1 The World at 1500

This chapter provides a snapshot of the major regions of the world at the year 1500. From South and Central Asia to Europe, Africa, and the Americas, each region was relatively well developed. The chapter highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each region to lay the ground for subsequent chapters.

The world in the year 1500 was at one of its most unique points in history. Each region was relatively stable and secure with access to resources, and each had sufficient creativity to use them. Rather than start our textbook with one region, a “snapshot” view of all regions of the world can show how each were politically, economically, and culturally diverse yet also had important points of intersection. Each had geographical advantages and disadvantages, most were rural societies but experienced growing class differences and pressures to urbanize, all were patriarchal, and all had to contend with outside political forces particularly in terms of trade, policy, and migration.

The regional approach provides a starting place from which to trace what will become very different pathways for the future of each region. There is an undeniable wealth gap that begins to emerge over the course of the 16th through the 20th centuries, with the majority of the world’s wealth concentrated especially in Western Europe and—albeit to a lesser extent—North America and Northeast Asia, especially Japan. Previous perspectives on this history, such as those of geographer Jared Diamond in the pop-history Guns, Germs and Steel (1997), have focused on the dual advantages of geography and technology which allowed Western Europe to “advance.” Some others were very critical of Jared Diamond’s work. Fellow geographer James Blaut referred to him as an example of a “Eurocentrist.” Some authors believed other factors were at play. In The Great Divergence (2001), Kenneth Pomeranz argued that the supply of coal in Europe was a critical factor in emerging differences between the productive capacities of 19th-century Western Europe and central China. Increasingly, social scientists and historians looked toward environmental factors as a way to understand world history, especially after John R. McNeil published Something New Under the Sun (2001), arguing that something fundamental had changed, worldwide, during the course of the 19th and 20th centuries: the relationship between humans and the environment. In his latest The Origins of the Modern World (4th edition, 2019), McNeil provides a critique of Jared Diamond’s original “rise of the west” research question and a reframing around thinking about the world in terms of its regions as well as the relationship between humans and their environs.

Our text will trace from the late classical era through the “Anthropocene,” or the era in which humans have had a distinct impact on the Earth’s environment to the point of marking a new geological time. Taking this a step further, the term denotes a new cultural and political understanding of people’s relationship with the planet. It is important for us to keep in mind the simple fact that the populations of Asia, Europe, and Africa were quite similar in the year 1500. However, while Asia and South Asia (India) accounted for greater shares of the world population than they do today, Europe accounted for less. Furthermore, the population of Asia was nearly twice that of Africa and Europe combined, with another 125 million in China, and some 110 million in South Asia. Indeed, most of the world’s wealth was located in East, Southeast, and South Asia. In the Americas, the Inca Empire was thriving in the Andean region under ruler Wayna Qhapaq. Indeed, across the Americas, there was a massive network of nations, federations, and empires of some 60 million people in 1500 CE, being roughly comparable to the population of Europe and slightly less than that of Africa. As we shall see, the dispersal of wealth across these regions was about to dramatically change, as was the relationship between humans and the environment across them.

Asia

Imperial China

In 1356, an ambitious 28-year-old General Zhu Yuanzhang conquered the southern Chinese capital of Nanjing, making it his base for the next 12 years. Then he turned his troops northward and removed the Mongol-Yuan dynasty from their capital of Dadu (now the “northern capital” of Beijing). The Mongols retreated to Mongolia, and Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared himself the first emperor of the Ming dynasty and ruled for 30 years. He tried to erase Mongol influence and return the empire to its Han Chinese roots. In 1402, Zhu Di overthrew his nephew and named himself the Yongle Emperor of Perpetual Happiness. It was during the reign of the Yongle Emperor that China made many technological, infrastructural, and territorial advances.

The Yongle Emperor ruled through an extensive network of court eunuchs who formed his palace guard and secret police. He repaired and reopened China’s Grand Canal, the 1,104-mile waterway that linked the Yellow and Yangxi Rivers and enabled the new capital to receive rice shipments from the south. Between 1406 and 1420, he also directed 100,000 artisans and 1 million laborers in building the Forbidden City in Beijing as a permanent imperial residence.

One of Zhu Di’s most trusted subordinates was the Muslim admiral Zheng He (1371–1433). The new Yongle Emperor appointed Zheng He as admiral of his fleet and sent him on seven expeditions between 1405 and 1430. Zheng He’s fleet was interested not in establishing colonies but in exacting tribute and opening trade relationships throughout South and Southeast Asia. The fleet traded for ivory, spices, ointments, exotic woods, giraffes, zebras, and ostriches. In some locations, such as the Champa kingdom of Vijaya, Zheng He’s fleet was welcomed, as locals had long held good relations with Chinese dynasties. However, in others, Zheng He’s forces were less welcome, and he even demanded tribute from the rulers of kingdoms like Palembang on the island of Sumatra—which had been plagued by the pirate Chen Zuyi—and the Kingdom of Kotte on Sri Lanka. Often, when local leaders seemed unwilling to submit, Zheng He seized them and brought them to Beijing, where they could be convinced of the overwhelming power of the Chinese Empire. Among the places Zheng visited were Vijaya (Champa, now Vietnam), Brunei, Ayutthaya (Thailand), Java, Chittagong (Bangladesh), the west coast of India, Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, Jedda on the Red Sea, and Mogadishu and Mombasa on the east coast of Africa. Zheng He’s seven expeditions often extracted trade deals from many neighboring kingdoms, and Yongle trusted him so completely that he sent Zheng He blank scrolls with his imperial seal on them to use in whatever way he chose.

After a final voyage in 1433, expeditions were halted, and the fleet was retired and ultimately burned. Ending China’s navy was one of the major changes made by Zhu Di’s descendants. The burning of the Chinese fleet left a power vacuum in the South China Sea. Japanese, Chinese, and local coastal pirates, many of whom had been lingering throughout the reign of the Yongle Emperor, now became more active. Shortly after Zhu Di and Zheng He’s deaths, China was challenged from the north again. Sixteen years after Zheng He’s final expedition, Zhu Di’s great-grandson, the sixth Ming emperor, was captured and held hostage by Mongol raiders in 1449.

Questions for Discussion

- What do you think was the most significant element of Zheng He’s seafaring missions?

- With such a commanding technological lead, why did China turn away from the outside world and suspend exploration?

- What might the world look like now if the Chinese Empire had continued along the lines begun by Zheng He?

The alarmed Chinese turned their attention to their border defenses and rebuilt the crumbling Long Walls into a 1,550-mile-long fortification with hundreds of guard towers. The Long Walls had existed since the beginning of the Chinese Empire but had failed to hold off Mongol invaders. Under the Ming, the Great Wall was improved and extended, especially around the capital of Beijing and the agricultural heartland in the Liaodong Province north of the Korean Peninsula. The Chinese population rose from 100 million in 1500 to 160 million in 1600. However, the threat of a Manchu land invasion from the north was taken very seriously, to the detriment of authorizing further naval expeditions. China’s turning away from the ocean was a momentous decision in world history, opening the door for Japanese, South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Europeans to dominate the Indian Ocean and Pacific trade networks at different points of history.

As the generations passed, Ming emperors and their courts became increasingly isolated in the Forbidden City the Yongle Emperor had built. Some were important rulers, others were just uninterested in ruling. Similar to other new imperial dynasties, the Ming dynasty began by concentrating political power in the emperor and in the civil servants chosen through the Confucian examination process. The ruling class grew even more influential, and power shifted as the new elite protected their lands and possessions from taxation. Corrupt officials siphoned funds designated for public works into their own pockets, and infrastructure such as dams and dikes crumbled. Eventually, irrigation systems failed and peasants died in widespread famines.

At the same time, Manchuria was being unified under strong military leaders who had adopted Chinese ways and who even employed Confucian administrators. Furthermore, mass rebellions broke out across Ming China in the 1620s and 1630s. Some of the officers then defected to the Manchu-Jurchen forces. In 1644, rebellion broke out close to Beijing, and the Manchu offered military aid to the Ming, while the rebels also offered military aid to the Ming as well. Fearing the political repercussions, the Ming Chongzhen emperor committed suicide. However, before his death, he had sent a message north of the Great Wall to a Ming general in Manchuria. While the rebels claimed to be establishing a new dynasty and keeping northern invaders out, the Ming general appealed to the Manchu-Jurchen commanders to help him restore the shattered Ming dynasty. Once the Manchu armies were south of the Great Wall, they began to consolidate northern China, even as a series of Ming loyalists retreated to the south. The Manchu army, led by Prince Rui (Dorgon), took control of Beijing and declared the end of the Ming Empire and the beginning of a new dynasty, the Qing, meaning pure.

We will return later to the history of China, the Qing dynasty, and what came after. For now, it is important to note that China was a powerhouse in the world in 1500, when our survey of modern world history begins. In 1500, the Chinese population was growing rapidly, the Ming Empire had a standing army of over a million soldiers, and the Chinese navy of Zheng He had recently projected the empire’s power throughout Asia and the Indian Ocean world.

In 1500, the Chinese economy produced the economic value of one-quarter of the world’s goods and services (today what we might call gross domestic product, or GDP), followed by India, which produced nearly another quarter. In comparison, the fourteen kingdoms and empires of Western Europe produced just about half of Ming China’s economic output, or only one-eighth of the global total production. The largest European economy, in Italy, produced only about one-sixth of China’s output.

The Ming Empire’s population in 1500 was about 125 million. The next largest empires were Southern India’s Vijayanagara Empire (16 million), followed by the Inca Empire of South America (12 million), the Ottoman Empire (11 million), the Spanish Empire (about 8.5 million), and the Ashikaga Shogunate of Japan (8 million). As the Chinese had turned to internal affairs, so were other people strengthening their own cultural customs and traditions, in particular in Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan.

Questions for Discussion

- Discuss the symbolism of the Great Wall in Chinese culture.

- Does the size, complexity, and age of the Chinese Empire alter your understanding of the early modern world?

Southeast Asia

For more than two millennia, human societies in Southeast Asia have blended influences from East Asia (especially China) and South Asia (especially India) with indigenous cultural creations. From the 2nd century CE through the 16th century, a mixture of Hinduism and Buddhism from South Asia, often called “Hindu-Buddhism,” characterized Southeast Asian civilizations, such as those of Champa (Vietnam), the Empire of Angkor (Cambodia), Majapahit (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore), Ayutthaya (Thailand), and Pagan (Myanmar). Then, from the 11th through the 17th century, Islam also became increasingly popular in the region. Consequentially, Indonesia is the world’s most populous Muslim country. Attracted by luxury goods, including spices, early Chinese traders recorded the peoples of the region. They even travelled up the Mekong River Delta region (now southern Vietnam, Cambodia, and southern Laos), which they described as “Land Chenla” and “Water Chenla” in very early historical records. When Chenla’s power decreased, a new empire grew in its wake: Angkor.

Angkor is both typically the name of the empire and the capital-center of a precolonial civilization that we might associate with Cambodia. However, the Angkorian Empire at its peak stretched across large swathes of Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand as well as all of modern-day Cambodia. Further, the official name for the center of Angkor was actually not Angkor but Yashodharapura. The inscriptions of Angkor, carved into stone monuments, combined the religious language of Sanskrit with the local Khmer (Cambodian) language. The dynasties of the Angkorian Empire trace their lineage to Jayavarman II, who rose to the throne in 802 CE and established a whole series of new centers. Gradually the empire grew. Yet “Angkor” itself—as in Yashodharapura—was not built until the end of the 9th century. In the 12th century, the most powerful monarch, Jayavarman VII, built the famous Bayon at Angkor and displayed a strong devotion to Mahayana Buddhism. Indeed, almost all other Khmer kings up to this point displayed a strong devotion to Hinduism. Although Hinduism popularly blended with Mahayana Buddhism at Angkorean temples, just two Khmer monarchs were Mahayana Buddhists. Instead, by the 13th century, monks from Sri Lanka introduced the Theravada school of Buddhism to Angkor. This school of Buddhism also spread to the Mekong Delta (now in Vietnam, but formally associated with Angkor and later Khmer kingdoms), Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar.

In the 15th century, Southeast Asia was in transition. To begin with, Angkor had been wracked by a long series of internal conflicts of succession and massive wars with neighbors. Recent research has shown some form of climate shift caused the trading profits of the area to gradually decline. The current hypothesis is that elites then began to move to the more profitable centers of the Mekong Delta. Gradually, the massive roadways, temples, and cities that had stretched from Thailand and Laos through the heartland of Cambodia began to fall into disrepair. The rise of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in the Chao Phraya River Valley (now Thailand) also brought a new challenge to Angkor. Then, in 1431/2, Ayutthaya suddenly sacked Yashodharapura and the surrounding area. Although local Khmer remained in the vicinity, the remaining Khmer elite then abandoned the capital, along with surrounding area, and fled to a series of new capitals southeast of the Tonlé Sap, along the Mekong River. The 15th- through 19th-century Kingdom of Cambodia grew increasingly diverse, as Khmer people mixed with Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese, Cham, and Malay peoples. Cambodia even had a king that converted to Islam in the middle of the 17th century. However, most of the population remained Theravada Buddhist. Pressure from Siamese (Thai) and Vietnamese kingdoms grew from the 17th through the 19th century. By the 19th century, much of the eastern areas of what is now Cambodia were controlled by the Vietnamese and western areas, including where Angkor remained, were under Siamese (Thai) control. To maintain some form of independence, the Cambodian court established various trade-tribute relations with both, along with accepting trade tribute from peoples periphery to both the Vietnamese and Cambodian kingdoms, such as the Jarai “King of Water” and “King of Fire.”

Between the 2nd century and the 15th century, most of what is now Vietnam was controlled by the civilization of Champa—a collection of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms, sometimes unified and sometimes fighting with one another, that rose and fell over time. Far north, in the Red River Delta, a Vietnamese kingdom also grew during this time, although they were conquered by the expansion of the Chinese Han dynasty, leading to centuries of Chinese domination. After gaining independence in the 10th century, a new kingdom called Dai Co Viet gave birth to the rise of Vietnamese power in Southeast Asia. Dai Co Viet then changed its name several times, although it was most known as “Dai Viet” from the 11th through the 19th centuries, at which point the name “Viet Nam” was introduced by the Nguyen dynasty. Dai Viet’s society was shaped by a combination of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism—much like East Asian cultures found in Japan, the Korean Peninsula, and China.

Dai Viet warred frequently with Champa, and a Champa army crushed the Vietnamese army several times in the 14th century. Then, in the early 15th century, the Ming dynasty from China conquered Dai Viet and made the Vietnamese kingdom subordinate to the Chinese Empire once again for a period of twenty years. Upon regaining independence in 1427, Le Loi rebuilt the Vietnamese army and established the Le dynasty. During the later part of the 15th century, the Le dynasty conquered much of central Champa, expanding Vietnamese lands. However, from the 16th through the 18th century, there were a series of civil conflicts, including the Tay Son Rebellion. Yet, a new house of lords had emerged in the 1670s, and through their work repressing the Tay Son Rebellion, they would grow to become the most powerful political family in Vietnam: the House of Nguyen. From the 17th through the 19th century, the Vietnamese would conquer and annex the remaining Champa kingdoms. Also in the 19th century, the House of Nguyen proclaimed themselves the rulers of an empire, and they expanded control into parts of Laos, Cambodia, the former Cambodian lands of Mekong Delta, and the Central Highlands—even into parts of what is now Cambodia today.

Among the great empires of classical and late classical Southeast Asia, the island empire of Majapahit is certainly among the most important to know about. A predominantly Mahayana Buddhist Melayu Kingdom had ruled the Island of Sumatra and the Malay peninsula in the 7th century and again in the 12th to 14th century. Additionally, the Tantric Hindu-Buddhist Shailendra dynasty emerged on the island of Java in the 8th century and expanded to Sumatra in the 9th century to 11th century. However, their power was disrupted by internal conflict, and smaller Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms controlled much of Island Southeast Asia. In the 13th century, the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan sent 1,000 ships to invade Java. However, they were manipulated amidst local power conflicts, and the Javanese forced the fleet to retreat. In the wake of the Mongol retreat, Raden Wijaya proclaimed a new capital and kingdom in 1293 CE: Majapahit. Majapahit then expanded into an empire, controlling 98 tributaries from Sumatra to New Guinea. At its apogee, Majapahit controlled territories associated with most of Indonesia, Singapore, most of Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand, East Timor, and the Sulu Archipelago of the southwestern Philippines. The riches of Majapahit include the prize possession of the Maluku Islands: the Spice Islands.

From the 11th through the 17th centuries, the culture of Island Southeast Asia became increasingly Muslim. The Wali Songo (9 Saints) of Java were 15th- through 16th-century individuals especially credited with the conversion of the Javanese courts, including Sunan Ampel, who was a Muslim from the aforementioned Champa and would die in Demak, Java. Indeed, parts of Majapahit had begun to proclaim independence, and the Sultanate of Demak broke off from Majapahit in 1475 CE. By 1527 CE, even the central regions and the old capital of Majapahit had been defeated by the Sultanate of Demak. Besides Demak, the most important historical sultanate was probably the Sultanate of Melaka, which controlled the Straits of Malacca—and thus the taxation of the trade route connecting the entire Indian Ocean to the South and East China Seas—from the 15th through the early 16th centuries. Indeed, 16th-century Melaka was so rich that the Portuguese apothecary, travel-writer, and imperialist Tomé Pires proclaimed, “Whoever is lord of Malacca shall have his hands on the throat of Venice.” These words, or course, were written after the 1511 CE Portuguese conquest of Melaka, so we might view them with a grain of salt. Nonetheless, Melaka was undoubtedly a cosmopolitan place, with over 80 languages spoken there.

Southeast Asia circa 1500 was a region in transition. Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms on the mainland and in Island Southeast Asia declined in power. On the mainland, Theravada Buddhism grew in popularity in what is now Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia. In Island Southeast Asia, Tantric Hindu-Buddhism gave way to Islam. In Vietnam, a local blend of Southeast Asian Vietnamese and East Asian Chinese culture grew more dominant. Additionally, European imperialists, first Portuguese, then Spanish and Dutch, were in the process of expanding modicums of local power. Nonetheless, the control of the precious spice trade remained predominantly in the hands of the so-called Malay Sultanates. The Sultanate of Ternate (1257–1914) was a major regional power and a top producer of cloves from the 15th through 17th century, with thanks to their control of the Maluku Islands (the Spice Islands). The black pepper industry also boomed in Southeast Asia during the early modern period, with thanks to the Malay Sultanates, and the promises of Southeast Asian trade even attracted ships from Japan.

Japan

Shogun was the military dictator of Japan from 1185 to 1868 (with exceptions). In most of this period, the shoguns were the de facto rulers of the empire, although nominally, they were appointed by the emperor as a ceremonial formality. The shogun held almost absolute power over territories through military means. A shogun’s office or administration is the shogunate, known in Japanese as the bakufu. The shogun’s officials were collectively the bakufu and carried out the actual duties of administration, while the imperial court retained only nominal authority. In this context, the office of the shogun had a status equivalent to that of a viceroy or governor-general, but in reality, shoguns dictated orders to everyone, including the reigning emperor.

During the second half of the 16th century, Japan gradually reunified under two powerful warlords, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In the hope of founding a new dynasty, Hideyoshi asked his most trusted subordinates to pledge loyalty to his infant son Toyotomi Hideyori. Despite this, almost immediately after Hideyoshi’s death (1598), war broke out between Hideyori’s allies and those loyal to Tokugawa Ieyasu, a feudal lord (daimyō) and former ally of Hideyoshi. Tokugawa Ieyasu won a decisive victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, and although it took him three more years to consolidate his position of power over the Toyotomi clan and the daimyōs, Sekigahara is widely considered to be the unofficial beginning of the Tokugawa bakufu.

In 1603, Emperor Go-Yōzei declared Tokugawa Ieyasu shogun. Ieyasu abdicated two years later to groom his son as the second shogun of what became a long dynasty. Despite laws imposing tighter controls on the daimyōs, the latter continued to maintain a significant degree of autonomy in their domains. The central government of the shogunate in Edo, which quickly became the most populous city in the world, took counsel from a group of senior advisors known as rōjū and employed the samurai as bureaucrats. The emperor in Kyoto was funded lavishly by the government but had no political power.

The period of the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, known as the Edo period, brought 250 years of stability to Japan. The political system evolved into what historians call bakuhan, a combination of the terms bakufu and han (domains). In the bakuhan, the shogun had national authority and the daimyōs had regional authority. This represented a new unity in the feudal structure, which featured an increasingly large bureaucracy to administer the mixture of centralized and decentralized authorities.

A code of laws was established to regulate the daimyō houses. The code encompassed private conduct, marriage, dress, types of weapons, and numbers of troops allowed. It required the feudal lords to reside in Edo every other year, prohibited the construction of oceangoing ships, proscribed Christianity, restricted castles to one per domain (han), and stipulated that bakufu regulations were the national law. The Tokugawa shogunate went to great lengths to suppress social unrest and imposed harsh penalties on anyone they thought might be a threat. Christianity, which was seen as a potential threat, was gradually restricted until it was completely outlawed. To prevent further foreign ideas from sowing dissent, the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, implemented the sakoku (closed country) isolationist policy, under which Japanese people were not allowed to travel abroad, return from overseas, or build oceangoing vessels. The only Europeans allowed on Japanese soil were the Dutch, who were granted a single trading post on the island of Dejima. China and Korea were the only other countries permitted to trade, and many foreign books were banned from import.

The Islamic Empires of South and Central Asia

While China was the first, oldest, and largest Asian empire, the Islamic empires also set the scene for the early modern period, and their histories helped shape the world today. These were the Mughal Empire in India, the Safavid Empire in Persia (Iran), and the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. Each of these empires built their expanses of land by ruling from the top and initially benefited from the stable and strong but largely agricultural economies. Furthermore, Muslims had a strong impact on the history of the Ming Empire, the defining early modern empire of China.

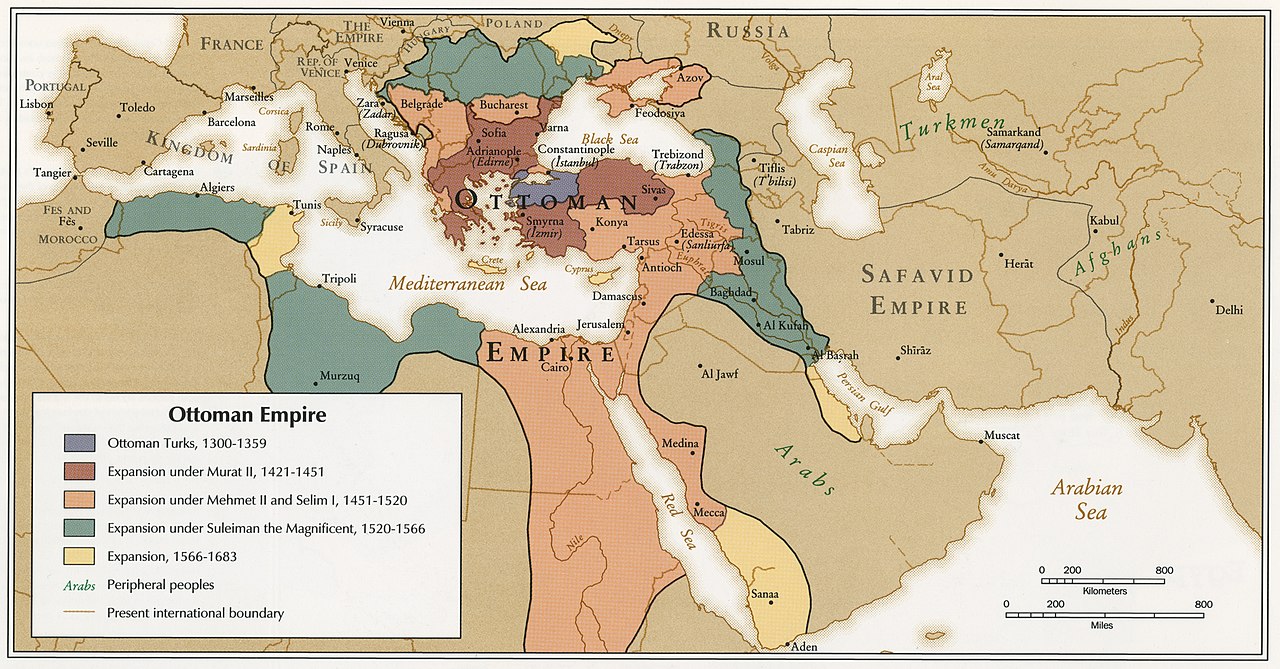

The Ottomans were a Muslim dynasty that rose on the borders of the Byzantine Empire in the 1300s and became a world power when Sultan Mehmed II (called Mehmed the Conqueror) overwhelmed the defenders of Constantinople in 1453.

Constantinople had been the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) since the emperor Constantine had moved his government there in 330 CE. The city was strategically important because it controlled the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits that connected the Mediterranean Sea with the Black Sea. This made it the gateway between Europe and Asia. Mehmed took the city as his new capital, and later it was renamed Istanbul. As was usual in Muslim practice, the sultan allowed Christians and Jews to continue living in Istanbul and granted the Eastern Orthodox Church autonomy as long as they accepted Ottoman authority. Istanbul quickly became the largest Eurasian city outside China. Mehmed II then led Ottoman armies further into the European lands of Moldova and Albania but was turned back at Venice in 1481.

Ottoman Empire to 1683

Suleiman the Magnificent was the longest-reigning sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1520 until his death in 1566. At the helm of an expanding empire, Suleiman personally instituted major judicial changes relating to society, education, taxation, and criminal law. His reforms harmonized the relationship between the two forms of Ottoman law: sultanic (kanun) and religious (the shari’a, or Islamic law). He was a distinguished poet and goldsmith. He also became a great patron of culture, overseeing the “Golden Age” of the Ottoman Empire in its artistic, literary, and architectural development.

Suleiman had at least three wives, which is a demonstration of his wealth, since in accordance with religious law, he would have to prove he had the resources to care for additional spouses. Breaking with Ottoman tradition, Suleiman married Hürrem Sultan, an Orthodox Christian of Ruthenian origin who converted to Islam. Their son, Selim II, succeeded Suleiman following his death in 1566 after 46 years of rule. Suleiman’s other potential heirs, Mehmed and Mustafa, had died; Mehmed had died in 1543 from smallpox, and Mustafa had been strangled to death in 1553 at Suleiman’s order. His other son, Bayezid, was executed in 1561 after a rebellion, along with Bayezid’s four sons, again on the sultan’s orders. As problems built internally, Suleiman’s reforms struggled and his progressive supporters dwindled.

Suleiman’s reign was a watershed in Ottoman history. In the decades after Suleiman, the empire began to experience significant political, institutional, and economic changes, a phenomenon often referred to as the Transformation of the Ottoman Empire. The empire battled rising inflation, so serious that it contributed to the rise of local strongmen and put pressure on relations with Europe and the Middle East. Ottoman fiscal insolvency and local rebellion, together with the need to compete militarily against their imperial rivals, the Habsburgs and Safavids, created a severe crisis. The Ottomans thus transformed many of the institutions that had previously defined the empire, gradually disestablishing the Timar land grant system in order to raise modern armies of musketeers and quadrupling the size of the bureaucracy in order to facilitate more efficient collection of revenues.

Perhaps as a distraction from problems at home, Suleiman turned to empire building, and this resonated with his successors. He expanded into southern and eastern Europe. Indeed, the Ottomans nearly captured Vienna twice (in 1529 and again in 1683). They controlled shipping in the western Mediterranean and the trade routes and major markets connecting to the Silk Road such as Cairo and Baghdad. They also extended their influence well across the Indian Ocean by supporting the Acehnese Sultanate on the island of Sumatra (now part of Indonesia). The high cost of doing business in the Ottoman-controlled Middle East created an incentive for European merchants to seek other ways of reaching Asia. The Ottomans were actually quite tolerant of ethnic, language, and religious diversity, and their empire was multiethnic and multicultural. Following long-standing traditions within Islam, they granted a protected minority status to “peoples of the book,” meaning the Bible, and primarily including Christians and Jews. Local languages, religions, and even self-government were allowed if those with dhimmi status remained loyal to the empire and paid a jizya tax levied over and above the regular taxes.

Although no one knows quite how it started, the Ottomans created the devsirme system to recruit and train loyal soldiers and bureaucrats. The Ottomans often took a quota of young boys who were brought to training schools near Istanbul. This happened in places like those western Christian Balkans region that were too poor to pay taxes in money or produce. Many boys were taken forcibly, some were turned over willingly to ease the family burdens, and some volunteered for the chance at a better education or lifestyle. Those taken were converted to Islam, educated, and trained into an elite fighting force called the Janissaries, who reported directly to the emperor. Or, depending on their skills, they might serve in the bureaucracy. Because they were personally loyal to the sultan, the Janissaries became politically powerful. Fear that the private army would betray him and name another heir sultan caused new rulers to assassinate all their brothers as soon as they took the throne. The Janissaries were the Ottomans’ most effective weapon from 1363 to 1826, when the sultan decided to disband them in favor of a modern military. The Janissaries mutinied and marched on the sultan’s palace, but several thousand were wiped out by modern artillery and the survivors executed.

The Ottoman Empire tried to modernize in other ways as well but fell behind its European neighbors in the 19th century and finally met its end during the First World War. We’ll return to that story in a few chapters.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Istanbul rapidly become the largest city outside China?

- What features of Ottoman rule help explain the troubled successions?

- Why was it dangerous that the Janissaries reported personally to the sultan?

The Safavid Empire

The Safavid Empire of Persia (1501–1736) was controlled by a Shiite Muslim dynasty that spread its influence across the region from the eastern border of the Ottoman Empire, through Iran, and into what is now Afghanistan, Georgia, Armenia, and Pakistan. The cultural influence of the Safavid Empire also extended well beyond its territorial bounds, into Central and South Asia, as well as parts of Africa and Southeast Asia. The western borders of the Mughal Empire flanked it on the other side, yet it is notable that much of the culture of the Mughal court was strongly influenced by Persian culture. Indeed, Persian was widely spoken as a court language in Central and South Asia, and the influence of Persian Sufi traditions remains in these regions up through the present, even though the Safavid Empire was the smallest and least powerful of three Muslim empires and nestled in between the larger two. As the Ottoman and Mughal Empires expanded, they seemed reluctant to move into Safavid lands, but with little other room to move, it became inevitable.

The Safavid’s greatest ruler, Shah Abbas the Great, moved his capital to Isfahan in central Iran. The ancient Persian city had once been a home for Israelite refugees freed from the Babylonian Captivity by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE. Shah Abbas continued the tradition of settling refugees in Isfahan, welcoming hundreds of thousands of Armenians in the early 1600s from the disputed border region separating the Shiite Safavid Empire from the Sunni Ottoman Empire. After the Armenian genocide in 1915, during World War One, the Armenian quarter of Isfahan became one of the oldest and largest Armenian centers in the world. After his attempt to improve relations with the Armenians at the expense of the Ottoman empire, Shah Abbas turned to the Mughal Empire in an effort to seize Kandahar in current-day Afghanistan and then clashed with the Russian Empire in the Caucasus in the 1650s.

The Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire of India was founded in 1526 by Babur, who was from a Persian speaking dynasty and of Turko-Mongolian Muslim heritage. Babur was the great-great-great grandson of Timur, or “Tamerlane,” and there were claims that Timur was a relation of the Mongol khans. However, historians have established that there is no confirmable link between Timur and Genghis Khan himself. Although “Moghal” is a Central Asian term originating from Persian pronunciations of the word “Mongol,” the word “Mughal” at the time in Central Asian Persian did not have the precisely same meaning as the term “Mongol” does for us today. Instead, it was a type of hybrid identity. The evidence suggests Babur’s own background and the community he ruled over was composed of a blend of Turkic, Persian, and Mongolian cultures. At the time of his rise to prominence, many Central Asian elites had already been speaking and writing forms of Persian languages for hundreds of years, and the Persian connection proved important for Babur. With the aid of Persian forces, Babur defeated Sultan Ibrahim Lodi of Delhi and then asserted the legitimacy based on his connection to the legacy of Timur.

The Mughals led an Islamic empire and initially battled the Hindus and Sikhs. Sikhism had developed in the Punjab in the 15th century by combining elements of the traditional Hinduism of the region with Islam. Sikhs opposed India’s caste system while becoming legendary warriors on the subcontinent. Eventually, they came to terms with the Hindu population and their rule stabilized. The Mughals (from whom we get the term mogul) ruled a wealthy empire that included most of the Indian subcontinent and large parts of Afghanistan. It lasted until 1857 and at its peak ruled a population of over 150 million people.

The Mughal golden age began in 1556 with the reign of Akbar the Great, who expanded the empire’s territory but allowed his Indian subjects to keep their languages and religions. Hinduism, which is still the dominant religion of India, is based on a variety of philosophies, ancient traditions, and practices. The supreme god and creator Brahma became part of a trinity with Shiva, whose role it is to destroy the universe in order to re-create it, and Vishnu, the preserver of the universe. Beliefs centered on dharma (ethics), artha (purpose), kama (passions), and moksha (liberation from passion and the cycle of birth and rebirth). Unlike Muslims and Christians, differences related to religious practice have rarely divided Hindus; however, several “streams” or branches have evolved around Vishnu (Vaishnavism) and Shiva (Shaivism).

Through warfare and diplomacy, Akbar (r. 1556–1605) was able to extend the empire in all directions and controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent. He created a new ruling elite loyal to him, implemented a modern administration, and encouraged cultural developments. He increased trade with European trading companies. India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and economic development. Akbar allowed freedom of religion at his court and attempted to resolve sociopolitical and cultural differences. Akbar himself was influenced by Sufi mysticism. In 1575, he built the Ibadat Khana and encouraged discussion among intellectuals of various religions, although this was not always welcomed by the orthodox theologians.

Akbar left his son Jahangir an internally stable state, which was in the midst of its golden age, but before long, signs of political weakness would emerge. It was his son Shah Jahan who would show the splendor of the Mughal court by building the Taj Mahal in 1631. The cost of maintaining the court, however, soon began to exceed revenue. In 1658, a younger son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), seized the throne. During Aurangzeb’s reign, the empire gained political strength once more and became the world’s most powerful economy. Aurangzeb encouraged conversion to Islam; compiled the Fatwa Alamgiri, a collection of Islamic law; and extended the jizya tax along with the protections of the dhimmi status to Hindus. He expanded the empire to include almost the whole of South Asia, but at his death in 1707, many parts of the empire were in a state of unrest.

Aurangzeb is considered the Mughal Empire’s most controversial king, and his religious conservatism and intolerance undermined the stability of Mughal society; despite that, his legacy has become controversial in South Asian political contexts. He offered funds to construct far more Hindu temples than the Mughal military destroyed as a function of expansionist practices during his reign, employed significantly more Hindus in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors did, opposed bigotry against Hindus and Shia Muslims, and married Hindu Rajput princess Nawab Bai.

Still, after Aurangzeb’s reign, the Mughal dynasty fractured, and internal feuds took over. By 1720, after a century of growth and prosperity, the Mughal Empire declined and lost significant territory to the Maratha Empire. The emperor lost authority as the widely scattered imperial officers lost confidence in the central authorities and made their own deals with local men of influence. Next time we encounter India, we’ll take a look at the arrival of the British.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were the Ottomans and the Safavids always at war?

- What was the advantage for empires like the Mughal of letting subject peoples retain their languages, religions, and customs?

- What attracted Peter the Great to study Europe?

Europe at 1500

Europe’s Dark Ages ended in the 15th century, after the disaster of the Black Death. Feudal lords squeezed their peasants for crops and labor, and states raised taxes. Several million died during the famine, and then two-thirds of Europe’s population disappeared between the plague’s arrival in 1347 and 1353. This depopulation threatened the power of the church and the nobility, as surviving peasants became less patient with the taxes and labor demands of their bishops and lords. Peasant revolts in France and England in the second half of the 14th century showed that the feudal system of the Middle Ages was coming to an end.

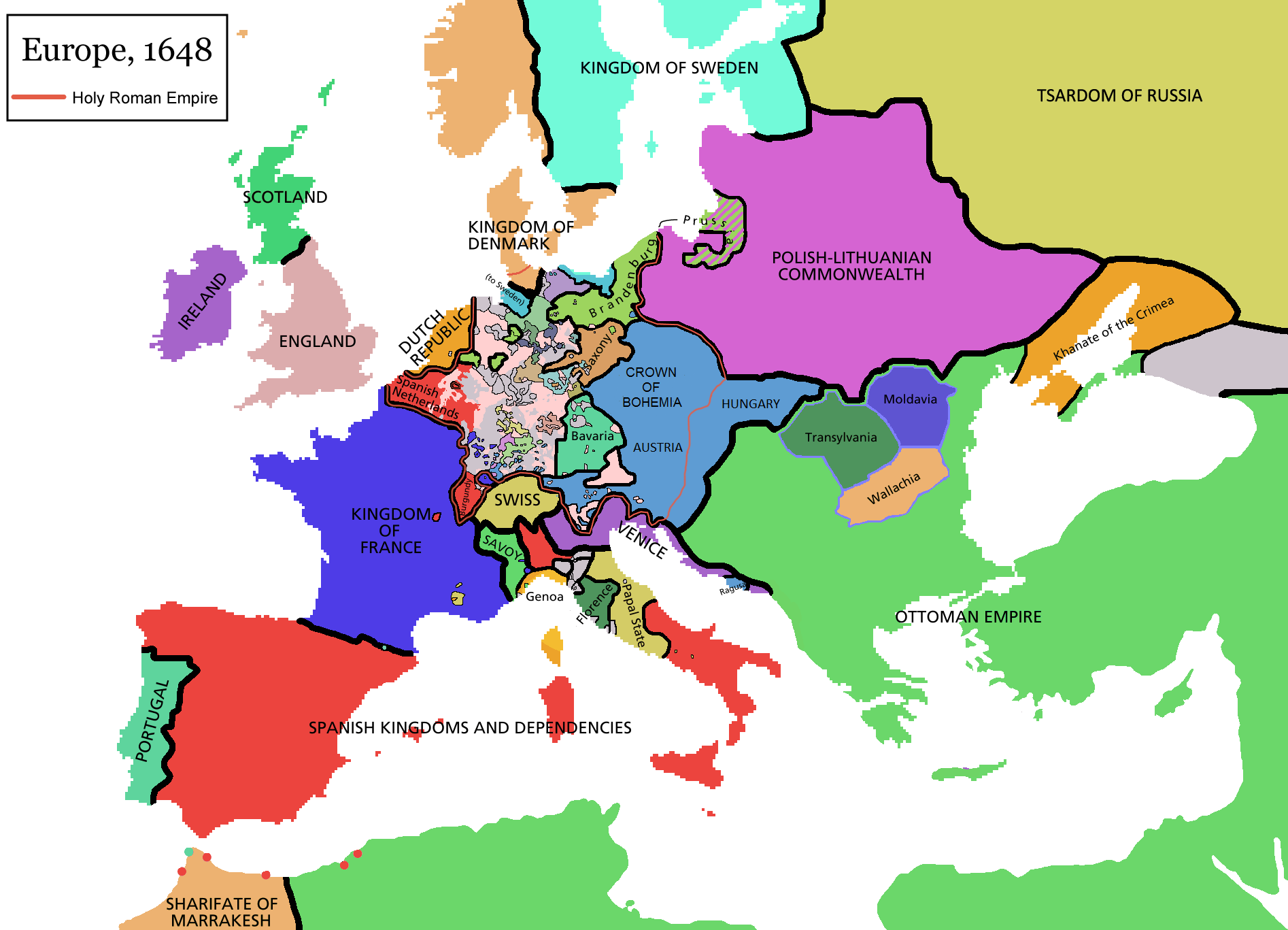

Unlike the new Muslim empires and the continuing Ming Chinese Empire, Europe was unable to reunify under a single leader and create its own empire—although Austria’s Hapsburg dynasty did its best to lead an alliance optimistically named the Holy Roman Empire until it was dissolved in 1806. Too many languages and local centers of power competed for dominance, and the Catholic Church (Europe’s largest landowner) was unable to exercise secular as well as spiritual power. Instead, the church found itself pulled into regional contests for power, and in 1309, a French-born pope moved his residence to Avignon. Seven popes resided in France under the control of the French king until 1378, when another French-born pope decided to move back to Rome. But the French rulers and a growing class of aristocratic French cardinals were unwilling to give up the power that came with having their own pope. For another sixty years, there were two competing papal courts, one in Rome and a rival in Avignon. Although the Avignon popes have been called antipopes, it’s important to understand that the conflict was primarily about political power rather than about theology or religious doctrine. But theological conflicts were right around the corner.

Italy

During the late Middle Ages, northern and central Italy became far more prosperous than the south of Italy, with the city-states, such as Venice and Genoa, among the wealthiest in Europe. The Crusades had built lasting trade links to the Levant and had done much to destroy the Byzantine Empire as a commercial rival to the Venetians and Genoese. Florence too would take its role in the first half of the 15th century. There, the House of Medici was an Italian banking family, political dynasty, and later royal house that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de’ Medici.

The main trade routes from the east passed through the Byzantine Empire or the Arab lands and onward to the ports of important cities such as Genoa, Pisa, and Venice. These cities not only fought among themselves but also maintained a long-running battle for supremacy between the forces of the papacy and of the Holy Roman Empire. Luxury goods bought in the Levant, such as spices, dyes, and silks, were imported to Italy and then resold throughout Europe. Moreover, the inland city-states profited from the rich agricultural land of the Po Valley. From France, Germany, and the Low Countries, through the medium of the Champagne fairs, land and river trade routes brought goods such as wool, wheat, and precious metals into the region. The extensive trade that stretched from Egypt to the Baltic generated substantial surpluses that allowed significant investment in mining and agriculture.

France and England

Italy was not the only place where warfare caused upheaval. The Hundred Years’ War is the term used to describe a series of conflicts from 1337 to 1453 between the rulers of the Kingdom of England and the House of Valois for control of the French throne. These 116 years saw a great deal of battle on the continent, most of it over disputes as to which family line should rightfully be upon the throne of France. The root causes of the conflict can be found in the demographic, economic, and social crises of 14th-century Europe. The outbreak of war was motivated by a gradual rise in tension between the kings of France and England about Guyenne, Flanders, and Scotland. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, the population of France was about half what it had been before the era began.

Although primarily a dynastic conflict, the Hundred Years’ War gave impetus to ideas of French and English nationalism. By its end, feudal armies had been largely replaced by professional troops, with new weapons and tactics, and aristocratic dominance had to share influence with the rising military professionals. The war precipitated the creation of the first standing armies in Western Europe since the time of the Western Roman Empire, composed largely of commoners and thus helping to change their role in warfare. For example, Charles VII of France created the first standing army to expel the English from all but Calais, expanded taxes, and extended influence to lawyers and bankers at the expense of noble influence. His son Louis XI conquered Burgundy and later Anjou, Maine, and Provence. Louis XII added Brittany by marrying Anne and made an agreement with the pope to appoint bishops and abbots, and thus heavily influenced church policy, in return for taxes.

Deprived of its continental possessions, England was left with the sense of being an island nation, which profoundly affected its outlook and development for more than 500 years. English political forces over time came to oppose the costly venture. The dissatisfaction of English aristocracy resulting from the loss of their continental landholdings became a factor leading to the civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487). The house of York (represented by a white rose) and the house of Lancaster (represented by a red rose) fought for control of England. After Edward IV defeated Lancaster in 1471, he also looked for ways to reduce the power of the nobility, as did his successors, Richard III and Henry VII, who was from the house of Tudor. He limited his reliance on nobles, particularly in his royal council, and instead turned to smaller landowners for support. He also extended his influence through marriage, beginning with his son Arthur’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella. Henry called on Parliament when he thought it would be to his advantage and used the courts to squelch noble independence. His son Henry VIII would build on these tactics, as we will see later.

The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a multiethnic complex of territories in central Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806. The boundaries changed over the centuries, but the core consisted of the eastern lands of Charlemagne’s empire and included territory from Saxony to Bavaria, Bohemia, Burgundy, areas of northern Italy, and numerous other territories. The term Holy Roman Empire was not used until the 13th century, and the office of Holy Roman Emperor was traditionally elective, though frequently controlled by dynasties. The German princes, the highest-ranking noblemen of the empire, usually elected one of their peers to be the emperor, and he would later be crowned by the pope (although the tradition was discontinued in the 16th century). In time, the empire evolved into decentralized, limited monarchies composed of hundreds of subunits, principalities, duchies, counties, free imperial cities, and other domains. It was divided into dozens—eventually hundreds—of individual entities governed by kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other rulers who governed their land independently from the emperor, whose power was severely restricted by these various local leaders.

The Iberian Peninsula: Spain and Portugal

In 1469, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile married and became known as the Catholic Monarchs. They brought together the two largest provinces in Spain and took a big step toward unifying the Iberian Peninsula. Reforms aimed at reducing the powers of the nobles, as had England and France before them. With the support of the pope, they began to appoint bishops, and in 1480, they further consolidated their power by establishing the Spanish Inquisition, a judicial court to root out heresy. It covered Spain and all the Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. The court targeted hundreds of those who had converted to Catholicism but were accused of secretly practicing their original religion (Judaism or Islam). They were arrested, imprisoned, interrogated under torture, and in some cases, burned to death in both Castile and Aragon. In 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella entered Granada, a symbolic victory that ended Muslim rule of a territory in Europe. They ordered the segregation of communities to create closed quarters that became what were later called “ghettos.” They also furthered economic pressures upon Jews and other non-Christians by increasing taxes and social restrictions. Tens of thousands of Jews emigrated to other lands.

The Kingdom of Portugal was a long-lived monarchy on the western coast of the Iberian Peninsula. In 1418, Portuguese sailors began exploring the coast of Africa and the Atlantic archipelagos using recent developments in navigation, cartography, and maritime technology such as the caravel with the aim of finding a sea route to the source of the lucrative spice trade. The Portuguese worked their way down the west coast of Africa and in the 1480s convinced the king of Kongo, Nzinga a Nkuwu, to convert to Christianity. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India. In 1500, either by an accidental landfall or by the crown’s secret design, Pedro Álvares Cabral reached what would be Brazil.

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways was the Christian church a dominant force in Europe?

- What factors explain the rise of nationalism?

- How did the conflict between England and France help shape European politics?

The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire grew out of resistance to Mongol rule and the fall of Constantinople. A ruler of the Grand Duchy of Moscow named Ivan III (later called Ivan the Great) refused to pay tribute to the Golden Horde, and after the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor, Ivan decided his kingdom would become the new Rome. Ivan (r. 1462–1505) tripled the size of his state and rebuilt the Kremlin in Moscow. His grandson Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible, r. 1547–1584) was the first to declare himself tsar of all the Russians—a title that is Russian for “Caesar.” He annexed the khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia and recruited Cossacks from southern Russia and Ukraine to colonize Siberia. The Cossacks were an Eastern Slavic group of semi-nomadic people who maintained an independence from the Russian government in exchange for military service.

Ivan IV left an indelible mark on Russia. Despite Ivan IV’s reputation as a paranoid and moody ruler, he made some positive steps that would provide the foundation for the later Russian state. He revised the law code, the Sudebnik of 1550; initiated a standing army (the streltsy); developed the Zemsky Sobor, a quasi-parliament; and brought the church more firmly under his purview. The first printing press came to Russia, and he oversaw the construction of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow.

In 1564, after years of drought and famine and invasions, Ivan fled Moscow. A group of boyars went to beg Ivan to return in order to keep the peace, and he agreed with the understanding that he would be granted absolute power. Ivan then instituted what is known as the oprichnina. The oprichnina split the Russian lands, giving some to the state (Ivan) and some to the boyars to manage. This land policy entrenched peasant obligations and lengthened feudalism in the east. Ivan IV executed, exiled, or forcibly removed hundreds of boyars from power, solidifying his legacy as a paranoid and unstable ruler. Ivan IV left the economy unstable and fertile lands a wreck. Wars were drawn out and costly. Legend also suggests he murdered his son Ivan Ivanovich, whom he had groomed for the throne, in 1581, leaving the throne to his childless son Feodor Ivanovich.

The Time of Troubles occurred between 1598 and 1613 and was caused by severe famine, prolonged dynastic disputes, and outside invasions from Poland and Sweden. The worst of it ended with the coronation of Michael I in 1613, who officially founded the Romanov dynasty, one that stayed in power until the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917. Peter the Great shared the throne until 1696 and ruled until 1725. He built a new capital in St. Petersburg. He is also remembered for bringing western culture and Enlightenment ideas to Russia as well as limiting the control of the church.

Russia became the largest kingdom in the world, stretching from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, but much of it was unoccupied and primitive. Peter I (Peter the Great, r. 1672–1725) visited Europe in disguise for 18 months to study shipbuilding and new administrative techniques that he used to modernize his realm and establish the Russian Empire. We’ll return to Russia later, during the reign of Peter in the late 1600s.

Questions for Discussion

- How does the Russian Empire compare to the Islamic ones?

- What problems did Ivan IV leave behind?

- What attracted Peter the Great to study Europe?

The Empires of Africa, ~1500

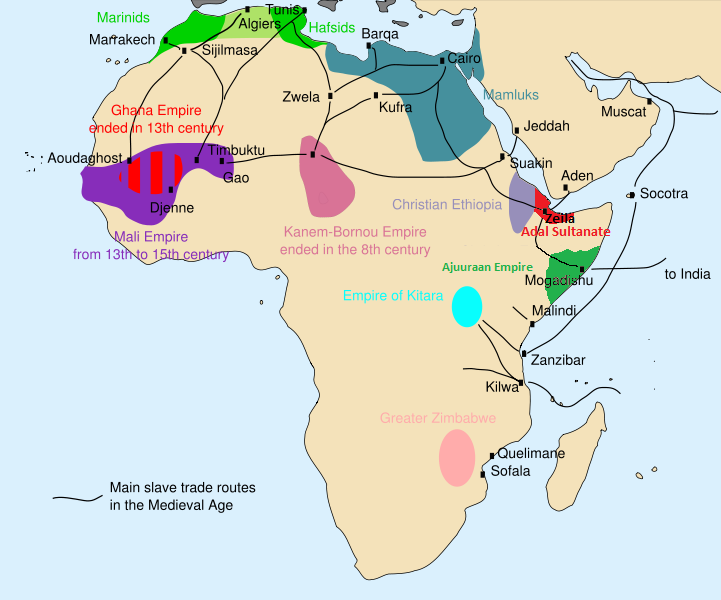

Along with the Americas, Africa largely remained outside the global interactions. The long trip across the Sahara Desert or around the Atlantic Ocean and the localized cultures within the large continent tended to encourage African isolation. Still, a number of empires appeared in Africa.

West Africa

The trade across the Sahara defined West Africa, brought Islam to the region, and linked it to the world across the Mediterranean. The Mali Empire lasted from 1230 to 1600 and built upon the trade niche created by its predecessor, Ghana. Ghana enjoyed a vibrant role as the “middleman” in trade between sub-Saharan suppliers of gold and North African salt. Sundiata Keita was the first ruler of the Mali Empire in the 13th century C.E. Some believe that Arab traders in the area converted Keita to Islam.

By the beginning of the 14th century, Mali was the source of almost half the Old World’s gold. The Mali Empire reached its largest size under Mansa Musa. Mansa Musa, a devout Muslim, most famously made a trip across northern Africa to the Arabian Peninsula to attend the hajj in Mecca. With a conservative estimate of 25,000 in his retinue, he traveled across northern Africa. He paid for everything in gold and in Cairo handed out so much of the precious metal that he literally ruined the economy of Egypt for over a decade. While in Mecca, he met with local intellectuals and convinced them to return to Mali. The laws of the Koran were now also integrated into the judicial system of Mali. He embarked on a large building program, raising mosques and madrasas in Timbuktu and Gao. Poets and scholars and others flocked to his new cities, which quickly became cultural centers.

In the second half of the 14th century, disputes over succession weakened the Mali Empire, and in the 1430s, Songhai, previously a Mali dependency, gained independence and greatness with its leader Sonni Ali (r. 1464–1492). Ali conquered many lands, repelling attacks from the Mossi to the south and overcoming the Dogon people to the north. He annexed Timbuktu in 1468, although he met stark resistance from the city of Djenné, but was finally able to incorporate it into his empire in 1473.

The Songhai economy was based on a clan system. The clan a person belonged to ultimately decided one’s occupation, from lower-caste labor, to metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters, to upper-class noblemen. Askia the Great strengthened the Songhai Empire and made it the largest empire in West Africa’s history. Slaves played an important role in the economy and usually were either captured in battle or sold into slavery to pay off a debt. Askia relied on slaves to complete the hardest work, transporting goods northward, and to serve as soldiers and even royal advisors. His policies resulted in a rapid expansion of trade with Europe and Asia, the creation of many schools, and the establishment of Islam as an integral part of the empire. However, as Askia the Great grew older, his power declined, and his sons revolted against him. Morocco invaded Songhai in 1591 to seize control of the trans-Saharan trade in enslaved people, salt, and gold.

Medieval to Modern Ethiopia

Around 1270, a new dynasty was established in the Abyssinian highlands under Yekuno Amlak, who deposed the last of the Zagwe kings and married one of his daughters. According to legends, the new dynasty were male-line descendants of Christian Aksumite monarchs of the 10th century and claimed lineage to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. The Solomonic dynasty began with links to the Egyptian Coptic Church and later formed its own Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity. The 14th-century legend was created to legitimize the Solomonic dynasty, under which the chief provinces became Tigray (northern), what is now Amhara (central), and Shewa (southern). The seat of government—or rather, of overlordship—was usually in Amhara or Shewa, and the ruler exacted tribute, when he could, from the other provinces.

Toward the close of the 15th century, Portuguese missions into Ethiopia began. A belief had long prevailed in Europe of the existence of a Christian kingdom in the Far East whose monarch was known as Prester John, and various expeditions had been sent to find it.

In the 18th century, the so-called Zemene Mesafint (Era of the Princes) began. It was a period in Ethiopian history when the country was divided into several regions with no effective central authority. The emperors were reduced to little more than figureheads confined to the capital city of Gondar. A religious conflict between settling Muslims and traditional Christians, between the nationalities they represented, and between feudal lords dominated the region at the time. The power lay ever more openly in the hands of the great nobles and military commanders.

Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe is an ancient city center, the ruins of which are in the southeastern hills of today’s Zimbabwe. The exact identity of the Great Zimbabwe builders is, at present, unknown. Local traditions assert that the stonework was constructed by the early Lemba. However, the most popular modern archaeological theory is that the edifices were erected by the ancestral Shona.

The ruins at Great Zimbabwe are the second oldest south of the Sahara, after nearby Mapungubwe in South Africa. Great Zimbabwe existed between circa 1220 and 1500. At its peak, estimates are that Great Zimbabwe had as many as 18,000 inhabitants. The ruins that survive are built entirely of stone, and they span 730 ha (1,800 acres). The rulers of Zimbabwe brought artistic and stone masonry traditions from Mapungubwe and expanded their influence by taxing other smaller rulers throughout the region. Their kingdom was composed of over 150 tributaries headquartered in their own minor zimbabwes (stone structures).

Great Zimbabwe became a center for trading, with a trade network linked to Kilwa Kisiwani (off the southern coast of present-day Tanzania in eastern Africa) and extending as far as China. This international trade was mainly in gold and ivory. Some estimates indicate that more than 20 million ounces of gold were extracted from the ground. Asian and Arabic goods could be found in abundance. The Great Zimbabwe people mined minerals like gold, copper, and iron. Chinese pottery shards, coins from Arabia, glass beads, and other nonlocal items have been excavated. That international commerce was in addition to the local agricultural trade, in which cattle were especially important. The large cattle herd that supplied the city moved seasonally and was managed by the court. Archaeological evidence also suggests a high degree of social stratification, with poorer residents living outside of the city.

Causes suggested for the decline and ultimate abandonment of the city of Great Zimbabwe have included a decline in trade compared to sites farther north, the exhaustion of the gold mines, political instability, and famine and water shortages induced by climatic change. Around 1430, Prince Nyatsimba Mutota from Great Zimbabwe traveled north in search of salt among the Shona-Tavara. He defeated the Tonga and Tavara with his army, and the land he conquered would become the Kingdom of Mutapa. Within a generation, Mutapa eclipsed Great Zimbabwe as the economic and political power in Zimbabwe. By 1450, the capital and most of the kingdom had been abandoned.

The Americas

Mayans

The people living in the Americas had been separated from Eurasia for nearly 12,000 years, since the end of the Ice Age. During this period, Native Americans experienced their own agricultural revolution around the same time as Africans and Eurasians, but instead of domesticating cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, and chickens (which were not native to the Americas), they developed certain plants, creating three of the world’s current top five staple crops—corn, potatoes, and cassava—as well as additional plants such as hot peppers, tomatoes, beans, cocoa, and tobacco.

Reliable, storable, staple food supplies are a necessary precondition for long-term settlement and population growth—in other words, the creation of cities. Like the Europeans, Africans, and Asians, once they had created a reliable food supply, American natives built remarkable cities, especially in Central and South America. From present-day Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula south through Guatemala, the Maya developed a complex society that reached its most intense flourishing during their “Classic Period” (250 CE–900 CE). However, by the time the Spanish arrived, the Maya were living in more separated, independent city-states, seemingly having abandoned some of their more impressive temples and structures such as Chichén Itzá in Yucatán. Their population had spread well into the Central American uplands.

Religion and governance intertwined in Maya society, and stories of gods and goddesses were fundamental in the building of temples and determining the best times for planting and harvest. The Maya origin story, Popul Vuh, is surprisingly similar to that found in the Judeo-Christian book of Genesis. Corn and the god related to corn were the principal concern for Maya religion and society. To record their beliefs and run their complex society, the Maya developed a written language based on 800 hieroglyphs that represented different syllables. They also developed a base-20 number system that included “zero” independent of South Asian and Arabian notions of zero and centuries before the concept was introduced into Western Europe. The preciseness of Maya mathematics, along with the importance of the stars and planets to their religious beliefs, allowed the Maya to be more advanced than the Europeans in astronomy and to develop a more exact calendar.

Mayan religious beliefs included scraping down and redecorating their temples every sixty years. One famous carved calendar used to calculate the precise time for this renovation and other key ceremonies ended on December 21, 2012, leading many to believe that the Maya had predicted the end of the world. In reality, it seems that the astronomers had simply run out of room on that particular calendar.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it significant that several pre-Columbian cultures were not at their peaks when the Europeans arrived?

- How does the existence of a written language alter how we think of people’s level of civilization?

Aztec and Inca origins

Building on the Olmec stone culture, the Nahua people and possibly others built the structures of Teotihuacán between 100 BCE and 750 CE. The Aztecs claimed an ancestry to the inhabitants of Teotihuacán and transformed the cities of Tenochtitlán and Texcoco, built in the 1320s in the Valley of Mexico. Each city had more than 200,000 inhabitants when they were first encountered by the Spanish, making them as large as Paris and Milan, Europe’s most populous cities at the time. Tenochtitlán was built on an island in Lake Texcoco and was connected to the lakeshore by a series of causeways. The Aztecs would go on to build an agricultural empire in the region and subjugate the Mexican peoples in the process.

In South America, the settlement of Tiwanaku, located near the shores of Lake Titicaca in what are now the Bolivian highlands, was built about 3,500 years ago. Its 30,000 inhabitants developed a farming technique called flooded-raised field agriculture which covered the hills around the lake with walled terraces. Later, the Inca will build on this way of life. We will return to Aztec and Inca history in the next chapter and take a closer look at their culture on the eve of the European arrival to the Americas.

The five regions—Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas—were each exceptional in their global connection. Their governance, culture, and movement were crucial factors in shaping their histories and, by extension, world history. In particular, Muslim empires, sultanates, and kingdoms formulated connections that stretched from Southeast Asia, through South and Central Asia, to Southwest Asia, Eastern Africa, Northern Africa, and Western Africa while also including incursions in Europe. However, late classical and early modern non-Muslim societies in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and yes, even Europe, also forged transregional connections. By summarizing each region, we hope to encourage a view of history that presents an objective and equitable starting point at 1500.

Media Attributions

- The Great Wall of China at Jinshanling-edit © Severin.stalder is licensed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Verbotene-Stadt1500 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ottoman Empire © CIA is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Battle_of_Vienna.SultanMurads_with_janissaries © G. Jansoone is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_maximum_extent_of_the_Safavid_Empire_und er_Shah_Abbas_I © Arab Hafez is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Taj Mahal (Edited) © Yann Forget, edited by Jim Carter is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Europe map 1648 © by unknown is licensed a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Avignon, Palais des Papes by JM Rosier © Jean-Marc Rosier is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Ivan the Terrible and Horsey © Alexander Litovchenko is licensed under a Public Domain license

- African slave trade © Runehelmet derived from Aliesin is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike unported) license

- Gondar Fasiladas Bath Timket © Jialiang Gao is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike unported) license

- Chichen_Itza_3 © Daniel Schwen is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Intikawan_Amantani © PjH is licensed under a Public Domain license