere as a region under the protection of the U.S. and warning European nations, especially Great Britain, to limit their activities in the Americas.

Britain, however, did attend the Congress of the Americas as an observer and managed to gain several important trade deals as a result. But blocked once again by the senators of the slave-holding southern states, the U.S. government dragged its feet. Although the U.S. ultimately decided to send a delegation, it arrived only after the congress had ended. Bolívar was unable to establish the Pan-American commonwealth he had dreamed of or even hold Gran Colombia together. He resigned the presidency in the spring of 1830, and the republic dissolved into the three separate nations of Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. Bolívar died of tuberculosis at age 47 later that year.

Questions for Discussion

- What was the significance of Mexico’s 1821 Plan de Iguala?

- How do you think history would have been different if Bolívar had been successful in his plans for a United States of South America?

Primary Source #1: U.S. Declaration of Independence

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.—Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Primary Source Supplement #2: The Haitian Declaration of Independence, 1804

The Commander in Chief to the People of Haiti

Citizens:

It is not enough to have expelled the barbarians who have bloodied our land for two centuries; it is not enough to have restrained those ever-evolving factions that one after another mocked the specter of liberty that France dangled before you. We must, with one last act of national authority, forever assure the empire of liberty in the country of our birth; we must take any hope of re-enslaving us away from the inhuman government that for so long kept us in the most humiliating torpor. In the end we must live independent or die.

Independence or death… let these sacred words unite us and be the signal of battle and of our reunion.

Citizens, my countrymen, on this solemn day I have brought together those courageous soldiers who, as liberty lay dying, spilled their blood to save it; these generals who have guided your efforts against tyranny have not yet done enough for your happiness; the French name still haunts our land.

Everything revives the memories of the cruelties of this barbarous people: our laws, our habits, our towns, everything still carries the stamp of the French. Indeed! There are still French in our island, and you believe yourself free and independent of that Republic which, it is true, has fought all the nations, but which has never defeated those who wanted to be free.

What! Victims of our [own] credulity and indulgence for 14 years; defeated not by French armies, but by the pathetic eloquence of their agents’ proclamations; when will we tire of breathing the air that they breathe? What do we have in common with this nation of executioners? The difference between its cruelty and our patient moderation, its color and ours the great seas that separate us, our avenging climate, all tell us plainly that they are not our brothers, that they never will be, and that if they find refuge among us, they will plot again to trouble and divide us.

Native citizens, men, women, girls, and children, let your gaze extend on all parts of this island: look there for your spouses, your husbands, your brothers, your sisters. Indeed! Look there for your children, your suckling infants, what have they become?… I shudder to say it … the prey of these vultures.

Instead of these dear victims, your alarmed gaze will see only their assassins, these tigers still dripping with their blood, whose terrible presence indicts your lack of feeling and your guilty slowness in avenging them. What are you waiting for before appeasing their spirits? Remember that you had wanted your remains to rest next to those of your fathers, after you defeated tyranny; will you descend into their tombs without having avenged them? No! Their bones would reject yours.

And you, precious men, intrepid generals, who, without concern for your own pain, have revived liberty by shedding all your blood, know that you have done nothing if you do not give the nations a terrible, but just example of the vengeance that must be wrought by a people proud to have recovered its liberty and jealous to maintain it let us frighten all those who would dare try to take it from us again; let us begin with the French. Let them tremble when they approach our coast, if not from the memory of those cruelties they perpetrated here, then from the terrible resolution that we will have made to put to death anyone born French whose profane foot soils the land of liberty.

We have dared to be free, let us be thus by ourselves and for ourselves. Let us imitate the grown child: his own weight breaks the boundary that has become an obstacle to him. What people fought for us? What people wanted to gather the fruits of our labor? And what dishonorable absurdity to conquer in order to be enslaved. Enslaved?… Let us leave this description for the French; they have conquered but are no longer free.

Let us walk down another path; let us imitate those people who, extending their concern into the future, and dreading to leave an example of cowardice for posterity, preferred to be exterminated rather than lose their place as one of the world’s free peoples.

Let us ensure, however, that a missionary spirit does not destroy our work; let us allow our neighbors to breathe in peace; may they live quietly under the laws that they have made for themselves, and let us not, as revolutionary firebrands, declare ourselves the lawgivers of the Caribbean, nor let our glory consist in troubling the peace of the neighboring islands. Unlike that which we inhabit, theirs has not been drenched in the innocent blood of its inhabitants; they have no vengeance to claim from the authority that protects them.

Fortunate to have never known the ideals that have destroyed us, they can only have good wishes for our prosperity.

Peace to our neighbors; but let this be our cry: “Anathama to the French name! Eternal hatred of France!”

Natives of Haiti! My happy fate was to be one day the sentinel who would watch over the idol to which you sacrifice; I have watched, sometimes fighting alone, and if I have been so fortunate as to return to your hands the sacred trust you confided to me, know that it is now your task to preserve it. In fighting for your liberty, I was working for my own happiness. Before consolidating it with laws that will guarantee your free individuality, your leaders, who I have assembled here, and I, owe you the final proof of our devotion.

Generals and you, leaders, collected here close to me for the good of our land, the day has come, the day which must make our glory, our independence, eternal.

If there could exist among us a lukewarm heart, let him distance himself and tremble to take the oath which must unite us. Let us vow to ourselves, to posterity, to the entire universe, to forever renounce France, and to die rather than live under its domination; to fight until our last breath for the independence of our country.

And you, a people so long without good fortune, witness to the oath we take, remember that I counted on your constancy and courage when I threw myself into the career of liberty to fight the despotism and tyranny you had struggled against for 14 years. Remember that I sacrificed everything to rally to your defense; family, children, fortune, and now I am rich only with your liberty; my name has become a horror to all those who want slavery. Despots and tyrants curse the day that I was born. If ever you refused or grumbled while receiving those laws that the spirit guarding your fate dictates to me for your own good, you would deserve the fate of an ungrateful people. But I reject that awful idea; you will sustain the liberty that you cherish and support the leader who commands you. Therefore vow before me to live free and independent, and to prefer death to anything that will try to place you back in chains. Swear, finally, to pursue forever the traitors and enemies of your independence.

Done at the headquarters of Gonaives, the first day of January 1804, the first year of independence.

A translation of the document by Laurent Dubois and John Garrigus as published in “Slave Revolution in the Caribbean 1789–1804: A Brief History with Documents.”

Primary Source Supplement #3: MAXIMILIAN ROBESPIERRE, THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF TERROR, FEBRUARY 5, 1794

Citizen-representatives of the people.

Some time ago we set forth the principles of our foreign policy; today we come to expound the principles of our internal policy.

After having proceeded haphazardly for a long time, swept along by the movement of opposing factions, the representatives of the French people have finally demonstrated a character and a government. A sudden change in the nation’s fortune announced to Europe the regeneration that had been effected in the national representation. But up to the very moment when I am speaking, it must be agreed that we have been guided, amid such stormy circumstances, by the love of good and by the awareness of our country’s needs rather than by an exact theory and by precise rules of conduct, which we did not have even leisure enough to lay out.

It is time to mark clearly the goal of the revolution, and the end we want to reach; it is time for us to take account both of the obstacles that still keep us from it, and of the means we ought to adopt to attain it: a simple and important idea which seems never to have been noticed. . . .

For ourselves, we come today to make the world privy to your political secrets, so that all our country’s friends can rally to the voice of reason and the public interest; so that the French nation and its representatives will be respected in all the countries of the world where the knowledge of their real principles can penetrate; so that the intriguers who seek always to replace other intriguers will be judged by sure and easy rules.

We must take far-sighted precautions to return the destiny of liberty into the hands of the truth, which is eternal, rather than into those of men, who are transitory, so that if the government forgets the interests of the people, or if it lapses into the hands of the corrupt individuals, according to the natural course of things, the light of recognized principles will illuminate their treachery, and so that every new faction will discover death in the mere thought of crime. . .

What is the goal toward which we are heading? The peaceful enjoyment of liberty and equality; the reign of that eternal justice whose laws have been inscribed, not in marble and stone, but in the hearts of all men, even in that of the slave who forgets them and in that of the tyrant who denies them.