11 Cold War

The Cold in Europe and the Soviet Union

When Americans think of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, they typically think of thousands of nuclear missiles controlled by Moscow and Washington, D.C., pointed at one another. Alternatively, they might imagine an ideological conflict of the capitalist First World and communist Second World engaged in a battle for global supremacy. They also often assume there was no “hot war.” Any understanding of a violent confrontation between 1945 and 1991 is reduced to the terms of “proxy conflicts.” This understanding argues neither the U.S. nor the U.S.S.R. launched direct attacks on one another but rather intervened in regional conflicts, attempting to gain influence. This U.S.-centered understanding of the Cold War is a myth. It is a myth not just because it mischaracterizes post–World War II liberation struggles as “proxy conflicts” but also because it ignores the history of most of the world’s population. The governments representing most of the world’s population between 1945 and 1991 were not divided between Soviet and American allegiance; rather, they sought to create a Non-Aligned Movement, characterized by opposition to all forms of colonialism and neo-colonialism as well as a rejection of the imposition of either First or Second World alignment. American or Soviet politicians might have argued in favor of buffer zones, defending like-minded governments, or simply protecting economic interests, aptly accusing one-another of imperialist ambitions. Yet from 1945 onward, this “Third World” also clamored for self-determination.

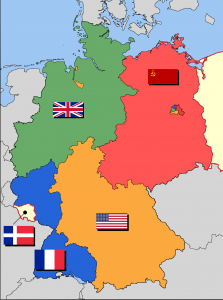

Toward the close of WWII in February 1945, Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill met at Yalta, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea. While Roosevelt desired Soviet participation in the invasion of Japan and Soviet membership in the United Nations, Churchill aimed for free elections in Central and Eastern Europe (especially Poland), and Stalin aimed for recognition of Soviet influence over Central and Eastern Europe. To resolve the dispute, Stalin pledged an invasion of Japan three months after a German surrender and elections could be held in Eastern Europe if the Soviets were to be granted Eastern Europe as part of their recognized sphere of influence. All parties agreed that Nazi war criminals would be tried in the territories where their crimes were committed, and Nazi leadership would be executed. Finally, a partition agreement was drafted. Germany was divided into four zones, as Stalin acquiesced to the proposal to grant France a zone separate from the Soviet, British, and American zones, so long as it was carved from the British and American zones. The partition foreshadowed contestations between American and Soviet politicians for influence in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia for the next five decades.

Although Stalin had promised elections in Eastern Europe, he had not guaranteed the results would match the dreams of Churchill and Roosevelt. Multi-party elections were held. Yet, in Romania, the Communist Party allied with other left-wing groups to secure a victory of the “Democratic Bloc” with nearly 70% of the vote in the 1946 election. In 1947, a similar “Democratic Bloc” secured 80% of the votes in the Polish elections, with the communist Polish Workers Party at the helm and amid widespread Soviet repression of Polish citizens, which had occurred from 1939 to 1946. Consolidation into political blocs, or “fronts,” would prove an effective means to establish almost absolute political control for communist parties in Eastern Europe, as would outright revolution.

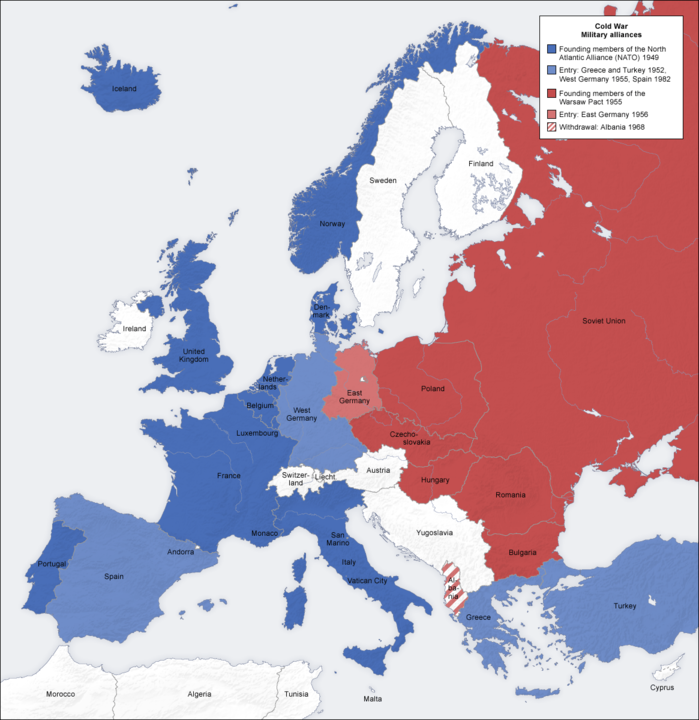

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia mounted a coup d’état, eliminating right-wing opposition groups in the country, including fascists and fascist sympathizers. The vehicle for their control was not a Communist Party but rather a coalition: the National Front of Czechs and Slovaks secured 89% of control in the 1948 elections. A similar “National Independence Front” formed an alliance between the Hungarian Communist and Social Democratic Parties and won 97% of the vote in the 1949 election. After the elimination of right-wing—most often openly fascist or fascist-sympathizing—parties across Eastern Europe from 1946 to 1948, left-wing parties consolidated into political blocs, gradually resulting in de facto, but not actual, single-party states. For example, in the Bulgarian election of 1949, the “Father Front” that took 99.8% of the vote was an alliance of three parties: the Social Democratic Workers Party, the Agrarian National Union, and the Bulgarian Communist Party. Front and bloc consolidation secured Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Bulgaria as part of the Soviet sphere through 1989, and together, they would become members of the Warsaw Pact in 1955 as a response to the expansion of NATO’s (f. 1949) expansion to include West Germany (Feder Republic of Germany, BRD).

Stalin’s desire for control in Eastern Europe could be explained by the desire to create a buffer zone to prevent a Western European invasion of Russia. After all, Napoleonic France had invaded Russia in the 19th century and Nazi Germany had invaded again in the 20th century. Yet, the very desire of Eastern Europeans for the creation of an alternative society to the totalitarian imperial opulence that had dominated Eastern Europe up until the threat of fascism was also a motivating factor. Indeed, communists and socialist partisans were often first to die in the fight against fascism in Europe. Officially, Moscow held that 20 million Soviet civilians and military personnel had died in the fight against fascism, although historians have argued the numbers were even higher. Another Communist Party–controlled nation, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, headed by the famed anti-fascist partisan revolutionary, Josip Broz Tito, posed the first challenge to Stalin’s imaginaire of a unified Eastern Europe.

In 1945, Tito’s Socialist Alliance of Working People of Yugoslavia secured 90% of the vote. In 1946, the Yugoslav government submitted a claim of 1,706,000 civilian and military dead to the International Reparations Commission in Paris. Although the number was later revised by historians down to around 1 million, the losses still represented much more substantial devastation than those faced by France, the United Kingdom, or the United States. By 1947, it was clear that Tito aimed to expand Yugoslavia southward to include Albania and a portion of Greece. Yugoslav communists also argued they needed access to Bulgarian bases to support the Greek communists in the Greek Civil War (1943–1949). However, Stalin vetoed the potential Bulgarian-Yugoslav agreement. Tito and Stalin thus parted ways from 1948 onward. Without Tito, there would never be such an organization as a “unified Soviet aligned Eastern Europe,” as both Moscow and Washington imagined. Instead, seven years after the 1955 Bandung Conference was held in Indonesia, Tito would establish the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) with leadership from India, Egypt, Indonesia, and Ghana at a conference in Belgrade in 1961.

As fascist forces retreated from North Africa, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region from 1944 through 1945, the British and French Empires also began to collapse. From Asia to Africa to Europe, contestations over the future of nations emerged. Lebanon (1943), Syria (1945), and Vietnam (1945) all declared independence from France, resulting in violent conflicts over the future of their peoples. Indonesia declared independence from the Netherlands in 1945. The Philippines was a founding member of the United Nations in 1945, although the U.S. would not recognize independence until 1946. In Greece, British and American backing slowly brought victory to the Greek monarchy, which had been in exile since the 1941 fascist invasion. Cold War–era threats to peace began with the Greek Civil War (1943–1949) along with the Partition of Israel-Palestine (1947) and the Partition of India-Pakistan (1947). All three represented different types of failures of the new international order to prevent mass violence. In the Greek Civil War, the Allied British and American forces would back an attempted return of the monarchy. General Secretary Nikolaos Zachariadis, the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and their militant wing, the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE), viewed the monarchy, naturally, as tyrannical. They proclaimed a separate government in December 1947. But at the height of their power in 1948, the Soviet-Yugoslav split resulted in the withdrawal of Soviet support from Greece. By 1949, Alexandros Papagos’s brutal authoritarian tactics, utilizing threat, execution, and prison camp labor for supporting communists, crushed all remaining support for the DSE in the countryside.

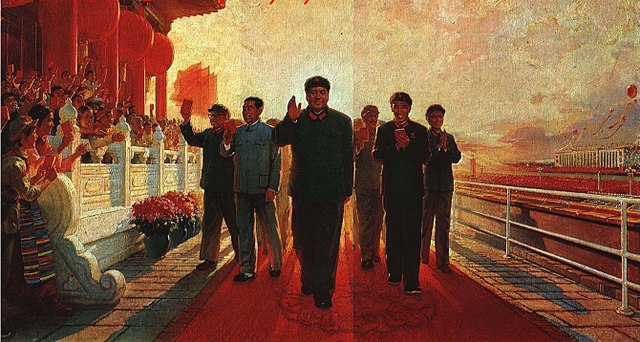

In Washington, the victory of Papagos’s forces was touted as an example of the Truman Doctrine in action. After all, Truman had pledged “containment,” meaning a commitment to help end communist uprisings in Greece and Turkey without the direct use of American troops. Thus, American politicians aimed to stop the expansion of “Iron Curtain,” per Churchill’s description to Roosevelt of Stalin’s influence in Eastern Europe. The irony was, by the end of the Greek Civil War in October 1949, another much more significant, protracted, and bloody civil war had just ended. With the proclamation of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China by Mao Zedong in Tiananmen Square also in October 1949, a much more significant country had been established as potentially Soviet aligned. Hence, Cold War hawks in Washington would begin to discuss containment as preventing the expansion of a similar “Bamboo Curtain” in Asia.

Yet the Truman Doctrine of containment objectively failed in many locations, such as Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. In the locations where it succeeded, such as Iran (for a time) Greece, Brazil, Guatemala, and Indonesia, “success” came at the cost of backing tyrannical, authoritarian, and sometimes genocidal regimes. In Europe, the division of Germany was completed in October 194. The division consisted of the western Federal Republic of Germany (BDR) and the eastern German Democratic Republic (DDR). While the government of the BDR prided itself on multi-party elections, the government of the DDR prided itself on social welfare reforms. Elections were conducted in the DDR, but political parties were consolidated under a single “front,” much like the rest of Eastern Europe. However, both kept Nazi-era discriminatory laws on the books, such as the infamous “Paragraph 175,” which criminalized homosexuality. The law was partially abrogated in the GDR in 1950, and further restrictions were eased in 1968, prompting the DDR to ease restrictions on “Paragraph 175” in 1969.

American animosity toward Moscow was deeply rooted. The First Red Scare in the United States occurred amid the backlash of business elite against the success of the 1917 revolution. The British-American-Soviet allegiance during World War II was more of an interlude, an anomaly of practicality, and not a natural world order. Already in February 1947, George Kennan—head of the U.S. embassy in Moscow—sent “The Long Telegram” to the State Department denouncing the Soviet Union. Kennan’s main point was that the Soviet Union was interested in expanding power worldwide, but he formulated his argument as an attack on communism rather than Soviet power. “World communism is like a malignant parasite which feeds only on diseased tissue,” Kennan wrote, and “the steady advance of uneasy Russian nationalism… is more dangerous and insidious than ever before.” For him, Russian imperialism had not ended with the Russian Empire; it simply transformed under the “new guise of international Marxism.” Yet a debate in the Soviet Union that had occurred in the 1920s had already split Soviet communists between the camps of the so-called “international Marxists” (in Kennan’s terms) who supported Trotsky’s idea of a “perpetual revolution” and those who supported Nikolai Bukharin and Joseph Stalin’s idea of “socialism in one country” (or in the case of the Soviet Union, a series of closely affiliated republics). Both Trotskyists and Stalinists tended to agree with an idea proposed by 19th-century Prussian Marxist revolutionary Joseph Arnold Weydemeyer: “the dictatorship of the proletariat.” However, Weydemeyer’s idea of direct democracies of workers’ councils to control the means of production never came to be for the Soviets. Instead, the Stalinist bureaucracy was creating a new ruling-class clique. While Kennan clearly did not communicate an understanding of Stalin’s support of “socialism in one country” and mistakenly portrayed the Trotskyist position as dominant, he diagnosed the problem as a “totalitarian dictatorship” under Stalin. There could be no cooperation. Instead, “containment” was the only way forward.

Kennan’s vision, shared by Truman and other Cold War hawks, ensured that all evidence from Greece to Indonesia and from Chile to Tehran would be read through the lens of containment. The Soviet Union expanded territorial control in Eastern Europe in 1939–1941 as a direct result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-aggression Pact. The pact has been often mischaracterized as an “alliance” but was instead simply a promise for the two powers to not invade one another directly, yet. Although Soviet influence in Poland was destroyed, the Lithuanian SSR was created and the Belorussian SSR and Ukrainian SSR expanded their territories. From the view of Washington, the territories initially lost during the direct invasion of Eastern Europe by Nazi Germany in World War II had not just been regained. Soviet influence had also expanded to the People’s Republics of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Albania, along with China. Most Americans did not understand the nuances of the Tito-Stalin Split and would similarly fail to understand those of the coming Sino-Soviet Split of 1956. In their uniformed understanding, the specter of Soviet totalitarianism simply threatened to take over the world. In the context of aiming to remove trade barriers and “prevent the spread of communism,” Washington launched the Marshall Plan, named for Secretary of State and General George Marshall in the spring of 1948. The idea was supported by a commonly held belief that a predecessor to the rise of fascism was economic ruin. Consequentially, to prevent a redescent into authoritarianism in Europe, the United States should rebuild Europe, especially Western Europe (i.e., France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and the BDR). In total, some $13 billion—around $114 billion in 2020—in aid was transferred to Europe, which was supported by the growth of the American economy.

The Marshall Plan relied on American access to capitalized raw materials, such as Chilean copper in Latin America that had been guaranteed during the previous era of American imperialism in Latin America. These raw materials were then sent to the United States to support the burgeoning manufacturing industry. The American reliance on the exploitation of Latin America for economic purposes helps to explain why Cold War hawks believed it was so crucial to “fight the spread of communism” in that region. Furthermore, the Marshall Plan was soon countered by an even greater Soviet spending plan, amounting to $15 billion invested in Eastern Europe. Stalin aimed to prevent others from following Tito and splitting from Moscow. Hence, Poland, Hungary, Albania, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia tended to follow the five-year plan model of industrialization, developing highly centralized economies. On the other hand, even in those economies built up by the Marshall Plan in Western Europe, privatization was countered by an expansion of social welfare programs in the post-war environment. For example, in the U.K., the Labour Party’s Attlee ministries from 1945 to 1950 and 1950 to 1951 concentrated on massive expansion of social welfare, built the National Healthcare System, expanded support for public housing, and led a dramatic expansion of workers’ rights. The only country left out of these developments was Franco’s Falangist regime in Spain. Deeply ultranationalist, authoritarian, and arguably a local brand of fascism, the Falangists had supported the German-Italian Axis in World War II, despite proclaimed neutrality. Thus, Spain was left out of the Marshall Plan. However, by 1951, Franco’s firebrand anti-communist stance made him a desirable ally of Washington. Raw materials from former Spanish colonies in Latin America, after all, were still being used to aid the industrialization of Western Europe.

In addition to economic policies, military alliances were another major strategy that American politicians claimed would help prevent the spread of communism. In April 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was signed by Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. In effect, NATO (1) prevented these states from having conflict with one another and (2) guaranteed mutual aid should one of the member states be attacked. Thus, NATO was argued as an effective way to bolster against the spread of Stalinist meddling in European politics, even as Stalin himself showed few real ambitions of doing so. NATO was quickly invoked in the name of the defense of the Korean peninsula during the Korean War (1950–1953), and through participation in the Korean War, the Turkish government would also guarantee a seat as a new signature to the NATO alliance in 1952. By 1955, the signatories of the Baghdad Pact formed a parallel Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), which included the United Kingdom, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan, with the United States joining the military committee of that alliance by 1958. Similarly, the members of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) signed the Manila Pact on September 8, 1954. In this case, membership included the Philippines, Thailand, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Pakistan, and France.

In the context of the formulation of NATO, CENTO, and SEATO on the one hand, along with the Warsaw Pact on the other, it would appear as though most of the world was somehow aligned. Yet, this was not the case. The First Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference, also known as the Bandung Conference, was held in Bandung, West Java, from April 18 to 24, 1955. At Bandung, an initial 29 participants representing mostly newly formulated countries—yet 1.5 billion people, or 54% of the population of the earth—gathered to produce an alternative vision of a global community. With leadership from Vietnam, Cambodia, Burma (Myanmar), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the People’s Republic of China, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Ghana, Libya, and even most of the CENTO member-states, Bandung presented a unique challenge to the vision of the world as understood by the Washington Consensus. Instead of seeing the world as divided between capitalism and communism, although some were ardent supporters of one system or another, most of the attendees to the Bandung Conference accepted mixed economies as the path to responsible development. Furthermore, they were united by their opposition to colonialism and neocolonialism in all its forms. Even more significant, these states were shaken by the violence of bombing campaigns, including and especially the American use of nuclear weapons.

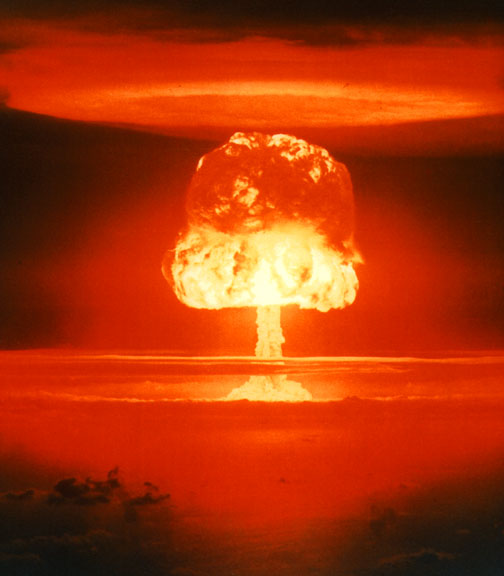

Alarmingly, the Soviet Union had detonated a nuclear weapon in a test explosion in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (now Kazakhstan) in August of 1949. From that point onward, a Soviet-American arms race resulted in the two powers stockpiling tens of thousands of warheads. By 1952, the United Kingdom would test a weapon in Australia. By 1960, France had detonated a weapon in French Algeria, with Israel following in the same year and the PRC just four years later. Ten years later, India would follow, with the ironically named “Smiling Buddha” weapon. Yet, most stockpiles were built in Soviet states and the United States, with both powers developing frighteningly advanced missile guidance systems, air forces, and submarines, capable of enough destruction to demolish the entire planet several times over, in part, based on the principle that this “mutually assured destruction” would prevent an all-out war. Still, with a high of over 70 thousand active weapons in 1986, and with in mind the destruction of mainland Southeast Asia from the air during the Second Indochina War (Vietnam War), coupled with the memory of the firebombing of Tokyo along with the nuclear explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is clear that opposition to forms of “the air war” raised at the Bandung Conference was prescient.

During the same year that the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was formed in Belgrade, the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament (ENCD) was sponsored by the United Nations. With representatives from the NATO bloc and the Warsaw Pact, along with leadership from NAM states, such as Burma (Myanmar), Ethiopia, and India, the ENCD succeeded in negotiating a global treaty on the Non-Proliferation of nuclear weapons (NPT) between 1965 and 1968. Yet, although they were allowed to participate in negotiations, the Soviet Union and the United States continued to stockpile weapons. Hence, NAM states such as India and Pakistan refused to sign on to the NPT. South Africa developed nuclear weapons under the apartheid regime in the 1970s. However, in 1991, during the final days of the regime, around the same time the De Klerk government finally agreed to free Nelson Mandela, the South African government scrapped their weapons and joined the non-proliferation movement. Also in 1991, Kazakhstan left the Soviet Union and inherited a massive nuclear arsenal, larger than those of Britain and France. Nonetheless, Kazakhstan also became the first country to scrap its Cold War–era arsenal, while Pakistan and North Korea joined the list of states with access to a weapon in 1998 and 2006, respectively. This is to say, despite the “end” of the Cold War, the legacy of American and Soviet stockpiling haunts the world to the present.

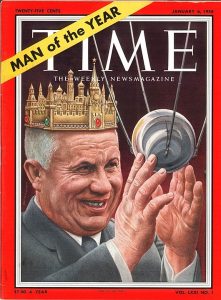

Still, after the NPT was initially formed in 1968, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved their doomsday clock backward, from “7 minutes to midnight” to “10 minutes to midnight.” In 1991, they had moved it back to “17 minutes to midnight.” Although the current clock sits at 100 seconds to midnight for 2020, as we read and write, it is important to remember that the historical evidence suggests that disarmament can be achieved, especially through combinations of bilateral and multilateral negotiations. During the era of the growth of the non-aligned and non-proliferation movements, changes in Soviet politics were brought about by the death of Stalin in 1953. The new Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, distanced himself from Stalin’s “cult of personality.” Khrushchev also allowed for criticisms of Stalinist policies during the Ukrainian famine, purges, and utilization of forced labor as punishment. Further, he announced a policy of “peaceful coexistence with the West.” Although he had formed the Warsaw Pact to counterbalance NATO, Khrushchev primarily aimed to ensure that communism provided a higher standard of living for workers. This proved to be a difficult task, given the enormous expenditures, arguably wasted, on the Soviet military budget. Lessening international tensions could, then, free up resources for social programs.

Still, there were limits to Khrushchev’s reforms. Political reforms allowing for greater participation of dissenting parties in Hungary created the possibility that other members of the Warsaw Pact might seek similar reforms, along with increasing acceptance of anti-Soviet protests in 1956 from Hungarian nationalists, students, and other reformers. The Soviet allies in the Warsaw Pact gathered their militaries together and sent them into Hungary to put down any potential dissent.

Questions for Discussion

- When you review the list of members of the “nuclear club,” are there any countries on it you weren’t expecting to see?

- Suppose you are a diplomat: How would you work to reduce a nuclear arsenal?

The Cold War in Asia

Most Americans have probably thought about the Cold War in the Asia and Pacific region as a narrative that begins with the contestation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the future of the Japanese Empire. Indeed, after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in 1945, the Japanese Empire was potentially in a position where bilateral negotiations and a direct surrender to the Soviet Union would have been most fruitful. Then, after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the position of the Japanese government changed dramatically, and direct negotiations were held with the United States. However, if we think about the Cold War as a period of a battle of ideas, the history begins earlier. Much of the Cold War in Asia involved open violent conflict between right-wing authoritarian republicanism on the one hand and left-wing revolutionary Marxist-Leninism on the other. Thus, the history of the conflicts of the Cold War in Asia can be traced to the Shanghai Massacre of 1927. In April 1927, an alliance between the Guomindang (GMD; alt., Kuomintang, KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) collapsed during Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Campaign. Hundreds of communists in Shanghai were arrested and massacred on direct orders from Chiang Kai-shek. By August of 1927, the communists, led by a young upstart named Mao Zedong, launched a formal uprising.

In 1928, the communists banded together, forming the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army. Known as the “Red Army” for short, they fought overtly against the Guomindang until the Japanese invasion of Manchuria began the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and World War II in the Pacific. Then the Red Army and the Guomindang halted fighting one another, briefly forming an alliance to become the National Revolutionary Army (NRA). However, open fighting between the two factions resumed in 1946. Yet, the Guomindang faction of the NRA had suffered many more casualties than the Red Army, primarily because they relied on conventional warfare strategies instead of guerrilla tactics. The battle-weary Guomindang collapsed and retreated to the island of Taiwan, which had previously been ruled by the Japanese Empire from 1895 through 1945. While Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland in 1949, Chiang Kai-shek proclaimed the Republic of China (ROC) on the island of Taiwan, also in 1949. Taiwan has always struggled for recognition, however, especially as Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists ruled the island with an iron fist, establishing martial law from 1949 through 1987. Currently, fewer countries recognize Taiwan than the nation of Palestine. However, the United States recognized only the Republic of China in 1949 and even recognized the republic’s preposterous claims to the entirety of the mainland. Yet, after negotiations with the PRC began during President Richard Nixon’s visit to the mainland in 1972, the United States government broke off relations with Taiwan in 1979 to maintain better relations with Beijing. Today, Taiwan only has formal relations with 13 out of 193 United Nations member states, none of which are major world powers or permanent members of the Security Council.

In Japan, the United States rebuilt the country to an even greater extent than much of Western Europe. The motivation was twofold: (1) a realpolitik juxtaposition of American control in the Asia-Pacific region against Soviet control in the mainland of northern Asia and (2) a sense of a need for restitution for the war crimes Americans committed by firebombing major Japanese cities—such as Kyoto and Tokyo—and dropping atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1947, a new constitution established Japan as a formally “pacifist” country. However, the U.S. military continued its formal occupation (1945–1952), and the Ryukyu Islands were ceded to the United States. Although the northern part of the archipelago was returned to Japan in 1953, the remaining islands, including Okinawa, remained under U.S. control until 1972. Nonetheless, in accordance with the U.S.-Japanese Alliance (1951), the American military has been allowed to maintain bases on Okinawa ever since. Thus, Okinawa bristles with American bases, with at least 10 distinct bases on the small island, representing the branches of the army, air force, Marine Corps, and navy. These bases are closer to Taiwan, the mainland of China, and the Korean peninsula than they are to Tokyo. Hence, they played a significant role in the Korean War and the Second Indochina War (Vietnam) while also acting as implied support for the Republic of China on Taiwan for five decades after 1949. Finally, Japanese corporations would also support development efforts in Southeast Asia from the 1950s onward, especially as the Japanese economy grew to dominate automobile, electronic, and other high-tech manufacturing sectors of the global economy by the 1980s.

The Korean peninsula had been contested between empires for much of the 20th century. Japanese rule began in 1910. A provisional government opposed to Japanese rule was formed in exile in China but held power only nominally among certain Korean patriots between 1919 and 1948. In 1945, Allied officials held such pejorative views of their Korean partners that they debated when Koreans would be ready for “self-rule.” Americans proposed to divide the peninsula at the 38th parallel in a joint agreement with the Soviets. All parties assumed the partition would be provisional before a trusteeship would then be established, and there would be a five-year transition to self-rule by 1950. However, Korean nationalists opposed the agreement. Further, other factors ensured Soviet-American negotiations failed by 1947. The “Korean Question” was referred to the United Nations, just as the “Israel-Palestine Question” had been. However, unlike the 1947 Partition of Israel-Palestine, the Soviet Union would not agree to the 1948 partition of Korea. A veteran of the Chinese Red Army and Korean anti-fascist resistance, Kim Il Sung, consolidated power north of the 38th parallel.

South of the 38th parallel, Americans backed the 1948 election of Syngman Rhee. As a parliamentary democracy, Korean elections occurred in cycles. Even though Syngman Rhee’s National Association won only 26% of the vote in the May cycle—with most of the remaining vote going to independents (40%)—in the July elections, Rhee secured a shocking and suspicious 92.3% of the vote.

In response to Rhee’s inauguration, Kim Il Sung proclaimed the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea at Pyongyang in the northern part of the peninsula, while the people of Jeju Island in the Eastern Sea protested Rhee’s regime. Syngman Rhee brutally suppressed dissent. He used the military to put down protests, and massacred more than 80% of more 14 thousand people of the Jeju Island during the Jeju Uprising, enrolled suspected communist sympathizers in a supposed “re-education” program called the Bodo League, and imprisoned tens of thousands of others. When Rhee ordered the massacre of the Bodo League in the summer of 1950, some 100–200 thousand people were massacred, many of whom were civilians with zero connection to communism or communists.

In the context of the violent repression of Rhee’s regime south of the 38th parallel, Kim Il Sung ordered an invasion of the south in June 1950, aiming to unite the peninsula. The United Nations Security Council ordered a military response, led by the United States, with the additional support of NATO allies. Surprisingly, instead of using its veto power as a permanent member of the security council to veto the resolution, the Soviet Union abstained. Perhaps this was because Kim Il Sung’s army had so quickly taken the south that the Soviet leadership viewed the Korean peninsula as a non-issue, while also causing NATO representatives to believe that Stalin might have green-lighted the invasion. By October, U.N. forces had pushed northward, retaking the entire south, and moving into Pyongyang, moving all the way to the Yalu River, along the border with the People’s Republic of China. In response, Mao Zedong ordered millions of soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA, f. 1948) across the border in a preemptive strike against possible incursion into Chinese sovereign territory and to defend his comrades in Pyongyang.

The hotheaded American general Douglas MacArthur aimed to escalate the war at this stage and contemplated the use of nuclear weapons. As the Soviets also were armed with nuclear weapons after 1949 and Stalin held a non-aggression agreement signed with the People’s Republic of China, President Harry Truman fired MacArthur, aiming to de-escalate the situation. Nonetheless, the Republic of Korea (ROK) remained ruled by a rotating series of military strongmen, with rare exceptions, and democracy would not emerge until after the establishment of the Sixth Republic in 1988, beginning a period of transition, and Kim Young-sam became the first civilian president in 30 years in 1992. By the 1990s, the Republic of Korea had transitioned its economy following the Japanese model of development, especially for high-tech manufacturing, although nearly 30 thousand American troops remain stationed in the country as a remnant of the Cold War. Repeated Korean attempts at bilateral peace processes have furthermore been thwarted by American insistence on direct negotiations with Pyongyang.

The persistent American military threat in the Korean peninsula proved key to Kim Il Sung’s ability to consolidate power in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the northern section of the peninsula. After between 300 and 600 thousand North Koreans, between 200 and 400 thousand Chinese, and some 300 Soviet operatives had lost their lives in the fighting—along with between 100 and 200 thousand South Koreans, more than 35 thousand Americans, and more than 4 thousand U.N. and NATO allies—Kim Il Sung transformed the Worker’s Party of North Korea (1946–1949) into the contemporary Worker’s Party of Korea (WPK) by 1949. By unifying the Tonghak-inspired Chondoist Chongu Party (f. 1946), the Korean Social Democratic Party (f. 1945), and the WPK into a single political apparatus under the “Democratic Front for the Reunification of Korea” in 1946, Kim Il Sung demonstrated his political acumen for political consolidation, utilizing juche ideology as an ultranationalist deviation from Marxist-Leninism. The devastation of the Korean War in the DPRK was enormous.

Almost every major building had been destroyed by American-allied bombs, while civilian and military losses were proportional to Soviet loses in World War II. Although the conflict shifted to a stalemate in 1953, officially it remains unresolved. A post-war famine wracked the northern part of the peninsula as local officials overestimated the size of the harvest by 50–70%, and approximately 800 thousand died. Political purges, imprisonment of dissenters, and torture became common tools for maintaining political control. DPRK leaders frequently plotted assassination attempts on ROK politicians from the 1960s through the 1980s. Nonetheless, there were radical improvements in the status of women, availability of housing, health care, increases in life expectancy, and decreases in infant mortality—which were even acknowledged by the American CIA—all of which remained in place until the North Korean Famine of 1994 to 1998. Furthermore, although Kim Il Sung’s close ties with the Chinese Communist Party were damaged substantially by “self-reliance” elements of juche ideology in the post-war climate, he managed to secure a legacy that guaranteed that his son, Kim Jong-il (r. 1997–2011), and grandson Kim Jon-un (r. 2012–present) would follow him as leaders of the DPRK.

Although Kim Il Sung’s career originated within the Red Army during the Chinese Civil War, by the 1960s, Kim Il Sung had mostly parted ways with both the Soviets and Mao Zedong, heading off on his own, as Tito had done in 1948. Furthermore, Mao Zedong would also develop foreign policy in a distinct direction, while the senior Chinese diplomat Zhou En Lai would appear at Bandung in 1955 and secure Chinese observer status in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) by 1961 in the context of the Sino-Soviet Split. Shortly after the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had invaded and annexed Tibet, forcing a young Tenzin Gyatso—known internationally by his title of the “Dalai Llama” and as the senior leader of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism—into exile after the subsequent 1959 Tibetan uprising. The western autonomous Turkic region of Xinjiang had already been incorporated in 1949, and thus, by the middle of the 1950s, the territory of the People’s Republic of China had been greatly expanded, bordering directly on the Soviet Union. Upon Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalinism and the “cult of personality,” the Maoist and Soviet interpretations of Marxist-Leninism began to sharply diverge. By 1961, Beijing formally denounced Soviet communism as “revisionist traitors.” During the same period, Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Deng Xiaoping presided over an “anti-rightist campaign” from 1957 to 1959 in an attempt to purge critics from the party, while Mao Zedong, as chairman of the Central Military Commission, the Communist Party, and the People’s Republic, backed “The Great Leap Forward” (1958–1960).

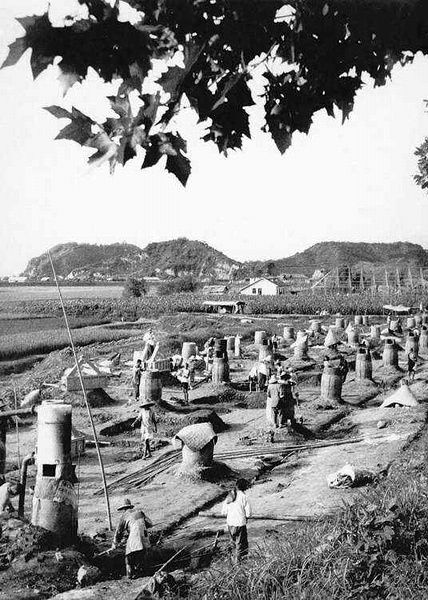

The Great Leap Forward was an attempt to force an industrialization of the Chinese economy along a Leninist model, as interpreted by Mao Zedong and other party officials. “Backyard furnaces” were constructed across the people’s republic, and as agricultural workers shifted to industrial production, agricultural output plummeted. Some 25 thousand “people’s communes”—comprised of 5 thousand families each—distributed food equally and freely among the workers but were forced to ration food at the onset of the Great Chinese Famine (1959–1961). Although the famine began because of environmental causes, it was worsened by Maoist policies. Fearing the purges of the anti-rightest campaign, low-level administrators over-reported their grain harvests. Because they were not working with accurate information, mid-level administrators insisted the famine could not be that bad and food shortages could be resolved by working the agricultural workers harder and rationing food. Hence, senior-level party officials also had inaccurate information, all the way to Mao Zedong, who insisted on maintaining exports, mostly to Eastern Europe, to secure capital to back the industrialization of the Great Leap Forward. The most reliable estimates of the dead from the famine coupled with state violence from this period range between 15 and 45 million.

The failures of the Great Leap Forward and the Anti-Rightist Campaign caused a split within the Chinese Communist Party. After Liu Shaoqi succeeded Mao Zedong as the chairman of the republic in 1959 and the devastation of the famine became clear, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping both publicly criticized Maoist policies. Liu Shaoqi went so far as to proclaim that the famine was the result of 30% natural causes and 70% human error. Yet, Mao Zedong retained a powerful position as chairman of the Communist Party and the Central Military Commission. The PLA attacked non-aligned India over a brief border dispute in 1962, under Mao Zedong’s guidance, and the chairman launched a Socialist Education Movement in 1963 that became the precursor to the Cultural Revolution (1966–1968). The relationship between Mao Zedong and Liu Shaoqi had fully deteriorated by 1966, as Mao Zedong often publicly subtweeted Li Shaoqi with vague references to the “bourgeois headquarters” of the Communist Party.

The Cultural Revolution would then rely upon a revolutionary Red Guard, led by students, to target the Four Olds: ideas, culture, habits, and customs. Remains of Buddhist monks, temples, and other symbols of China’s imperial past were targeted for destruction. Students denounced professors and mentors and had them arrested, and those denounced were forced to endure public criticism sessions. Somewhere between several hundred thousand and 2 million civilians, Red Guard, and military personnel were killed in the civil disorder. Another border dispute with India erupted in 1962, and then, in 1969, a direct Sino-Soviet border war ensured the long-term disintegration of Sino-Soviet relations. These ongoing border disputes—including the much later Sino-Vietnamese conflict of the Third Indochina War in 1979 and the 1987 Sino-Indian skirmish, along with the invasion of Tibet—contributed to the long-standing American perception that there was a “Bamboo Wall” at the Sino-Southeast Asian borderlands, representing one reason why the United States became so deeply entrenched in attempts to supposedly “defend” Southeast Asian states during the Cold War.

Questions for Discussion

- How was Kim Il Sung able to secure so much power in the DPRK?

- How does this compare to the PRC?

- Was Mao Zedong an effective leader of China?

Between 1945 and 1957, every country in Southeast Asia gained independence. At the same time, the Cold War in the region was marked by intensive, violent, civil conflicts that were, by and large, poorly understood by Soviet and American diplomats. The much more skilled, and better informed, Chou En Lai worked tirelessly to build from the Bandung Conference in 1955, securing good relations with founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement, including Cambodia, Myanmar, and Indonesia as well as Laos, which secured non-aligned status in 1964, and Malaysia, which joined the Non-Aligned Movement in 1970. In the Philippines, the anti-Japanese insurgents, known as the “Hukbalahap,” continued their people’s revolution after 1945, throughout the presidency of Manuel Roxas. By 1950, the American CIA was deeply invested in putting down the so-called Huk rebellion, leading to their backing of then Secretary of National Defense Ramon Magsaysay. Campaigning at the head of the oldest right-wing nationalist party in the region to the song “Mambo, Mambo, Magsaysay”—without whom, the song feared, “our democracy will die”—Magsaysay secured a victory with nearly 69% of the vote in the 1953 election and brutally crushed the Hukbalahap resistance, with the aid of CIA-informed psychological warfare, by 1954.

From the middle of the 1950s through the 1970s, Americans and their allies would attempt to utilize similar “counter-insurgency” strategies, with varying degrees of success—failing in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos but succeeding in what became Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. As Burma (Myanmar) had been part of British India, it was not subject to the same strategies as anti-fascist Thakin U Nu moved from his simultaneously anti-British and anti-Japanese stances to secure a truly non-aligned status. However, Burmese politics were unstable, and he requested General Ne Win to act as head of a “caretaker government” in 1958, although in the 1960 elections, U Nu’s faction, known as the “Union Party,” won by a landslide, only to be overthrown by General Ne Win in a 1962 coup d’état, resulting in a military government that would control Burma solidly until it was challenged by the 8888 Uprising, a pro-democracy movement inspired by U Nu and others, where the daughter of Aung San emerged as an important national icon: Aung San Suu Khi.

Southeast Asia’s experience with socialism was more complex than American politicians and military officials gathered. On the one hand, revolutionary nationalists such as Hồ Chí Minh would make use of Marxist-Leninist communism to support their independence movements. This was especially the case in the Indochinese Communist Party, which sought to inspire anti-French revolutions in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. On the other hand, in the Theravada Buddhist countries of Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia, various forms of “Buddhist Socialism” developed. In Myanmar, this philosophical position of a mixed Buddhist and socialist society was held by U Nu. In Cambodia, it was the position put forward by Prince Norodom Sihanouk in the 1950s. In Thailand, a young student named Jit Phumisak had been hired to translate The Communist Manifesto into Thai by American operatives in 1953, under the premise that this would scare Thais away from communism. Instead, he became inspired and wrote The Face of Thai Feudalism (1957) before he was branded as a communist and arrested. After he was set free in 1963, he continued to speak of a Thai form of socialism and would join the Communist Party of Thailand in 1965. One year later, he was dead—shot, presumably, at the behest of authoritarian anti-communist Field Marshal (and then prime minister of Thailand) Thanom Kittkachorn.

Thanom Kittkachorn had succeeded the Thai fascist general Plaek Phibungsongkhram (known widely as “Phibun”). Phibun had forced himself into the seat of prime minister from 1938 to 1944 and seized it again from 1948 to 1957, rebranding his fascism as anti-communism during his second term. Thanom Kittkachorn ruled briefly in 1958, although the death of his successor in 1963 returned Thanom Kittkachorn to the post from 1963 through 1973. Amid a pro-democracy student movement, he attempted to stage a self-coup, but the October 1973 popular uprising forced King Bhumibol Adulyadej to consider democratization. When Thanom Kittkachorn returned from exile in 1976, he was met with more protests. Branding the universities as hotbeds of radicalism, the Thai military and right-wing vigilantes surrounded the campus of Thammasat University and attacked unarmed students holding a pro-democracy rally on the campus grounds. Thousands were arrested. Although only 19 were imprisoned long-term, they included former University of Wisconsin history professor Dr. Thongchai Winichakul, a world-renowned historian who has done much to preserve the memory of that day. Eyewitness accounts recorded that the military and right-wing vigilantes used rape, torture, and desecration of victims’ bodies as strategies of intimidation. Military rule had been re-imposed by a bloody coup in 1976, although by the 1980s, King Bhumibol and Prem Tinsulanonda aimed to end the persistent pattern of military interventions in Thai politics. However, in 1991, another coup, led this time by Suchinda Kraprayoon, led to the deaths of more than 100 medical volunteers, more than 50 protesters, and 175 disappearances, as the military brutally crushed anti-coup protesters in “Bloody May” on May 17–20, 1992. Nonetheless, throughout the entire Cold War, American advisors and government representatives would back these dictatorial regimes in the name of anti-communism.

American investment in Southeast Asia was tied not only to the Philippines during the Cold War but also to Vietnam and Indonesia. Indeed, there was American backing of French authorities during the World War II era under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, although he was reluctant to back French investment in Indochina. As mentioned in the previous chapter, a French reconquest of Indochina, including Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, was virtually completed before the Vietnamese general Võ Nguyên Giáp thwarted French forces at Điện Biển Phủ in the uplands of northern Vietnam in 1954. At the Geneva Accords in the same year, France and the revolutionary Vietnamese forces under Hồ Chí Minh agreed to divide the country at the 17th parallel, with the area south of the parallel expected to remain a French dependency, with elections to then be held to re-unify the country. However, the American president Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the “Domino Theory,” contending that if “you knock over the first one…what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly” in reference to his idea that the PRC (China), the DPRK (Korea), and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) were the first of the dominoes, with the implication that Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), and India could be the next.

A note on terminology

When it was clear that Hồ Chí Minh could benefit from the plan of the 1954 Geneva Conference, possibly with Võ Nguyên Giáp quickly leading forces to conquer the lands south of the 17th parallel, or possibly simply by winning the proposed elections, Gen. Ngô Đình Diệm rejected the solution. After all, Ngô Đình Diệm had now secured American backing for his staunch anti-communism, a far more promising prospect, from his view, than his previous French backing. Ngô Đình Diệm proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam, and American military advisers poured into the country, replacing French military advisors and foreshadowing an outright invasion of mainland Southeast Asia by American forces after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964. U.S. forces only peaked when the Johnson administration set the maximum number of troops in Vietnam at 549,500 four years later. The troop peak had been, in part, a direct result of a second psychological victory of Võ Nguyên Giáp during the Tet Offensive. In the Tet Offensive, Võ Nguyên Giáp had led the formal People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) to coordinate attacks with the guerrilla army of the National Liberation Front (NLF), hitting more than 100 cities and military posts throughout the Republic of Vietnam. In essence, the Tet Offensive proved that PAVN and the NLF could choose the time and place of battle, no matter how many troops Americans would send into the country or how many bombs would be dropped.

The bombing of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos was so severe during the Second Indochina War that the countryside and social, political, and economic infrastructure of these three countries were totally devastated. Indeed, the United States and its allies dropped 7.5 million tons of bombs on former Indochina. With the nuclear bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima exempted from the count, it was pound for pound, double the amount of bombs dropped on all of Asia and Europe during World War II. Unexploded ordnance would claim lives for decades to come in Southeast Asia. The bombing and U.S.-backed coup in Cambodia in 1970 eliminated the non-aligned Norodom Sihanouk from power, established another military dictatorship as a “republic,” and created the political instability that deepened the conflict of the Cambodian Civil War. Indeed, Yale historian Ben Kiernan has convincingly argued the U.S. bombing paved the way for the Khmer Rouge (from the French for “Red Khmers”; i.e., “Communist Ethnic Cambodians”) to rise to power. Yet, PAVN and the NLF could not be beaten in Vietnam. After 58,000 Americans, thousands of their allies, more than a million PAVN and NLF fighters, and more than 2 million civilians had died, the Americans were defeated. Ironically proclaiming “victory” at the behest of Nixon, the Americans retreated in 1973. Millions of dollars were dumped into the failed state of the Republic of Vietnam, which crumpled during a memorial “Hồ Chí Minh campaign,” again led by Võ Nguyên Giáp, in April 1975. Hồ Chí Minh himself had died of heart failure at his home in Hanoi in September of 1969 at the ripe old age of 79 years old. Though his dream of a unified and liberated Vietnam would be realized in 1976, with the Democratic Republic and Republic united after a peace agreement, a new constitution, and the formulation of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), a government that survived the Cold War and remains in place to this day, with the slight irony that the de facto single-party state is one of the few governments in the region to have a regular peaceful transition of power between elected heads of state. Yet, Hồ Chí Minh’s original dream of a unified series of “Indochinese Republics,” as it were, inclusive of Laos and Cambodia, would never be realized.

For more information

Learn more by explore the resource Bombing missions of the Vietnam War: A visual record of the largest aerial bombardment in history by Cooper Thomas

In the case of Cambodia and Laos, although movements that initially viewed themselves as Communist or Marxist-Leninist would take power in each case in April 1975, their fates would diverge. There would be similarities in each case in that families who feared persecution by communists fled, as was especially the case with families who were closely associated with the previous monarchies or military governments. The situation was desperate. 250,000 refugees from Vietnam had perished at sea by 1986. In total, some 2.5 million refugees from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were resettled, first at refugee camps in Thailand and Malaysia. Then, refugees moved to the Philippines and Indonesia, and outward to Canada, France, Australia, and the United States. Yet, whereas the revolutionary Pathet Lao remained more closely intertwined with and supported by their Vietnamese comrades, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia turned toward a stauncher form of ethno-nationalism by comparison, developing a unique ideology under Saloth Sar, most often known as “Brother Number 1” or “Pol Pot.” Pol Pot’s establishment of the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime quickly invoked certain far-left wing revolutionary ideologies of Maoism, taking them to even further extremes. Perhaps most notably, he attempted to abolish markets by devaluing existing currency to zero and printing a new currency and turning the urban population out to the countryside. The radical transformation built numerous dykes and canals, many of which are still standing today. Yet, when as wartime famine also hit the country and the DK regime began to purge party members in the name of establishing control over a perceived social revolution, the crisis deepened.

Far-right-wing ethno-nationalist sentiment had grown in popularity in Cambodia during the civil war of the 1950s and 1960s. As the violence worsened after 1975, those ethnic groups that were not considered part of ethnic-Khmer national identity by the DK regime were targeted: Vietnamese, Chinese, and Cham among them. In the case of the Cham population, the additional “otherness” of their religion (Islam), along with their occupations as moneylenders and textiles traders, established them as “outside” of the proposed new national identity. Ethnic Khmer Buddhist monks were also targeted in the genocide, albeit not to the extent that Cham clerics were. Yet, it is important to remember that allies of the former American-backed Republic of Cambodia (1970–1975), including, especially, doctors, teachers, lawyers, and politicians, were targeted regardless of their ethnicity. Often that violence invoked the rhetoric of class revolution. Such was also often the case with the ethno-nationalist violence targeting ethnic minorities.

According to the Documentation Center of Cambodia, approximately 1.3 million people were executed during the genocide and buried in mass graves, with this form of execution accounting for approximately 60% of a total of around 2 million deaths, or approximately 20%–25% of the total population in the country. In 1978, Vietnamese troops, led yet again by the communist general Võ Nguyên Giáp, invaded Cambodia, beginning the Third Indochina War. By 1979, Võ Nguyên Giáp’s PAVN troops had taken the rest of the country, forcing Pol Pot’s DK regime to retreat to the outer reaches of the province of Battambang, along the border with Thailand. Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia prompted a reprisal from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which attempted an invasion of Vietnam, but the forces of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) were quickly beaten back and forced to retreat. In Cambodia, dissenting former DK regime politicians were installed in collaboration with the Vietnamese military, which established the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) and occupied the country until 1989. The Americans, by contrast, backed the DK regime during the entirety of the remainder of the Cold War, recognizing Pol Pot’s genocidal regime as the “legitimate government” of Cambodia until the 1990s, at which point the United Nations initiated a peace process, beginning with a formal ceasefire in 1991.

Although the American recognition of the DK regime throughout the Carter and Reagan administrations made clear that American Cold War policy was no longer about anti-communism in Southeast Asia, it is important to recognize that in the case of Indonesia, anti-communism was, much like the cases of Thailand and the Philippines, the justification for the backing of an authoritarian regime. At the time of the invocation of the “Domino Theory” during the Eisenhower administration, in 1954, the Indonesian government was led by revolutionary nationalist Sukarno and his Nationalist Party of Indonesia (PNI). After the 1955 Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference was held at Bandung, Sukarno’s PNI would officially become an international leader in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). In 1958, right-wing generals attempted a coup and began an authoritarian crackdown on the small Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) on the islands of Sumatra and Sulawesi, which the military had seized control of as part of the attempted coup. To regain control, Sukarno proposed a unity of his centrist-nationalism, the religious right, and left-wing communism under a new platform of “Guided Democracy.”

Although the PKI would never receive enough official recognition under this platform to establish formal political control, in part because of their overt criticism of Sukarno’s handling of the budget, it did allow enough peace for social organization affiliated with the PKI to grow. Unions organized under a Central All-Indonesian Workers Organization, youth organized the People’s Youth, and women organized the Indonesian Women’s Movement (known commonly as “Gerwani” for short). Gerwani was headed by such activists as Sri Koesnapsijah, who was well known for her punchy prose opinion pieces. They advocated for gender equality and equal labor rights for women, which was a distinct challenge to the patriarchal order of the religious right in Indonesia, made up of Christian priests and Muslim clerics. Gerwani was also a challenge to the all-male leadership of the right-wing and far-right-wing generals in the Indonesian military. However, the mid-1960s political situation in Indonesia was still unstable.

A shadowy attempted coup known as the “September 30th”—or alternatively, the “October 1st”—movement resulted in a violent reprisal led by the far-right members of the Indonesian military leadership, led by General Suharto in 1965. The official story of the military was that the “September 30th Movement” was a PKI affair, and hence, they needed to crack down on the PKI to retain control of the country. However, a well-accepted Cornell paper by Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey, published only in 1971, suggested the evidence was that the coup and countercoup represented an internal military struggle for power and that General Suharto clearly recognized an opportunity to seize control of the country. In any case, General Suharto led a brutal purge of the PKI from the country. Those with accused links to the PKI—including union, youth, and women’s movement leaders—were arrested, tortured, and executed. Traditionalist Muslims (abangan) and atheists were targeted. On Lombok, Balinese were targeted; on Sumatra, Javanese. Throughout the archipelago, but especially on Borneo and Sumatra, Chinese were the main targets of ethnic violence.

By 1967, General Suharto forced President Sukarno to step down. In the end, at least 500,000—and more likely, up to 1.2 million—civilians were murdered by far-right violence, including massacres and executions committed by the Indonesian military but also including massacres and executions committed by right-wing and far-right vigilante gangs. Recently released U.S. Embassy cables from 1965 to 1968 prove that the Americans were intimately aware of the violence and nonetheless supported General Suharto for the sake of anti-communism and American business interests. The first genocide in Indonesia was an immediate precedent for the Indonesian invasion, occupation, and mass terror campaign that committed a second genocide in East Timor in the late 1970s, again with American backing, as the U.S. military had been supplying weapons, training, and advising to the Indonesian military since the 1950s under the principles of the “Domino Theory.” Indeed, the tyranny of the far-right regime of General Suharto would receive American backing until he was forced to resign by a popular pro-democracy movement that brought the regime to an end in the wake of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, which we will cover in the next chapter.

Questions for Discussion

- How would you describe the Cold War in Southeast Asia? Was it really about anti-communism? Why or why not?

Cold War in North Africa and Western Asia (Middle East)

In the last chapter, we examined how the partition of Israel and Palestine in 1947 immediately led to a series of conflicts between Israel and nearby neighbors in Southwestern Asia by 1948. With the Israeli defeat of the Arab League forces in 1949 at the end of the 1947–1949 Palestinian War and the continuation of post-colonial trends, there was an upsurge of pan-Arab sentiment and Muslim nationalism in Southwestern Asia and Northern Africa. The monarchy in Egypt had been pro-British and was seen as a colonial-era holdover. The Muslim Brotherhood, which had been hawkish in its support of Palestinian forces against Israel, turned its attention against the monarchy. In 1950, King Farouk of Egypt and Sudan had a personal fortune estimated at 140 million USD—the equivalent of about 3.6 billion USD in 2021—making him one of the world’s richest men at the time. His crackdowns on dissent were also incredibly unpopular. Consequentially, the “Free Officers” movement, led by General Muhammed Naguib and Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, decided to seize power. After the 1952 revolution, General Naguib became the first head of state of the new Egyptian republic and Sudan gained independence. Far-reaching reforms were put in place the next year; yet, when the Muslim Brotherhood tried to end Colonel Nasser’s life in 1954, he placed then president Naguib under house arrest and assumed the office of temporary head of state, forcing the British military to withdraw from Egypt. He was then formally elected in a 1956 referendum with a shocking 99.9% of the vote in favor of him as president and 99.8% of the vote in favor of a new constitution.

![By Not credited - [1] at Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27803863 Nasser held on the shoulders of a large crowd in the street](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/18/2022/05/Nasser_and_RCC_members_welcomed_by_Alexandria_1954.jpg)

Although the results of the election were indeed dubious, there is no question that President Nasser was incredibly popular with the majority of Egyptians in the 1950s, especially after he seized control of the Suez Canal, nationalized the Suez Canal Company, and in effect, kicked both the British and French colonialists out of the region. However, the Israeli military, during the ensuing Suez Canal Crisis, would take control of the Sinai Peninsula with the backing of the British and French militaries, although American advisors supported a peace process in 1956, particularly as they held an ambiguous position on Nasser’s rise to power. President Nasser himself was enormously popular, even as he established a secular state, separating religion and politics. Furthermore, he supported government intervention in the economy, especially on the principles of social democracy and to prevent foreign (i.e., British, American, or French) control. His support of social democratic economics led to the building of a social safety net across Egypt, improvements in education, improvements in healthcare, and greater potential for support for women’s rights. Furthermore, pre-independence Anglo-Egyptian Sudan had been represented at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia in 1955 by then chief minister Ismail al-Azhari. A native of Khartoum state in Sudan, after the revolution, Ismail al-Azhari became a prominent Sudanese politician, serving as the second prime minister (1954–1956) and third president (1965–1969) of that country. In Egypt, Nasser also formally supported the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), becoming a founding member of NAM in Belgrade in 1961. In addition to his staunch non-aligned stance, Nasser’s primary political positions expressed in “Nasserism” became the support of militant anti-imperialism, revolutionary republicanism, and Arab socialism.

President Nasser’s ideas of pan-Arabism and Arab socialism as well as non-alignment and anti-imperialism were influential on the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party of Syria and Iraq. Syria and Egypt even federated as the United Arab Republic from 1958 to 1961, which was part of the United Arab States, a loose confederation that also included the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. Yet, the Kingdom of Yemen was dissolved in 1961, and the Syrian coup of 1961 caused that country to leave the federation as well. A brief “Hashemite Arab Federation” of the monarchies of Syria and Iraq had also been formed in response to the founding of the United Arab Republic in 1958 but collapsed when King Faisal II of Iraq was deposed in July of that year, which led to the foundation of the first Iraqi Republic. A similar Nasserite-inspired revolution took power in Libya in 1969, and for a moment in the 1970s, the leader of the Libyan revolution, Muammar Gaddafi, even attempted to form a “Federation of Arab Republics,” which was proposed to include, at different times, Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Syria, and Iraq. The government of Egypt, then under President Anwar Sadat (1970–1981) even attempted to form a “union” within the federation with Libya (in 1973) and Syria (in 1976) but failed both times. Similarly, Muammar Gaddafi proposed to form an “Arab Islamic Republic” of Libya and Tunisia in 1972, but also failed.

Despite the failures of Arab socialism to create unions of federated republics, only loosely inspired by a Soviet model of governance, the political prominence of the Arab League (f. 1945) grew throughout the Cold War. By the 1950s, Sudan, Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco had joined the Arab League. The French war against Algerian independence had killed around 700,000 to 1 million people, uprooting more than 2 million refugees, but resulted in the formulation of an independent Algeria by 1962, which also joined the Arab League. By 1964, in a meeting in Cairo, the league announced support for the formulation of an organization to represent the peoples of Palestine. Palestine was then already a separate state from Israel, per the 1947 partition, although recognition of both states was disputed. In 1964, with the support of Arab League leadership, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) was founded in the Palestinian section of Jerusalem. Led by the center-left to left-wing Fatah Party (f. 1959) of Yasar Arafat, the PLO would advocate for armed struggle in the name of the liberation of Palestine as the only possible solution to the Israeli-Palestinian crisis until the 1990s, at which point Yasar Arafat signed the Oslo Accords with then Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1993.

While support of the Palestinian Liberation Organization was motivated in no small part by anti-Israel sentiment within the Arab League, internationally during the Cold War, many non-aligned anti-imperialists also supported the PLO. On the other hand, American military support of Israel was doubled and tripled during the Cold War based on the argument that this would stave off Soviet influence in the region. While European and American Jews—especially those Ashkenazim whose family members had been victims in the Holocaust—broadly supported the creation of the State of Israel and an overtly left-wing “kibbutzim” movement throughout the 1960s, that support would waver long term, as criticism mounted against the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinian civilians. Furthermore, while David Ben-Gurion’s Labor Zionist and Democratic Socialist “Mapai” Parties had initially made waves by becoming the first Israeli parties to truly de-segregate and allow Palestinians to join, they declined in power by 1968, which forced them to merge with the Israeli Labor Party. Although now simply a party that supported social democracy, the Labor Party controlled the Israeli Knesset until 1977, at which point the Likud Party (f. 1973) won in a landslide election. Likud as a right-wing Zionist-nationalist and conservative party then controlled Israeli politics for the remainder of the Cold War. As American advisors poured military arms, funds, and training into Israel on the premise of preventing Soviet influence from growing in the “Middle East,” Soviet advisors took a similar position in Syria during the Cold War. The Baathist Party in Syria retained power despite splitting with the Iraqi Baathists in the 1960s. From 1970 to 2000, the Syrian Baathists were led by revolutionary general and later president Hafez al-Assad. A 1971 Soviet agreement with President al-Assad would lead to the establishment of a naval base at Tartus, which remains under Russian control at this writing. Thus, Russian influence in Syria was retained even after the Cold War and throughout the Syrian Civil War of the 21st century.

A note on terminology

As mentioned elsewhere, we strive for accurate geographical terms in this text. The term “Middle East” appears above for the sake of the flow of the text. However, the proper term for the region that most Americans think of as the “Middle East” is Southwestern Asia. The term “Middle East” is not an accurate description of the region in question for a number of reasons. To begin with, it assumes that one is standing in Europe and that there is a “Far East” (Japan, China, Korea) as well as a “Near East” (Turkey, or the Ottoman Empire). Thus, the term “Middle East” originated in Europe to refer to lands between the “Near East” and “Far East,” including areas that are now Iraq and the Levant but also sometimes Afghanistan and Persia. Then, in the early 20th century, British imperialists began to use the term “Middle East” and “Near East” interchangeably, reflecting their desire to conquer Ottoman lands, including in Egypt. After the defeat of the Ottomans during World War I and the collapse of Ottoman power under the pressure of nationalist Turkish revolutionaries, the term “Middle East” began to almost exclusively refer to the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt. However, after World War II, American and British joint imperialist interests in capturing Iranian (formerly Persian) oil were a direct cause of the inclusion of Iran in the region, despite the geographical division of the Zagros Mountain range and the fact that Iranian and Persian cultures are much more connected to other Central Asian languages and cultures for the vast majority of human history. Furthermore, during the War on Terror, Americans introduced the term “Greater Middle East” to include everything from African countries—like Morocco, Libya, Algeria, Somalia, and North Sudan—to South and Central Asian countries (like Pakistan and Afghanistan as well as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan). The term was biased and deeply problematic because it simply was used as a formal political stand-in for anti-Muslim bias. It also does not make much sense for students studying in the State of Louisiana to use geographical terms that assume they are standing in Europe. Thus, we strive to use geographic terms that are more accurate and neutral in this text, including North Africa, West or Southwestern Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia.

Like French and British investment in the Suez Canal, American interests in the Western Asia, North Africa, and Central Asia (i.e., Iran) were not just motivated by anti-Soviet sentiment. BP—the British oil company that we now know as associated with its green-and-yellow starburst logo, with green lowercase “bp” initials often above the logo—began as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in 1908. The company changed its name to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1935 upon the request of the first shah of Iran, Reza Shah Pahlavi, who would be forced to abdicate in 1941, when a joint Anglo-Soviet invasion of the neutral state of Iran deposed him and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, replaced him. Although 1941 would also initiate a pathway toward the establishment of an elected government, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was concerned in the post-war climate about the growing Tudeh Party, a left-wing Iranian party that represented both communists and socialists. The Shah appointed Mohammad Mossadegh to the position of prime minister after the parliament had voted for him overwhelmingly (79–12) to assume the role in 1951.

A moderate socialist in his youth, Prime Minister Mossadegh had grown to be the leader of the National Front, a political party that advocated for democratization, supported secular liberalism, and advocated for social-democratic economic principles. Targeted strikes by Tudeh Party–supported unions pushed the prime minister to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil company, aiming to take oil profits out of the hands of British imperialists and put that money in the pockets of Iranian workers. With the Shah’s loyalists opposing Mossadegh on one side and Tudeh opposing him on the other, even as he nationalized the oil industry in a conciliation to Tudeh, he faced staunch opposition from the left. Furthermore, Winston Churchill persuaded President Truman that Prime Minister Mossadegh was susceptible to communist influence and had to go. The British MI6 and the American CIA then collaborated on orchestrating a coup to remove him, known as Operation Boot to the British secret service and Operation Ajax to the Americans. A grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt, Kermit Roosevelt Jr., became well known for his participation in ending the Iranian experiment with democracy, as he funneled funds into the supporters of the Shah and paid off participants in the 1953 coup d’état that removed the prime minister from power, all to ensure the steady flow of Iranian oil to Britain and the United States.

Flow the oil did. Production skyrocketed from under a million barrels per day in the 1950s to more than 6 million barrels per day in the 1970s. Of course, as Tudeh would have predicted, the oil boom produced an ever-widening wealth gap in Iran. Furthermore, although the secular nature of Prime Minister Mossadegh’s government had already encouraged enormous advances in women’s rights and the broadening of access to university-level education, critics of the Shah from the right-wing conservative position of Iran’s Muslim clerics argued that the continuation of these trends would mean that the Shah was “westernizing” Iran. In other words, he was supporting a form of cultural imperialism. Furthermore, many new consumer goods and services were only truly available to Iranian elites, resulting in criticism from what remained of the Iranian left after a brutal crackdown orchestrated by the Shah, with the probable collaboration of MI6 and the CIA, in the 1950s destroyed what remained of the Tudeh Party. His 1963 launch of the reformist and modernist-minded “White Revolution” further irritated the religious right in Iran, especially as women were allowed to vote on the referendum to support or not support the reforms of the “White Revolution.” Also, in 1963 and 1964, there were widespread protests against the Shah. His security forces cracked down on the protesters, killing 200, including with police dropping students to their deaths off of the top of high-rise buildings.

The authoritarianism and opulence of the Shah made him increasingly unpopular from the 1960s through the 1970s. His 1967 coronation as Shahanshah, “King of Kings” or “Emperor,” using the ancient title of the Persian emperors, was widely criticized. In 1971, while international jet-setting business executives attended the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great (6th century BCE), the Iranian public was excluded. From 1973 onward, the Shah aimed to transform Iran into the “Great Civilization” (tamaddon-e-bozorg) that would transform the entire world, including “the West”—by which he meant northwestern Europe and the United States.

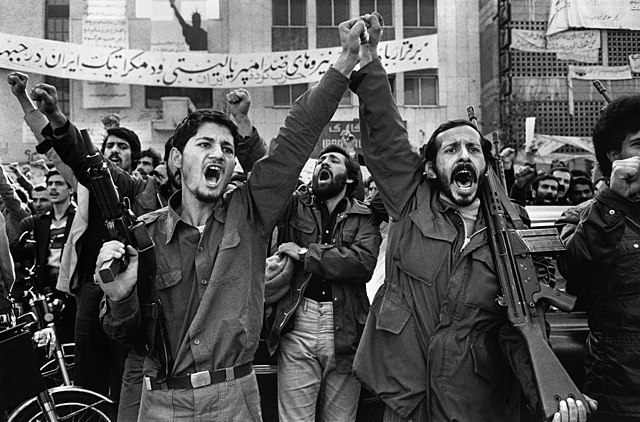

By 1977, anti-Shah protests became even more widespread. The Iranian secret police, SAVAK, had routinely conducted crackdowns, torture sessions, and assassinations in support of the Shah’s control since the 1950s. But by the late 1970s, their brutality was more widespread, as the agency executed killed at least 350 anti-Shah guerrillas and executed up to 100 political prisoners, including, most probably, the son of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Mostafa, although officially, the 1977 death was ruled a “heart attack.” Protests against the Shah continued during the spring and summer of 1978, as the Shah responded by declaring martial law on September 7, one day prior to a massive gathering that had been organized for Jaleh Square in Tehran. As most of the protesters were not aware of the declaration of martial law, thousands upon thousands gathered. They were then surrounded by the military, which fired indiscriminately on the crowd in an event that came to be known as “Black Friday” (Jom’e-ye Siyah) in Iran. Officially, the Shah’s forces maintained that only 64 had died in Jaleh Square, although anti-Shah protesters claimed thousands had died, with many more injured. Other evidence suggests 64 protesters were killed on site in the square itself, while 30 security forces members died in clashes with protesters, and at least 24 people, including a woman and child, were killed by security forces elsewhere in Tehran that day. French historian of ideas and literary critic Michel Foucault traveled to Tehran as a journalist just days after the massacre and reported thousands had died.