7 The Great War

In 1914, the states and empires of Europe had been mostly officially “at peace” with one another for nearly a century. However, the official peace covered a growing tension that was beginning to flare up into military conflict. The unification of Germany in 1870, after the Prussian-led victory over the French, had created a new nation with imperial aspirations in the middle of Europe. Bismarck’s new empire competed with neighboring countries in industry, agriculture, and overseas empire building. The existence of a united Germany upset the careful balance of power created by the Congress of Vienna in its effort to reset the clock and redraw the map after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. France and Germany were enemies and sought alliances against each other. Furthermore, business elites from these empires contested with one another for influence in the economies of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. By 1914, most governments in Europe were preparing for an eventual war between these groups of allied nations, although no one knew what incident would bring the continent to battle. But as early as 1888, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had predicted that “some damned foolish thing in the Balkans” could initiate a conflict. He was proven correct on the streets of Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

During World War I, the principal members of each of these alliances were the “Central Powers,” consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire, against the “Allied Powers,” which at the beginning of the war was called the “Triple Entente” after the original allies, France, Great Britain, and Russia. As a result of the Russian Revolution, which overthrew the tsarist regime, Russia left the war in 1918. Italy joined the allies in 1915, and Japan was an additional ally on the French side, which would result in a Japanese routing of the German navy in the South Pacific. The United States entered the war to support the allies in 1917.

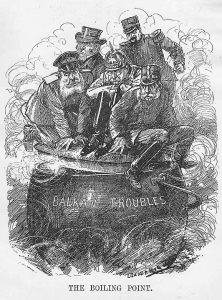

The underlying causes of World War I were nationalism, opposition to foreign rule, and simmering rivalries between the Great Powers that were exacerbated by treaties requiring allies to enter a war once it began. Previously, potential world conflicts had been avoided through negotiation among the Powers. Africa was divided among the European empires at the Berlin Conference in 1885, while “spheres of influence” were established in China in order to regulate trade. However, such a “Concert of Nations” did not succeed in the Balkans.

The unification of Germany upset the balance of Europe. Not only did the Deutsches Reich aspire to become an imperial power like Britain, France, and Russia; it had rapidly built up its military and industrial power. By the first two decades of the twentieth century, Germany surpassed Britain to become the largest economy in Europe and second in the world. German scientists won more Nobel Prizes than any other nation besides the United States. And Germany’s navy was racing to surpass Britain’s.

In 1888, Kaiser Wilhelm II took the imperial throne when both his grandfather and father died in rapid succession. Wilhelm I, the king of Prussia whom Bismarck had made an emperor, ruled until he was 90. His grandson took the throne at 29. Due to the elaborate intermarriages of the European ruling families, Wilhelm II was also the eldest grandson of Queen Victoria of England. Wilhelm II launched Germany on a “New Course” toward overseas imperialism. The kaiser ordered his military leaders to read Alfred Thayer Mahan’s book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, which had also influenced Theodore Roosevelt in America. By 1914, the German navy was second only to the British Royal Navy. The new emperor also dismissed Bismarck as chancellor in 1890 and began looking for ways to make Germany a colonial empire through a much more aggressive foreign policy than that envisioned by his chief advisor.

The eighty-four-year-old Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Josef had been reigning since 1848. His nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (age 50), was the crown prince and expected to soon become the next emperor. In the area of Western Europe between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea called the Balkan Peninsula, the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires each claimed control. As described in the previous chapter, the Ottomans had gradually been losing power, including among their territories in Europe, since the 1700s. By the end of the nineteenth century, the newly independent kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Montenegro, and Serbia separated the Muslim Ottomans from the Catholic Austro-Hungarians. The Orthodox Russians of the Slavophile movement dreamed of reestablishing Constantinople in Istanbul and felt a kinship with their fellow Orthodox Slavs, the Serbs and Bulgarians.

The Balkan conflict Bismarck had predicted began in 1908 with the Austro-Hungarian takeover of Bosnia from the Ottoman Empire. Many Serbs lived in Bosnia, so Serbian nationalists wanted it to be part of Serbia. The Serbs and Bulgarians deepened their alliance with the Russians, who also wanted to check the expanding influence of the Austrians in the Balkans.

The independent kingdoms of the Balkans fell into war in 1912–1913, first with the Ottomans, resulting in an independent Albania, and then with each other as ethnic and religious boundaries were contested. These were bloody conflicts that included attacks on civilian populations in waves of ethnic cleansing—people living in this region would experience similar massacres in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. The Balkan armies on both sides dug into trenches as new arms and technology limited the movement of troops.

In an effort to strengthen Bosnian ties to Austria, Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife made an official visit to the regional capital of Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. A secretive Serbian nationalist group, which had been encouraged and supported by Serbian military officers, plotted the assassination of the royal couple as their motorcade made its way through the city. After some initial bungling, one of the conspirators, nineteen-year-old Gavrilo Princip, shot and killed the archduke and his pregnant wife.

The Austro-Hungarian government made a series of demands for restitution from the Serbian government. When Serbia refused, Austria decided to invade. Germany was bound by its treaty obligations to support any action taken by its ally Austria-Hungary. Austria’s invasion of Serbia activated the European alliance system: Russia sided with the Serbs, France supported Russia, and Great Britain was allied with France.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the main causes of the world war? Was it inevitable?

- Did the tangled relationships of European rulers contribute to stability or instability?

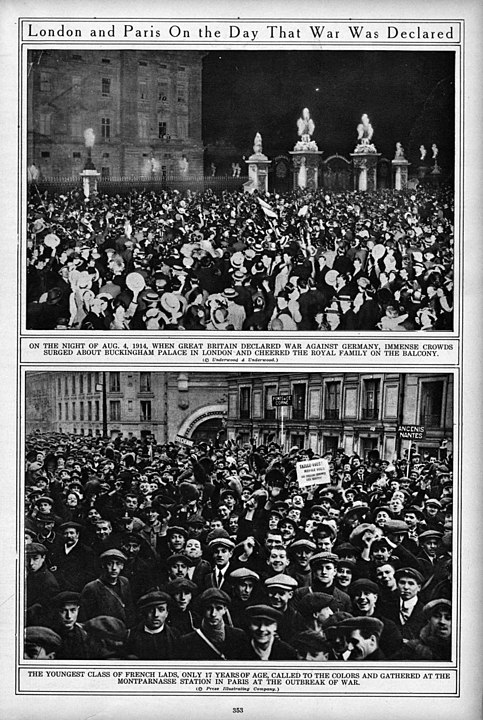

Many of Europe’s armies had been preparing for a continent-wide conflict since the unification of Germany in 1870. Most empires required some form of military service from all young men so that thousands of trained reserve soldiers could be quickly called up. All war plans relied on the quick mobilization of troops, and the extensive European railway network built in the nineteenth century moved regiments more rapidly than in any previous war. This rapid deployment meant that as soon as one side mobilized, the opposing side also had to mobilize in defense. Less time was available for calm decision-making as every nation rushed to arms. In July 1914, when Austria declared war and shelled the Serbian capital, Belgrade, Russia mobilized its military. Germany mobilized against Russia. Russia was allied with France, so France mobilized. Great Britain was allied with France, so Great Britain mobilized. The Ottomans sided with Germany as a counter to Russia. Italy, which had a defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, sat out of the first months of war until its government decided to side with France, Great Britain, and Russia in early 1915.

![By Unknown German war photographer, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11072391 Nine German soldiers hanging out of supply train with their arms raised some with flowers others waving or raising their clenched fists. Messages on the car spell out (approximately): "Trip to Paris", "See you later on the Boulevard", "[obscured by flowers] the fight" (The obscured part most likely reads "Auf in [den Kampf]" which means "Into battle"), "my sword tip is itching".](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/18/2022/05/640px-German_soldiers_in_a_railroad_car_on_the_way_to_the_front_during_early_World_War_I_taken_in_1914._Taken_from_greatwar.nl_site-300x212.jpg)

Because of the French-Russian alliance, the Germans knew that they would face a two-front war in any European-wide conflict. Expecting to face enemies on Germany’s eastern and western borders, the German generals had been planning for years to initially fight a defensive war with Russia in the east and an offensive war with France in the west, holding off invading Russian armies while focusing on defeating the French first.

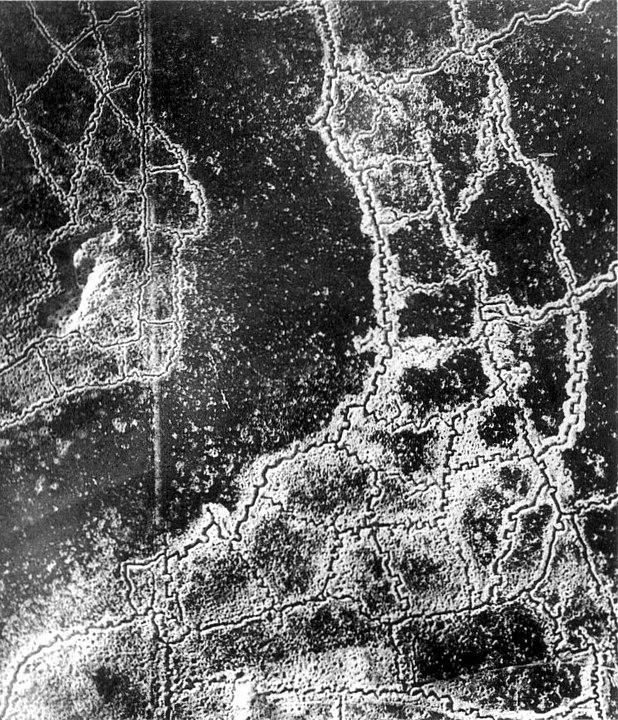

In the first months of the war, the Germans were successful in carrying out their strategy. The German army on the Eastern Front was able to stop and even defeat the advancing Russians. On the Western Front, the German government asked permission of neutral Belgium to pass through on their way to a surprise attack on France. When the Belgians rejected the request, German troops invaded and occupied Belgium in August 1914. The Germans advanced rapidly into France but were halted by combined French and British forces miles from Paris. Both sides dug in, creating a network of opposing trenches that ultimately extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Armies on both sides would be frustrated in their attempts to break through on this “Western Front” for the next four years.

Advances in military technology caused the stalemate. The wars of the nineteenth century had been mobile, with generals coordinating the movements of infantry foot-soldiers, horse cavalry, and artillery cannons on the battle landscape. However, conflicts like the Crimean War and the U.S. Civil War had begun introducing better, more deadly weapons. Cavalry was ineffective against dug-in artillery. And in the last decades of the nineteenth century, empires had developed machine guns and then turned them on indigenous populations in territories they claimed as colonies, especially in Africa and Asia, before turning them on one another. By 1914, the armies of Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and Japan had better weapons and better defenses: long-range artillery, machine guns, trenches, and barbed wire.

Since neither cavalry nor infantry could stand against machine guns, attacks in trench warfare began with massive artillery barrages to “soften” the other side before troops were sent out of their trenches, “over the top” into the no-man’s-land between their trenches and those of the enemy, with fixed bayonets to overwhelm any enemy soldiers who had survived the shelling. When their artillery had not “softened up” the opposing forces enough, attackers would be met with enough machine gun fire to slow down any effective advance. During four long years of war, millions would either be severely wounded or killed in the “no-man’s-land” that separated the opposing armies.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Europeans on the Western Front become trapped in the trenches for four years?

- Imagine being ordered “over the top” in a charge against the enemy trench. How would you react?

Frustrated with the stalemate of trench warfare, the opposing sides on the Western Front tried new technologies and strategies in search of a decisive victory. Airplanes, first developed in 1903, proved their value in reconnaissance and later in strafing trenches with machine guns and dropping small bombs. Early radios allowed aviators to coordinate with ground controllers. And in the spring of 1915, the Germans first experimented using poison gas on the battlefield. Within months, all sides would develop different varieties of poison gas while racing to improve the designs of their gas masks. Poison gasses added another devastating weapon to trench warfare while achieving no significant advantage. At least 1.3 million people were killed by gas attacks. Tear gas, phosgene gas, chlorine gas, and mustard gas were the four most common gasses used in World War I. Tear gas was not inherently deadly but was intentionally used because it causes people exposed to behave in an erratic fashion. In the case of mustard gas poisoning, the effects took 24 hours to begin, and it could take four to five weeks to die. A lethal dose of phosgene gas exposure would result in a pulse of 120 beats per minute and coughing as the lungs produced up to two liters of discharge per hour for around 48 hours before the exposed individual eventually died from asphyxiation. German development of poisonous chlorine gas and its first use were supervised by Fritz Haber, a scientist who won the Nobel Prize for co-inventing the Haber-Bosch process for synthesizing nitrogen from the atmosphere. After 67,000 troops were killed and wounded by the gas in its first use in April 1915, Haber’s wife, the scientist Clara Immerwahr, killed herself with his service revolver in protest. Poison gases were heavier than air, so they settled into low areas like trenches but also sometimes rolled into low-lying towns, killing and injuring civilians.

Airplanes and poison gas, alongside machine guns and massive artillery, simply became more cogs in the war’s increasingly effective killing machines. More people were killed, but without any change in the outcome of the war. Enormous battles raged for months at a time at Verdun and the Somme in 1916, resulting in millions of casualties but hardly any territorial changes.

The conflict on the Eastern Front, where the Germans and Austro-Hungarians faced the Russians, was more mobile. In 1916, as the monthslong Battle of Verdun seemed to be going against the French, the Russian Army overwhelmed Austrian forces in the Brusilov Offensive, the largest and most deadly of the war. Hundreds of thousands died on both sides as the Russian army advanced, forcing the Germans to divert their forces from the Western Front. Austro-Hungarian offensive capabilities were largely destroyed, but Russian soldiers were also disillusioned and began to seriously question the competence and decisions of their officers and commanders, including the tsar himself.

World War I was global from the outset. The Japanese Empire was eager to be counted as a global power, and Japanese leaders seized upon the opportunity the war provided to improve their status in Asia. The Japanese Empire, after all, had already captured Taiwan in 1895, before they led the Eight Nation Alliance alongside European and American powers to repress the Boxer Rebellion in the late 19th century. The Japanese Empire had also defeated the Russian Empire handily during the first Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). After quickly defeating the German navy and taking control of German colonies in China and the Pacific in 1914, Japan sent the Chinese government a list of 21 demands. The Chinese believed that giving in to Japan’s demands would have basically resulted in China becoming a colony of the Japanese Empire. The Chinese government agreed to some of the demands but leaked the list to British diplomats, who intervened to prevent a complete shift in the balance of power in Asia.

In Africa, World War I was predominantly instigated by Ottoman and German campaigns in North Africa, before there were reprisals against the German colonies of Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland, German Southwest Africa (now Namibia), and German East Africa (Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania). Germany lost its colonies in the fighting. The German commanders in East Africa led a largely indigenous African force in guerrilla tactics against Allied troops for most of the war. In eastern Africa, disrupted crop cultivation led to hundreds of thousands of deaths by starvation and disease. It was uncommon to keep records of the numbers conscripted in German colonies, and thus historians have had difficulty assessing the true human cost of the war. However, the famine in areas that are now part of Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania, which was a direct result of German war policies, probably killed 300,000 civilians. However, we should also remember that the H1N1 pandemic of the “Spanish flu” was spread to sub-Saharan Africa as a direct result of European colonialist contestations, and historians have estimated that another 1.5 to 2 million people died in the pandemic in German East Africa alone.

The Ottoman Empire controlled territory on either side of the Bosporus Strait, which connects the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. In 1915, the Allies landed troops at Gallipoli, a peninsula on the European side of the Bosporus, about 200 miles (320 km) from the Ottoman capital in Istanbul. The plan was to take Istanbul, knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war, and open a third front against Austria-Hungary and Germany through the Balkans. However, the Turks held the high ground above the landing site chosen for the mostly colonial troops. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) troops were decimated in a battle that marks the beginning of a sense of nationality in those countries. The anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, April 25th, is still celebrated as ANZAC Day. The disastrous plan nearly ended the political career of the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

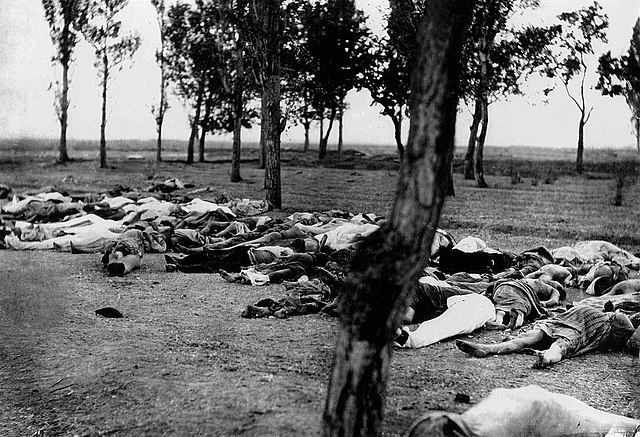

The eleven-month-long Gallipoli invasion was even more important for the Turks. The hard-fought victory was led by General Mustafa Kemal, who soon became a national hero and would go on to found the modern Turkish Republic and serve as its first president after the war. However, at nearly the same time as the Gallipoli landings, the Ottoman government also decided to take action against the Christian minority in Armenia. Armenians had suffered from periodic pogroms in the decades preceding World War I. The Armenians were loyal subjects (many were serving in the army when the persecution began), but after an unsuccessful Russian attempt to invade Turkey from the east, some military leaders in the Turkish government accused the Armenians of collaborating with the Russian troops and decided to eliminate the Armenian population. Men were executed, while women and children were force-marched across the desert to Mesopotamia. Nearly one million died in what was the worst genocide of the 20th century before the Nazi genocide of the Poles (1939–1945), the Holodomor in Ukraine and the Soviet Union (1932–1933), and the Nazi genocide of the Holocaust of World War II (1941–1945).

The imperial powers drafted soldiers from their colonies into the fight. Many of the 18 million people killed in battle and 23 million wounded were people ruled by the empires. The French brought in African troops from Senegal and Morocco, who fought and died in the trenches of the Western Front alongside other Allied soldiers. British imperial subjects like the Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders fought beside their English cousins. Over 700,000 Indians fought for Britain against the Ottomans in Mesopotamia. Indian divisions were also sent to Gallipoli, Egypt, German East Africa, and Europe. At least 74,000 Indians died in World War I.

Despite all of the efforts for a breakthrough on the battlefields of France and Eastern Europe, the most effective strategy against Germany was the British-led naval blockade, which cut off grain and other food supplies from overseas. The Germans, who had developed the most effective submarines and torpedoes, tried to blockade Great Britain and France by sinking incoming supply ships. This German naval strategy, however, risked bringing the United States into the war. After the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915, when a hundred U.S. citizens were drowned a few miles from the Irish coast, some American public opinion began to shift in favor of entering the conflict as pro-war hawks in the U.S. Congress capitalized on the deaths of passengers on the ship to argue reprisals were necessary. The German government quickly backed away from unrestricted submarine warfare against supply ships bound for Great Britain and France.

Questions for Discussion

- How did new technologies change the way war is fought?

- Why did the Gallipoli invasion almost destroy Winston Churchill’s political career?

- What motivated the Armenian genocide?

The United States had a standing policy of trying to avoid being drawn into the conflicts of the “Great Powers” of Europe. American attitudes toward international affairs reflected the advice given by President George Washington in his 1796 Farewell Address, to avoid “entangling alliances” with the Europeans. Nevertheless, the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 established the Western Hemisphere as the United States’ area of interest, implying that the U.S. only intended to interfere with European politics if they were taking place in the Americas. Of course, during the previous War of 1812, during the Spanish-American War, and the subsequent Venezuelan Crisis of 1902, the American government frequently contested with European powers, but only ever with respect to territories in the Americas or, perhaps, Asia. Indeed, after the U.S. colonization of the Philippines, the formulation of relations with Imperial Japan, and the participation of the Americans in the Eight Nation Alliance in China, it would be quite clear that American interests were not limited to the Americas. Additionally, by the 1880s and 1890s, millions of Europeans emigrated to the United States to work in factories and mines or to establish farms in the West. More Irish and Germans arrived, and also Swedes, Norwegians, Finns, Poles, Ukrainians, Italians, and Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe. Although the U.S. needed the labor base of the immigrants, their experiences differed substantially. Nevertheless, diversity among the immigrants reshaped the American political elite and helped bolster the case for U.S. neutrality in European affairs even as the war began.

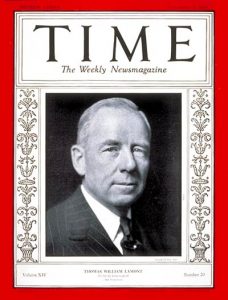

A foreign policy of neutrality also reflected America’s focus on the building of its new powerful industrial economy, financed largely with loans and investments from Europe and especially London. However, U.S. dependency on foreign capital began to change during the war, when American bankers began making substantial loans to Britain and France. John Pierpont Morgan’s successor, J. P. Morgan Jr., who had spent the early years of his career managing the family’s bank in London, leveraged a friendship with British Ambassador Cecil Spring Rice to have the Morgan bank designated as the sole-source U.S. purchasing agent for both Britain and France. J. P. Morgan and Company managed the Allies’ purchases of munitions, food, steel, chemicals, and cotton, receiving a 1% commission on all sales. Morgan led a consortium of over 2,000 banks and managed loans to the Allies that exceeded $500 million (nearly $13 billion in today’s dollars). Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan objected to the loans and argued that by denying financing to any of the belligerents, the U.S. could hasten the end of the war. But a quick end to the war was not the bankers’ goal.

J. P. Morgan and Company’s managing director, Thomas Lamont, presented his views in a 1915 speech to the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Lamont observed that the war offered the United States a unique opportunity to shift from being a debtor nation, dependent on loans from Europe and Britain, to becoming a global creditor. “We are piling up a prodigious export trade [with] war orders,” he said, “running into the hundreds of millions of dollars.” America was poised, Lamont concluded, to become the trade and finance center of the world, and the U.S. dollar would replace the British pound sterling as the world’s currency. But this would only happen, he warned, “if the war goes on long enough.” A quick end to hostilities would allow Germany to rapidly regain its competitive position. The best result for America would be a long war that ended in German defeat and left the winners deeply in debt to the United States.

Although Lamont’s prediction came true, the American economy ultimately suffered as a result of World War I. Wall Street, in New York City, became the financial capital of the world, with international debt denominated in U.S. dollars, largely because of the loans made to the European Allies during World War I. U.S. agriculture also benefited from the war raging in Europe. Armies needed calories, but the sons of farmers (and their horses) in the wheat fields of France and elsewhere were being drafted into the conflict. Soon grain from the Great Plains of the United States was feeding British and French troops on the Western Front, bringing wealth to Midwestern agricultural communities. Farmers were soon purchasing new equipment and buying or renting additional land to produce more.

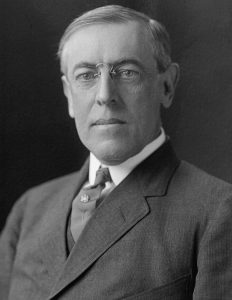

Despite Wall Street bankers’ interest in profiting from the European conflict, the U.S. federal government faced strong public opinion against entering what Americans saw as a fight they had no stake in. Scandinavians and German immigrants (the two largest immigrant groups in America) both faced public skepticism, and leaders in their communities were compelled to declare their neutrality. Germans in particular were compelled to denounce the notion that German culture was superior to that of England or France. Irish Americans, most of whom had no love of England, had gradually become a powerful force in the northern Democratic Party, dominating the big-city political “machines” in the cities of the North and Midwest. Business leaders and social activists like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, and Jane Addams were pacifists, regardless of their other political leanings. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, denounced the war in 1914 as “unnatural, unjustified, and unholy.” And socialist pamphlets argued that “a bayonet was a weapon with a worker at each end.” The antithesis to the socialists, Woodrow Wilson, ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Nevertheless, only a month after his second inauguration, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did many Americans wish to stay out of the war?

- Why did other Americans want the war to last as long as possible?

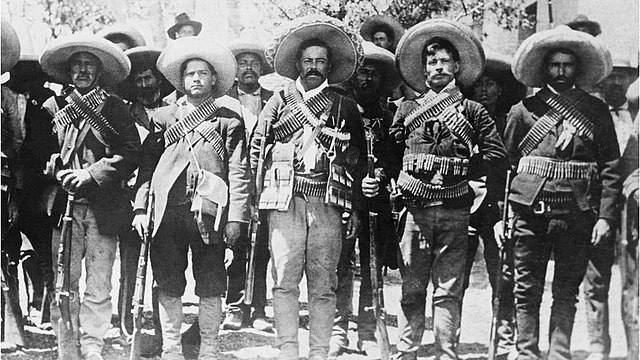

The European powers had been building up their military capabilities for nearly a generation before the outbreak of war, and it was unclear whether the United States could mobilize rapidly. In late 1916, border troubles in Mexico served as an important field test for modern American military forces and the National Guard. Revolution and chaos threatened American business interests when Mexican reformer Francisco Madero challenged Porfirio Díaz’s corrupt and unpopular conservative regime. Madero was jailed, fled to San Antonio, and planned the Mexican Revolution. Although Díaz was quickly overthrown and Madero became president, the revolution unleashed forces that demanded more social change, especially in land reform, that the new liberal government was capable of delivering. New uprisings, led by Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, broke out in rural Mexico. Reactionaries assassinated President Madero in Mexico City in early 1913, with the encouragement of the European and U.S. ambassadors, and a military regime was installed—but social upheaval and a guerrilla war continued.

In April 1914, President Wilson ordered Marines to accompany a naval escort to Veracruz on the eastern coast of Mexico. The Wilson administration had officially withdrawn its support of the new military government and watched warily as the revolution devolved into assassinations and chaos. In 1916, provoked by American support for his rivals, Pancho Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico. His troops killed seventeen Americans and burned down the town center.

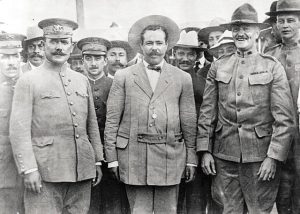

President Wilson commissioned General John “Black Jack” Pershing to capture Villa and disperse his rebels and used the powers of the new National Defense Act to mobilize over one hundred thousand National Guard soldiers from across the country as an invasion force in northern Mexico. Although these troops failed to capture Villa, they gained experience in the field and developed into a more professional fighting force that would form the basis of the U.S. Army when war was declared against the Central Powers a few months later.

In November 1916, Woodrow Wilson was re-elected president. The people rallied around the slogan “He kept us out of war.” By the spring of 1917, President Wilson became convinced by war hawks that a German victory would drastically and dangerously alter the balance of power in Europe, ultimately spelling disaster for American business. In 1917, the German general staff decided that a new push for victory on the Western Front needed to be combined with the renewal of U-boat attacks to starve the British and French. The German commanders realized their policy would draw the U.S. into the conflict on the side of the Allies but calculated that the military unpreparedness of the United States would give them time to break through the trench lines in France and end the war before the Americans arrived.

In January 1917, a document called the Zimmerman Telegram surfaced. When decoded, it was found to contain a suggestion from an official of the German foreign office to the German ambassador in Mexico that if the U.S. entered the war, Mexico should be encouraged to invade America to regain the territory taken in the Mexican-American War. Many Americans doubted the authenticity of the telegram, especially because it was delivered by British intelligence officers to the secretary of the U.S. Embassy in London. However, Zimmerman soon acknowledged its authenticity, claiming he had only been suggesting a Mexican invasion if the United States had already entered the war. The Mexican government, for its part, announced they had never seriously considered the German suggestion—after all, they were occupied with their own revolution. With American public opinion finally behind him, President Wilson went to Congress in February 1917 to announce that diplomatic relations with Germany had been severed. On April 2, Wilson returned with a “War Message” that included the argument that “the present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” Congress declared war on Germany on April 4, 1917.

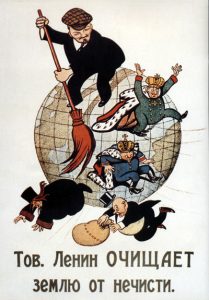

Wilson’s request for a declaration of war followed just a few days after Russia’s withdrawal from the conflict. The third year of the war saw a major change in German military prospects when the Romanov dynasty of Tsar Nicholas II collapsed in March 1917 under the weight of the February Revolution in Russia. A subsequent October Revolution placed the Bolsheviks in power, and they would withdraw Russia from the conflict. Trouble for the tsarist regime had begun in late February with a strike by women factory workers in St. Petersburg. 90,000 women took to the streets shouting “Bread!” “Down with the autocracy!” and “Stop the war!” The following day, over 150,000 men and women marched, and a general strike began. Within a few days, the army had sided with the revolutionaries, and Nicholas II was forced to abdicate.

The revolutionaries soon established a short-lived republic led by Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, which actually made it easier for U.S. President Wilson to proclaim that the war was to “make the world safe for democracy,” since a major ally was no longer ruled by an absolute monarch. However, the political and economic cost of the years of war were dire, and worker militancy in the Russian empire was at an all-time high. Furthermore, the reformist revolutionaries in Russia were not as well organized as Bolshevik revolutionaries led by Vladimir Lenin, who saw the end of tsarist rule as an opportunity to further the potential of a workers’ revolution. Peasant uprisings, after all, had become common, as had mass strikes. Parts of the provisional government supported the repression of protests in July, killing hundreds. Furthermore, the provisional government had not ended Russian participation in World War I. Lenin believed the time was ripe for the Bolsheviks to seize power while also ending Russian participation in World War I.

By the fall, the called Bolsheviks, established workers’ and soldiers’ councils—“soviets”—in the major cities. By November 1917, the failure of the provisional government to create a new constitution, end participation in World War I, or create even a modicum of reforms (such as land reform) left the Bolsheviks in control of the Russian Republic.

Lenin, confident that his revolution would soon inspire oppressed workers everywhere to overthrow capitalists and imperialists, quickly negotiated a peace with Germany in March 1918, ceding much of Russia’s western territories to the sphere of German influence, including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine, losing 34% of the former Russian Empire’s population and most of the industrial and agricultural base. However, Ukraine and Belarus would quickly join the Soviet Union. The treaty also called for territories claimed by the Ottoman Empire to be handed over to Germany’s ally, but following Lenin’s prediction, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia declared their independence instead, all eventually joining the Soviet Union. Russia also agreed to pay 6 billion marks to compensate Germany for its losses.

The Russian Revolution soon became a civil war between the “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army,” formed by the Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky, and the armies of the “White Russians” under several leaders, dedicated to restoring the tsarist monarchy. A much smaller group was an assortment of “Green armies” of armed peasant groups who were variously agrarian socialists and anarchist agrarianists—which is to say, “Leftists” but opposed to the Bolsheviks—and lived in rural areas. A small group of anarchists known as the “Black Guard” also organized in urban areas, although they were suppressed in late 1918. To prevent the return of the Romanovs to power, the revolutionaries had the entire family killed in July 1918. The revolutionaries also waged war on uncooperative peasants called Kulaks—people who were agrarian but wealthy enough to own land and hire labor—whom they accused of withholding grain from the Bolshevik government. Many of the Kulaks were Ukrainian, and some supported either the “Green” or “Black” anti-statist factions of the workers’ revolution, which contributed to an ongoing aggression toward the Ukraine by the new Soviet Union.

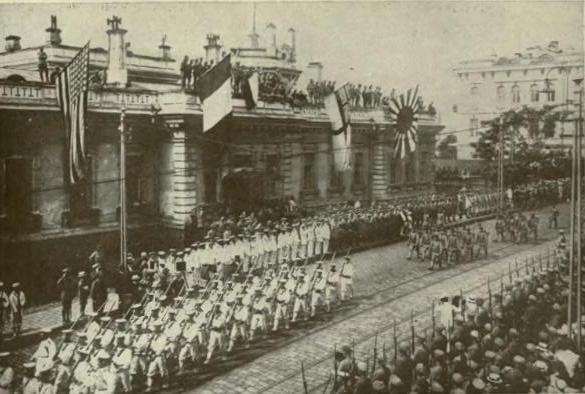

Even after World War I ended, the Allies, including the United States, supported the White Russians against the Bolsheviks, sending thousands of troops to support the counterrevolutionaries in Siberia between 1918 and 1920. Years later, the Georgian revolutionary Josef Stalin, who fought on the Bolshevik side in the civil war, would remember this fact while negotiating with Britain and the U.S. during World War II.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the Russian Revolution relate to the United States’ entry into the war?

- Why did the U.S. support the tsarist “White Russian” counterrevolution?

As soon as World War I began, governments on both sides moved quickly to portray the war effort as a success and to eliminate any sign of dissent. Britain censored mail sent by soldiers at the front to their families, instituting standardized postcards that allowed men in the trenches to choose from a menu of statements but not write anything specific about their experiences. Society became completely focused on the war effort, and governments reorganized the economy around war production. The state also rationed food and strictly controlled the media (which at the time meant the press) to silence dissent and present news of the war that boosted the morale and resolve of the population. Although British author George Orwell was still in school in England during the war, he lived through the period and later served as a military police officer in Burma. The “Orwellian” censorship and propaganda in works like 1984 probably reflect his experience during the First World War and later, as his democratic socialist politics rejected authoritarianism.

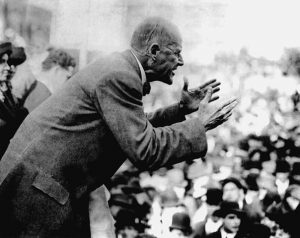

To stifle dissent in the U.S., Woodrow Wilson’s administration signed the Espionage Act into law in 1917, which was designed to prosecute those who had “poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life…to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue.” Although Wilson implied that the people he intended to target were “born under other flags,” most of the people prosecuted, like labor leader and Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, were American citizens. Indeed, most were American leftists. Wilson also suggested that labor unions’ actions to defend worker rights during wartime would be considered an attack on America. The law was expanded with the Sedition Act of 1918, which prohibited any forms of speech that could be considered “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.” As the Russian Revolution was taken over by the Bolsheviks, U.S. concern shifted from draft resistance to socialism, and the First Red Scare gripped America. Hundreds were arrested, deported, and jailed under the Espionage and Sedition Acts. By 1919, even the authorities realized they had gone too far, and the U.S. attorney general convinced President Wilson to commute the sentences of 200 prisoners convicted under the acts.

In their attempt to repress leftists during World War I, domestic politics turned increasingly authoritarian among the Allied powers of Britain, France, and the U.S. Yet, seemingly paradoxically, opportunities for women’s advancement in society improved. Women on all sides served as nurses and medics and worked in agriculture and industry to keep the economy going while men were away fighting. Some women, such as a Sergeant Sandes, who was at first a British nurse but later fought in the Serbian Army, even fought on the front lines. Many governments promised equal pay, although most did not make good on their promise. But women gained political influence and achieved the right to vote in the U.S. and a few European countries almost immediately after the war’s end as a result of their contributions to the war effort. Furthermore, women gained increases in rights in the Russian Republic (1917–1918) and the subsequent Soviet Union as a result of the state making good on some promises of socialist ideology in the arena of gender equity.

Questions for Discussion

- What did it take for the American people to support U.S. entry into the war?

- How did the ongoing Russian Revolution and the growing prominence of the Bolsheviks influence U.S. government policy?

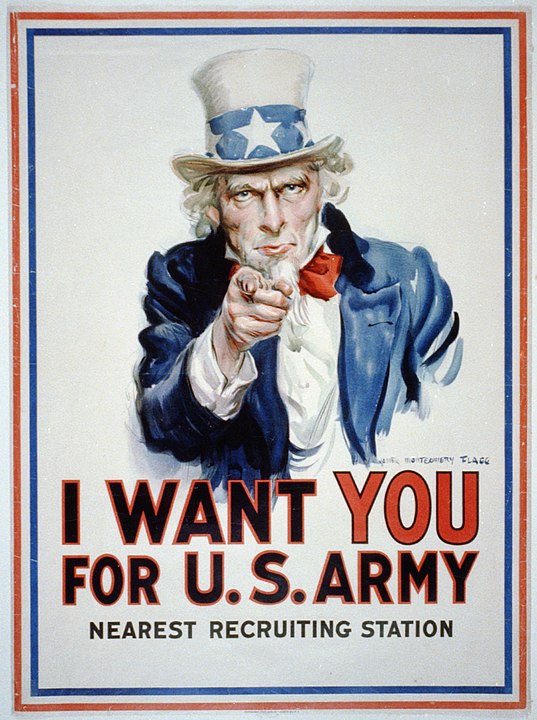

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war, with its advanced artillery, machine guns, poison gas, and submarines. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against German submarine attacks, which had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although many of the supplies still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to be a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

In March 1918, Germany tried to take advantage of the withdrawal of Russia and its new single-front war before the Americans arrived with the Kaiserschlacht (Spring Offensive), a series of five major attacks. By the middle of July 1918, each and every one had failed to break through the Western Front.

Then, on August 8, 1918, two million men of the American Expeditionary Forces joined the British and French armies in a series of successful counteroffensives that pushed the disintegrating German lines back across France. The gamble of the Spring Offensive had exhausted Germany’s military, making defeat inevitable. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated at the request of the German military leaders, and a new democratic government agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918, hoping that by embracing Wilson’s call for democracy, Germany would be treated more fairly in the peace talks. German military forces withdrew from France and Belgium and returned to a Germany teetering on the brink of chaos. November 11 is still commemorated by the Allies as Armistice Day (called Veterans’ Day in the United States).

In all, between 16 and 19 million soldiers died in World War I, along with 7 to 8 million civilians (not taking into account the H1N1 “Spanish flu” pandemic that lasted from as early as 1916 to as late as 1920). Some of the worst battles were:

- Verdun: 976,000 casualties (Feb.–Dec. 1916)

- Brusilov Offensive: Nearly 2,000,000 casualties (June–Sept. 1916)

- Somme: 1,219,201 casualties (July–Nov. 1916)

- Passchendaele: 848,614 casualties (July–Nov. 1917)

- Spring Offensive: 1,539,715 casualties (March 1918)

- 100 Days Offensive: 1,855,369 casualties (Aug.–Nov. 1918)

Civilian populations were also targeted. While bombing cities from airplanes was much more common in World War II, naval blockades were also an effective way of putting pressure on civilians. Even if a nation was relatively self-sufficient in food production under normal circumstances, war was not a normal circumstance. The British blockade of Germany prevented not only war supplies but food from reaching the German people, resulting in a half million civilian deaths. For the Europeans, World War I was a “Total War” involving every level of society.

By the end of the war, more than 4.7 million American men had served in all branches of the military. The United States lost over one hundred thousand men, fifty-three thousand dying in battle and even more from disease. Their terrible sacrifice, however, paled before the European death toll. After four years of stalemate and brutal trench warfare, France had suffered almost a million and a half military dead and Germany even more. Both nations lost about 4 percent of their populations to the war. And death was not nearly done.

Questions for Discussion

- What effects do you think the trenches and poison gas attacks had on European soldiers and civilians?

- Why did Germany throw so much into the Spring Offensive?

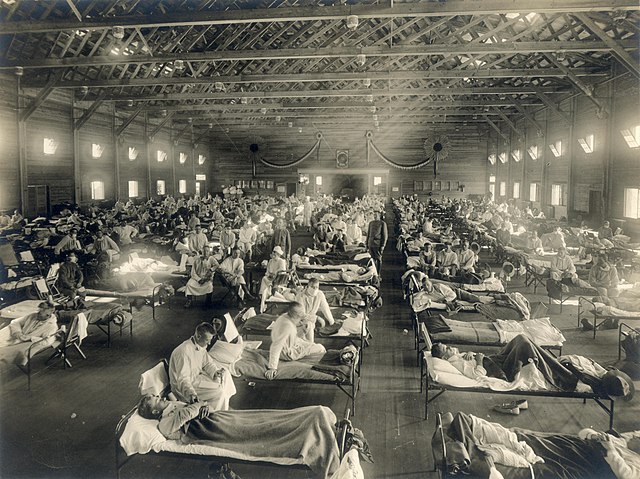

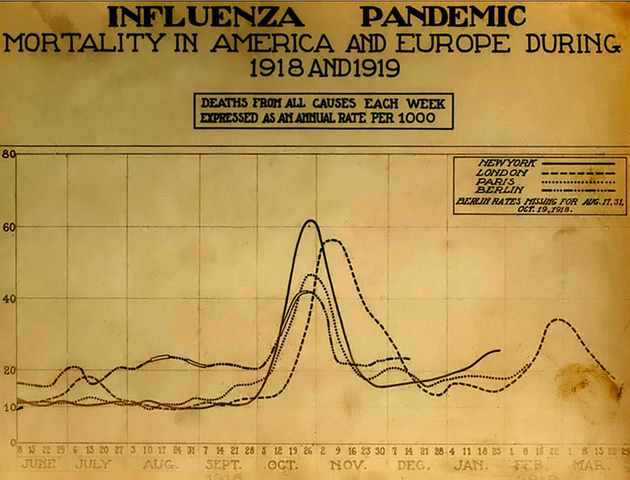

Even as war raged on the Western Front, an even deadlier threat loomed. In the spring of 1918, a new strain (H1N1) of the influenza virus was documented for the first time in the farm country of Kansas and hit nearby Camp Funston, one of the largest army training camps in the nation. The virus spread like wildfire. Between March and May 1918, fourteen of the largest American military training camps reported outbreaks of influenza. Some of the infected soldiers carried the virus on troop transports to France. By September 1918, influenza had spread to all training camps in the United States.

The second wave of the virus was even deadlier than the first because people refused to adhere to public health measures designed to prevent the spread of the disease, especially in urban areas. Unlike most flu viruses, the H1N1 strain struck down those in the prime of their lives rather than old people and young children. A disproportionate number of influenza victims were between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five. In Europe, influenza hit troops and civilians on both sides of the Western Front. The disease was misnamed “Spanish influenza” in English due to the fact that the newspapers of neutral Spain were among the few sources that openly published about the disease. Both America and Britain suppressed accounts of the disease in their press, as did France and Germany.

The “Spanish flu” infected about 500 million people worldwide and resulted in the deaths of between fifty and a hundred million people, possibly more. Furthermore, subsequent research has detailed that the disease could have appeared in the H1N1 variant as early as 1916 and almost certainly lasted until 1920, or perhaps even later. World population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion; influenza infected nearly a third and killed between 5% and 10%. Reports from the surgeon general of the army revealed that while 227,000 American soldiers had been hospitalized from wounds received in battle, almost half a million suffered from influenza. The worst part of the wartime pandemic struck during the height of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918 and weakened the combat capabilities of both the American and German armies. Furthermore, because of the global nature of the conflict, the disease spread among armies on all continents. During the war, more soldiers died from influenza than combat. But the pandemic continued to spread after the armistice, with a death toll of nearly 20% of those infected as opposed to about 0.1% in regular flu epidemics. Four waves of worldwide infection spread before cases and deaths finally began fading in April 1920. No cure was ever found, and the same virus (H1N1) caused one subsequent epidemic (the 1977 Russian flu) and one subsequent pandemic (the 2009 swine flu), although both the latter epidemic and pandemic were substantially less deadly.

Questions for Discussion

- Compare the “Spanish flu” with the current COVID-19 pandemic. What can we learn from the past?

On December 4, 1918, President Wilson became the first American president to travel overseas while in office. Wilson went to Europe to end “the war to end wars,” and he intended to shape the peace. As part of the armistice, Allied forces occupied territories in the Rhineland separating Germany and France to prevent conflicts there from reigniting war. A new German government disarmed while Wilson and other Allied leaders gathered in France at Versailles to dictate the terms of a settlement to the war. After months of deliberation, the Treaty of Versailles officially ended the war.

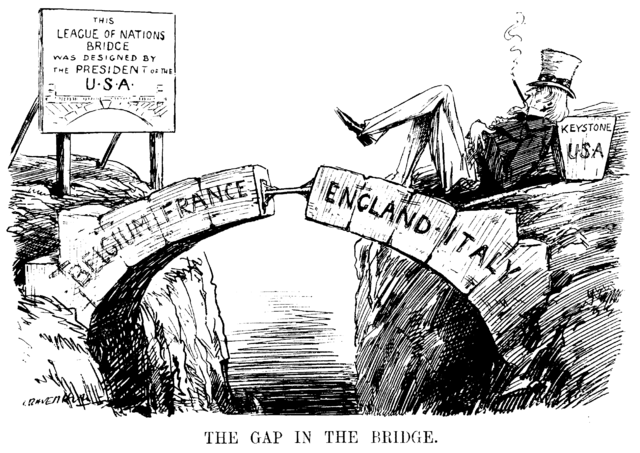

In January 1918, before American troops had even arrived in Europe, President Wilson had offered an ambitious statement of war aims and peace terms known as the Fourteen Points to a joint session of Congress. Wilson called for reductions in armaments, freedom of the seas, adjustment of colonial claims, and the abolition of the types of secret treaties that had led to the war. However, in January 1918, Germany still anticipated a favorable verdict on the battlefield and did not seriously consider accepting the terms of the Fourteen Points, and the Allies were dismissive. French prime minister Georges Clemenceau remarked, “The good Lord only had ten [commandments].” Nonetheless, Wilson aimed to expand American power “to make the world safe for democracy.” At the center of the plan was a new international organization, the League of Nations. It would be charged with keeping a worldwide peace, “affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” This promise of collective security, that an attack on one sovereign member would be viewed as an attack on all, was a key component of the Fourteen Points. Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech was translated into many languages and was even sent to Germany to encourage negotiation.

Despite the Allies’ lack of agreement with the Fourteen Points, the key role of U.S. troops and U.S. dollars in the outcome gave the Americans an influential seat at the negotiating table at Versailles. Wilson’s appointee, Thomas Lamont, became a central figure in the negotiations that ended the war and set guidelines for German reparations that ultimately bankrupted the nation and led to World War II. Britain and France were successful in getting the punitive items they wanted into the final treaty. Lamont went along because shifting the financial burden to Germany guaranteed that the Allied nations that owed J. P. Morgan and Company so much money would be able to pay it back.

By June 1920, the final version of the treaty was signed, which centered upon a compromise that included demands for German reparations, provisions for the League of Nations, and the promise of collective security. According to historian Ferdinand Lundberg, the “total wartime expenditure of the United States government from April 6, 1917, to October 31, 1919, when the last contingent of troops returned from Europe, was $35,413,000,000. Net corporation profits for the period January 1, 1916, to July 1921, when wartime industrial activity was finally liquidated, were $38,000,000,000.” In the years after the war, J. P. Morgan and Company would earn additional millions loaning Germany the money the treaty required it to pay to the Allies so they could pay the bankers.

Questions for Discussion

- Do you see any difficulty with the idea that Woodrow Wilson is typically seen by historians as an idealist, but his chief negotiator at Versailles was Thomas Lamont?

- Were Europeans right or wrong to put their national concerns first?

- In your opinion, what was the point of the League of Nations? As Wilson had imagined it, who did it benefit?

- Was the United States right or wrong to stay out of the League?

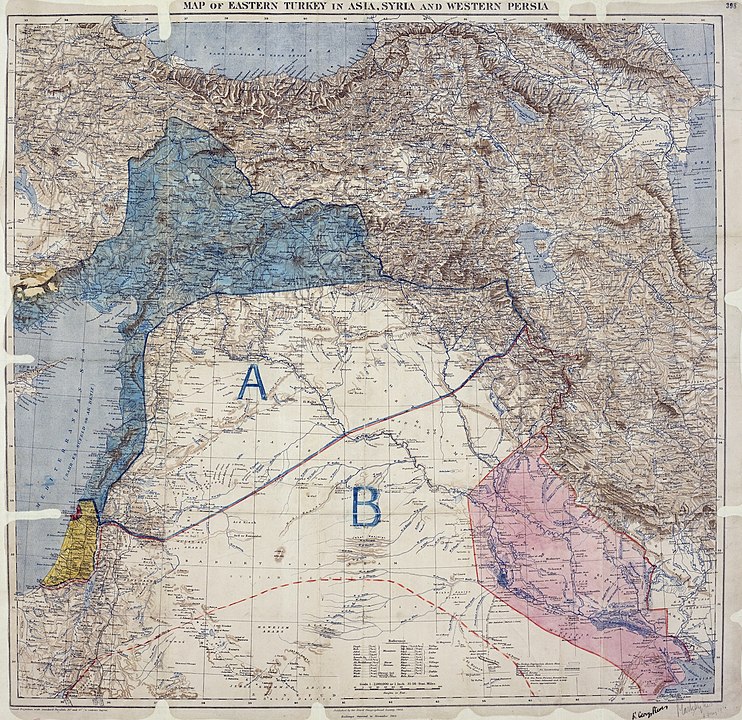

Southwestern Asia and North Africa were drastically changed by World War I. Before the war, the region east of the Mediterranean had three main centers of power: the Ottoman Empire, the British Egypt, and Iran. In the aftermath of the war, Wilson sent the King-Crane Commission to determine the conditions and aspirations of people in Southwestern Asia, which found that most favored an independent state free of European control. However, the people’s wishes were largely ignored, and the lands of the former Ottoman Empire were divided into several nations created by Great Britain and France with little regard to ethno-nationalist divisions. The British in particular wanted to continue to control the Suez Canal, which was their route to India, and monopolize the oil of the Persian Gulf to fuel the diesel engines of their navy and merchant marine.

The Arab provinces of the Ottomans were to be ruled by Britain and France as “mandates,” and a new nation of Turkey emerged in the former Ottoman heartland in Anatolia. According to the League of Nations, mandates were necessary in regions that “were inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world.” Though supposedly established for the benefit of the Middle Eastern people, the mandate system was essentially a reimagined form of nineteenth-century imperialism. France received Syria (and Lebanon); Britain took control of Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan (Jordan).

To consolidate their power over the Arabs, the British supported Hussein Ibn Ali as king of Hejaz on the Arabian Peninsula, including the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, in 1916. His sons, Abdullah and Faisal, were chosen to be kings of Transjordan and of Syria, where Faisal was rejected and so instead became the king of Iraq. Although the Iraqi dynasty ended with the murder of Faisal’s grandson in 1958 during the Iraqi July 14 Revolution, Abdullah’s dynasty still rules Jordan under Abdullah II and Queen Rania. In the Hejaz, Hussein Ibn Ali was overthrown in 1925 by Ibn Saud, the son of the last Emir of Nejd, the much larger portion of what is now Saudi Arabia. Through strategic marriages with other royal families, Ibn Saud established Saudi Arabia. He had so many children that the current king is still one of his many sons.

The disposition of the Southwestern Asia was complicated by the increasing importance of its oil resources. Oil had been discovered in Iran in 1908, and during the period when petroleum was becoming the most important commodity of the twentieth century, it was also becoming clear that some of the world’s largest reserves were located in the Middle East. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now known as BP) was established in 1908 to control production in Iran. After the war, British-controlled businesses that had been licensed by the Ottomans to develop oil discovered in Mesopotamia spurred British interest in creating the new Kingdom of Iraq under British mandate in 1920. The British-controlled multinational TPC (Turkish Petroleum Company, established in 1912) received a 75-year concession to develop Iraq’s oil.

However, in 1933, when enormous deposits of oil were discovered in eastern Arabia, Ibn Saud turned to the Americans rather than the British to exploit these oil deposits, fearing renewed British meddling in his country. U.S. oil companies have been there ever since.

The movement to establish a Jewish homeland—Zionism—was begun in the 1890s by Jewish Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl. Shocked by how Jews were being persecuted throughout Europe, even in liberal France, Herzl concluded that Jews would never be fully accepted as citizens anywhere and that they needed to establish a separate Jewish homeland. After some debate, his movement decided to begin buying land in Palestine, the site of the ancient Hebrew kingdom. Originally, most Jews around the world, especially more religious Jews, rejected the movement because they believed that Jews were not to return to Israel until the Messiah came. Zionists in Palestine often also had problems with their Palestinian Arab neighbors, who looked upon these new arrivals as Europeans trying to take over their country.

In the heat of the war, in 1917, the British foreign secretary Lord Balfour promised that Palestine would be recognized as a “Jewish homeland” in an attempt to gain support of Jews among the belligerents—not realizing that Zionism was hardly the majority view at that time within Judaism. It is of note that Lord Balfour had previously supported the establishment of immigration restrictions upon Ashkenazim Jews of Eastern Europe to prevent them from entering Britain. Many would later criticize him for supporting a Jewish Palestine because it meant there would be fewer Jews in Britain itself. Of course, the British officials also promised to respect Arab sovereignty in Palestine, setting the stage for conflict in the region that has continued to today.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the negotiations between European powers set the scene for the conflicts of the following century?

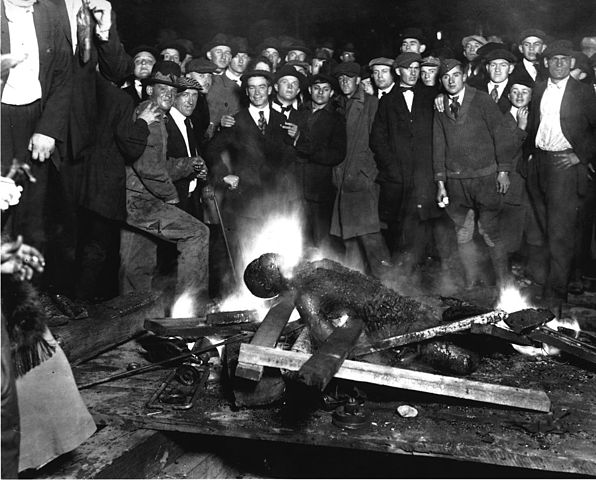

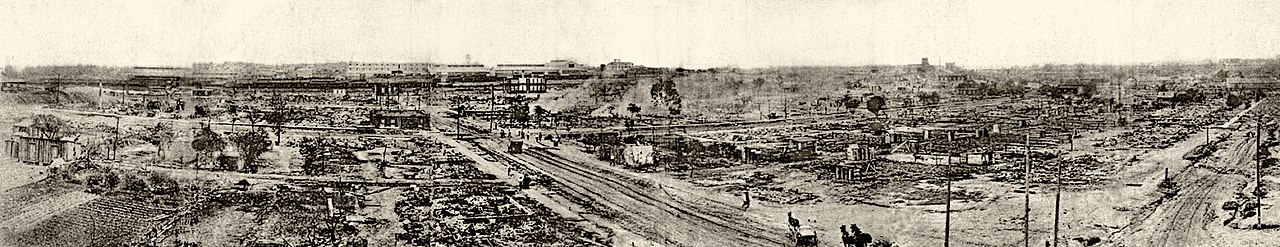

At home, the United States grappled with harsh postwar realities. Racial tensions exploded in the “Red Summer” of 1919, when violence broke out in at least twenty-five American cities, including Chicago and Washington, D.C. Industrial war production and massive wartime service had created vast labor shortages, and thousands of black southerners had traveled to the North and Midwest to work in factories. In fact, the “Red Summer” was part of a much larger wave of white supremacist mob violence that occurred from the 1880s through the 1930s. Lynching was common, and victims were overwhelmingly Black. However, occasionally, southern Italians (Sicilians) were also lynched, often targeted based on the racist assumption that they were part African. Chinese American communities were targeted and had experienced waves of violence in the 1890s. Additionally, in the Southwest, including Texas, along the border with Mexico, most of the victims were Latinx/Hispanos. Native Americans were also murdered by white supremacists during the same period. But the most violent massacre occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when city officials deputized and armed a mob of white supremacists to attack and destroy the Greenwood District on the night of May 31–June 1, 1921. Greenwood had been one of the most prosperous Black neighborhoods in America and was even called “Black Wallstreet,” but it was reduced to rubble. A 2001 commission estimated 150–300 Black civilians were murdered by the mob, 800 were admitted to hospitals, and some 6,000 Black residents were interned in large temporary prison camps. Untold numbers (thousands) were displaced. The Greenwood neighborhood did defend itself, however, and exacted a toll of 50 deaths from the mob of white supremacists that attacked them.

Many Black Americans who had fled white supremacy in the South or had traveled halfway around the world to fight for the United States would not so easily accept postwar racism. The overseas experience of Black Americans and their return triggered a dramatic change in their home communities. W. E. B. Du Bois, a black scholar and author who had encouraged blacks to enlist, highlighted African American soldiers’ combat experience when he wrote of returning troops, “We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy!” But white Americans just wanted a return to the status quo, a world that did not include social, political, or economic equality for black people. And they were alarmed and frightened by the thought of fearless, capable black men who had learned to handle weapons and defend themselves on foreign battlefields.

In 1919, so-called racist riots erupted across the country from April until October. Retrospectively, we might term these pogrom, drawing from a Russian-language term that describes a form of state-endorsed informal mob violence that is used to target ethnic or religious minority communities. The bloodshed included thousands of injuries, hundreds of deaths, and vast destruction of private and public property across the nation. The weeklong “Chicago Riot,” from July 27 to August 3, 1919, considered the summer’s worst, included mob violence, murder, and arson. “Race riots” had rocked the nation before, as previously mentioned, but the Red Summer was something new. Recently empowered black Americans actively defended their families and homes from hostile white rioters, often with militant force. This behavior galvanized many in black communities, but it also shocked white Americans who interpreted black self-defense as a prelude to total revolution. In the riots’ aftermath, James Weldon Johnson wrote, “Can’t they understand that the more Negroes they outrage, the more determined the whole race becomes to secure the full rights and privileges of freemen?” In the fall, an organization called the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) formed in northern cities as a permanent “armed resistance” movement. The socialist orientation of its members rapidly led to an affiliation with the Communist Party of America. But the Russian-led Communist International (Comintern) had no interest in semi-independent groups like the ABB with their Afro-Marxist ideas. The Brotherhood’s members found their way to other organizations like the Workers Party of America and the American Negro Labor Congress.

The wave of widespread lynching and riots against African Americans lasted into the early 1920s. Many white Americans claimed they “felt threatened” by African American success and increased social mobility. The early 1920s also saw a resurgence of the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which now added immigrant Jews and Catholics to the list of those who would destroy “traditional” white Protestant America. They infiltrated both political parties, and affiliated groups were especially tied to the Republican Party in northern states, such as Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, where a split-off of the KKK eventually became known as the “Black Legion” in the 1930s. White supremacist ideas culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which lowered overall immigration to a small fraction of what it was before World War I while setting up a quota system based on the ethnic makeup in the U.S. in 1890, a time before many Jewish and Catholic immigrants arrived from southern and eastern Europe.

The desire to rid the United States of what the majority perceived as evil is also seen in the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in the U.S. Liquor had ruined many American families, and women in particular had suffered as abused spouses. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union and similar prohibitionist organizations were prominent in the Progressive Era, pushing for a federal graduated income tax to replace the lucrative tax on liquor. The war made prohibition even more patriotic, since the beer industry was dominated by immigrant Germans, and the amendment was ratified shortly after the end of the war.

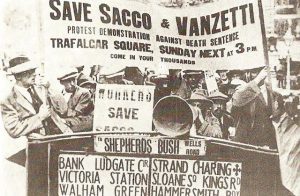

The success of the Russian Revolution and the Communist victory in the Russian Civil War enflamed American fears of communism. The executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian-born anarchists, epitomized the new American Red Scare. Arrested on suspicion of armed robbery and murder, their trial focused not on the defendants’ guilt or innocence but on their anarchist political affiliations. Sacco and Vanzetti were quickly convicted and sentenced to death, setting off a series of appeals and motions for mistrial. In 1925, while the two men sat on death row, another man confessed to the crime and provided details that made his confession credible. The judge, however, refused a petition for a new trial, later remarking to a Massachusetts lawyer, “Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?”

People all over the world demonstrated their sympathy with the accused. Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw, and H. G. Wells signed petitions. Demonstrations were held in London, Paris, Geneva, Amsterdam, and Tokyo. Famous authors wrote about the case, such as John Dos Passos’s Facing the Chair, Maxwell Anderson’s Gods of the Lightning, and Upton Sinclair’s Boston. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union called a three-day national walkout to protest the executions. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed just after midnight on August 23, 1927. The Sacco-Vanzetti case demonstrated an American paranoia about immigrants and the potential spread of radical ideas, especially those related to international communism. On the 50th anniversary of the executions, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that “any disgrace should be forever removed from their names.”

Questions for Discussion

- What did the extension of racial conflict into the North after the war suggest about American attitudes regarding race?

- Was the anxiety of the Red Scare justified? Why were Americans so afraid of communism in the early 1920s?

Media Attributions

- Periscope_rifle_Gallipoli_1915 © Ernest Brooks is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Map_Europe_alliances_1914-en.svg © historicair is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Kaiser_Wilhelm_II_of_Germany_-_1902 © T.Voigt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Balkan_troubles1 © Leonard Raven-Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- DC-1914-27-d-Sarajevo-cropped © Achille Beltrame is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_War_of_the_Nations_WW1_337 © O Suave Gigante is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- German_soldiers_in_a_railroad_car_on_the_way_to_the_front_during_early_World_War_I,_taken_in_19 14._Taken_from_greatwar.nl_site © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bundesarchiv_Bild_136-B0560,_Frankreich,_Kavalleri sten_im_Schützengraben © Oscar Tellgmann is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Aerial_view_Loos-Hulluch_trench_system_July_1917 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FirstSerbianArmedPlane1915 © Museum of Yugoslav Aviation is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nach_Gasangriff_1917 © Hermann Rex is licensed under a Public Domain license

- В_атаку!_(1916) © штабс-капитан is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Battle_of_Tsingtao_Japanese_Landing © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Scene_just_before_the_evacuation_at_Anzac._Austral ian_troops_charging_near_a_Turkish_trench._When_they_got_there_the…_-_NARA_-_533108.tif © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ambassador_Morgenthau’s_Story_p314 © Henry Morgenthau is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Indian_bicycle_troops_Somme_1916_IWM_Q_3983 © John Warwick Brooke is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Noordam-delegates-1915 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- J.P._Morgan_and_J.P._Morgan_Jr © Moody’s Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pacifists_at_Capitol_LOC_16992358889 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pancho_and_his_followers © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gen_Obregon,_Villa,_Pershing_at_Ft_Bliss_1914 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Woodrow_Wilson-H&E © Harris & Ewing is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Russian_Troops_NGM-v31-p379 © George H. Mewes is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tov_lenin_ochishchaet © Viktor Deni is licensed under a Public Domain license

- IntervenciónInternacionalEnVladivostok–throughrussi anre00willuoft © Albert Rhys Williams is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Debs_Canton_1918_large © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Uncle_sam_propaganda_in_ww1 © James Montgomery Flagg is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Western_front_Kaiser_in_trench_1918-04-04 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emergency_hospital_during_Influenza_epidemic,_Camp_Funston,_Kansas_-_NCP_1603 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Spanish_flu_death_chart © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Woodrow_Wilson_returning_from_the_Versailles_Peace_Conference_(1919) © Associated Press is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Gap_in_the_Bridge © Leonard Raven-Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ThomasWLamont-1929Timemagazine © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MPK1-426_Sykes_Picot_Agreement_Map_signed_8_ May_1916 © Royal Geographical Society is licensed under a Public Domain license

- King_Faisal_I_of_Syria_with_King_Abdul-Aziz_of_Saudi_Arabia_in_the_mid-1920s © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PikiWiki_Israel_7188_Herzl_on_board_reaching_the_ shores_of_Palestine © מידע אין is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Omaha_courthouse_lynching © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ChicagoRaceRiot_1919_wagon © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Panorama_of_the_ruined_area_tulsa_race_riots_(retouched) © Mary E. Jones Parrish is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Save_Sacco_and_Vanzetti © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license